Abstract

For the recently introduced isotropic-relaxed micromorphic generalized continuum model, we show that, under the assumption of positive-definite energy, planar harmonic waves have real velocity. We also obtain a necessary and sufficient condition for real wave velocity which is weaker than the positive definiteness of the energy. Connections to isotropic linear elasticity and micropolar elasticity are established. Notably, we show that strong ellipticity does not imply real wave velocity in micropolar elasticity, whereas it does in isotropic linear elasticity.

Keywords: ellipticity, positive definiteness, real wave velocity, rank-one convexity, acoustic tensor, relaxed micromorphic model

1. Introduction

Investigations of real wave propagation and ellipticity, in principle, are not new. Indeed, it is textbook knowledge for linear elasticity that positive definiteness of the elastic energy implies real wave velocities (phase velocities) where is the angular frequency and is the wavenumber of planar propagating waves. In classical elasticity, having real wave velocities is equivalent to rank-one convexity (strong ellipticity or Legendre–Hadamard ellipticity). Moreover, ellipticity is equivalent to the positive definiteness of the acoustic tensor. For anisotropic linear elasticity, see [1], whereas for anisotropic nonlinear elasticity we refer the reader to [2–5].

The same question of ellipticity and real wave velocities in generalized continuum mechanics has been discussed for micropolar models, e.g. in [6] and for elastic materials with voids in [7]. For the isotropic micromorphic model, results can be found with respect to positive-definite energy and/or real wave velocity in Nowacki [8], Smith [9], Mindlin [10, 11] and Eringen [12, pp. 277–280]. These latter results present conditions which are neither easily verifiable nor are truly transparent. This is due to the very high number of material coefficients of the Eringen–Mindlin theory that are strongly reduced in the relaxed micromorphic model [13]. Indeed, the implication that positive definiteness of the energy always implies real wave velocities is not directly established and demonstrated. In this paper, we investigate the relaxed micromorphic model in terms of conditions for real wave velocities for planar waves and establish a necessary and sufficient conditions for this to happen.

This paper is organized as follows. We shortly recall the basics of the relaxed micromorphic model and discuss the wave propagation problem for propagating planar waves. Because we deal with an isotropic model, we can, without loss of generality, assume wave propagation in one specific direction only. The dispersion relations are then obtained, and real wave velocities, under the assumption of uniform positiveness of the elastic energy, are established.

We next present a set of necessary and sufficient conditions for real wave velocities in the relaxed micromorphic model which is weaker than the positivity of the energy, as is the strong ellipticity condition with respect to positive definiteness of the energy in the case of linear elasticity. Then, for didactic purposes, we repeat the analysis for isotropic linear elasticity in order to see relations of our necessary and sufficient condition to the strong ellipticity condition in linear elasticity. Similarly, we discuss micropolar elasticity and establish the necessary and sufficient conditions for real wave propagation. We finally show that strong ellipticity in micropolar and micromorphic models is not sufficient for having real wave velocities, when dealing with plane waves.

2. The relaxed micromorphic model

The relaxed micromorphic model has been recently introduced into continuum mechanics in [14]. In subsequent works [15–18], the model has shown its wider applicability compared with the classical Mindlin–Eringen micromorphic model in diverse areas [10–12, 19].

The dynamic relaxed micromorphic model counts only eight constitutive parameters in the (simplified) isotropic case, namely five elastic moduli μe, λe, μmicro, λmicro, μc [Pa], one characteristic length Lc [m], the average macroscopic inertia ρ [kg] and the microinertia η [kg m−1]. The simplification consists of assuming one scalar microinertia parameter η and a uniconstant curvature expression. The characteristic length, Lc, is intrinsically related to non-local effects due to the fact that it weights a suitable combination of first-order space derivatives of the microdistortion tensor in the strain energy density (2.1). For a general presentation of the features of the relaxed micromorphic model in the anisotropic setting, we refer the reader to [20].

(a). Elastic energy density

The relaxed micromorphic model couples the macroscopic displacement , and an affine substructure deformation attached at each macroscopic point is encoded by the microdistortion field . Our novel relaxed micromorphic model endows the Mindlin–Eringen representation of linear micromorphic models with the second-order dislocation density tensor instead of the full gradient .1 In the isotropic hyperelastic case, the elastic energy density reads

| 2.1 |

where the parameters and the elastic stress are analogous to the standard Mindlin–Eringen micromorphic model. The model is well posed in the statical and dynamic case even for zero Cosserat couple modulus ; see [21, 22]. In that case, it is non-redundant in the sense of [23]. Well-posedness results for the statical and dynamic cases have been provided in [14], making decisive use of recently established new coercive inequalities, generalizing Korn's inequality to incompatible tensor fields [24–28].

Decisive for the relaxed micromorphic formulation is the definition of the elastic energy in terms of suitable strain tensors. Because is the macroscopic displacement gradient and P is the microdistortion, it appears possible to use the non-symmetric relative (elastic) strain tensor as the basic building block in the energy. Using the Cartan–Lie orthogonal decomposition, we may introduce

| 2.2 |

The microstructure contribution based on P alone is restricted, by infinitesimal frame indifference, to

| 2.3 |

Strict positive definiteness of the potential energy is equivalent to the following simple relations for the introduced parameters [14]:

| 2.4 |

As for the kinetic energy density, we consider that it takes the following (simplified) form:

| 2.5 |

where is the value of the averaged macroscopic mass density of the considered material, whereas is its microinertia density.

For very large sample sizes, a scaling argument shows easily that the relative characteristic length scale Lc of the micromorphic model must vanish. Therefore, we have a way of comparing a classical first-gradient formulation with the relaxed micromorphic model and to offer an a priori relation between the microscopic parameters on the one side, and the resulting macroscopic parameters on the other side [20, 29, 30]. We have

| 2.6 |

where are the moduli obtained for .

For future use, we define the elastic bulk modulus , the microscopic bulk modulus and the macroscopic bulk modulus , respectively,

| 2.7 |

In terms of these moduli, strict positive definiteness of the energy is equivalent to

| 2.8 |

If strict positive definiteness (2.8) holds, we can write the macroscopic consistency conditions as

| 2.9 |

and, again under condition (2.8),

| 2.10 |

Here, strict positivity (2.8) implies that

| 2.11 |

Because it is useful in what follows, we explicitly remark that

| 2.12 |

With these relations, it is easy to show how and imply . Moreover, as shown in appendix A (equations (A 2) and (A 3)), we note here that if only and , then the macroscopic parameters are less than or equal to respective microscopic parameters, namely

| 2.13 |

and, moreover, the following inequalities are satisfied:

| 2.14 |

Note that the Cosserat couple modulus μc [31] does not appear in the introduced scale between micro and macro.

(b). Dynamic formulation

The dynamic formulation is obtained by defining a joint Hamiltonian and assuming stationary action. The dynamic equilibrium equations are

| 2.15 |

We note here that the presence of the Curl P in the energy generates a non-local term Curl Curl P in the equation of motion, whereas the possibility of band gaps is still present; see [15]. The presence of the Curl P term is essential to simultaneously allow us to describe the non-localities and band gap in an enriched continuum mechanics framework.

Sufficiently far from a source, dynamic wave solutions may be treated as planar waves. Therefore, we now want to study harmonic solutions travelling in an infinite domain for the differential system (2.15). To do so, we define

| 2.16 |

and we introduce the unknown vectors

| 2.17 |

The definition of the unknown vectors was made considering the coupling of the variables in the equations of motion; see [15–18, 32–36]. More particularly, it has been shown in these previous works that three sets of equations can be isolated: one involving only longitudinal quantities, one involving only transverse quantities and one of three completely uncoupled equations. We suppose that the space dependences of all introduced kinematic fields are limited to a direction defined by a unit vector , which is the direction of propagation of the wave and which is assumed given. Hence, we look for solutions of (2.15) in the form

| 2.18 |

where , and are the unknown amplitudes of the considered waves, is the space of complex constant three-dimensional vectors,2 k is the wavenumber and ω is the wave frequency. Because our formulation is isotropic, we can, without loss of generality, specify the propagation direction . Then, , and we obtain that the space dependences of all introduced kinematic fields are limited to the component X, which is now the direction of propagation of the wave.3 This means that we look for solutions in the form

| 2.19 |

Replacing these expressions in equations (2.15), it is possible to express the system (see [15, 16]) as

| 2.20 |

with

| 2.21 |

| 2.22 |

and

| 2.23 |

Here, we have defined

Let us next define the diagonal matrix

| 2.24 |

Considering and the matrix , it is possible to formulate the problem (2.20) equivalently as4

| 2.25 |

Analogously considering

| 2.26 |

it is possible to obtain

| 2.27 |

In order to have non-trivial solutions of the algebraic systems (2.20), one must impose that

| 2.28 |

the solution of which allows us to determine the so-called dispersion relations for the longitudinal and transverse waves in the relaxed micromorphic continuum (figure 1).5 The solutions of the eigenvalue problem obtained via the proposed decomposition are the same as the ones obtained via the standard formulation shown in appendix Aa with the full matrix; for more details, see [34]. For estimates on the isotropic moduli, we refer the reader to [17, 33] and, for a comparison with other micromorphic models, to [32, 36]. For solutions of (2.28), we define

| 2.29 |

Real wavenumbers correspond to propagating waves, whereas complex values of k are associated with waves whose amplitude either grows or decays along the coordinate X. In linear elasticity, phase velocity and group velocity coincide, because there is no dispersion, and both are real; see section 3.

Because, in this paper, we are interested only in real k (outside the band-gap region), the wave velocity (phase velocity) is real, if and only if ω is real.

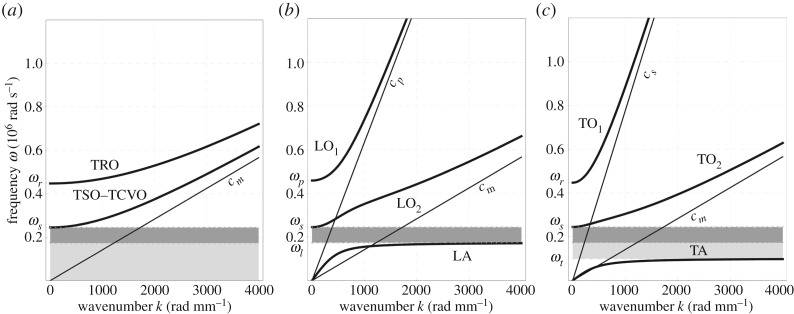

Figure 1.

Dispersion relations [17] for the relaxed micromorphic model with non-vanishing Cosserat couple modulus . Uncoupled waves (a), longitudinal waves (b) and transverse waves (c). TRO, transverse rotational optic; TSO, transverse shear optic; TCVO, transverse constant-volume optic; LA, longitudinal acoustic; LO1–LO2, first and second longitudinal optic; TA, transverse acoustic; TO1–TO2, first and second transverse optic. (a) ; (b) ; (c)

Because ω2 appears on the diagonal only, the problem (2.28) can be analogously expressed as an eigenvalue problem

| 2.30 |

where

| 2.31 |

| 2.32 |

| 2.33 |

Note that B1(k), B2(k), B3(k) and B4(k) are real symmetric matrices and, therefore, the resulting eigenvalues ω2 are real. Obtaining real wave velocities is tantamount to having for all solutions of (2.30).

(c). Necessary and sufficient conditions for real wave propagation

We show next that all the eigenvalues ω2 of B1(k), B2(k) and B3(k) are real and positive for every and non-negative for provided certain conditions on the material coefficients are satisfied. Sylvester's criterion states that a Hermitian matrix M is positive definite if and only if the leading principal minors are positive [38]. For the matrix , the three principal minors are

| 2.34 |

| 2.35 |

and

| 2.36 |

The three principal minors of are clearly positive for if6

| 2.37 |

Similarly, for the matrix , the three principal minors are

| 2.38 |

| 2.39 |

| 2.40 |

For the matrix , considering positive and separating terms in the brackets by looking at large and small values of k, we can state the necessary and sufficient conditions for strict positive definiteness of B2(k) at arbitrary ,

| 2.41 |

Because B4(k) is diagonal, it is easy to show that positive definiteness is tantamount to the set of necessary and sufficient conditions for

| 2.42 |

On the other hand, considering the case , we obtain that the matrices reduce to

| 2.43 |

Because the matrices are diagonal for , it is easy to show that positive semi-definiteness is tantamount to the set of necessary and sufficient conditions

| 2.44 |

Hence, we can state a simple sufficient condition for real wave velocities for all real k

| 2.45 |

In order to see a set of global necessary conditions for positivity at arbitrary we consider first large and small values of separately. For we must have

| 2.46 |

or analogously

| 2.47 |

while, for we must have

| 2.48 |

Because from (2.41) we have necessarily , , and from (2.44) we get , and considering together the two limits for k, we obtain the necessary condition

| 2.49 |

Inspection shows that (2.49) is our proposed sufficient condition (2.37). From and , it follows that . Therefore, condition (2.49) is necessary and sufficient. We have shown our main proposition as follows.

Proposition (real wave velocities). —

The dynamic relaxed micromorphic model (equation (2.15)) admits real planar waves if and only if

2.50

In (2.50), the requirement is redundant, because it is already assumed that . It is clear that positive definiteness of the elastic energy (2.4) implies (2.50). We remark that, as shown in appendix Aa, the set of inequalities (2.50) is already implied by

| 2.51 |

Finally letting and (or and .) generates the limit condition for real wave velocities ()

| 2.52 |

which coincides, up to μc, with the strong ellipticity condition in isotropic linear elasticity (see §3) and it coincides fully with the condition for real wave velocities in micropolar elasticity; see §4. A condition similar to (2.52) can be found in [10, equation 8.14 p. 26] where Mindlin requires that (in our notation),7 which are obtained from the requirement of positive group velocity at

| 2.53 |

Let us emphasize that our method is not easily generalized to two immediate extensions. First, one could be interested in the isotropic-relaxed micromorphic model with weighted inertia contributions and weighted curvatures [34]. Second, one could be interested in the anisotropic setting [20]. In the second case, the block structure of the problem will be lost, and one has to deal with the full case; see equation (A 23) in appendix A. Nonetheless, we expect positive definiteness to always imply real wave propagation.

In [34], we show that the tangents of the acoustic branches in in the dispersion curves are

| 2.54 |

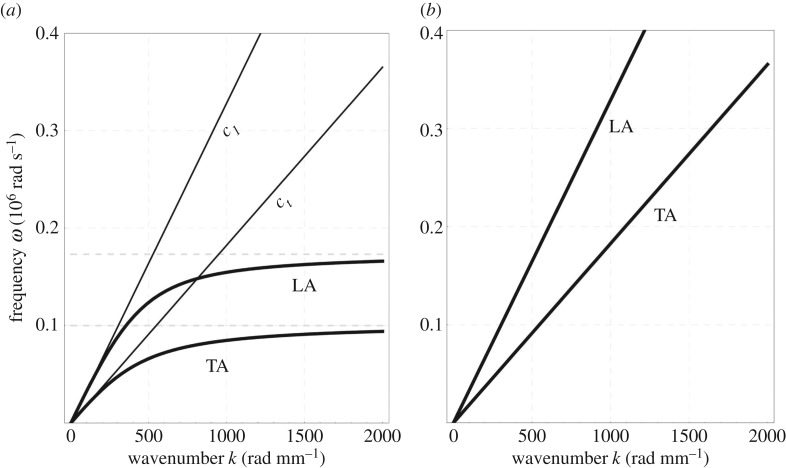

The tangents coincide with the classical linear elastic response if the latter has Lamé constants and , as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Dispersion relations for the longitudinal acoustic wave LA, and the transverse acoustic TA in the relaxed micromorphic model (a) and in a classical Cauchy medium (b).

3. A comparison: classical isotropic linear elasticity

For classical linear elasticity with isotropic energy density and kinetic energy density

| 3.1 |

The positive definiteness of the energy is equivalent to

| 3.2 |

It is easy to see that our homogenization formula (2.6) implies (3.2) under the condition of positive definiteness of the relaxed micromorphic model.

The dynamic formulation is obtained by defining a joint Hamiltonian and assuming stationary action. The dynamic equilibrium equations are

| 3.3 |

As before, in our study of wave propagation in micromorphic media, we limit ourselves to the case of plane waves travelling in an infinite domain. We suppose that the space dependence of all introduced kinematic fields is limited to a direction defined by a unit vector , which is the direction of propagation of the wave. Therefore, we look for solutions of (3.3) in the form

| 3.4 |

Because our formulation is isotropic, we can, without loss of generality, specify the direction . Then, , and we obtain

| 3.5 |

With this ansatz, it is possible to write (3.3) as

| 3.6 |

where

| 3.7 |

and

| 3.8 |

Here, we observe that is already diagonal and real. Requesting real wave velocities means . For , this leads to the classical so-called strong ellipticity condition

| 3.9 |

which is implied by positive definiteness of the energy (3.2).

In classical (linear or nonlinear) elasticity, the condition of real wave propagation (3.9) is equivalent to strong ellipticity and rank-one convexity. Indeed, rank-one convexity amounts to set ( with )

| 3.10 |

where is the fourth-order elasticity tensor. Condition (3.10) then reads

| 3.11 |

We may express (3.11) given as a quadratic form in , which results in

| 3.12 |

where the components of the symmetric and real matrix read

| 3.13 |

The three principal invariants are independent of the direction ξ owing to isotropy and are given by

| 3.14 |

Because is real and symmetric, its eigenvalues are real. The eigenvalues of the matrix are and (of multiplicity 2) such that positivity at is satisfied, if and only if8

| 3.15 |

which are the usual strong ellipticity conditions. We note here that the latter calculations also show that . Alternatively, one may directly form the so-called acoustic tensor by

| 3.16 |

in indices we have . With (3.16), we obtain9

| 3.17 |

and we see that strong ellipticity is equivalent to the positive definiteness of the acoustic tensor .

4. A further comparison: the linear Cosserat model

In the isotropic hyperelastic case, the elastic energy density and the kinetic energy density of the Cosserat model read

| 4.1 |

Introducing the canonical identification of with , A can be expressed as a function of as

| 4.2 |

Here, we assume for clarity a uniconstant curvature expression in terms of only . Strict positive definiteness of the potential energy is equivalent to the following simple relations for the introduced parameters:

| 4.3 |

The dynamic formulation is obtained by defining a joint Hamiltonian and assuming stationary action. The dynamic equilibrium equations are

| 4.4 |

see also [40–43] for formulations in terms of axial vectors. Note that, for zero Cosserat couple modulus the coupling of the two fields is absent, in opposition to the relaxed micromorphic model (equation (2.15)). Considering plane and stationary waves of amplitudes and , it is possible to express this system as

| 4.5 |

where

| 4.6 |

and

| 4.7 |

As done in the case of the relaxed micromorphic model, it is possible to express equivalently the problem with and the following symmetric matrix:

| 4.8 |

where

| 4.9 |

Because ω2 appears only on the diagonal, the problem can be analogously expressed as the following eigenvalue problems:

| 4.10 |

where

| 4.11 |

and

| 4.12 |

are the blocks of the acoustic tensor B

| 4.13 |

The eigenvalues of the matrix are simply the elements of the diagonal; therefore, we have

| 4.14 |

whereas for it is possible to find

| 4.15 |

where we have set

| 4.16 |

The acoustic branches are those curves as solutions of (4.9) that satisfy . We note here that the acoustic branches of the longitudinal and transverse dispersion curves have, as tangent in ,10

| 4.17 |

respectively. Moreover, the longitudinal acoustic branch is non-dispersive, i.e. a straight line with slope (4.17). The matrix is positive definite for arbitrary if

| 4.18 |

Using the Sylvester criterion, is positive definite, if and only if the principal minors are positive, namely

| 4.19 |

from which we obtain the condition

| 4.20 |

Considering these two sets of conditions, it is possible to state a necessary and sufficient condition for the positive definiteness of and and therefore of the acoustic tensor

| 4.21 |

which are implied by the positive definiteness of the energy (4.3). Eringen [12, p. 150] also obtains correctly (4.18) and (4.20) (in his notation ).

In [44, 45], strong ellipticity for the Cosserat micropolar model is defined and investigated. In this respect, we note that ellipticity is connected to acceleration waves, whereas our investigation concerns real wave velocities for planar waves. Similarly to [46], it is established in [44, 45] that strong ellipticity for the micropolar model holds if and only if (the uniconstant curvature case in our notation)

| 4.22 |

We conclude that, for micropolar material models (and therefore also for micromorphic materials), strong ellipticity (4.22) is too weak to ensure real planar waves because it is implied by, but does not imply, (4.21). This fact seems to have been appreciated also in the study of the Cosserat model [47–51].

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we derive the set of necessary and sufficient conditions that have to be imposed on the constitutive parameters of the relaxed micromorphic model in order to guarantee

— positive definiteness;

— real wave velocity; and

— Legendre–Hadamard strong ellipticity condition.

We show that if, on the one hand, definite positiveness implies real wave propagation, on the other hand, real wave propagation is not guaranteed by the strong ellipticity condition.

We conclude that in strong contrast to the case of classical isotropic linear elasticity, where the three concepts are known to be equivalent, in the case of the relaxed micromorphic continua only definite positiveness of the strain energy density can be considered to be a good criterion to guarantee real wave speeds in the considered media. The proposed considerations can be extended to all generalized continua where the equivalence between the three notions is far from being straightforward.

Acknowledgments

We thank Victor A. Eremeyev for helpful clarification.

Appendix A

(a) Inequality relations between material parameters

The formulae in §2a are based on the harmonic mean of two numbers and (or μe and μmicro). If the two numbers are positive, it is easy to see that

| A 1 |

Here, we show that the same conclusion still holds if we merely assume that . This allows for either or . Therefore, considering that , even if the energy is not strictly positive, it is possible to derive that

| A 2 |

Considering similarly , it is possible to obtain

| A 3 |

Therefore, if and , the macroscopic parameters are less than or equal to the respective microscopic parameters, namely

| A 4 |

and it is possible to show that

| A 5 |

Therefore, the set of inequalities (2.50) is implied from the smaller set

| A 6 |

We note here that because

| A 7 |

(b) The acoustic tensor for arbitrary direction

We suppose that the space dependence of all introduced kinematic fields is limited to a direction defined by a unit vector ξ, which is the direction of propagation of the wave. Therefore, we look for solutions of

| A 8 |

in the form

| A 9 |

where is the polarization vector and is the polarization matrix. We start by remarking that, considering , we have

| A 10 |

where is a linear operator with constant coefficients defined by the appropriate product rule of differentiation. Therefore, we obtain

| A 11 |

where

| A 12 |

The derivatives of can be evaluated by considering

| A 13 |

It can be noted that

| A 14 |

Therefore, it is possible to evaluate the as

| A 15 |

On the other hand, the second derivative of with respect to time is

| A 16 |

Analogously for u, it is possible to evaluate the gradient and the derivatives with respect to time as

| A 17 |

The sym, skew and tr of can then be expressed as

| A 18 |

Therefore, we have

| A 19 |

Here, we have considered that, given a generic and a scalar , we have

| A 20 |

With all the formulae obtained, it is possible to write (A 8) simplifying everywhere as

| A 21 |

or analogously

| A 22 |

At given , this is a linear system in which can be written in matrix format as

| A 23 |

Here, is the acoustic tensor. The columns of are

It is clear that, even with the aid of up-to-date computer algebra systems, it is practically impossible to determine the positive definiteness of the acoustic tensor as dependent on the given material parameters. In the main body of our paper, we succeed by choosing immediately the propagation direction and by considering a set of new variables (2.16). This allows us to obtain a certain pre-factorization of in blocks. Because the formulation is isotropic, choosing is no restriction, as argued before.

Footnotes

The dislocation tensor is defined as , where ϵ is the Levi–Civita tensor.

Here, we understand that, having found the (in general, complex) solutions of (2.19), only the real or imaginary parts separately constitute actual wave solutions which can be observed in reality.

In an isotropic model, it is clear that there is no direction dependence. More specifically, let us consider an arbitrary direction . Now we consider an orthogonal spatial coordinate change with . In the rotated variables, the ensuing system of PDEs (2.15) is form invariant; see [37].

It is possible to face the problem in two more equivalent ways. The first one is to consider from the start that the amplitudes of the microdistortion field are multiplied by the imaginary unit i, i.e. , as done in [10, p. 24, equation 8.6]. Doing so, we obtain a real matrix that can be symmetrized with . On the other hand, it is also possible to consider from the beginning , obtaining directly a real symmetric matrix.

The formal limit shows no dispersion at all giving two pseudo-acoustic linear curves, longitudinal and transverse with slopes and , respectively.

We note here that . Furthermore, if and , we have ; see appendix A.

Mindlin explains that such parameters ‘are less than those that would be calculated from the strain-stiffnesses [of the unit cell]. This phenomenon is due to the compliance of the unit cell and has been found in a theory of crystal lattices by Gazis & Wallis [39]’.

The eigenvalues of are independent of the propagation direction , which makes sense for the isotropic formulation at hand.

The term that in index notation reads is different from , i.e. .

To obtain the slopes in 0, it is possible to search for a solution of the type and then evaluate the limit for ; see [34] for a thorough explanation in the relaxed micromorphic case.

Author's contributions

All the authors contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Funding

The work of I.-D.G. was supported by a grant from the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research and Innovation, CNCSUEFISCDI, project no. PN-II-RU-TE-2014-4-1109. A.M. thanks INSA-Lyon for the funding of the BQR 2016 ‘Caractérisation mécanique inverse des métamatériaux: modélisation, identification expérimentale des paramètres et évolutions possibles’, as well as the PEPS CNRS-INSIS.

References

- 1.Chiriţă S, Danescu A, Ciarletta M. 2007. On the strong ellipticity of the anisotropic linearly elastic materials. J. Elast. 87, 1–27. (doi:10.1007/s10659-006-9096-7) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balzani D, Neff P, Schröder J, Holzapfel GA. 2006. A polyconvex framework for soft biological tissues. Adjustment to experimental data. Int. J. Solids Struct. 43, 6052–6070. (doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2005.07.048) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merodio J, Neff P. 2006. A note on tensile instabilities and loss of ellipticity for a fiber-reinforced nonlinearly elastic solid. Arch. Mech. 58, 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schröder J, Neff P. 2002. Application of polyconvex anisotropic free energies to soft tissues. In Proc. 5th World Congress on Computational Mechanics, Vienna, Austria, 7–12 July 2002. Barcelona, Spain: IACM.

- 5.Schröder J, Neff P, Ebbing V. 2008. Anisotropic polyconvex energies on the basis of crystallographic motivated structural tensors. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 56, 3486–3506. (doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2008.08.008) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith AC. 1967. Waves in micropolar elastic solids. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 5, 741–746. (doi:10.1016/0020-7225(67)90019-5) [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiriţă S, Ghiba I-D. 2009. Strong ellipticity and progressive waves in elastic materials with voids. Proc. R. Soc. A 466, 439–458. (doi:10.1098/rspa.2009.0360) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nowacki W. 1985. Theory of asymmetric elasticity. Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith AC. 1968. Inequalities between the constants of a linear micro-elastic solid. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 6, 65–74. (doi:10.1016/0020-7225(68)90020-7) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mindlin RD. 1963. Microstructure in linear elasticity. Technical report no. 50. Office of Naval Research, Arlington, VA, USA.

- 11.Mindlin RD. 1964. Micro-structure in linear elasticity. Arch. Ration. Mech. Anal. 16, 51–78. (doi:10.1007/BF00248490) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eringen AC. 1999. Microcontinuum field theories. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maugin GA. 2016. Non-classical continuum mechanics, vol. 51 Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neff P, Ghiba I-D, Madeo A, Placidi L, Rosi G. 2014. A unifying perspective: the relaxed linear micromorphic continuum. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 26, 639–681. (doi:10.1007/s00161-013-0322-9) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madeo A, Neff P, Ghiba I-D, Placidi L, Rosi G. 2014. Band gaps in the relaxed linear micromorphic continuum. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 95, 880–887. (doi:10.1002/zamm.201400036) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Madeo A, Neff P, Ghiba I-D, Placidi L, Rosi G. 2015. Wave propagation in relaxed micromorphic continua: modeling metamaterials with frequency band-gaps. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 27, 551–570. (doi:10.1007/s00161-013-0329-2) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madeo A, Barbagallo G, d'Agostino MV, Placidi L, Neff P. 2016. First evidence of non-locality in real band-gap metamaterials: determining parameters in the relaxed micromorphic model. Proc. R. Soc. A 472, 20160169 (doi:10.1098/rspa.2016.0169) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Madeo A, Neff P, Ghiba I-D, Rosi G. 2016. Reflection and transmission of elastic waves in non-local band-gap metamaterials: a comprehensive study via the relaxed micromorphic model. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 95, 441–479. (doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2016.05.003) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greene S, Gonella S, Liu WK. 2012. Microelastic wave field signatures and their implications for microstructure identification. Int. J. Solids Struct. 49, 3148–3157. (doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2012.06.011) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barbagallo G, d'Agostino MV, Abreu R, Ghiba I-D, Madeo A, Neff P. 2016 doi: 10.1098/rspa.2016.0790. Transparent anisotropy for the relaxed micromorphic model: macroscopic consistency conditions and long wave length asymptotics. ( http://arxiv.org/abs/1601.03667) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Neff P, Ghiba I-D, Lazar M, Madeo A. 2015. The relaxed linear micromorphic continuum: well-posedness of the static problem and relations to the gauge theory of dislocations. Q. J. Mech. Appl. Math. 68, 53–84. (doi:10.1093/qjmam/hbu027) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghiba I-D, Neff P, Madeo A, Placidi L, Rosi G. 2014. The relaxed linear micromorphic continuum: existence, uniqueness and continuous dependence in dynamics. Math. Mech. Solids 20, 1171–1197. (doi:10.1177/1081286513516972) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Romano G, Barretta R, Diaco M. 2016. Micromorphic continua: non-redundant formulations. Contin. Mech. Thermodyn. 28, 1659–1670. (doi:10.1007/s00161-016-0502-5) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neff P, Pauly D, Witsch K-J. 2015. Poincaré meets Korn via Maxwell: extending Korn's first inequality to incompatible tensor fields. J. Differ. Equ. 258, 1267–1302. (doi:10.1016/j.jde.2014.10.019) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neff P, Pauly D, Witsch K-J. 2012. Maxwell meets Korn: a new coercive inequality for tensor fields in with square-integrable exterior derivative. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 35, 65–71. (doi:10.1002/mma.1534) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Neff P, Pauly D, Witsch K-J. 2011. A canonical extension of Korn's first inequality to H(Curl) motivated by gradient plasticity with plastic spin. C. R. Math. 349, 1251–1254. (doi:10.1016/j.crma.2011.10.003) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer S, Neff P, Pauly D, Starke G. 2014. New Poincaré-type inequalities. C. R. Math. 352, 163–166. (doi:10.1016/j.crma.2013.11.017) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bauer S, Neff P, Pauly D, Starke G. 2016. Dev-Div- and DevSym-DevCurl-inequalities for incompatible square tensor fields with mixed boundary conditions. ESAIM 22, 112–133. (doi:10.1051/cocv/2014068) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neff P. 2004. On material constants for micromorphic continua. In Trends in Applications of Mathematics to Mechanics (eds Y Wang, K Hutter), pp. 337–348. Aachen, Germany: Shaker.

- 30.Neff P, Forest S. 2007. A geometrically exact micromorphic model for elastic metallic foams accounting for affine microstructure. Modelling, existence of minimizers, identification of moduli and computational results. J. Elast. 87, 239–276. (doi:10.1007/s10659-007-9106-4) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neff P. 2006. The Cosserat couple modulus for continuous solids is zero viz the linearized Cauchy-stress tensor is symmetric. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 86, 892–912. (doi:10.1002/zamm.200510281) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madeo A, Neff P, d'Agostino MV, Barbagallo G. 2016. Complete band gaps including non-local effects occur only in the relaxed micromorphic model. C. R. Mech. 344, 784–796. (doi:10.1016/j.crme.2016.07.002) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Madeo A, Collet M, Miniaci M, Billon K, Ouisse M, Neff P. 2016 Modeling real phononic crystals via the weighted relaxed micromorphic model with free and gradient micro-inertia. ( http://arxiv.org/abs/1610.03878)

- 34.d'Agostino MV, Barbagallo G, Ghiba I-D, Madeo A, Neff P. 2016 A panorama of dispersion curves for the weighted isotropic relaxed micromorphic model. ( http://arxiv.org/abs/ 1610.03296)

- 35.Madeo A, Neff P, Aifantis EC, Barbagallo G, d'Agostino MV. 2016 On the role of micro-inertia in enriched continuum mechanics. ( http://arxiv.org/abs/1607.07385)

- 36.Madeo A, Neff P, Barbagallo G, d'Agostino MV, Ghiba I-D. 2016 A review on wave propagation modeling in band-gap metamaterials via enriched continuum models. ( http://arxiv.org/abs/1609.01073)

- 37.Münch I, Neff P. 2016 Rotational invariance conditions in elasticity, gradient elasticity and its connection to isotropy. ( http://arxiv.org/abs/1603.06153)

- 38.Gilbert GT. 1991. Positive definite matrices and Sylvester's criterion. Am. Math. Month. 98, 44–46. (doi:10.2307/2324036) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gazis DC, Wallis RF. 1962. Extensional waves in cubic crystals plates. In Proc. 4th U.S. National Congress of Applied Mechanics, Berkeley, CA, 18–21 June, 1962, pp. 161–168. New York, NY: American Society of Mechanical Engineers.

- 40.Jeong J, Neff P. 2010. Existence, uniqueness and stability in linear Cosserat elasticity for weakest curvature conditions. Math. Mech. Solids 15, 78–95. (doi:10.1177/1081286508093581) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeong J, Ramézani H, Münch I, Neff P. 2009. A numerical study for linear isotropic Cosserat elasticity with conformally invariant curvature. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 89, 552–569. (doi:10.1002/zamm.200800218) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neff P, Jeong J. 2009. A new paradigm: the linear isotropic Cosserat model with conformally invariant curvature energy. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 89, 107–122. (doi:10.1002/zamm.200800156) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neff P, Jeong J, Fischle A. 2010. Stable identification of linear isotropic Cosserat parameters: bounded stiffness in bending and torsion implies conformal invariance of curvature. Acta Mech. 211, 237–249. (doi:10.1007/s00707-009-0230-z) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altenbach H, Eremeyev VA, Lebedev LP, Rendón LA. 2010. Acceleration waves and ellipticity in thermoelastic micropolar media. Arch. Appl. Mech. 80, 217–227. (doi:10.1007/s00419-009-0314-1) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eremeyev VA. 2005. Acceleration waves in micropolar elastic media. Doklady Phys. 50, 204–206. (doi:10.1134/1.1922562) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neff P. 2008 Relations of constants for isotropic linear Cosserat elasticity. Technical report, Fachbereich Mathematik, Technische Universituat Darmstadt, Darmstadt, Germany. See http://www.unidue.de/%7ehm0014/Cosserat_files/web_coss_relations.pdf (note: typographical errors in equations 2.8, 2.9, 2.10).

- 47.Bigoni D, Gourgiotis PA. 2016. Folding and faulting of an elastic continuum. Proc. R. Soc. A 472, 20160018 (doi:10.1098/rspa.2016.0018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gourgiotis PA, Bigoni D. 2016. Stress channelling in extreme couple-stress materials. Part I: strong ellipticity, wave propagation, ellipticity, and discontinuity relations. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 88, 150–168. (doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2015.09.006) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghiba I-D, Neff P, Madeo A, Münch I. 2016 A variant of the linear isotropic indeterminate couple-stress model with symmetric local force-stress, symmetric nonlocal force-stress, symmetric couple-stresses and orthogonal boundary conditions. Math. Mech. Solids. ()

- 50.Münch I, Neff P, Madeo A, Ghiba I-D. 2015 The modified indeterminate couple stress model: why Yang et al.'s arguments motivating a symmetric couple stress tensor contain a gap and why the couple stress tensor may be chosen symmetric nevertheless. ( http://arxiv.org/ abs/1512.02053)

- 51.Madeo A, Ghiba I-D, Neff P, Münch I. 2016. A new view on boundary conditions in the Grioli–Koiter–Mindlin–Toupin indeterminate couple stress model. Eur. J. Mech. A, Solids 59, 294–322. (doi:10.1016/j.euromechsol.2016.02.009) [Google Scholar]