Abstract

Background

The prevalence of cutaneous adverse food reactions (CAFRs) in dogs and cats is not precisely known. This imprecision is likely due to the various populations that had been studied. Our objectives were to systematically review the literature to determine the prevalence of CAFRs among dogs and cats with pruritus and skin diseases.

Results

We searched two databases for pertinent references on August 18, 2016. Among 490 and 220 articles respectively found in the Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded) and CAB Abstract databases, we selected 22 and nine articles that reported data usable for CAFR prevalence determination in dogs and cats, respectively. The prevalence of CAFR in dogs and cats was found to vary depending upon the type of diagnoses made. Among dogs presented to their veterinarian for any diagnosis, the prevalence was 1 to 2% and among those with skin diseases, it ranged between 0 and 24%. The range of CAFR prevalence was similar in dogs with pruritus (9 to 40%), those with any type of allergic skin disease (8 to 62%) and in dogs diagnosed with atopic dermatitis (9 to 50%). In cats presented to a university hospital, the prevalence of CAFR was less than 1% (0.2%), while it was fairly homogeneous in cats with skin diseases (range: 3 to 6%), but higher in cats with pruritus (12 to 21%) than in cats with allergic skin disease (5 to 13%).

Conclusions

Among dogs and cats with pruritus and those suspected of allergic skin disease, the prevalence of CAFR is high enough to justify this syndrome to be ruled-out with a restriction (elimination)-provocation dietary trial. This must especially be considered in companion animals with nonseasonal pruritus or signs of allergic dermatitis.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12917-017-0973-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Allergy, Atopic Dermatitis, Canine, Cat, Dog, Feline, Food Allergy, Itch, Pruritus

Background

There is variability about the reported prevalence of cutaneous adverse food reactions (CAFRs) in dogs and cats. This heterogeneity of data might be caused by a combination of differences in the geographical populations studied, variability in animal groups in which the prevalence is reported and, perhaps, in the method of diagnosis of CAFR itself.

Clinical scenario

You have two patients: a 1-year-old male intact West Highland white terrier and a 3-year-old female spayed Siamese cat. Both animals exhibit pruritus that manifests by year-round scratching. The dog also suffers from occasional episodes of urticaria, as well as bouts of soft mucus-containing stools. The cat has several patches of self-induced hair loss on the abdomen and medial thighs. You inform the owners of both patients that you suspect that all clinical signs might be caused by a reaction to their pet’s diet. The owners ask you how frequent this type of problem is.

Structured question

What is the prevalence of CAFR among dogs and cats with pruritus or skin diseases?

Search strategy

We searched the Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded) and CAB Abstract databases on August 18, 2016 using the following string: ((dog or dogs or canine) or (cat or cats or feline)) and (food or diet*) and (atop* or allerg* or reaction*) and (prurit* or cutan* or skin) not (human* or adult* or child*). We limited the search to journal articles published from 1980 to present; there were no language restrictions.

Identified evidence

Our literature search identified 490 and 220 articles in the CAB Abstract and Web of Science databases, respectively. Citations were initially assessed for the identification of articles reporting original information; review papers were not considered further. Abstracts were then screened and potentially relevant papers were read in full. The bibliography of these articles was examined further for additional pertinent citations.

Altogether, we selected 28 papers that provided usable information [1–28]. Twenty-seven articles were identified from the search of the CAB abstract database, while 18 of these 27 papers (67%) were also found in the Web of Science archives; none was uniquely detected in the Web of Science query, while one additional publication was identified from scanning the references of selected articles [14]. There were nine studies reporting information on the prevalence of CAFR in cats [1, 3, 5, 10, 22, 24–27] and 22 on that in dogs [1–4, 6–21, 23, 28]; three reported data usable for both dogs and cats [1, 3, 10]. Studies were reported from 1990 [1] to 2015 [28]. All papers were in English except for one each in French [3], Dutch [4], German [9], Italian [13] and Portuguese [18].

Evaluation of evidence

The selected articles reported information from small animal patients from all over the world: cats came from Australia [26, 27], Canada [1, 3], New Zealand [5], the UK [10], the USA [24, 25] or from a worldwide survey [22]. Dogs with CAFR had been diagnosed in Brazil [18, 19, 28], Canada [1, 3], the Czech Republic [16], Hungary [14], Iran [23], Italy [13, 20], the Netherlands and Belgium [4, 7], Slovenia [15], Switzerland [9, 17], Sweden [12], the UK [6, 8, 10, 11] and the USA [2]; there was also a large worldwide survey [21]. Only two articles contained reviews of diagnoses made in general veterinary practices [10, 12], while all other reports were from patients seen at university or private specialty clinics.

The method of diagnosis of CAFR was not specified in three surveys [1, 10, 18], while, in all other reports, the diagnosis was made after observing a reduction of pruritus manifestations after feeding an elimination diet lasting most often between 6 and 8 weeks. In all but four studies [3, 12, 14, 28], this elimination diet was followed by a challenge with offending allergens. Importantly, in only four articles was an elimination diet performed in the entire population of study patients.

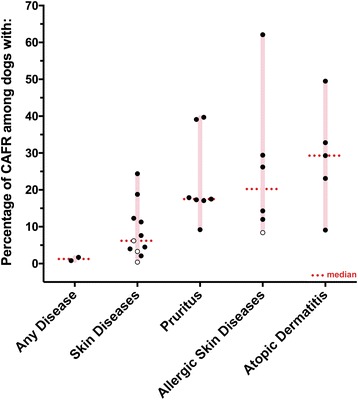

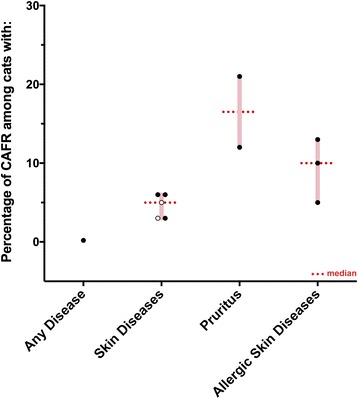

The prevalence of CAFRs in dogs and cats was found to vary depending upon the type of diagnosis made. In dogs (Fig. 1), the prevalence of CAFRs was low among dogs presented to their veterinarian for any diagnosis (1 to 2%) or among those with skin diseases (median: 6%; range: 0 to 24%). Furthermore, ranges of reported prevalence of CAFR overlapped between dogs with pruritus (median: 18%; range: 9 to 40%), those with any type of allergic skin disease (median: 20%; range: 8 to 62%) and dogs with skin lesions suggestive of atopic dermatitis (median: 29%; range: 9 to 50%) (Fig. 1; Additional file 1). A similar pattern was found in feline patients (Fig. 2). In cats presented to a university hospital [24], the prevalence of CAFR was reported to be very low (0.2%), while it was fairly homogeneous in cats with skin diseases (median: 5%; range: 3 to 6%); it was higher in cats with pruritus (12 and 21%) than in cats with allergic skin disease (median: 10%; range: 5 to 13%) (Fig. 2; Additional file 2). We attribute the latter observation to cats occasionally manifesting a CAFR as pruritus without visible dermatitis. Altogether, there were not enough data to compare the prevalence of CAFR in dogs and cats from different geographical locations.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of CAFRs among dogs with various conditions. Open circles correspond to the three studies in which the method of diagnosis of CAFR was not specified [1, 10, 18]

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of CAFRs among cats with various conditions. Open circles correspond to the two studies in which the method of diagnosis of CAFR was not specified [1, 10, 18]

As in most summaries incorporating results from studies performed at different times and institutions, the main limitation of this review is the likely variability of methods or criteria used to make the diagnosis of CAFR. A similar inconsistency probably also existed in the way atopic dermatitis was diagnosed between studies. Whenever details were provided, however, CAFRs and AD were diagnosed according to accepted standards at the time of publication. Importantly, in all but four studies [7, 8, 11, 17], not all animals from the reported population (e.g. dogs with any or skin diseases) had been subjected to an elimination diet. This lack of systematic dietary testing likely led to a lower prevalence of CAFR reported in articles where the diet change was not made in all pets.

Conclusion and implication for practitioners

Our review of the existing evidence suggests that the prevalence of CAFRs in dogs and cats varies depending upon the population in which it is calculated. Despite the likely heterogeneity existing between methods of diagnosis, the prevalence of CAFRs in companion animals appears somewhat similar. Among dogs and cats with any disease, skin disease, pruritus or allergic skin disease, the median prevalence of CAFR is less than 1%, about 5%, between 15 to 20% and 10 to 25%, respectively; it is also estimated to be around one third of dogs with atopic dermatitis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Pascal Prélaud for participating in the original concept of this CAT, and Royal Canin for paying publication charges for this article.

Authors’ contributions

The two authors selected the topic of this CAT. TO performed the literature search, extracted and summarized the evidence and wrote this article. RSM verified the results, and then reviewed, edited and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Competing interests

Both authors have lectured for, and received research funding and/or consulting honoraria from Royal Canin (Aimargues, France) in the last 5 years.

Abbreviations

- CAFR

Cutaneous adverse food reaction

- CAT

Critically appraised topic

Additional files

Specific data on the prevalence of CAFRs among dogs with various conditions. (XLSX 45 kb)

Specific data on the prevalence of CAFRs among cats with various conditions. (XLSX 40 kb)

References

- 1.Scott DW, Paradis M. A survey of canine and feline skin disorders seen in a university practice: Small Animal Clinic, University of Montreal, Saint-Hyacinthe, Quebec (1987–1988) Can Vet J. 1990;31:830–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kunkle G, Horner S. Validity of skin testing for diagnosis of food allergy in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;200:677–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denis S, Paradis M. L’allergie alimentaire chez le chien et le chat. 2. Etude rétrospective (food allergy in dogs and cats. 2. retrospective study) Méd Vét Québec. 1994;24:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vroom MW. A retrospective study of 45 west-highland-white terriers with skin problems. Tijdschr Diergeneeskd. 1995;120:292–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guilford WG, Markwell PJ, Jones BR, Harte JG, Wills JM. Prevalence and causes of food sensitivity in cats with chronic pruritus, vomiting or diarrhea. J Nutr. 1998;128:2790S–1S. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.12.2790S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesney CJ. Food sensitivity in the dog: a quantitative study. J Small Anim Pract. 2002;43:203–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2002.tb00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biourge BC, Fontaine J, Vroom MW. Diagnosis of adverse reactions to food in dogs: efficacy of a soy-isolate hydrolysate-based diet. J Nutrition. 2004;134:2062S–4S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.8.2062S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeffler A, Lloyd DH, Bond R, Kim JY, Pfeiffer DU. Dietary trials with a commercial chicken hydrolysate diet in 63 pruritic dogs. Vet Rec. 2004;154:519–22. doi: 10.1136/vr.154.17.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilhelm S, Favrot C. Futtermittelhypersensitivitäts-Dermatitis beim Hund: Möglichkeiten der Diagnose. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd. 2005;147:165–71. doi: 10.1024/0036-7281.147.4.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill PB, Lo A, Eden CA, Huntley S, Morey V, Ramsey S, Richardson C, Smith DJ, Sutton C, Taylor MD, Thorpe E, Tidmarsh R, Williams V. Survey of the prevalence, diagnosis and treatment of dermatological conditions in small animals in general practice. Vet Rec. 2006;158:533–9. doi: 10.1136/vr.158.16.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loeffler A, Soares-Magalhaes R, Bond R, Lloyd DH. A retrospective analysis of case series using home-prepared and chicken hydrolysate diets in the diagnosis of adverse food reactions in 181 pruritic dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2006;17:273–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2006.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nodtvedt A, Bergvall K, Emanuelson U, Egenvall A. Canine atopic dermatitis: validation of recorded diagnosis against practice records in 335 insured Swedish dogs. Acta Vet Scand. 2006;48:8. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-48-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noli C, Candian M, Scarpa P. Analysis of a dermatology specialty case log in Northern Italy: 1188 cases (1995–2002) (in Italian) Veterinaria (Cremona) 2006;20:39–52. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarpataki N, Papa K, Reiczigel J, Vajdovich P, Vorosi K. Prevalence and features of canine atopic dermatitis in Hungary. Acta Vet Hung. 2006;54:353–66. doi: 10.1556/AVet.54.2006.3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kotnik T. Retrospective study of presumably allergic dogs examined over a 1-year period at the Veterinary Faculty, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Vet Arhiv. 2007;77:453–62. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Počta S, Svoboda M. Incidence of canine hypersensitivity in the region of north eastern Bohemia. Acta Vet Brno. 2007;76:451–9. doi: 10.2754/avb200776030451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Picco F, Zini E, Nett C, Naegeli C, Bigler B, Rufenacht S, Roosje P, Gutzwiller ME, Wilhelm S, Pfister J, Meng E, Favrot C. A prospective study on canine atopic dermatitis and food-induced allergic dermatitis in Switzerland. Vet Dermatol. 2008;19:150–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2008.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Souza TM, Fighter RA, Schmidt C, Réquia AH, Brum JS, Martins TB, Barros CSL. Prevalência das dermatopatias não-tumorais em cães do município de Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul (2005–2008) Pesq Vet Bras. 2009;29:157–62. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salzo PS, Larsson CE. Hipersensibilidade alimentar em cães. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2009;61:598–605. doi: 10.1590/S0102-09352009000300012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proverbio D, Perego R, Spada E, Ferro E. Prevalence of adverse food reactions in 130 dogs in Italy with dermatological signs: a retrospective study. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51:370–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00951.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Favrot C, Steffan J, Seewald W, Picco F. A prospective study on the clinical features of chronic canine atopic dermatitis and its diagnosis. Vet Dermatol. 2010;21:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2009.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hobi S, Linek M, Marignac G, Olivry T, Beco L, Nett C, Fontaine J, Roosje P, Bergvall K, Belova S, Koebrich S, Pin D, Kovalik M, Meury S, Wilhelm S, Favrot C. Clinical characteristics and causes of pruritus in cats: a multicentre study on feline hypersensitivity-associated dermatoses. Vet Dermatol. 2011;22:406–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3164.2011.00962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khoshnegah J, Movassaghi AR, Rad M. Survey of dermatological conditions in a population of domestic dogs in Mashhad, northeast of Iran (2007–2011) Vet Res Forum. 2013;4:99–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scott DW, Miller WHJ. Cutaneous food allergy in cats: a retrospective study of 48 cases (1988–2003) Jpn J Vet Dermal. 2013;19:203–10. doi: 10.2736/jjvd.19.203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scott DW, Miller WHJ. Feline atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study of 194 cases (1988–2003) Jpn J Vet Dermatol. 2013;19:135–47. doi: 10.2736/jjvd.19.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogelnest LJ, Cheng KY. Cutaneous adverse food reactions in cats: retrospective evaluation of 17 cases in a dermatology referral population (2001–2011) Aust Vet J. 2013;91:443–51. doi: 10.1111/avj.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravens PA, Xu BJ, Vogelnest LJ. Feline atopic dermatitis: a retrospective study of 45 cases (2001–2012) Vet Dermatol. 2014;25:e27–8. doi: 10.1111/vde.12109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rondelli MCH, Oliveira MCC, DaSilva FL, Palacios RJGJ, Peixoto MC, Carciofi AC, Tinucci-Costa M. A retrospective study of canine cutaneous food allergy at a Veterinary Teaching Hospital from Jaboticabal, São Paulo, Brazil. Ciência Rural. 2015;45:1819–25. doi: 10.1590/0103-8478cr20140440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]