Abstract

Formation of the Drosophila embryonic termini is controlled by the localized activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase Torso. Both Torso and Torso's presumed ligand, Trunk, are expressed uniformly in the early embryo. Polar activation of Torso requires Torso-like, which is expressed by follicle cells adjacent to the ends of the developing oocyte. We find that Torso expressed at high levels in cultured Drosophila cells is activated by individual application of Trunk, Torso-like or another known Torso ligand, Prothoracicotropic Hormone. In addition to assays of downstream signaling activity, Torso dimerization was detected using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Trunk and Torso-like were active when co-transfected with Torso and when presented to Torso-expressing cells in conditioned medium. Trunk and Torso-like were also taken up from conditioned medium specifically by cells expressing Torso. At low levels of Torso, similar to those present in the embryo, Trunk and Torso-like alone were ineffective but acted synergistically to stimulate Torso signaling. Our results suggest that Torso interacts with both Trunk and Torso-like, which cooperate to mediate dimerization and activation of Torso at the ends of the Drosophila embryo.

KEY WORDS: Drosophila, Terminal, Receptor tyrosine kinase, RTK, Membrane attack complex perforin, MACPF

Summary: Evenly distributed Trunk protein and terminally localized Torso-like combine to promote spatially restricted dimerization and activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase Torso.

INTRODUCTION

The receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) Torso plays a crucial role in defining the terminal regions, the acron and telson, of the Drosophila melanogaster embryo (Nüsslein-Volhard et al., 1987; Sprenger et al., 1989; St. Johnston and Nüsslein-Volhard, 1992). Torso acts through the canonical Ras/Raf/MAP kinase (MAPK) pathway (Doyle and Bishop, 1993; Lu et al., 1993; Ambrosio et al., 1989; Brunner et al., 1994; Mishra et al., 2005), and in embryos from wild-type mothers two polar caps of phosphorylated MAPK are dependent upon Torso signaling (Gabay et al., 1997). Although Torso is activated only at the poles, it is uniformly distributed throughout the plasma membrane of the early embryo (Casanova and Struhl, 1989). The ligand for Torso in the embryo is thought to be Trunk (Trk), a secreted protein containing a cystine knot motif often found in secreted peptide growth factors (McDonald and Hendrickson, 1993; Casanova et al., 1995; Sun and Davies, 1995). trk and torso mRNAs are both expressed in the maternal germline (Sprenger et al., 1989; Casanova and Struhl, 1989) and mRNAs encoding both proteins are present in the early embryo at syncytial blastoderm stage, when the embryo is still a single cell. This raises the issue of how Torso and Trk interact productively only at the poles of the embryo.

A key component in determining the spatial specificity of Torso activation in the early embryo is the protein Torso-like (Tsl). Tsl is expressed during oogenesis in two groups of follicle cells that lie adjacent to the poles of the developing oocyte (Stevens et al., 1990; Savant-Bhonsale and Montell, 1993; Martin et al., 1994). Tsl is a secreted protein that carries a membrane attack complex/perforin (MACPF) domain found in a number of proteins known to oligomerize to form membrane pores (Ponting, 1999; Lukoyanova et al., 2016). Tsl becomes localized to the anterior and posterior regions of the vitelline membrane (VM) (Stevens et al., 2003): the inner layer of the eggshell that surrounds the developing embryo. In addition, Tsl has been detected in the membrane of the embryo at the anterior and posterior poles (Martin et al., 1994; Mineo et al., 2015). When tsl is ectopically expressed throughout the follicle cell layer, the resulting embryos exhibit phenotypes similar to those produced by the constitutively active torso gain-of-function alleles (Klingler et al., 1988; Savant-Bhonsale and Montell, 1993; Martin et al., 1994), suggesting that in wild-type embryos, Tsl determines where Torso is activated.

Trk exhibits similarity to Spätzle (Spz), another secreted cystine knot-containing protein (Casanova et al., 1995; Morisato and Anderson, 1994) that acts as the ligand for the Toll receptor in dorsal-ventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo. Spz is secreted into the perivitelline fluid surrounding the embryo as an inactive precursor (Stein and Nüsslein-Volhard, 1992; Schneider et al., 1994) that is cleaved to form an active ligand only on the ventral side of the embryo (LeMosy, 2006; Cho et al., 2010). Casali and Casanova (2001) identified several potential proteolytic cleavage sites in Trk and also reported that the expression of a ‘pre-cleaved’ C-terminal region of Trk activates Torso ectopically and does not require Tsl function. This led them to propose that Tsl controls Torso activation by mediating the cleavage of Trk into an active form only at the poles of the embryo. Henstridge et al. (2014) demonstrated that Trk does undergo processing in embryos, but at least some of the cleavage events are mediated by Furin proprotein convertases (Johnson et al., 2015) and are not Tsl dependent. Johnson et al. (2015) reported that secretion from the embryo of a fluorescent fusion protein containing N-terminal Trk sequences is enhanced by Tsl activity, leading them to propose that the role of Tsl is to promote secretion of Trk into the perivitelline fluid specifically at the two ends of the embryo.

Recently, it has been determined that Torso activation controls the initiation of metamorphosis at the end of the larval period (Rewitz et al., 2009) and the photophobic behavior exhibited by foraging and wandering larvae (Yamanaka et al., 2013). The ligand that activates Torso to regulate these two behaviors is prothoracicotropic hormone (PTTH) (Kawakami et al., 1990; Rewitz et al., 2009), a secreted cystine knot-containing peptide that is expressed in a bilateral pair of neurons in the brain. PTTH expressed in these neurons activates Torso in cells of the prothoracic gland (Siegmund and Korge, 2001; Rybczynski, 2005; McBrayer et al., 2007), in photoreceptive dendritic arborization neurons in the body wall of the larva (Xiang et al., 2010) and in cells of Bolwig's organ (Hassan et al., 2005; Mazzoni et al., 2005). Although the extent to which Tsl participates in the activation of Torso in the larval prothoracic gland remains controversial (Grillo et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2013), transgenic expression of PTTH in the embryo activates Torso in a Tsl-independent manner, leading to a terminalizing phenotype similar to that produced by Torso gain-of-function mutations. This raises the possibility that for normal embryonic development to occur, a mechanism exists to prevent Trk and Torso from interacting productively except at the poles of the embryo, where spatially localized Tsl overcomes this mechanism either by facilitating the Trk/Torso interaction or by overcoming an inhibitory mechanism that prevents the interaction.

To better understand the mechanism of Torso activation and the role of Tsl in this process, we established conditions for ligand-mediated activation of Torso in a Drosophila cell culture-based system. Using multiple assays, we found that when Torso was expressed at high levels in these cells, its activity could be induced by Trk or Tsl acting independently. When Torso concentrations in the cultured cells were lower, at levels more similar to those present in the embryo, activation by Trk or Tsl alone was no longer observed. However, under these conditions, a strong synergistic effect was detected when Trk and Tsl were present together. In addition, both Trk and Tsl mediated dimerization of Torso receptors, and tagged versions of Trk and Tsl were taken up from conditioned medium by Torso-expressing cells. Our data support a mechanism in which both Trk and Tsl play a direct role in promoting Torso dimerization and activation.

RESULTS

Trk, Tsl and PTTH can activate Torso-dependent transcription of a STAT92E-responsive reporter gene in cultured Drosophila cells

To define the individual contributions of Trk and Tsl to Torso activation, we sought to establish conditions that would permit the characterization of ligand-dependent stimulation of Torso in a cultured cell system. We used the Drosophila S2R+ tissue culture line (Schneider, 1972; Yanagawa et al., 1998), which has been used effectively in other studies examining ligand-mediated receptor activation (Yanagawa et al., 1998; Sims et al., 2009). In our initial studies, we chose to use a STAT92E reporter as our measure of Torso stimulation. STAT92E is activated at the posterior pole of the embryo in response to Torso signaling and is required for the proliferation and migration of primordial germ cells in early embryos (Li et al., 2003). In these studies, we employed a firefly luciferase (Fluc) reporter system, together with multicistronic vectors directing the expression of various Torso constructs singly or together with Trk, Tsl or PTTH (Fig. 1, see also supplementary Materials and Methods). Western blot analysis demonstrated that when the same transfection conditions were used, the levels of Torso protein expressed by the cells were similar regardless of whether Torso was expressed alone or together with Trk, Tsl, PTTH or Trk and Tsl (Fig. S1).

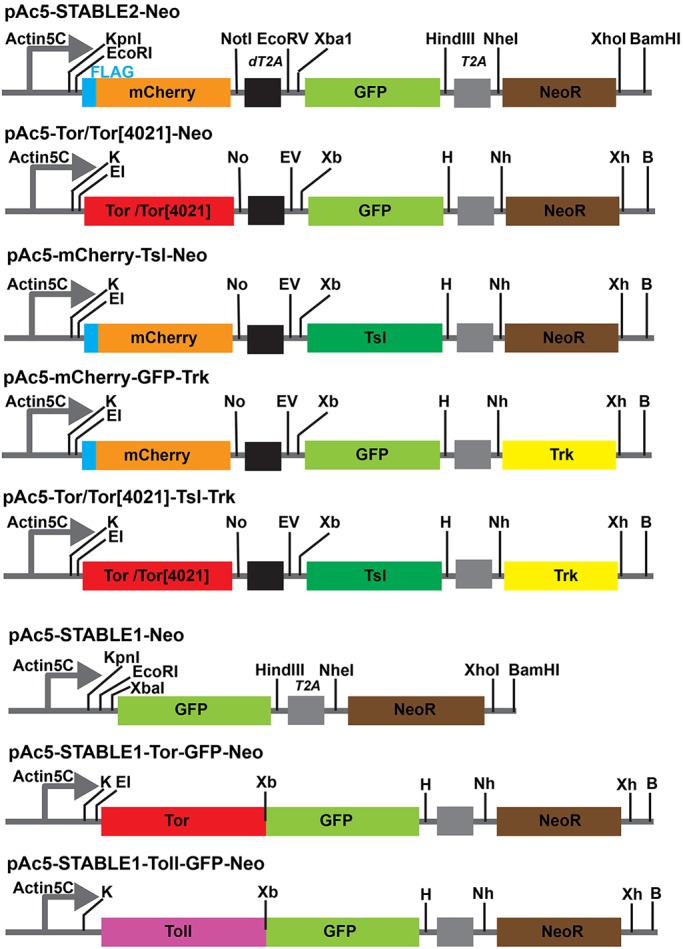

Fig. 1.

Strategy for cloning the Torso (Tor), Tsl and Trk open reading frames into the multicistronic expression vectors pAc5-STABLE2-Neo and pAc5-STABLE1-Neo. (Top row) Schematic diagram of the multicistronic segment of pAc5-STABLE2-Neo (Gonzalez et al., 2011), which contains the Actin5C promoter, and mCherry, GFP and NeoR genes, is shown. Restriction sites and the positions of the dT2A and T2A autocleavage sites (black and gray boxes, respectively) are shown. (Rows 2-5) Plasmid derivatives in which DNA fragments encoding wild-type Tor/Tor[4021], Tsl and/or Trk have been introduced. (Row 6) Schematic diagram of the bicistronic region of pAc5-STABLE1-Neo (Gonzalez et al., 2011), which carries the Actin5C promoter and GFP and NeoR open reading frames, with restriction sites indicated. (Row 7) The plasmid encoding a Tor-GFP fusion protein (pAc5-STABLE1-Tor-GFP-Neo), with the cloning sites that were used for the substitution displayed as well as other restriction sites that remain. pAc5-STABLE1-Toll-GFP-Neo, which encodes a Toll-GFP fusion protein, is shown in the last row. B, BamHI; E1, EcoRI; EV, EcoRV; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; Nh, NheI; No, NotI; Xb, XbaI; Xh, XhoI.

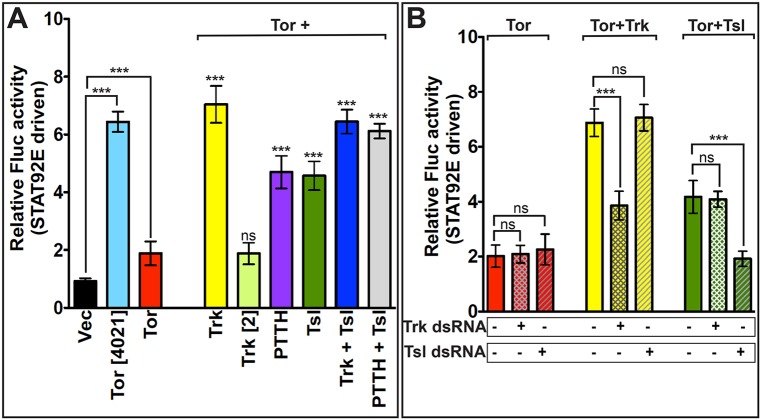

In an initial test of the ability of activated Torso to induce expression of the STAT92E reporter, we expressed the reporter construct together with either wild-type Torso, constitutively active Torso[4021] (Klingler et al., 1988; Sprenger and Nüsslein-Volhard, 1992) or with the pAc5-STABLE2-Neo vector alone. The Torso[4021] protein produced a strong level of induction, 6.5-fold over vector alone, indicating that Torso-mediated stimulation of STAT92E transcriptional activity is effectively detected in this tissue culture-based system (Fig. 2A). By contrast, expression of wild-type Torso was accompanied by only a modest, though significant, increase (∼1.75-fold) in Fluc activity over vector alone. Expression of Trk, Tsl or PTTH alone, in the absence of co-expressed Torso, did not increase Fluc activity relative to the vector control (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Tor-dependent activation of STAT92E-driven Fluc activity is induced by co-expression of Trk, PTTH or Tsl. All S2R+ cells were co-transfected with the STAT92E-dependent Fluc reporter construct and the RNA PolIII 128 promoter-dependent R-luc control plasmid for transfection normalization. Relative Fluc activity of each sample is calculated with respect to cells expressing vector alone. (A) Samples shown on the left-hand side were transfected with either the pAc5-STABLE2-Neo vector control plasmid (Vec) (black), or with the vector encoding Tor[4021] (light blue) or wild-type Tor (red). Samples on the right-hand side were transfected with a plasmid encoding wild-type Tor and the following genes: Trk (yellow), Trk[2] mutant (light green), PTTH (purple), Tsl (dark green), Trk plus Tsl (dark blue) or PTTH plus Tsl (gray). (B) Trk and Tsl activation of Tor-mediated STAT92E-driven Fluc activity does not depend upon endogenous trk or tsl expression in S2R+ cells. Cells were transfected with Tor alone (red), Tor plus Trk (yellow) or Tor plus Tsl (green) and treated with no added dsRNA (solid bars), dsRNA targeting trk (cross-hatched bars) or dsRNA targeting tsl (hatched bars). In A, each data point is an average of three replicates, repeated seven times (n=7). Significance values for Tor and Tor[4021] are determined relative to vector alone. In all other cases, significance has been calculated relative to cells expressing Tor alone. In B, each bar represents an average of three replicates, repeated five times (n=5). Relative Fluc activity is displayed as mean±s.d., based on seven (A) or five (B) replicate measurements. Differences in values that are statistically significant are indicated above the bars. ***P<0.001. ns, not significant.

The co-expression of Trk with wild-type Torso led to a fourfold increase in Fluc activity relative to Torso alone (Fig. 2A). However, wild-type Torso co-expression with a Trk protein containing the loss-of-function mutation found in trk2 (Casanova et al., 1995) did not increase Fluc activity over that induced by Torso alone. (All subsequent fold increases in Fluc activity reported here are relative to Torso alone unless specified otherwise.) We also tested the effect of co-expressing PTTH with Torso, which produced a 2.5-fold increase in Fluc activity. Surprisingly, co-expression of Tsl with Torso also led to a statistically significant 2.5-fold increase. However, when Tsl and Trk were simultaneously co-expressed with Torso, the 3.7-fold increase in Fluc activity was similar to that observed in experiments with only Torso and Trk, suggesting that an additional effect of Tsl is not detectable under these conditions. By contrast, when we co-expressed Tsl with PTTH and Torso, the 3.4-fold increase in Fluc activity was higher than that seen with just PTTH and Torso, possibly attributable to additive effects.

S2R+ cells have been reported to express trk (http://www.flyrnai.org/cgi-bin/DRSC_gene_lookup.pl), raising the possibility that some of the co-expression results described above were influenced by endogenous Trk protein. To address this issue, we generated dsRNA targeting the trk transcript and tested its ability to block Torso activation by co-expressed Tsl and Trk. For these experiments, we introduced Torso on a plasmid that was separate from the one bearing Trk, and confirmed that Fluc activity is stimulated when Torso and Trk or Torso and Tsl are introduced on separate plasmids (Fig. 2B). When dsRNA targeting Trk was included, the stimulation of Fluc activity induced by Tsl was unaffected, but the Trk-induced activity was substantially reduced. Similarly, the inclusion of dsRNA against Tsl interfered only with the ability of introduced Tsl to activate Torso. These results indicate that Tsl stimulation of Torso activity under these conditions does not depend on the presence of endogenous Trk protein.

Both Trk and Tsl direct Torso-dependent activation of the Ras/Raf/MAPK signaling pathway

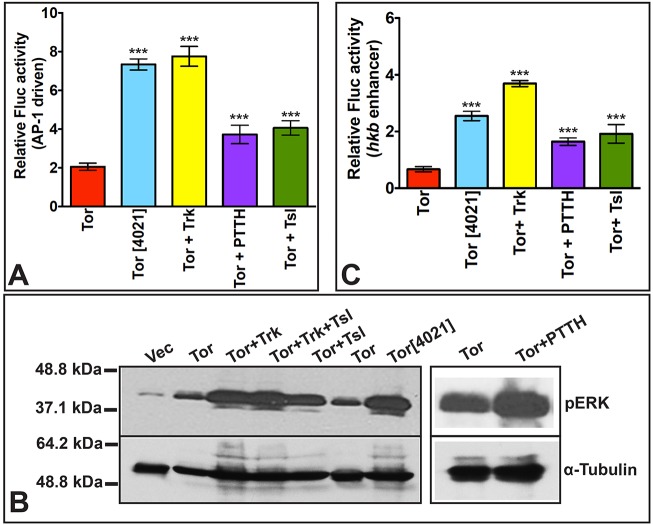

To determine whether in S2R+ cells the Ras/Raf/MAPK pathway was being recruited in response to Torso activation, we used a Fluc reporter construct that is sensitive to the transcription factor AP-1 (Chatterjee and Bohmann, 2012), which has been shown to be regulated by MAPK in Drosophila (Peverali et al., 1996; Kockel et al., 1997; Ciapponi et al., 2001; Gritzan et al., 2002). Wild-type Torso alone led to a modest (two-fold) induction of AP-1-Fluc activity over vector alone, whereas Torso[4021] produced a larger (7.5-fold over vector alone) increase (Fig. 3A). Also consistent with our initial studies, we found that co-expression of Trk with Torso produced a strong (3.9-fold) increase in reporter activity over that elicited by Torso alone, whereas Torso co-expression with PTTH or Tsl resulted in more modest increases of 1.9 and 2-fold, respectively. Corresponding results were seen in a western blot analysis using an antibody directed against activated, doubly phosphorylated (p44/42) MAPK/pERK protein (Fig. 3B). Thus, activation of Drosophila Torso in S2R+ cells leads to the recruitment and activation of the Ras/Raf/MAPK pathway.

Fig. 3.

Trk, PTTH and Tsl stimulate Tor activation of AP1- and hkb enhancer-driven Fluc activity and MAPK phosphorylation. (A,C) S2R+ cells were co-transfected with the R-luc transfection control plasmid and an AP-1-dependent Fluc reporter (A) or an hkb enhancer-driven Fluc reporter (C). The experimental plasmid(s) that each set of transfected cells received is shown below each bar. Data represent average±s.d. of three readings, repeated seven times (n=7). Statistical significance was determined with respect to relative Fluc activity in cells expressing Tor alone. ***P<0.001. (B) Western blot analysis of extracts from S2R+ cells transfected with plasmids expressing the proteins shown at the top of each lane. Homogenates were divided in half and run on duplicate gels that were blotted and probed with either anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK/pERK (top panels) or anti-α-Tubulin as a loading control (bottom panels).

As an additional test of the ability of S2R+ cells to reflect the normal embryonic context of Tor-induced transcriptional regulation, we generated a reporter construct containing the transcriptional elements responsible for polar embryonic expression of the Torso target gene hkb (Häder et al., 2000). For reasons that are not clear, the Fluc activity produced by this reporter was modestly decreased by the introduction of Torso alone, relative to vector. Nevertheless, the fold increases in activity that were detected in response to Trk, PTTH and Tsl co-expression with Torso corresponded well with those described above for the STAT92E- and AP-1-Fluc reporter constructs (Fig. 3C).

Torso is activated by Trk and Tsl present in culture media

Our finding that Torso is activated when co-expressed with either Trk or Tsl suggests that both Trk and Tsl have the capacity to influence Torso receptor activation independently. As these studies relied upon co-expression, this raised the possibility that the effects that we observed were due to intracellular interactions, perhaps within the secretory pathway, that normally may not occur between these molecules in the embryo. To investigate this possibility, we tested whether exogenously added Trk or Tsl could induce Torso signaling by collecting conditioned medium (CM) from cells expressing Trk or Tsl and adding it to Torso-expressing cells. We found that CM from either Trk- or Tsl-expressing cells activated STAT92E- and AP-1-directed Fluc activity (Fig. 4, Fig. S3), suggesting that both Trk and Tsl are capable of independently activating Torso when supplied in the extracellular environment.

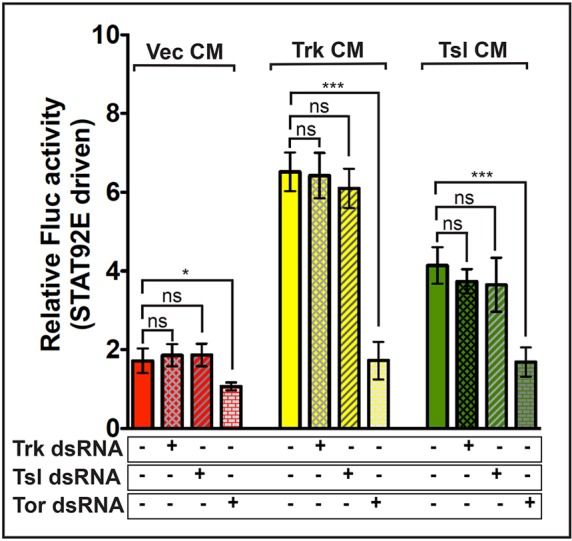

Fig. 4.

CM from Trk- or Tsl-expressing cells induces Tor-dependent activation of STAT92E-driven Fluc activity. CM from cells transfected with vector (Vec) (red), Trk (yellow) or Tsl (green) was applied to S2R+ cells expressing Tor together with the STAT92E-Fluc and R-luc constructs. Some recipient cells were additionally treated with dsRNA targeting Trk (cross-hatched bars), Tsl (hatched bars) or Tor (brickwork bars). Each bar represents an average of three replicates, repeated five times (n=5)±s.d. Comparisons with statistically significant differences are indicated above the bars. *P≤0.05 (P=0.0102), ***P≤0.001. ns, not significant.

To address the possibility that the effect of Tsl CM was mediated by endogenous Trk in the Torso-expressing cells, we repeated the CM experiments while also exposing the recipient cells to dsRNA directed against Trk, Tsl or Torso. In these experiments, only dsRNA targeting Torso reduced the levels of Torso activation elicited by the addition of Tsl CM (Fig. 4). We similarly used dsRNA targeting Trk to rule out the possibility that endogenous Trk in the CM-producing cells was responsible for the effect of Tsl CM (Fig. S4). Taken together, these findings suggest that extracellular Trk and Tsl can independently stimulate Torso activation.

Both Trk and Tsl promote Torso dimerization

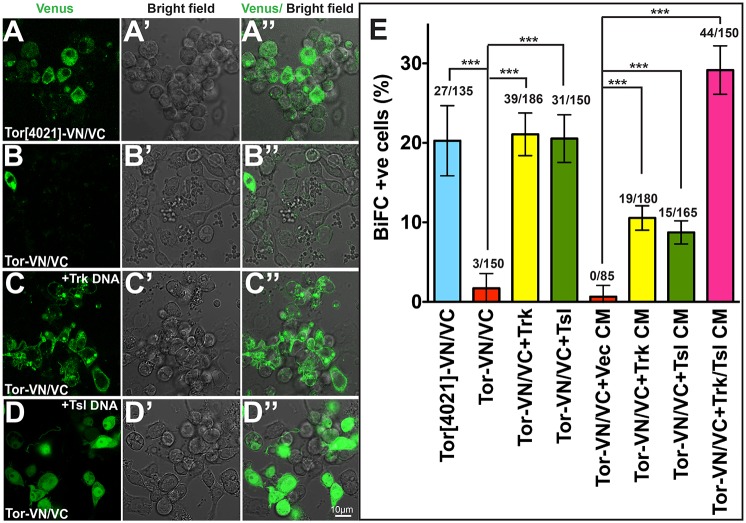

According to the prevailing model for RTK activation, most RTKs exist as monomers in a conformation that prevents dimerization, and ligand binding induces a conformational change that promotes receptor dimerization and subsequent cross-phosphorylation (Ullrich and Schlessinger, 1990; Lemmon and Schlessinger, 2010). To examine whether dimerization of Torso in response to Trk or Tsl could be detected in our system, we used bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) (Hu et al., 2002; Kodama and Hu, 2010; Tao and Maruyama, 2008; Shen and Maruyama, 2012), a method for visualizing interactions between proteins via dimerization-mediated complementation of split fluorescent proteins. We generated constructs to express wild-type and Torso[4021] sequences fused to either the N-terminal 155 amino acids (VN) or the C-terminal 84 amino acids (VC) of the fluorescent protein Venus.

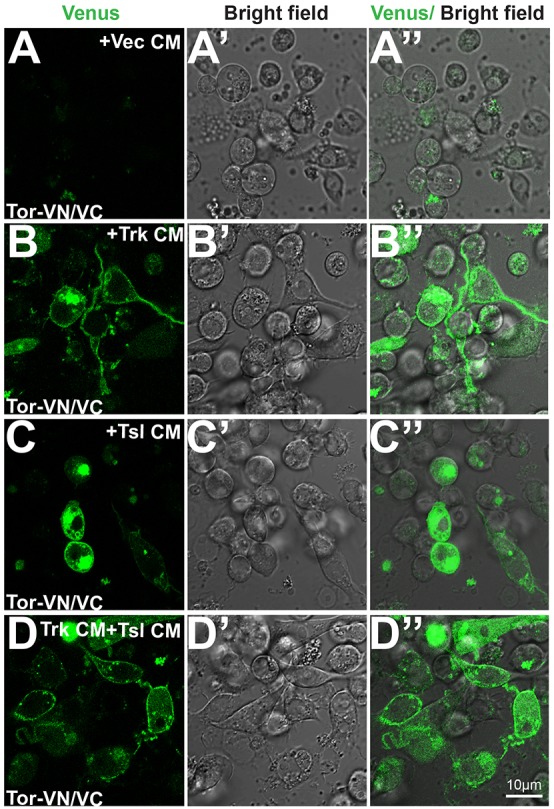

Cells expressing only the VN or VC version of either wild-type Torso or Torso[4021] did not exhibit fluorescence, regardless of the addition of Trk or Tsl (Fig. S5). By contrast, cells expressing both Torso[4021]-VN and Torso[4021]-VC in the absence of either Trk or Tsl exhibited abundant fluorescence (Fig. 5A). As Torso[4021] activation is ligand independent, this validates the use of BiFC to detect dimerization associated with receptor activation in this system. When wild-type Torso-VN and Torso-VC were co-expressed, a small percentage (2.0%) of cells exhibited fluorescence (Fig. 5B,E), consistent with the low level of activation seen in our reporter assays when Torso was expressed alone. The co-expression of either Trk or Tsl with Torso-VN plus Torso-VC led to a significant increase (to 21.0% and 20.7%, respectively) in the percentage of fluorescent cells (Fig. 5C-E). A similar trend was seen in experiments in which CM from cells expressing Trk or Tsl was added to cells expressing both Torso-VN and Torso-VC (10.6% and 9.1% fluorescent cells, respectively) (Fig. 5E; Fig. 6A-C). Interestingly, the combination of Trk CM plus Tsl CM elicited the strongest response that we detected (29.3% fluorescent cells) (Fig. 5E; Fig. 6D). These observations suggest that Trk and Tsl induce Torso activation by promoting dimerization of the receptor.

Fig. 5.

Co-expression with Trk or Tsl leads to dimerization of Tor. (A-D″) Fusion proteins between Tor and the Venus protein N-terminus (VN) or C-terminus (VC) were co-expressed either alone or with Trk or Tsl. The appearance of Venus fluorescence indicates that dimerization of Tor receptors has occurred. The left column shows Venus fluorescence, the middle column shows bright-field images and the right column displays an overlay of the two. (A-A″) Co-expression of Tor[4021]-VN and Tor[4021]-VC. (B-D″) Co-expression of wild-type Tor-VN and Tor-VC in the absence of other introduced genes (B-B″), with Trk (C-C″) or with Tsl (D-D″). Scale bar: 10 μm. (E) Quantitation of the percentage of cells that exhibited bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) (see also Fig. 6). Data are mean±s.d. derived from three independent replicate experiments (n=3). The total number of cells counted is shown above each bar. ***P≤0.001.

Fig. 6.

Exogenously added Trk or Tsl induces dimerization of Tor. (A-D″) Cells co-expressing wild-type Tor-VN/Tor-VC were exposed to CM from cells transfected with vector alone (Vec) (A-A″) or cells expressing Trk (B-B″), Tsl (C-C″) or both Trk and Tsl (D-D″). The left column shows Venus fluorescence, the middle column shows a bright-field image and the right column displays an overlay of the two. Scale bar: 10 μm. (See Fig. 5E for quantitation.)

Trk and Tsl bind S2R+ cells in a Torso-dependent manner

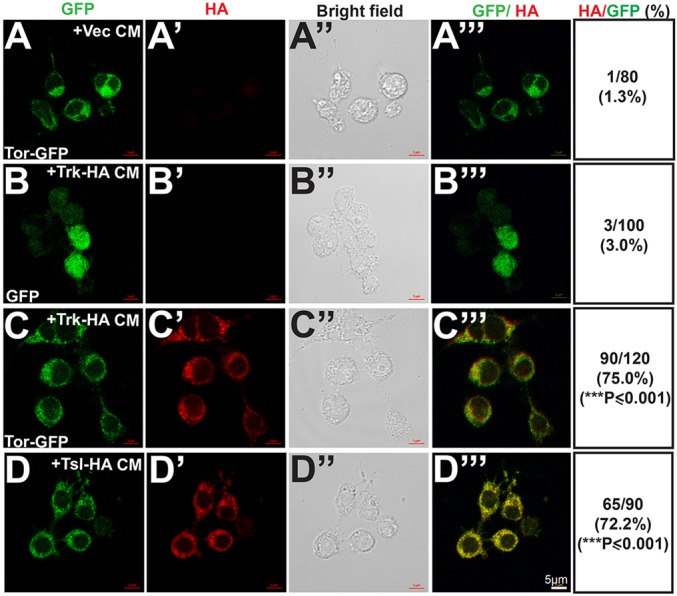

If the activation of Torso by Trk and Tsl in our cell-based assay reflects a direct interaction between these proteins and Torso, we would expect exogenously added Trk and Tsl to be detected on the surface of, or within, Torso-expressing cells. To test this, we expressed HA-tagged versions of Trk (Trk-HA) and Tsl (Tsl-HA) and confirmed that they were competent to induce STAT92E-mediated Fluc activity in Torso-expressing S2R+ cells (data not shown). We then collected CM from cells expressing the HA fusion proteins, applied it to Torso-expressing cells and processed the cells for immunohistochemical detection of the HA-tagged proteins. In these experiments, Torso was expressed as a GFP fusion protein (Torso-GFP) to allow identification of cells expressing detectable levels of the receptor. Many Torso-GFP expressing cells exposed to Trk-HA or Tsl-HA CM exhibited strong HA staining (Fig. 7C-D‴): 75.0% and 72.2%, respectively. Control cells expressing GFP without Torso sequences did not exhibit detectable HA staining after exposure to Trk-HA or Tsl-HA CM (Fig. 7B-B‴, data not shown), nor did Torso-GFP expressing cells that had been exposed to CM from cells expressing vector alone (Fig. 7A-A‴). As an additional control for the specificity of the interaction, we applied Trk-HA and Tsl-HA CM to cells expressing a GFP-tagged version of the Drosophila Toll receptor (Fig. S6A-B‴). No HA staining of these cells was detected, but when Toll-GFP-expressing cells were incubated with CM containing an HA-tagged version of processed active Spz (SpzΔN-HA), the ligand for Toll, HA immunofluorescence was observed (Fig. S6D-D‴). As expected, HA-tagged, full-length unprocessed Spz did not bind to cells expressing Toll-GFP (Fig. S6C-C‴) and SpzΔN-HA did not bind to cell expressing Torso-GFP (Fig. S6E-E‴). Collectively, these data are consistent with the idea that Trk and Tsl both interact directly with the Torso receptor.

Fig. 7.

Tor-expressing cells take up Trk and Tsl. (A-D‴) Cells expressing Tor-GFP (A-A‴,C-E‴) or GFP alone (expressed by pAc5-STABLE1-Neo) (B-B‴) were exposed to CM obtained from cells expressing vector alone (A-A‴), Trk-HA (B-C‴) or Tsl-HA (D-D‴). The cells were imaged for GFP fluorescence (A-D) and stained with anti-HA antibody (A′-D′). Bright-field images (A″-D″) and overlays of GFP and anti-HA staining (A‴-D‴) are also shown. For each study, the proportion of GFP- or Tor-GFP-expressing cells that also exhibited staining with anti-HA are shown in the last column. For each treatment, cells counted are the total of three independent experiments (n=3). Statistical significance was calculated relative to Tor-GFP-expressing cells treated with CM from vector control transfected cells. ***P≤0.001.

When Torso is present at low levels, Trk and Tsl act synergistically to activate the receptor

Our finding that Trk and Tsl are competent to activate Torso signaling independently is in stark contrast to the situation in wild-type embryos, where Trk and Tsl are both necessary to bring about Torso activation. The conditions that we used in the experiments described above were designed to ensure high transfection efficiency of multiple DNA components into individual cells. The resulting high levels of protein expression are unlikely to reflect the concentrations of Torso, Trk and Tsl present in Drosophila embryos. Indeed, our observation that expression of Torso alone produced a detectable increase in reporter activity suggests that the S2R+ cells were expressing levels of Torso considerably higher than that present in embryos, which we have confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. S7).

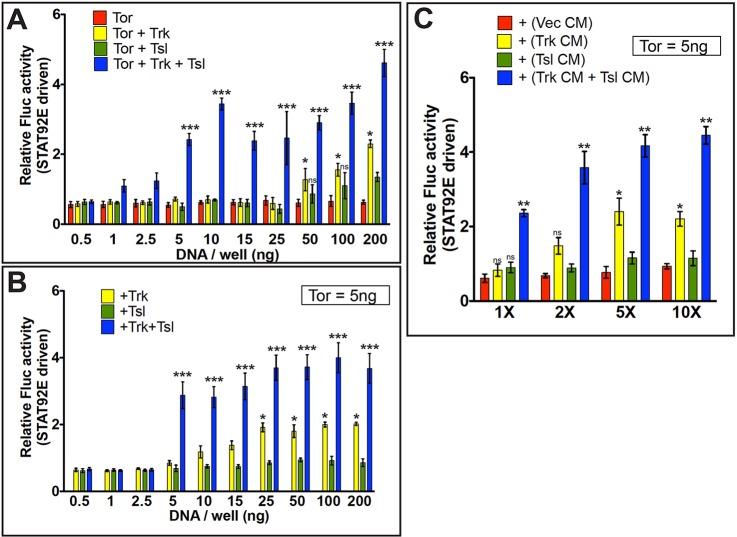

To investigate whether the expression level of Torso in the S2R+ cells influenced the ability of Trk and Tsl to individually activate Torso, we carried out a series of transfections with successively lower amounts of multicistronic constructs encoding either Torso alone, Torso plus Trk, Torso plus Tsl or Torso plus both Trk and Tsl. At transfected DNA concentrations of 25 ng/well and below, neither Trk nor Tsl alone elicited detectable activation of Torso. However, the simultaneous addition of both Trk and Tsl led to a highly significant increase in Fluc levels (Fig. 8A). A similar finding was observed in a second experiment in which the Trk and/or Tsl DNAs ranged from 0.5 ng to 200 ng, while the Torso DNA concentration was kept constant at 5 ng/well (Fig. 8B), which we have found to produce Torso protein levels comparable with those seen in Drosophila embryos (Fig. S7). Although some Torso activation was detected with Trk alone, much higher levels were observed when Trk and Tsl were co-expressed, even at concentrations as low as 5 ng/well. Similar results were obtained using the AP-1-Fluc reporter (Fig. S8A).

Fig. 8.

Trk and Tsl synergize to activate Tor-dependent STAT92E-driven Fluc in cells expressing low levels of Tor. (A-C) S2R+ cells were co-transfected with STAT92E-Fluc/R-luc constructs and the level of STAT92E-directed Fluc expression was assessed. (A) S2R+ cells were additionally transfected with increasing amounts of plasmid DNA carrying Tor (red), Tor plus Trk (yellow), Tor plus Tsl (green) or Tor plus both Trk and Tsl (blue). (B) S2R+ cells were transfected with 5 ng of the Tor expression plasmid plus a concentration range of plasmids bearing Trk alone (yellow), Tsl alone (green) or Trk plus Tsl (blue). (C) S2R+ cells in all samples were transfected with 5 ng of the Tor expression plasmid and exposed to control CM from cells transfected with vector alone (red), CM from cells expressing Trk (yellow) or Tsl (green), or a 1:1 mixture of Trk and Tsl CM (blue). CM was either untreated (1×), or was concentrated by various amounts (2× to 10×). Data are mean±s.d. of three readings, repeated five times (n=5). Statistical significance was calculated with respect to relative Fluc activity for cells expressing Tor alone at the appropriate experimental concentration (0.5-200 ng/well) (A), Tor alone at 5 ng/well (B), or Tor alone (5 ng/well) plus control vector CM at the correct experimental concentration (1-10X concentrated) (C). (A) ***P=0.0010, *P=0.036. (B) *P=0.0202, ***P=0.0082. (C) **P=0.0086, *P=0.0421. ns, not significant.

To determine whether the synergistic effect of Trk and Tsl co-expression could be detected when they were expressed independently and presented to Torso from the extracellular environment, we expressed Trk and Tsl separately in transfected S2R+ cells and collected CM from these cells. We then tested the ability of the CM, at various folds of concentration, to induce Fluc activity in cells expressing Torso (5 ng/well) (Fig. 8C). In unconcentrated CM, neither Trk nor Tsl alone was capable of producing significant Torso activation. However, when unconcentrated CM from the Trk- and Tsl-expressing cells was combined 1:1 and applied to Torso-expressing cells, a marked increase in Fluc activity was observed. We observed a similar synergistic interaction between Trk CM and Tsl CM using the hkb-Fluc reporter (Fig. S8B). Taken together, these findings indicate that when Torso, Trk and Tsl are present at low levels, a situation that more closely approximates the conditions in the embryo, neither Trk nor Tsl can effectively activate Torso independently. However, when both are present in the extracellular environment they can act synergistically to induce receptor activation.

As described earlier, PTTH induced Fluc activity in S2R+ cells expressing high levels of Torso. By contrast, when Torso DNA was transfected at 5 ng/well, no amount of co-transfected PTTH DNA, up to 200 ng/well, was capable of activating Torso, as measured using the STAT92E (Fig. S9A) and AP-1 reporters (Fig. S9B). The co-expression of Tsl with PTTH also produced no activation under these conditions. A possible explanation for the discrepancy is that PTTH expressed in S2R+ cells may not be processed into its mature active form and consequently may be a relatively weak activator of Tor (see Discussion).

DISCUSSION

Previous models for Torso activation in the embryo have suggested that Tsl exerts its effects through Trk, either by promoting its processing (Casali and Casanova, 2001) or by facilitating its secretion at the poles (Johnson et al., 2015). Although our experiments in S2R+ cells do not necessarily reflect the situation in the embryo, our results suggest that Tsl is likely to play another role, possibly in addition to effects on Trk processing/secretion. First, when Torso is expressed at high levels, Tsl can activate Torso in the absence of Trk, and it can do so both when it is co-expressed in the same cells as Torso and when it is present in the extracellular medium. In these experiments, RNAi targeting of trk mRNA was employed to ensure that the effect of Tsl was not mediated through Trk. Although Tsl cannot activate Torso independently when Torso is present at low concentrations, Tsl and Trk can synergize to bring about Torso activation at concentrations of the two proteins that are insufficient to activate Torso on their own. In this set of experiments, the synergy between Trk and Tsl was seen both when the proteins were co-expressed together with Torso, and when they were expressed separately, collected in the medium and combined before presentation to Torso-expressing cells. Thus, in these experiments, Tsl enhanced the function of Trk that had already been secreted into the medium.

It is imperative for normal embryonic development that Trk does not activate Torso ectopically. Thus, this pathway has evolved a mechanism in which Tsl function is required for Trk and Torso to engage in a productive interaction. As Tsl is localized to the poles of the embryo, this mechanism restricts Torso activation to the embryonic termini. Some insight into how Tsl might act can be gained by considering the structural differences between the two Torso ligands Trk and PTTH. Both are predicted to form a cystine knot structure, but there are important differences in the arrangement of these cysteine residues. PTTH has been shown to bind as a dimer to Bombyx mori Torso (Jenni et al., 2015). Although Drosophila Trk would also be expected to form a homodimer, the pattern of cysteine residues in Trk more closely resembles that of the Spz ligand, in which a different cysteine residue from the one used in PTTH participates in dimer formation (Hoffman et al., 2008). This and other structural differences between Trk and PTTH may significantly affect the affinity of the Torso/Trk interaction in comparison with Torso/PTTH interactions, bringing about a requirement for Tsl.

It was surprising that Trk and Tsl can independently activate Torso in cell culture when in the embryo both proteins are essential for Torso activation. In our experiments, independent activation of Torso by Trk or Tsl was most prominent when Torso was present at high levels, a condition that is likely to facilitate receptor dimerization. Indeed, when Torso was expressed alone we saw an almost twofold increase in reporter activity relative to vector control. Although some receptor tyrosine kinases remain in a monomeric state until binding of ligand leads to dimerization (Ullrich and Schlessinger, 1990; Lemmon and Schlessinger, 2010), others are present in an inactive dimeric state with a conformation in which the intracellular domains of the two proteins are unable to interact productively in the absence of ligand (Ward et al., 2007; Tao and Maruyama, 2008; Shen and Maruyama, 2012). Recently, it has been reported that B. mori Torso expressed in Drosophila S2 cells undergoes ligand-independent dimerization via disulfide linkages formed by cysteine residues present in the transmembrane domain (Konogami et al., 2016). Konogami et al. (2016) suggest that these disulfide bonds hold the dimerized Torso receptors in an inactive conformation that is released upon ligand binding. If Torso exists as an inactive dimer prior to ligand binding, a relatively small alteration in receptor conformation following the binding of Trk or Tsl might result in detectable receptor activation.

The situation is very different when Torso is present at low levels, which is more similar to the conditions in the embryo. Jenni et al. (2015) reported that the binding of the B. mori PTTH dimer to the first Torso monomer exhibited much higher affinity than the subsequent binding of the second Torso monomer required to complete the complex and allow signaling to occur. In this situation, the concentration of the receptor, rather than that of the ligand, determines the likelihood of an active complex forming. Thus, the requirement for both Trk and Tsl in the Drosophila embryo may reflect conditions in which Trk acts as the ligand for Torso, but due to negative cooperativity, Tsl is required to enhance the initial Trk/Torso interaction and/or facilitate the completion of Torso dimerization. It has not been determined whether the interaction of Trk and Torso in Drosophila exhibits negative cooperativity. However, even in the absence of this property, when Torso concentrations are low, Tsl may be necessary to locally concentrate Trk and/or to bind Trk in association with Torso. In this respect, Tsl may be functioning like Dally and Dally-like, Drosophila orthologs of vertebrate glypican proteoglycans, which act as co-receptors for the peptide growth factors Dpp (Fujise et al., 2003) and Wingless (Lin and Perrimon, 1999; Franch-Marro et al., 2005), and for FGF (Yan and Lin, 2007) and Hedgehog (Yan et al., 2010), respectively. Another intriguing possibility is that in the early embryo, under conditions of low Torso concentrations, Tsl promotes the formation of Torso dimers at the poles that are either inactive or only very weakly active. The presence of these pre-formed dimers could enhance the probability of Trk forming a productive interaction with Torso, which would be particularly important if the concentration of Trk is limiting, as has been reported (Sprenger and Nüsslein-Volhard, 1992). A similar mechanism has been proposed for the enhancement of VEGF-mediated activation of VEGFR2 by the transmembrane glycoprotein Emprin/CD147 (Khayati et al., 2015).

Alternatively, the role of Tsl may be dependent upon its affinity for membranes. Tsl has been detected in the plasma membrane at the two ends of the early embryo (Martin et al., 1994; Mineo et al., 2015) and Tsl bears a MACPF motif (Ponting, 1999), which is found in proteins known to become inserted into lipid bilayers (Lukoyanova et al., 2016). One possibility is that Tsl may modulate the local membrane environment in which Torso resides, perhaps by organizing lipid microdomains and thereby driving the formation of complexes competent to signal. This function would be similar to that of Caveolin, which interacts directly with the Insulin receptor (Kimura et al., 2002). Caveolin is involved in the formation of caveolae, lipid raft-containing microdomains in which Insulin receptor signaling is activated (Saltiel and Pessin, 2003; Strålfors, 2012).

The ability to control the expression levels of Torso, Trk and Tsl in cultured cells has allowed new insights into Torso activation to be obtained, specifically permitting conditions under which Tsl alone can activate Torso signaling and facilitate Torso dimerization. The ability of cells to take up Tsl-HA in a Torso-dependent manner provides strong evidence of a direct interaction between the two proteins. It remains possible that the novel observations we have made are limited to conditions in cultured cells and do not reflect the situation in the embryo. However, if these observations do extend to the control of Torso signaling in Drosophila embryos, direct regulation of receptor tyrosine kinase dimerization and activation would represent a novel function for a member of the MACPF class of proteins. This raises the possibility of other pathways in which Tsl influences the activity of Torso or other receptors in Drosophila, and of similar MACPF/receptor tyrosine kinase interactions operating in vertebrates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA constructs

DNA constructs encoding multicistronic messages expressing Torso, Tsl, Trk and/or PTTH were based on the vector pAc5-STABLE2-Neo (González et al., 2011) (Fig. 1), a gift from Rosa Barrio and James Sutherland (CIC bioGUNE, Technology Park of Bizkaia, Derio, Spain; Addgene, plasmid number 32426). Open reading frames introduced into this vector are transcribed as a single multicistronic message in which the individual open reading frames are separated by T2A cis-acting hydrolase elements that mediate the co-translational self-cleavage of the initial polyprotein translation product into individual proteins (Donnelly et al., 2001). During translation, cleavage of T2A sequences immediately upstream of secretory signal peptides results in the formation of free signal peptides that direct normal secretion of their associated peptides (de Felipe and Ryan, 2004). Detailed descriptions of the construction of these and other DNA constructs generated for these studies can be found in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Cell culture, transfection and reporter assays

Drosophila S2R+ cells were obtained from the Drosophila Genome Research Center (DGRC) and cultured in Schneider's Drosophila medium (Gibco, #21720-024) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Gibco, #A31604-01) at 25°C in a humidified incubator.

S2R+ cells were seeded at 5×105 cells/well in a six-well plate and transfected the following day at a density of 106 cells in 1.8 ml medium. Transient transfection was carried out using Effectene (Qiagen, #301427) with a DNA:enhancer ratio of 1:8 and a total of 1.9-2.0 µg DNA per well in a six-well plate format for Fluc reporter assays. In the initial experiments at high Torso concentrations, 1.25 µg of the pAc5-STABLE2-Neo-based expression vector was used. For BiFC experiments, a total of 2-2.5 µg DNA per well was used. Typically, a 200 µl transfection mix was used per well containing 1×106/ml cells in 2 ml medium. All transfections were performed in triplicate. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were harvested for reporter assays using Dual Glo reagents (Promega, #E2920). The luminescence was measured on a Luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Mithras LB 940) using the Mikrowin 2000 program. The relative luciferase units (RLUs) were calculated for each well as a ratio of Fluc to R-luc as described in the Promega literature accompanying the Dual Glo reagents. Relative Fluc activity was determined by dividing the average experimental RLU measurement for three wells of cells undergoing a particular experimental treatment by the average RLU value produced by three wells of cells transfected with vector alone during the same series of measurements. For all graphs, relative Fluc activity for cells transfected with vector control is therefore set to 1. Statistical significance in differences between cells receiving a particular experimental treatment was calculated using unpaired t-test with two-tailed P value after ascertaining that the data follows normal distribution using D'Agostino & Pearson, Shapiro-Wilk and Kologorov-Smirnov normality tests on Graphpad prism software. Each experiment was replicated at least five times in triplicate (n=5 for the purpose of determining standard deviation), accompanied by control measurements of activity directed by cells lacking Torso (pAc5-STABLE2-Neo) and by cells expressing Torso alone (pAc5-Tor [WT]-GFP-Neo), also both tested at least five times in triplicate.

RNA interference

dsRNAs used in these studies were generated by direct in vitro transcription of PCR products corresponding to sequences contained within target mRNAs. Each of the oligonucleotides used in these amplification reactions carried at their 5′ ends the sequence 5′TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG3′, which corresponds to the bacteriophage T7 promoter. Using the PCR products thus generated, dsRNAs were generated using the Megascript T7 transcription kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For assays in which RNAi was applied, 5 µl of dsRNA (3 µg/µl stock) were added to 3×106 ml cells/ml per well and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the DNA transfection mix for the reporter assays was added. The reporter assays were carried out 72 h post-transfection. The sequences of oligonucleotides used for the generation of dsRNA can be found in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Preparation of conditioned medium

For experiments using conditioned medium (CM), S2R+ cells were transfected as described above. The next day, medium was removed from the wells, the cells were rinsed once with PBS and fresh medium was added. Cells were then grown for two additional days. The cells were dislodged by pipetting once with a 5 ml pipette. The medium was then collected from the wells, the cells were pelleted and the supernatant (CM) used either unconcentrated or concentrated 2×, 5× or 10× using Amicon Ultra-15 columns (Ultracel-10 K, #UFC901008). In the experiment testing whether CM from Trk- and Tsl-expressing cells functions synergistically to activate Torso, unconcentrated Trk and Tsl CM were either mixed one to one with each other or with CM from cells transfected with vector alone. To make CM for this experiment, cells were transfected with 1 µg of one of the vectors pAc5-mCherry-GFP-Trk, pAc5-mCherry-Tsl-Neo or pAc5-mCherry-GFP-Neo.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation

For bimolecular fluorescence complementation studies, the modified Torso constructs bearing the N- and C-terminal segments of Venus cloned in the pUASp vector (Rørth, 1998) were co-transfected with 1.2 µg of the plasmid pMT-Gal4 (Klueg et al., 2002), which enables copper-inducible expression. Expression of the Torso-VN/VC constructs was induced by addition of copper sulfate solution to a final concentration of 0.7 mM 6 h after transfection. Forty-eight hours post-transfection the cells were imaged on a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope at 63× magnification. When Trk or Tsl were provided as DNA cloned on the pAc5-STABLE2-Neo vector, they were included in the transfection mix at 800 ng/well. When Trk or Tsl were presented in CM, the CM was added to the recipient cells 20 h after the transfection of pMT-Gal4.

Immunoblotting

Homogenates of cultured cells or embryos were subjected to SDS-PAGE, then transferred to nitrocellulose blotting membranes (Amersham Protran Premium, GE Healthcare Life Sciences), followed by western blot analysis using the following primary antibodies: rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4370S), mouse anti-∝-Tubulin (1:1000, Sigma, clone DM1A #T6199), rabbit polyclonal anti-Torso (1:4500, a kind gift from Frank Sprenger, University of Regensburg, Germany) (Sprenger and Nüsslein-Volhard, 1992). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies produced in goat and directed against rabbit (1:5000, Jackson Labs, #111035003) and mouse (1:5000, Thermo Scientific, #31430) antibodies, respectively, were used. The blots were developed using Supersignal West Pico reagents (Thermo Scientific, #34080) and detected with X-ray film or using a Li-COR C-DiGit Blot Scanner. A more detailed description of the immunoblotting protocol can be found in the supplementary Materials and Methods.

Cell binding assays

S2R+ cells were transfected with pMT-Gal4, together with pUASp, or one of the pUASp-based constructs encoding HA-tagged versions of Trk, Tsl or Spz/SpzΔN, and plated on glass-bottomed six-well plates. Subsequently, CuSO4 was added to these cells to induce the expression of Gal4 and thus the expression and subsequent secretion of the HA-tagged proteins. CM from these cells was collected and applied to recipient cells expressing Tor-GFP, Toll-GFP or GFP. These cells were subsequently fixed and processed for staining using a mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Thermo Scientific, #26183, clone 2-2.2.14) (1:200 dilution) followed by Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes, #A11005) (1:250 dilution), then imaged directly in their wells using a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope at 63× magnification. See also supplementary Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dirk Bohmann, Jordi Casanova, Rafael Fernandez, Chang-Deng Hu, Norbert Perrimon (Addgene plasmid numbers 32380, 37393), Frank Sprenger, Gary Struhl, James Sutherland (Addgene plasmid number 32426) and the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (supported by NIH grant 2P40OD010949-10A1) for plasmids and antibodies used in this study. Tissue culture lines used in this work were also supplied by the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center. We thank Daryl Klein for valuable discussion of this work. We also thank Evan Brown, Emily Flynn, Jeffrey Mayfield, Katherine Sieverman, Yuri Volnov and Xiaobin Wang for technical assistance in carrying out these studies.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

S.A., L.M.S. and D.S.S. initiated the study, designed the experiments and interpreted their results and wrote the manuscript. S.A. performed the experiments. D.S.S. contributed to the generation of DNA constructs used in these studies.

Funding

This work was supported by the March of Dimes Foundation (1-FY13-403 to D.S.S.) and the National Institutes of Health (RO1 GM077337 to D.S.S.). The Drosophila Genomics Resource Center is supported by the National Institutes of Health (2P40OD010949-10A1). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/doi/10.1242/dev.146076.supplemental

References

- Ambrosio L., Mahowald A. P. and Perrimon N. (1989). Requirement of the Drosophila Raf homologue for Torso function. Nature 342, 288-291. 10.1038/342288a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeg G.-H., Zhou R. and Perrimon N. (2005). Genome-wide RNAi analysis of JAK/STAT signaling components in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 19, 1861-1870. 10.1101/gad.1320705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner D., Oellers N., Szabad J., Biggs W. H. III, Zipursky S. L. and Hafen E. (1994). A gain-of-function mutation in Drosophila MAP kinase activates multiple receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways. Cell 76, 875-888. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90362-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali A. and Casanova J. (2001). The spatial control of Torso RTK activation: a C-terminal fragment of the Trunk protein acts as a signal for Torso receptor in the Drosophila embryo. Development 128, 1709-1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J. and Struhl G. (1989). Localized surface activity of Torso, a receptor tyrosine kinase, specifies terminal body pattern in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 3, 2025-2038. 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casanova J., Furriols M., McCormick C. A. and Struhl G. (1995). Similarities between Trunk and Spätzle, putative extracellular ligands specifying body pattern in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 9, 2539-2544. 10.1101/gad.9.20.2539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee N. and Bohmann D. (2012). A versatile φC31 based reporter system for measuring AP-1 and Nrf2 signaling in Drosophila and in tissue culture. PLoS ONE 7, e34063 10.1371/journal.pone.0034063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y. S., Stevens L. M. and Stein D. (2010). Pipe-dependent ventral processing of Easter by Snake is the defining step in Drosophila embryo DV axis formation. Curr. Biol. 20, 1133-1137. 10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciapponi L., Jackson D. B., Mlodzik M. and Bohmann D. (2001). Drosophila Fos mediates ERK and JNK signals via distinct phosphorylation sites. Genes Dev. 15, 1540-1553. 10.1101/gad.886301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Felipe P. and Ryan M. D. (2004). Targeting of proteins derived from self-processing polyproteins containing multiple signal sequences. Traffic 5, 616-626. 10.1111/j.1398-9219.2004.00205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly M. L. L., Hughes L. E., Luke G., Mendoza H., ten Dam E., Gani G. and Ryan M. D. (2001). The ‘cleavage’ activities of foot-and-mouth disease virus 2A site-directed mutants and naturally occurring ‘2A-like’ sequences . J. Gen. Virol. 82, 1027-1041. 10.1099/0022-1317-82-5-1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle H. and Bishop J. M. (1993). Torso, a receptor tyrosine kinase required for embryonic pattern formation, shares substrates with the sevenless and EGF-R pathways in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 7, 633-646. 10.1101/gad.7.4.633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W., Siegel V. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1990). Autonomous determination of anterior structures in the early Drosophila embryo by the bicoid morphogen. Development 109, 811-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franch-Marro X., Marchand O., Piddini E., Ricardo S., Alexandre C. and Vincent J. P. (2005). Glypicans shunt the Wingless signal between local signalling and further transport. Development 132, 659-666. 10.1242/dev.01639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujise M., Takeo S., Kamimura K., Matsuo T., Aigaki T., Isumi S. and Nakato H. (2003). Dally regulates Dpp morphogen gradient formation in the Drosophila wing. Development 130, 1515-1522. 10.1242/dev.00379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L., Seger R. and Shilo B.-Z. (1997). Map kinase in situ activation atlas during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development 124, 3535-3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González M., Martín-Ruíz I., Jiménez S., Pirone L., Barrio R. and Sutherland J. D. (2011). Generation of stable Drosophila cell lines using multicistronic vectors. Sci. Rep. 1, 75 10.1038/srep00075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillo M., Furriols M., de Miguel C., Franch-Marro X. and Casanova J. (2012). Conserved and divergent elements in Torso RTK activation in Drosophila development. Sci. Rep. 2, 272 10.1038/srep00762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritzan U., Weiss C., Brennecke J. and Bohmann D. (2002). Transrepression of AP-1 by nuclear receptors in Drosophila. Mech. Dev. 115, 91-100. 10.1016/S0925-4773(02)00116-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häder T., Wainwright D., Shandala T., Saint R., Taubert H., Brönner G. and Jäckle H. (2000). Receptor tyrosine kinase signaling regulates different modes of Groucho-dependent control of Dorsal. Curr. Biol. 10, 51-54. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)00265-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan J., Iyengar B., Scantlebury N., Rodriguez Moncalvo V. and Campos A. R. (2005). Photic input pathways that mediate the Drosophila larval response to light and circadian rhythmicity are developmentally related but functionally distinct. J. Comp. Neurol. 481, 266-275. 10.1002/cne.20383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henstridge M. A., Johnson T. K., Warr C. G. and Whisstock J. C. (2014). Trunk cleavage is essential for Drosophila terminal patterning and can occur independently of Torso-like. Nat. Commun. 5, 3419 10.1038/ncomms4419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman A., Funkner A., Neumann P., Juhnke S., Walther M., Schierhorn A., Weininger U., Balbach J., Reuter G. and Stubbs M. T. (2008). Biophysical characterization of refolded Drosophila Spätzle, a cystine knot protein, reveals distinct properties of the three isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 32598-32609. 10.1074/jbc.M801815200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C.-D., Chinenov Y. and Kerppola T. K. (2002). Visualization of interactions among bZip and Rel family proteins in living cells using bimolecular fluorescence complementation. Mol. Cell 9, 789-798. 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00496-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenni S., Goyal Y., von Grotthuss M., Shvartsman S. Y. and Klein D. E. (2015). Structural basis of neurohormone perception by the receptor tyrosine kinase Torso. Dev. Cell 60, 941-952. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. K., Crossman T., Foote K. A., Henstridge M. A., Saligari M. J., Beadle L. F., Herr A., Whisstock J. C. and Warr C. G. (2013). Torso-like functions independently of Torso to regulate Drosophila growth and developmental timing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 14688-14692. 10.1073/pnas.1309780110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. K., Henstridge M. A., Herr A., Moore K. A., Whisstock J. C. and Warr C. G. (2015). Torso-like mediates extracellular accumulation of Furin-cleaved Trunk to pattern the Drosophila embryo termini. Nat. Commun. 6, 8759 10.1038/ncomms9759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami A., Kataoka H., Oka T., Mizoguchi A., Kimura-Kawakami M., Adachi T., Iwami M., Nagasawa H., Suzuki A. and Ishizaki H. (1990). Molecular cloning of the Bombyx mori Prothoracicotropic Hormone. Science 247, 1333-1335. 10.1126/science.2315701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khayati F., Pérez-Cano L., Maouche K., Sadoux A., Boutalbi Z., Podgorniak M. P., Maskos U., Setterblad N., Janin A., Calvo F. et al. (2015). EMMPRIN/CD147 is a novel co-receptor of VEGFR-2 mediating its activation by VEGF. Oncotarget 6, 9766-9780. 10.18632/oncotarget.2870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A., Mora S., Shigematsu S., Pessin J. E. and Saltiel A. R. (2002). The insulin receptor catalyzes the tyrosine phosphorylation of caveolin-1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 30153-30158. 10.1074/jbc.M203375200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingler M., Erdélyi M., Szabad J. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1988). Function of torso in determining the terminal anlagen of the Drosophila embryo. Nature 335, 275-277. 10.1038/335275a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klueg K. M., Alvarado D., Muskavitch M. A. and Duffy J. B. (2002). Creation of a Gal4/UAS-coupled inducible gene expression system for use in Drosophila cultured cell lines. Genesis 34, 119-122. 10.1002/gene.10148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kockel L., Zeitlinger J., Staszewski L. M., Mlodzik M. and Bohmann D. (1997). Jun in Drosophila development: redundant and nonredundant functions and regulation by two MAPK signal transduction pathways. Genes Dev. 11, 1748-1758. 10.1101/gad.11.13.1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama Y. and Hu C.-D. (2010). An improved bimolecular flourescence complementation assay with a high signal-to-noise ratio. BioTechniques 49, 793-805. 10.2144/000113519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konogami T., Yang Y., Ogihara M. H., Hikiba J., Kataoka H. and Saito K. (2016). Ligand-dependent responses of the silkworm Prothoracicotropic Hormone receptor, Torso, are maintained by unusual intermolecular disulfide bridges in the transmembrane region. Sci. Rep. 6, 22437 10.1038/srep22437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon M. A. and Schlessinger J. (2010). Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 141, 1117-1134. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeMosy E. K. (2006). Spatially dependent activation of the patterning protease, Easter. FEBS. Letters 580, 2269-2272. 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Xia F. and Li W. X. (2003). Coactivation of STAT and Ras is required for germ cell proliferation and invasive migration in Drosophila. Dev . Cell. 5, 787-798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X. and Perrimon N. (1999). Dally cooperates with Drosophila Frizzled 2 to transduce Wingless signalling. Nature 400, 281-284. 10.1038/22343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Chou T. B., Williams N. G., Roberts T. and Perrimon N. (1993). Control of cell fate determination by p21ras/Ras1, an essential component of Torso signaling in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 7, 621-632. 10.1101/gad.7.4.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukoyanova N., Hoogenboom B. W. and Saibil H. R. (2016). The membrane attack complex, Perforin and cholesterol-dependent cytolysin superfamily of pore-forming proteins. J. Cell Sci. 129, 2125-2133. 10.1242/jcs.182741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J.-R., Raibaud A. and Ollo R. (1994). Terminal pattern elements in Drosophila embryo induced by the Torso-like protein. Nature 367, 741-745. 10.1038/367741a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni E. O., Desplan C. and Blau J. (2005). Circadian pacemaker neurons transmit and modulate visual information to control a rapid behavioral response. Neuron 45, 293-300. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBrayer Z., Ono H., Shimell M., Parvy J.-P., Beckstead R. B., Warren J. T., Thummel C. S., Dauphin-Villemant C. and Gilbert L. I. (2007). Prothoracicotropic Hormone regulates developmental timing and body size in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 13, 857-871. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald N. Q. and Hendrickson W. A. (1993). A structural superfamily of growth factors containing a cystine knot motif. Cell 73, 421-424. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90127-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineo A., Furriols M. and Casanova J. (2015). Accumulation of the Drosophila Torso-like protein at the blastoderm plasma membrane suggests that it translocates from the eggshell. Development 142, 1299-1304. 10.1242/dev.117630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S., Smolik S. M., Forte M. A. and Stork P. J. (2005). Ras-independent activation of ERK signaling via the torso receptor tyrosine kinase is mediated by Rap1. Curr. Biol. 15, 366-370. 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisato D. and Anderson K. V. (1994). The spätzle gene encodes a component of the extracellular signaling pathway establishing dorso-ventral pattern of the Drosophila embryo. Cell 76, 677-688. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90507-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nüsslein-Volhard C., Frohnhöfer H. G. and Lehmann R. (1987). Determination of anteroposterior polarity in Drosophila. Science 238, 1675-1681. 10.1126/science.3686007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nybakken K., Vokes S. A., Lin T.-Y., McMahon A. P. and Perrimon N. (2005). A genome-wide RNA interference screen in Drosophila melanogaster cells for new components of the Hh signaling pathway. Nat. Genet. 37, 1323-1332. 10.1038/ng1682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peverali F. A., Isaksson A., Patavassiliou A. G., Plastina P., Staszewski L. M., Mlodzik M. and Bohmann D. (1996). Phosphorylation of Drosophila Jun by the MAP kinase Rolled regulates photoreceptor differentiation. EMBO. J. 15, 3943-3950. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponting C. P. (1999). Chlamydial homologues of the MACPF (MAC/Perforin) domain. Curr. Biol. 9, R911-R913. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)80102-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rewitz K. F., Yamanaka N., Gilbert L. I. and O'Connor M. B. (2009). The insect neuropeptide PTTH activates receptor tyrosine kinase Torso to initiate metamorphosis. Science 326, 1403-1405. 10.1126/science.1176450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rørth P. (1998). Gal4 in the Drosophila germline. Mech. Dev. 78, 113-118. 10.1016/S0925-4773(98)00157-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybczynski R. (2005). Prothoracicotropic Hormone. In Comprehensive Molecular Insect Science, Vol. 3 (ed. Gilbert L.I., Iatrou K. and Gill S.), pp. 61-123. Oxford: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Saltiel A. R. and Pessin J. E. (2003). Insulin signaling in microdomains of the plasma membrane. Traffic 4, 711-716. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savant-Bhonsale S. and Montell D. J. (1993). Torso-like encodes the localized determinant of Drosophila terminal pattern formation. Genes Dev. 7, 2548-2555. 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider I. (1972). Cell lines derived from late embryonic stages of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 27, 353-365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider D. S., Jin Y., Morisato D. and Anderson K. V. (1994). A processed form of the Spätzle protein defines dorsal-ventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Development 120, 1243-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J. and Maruyama I. N. (2012). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor receptor TrkB exists as a preformed dimer in living cells. J. Mol. Signal. 7, 2 10.1186/1750-2187-7-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund T. and Korge K. (2001). Innervation of the ring gland of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Comp. Neurol. 431, 481-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims D., Duchek P. and Baum B. (2009). PDGF/VEGF signaling controls cell size in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 10, R20 10.1186/gb-2009-10-2-r20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1992). Torso receptor activity is regulated by a diffusible ligand produced at the extracellular terminal regions of the Drosophila egg. Cell 71, 987-1001. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90394-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprenger F., Stevens L. M. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1989). The Drosophila gene torso encodes a putative receptor tyrosine kinase. Nature 338, 478-483. 10.1038/338478a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein D. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1992). Multiple extracellular activities in Drosophila egg perivitelline fluid are required for establishment of embryonic dorsal-ventral polarity. Cell 68, 429-440. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90181-B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens L. M., Frohnhöfer H. G., Klingler M. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1990). Localized requirement for torso-like expression in follicle cells for development of terminal anlagen of the Drosophila embryo. Nature 346, 660-663. 10.1038/346660a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens L. M., Beuchle D., Jurcsak J., Tong L. and Stein D. (2003). The Drosophila embryonic patterning determinant Torsolike is a component of the eggshell. Curr. Biol. 13, 1058-1063. 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00379-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Johnston D. and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1992). The origin of pattern and polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell 68, 201-219. 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90466-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strålfors P. (2012). Caveolins and caveolae, roles in insulin signalling and diabetes. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 729, 111-126. 10.1007/978-1-4614-1222-9_8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P. D. and Davies D. R. (1995). The cystine-knot growth-factor superfamily. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 24, 269-292. 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.001413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R.-H. and Maruyama I. N. (2008). All EGF(Erb) receptors have preformed homo- and heterodimeric structures in living cells. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3207-3217. 10.1242/jcs.033399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich A. and Schlessinger J. (1990). Signal transduction by receptors with tyrosine kinase activity. Cell 61, 203-212. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90801-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward C. W., Lawrence M. C., Streitsov V. A., Adams T. E. and McKern N. M. (2007). The insulin and EGFR receptor structures: new insights into ligand-induced receptor activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 129-137. 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y., Yuan Q., Vogt N., Looger L. L., Jan L. Y. and Jan Y. N. (2010). Light-avoidance-mediating photoreceptors tile the Drosophila larval body wall. Nature 468, 921-926. 10.1038/nature09576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanaka N., Romero N. M., Martin F. A., Rewitz K. F., Sun M., O'Connor M. B. and Leopold P. (2013). Neuroendocrine control of Drosophila larval light preference. Science 341, 1113-1116. 10.1126/science.1241210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D. and Lin X. (2007). Drosophila glypican Dally-like acts in FGF-receiving cells to modulate FGF signaling during tracheal morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 312, 203-216. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan D., Wu Y., Yang Y., Belenkaya T. Y., Tang X. and Lin X. (2010). The cell-surface proteins Dally-like and Ihog differentially regulate Hedgehog signaling strength and range during development. Development 137, 2033-2044. 10.1242/dev.045740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa S.-i., Lee J.-S. and Ishimoto A. (1998). Identification and characterization of a novel line of Drosophila Schneider S2 cells that respond to wingless signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 32353-32359. 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]