Abstract

S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferases regulate a wide range of biological processes through the modification of proteins, nucleic acids, polysaccharides, as well as various metabolites. TYW3/Taw3 is a SAM-dependent methyltransferase responsible for the formation of a tRNA modification known as wybutosine and its derivatives that are required for accurate decoding in protein synthesis. Here, we report the crystal structure of Taw3, a homolog of TYW3 from Sulfolobus solfataricus, which revealed a novel α/β fold. The sequence motif (S/T)xSSCxGR and invariant aspartate and histidine, conserved in TYW3/Taw3, cluster to form the catalytic center. These structural and sequence features indicate that TYW3/Taw3 proteins constitute a distinct class of SAM-dependent methyltransferases. Using site-directed mutagenesis along with in vivo complementation assays combined with mass spectrometry as well as ligand docking and cofactor binding assays, we have identified the active site of TYW3 and residues essential for cofactor binding and methyltransferase activity.

Keywords: wybutosine, tRNA, methyltransferase, TYW3, structural biology

INTRODUCTION

Methyl transfer reactions are ubiquitous in biology. They contribute to the biosynthesis of numerous essential cellular metabolites and clinically relevant small molecules and regulate other processes through the modification of biological macromolecules including DNA, RNA, proteins, polysaccharides, and lipids (Markham 2010). The majority of methyltransferases use S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) as a methyl donor (Kozbial and Mushegian 2005). SAM-dependent methyltransferases can be divided into eight classes, based on their unique sequence and structural features (Schubert et al. 2003; Kozbial and Mushegian 2005; Kaminska et al. 2010; Kimura et al. 2014). The largest classes contain a Rossman fold (class I) or a SET domain (class V) (Kozbial and Mushegian 2005).

Post-transcriptional modifications are unique structural features of RNA molecules. To date, more than 100 types of modified nucleosides including methylation of bases and riboses have been found in various RNA molecules from all domains of life (Machnicka et al. 2013). About 80% of them are found in tRNAs. A wide variety of chemical modifications are found in anticodon regions of tRNAs and play critical roles in proper recognition of codons on the ribosome during protein synthesis. Aberrant tRNA modifications are associated with human diseases such as mitochondrial diseases and cancer (Kirino and Suzuki 2005; Kirino et al. 2005; Pathak et al. 2005; Guy et al. 2015; Shaheen et al. 2015), indicating that RNA modifications ensure proper functions of RNA molecules to maintain higher-ordered biological processes.

Wyosine (imG) and its derivatives such as wybutosine (yW) are hypermodified guanosines. They are found at position 37, 3′ adjacent to the anticodon of tRNA in eukarya and archaea (Thiebe and Poralla 1973; Altwegg and Kubli 1979; Keith and Dirheimer 1980; Bruce and Uhlenbeck 1982). yW stabilizes codon–anticodon base-pairing and ensures accurate translation of phenylalanine codons (Konevega et al. 2004). Early investigation of tRNAPhe in mouse and rat revealed that many tumors are partially defective in yW synthesis, which leads to the production of immature forms of the base (Mushinski and Marini 1979). Hypomodification of yW in tRNAPhe is known to induce −1 frameshifting (Carlson et al. 1999), and influence cancer pathogenesis and expression of viral proteins from human immunodeficiency viruses (Hatfield et al. 1989).

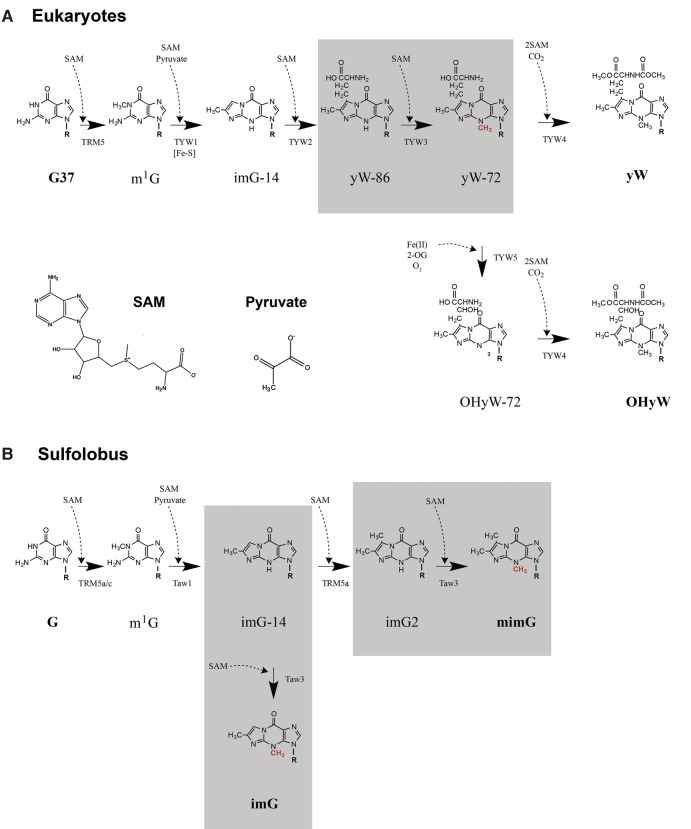

Biogenesis of yW was extensively studied in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. yW is synthesized via multistep enzymatic reactions mediated by five enzymes, TRM5, TYW1, TYW2, TYW3, and TYW4 (Fig. 1A; Noma et al. 2006; Kimura and Suzuki 2015). In the first step, TRM5 methylates G37 of tRNAPhe in the presence of SAM to form 1-methylguanosine (m1G). TYW1, a SAM enzyme containing a radical center, which coordinates an iron–sulfur cluster, catalyzes ring formation of the tricyclic purine base on tRNA by condensation of m1G with two carbons of pyruvate to form imG-14. Then, TYW2 transfers an α-amino-α-carboxypropyl group from SAM to imG-14 forming 7-aminocarboxypropyl-demethylwyosine (yW-86). TYW3 methylates the N4 position of yW-86 in the presence of SAM to form yW-72. Finally, TYW4 catalyzes both methylation and methoxycarbonylation of yW-72 using two SAMs and one bicarbonate to synthesize yW (Suzuki et al. 2009). In mammals and several species of fungi, the β-carbon of the side chain in yW is further hydroxylated to form OHyW. TYW5, a Jumonji C domain-containing protein, catalyzes hydroxylation of yW-72 to form OHyW-72, followed by conversion to OHyW mediated by TYW4 (Noma et al. 2010).

FIGURE 1.

Wybutosine biosynthetic pathway in eukaryotes (A) and wyosine biosynthetic pathway in Sulfolobus species (B). The steps catalyzed by ScTYW3 and the steps proposed to be catalyzed by SsTaw3 are shown within the gray boxes. 2-Oxoglutarate is abbreviated as 2-OG.

In several archaeal species, wyosine (imG) derivatives have been found along with identification of TYW homologs by phylogenetic distribution analysis (McCloskey et al. 2001; Zhou et al. 2004; Noma et al. 2006; de Crecy-Lagard et al. 2010). TYW1-3 homologs called Taw1-3 are widely distributed in euryarchaea, whereas no ortholog of TYW4 is found in all archaea, suggesting that yW-86 and yW-72 are final products in tRNAs from several archaeal species (de Crecy-Lagard et al. 2010). In crenarchaea including Sulfolobus species, Taw1 and Taw3 are present, whereas no Taw2 is found, indicating that imG2 and mimG are the major wyosine derivatives (Fig. 1B).

Structural studies of tRNA-modifying enzymes in this pathway have significantly deepened our mechanistic understanding of yW formation (Bjork et al. 2001; Suzuki et al. 2007, 2009; Umitsu et al. 2009). The crystal structures have been published for TRM5, TYW1, TYW2, TYW4, and TYW5 (Goto-Ito et al. 2007; Suzuki et al. 2007, 2009; Umitsu et al. 2009; Kato et al. 2011), but not for TYW3/Taw3. Here we used X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of the Taw3 methyltransferase from Sulfolobus solfataricus (SsTaw3) at 2.8 Å resolution. The structure revealed a novel α/β fold, which constitutes a new class of methyltransferases composed of three domains: a SHS2 fold domain (Anantharaman and Aravind 2004), a RAGNYA fold domain (Balaji and Aravind 2007), and an N-terminal extension. Since our structure was deposited, structural genomics groups have deposited three structural homologs (PDB IDs: Archaeoglobus fulgidus [PDB 2QG3], Pyrococcus horikoshii [PDB 2DRV, 2IT3, and 2IT2], and Aeropyrum pernix [PDB 2DVK]). However, none of these have been published. In addition to structural characterization, we used in vivo complementation assays combined with mass spectrometry to identify essential residues in TYW3 for the methyltransferase activity. Moreover, we used molecular docking and in vitro binding assays to identify the location of the conserved SAM binding cleft and identify the tRNA binding surface through structural comparison. This represents the first detailed characterization of the TYW3/Taw3 class of SAM-dependent methyltransferases.

RESULTS

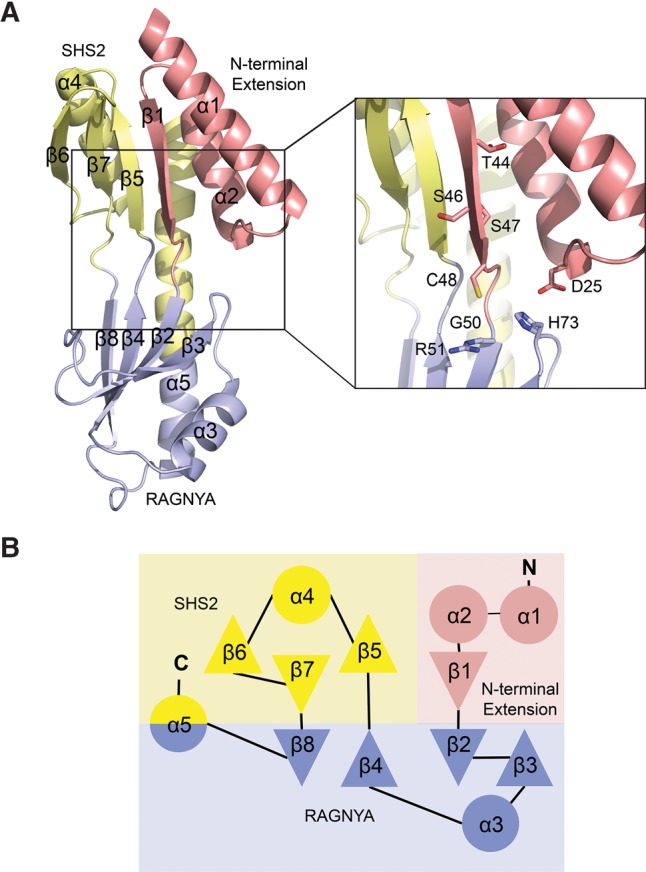

Overall structure

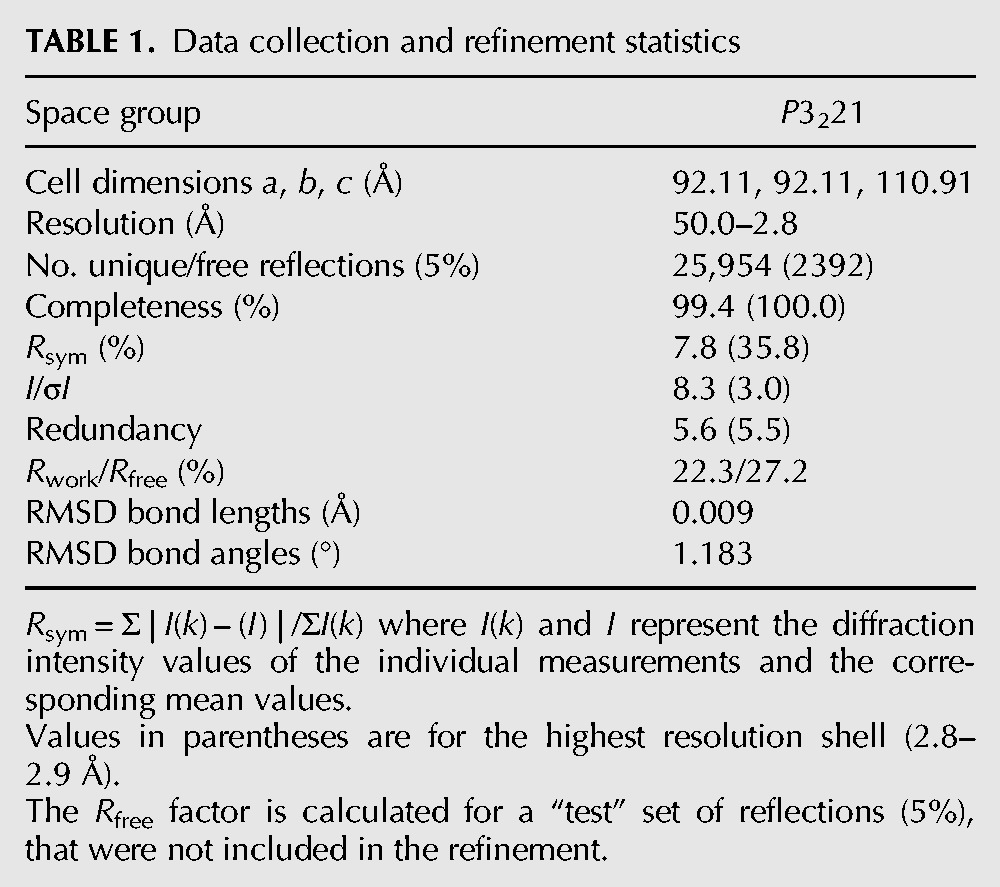

We solved the X-ray crystal structure of SsTaw3, a homolog of yeast TYW3 methyltransferase, to a resolution of 2.8 Å using the MAD method (Fig. 2A). The summary of the data collection and refinement statistics is shown in Table 1. The final structure contains 188 residues (4–192 of the expected 213 residues), three sulfates, and 104 water molecules. The first three N-terminal residues and C-terminal residues 192–213 are completely disordered. There are two copies of SsTaw3 in the asymmetric unit.

FIGURE 2.

Structure of SsTaw3. (A) Crystal structure of SsTaw3, left, and zoom-in view of the crystal structure with conserved residues shown as sticks, left inset. The N-terminal extension, RAGNYA fold, and SHS2 fold domains are colored red, blue, and yellow, respectively. (B) Topology diagram of SsTaw3 with domains colored as in A.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

The crystal structure of SsTaw3 revealed a novel fold, which does not belong to any other class of SAM-dependent methyltransferases. Thus, Taw3 represents the founding member of the ninth class of SAM-dependent methyltransferases. It contains a mixture of α-helix and β-sheet (Fig. 2A). Two four-stranded antiparallel β-sheets line the inside of the concave front facing surface with five α-helices forming the back of the molecule (Fig. 2B). Strands 2, 3, 4, and 8 along with helices 3 and 5 comprise a RAGNYA fold domain (Balaji and Aravind 2007). The RAGNYA fold is an α/β fold composed of four strands and two helices packed against one face, which mediates critical interactions between proteins and a diverse set of ligands including nucleic acids, nucleotides, and other proteins (Balaji and Aravind 2007). Strands 5, 6, and 7 and helix 4 form an SHS2 fold domain, which is a simple modular domain that is named after its strand–helix–strand–strand (SHS2) configuration and is involved in a variety of functions ranging from protein–protein interactions to small-molecule recognition and catalysis (Anantharaman and Aravind 2004). The remaining helices 1 and 2 and sheet 1 constitute an N-terminal extension that is conserved in Taw3 proteins.

Although structural alignment did not return any published structures, the Dali server (Holm and Park 2000) did identify three structural homologs that had been deposited by structural genomics groups after our structure was deposited in the PDB database: (i) hypothetical protein APE0816 from Aeropyrum pernix (Z-score = 19.7; RMSD = 1.56 Å; PDB ID 2DVK), (ii) PH1069 from Pyrococcus horikioshii (Z-score = 21.4; RMSD = 2.01 Å; PDB ID 2IT2), and (iii) AF2059 from Archaeoglobus fulgidus (Z-score = 22.0; RMSD = 2.66 Å; PDB ID 2QG3). All three share the same domain architecture and overall fold as SsTaw3 (Supplemental Fig. S1).

Analysis of enzymatic activity of purified SsTaw3

It has been shown that yeast TYW3 can transfer a methyl group from SAM to yW-86 on tRNAPhe to generate yW-72 in vitro as well as in vivo (Noma et al. 2006). According to the phylogenetic analysis (de Crecy-Lagard et al. 2010), Taw3 is predicted to be a tRNA methyltransferase responsible for mimG formation in Sulfolobus species. In fact, mimG was detected in Sulfolobus species (de Crecy-Lagard et al. 2010). However, there is no report regarding which tRNA has mimG in Sulfolobus species. To examine enzymatic activity of Taw3 in vitro, we needed to prepare hypomodified tRNA bearing imG2, which is a possible precursor for mimG. However, no genetic approach to disrupt the taw3 gene in Sulfolobus solfataricus or other related species is available. Alternatively, we examined whether SsTaw3 could catalyze the same reaction as its eukaryotic homolog TYW3. For this experiment, we prepared crude tRNA from the yeast ΔTYW3 deletion strain that accumulates yW-86 as a substrate for the in vitro assay. Recombinant SsTaw3 and yeast TYW3 (ScTYW3), as a positive control, were incubated with the crude tRNA in the presence of SAM, followed by digestion to nucleosides and subjected to LC-mass spectrometric analysis. In our control experiment, ScTYW3 converted yW-86 to yW-72 (Supplemental Fig. S2), as previously reported (Noma et al. 2006), whereas no conversion took place with SsTaw3 (Supplemental Fig. S3), indicating that yeast tRNAPhe with yW-86 is not an appropriate substrate for SsTaw3. Next, we examined whether imG-14 could be used as a substrate for SsTaw3. To test this hypothesis, we prepared crude tRNA from the yeast ΔTYW2 deletion strain that accumulates imG-14, and incubated it with SsTaw3 in the presence of SAM. No reduction of imG-14 and no increase of imG were detected (Supplemental Fig. S4), showing that yeast tRNAPhe with imG-14 is also not a substrate for SsTaw3.

Sequence analysis

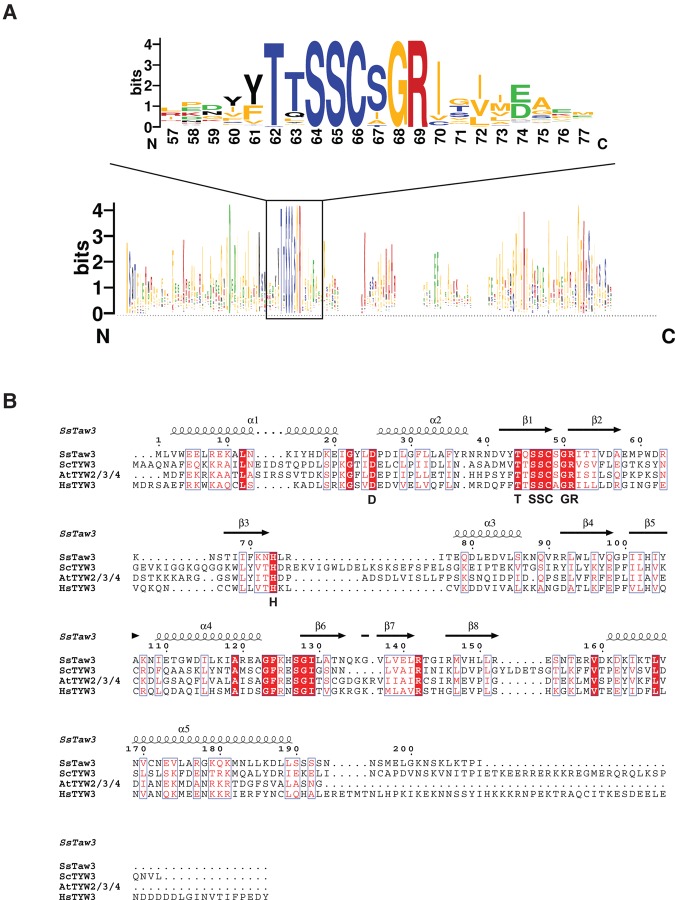

In addition to unique structural characteristics, methyltransferase classes can also be distinguished based on conserved sequence features (Kozbial and Mushegian 2005). The hallmark of SAM-binding Rossman-like fold methyltransferases is a GxGxG consensus sequence, which forms part of the SAM binding site. SAM-radical methyltransferases can be recognized by the hallmark CxxxCxxC motif near their N terminus followed by a GG motif. SET domain methyltransferases can be identified by two signature motifs, ELxF/YDY and NHS/CxxPN. We performed sequence analysis using 150 sequences of TYW3 enzymes. Interestingly, we did not uncover any sequence motifs that are conserved in other classes of methyltransferases. Instead our sequence analysis revealed eight absolutely conserved residues in the TYW3 protein family: an aspartate located on the N-terminal extension, a histidine found at the end of strand 3 in the RAGNYA fold domain, and the motif (S/T)xSSCxGR, which spans the junction between the SHS2 and RAGNYA fold domains (residues Asp25, Ser47, Cys48, Gly50, Arg51, and His73 in SsTaw3) (Fig. 2A, inset; Fig. 3). In addition to the novel fold, these conserved sequence elements are defining characteristics of this class of methyltransferase. The conservation and polar nature of these residues also suggests a critical role for these residues in substrate binding and catalysis. Interestingly, despite being positioned distantly in the primary sequence of the enzyme, these eight residues cluster in all of the crystal structures of the TYW3 family and form the putative active site for TYW3 enzymes (Fig. 2A, inset; Fig. 3). It has been postulated that the single absolutely conserved cysteine forms a covalent intermediate with the methyl group from SAM prior to being transferred to the target nitrogen atom on the yW precursor (Balaji and Aravind 2007), which would represent a novel methyltransferase mechanism. This intermediate would resemble the stable side chain of methionine. Another possibility is that the cysteine might form a covalent intermediate with one of the carbons within the nucleoside rings, which facilitates nucleophilic catalysis. This type of mechanism is utilized by many nucleic acid methyltransferases (Motorin et al. 2010).

FIGURE 3.

Sequence analysis of Taw3/TYW3 methyltransferase. (A) Weblogo generated from the alignment of 150 Taw3/TYW3 sequences. The bottom panel shows the first 200 residues of the alignment and the top panel shows a 20 amino acid stretch centered on the Taw3/TYW3 conserved sequence motif. (B) Structure-based sequence alignment aligned to the secondary structure elements of SsTaw3 and including SsTaw3 (Sulfolobus solfataricus), ScTYW3 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), AtTYW3 (Arabidopsis thaliana), and HsTYW3 (Human) sequences. The signature Taw3/TYW3 sequences are included below the alignment in black.

Site-directed mutagenesis and in vivo complementation studies

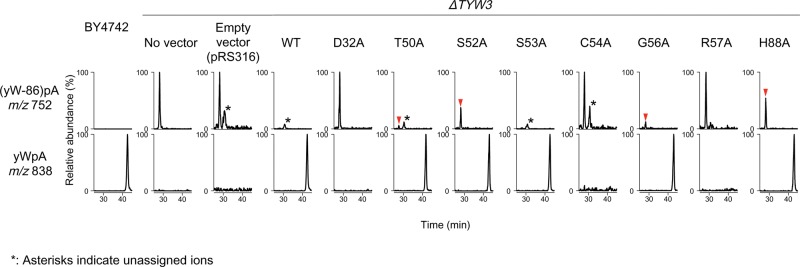

Since we were unable to detect enzymatic activity of SsTaw3 in vitro, we decided to carry out in vivo complementation of the yeast ΔTYW3 deletion strain by a series of plasmid-encoding TYW3 variants to probe the role of the conserved putative active site residues. The ΔTYW3 deletion strain was transformed with a series of plasmids harboring wild-type TYW3 or mutants, D32A, T50A, S52A, S53A, C54A, G56A, R57A, and H88A. Total RNA was extracted from each transformant and subjected to nucleoside analysis by LC-mass spectrometry (Fig. 4). In the ΔTYW3 deletion strain, yW-86 can be detected as a proton adduct of dimer form, (yW-86)pA (m/z 752), as reported previously (Noma et al. 2006). When rescued by WT TYW3, yW-86 is methylated by TYW3 to form yW-72, and then fully modified by TYW4 to form yW, detected as a proton adduct of dimer form, yWpA (m/z 838) (Noma et al. 2006). Of the eight mutations studied, we saw varying degrees of complementation. Two mutants, S53A (S47 in SsTaw3) and G56A (G50 in SsTaw3) fully complemented yW formation (Fig. 4). D32, C54, and R57 (D25, C48, R51 in SsTaw3), on the other hand, are essential for the activity, since TYW3 mutants with the corresponding Ala substitutions did not rescue yW formation at all (Fig. 4). In contrast, T50A, S52A, and H88A (T44, S46, and H73 in SsTaw3) only partially complemented yW formation, as small levels of yW-86 were detected in these transformants (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

In vivo complementation by ScTYW3 mutants. The yeast ΔTYW3 deletion strain was transformed with a series of plasmids containing no insert, WT ScTYW3, or mutant ScTYW3 D32A, T50A, S52A, S53A, C54A, G56A, R57A, or H88A. Total RNA was extracted from each transformant and subjected to nucleoside analysis by LC-mass spectrometry. The relative abundance of (yW-86)pA (m/z 752) and yWpA (m/z 838) are shown for each transformant.

Substrate and cofactor binding sites

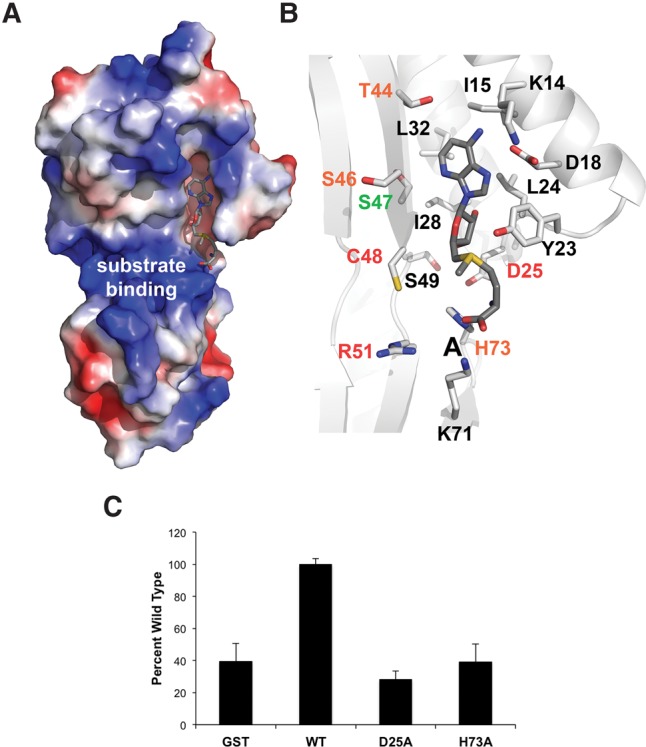

Cocrystallization and soaking with SAM and S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine (SAH) were attempted, but both proved unsuccessful. This may indicate the requirement for additional factors or the substrate to be bound in order to obtain stable association of the enzyme with the cofactor or the crystal packing may exclude the cofactor. Therefore, we performed molecular docking simulations with SAM and our apo-structure to help identify the cofactor binding site. Autodock placed the methyl donor in a small solvent exposed cleft adjacent to the active site (Fig. 5; Morris et al. 2009). The cleft is formed by the N-terminal extension and is conserved in all available Taw3 protein structures (Supplemental Fig. S1). The adenosyl moiety is positioned within the cleft making contact with several poorly conserved amino acids including K14, I15, D18, Y23, L24, I28, and L32. Furthermore, the sulfonium ion and methionine moieties extend beyond the end of the cleft, making contacts with charged residues in the active site (Fig. 5A). The conserved aspartate (D25 in SsTaw3) interacts with the sulfonium ion of SAM and was shown to be essential for TYW3 activity in our yeast complementation assay (Fig. 5B). The carboxyl group on SAM interacts with the invariant histidine (H73 in SsTaw3) in our docking model, which is more amenable to amino acid substitution showing only reduced activity in our complementation assay (Fig. 5B). Interestingly, there is a sulfate ion located in the same position as the carboxyl group of SAM in our docking model in one molecule of the asymmetric unit of our structure, which may mimic the interactions TYW3/Taw3 enzymes make with the carboxyl group of SAM. To test the role of the invariant aspartate and histidine in SAM binding we used a radioactive SAM binding assay. Mutation of either D25 or H73 reduced SsTaw3 SAM binding to the same levels as GST, which serves as a negative control (Fig. 5C), confirming their role in cofactor binding.

FIGURE 5.

Substrate binding. (A) The electrostatic surface view of our SsTaw3 structure is shown with SAM docked. (B) Zoom in of SAM docking to SsTaw3. Side chains within bonding distance of SAM are shown as sticks. Residues labeled in red are required to complement ScTYW3 in our in vivo complementation assay. Residues labeled in orange and green only partially complemented and completely complemented ScTYW3 function in vivo, respectively. Residues labeled in black were not tested. (C) SAM binding activity was analyzed using S-[methyl-14C]adenosyl-L-methionine and recombinant SsTaw3 and GST proteins. Values represent the average and standard deviation of two to three measurements presented as percentage of wild type.

Figure 5A shows the surface charge distribution in the SsTaw3 structure. The solvent exposed surface of the RAGNYA fold contains a large positively charged patch that also features a well-positioned sulfate ion on each molecule in the asymmetric unit. This patch lies directly adjacent to the active site of the enzyme, which makes it likely that this serves as a binding surface for the phosphate backbone of its unidentified RNA substrate. Sulfate ions often mark the position of DNA or RNA backbone phosphates in nucleic acid binding proteins. In Supplemental Figure S1, we include the electrostatic surface potential for the three other Taw3 family members with structures available. Two of the three structures also present a large positively charged patch in the same position adjacent to the catalytic center suggesting that this may be a conserved RNA binding site in Taw3 methyltransferases. Interestingly, nucleic acid binding is among the known functions of the RAGNYA fold. Other RAGNYA fold containing proteins such as the L3-I, Tombusvirus p19, and ribosomal protein L1 interact with double-stranded regions of rRNA or siRNA–mRNA duplexes, the family Y DNA polymerase C-terminal domains and phage NinB proteins interact with DNA, and the RNA/DNA ligases interact with either RNA or DNA (Balaji and Aravind 2007). Despite similar electrostatic potential maps in the existing Taw3 structures, the only conserved residue that is a part of this charged surface is arginine, which sits at the junction of the active site and RNA binding surface. Interestingly, we show that this arginine is required for TYW3 complementation in yeast, which may be due to a role in tRNA binding (Fig. 4). However, since the substrate of SsTaw3 remains unknown we cannot directly test this hypothesis.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we provide the first characterization of the most recently identified class of SAM-dependent methyltransferases, the TYW3 family, which are tRNA-yW N-4 methyltransferases involved in biosynthesis of the hypermodified yW base (Noma et al. 2006). Through primary sequence analysis we show that TYW3 proteins do not contain motifs that are characteristic of the other classes of methyltransferases. Instead, we identify sequence features that are unique to TYW3 proteins including the signature motif (S/T)xSSCxGR, an N-terminal aspartate, and a C-terminal histidine. In addition, we solved the first crystal structure of a TYW3 enzyme, which reveals a novel fold with no homology to any of the known methyltransferase classes. This makes TYW3 methyltransferases the ninth class of SAM-dependent methyltransferase that appear to have independently evolved.

Interestingly, despite being separated in the primary sequence, the hallmark sequence features of TYW3 methyltransferases cluster within our structure. We propose that these residues are involved in substrate binding and/or catalysis. Using the in vivo complementation of yeast ΔTYW3 strain combined with mass spectrometry, we revealed the importance of these conserved sequence features in TYW3 function, which also substantiates the active site identified based on the structure. The aspartate, cysteine, and arginine are required for TYW3 function and mutation of the threonine, the first serine, and histidine impair TYW3 function. Docking simulations place SAM in a surface exposed cleft in contact with both the conserved aspartate and the histidine. Mutation of either of these residues abolishes SAM binding. Therefore, we suggest that the defects in TYW3 function caused by mutating these residues are due to faulty SAM binding. Moreover, we suggest that a large basic patch on the surface of the RAGNYA fold domain may be the site of tRNA binding, which is also supported by the functional defect caused by mutating the only conserved residue on this surface.

We tested SsTaw3 activity on two different substrates yW-86 and imG-14 on tRNAPhe derived from yeast ΔTYW3 and ΔTYW2 strains, respectively. However, neither of these substrates was modified by SsTaw3. Which tRNAs in Sulfolobus contain mimG or imG is unknown; therefore, tRNAPhe might not be a substrate for Taw3 at all. Moreover, even if Taw3 methylates tRNAPhe in Sulfolobus species, yeast tRNAPhe may not be a suitable substrate for Taw3 due to the heterologous combination of enzyme and substrate. Therefore, the substrate of archaeal Taw3 activity remains an interesting and unanswered question. Each of the yeast TYW enzymes is active alone in vitro (Noma et al. 2006). However, it has been suggested that yW biosynthesis may be facilitated by the formation of a multienzymatic complex of TYW proteins (Noma et al. 2006). This is supported by the fact that the plant orthologs of TYW2, TYW3, and a part of TYW4 are present as a single large fusion protein. SsTaw3 might require other factors that we did not include in our in vitro assays to be active. Ultimately, this highlights interesting questions that still remain to be answered about the different roles of wyosine derivatives and their biosynthesis in both archaea and eukaryotes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, expression, and protein purification

The open reading frame of the SSO0622 gene from Sulfolobus solfataricus was PCR amplified and inserted between the NdeI and BamHI restriction sites of a modified pET-15b expression vector (Novagen) (p11) as previously described (Zhang et al. 2001). This construct generated an N-terminal hexahistidine tag joined to the SsTaw3 protein by the TEV protease recognition site (ENLYFQ↓G). Recombinant native SsTaw3 was expressed in BL21(DE3) cells. Cells were cultivated at 37°C in 1 L of Luria Bertani broth medium containing 100 µg/mL ampicillin until the OD600 nm reached 0.6. Isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside was added to the medium to a final concentration of 1 mM to induce expression and the cells were cultured for an additional 4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in Buffer A (20 mM imidazole, 0.3 M NaCl, and 20 mM NaH2PO4, pH 8.0), and disrupted by sonication. The crude extract was heated at 70°C for 30 min, and the denatured protein was then removed by centrifugation (3220g for 15 min). The supernatant solution was loaded on a High Performance Ni2+-Sepharose column (HisTrapTM HP, 5 mL) equilibrated with Buffer A. Protein was eluted with Buffer A supplemented with 0.4 M imidazole or cleaved on a column using TEV protease (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's protocol and eluted with Buffer A. The protein containing fractions were pooled and loaded on a Sephacryl S-200 high-resolution column (Amersham Biosciences Co.) that was pre-equilibrated with Buffer B (10 mM HEPES Na, pH 7.5) with 0.5 M NaCl. The protein containing fractions were pooled, concentrated, and used as the purified enzyme preparation. Seleno-methionine derivative of SsTaw3 was expressed in DL41 (DE3) cells (Novagen) in minimal medium supplemented with seleno-methionine and purified under the same conditions as the native protein.

Protein crystallization

Protein crystals of SsTaw3 were generated through hanging drop vapor diffusion at 21°C by mixing 2 µL of protein solution (35 mg/mL) with 2 µL of well solution consisting of 23% MME 5K, 0.2 M ammonium sulfate, and 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 4.6.

X-ray diffraction, structure determination, refinement, and modeling

SsTaw3 crystals were placed in a cryoprotectant composed of 23% sucrose added to the crystallization solution and then flash frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to data collection. Multiwavelength anomalous dispersion data were collected at three wavelengths 0.97927, 0.97948, and 0.96404 Å at the Advanced Photon Source (APS, Argonne, IL) beamline 19-ID of the Structural Biology Center-CAT with a SBC-3 CCD detector. The data were processed using HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor 1997). Data collection and processing statistics are shown in Table 1.

The structure of SsTaw3 was solved using the multiwavelength anomalous dispersion (MAD) method. Selenium sites were located using SOLVE (Terwilliger and Berendzen 1999; Terwilliger 2000). Selenium position refinement, phase calculation, and density modification was performed by SHARP (de La Fortelle and Bricogne 1997). The structural model was built and refined by XFIT, CNS, and Refmac (Brunger et al. 1998; McRee 1999). The final refinement statistics can be found in Table 1 and the coordinates have been deposited in the PDB (the accession code 1TLJ). SAM docking experiments were performed with AutoDock (Morris et al. 2009).

SsTaw3 activity measurements

Yeast strains were cultured and bulk tRNA was extracted as previously described (Noma et al. 2006; de Crecy-Lagard et al. 2010). ScTYW3 was prepared as before (Noma et al. 2006). In vitro reactions were carried out in a total of 25 µL containing 100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 1 mM spermidine, 5% glycerol, with or without 10 µg of protein, with or without 2 mM SAM, with 40 µg of yeast derived tRNAs. Reactions were incubated at 60°C for 2 h. The RNA was then precipitated, digested, and subjected to LC mass spectrometry as previously described (Noma et al. 2006; de Crecy-Lagard et al. 2010).

In vivo complementation assay

In vivo complementation was carried out essentially as previously described (Suzuki et al. 2007). The wild-type (BY4742) and ΔTYW3 yeast strains were obtained from EUROSCARF. The ΔTYW3 strain was transformed with empty plasmid (pRS316), pScTYW3 bearing a TYW3 gene with its flanking region including its natural promotor (WT), or pScTYW3 mutant containing one of the following mutations: D32A, T50A, S52A, S53A, C54A, G56A, R57A, and H88A. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out on the pScTYW3 plasmid using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene). Total RNA was extracted from each transformant cultured in YPD or SC-ura medium up to A600 = 1.5–2.0, and 40 µg of which was subjected to nucleoside analysis by LC-mass spectrometry as previously described (Noma et al. 2006).

S-adenosylmethionine binding assay

Recombinant proteins (10 µM) and 100 µM S-[methyl-14C]adenosyl-L-methionine (58 mCi/mmol) (PerkinElmer) were incubated in a total volume of 50 µL of binding buffer (50 mM KH2PO4, pH 8.0, adjusted with KOH) for 10 min at 30°C. The mixture was passed over a HAWP02500 filter (Millipore). The filter was washed four times with 300 µL of the binding buffer, and the bound S-[methyl-14C]adenosyl-l-methionine was quantified by liquid scintillation counting using a LS 6500 multipurpose scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter).

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Natalie Roy in the Jia laboratory for technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant (MOP-48370) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to Z.J. G.B. and A.F.Y. were supported by Genome Canada (through the Ontario Genomics Institute, 2009-OGI-ABC-1405) and the Ontario Research Fund (ORF-GL2-01-004), as well as by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Strategic Network Grant IBN. Z.J. holds a Canada Research Chair in Structural Biology. T.S. and T.O. are supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author contributions: M.A.C., G.B., A.W., T.O., K.S., T.S., A.F.Y., and Z.J. designed the experiments. M.A.C., G.B., A.W., T.O., and K.S. conducted the experiments. M.A.C. and G.B. crystallized and collected X-ray data sets. A.W. determined the crystal structure. M.A.C. performed sequence analysis and cofactor docking. T.O. and K.S. performed activity measurements and in vivo complementation assays. M.A.C. analyzed data and prepared the manuscript. M.A.C., G.B., T.O., K.S., T.S., A.F.Y., and Z.J. edited the manuscript.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.rnajournal.org/cgi/doi/10.1261/rna.057943.116.

REFERENCES

- Altwegg M, Kubli E. 1979. The nucleotide sequence of phenylalanine tRNA2 of Drosophila melanogaster: four isoacceptors with one basic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 7: 93–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantharaman V, Aravind L. 2004. The SHS2 module is a common structural theme in functionally diverse protein groups, like Rpb7p, FtsA, GyrI, and MTH1598/TM1083 superfamilies. Proteins 56: 795–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji S, Aravind L. 2007. The RAGNYA fold: a novel fold with multiple topological variants found in functionally diverse nucleic acid, nucleotide and peptide-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 35: 5658–5671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork GR, Jacobsson K, Nilsson K, Johansson MJ, Bystrom AS, Persson OP. 2001. A primordial tRNA modification required for the evolution of life? EMBO J 20: 231–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce AG, Uhlenbeck OC. 1982. Enzymatic replacement of the anticodon of yeast phenylalanine transfer ribonucleic acid. Biochemistry 21: 855–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 54: 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BA, Kwon SY, Chamorro M, Oroszlan S, Hatfield DL, Lee BJ. 1999. Transfer RNA modification status influences retroviral ribosomal frameshifting. Virology 255: 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Crecy-Lagard V, Brochier-Armanet C, Urbonavicius J, Fernandez B, Phillips G, Lyons B, Noma A, Alvarez S, Droogmans L, Armengaud J, et al. 2010. Biosynthesis of wyosine derivatives in tRNA: an ancient and highly diverse pathway in Archaea. Mol Biol Evol 27: 2062–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de La Fortelle E, Bricogne G. 1997. Maximum-likelihood heavy-atom parameter refinement for multiple isomorphous replacement and multiwavelength anomalous diffraction methods. Methods Enzymol 276: 472–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto-Ito S, Ishii R, Ito T, Shibata R, Fusatomi E, Sekine SI, Bessho Y, Yokoyama S. 2007. Structure of an archaeal TYW1, the enzyme catalyzing the second step of wye-base biosynthesis. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 63: 1059–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy MP, Shaw M, Weiner CL, Hobson L, Stark Z, Rose K, Kalscheuer VM, Gecz J, Phizicky EM. 2015. Defects in tRNA anticodon loop 2′-O-methylation are implicated in nonsyndromic X-linked intellectual disability due to mutations in FTSJ1. Hum Mutat 36: 1176–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield D, Feng YX, Lee BJ, Rein A, Levin JG, Oroszlan S. 1989. Chromatographic analysis of the aminoacyl-tRNAs which are required for translation of codons at and around the ribosomal frameshift sites of HIV, HTLV-1, and BLV. Virology 173: 736–742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L, Park J. 2000. DaliLite workbench for protein structure comparison. Bioinformatics 16: 566–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaminska KH, Purta E, Hansen LH, Bujnicki JM, Vester B, Long KS. 2010. Insights into the structure, function and evolution of the radical-SAM 23S rRNA methyltransferase Cfr that confers antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 1652–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M, Araiso Y, Noma A, Nagao A, Suzuki T, Ishitani R, Nureki O. 2011. Crystal structure of a novel JmjC-domain-containing protein, TYW5, involved in tRNA modification. Nucleic Acids Res 39: 1576–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith G, Dirheimer G. 1980. Primary structure of Bombyx mori posterior silkgland tRNAPhe. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 92: 109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Suzuki T. 2015. Iron-sulfur proteins responsible for RNA modifications. Biochim Biophys Acta 1853: 1272–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura S, Miyauchi K, Ikeuchi Y, Thiaville PC, Crecy-Lagard V, Suzuki T. 2014. Discovery of the β-barrel-type RNA methyltransferase responsible for N6-methylation of N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine in tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 42: 9350–9365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino Y, Suzuki T. 2005. Human mitochondrial diseases associated with tRNA wobble modification deficiency. RNA Biol 2: 41–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino Y, Goto Y, Campos Y, Arenas J, Suzuki T. 2005. Specific correlation between the wobble modification deficiency in mutant tRNAs and the clinical features of a human mitochondrial disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 7127–7132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konevega AL, Soboleva NG, Makhno VI, Semenkov YP, Wintermeyer W, Rodnina MV, Katunin VI. 2004. Purine bases at position 37 of tRNA stabilize codon-anticodon interaction in the ribosomal A site by stacking and Mg2+-dependent interactions. RNA 10: 90–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozbial PZ, Mushegian AR. 2005. Natural history of S-adenosylmethionine-binding proteins. BMC Struct Biol 5: 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machnicka MA, Milanowska K, Osman Oglou O, Purta E, Kurkowska M, Olchowik A, Januszewski W, Kalinowski S, Dunin-Horkawicz S, Rother KM, et al. 2013. MODOMICS: a database of RNA modification pathways—2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res 41: D262–D267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham GD. 2010. Encyclopedia of life sciences. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey JA, Graham DE, Zhou S, Crain PF, Ibba M, Konisky J, Soll D, Olsen GJ. 2001. Post-transcriptional modification in archaeal tRNAs: identities and phylogenetic relations of nucleotides from mesophilic and hyperthermophilic Methanococcales. Nucleic Acids Res 29: 4699–4706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRee DE. 1999. XtalView/Xfit—a versatile program for manipulating atomic coordinates and electron density. J Struct Biol 125: 156–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. 2009. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem 30: 2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motorin Y, Lyko F, Helm M. 2010. 5-methylcytosine in RNA: detection, enzymatic formation and biological functions. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 1415–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushinski JF, Marini M. 1979. Tumor-associated phenylalanyl transfer RNA found in a wide spectrum of rat and mouse tumors but absent in normal adult, fetal, and regenerating tissues. Cancer Res 39: 1253–1258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma A, Kirino Y, Ikeuchi Y, Suzuki T. 2006. Biosynthesis of wybutosine, a hyper-modified nucleoside in eukaryotic phenylalanine tRNA. EMBO J 25: 2142–2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma A, Ishitani R, Kato M, Nagao A, Nureki O, Suzuki T. 2010. Expanding role of the jumonji C domain as an RNA hydroxylase. J Biol Chem 285: 34503–34507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276: 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak C, Jaiswal YK, Vinayak M. 2005. Hypomodification of transfer RNA in cancer with respect to queuosine. RNA Biol 2: 143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert HL, Blumenthal RM, Cheng X. 2003. Many paths to methyltransfer: a chronicle of convergence. Trends Biochem Sci 28: 329–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen R, Abdel-Salam GM, Guy MP, Alomar R, Abdel-Hamid MS, Afifi HH, Ismail SI, Emam BA, Phizicky EM, Alkuraya FS. 2015. Mutation in WDR4 impairs tRNA m7G46 methylation and causes a distinct form of microcephalic primordial dwarfism. Genome Biol 16: 210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Noma A, Suzuki T, Senda M, Senda T, Ishitani R, Nureki O. 2007. Crystal structure of the radical SAM enzyme catalyzing tricyclic modified base formation in tRNA. J Mol Biol 372: 1204–1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Noma A, Suzuki T, Ishitani R, Nureki O. 2009. Structural basis of tRNA modification with CO2 fixation and methylation by wybutosine synthesizing enzyme TYW4. Nucleic Acids Res 37: 2910–2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC. 2000. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 56: 965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. 1999. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 55: 849–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiebe R, Poralla K. 1973. Origin of the nucleoside Y in yeast tRNAPhe. FEBS Lett 38: 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umitsu M, Nishimasu H, Noma A, Suzuki T, Ishitani R, Nureki O. 2009. Structural basis of AdoMet-dependent aminocarboxypropyl transfer reaction catalyzed by tRNA-wybutosine synthesizing enzyme, TYW2. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 15616–15621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RG, Skarina T, Katz JE, Beasley S, Khachatryan A, Vyas S, Arrowsmith CH, Clarke S, Edwards A, Joachimiak A, et al. 2001. Structure of Thermotoga maritima stationary phase survival protein SurE: a novel acid phosphatase. Structure 9: 1095–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Sitaramaiah D, Noon KR, Guymon R, Hashizume T, McCloskey JA. 2004. Structures of two new “minimalist” modified nucleosides from archaeal tRNA. Bioorg Chem 32: 82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.