Summary

Secreted factors are a key component of stem cell niche and their dysregulation compromises stem cell function. Legumain is a secreted cysteine protease involved in diverse biological processes. Here, we demonstrate that legumain regulates lineage commitment of human bone marrow stromal cells and that its expression level and cellular localization are altered in postmenopausal osteoporotic patients. As shown by genetic and pharmacological manipulation, legumain inhibited osteoblast (OB) differentiation and in vivo bone formation through degradation of the bone matrix protein fibronectin. In addition, genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition of legumain activity led to precocious OB differentiation and increased vertebral mineralization in zebrafish. Finally, we show that localized increased expression of legumain in bone marrow adipocytes was inversely correlated with adjacent trabecular bone mass in a cohort of patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Our data suggest that altered proteolytic activity of legumain in the bone microenvironment contributes to decreased bone mass in postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Keywords: legumain, bone marrow stromal cells, differentiation, proliferation, osteoblast, adipocyte, osteoporosis, mesenchymal stem cell, extracellular matrix, fibronectin

Highlights

-

•

Legumain determines differentiation fate of BMSCs in vitro and in vivo

-

•

Legumain regulates BMSC proliferation independent of its enzymatic activity

-

•

Inhibition of legumain leads to precocious bone formation in zebrafish

-

•

Legumain is overexpressed in bone marrow adipocytes of osteoporotic patients

Kassem and colleagues have investigated the role of legumain in cell fate decision of human bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs). Using multidisciplinary in vitro and in vivo approaches, they show that legumain functions as a novel “molecular switch” inhibiting osteoblast and enhancing adipocyte differentiation of BMSCs, through modulation of the ECM protein fibronectin, and that legumain expression is altered in the bone microenvironment of postmenopausal osteoporotic patients.

Introduction

Human bone marrow stromal cells (hBMSCs) are non-hematopoietic multipotent cells capable of differentiation into mesodermal cell types such as osteoblasts (OBs) and adipocytes (ADs) (Abdallah and Kassem, 2008). It is increasingly recognized that secreted factors have an important role in mediating hBMSC function to actively maintain homeostasis of skeletal tissue. In addition, secreted proteins mediate the observed therapeutic effects of hBMSCs on enhancing regeneration of skeletal (Hernigou et al., 2005), cardiac (Hare et al., 2009), dermal (Bey et al., 2010), and neural (Yamout et al., 2010) tissues. Characterizing the functions of proteins secreted by hBMSCs is a pre-requisite for understanding the mechanisms of their therapeutic effects and their role in tissue homeostasis in normal and disease states.

We recently reported a profile of hBMSC-secreted factors at different stages of ex vivo OB differentiation using a quantitative proteomic analysis based on stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (Kristensen et al., 2012). Among the differentially regulated proteins during OB differentiation, we identified legumain as a secreted protein that has not been previously implicated in hBMSC biology.

Legumain (also known as asparaginyl endopeptidase, AEP), encoded by the LGMN gene, is a broadly expressed lysosomal cysteine protease that is secreted as inactive prolegumain (56 kDa) and processed into enzymatically active 46 and 36 kDa forms, as well as a 17 kDa enzymatically inactive C-terminal fragment. Legumain directly regulates diverse physiological and pathological processes by remodeling tissue-specific targets (e.g., extracellular matrix [ECM] components, enzymes, receptors) (Chen et al., 2001, Clerin et al., 2008, Deryugina and Quigley, 2006, Ewald et al., 2008, Ewald et al., 2011, Liu et al., 2003, Manoury et al., 1998, Mattock et al., 2010, Miller et al., 2011, Morita et al., 2007, Papaspyridonos et al., 2006, Sepulveda et al., 2009, Solberg et al., 2015). In addition, legumain indirectly contributes to atherosclerotic plaque instability through activation of cathepsin L in the arterial ECM (Clerin et al., 2008, Kitamoto et al., 2007, Mattock et al., 2010, Papaspyridonos et al., 2006). Surprisingly, the non-enzymatic 17 kDa C-terminal fragment is also biologically active and inhibits osteoclast differentiation through binding to an uncharacterized receptor (Choi et al., 1999, Choi et al., 2001).

Here we report the role of legumain in regulating the differentiation fate of hBMSCs. Using cell-based and in vivo studies we show that legumain inhibited OB differentiation through degradation of fibronectin. During development, legumain-deficient zebrafish exhibited precocious bone formation and mineralization. Finally, abnormal expression and cellular localization of legumain was observed in bone biopsies obtained from patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Together, the present study reveals role of legumain in determining the differentiation fate of BMSCs thereby regulating bone formation.

Results

Legumain Expression and Activity Are Regulated during hBMSC Differentiation In Vitro and In Vivo

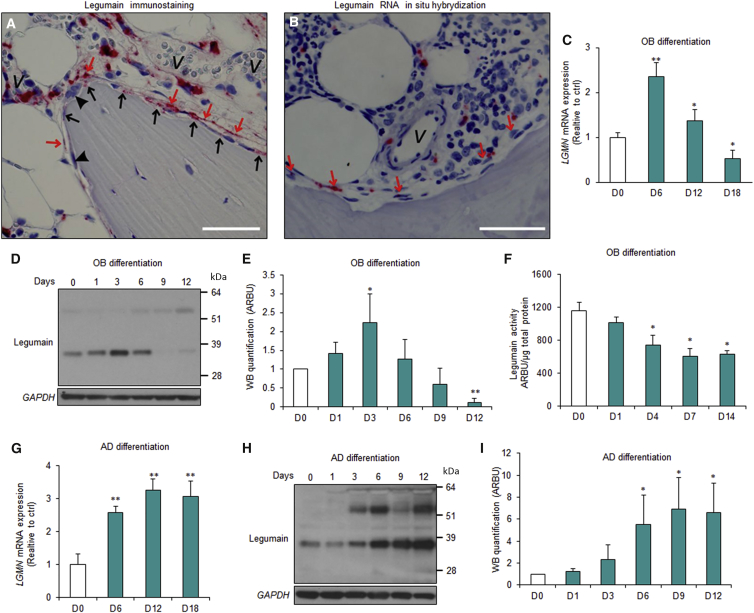

To assess cellular localization and regulation of legumain (LGMN) expression during OB differentiation under normal physiological conditions, we first performed histological analysis of adult human iliac crest bone biopsies. Legumain immunoreactivity was present in osteoprogenitors near bone-forming surfaces which included perivascular, canopy, and reversal cells (Figure 1A) (Delaisse, 2014, Kristensen et al., 2014). We did not detect immunoreactivity in mature OBs, osteocytes, or osteoclasts (Figure 1A). Legumain mRNA showed a similar expression pattern (Figure 1B). Next, we examined legumain expression and activity during ex vivo OB differentiation of hBMSCs. LGMN mRNA expression increased (Figure 1C) and the mature LGMN protein (36 kDa) accumulated (Figures 1D and 1E) during the early commitment phase (days 1–6) and were downregulated during the late maturation phase (days 6–18) of OB differentiation. Correspondingly, legumain enzymatic activity was reduced in differentiated OBs (Figure 1F). In contrast, LGMN mRNA expression and protein levels were increased during AD differentiation of hBMSCs (Figures 1G–1I).

Figure 1.

Regulation of Legumain Expression during In Vitro and In Vivo Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow Stromal Cells

(A and B) Immunohistochemical (A) and RNA in situ hybridization (B) analysis of legumain expression and localization in normal human iliac crest bone biopsies. n = 11 donors. Scale bar, 50 μm. Red arrows, canopy cells; black arrows, reversal cells; arrow heads, osteoclasts; v, vessel.

(C) qRT-PCR analysis of LGMN expression during osteoblast (OB) differentiation of hBMSCs at 6, 12, and 18 days (D6–D18) after start of differentiation (day 0, D0). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(D) Western blot analysis of legumain expression in cell lysates from hBMSC cultures during OB differentiation.

(E) Quantification of the mature legumain (36 kDa) band intensity. Arbitrary units (ARBU). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(F) Quantification of legumain activity in cell lysates from hBMSCs during OB differentiation. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(G) qRT-PCR analysis of LGMN expression during adipocyte (AD) differentiation of hBMSCs. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(H) Western blot analysis of legumain expression in cell lysates from hBMSC cultures during AD differentiation.

(I) Quantification of the mature legumain (36 kDa) band intensity. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

Legumain Deficiency Enhances OB Differentiation and Impairs AD Differentiation of hBMSCs

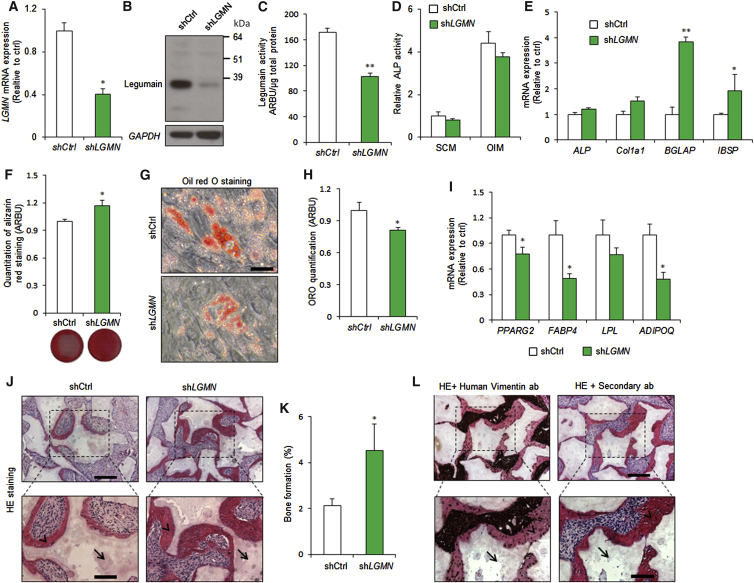

We employed lentiviral transduction to generate hBMSC lines with stable expression of LGMN shRNA (shLGMN) or a non-targeting control (shCtrl). shLGMN significantly reduced legumain mRNA, protein, and activity levels (Figures 2A–2C). In addition, LGMN knockdown reduced hBMSC proliferation (Figure S1A). After 6 days under osteogenic culture conditions, LGMN knockdown did not alter alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity (Figure 2D), or expression of the early OB commitment markers ALP and collagen 1 alpha 1 chain (Col1a1), but significantly upregulated the expression of the late OB maturation markers bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein (BGLAP) and integrin binding sialoprotein (IBSP) (Figure 2E). Moreover, LGMN knockdown enhanced the formation of mineralized ECM, as shown by the increased extent and intensity of alizarin red staining (Figure 2F). In contrast, LGMN knockdown inhibited AD differentiation (Figures 2G and 2H) and reduced expression of the AD maker genes: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2 (PPARG2), fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) and adiponectin, C1Q and collagen domain containing (ADIPOQ) (Figure 2I) under adipogenic culture conditions. To determine whether LGMN knockdown stimulated OB differentiation and bone-forming capacity in vivo, shLGMN or shCtrl cells were mixed with hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate granules as an osteoconductive carrier, and implanted subcutaneously in immune-deficient mice. Histological analysis of the implants after 8 weeks revealed a significant 2-fold increase in the amount of heterotopic bone formed by the shLGMN compared with the control (shCtrl) cells (Figures 2J and 2K). Human-specific vimentin staining showed that the heterotopic bone was generated by the transplanted hBMSCs (Figure 2L).

Figure 2.

Legumain Knockdown Enhanced Osteoblast Differentiation and In Vivo Bone Formation and Inhibited Adipocyte Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow Stromal Cells

hBMSCs were stably transfected with control (shCtrl) or LGMN shRNA (shLGMN).

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of LGMN expression. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(B) Western blot analysis of legumain and GAPDH control. Data represent three independent experiments.

(C) Quantification of legumain activity. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(D) Quantification of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity in the presence of standard culture medium (SCM) or osteoblast induction medium (OIM) (day 6). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. p > 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(E) qRT-PCR gene expression analysis of the early (ALP, Col1a1) and late (BGLAP, IBSP) OB marker genes. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(F) Quantification of alizarin red staining at day 12. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(G and H) Quantification of accumulated lipid droplets in the presence of AD induction medium using oil red O staining (day 12). Scale bar, 150 μm, Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(I) qRT-PCR gene expression analysis of the AD marker genes PPARG2, FABP4, LPL, and ADIPOQ. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(J) Histological analysis of in vivo bone formation by hBMSCs stably transfected with non-targeting control shRNA (shCtrl) or LGMN shRNA (shLGMN), 8 weeks after implantation in immune-deficient mice. Arrows, hydroxyapatite; arrow heads, bone. Scale bars: top panels, 500 μm; bottom panels, 250 μm.

(K) Quantification of the heterotopic bone formation, n = 4 implants for each cell type, Data represent mean ± SEM. ∗p ≤ 0.05, Mann-Whitney test.

(L) Human-specific vimentin staining of shLGMN implants. Arrows, hydroxyapatite; arrow heads, bone. Scale bars: top panels, 500 μm; bottom panels, 250 μm. ab, antibody.

See also Figure S1.

Pharmacological Inhibition of Legumain Activity Enhances OB Differentiation and Impairs AD Differentiation of hBMSCs

To determine whether legumain proteolytic activity is required for its effects on hBMSCs differentiation, we employed a small-molecule legumain inhibitor (SD-134) (Lee and Bogyo, 2012). hBMSC cultures incubated for 24 hr with SD-134 (50–500 nM) exhibited significant legumain inhibition (Figure S1B), but no effect on cell number was observed during 12 days treatment (Figure S1C). During in vitro OB differentiation of hBMSCs, SD-134 (50 nM) treatment did not induce significant changes in ALP activity (Figure S1D), but enhanced formation of mineralized matrix (Figure S1E). In contrast, SD-134 treatment inhibited AD differentiation (Figures S1F and S1G).

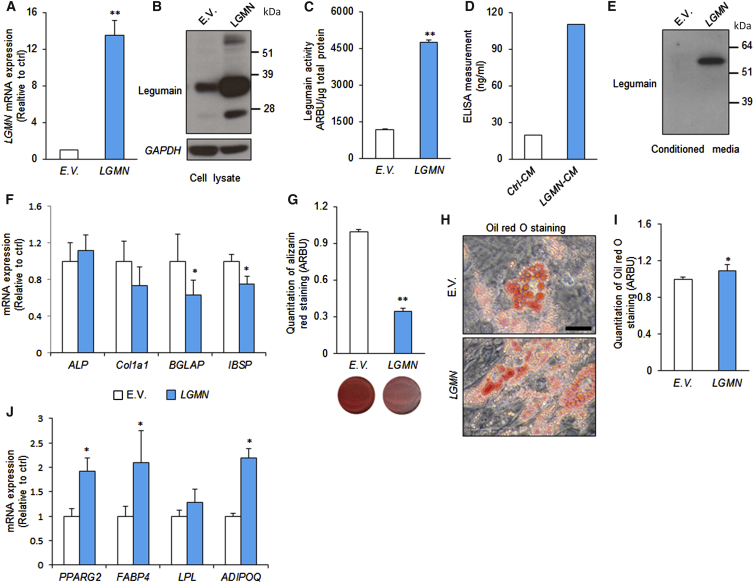

Overexpression of LGMN Impairs OB Maturation and Enhances AD Differentiation of hBMSCs

To determine whether increased LGMN activity actively blocks OB differentiation, we employed a retroviral transduction system to establish hBMSCs stably overexpressing full-length LGMN (hBMSC-LGMN) or an empty vector control (hBMSC-EV). LGMN overexpression was confirmed by mRNA, protein, and activity measurements (Figures 3A–3C). The levels of fully processed and activated legumain protein (36 kDa) were increased in lysates from hBMSC-LGMN cells (Figures 3B and 3C). In addition, secreted prolegumain (56 kDa) was detected in the conditioned media from hBMSC-LGMN cells (Figures 3D and 3E). In contrast to LGMN knockdown, hBMSC-LGMN exhibited increased cell proliferation (Figure S1H), impaired OB maturation, demonstrated by decreased late OB marker gene expression (BGLAP, IBSP), and decreased mineralized matrix formation, whereas expression of early OB commitment markers (ALP, Col1a1) was not altered by LGMN overexpression (Figures 3F and 3G). hBMSC-LGMN cells also exhibited enhanced AD differentiation (Figures 3H and 3I), and enhanced expression of AD marker genes (PPARG2, FABP4, and ADIPOQ) (Figure 3J). Thus, increased LGMN activity biases hBMSC differentiation to non-OB fates.

Figure 3.

Legumain Overexpression Inhibited Osteoblast and Enhanced Adipocyte Differentiation of Human Bone Marrow Stromal Cells

See also Figure S1.

(A–C) Legumain (LGMN)-transduced hBMSCs was established using a retroviral transduction system and the successful overexpression of legumain was confirmed using (A) qRT-PCR analysis of LGMN mRNA expression, (B) western blot analysis of legumain in cell lysate, and (C) quantification of legumain activity. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(D–G) Secretion of legumain in the conditioned medium (CM) was evaluated using (D) ELISA measurement (data represent mean from three technical replicates) and (E) western blot analysis of legumain in the CM from hBMSC-LGMN-overexpressing cell line (LGMN-CM) (data represent three independent experiments). To assess the effects of legumain on OB differentiation, control hBMSCs containing empty vector (E.V.) and hBMSC-LGMN cell lines were cultured in OB induction medium, and expressions of OB marker genes were analyzed using qRT-PCR (F) and mineralized matrix formation was determined by quantification of eluted alizarin red staining (G). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(H and I) To assess the effect of legumain on AD differentiation, control hBMSCs and hBMSC-LGMN cell lines were cultured in AD induction medium, and (H), (I) accumulation of lipid droplets was measured by quantification of the eluted oil red O staining, ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Scale bar, 150 μm.

(J) Expressions of AD marker genes were measured by qRT-PCR (day 7). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. E.V., empty vector; LGMN, legumain-overexpressing hBMSCs.

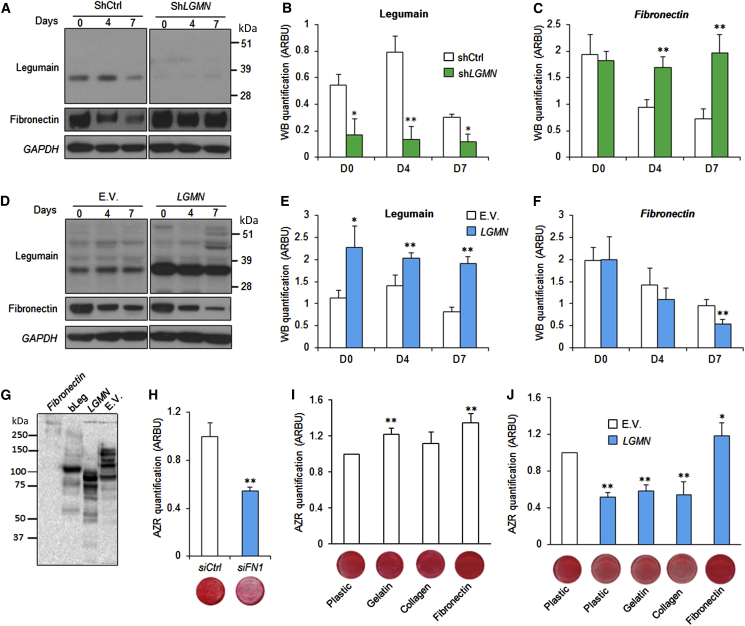

Legumain Degrades Fibronectin during hBMSC Differentiation

Since ECM proteins play an important role in OB differentiation (Hoshiba et al., 2012) and fibronectin functions as a master organizer of ECM biogenesis (Halper and Kjaer, 2014), we tested whether the effect of legumain on hBMSC differentiation is mediated through regulation of fibronectin levels. Lysates from legumain-deficient and legumain-overexpressing cells during in vitro OB differentiation showed an inverse relationship between the protein levels of mature legumain (36 kDa) and fibronectin (Figures 4A–4F). Fibronectin mRNA (FN1) levels did not change during OB differentiation (Figure S2A), which is consistent with post-transcriptional regulation. Incubation of purified human fibronctin with lysates from legumain-overexpressing HEK293 cells (Smith et al., 2012) confirmed that fibronectin is degraded by a legumain-dependent process in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure S2B). The fibronectin-degrading activity was also present in lysates from LGMN-overexpressing hBMSCs (Figure 4G). To determine whether intact fibronectin is required for OB differentiation, we blocked FN1 expression using siRNA, which inhibited OB maturation and formation of mineralized matrix (Figure 4H). To determine whether fibronectin degradation is sufficient to explain the inhibitory effects of legumain on OB maturation, we exposed osteogenic hBMSC cultures to a panel of purified ECM proteins (gelatin, collagen type 1, and fibronectin). Both gelatin and fibronectin enhanced the formation of mineralized matrix by control hBMSC (Figure 4I). However, only fibronectin blocked the inhibitory effect of legumain on OB differentiation and function (Figure 4J), suggesting that fibronectin is an endogenous legumain target.

Figure 4.

Legumain Degrades Fibronectin in Human Bone Marrow Stromal Cell cultures

(A) Western blot analysis of legumain and fibronectin in cell lysates of hBMSC lines with stable knockdown of legumain (shLGMN) during ex vivo OB differentiation (day 0–7).

(B and C) Quantification of protein band intensities in (A). ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(D) Western blot analysis of legumain and fibronectin in cell lysates of hBMSC lines with stable overexpression of legumain (LGMN) during ex vivo OB differentiation (day 0–7).

(E and F) Quantification of protein band intensities in (D). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(G) Western blot analysis of human fibronectin degradation by purified legumain from bovine kidneys (bLeg; 10:1 w/w; control) and the cell lysates from hBMSCs stably transfected with E.V. or legumain (LGMN; legumain overexpression).

(H) Quantitation of mineralized matrix formation on day 15 of OB differentiation, in the presence of siRNA against fibronectin (siFN) and non-targeting control siRNA (siCtrl). Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(I and J) Effect of different ECM proteins (gelatin, collagen 1, or fibronectin) on mineralized matrix formation by hBMSCs visualized by alizarin red staining and quantification. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p ≤ 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

See also Figure S2.

Legumain-Deficient Zebrafish Exhibit Precocious OB Differentiation and Bone Mineralization

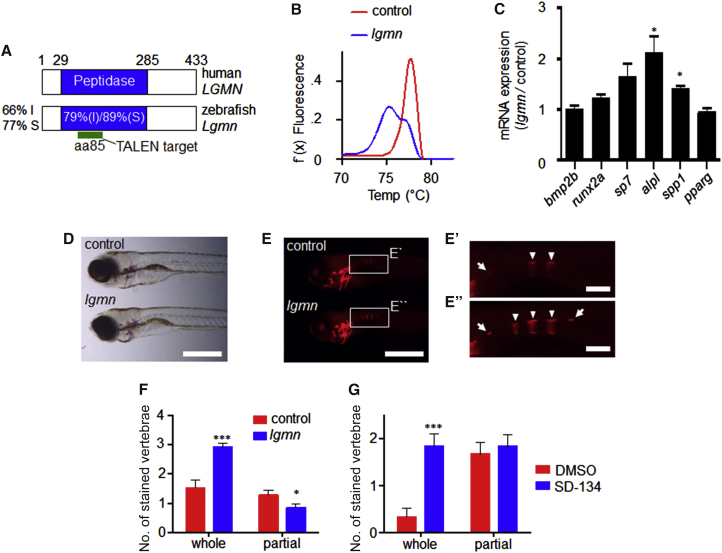

To examine the function of legumain during bone development, we targeted the essential peptidase domain within the zebrafish lgmn locus using transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) (Figure 5A). High-resolution melt analysis (HMRA) indicated that the lgmn gene was extensively modified in lgmn-TALEN-injected animals (Figure 5B). To quantify the extent of lgmn disruption, we used ON/OUT qPCR (Shah et al., 2015) and determined that ∼84% of lgmn alleles were modified. We proceeded to analyze OB differentiation and function in the lgmn-TALEN-injected animals compared with non-targeted control-injected animals. At 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) lgmn-deficient animals exhibited increased expression of genes associated with OB differentiation, including alkaline phosphatase (alp) and osteopontin (spp1), while the expression of the adipogenic marker PPAR-gamma (pparg) was unchanged (Figure 5C). By 7 dpf lgmn-deficient zebrafish did not show any gross morphological defects (Figure 5D). However, there were approximately twice as many mineralized vertebrae in lgmn-TALEN-injected animals compared with controls (Figures 5E and 5F). Next, we tested whether post-embryonic OB progenitors remained sensitive to legumain activity. Zebrafish embryogenesis is complete by 3 dpf (Kimmel et al., 1995). Therefore, we treated animals from 3 to 7 dpf with the legumain inhibitor SD-134. Consistent with the osteogenic effect of genetic lgmn disruption, SD-134-treated zebrafish exhibited an increase in the number of mineralized vertebrae at 7 dpf (Figure 5G).

Figure 5.

Legumain Inhibits OB Differentiation and Bone Mineralization In Vivo

(A) Conservation of zebrafish lgmn. I, amino acid identity; S, amino acid similarity.

(B) High-resolution melting analysis of pooled lgmn-TALEN and control-injected animals at 3 days post-fertilization (dpf).

(C) qRT-PCR analysis of OB and AD marker genes at 5 dpf. Data represent mean ± SEM of three pools of ten animals. ∗p ≤ 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(D and E) Control and lgmn mutant animals at 7 dpf. Scale bars, 500 μM. (D) Bright field and (E) fluorescent alizarin red staining. (E′ and E″) Higher-magnification images of boxed regions. Arrowheads, whole vertebrae stained; arrows, partial vertebrae stained. Scale bars, 100 μM.

(F) Number of alizarin-red-stained vertebrae in lgmn and control animals at 7 dpf. Data represent mean ± SEM, n > 30 for each group. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.005 two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(G) Animals were treated with SD-134 (500 μM) or 1% DMSO from 3 to 7 dpf. Number of alizarin-red-stained vertebrae at 7 dpf. Data represent mean ± SEM, n = 12 for each group. ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.005 two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

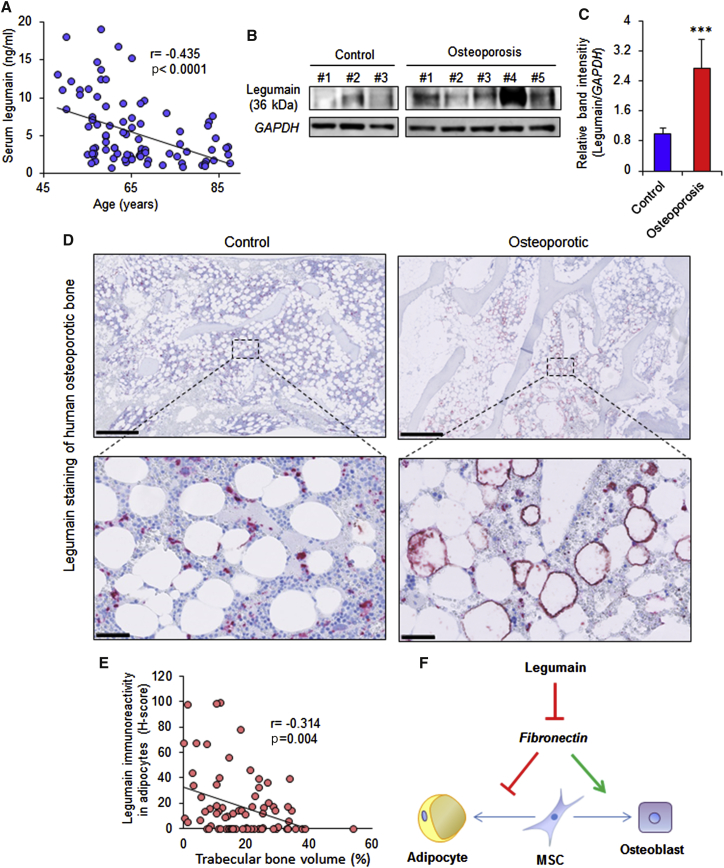

Legumain Serum Levels Decrease with Aging, and Local Expression of Legumain Is Increased in the Bone Microenvironment of Osteoporotic Patients

Legumain has recently been identified as a biomarker for diverse pathological states (Ashley et al., 2016, Guo et al., 2013, Lin et al., 2014, Lunde et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2012, Wu et al., 2014). We examined serum levels of legumain in 89 women aged 48–87 years and found an inverse relationship between serum legumain levels and age (Figure 6A). To determine legumain-localized activity within the bone microenvironment, we established primary hBMSC cultures from iliac crest bone marrow aspirates. Legumain levels were significantly higher in osteoporotic patients compared with age-matched controls (Figures 6B and 6C). In addition, immunohistochemical analyses of bone biopsies from postmenopausal osteoporotic patients (n = 13) and age-matched controls (n = 11) revealed legumain overexpression in bone marrow ADs in most osteoporotic samples (8 out of 13) (Figure 6D). To determine whether legumain-overexpressing ADs affected adjacent bone formation, we measured the trabecular bone volume in 80 random regions of interest (ROI = 1 mm2) in osteoporotic bone biopsies. Regions with legumain-positive ADs exhibited significantly reduced trabecular bone volume and there was an inverse relationship between legumain immunoreactivity in ADs and the local trabecular bone volume (Spearman r = −0.314, p = 0.004) (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

Effect of Aging and Osteoporosis on Legumain Protein Levels in Human Serum and Bone Microenvironment

(A) Serum legumain levels in 89 women, aged 48–87 years, p < 0.0001 using Spearman correlation analysis.

(B) Western blot analysis of mature legumain (36 kDa) and GAPDH in cell lysates from primary hBMSC cultures established from bone marrow aspirates of osteoporotic patients (n = 5) and age-matched controls (n = 3).

(C) Quantification of western blot band intensities normalized to GAPDH. Data represent mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.005, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test.

(D) Upper panel: legumain staining of bone biopsies from postmenopausal osteoporotic patients (n = 11) and age-matched control individuals (n = 13). Scale bars, 1 mm. Lower panel: higher-magnification images of the boxed regions. Scale bars, 50 μm.

(E) Correlation of trabecular bone area with legumain expression by adipocytes in biopsies from postmenopausal osteoporotic patients (n = 80 random regions of interest [ROI] = 1 mm2), p = 0.004 using Spearman correlation analysis.

(F) Proposed mode-of-action of legumain for regulation of hBMSC lineage commitment.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate a physiological role of legumain in regulating bone formation and possibly bone mass, as well as a role in the pathophysiology of reduced bone mass observed in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis. In particular, we find that legumain functions in the bone-remodeling microenvironment to inhibit OB differentiation and to enhance AD differentiation of hBMSCs, through regulation of ECM fibronectin deposition.

Our studies demonstrate that legumain inhibits late stages of ex vivo OB differentiation and the formation of mineralized ECM, suggesting that legumain regulates the ECM-hBMSC interaction that is required for the expression of the mature OB phenotype (Mathews et al., 2012). We identified fibronectin degradation as a mediator of legumain effects, similar to its role in renal proximal tubular cells, which is required for normal renal function (Morita et al., 2007). Fibronectin is known to enhance OB differentiation through interaction with the α5β1 integrin receptor and is required for OB maturation, survival, and matrix mineralization (Brunner et al., 2011, Linsley et al., 2013, Mathews et al., 2012, Moursi et al., 1997). In contrast, fibronectin exerts inhibitory effects on lipid accumulation and AD differentiation (Antras et al., 1989, Rodriguez Fernandez and Ben-Ze'ev, 1989, Spiegelman and Ginty, 1983).

Our data suggest that the proteolytic activity of legumain is important for its effects on hBMSC differentiation and bone formation. Legumain has been reported to regulate bone resorption through inhibition of osteoclast formation and function by its C-terminal fragment (17 kDa), which is enzymatically inactive, suggesting that legumain exerts protease-independent functions (Choi et al., 1999). In addition, legumain exhibits carboxypeptidase (Dall and Brandstetter, 2013) and peptide ligase activity (Dall et al., 2015). The possible involvement of these actions of legumain in regulating skeletal homeostasis requires further studies.

We observed that genetic loss- and gain-of-function of legumain were associated with changes in BMSC proliferation. However, regulation of BMSC proliferation by legumain is independent of its enzymatic activity, since small-molecule inhibition of legumain activity did not alter BMSC proliferation. This observation corroborates previous reports showing regulation of cell proliferation by legumain, independent of its enzymatic activity (Andrade et al., 2011). Further support of the potential role of legumain in osteoprogenitor cell proliferation is based on its colocalization with the proliferating osteoblastic cells in human bone biopsies. The proliferation status of osteoprogenitor cells near the bone-forming surfaces, as determined by immunohistochemical analysis of Ki-67, has been previously reported in human bone specimens (Kristensen et al., 2014). Interestingly, the pattern of Ki-67 immunoreactivity coincided with legumain expression, as the legumain-positive osteoprogenitor cells (such as canopy cells) are also Ki-67 positive, whereas the mature osteoblastic cells (such as bone-lining cells) are both legumain negative and Ki-67 negative.

We employed the zebrafish model to investigate the developmental and pharmacological effects of legumain inhibition in vivo. Zebrafish is an attractive model for in vivo screening studies, due to the molecular and cellular conservation of skeletal development and its predictive value when studying human diseases (Fisher et al., 2003, Grimes et al., 2016, Hayes et al., 2014, Li et al., 2009). For example, mutations in zebrafish collagen type IA1 reproduce many aspects of osteogenesis imperfecta (Fisher et al., 2003), and ptk7 mutant zebrafish have been identified as suitable models for scoliosis (Grimes et al., 2016). We extend the usefulness of this model by showing that late developmental events such as the mineralization of vertebrae are amenable to analysis in TALEN-injected animals. Our finding that legumain-deficient zebrafish exhibit enhanced OB differentiation and bone mineralization is consistent with the in vitro effects of legumain knockdown. In addition, we show that post-embryonic pharmacological inhibition of legumain recapitulates the osteogenic effects of genetic legumain ablation.

The serum levels of legumain decreased with aging, which was counterintuitive in relation to the proposed function of legumain in bone. However, the major tissue source(s) of serum legumain are not known and the decline in serum levels of legumain with aging may be connected to age-related decrease in renal function that may influence both clearance and production of legumain (the kidneys could be a major source of circulating legumain, but this is not clear at the moment). Thus, direct examination of legumain within the bone microenvironment is required for understanding its biological role in skeletal homeostasis.

Osteoporosis is a systemic bone disease, characterized by decreased bone formation, reduced bone mass, and disruption of normal bone architecture, resulting in bone fragility and increased risk of fractures (Compston, 2010). Legumain expression was elevated in hBMSCs from osteoporotic patients and, at single-cell resolution, legumain overexpression in ADs inversely correlated with local trabecular bone volume. Bioinformatic analysis revealed the presence of NF-κB binding sites in the legumain promoter, suggesting that the proinflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α and IL6), known to be upregulated in osteoporotic bone marrow microenvironment (Charatcharoenwitthaya et al., 2007), could regulate legumain expression.

In summary, our findings identified legumain as a “molecular switch” with opposing effects on bone and fat formation by hBMSCs through degradation of the ECM protein fibronectin (Figure 6F) and that altered expression of legumain in the bone microenvironment contributes to the pathophysiology of trabecular bone loss in osteoporosis. Finally, our data suggest that inhibition of legumain activity would be a promising approach to enhance bone regeneration.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culturing, Differentiation, and siRNA Transfection

We have employed our well-characterized hBMSC-TERT cell line (as a model of hBMSC) established by ectopic expression of the catalytic subunit of human telomerase, as described previously (Abdallah et al., 2005, Simonsen et al., 2002). Primary hBMSC cultures were established from bone marrow aspirates of osteoporotic patients and age-matched control subjects, as described before (Lee et al., 2004). Informed consent was obtained from all donors and the study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Region of Southern Denmark (issue no. 2003-41-3206, 2008-00-92). Cells were cultured in standard culture medium (SCM) containing minimal essential medium (MEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (Gibco) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All employed cell types were regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Cell culture plates were coated with collagen type 1 (6 μg/cm2; Sigma), gelatin (1 μg/cm2; Sigma), or fibronectin (1 μg/cm2; Sigma) and incubated at room temperature for 1 hr. The solution was then removed and the plates were air dried for 45 min, rinsed with PBS (without Ca2+ or Mg2+) followed by seeding cells.

For OB differentiation, 20 × 103 cells/cm2 were seeded and induced with OB induction medium (OIM) containing 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (Calbiochem), 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma), 50 μg/ml L-ascorbic acid (Wako Pure Chemicals Industries), 10 nM 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (LEO Pharma) in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. The medium was changed every third day. Control cells were cultured in SCM. Quantification of ALP activity and alizarin red staining were performed as described previously (Jafari et al., 2015).

For AD differentiation, cells were plated at a density of 35 × 103 cells/cm2 and induced with adipogenic induction medium containing 10% horse serum (Gibco), 100 nM dexamethasone (Sigma), 500 nM insulin (Sigma), 1 μM BRL49653 (Sigma), and 0.25 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (Sigma) in MEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% P/S. The medium was changed every third day. Control cells were cultured in SCM. Oil red O staining of the accumulated lipid droplets in mature ADs was performed as described previously (Jafari et al., 2015).

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection was carried out as described previously (Jafari et al., 2015). In brief, Lipofectamine 2000 was used as transfection reagent and a reverse-transfection protocol was employed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen) and OB differentiation was induced 48 hr after siRNA transfection. Non-targeting no. 1 siRNA (Ambion) and siRNA against fibronectin (sense: GGCUCAGCAAAUGGUUCAGtt) (Ambion) were used at 25 nM (Hammond and Kruger, 1988) (Schuck et al., 2004).

Legumain Activity Assay

Cells were washed with PBS and lysed using lysis buffer containing 1 mM disodium EDTA, 100 mM sodium citrate, 1% n-octyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (pH 5.8). The total protein concentration in the lysates was measured using Bradford assay (Hammond and Kruger, 1988). To measure legumain activity, 10 μg total protein in a total volume of 20 μL was added to 100 μL of assay buffer (39.5 mM citric acid, 121 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM Na2EDTA, 0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate, and 1 mM DTT) in a dark 96-well plate, followed by adding 50 μL of peptide substrate (Z-Ala-Ala-Asn-AMC; 10 μM final concentration) (Bachem) in assay buffer as described previously (Johansen et al., 1999). The plate was then incubated at 30°C for 1 hr and the fluorescent intensity (380EX/460EM) was measured using a FLUOstar Omega multimode microplate reader.

Heterotopic Bone Formation Assay In Vivo

To evaluate the in vivo bone formation, 5 × 105 cells of either shLGMN or shCtrl cell lines were loaded on scaffolds containing 40 mg hydroxyapatite/tricalcium phosphate ceramic powder (Zimmer Scandinavia), incubated at 37°C overnight, and implanted subcutaneously on the dorsal side of 8-week-old female non-obese diabetic.CB17-Prkdcscid/J mice as described previously (Abdallah et al., 2008). A simple randomization method was used to assign mice to different groups. After 8 weeks, implants (n = 4 implants/cell line) were retrieved and fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 24 hr, decalcified in formic acid for 3 days, and embedded in paraffin. sections (4 μm, n = 9/implant) were cut and stained with H&E(Bie & Berntsen). Bone volume per total volume was blindly quantified using pixel scoring method as described previously (Abdallah et al., 2008). Human-specific vimentin staining (Thermo Scientific, RM-9120) was used to show that the bone formed in the implants was of human origin. Mice experiments were carried out in accordance with permissions issued by the Danish Animal Experiments Inspectorate (2012-DY-2934-00006).

Zebrafish Studies

Zebrafish (Danio rerio) were housed at 28°C, in a 14 hr light and 10 hr dark cycle. Embryos were collected by natural spawning and raised at 28°C in E3 solution according to standard protocols (Westerfield, 2007). A pair of TALENs recognizing exon 4 of the zebrafish lgmn gene were constructed by the platinum gate method (Sakuma et al., 2013). lgmn_TAL1: NN-NG-NN-NG-NG-NG-NI-NN-NG-NI-NI-HD-HD-HD-NG-NI-HD. lgmn_TAL2: HD-HD-NI-NG-NG-NG-NN-NN-NG-HD-NG-NN-NG-NG. TALEN mRNA was synthesized by in vitro transcription using the T7 mMESSAGE mMACHINE Kit (Ambion). mRNA (125 pg) encoding each TALEN heterodimer was injected into the cytoplasm of the cell of one-cell-stage wild-type zebrafish embryos. Control injections used lgmn_TAL1 and an irrelevant TAL2. TALEN efficiency was monitored by HRMA using KAPA-HRM master mix (Kapa Biosystems) on an Eco Real-Time PCR machine (Illumina). HRMA_F: 5′-TGA TTT GTC AGT TCT TGC TCC TT-3′. HRMA_R: 5′-ACT TAC GTC CCC AAT GTA GTC C-3′. ON/OUT PCR was performed as described using HRMA_F + HRMA_R as outer primers and HRMA_F + lgmn_ON: 5′-CCA TTT GGT CTG TTT ATG ACC ACT-3′ for “ON” PCR (Shah et al., 2015). Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and the aqueous phase was isolated by column purification (Zymo Research). qRT-PCR was performed using a KAPA One-Step Universal Master Mix (KAPA Biosystems) on an Eco Real-Time PCR machine (Illumina) using the ΔΔCT method. Table S3 shows the primers used for qRT-PCR. Alizarin red staining and blind quantifications of the vertebrae were performed as described previously (Westerfield, 2007) and imaged with a Leica M165 FC microscope. SD-134 was added to E3 medium at 500 μM in 1% DMSO from 3 to 7 dpf. Simple randomization was used to assign the fish to SD-134 or DMSO groups. The use and treatment of zebrafish in this project were in accordance with and approved by the Animal Ethics Review Committee, Garvan Institute of Medical Research.

Immunohistochemical Analyses of Human Bone Specimens

Bone biopsy specimens from 13 postmenopausal osteoporotic patients (mean age, 77 years; range, 68–86 years) and 11 age-matched controls (mean age, 75 years; range, 67–83 years) were included in the study (Kristensen et al., 2014). In accordance with approval from the Danish National Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (journal no S-2007.01.21), formal consent was not required for the controls, whose biopsies were included in the study retrospectively; oral and written informed content was obtained from the osteoporotic donors included in the study. Sections (3.5-μm thick) from the decalcified paraffin-embedded bone specimens from postmenopausal osteoporotic patients and controls were immunostained with mouse anti-legumain (1:400, Santa Cruz, SC-133234, clone B-8) antibodies, which were labeled with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG polymers (1:10; DPVM110HRP, BrightVision). The signal was amplified with digoxigen-conjugated peroxidase-reactive tyramide (1:900; NEL748B001KT, Perkin-Elmer), labeled with alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated sheep anti-digoxigen (1:500; 11093274910, Roche), and visualized with Liquid Permanent Red (DAKO). The stained sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin and mounted with Aqua-Mount. The semi-quantitative analyses estimated the prevalence of cells with either weak (+1), moderate (+2), or strong (+3) staining within the different cell populations. We employed systematic random analysis for selection of visual fields following the central axis in the biopsies. The H score (range, 0–300) was calculated using the previously published equation (Andersen et al., 2013, Detre et al., 1995). H score = ∑Pi × i, where i is the staining intensity (0–3) and Pi is the percentage of cells stained with each intensity (0%–100%).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad) or Microsoft Excel 2010. Data are represented as mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments, unless otherwise stated. Normal distribution of the data was tested using the D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus normality test. Testing for statistical differences between variables was carried out using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test on the normally distributed data. Statistical differences between variables that did not follow normal distribution were determined using the Mann-Whitney test. Linear regression analysis and the Spearman correlation coefficient (r) were employed for the correlation analyses. p ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author Contributions

A.J., D.Q., T.L.A., Y.Z., B.P., S.P., L.C., and N.D., performed the experiments. T.L.A., S.K., J.M.D., and P.K.A. collected human samples. A.J., D.Q., B.M.A., H.T.J., D.H., R.S., and M.K. wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. A.J., D.Q., T.L.A., S.K., H.T.J., J.M.D., B.M.A., D.H., R.S., and M.K., contributed to the conceptual idea, the experimental design of the study, and editing of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Henrik Daa Schrøder, Department of Pathology, University of Southern Denmark, for providing bone sections for initial evaluation of legumain expression and help with staining interpretation and Dr. Charles Edward Frary for collecting human bone marrow samples. The SD-134 legumain inhibitor was kindly provided by Dr. Matt Bogyo, Stanford University, California, USA. The excellent technical assistance of Bianca Jørgensen, Vivianne Joosten, Lone Christiansen, Hilde Nilsen, Kaja Rau Laursen, and Birgit MacDonald is highly appreciated. D.Q. received a fellowship from the Ministry of Higher Education, Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). The project received support from the Nordisk Research Committee, Novo Nordisk Foundation (projects 10309 and 16284), the Lundbeck Foundation (R77-A7208), and the Region of Southern Denmark, University of Oslo and Anders Jahres Foundation for the Promotion of Science (to R.S.), and NHRMC, and NIH AG027065 (to S.K.).

Published: February 2, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, two figures, and three tables and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.stemcr.2017.01.003.

Supplemental Information

References

- Abdallah B.M., Kassem M. Human mesenchymal stem cells: from basic biology to clinical applications. Gene Ther. 2008;15:109–116. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah B.M., Haack-Sorensen M., Burns J.S., Elsnab B., Jakob F., Hokland P., Kassem M. Maintenance of differentiation potential of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells immortalized by human telomerase reverse transcriptase gene despite [corrected] extensive proliferation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;326:527–538. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdallah B.M., Ditzel N., Kassem M. Assessment of bone formation capacity using in vivo transplantation assays: procedure and tissue analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;455:89–100. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-104-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen T.L., Abdelgawad M.E., Kristensen H.B., Hauge E.M., Rolighed L., Bollerslev J., Kjaersgaard-Andersen P., Delaisse J.M. Understanding coupling between bone resorption and formation: are reversal cells the missing link? Am. J. Pathol. 2013;183:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade V., Guerra M., Jardim C., Melo F., Silva W., Ortega J.M., Robert M., Nathanson M.H., Leite F. Nucleoplasmic calcium regulates cell proliferation through legumain. J. Hepatol. 2011;55:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antras J., Hilliou F., Redziniak G., Pairault J. Decreased biosynthesis of actin and cellular fibronectin during adipose conversion of 3T3-F442A cells. Reorganization of the cytoarchitecture and extracellular matrix fibronectin. Biol. Cell. 1989;66:247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley S.L., Xia M., Murray S., O'Dwyer D.N., Grant E., White E.S., Flaherty K.R., Martinez F.J., Moore B.B. Six-SOMAmer index relating to immune, protease and angiogenic functions predicts progression in IPF. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159878. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey E., Prat M., Duhamel P., Benderitter M., Brachet M., Trompier F., Battaglini P., Ernou I., Boutin L., Gourven M. Emerging therapy for improving wound repair of severe radiation burns using local bone marrow-derived stem cell administrations. Wound Repair Regen. 2010;18:50–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner M., Millon-Fremillon A., Chevalier G., Nakchbandi I.A., Mosher D., Block M.R., Albiges-Rizo C., Bouvard D. Osteoblast mineralization requires beta1 integrin/ICAP-1-dependent fibronectin deposition. J. Cell Biol. 2011;194:307–322. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charatcharoenwitthaya N., Khosla S., Atkinson E.J., McCready L.K., Riggs B.L. Effect of blockade of TNF-alpha and interleukin-1 action on bone resorption in early postmenopausal women. J. Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:724–729. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.M., Fortunato M., Stevens R.A., Barrett A.J. Activation of progelatinase A by mammalian legumain, a recently discovered cysteine proteinase. Biol. Chem. 2001;382:777–783. doi: 10.1515/BC.2001.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.J., Reddy S.V., Devlin R.D., Menaa C., Chung H., Boyce B.F., Roodman G.D. Identification of human asparaginyl endopeptidase (legumain) as an inhibitor of osteoclast formation and bone resorption. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:27747–27753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.J., Kurihara N., Oba Y., Roodman G.D. Osteoclast inhibitory peptide 2 inhibits osteoclast formation via its C-terminal fragment. J. Bone Miner Res. 2001;16:1804–1811. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2001.16.10.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerin V., Shih H.H., Deng N., Hebert G., Resmini C., Shields K.M., Feldman J.L., Winkler A., Albert L., Maganti V. Expression of the cysteine protease legumain in vascular lesions and functional implications in atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2008;201:53–66. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compston J. Osteoporosis: social and economic impact. Radiol. Clin. North Am. 2010;48:477–482. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2010.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall E., Brandstetter H. Mechanistic and structural studies on legumain explain its zymogenicity, distinct activation pathways, and regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:10940–10945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall E., Fegg J.C., Briza P., Brandstetter H. Structure and mechanism of an aspartimide-dependent peptide ligase in human legumain. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015;54:2917–2921. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaisse J.M. The reversal phase of the bone-remodeling cycle: cellular prerequisites for coupling resorption and formation. Bonekey Rep. 2014;3:561. doi: 10.1038/bonekey.2014.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deryugina E.I., Quigley J.P. Matrix metalloproteinases and tumor metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:9–34. doi: 10.1007/s10555-006-7886-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detre S., Saclani Jotti G., Dowsett M. A “quickscore” method for immunohistochemical semiquantitation: validation for oestrogen receptor in breast carcinomas. J. Clin. Pathol. 1995;48:876–878. doi: 10.1136/jcp.48.9.876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald S.E., Lee B.L., Lau L., Wickliffe K.E., Shi G.P., Chapman H.A., Barton G.M. The ectodomain of Toll-like receptor 9 is cleaved to generate a functional receptor. Nature. 2008;456:658–662. doi: 10.1038/nature07405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald S.E., Engel A., Lee J., Wang M., Bogyo M., Barton G.M. Nucleic acid recognition by Toll-like receptors is coupled to stepwise processing by cathepsins and asparagine endopeptidase. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:643–651. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher S., Jagadeeswaran P., Halpern M.E. Radiographic analysis of zebrafish skeletal defects. Dev. Biol. 2003;264:64–76. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes D.T., Boswell C.W., Morante N.F., Henkelman R.M., Burdine R.D., Ciruna B. Zebrafish models of idiopathic scoliosis link cerebrospinal fluid flow defects to spine curvature. Science. 2016;352:1341–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P., Zhu Z., Sun Z., Wang Z., Zheng X., Xu H. Expression of legumain correlates with prognosis and metastasis in gastric carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halper J., Kjaer M. Basic components of connective tissues and extracellular matrix: elastin, fibrillin, fibulins, fibrinogen, fibronectin, laminin, tenascins and thrombospondins. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014;802:31–47. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-7893-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond J.B., Kruger N.J. The Bradford method for protein quantitation. Methods Mol. Biol. 1988;3:25–32. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-126-8:25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare J.M., Traverse J.H., Henry T.D., Dib N., Strumpf R.K., Schulman S.P., Gerstenblith G., DeMaria A.N., Denktas A.E., Gammon R.S. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of intravenous adult human mesenchymal stem cells (prochymal) after acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;54:2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes M., Gao X., Yu L.X., Paria N., Henkelman R.M., Wise C.A., Ciruna B. ptk7 mutant zebrafish models of congenital and idiopathic scoliosis implicate dysregulated Wnt signalling in disease. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4777. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernigou P., Poignard A., Beaujean F., Rouard H. Percutaneous autologous bone-marrow grafting for nonunions. Influence of the number and concentration of progenitor cells. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2005;87:1430–1437. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiba T., Kawazoe N., Chen G. The balance of osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation in human mesenchymal stem cells by matrices that mimic stepwise tissue development. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2025–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari A., Siersbaek M.S., Chen L., Qanie D., Zaher W., Abdallah B.M., Kassem M. Pharmacological inhibition of protein kinase G1 enhances bone formation by human skeletal stem cells through activation of RhoA-Akt signaling. Stem Cells. 2015;33:2219–2231. doi: 10.1002/stem.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen H.T., Knight C.G., Barrett A.J. Colorimetric and fluorimetric microplate assays for legumain and a staining reaction for detection of the enzyme after electrophoresis. Anal. Biochem. 1999;273:278–283. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel C.B., Ballard W.W., Kimmel S.R., Ullmann B., Schilling T.F. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto S., Sukhova G.K., Sun J., Yang M., Libby P., Love V., Duramad P., Sun C., Zhang Y., Yang X. Cathepsin L deficiency reduces diet-induced atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-knockout mice. Circulation. 2007;115:2065–2075. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.688523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen L.P., Chen L., Nielsen M.O., Qanie D.W., Kratchmarova I., Kassem M., Andersen J.S. Temporal profiling and pulsed SILAC labeling identify novel secreted proteins during ex vivo osteoblast differentiation of human stromal stem cells. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11:989–1007. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.012138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen H.B., Andersen T.L., Marcussen N., Rolighed L., Delaisse J.M. Osteoblast recruitment routes in human cancellous bone remodeling. Am. J. Pathol. 2014;184:778–789. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Bogyo M. Synthesis and evaluation of aza-peptidyl inhibitors of the lysosomal asparaginyl endopeptidase, legumain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:1340–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R.H., Kim B., Choi I., Kim H., Choi H.S., Suh K., Bae Y.C., Jung J.S. Characterization and expression analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from human bone marrow and adipose tissue. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2004;14:311–324. doi: 10.1159/000080341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Felber K., Elks P., Croucher P., Roehl H.H. Tracking gene expression during zebrafish osteoblast differentiation. Dev. Dyn. 2009;238:459–466. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Qiu Y., Xu C., Liu Q., Peng B., Kaufmann G.F., Chen X., Lan B., Wei C., Lu D. Functional role of asparaginyl endopeptidase ubiquitination by TRAF6 in tumor invasion and metastasis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju012. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsley C., Wu B., Tawil B. The effect of fibrinogen, collagen type I, and fibronectin on mesenchymal stem cell growth and differentiation into osteoblasts. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2013;19:1416–1423. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2012.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Sun C., Huang H., Janda K., Edgington T. Overexpression of legumain in tumors is significant for invasion/metastasis and a candidate enzymatic target for prodrug therapy. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2957–2964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunde N.N., Holm S., Dahl T.B., Elyouncha I., Sporsheim B., Gregersen I., Abbas A., Skjelland M., Espevik T., Solberg R. Increased levels of legumain in plasma and plaques from patients with carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manoury B., Hewitt E.W., Morrice N., Dando P.M., Barrett A.J., Watts C. An asparaginyl endopeptidase processes a microbial antigen for class II MHC presentation. Nature. 1998;396:695–699. doi: 10.1038/25379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews S., Bhonde R., Gupta P.K., Totey S. Extracellular matrix protein mediated regulation of the osteoblast differentiation of bone marrow derived human mesenchymal stem cells. Differentiation. 2012;84:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattock K.L., Gough P.J., Humphries J., Burnand K., Patel L., Suckling K.E., Cuello F., Watts C., Gautel M., Avkiran M. Legumain and cathepsin-L expression in human unstable carotid plaque. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller G., Matthews S.P., Reinheckel T., Fleming S., Watts C. Asparagine endopeptidase is required for normal kidney physiology and homeostasis. FASEB J. 2011;25:1606–1617. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-172312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita Y., Araki H., Sugimoto T., Takeuchi K., Yamane T., Maeda T., Yamamoto Y., Nishi K., Asano M., Shirahama-Noda K. Legumain/asparaginyl endopeptidase controls extracellular matrix remodeling through the degradation of fibronectin in mouse renal proximal tubular cells. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1417–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moursi A.M., Globus R.K., Damsky C.H. Interactions between integrin receptors and fibronectin are required for calvarial osteoblast differentiation in vitro. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110:2187–2196. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.18.2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaspyridonos M., Smith A., Burnand K.G., Taylor P., Padayachee S., Suckling K.E., James C.H., Greaves D.R., Patel L. Novel candidate genes in unstable areas of human atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2006;26:1837–1844. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000229695.68416.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Fernandez J.L., Ben-Ze'ev A. Regulation of fibronectin, integrin and cytoskeleton expression in differentiating adipocytes: inhibition by extracellular matrix and polylysine. Differentiation. 1989;42:65–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1989.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma T., Ochiai H., Kaneko T., Mashimo T., Tokumasu D., Sakane Y., Suzuki K., Miyamoto T., Sakamoto N., Matsuura S. Repeating pattern of non-RVD variations in DNA-binding modules enhances TALEN activity. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:3379. doi: 10.1038/srep03379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck S., Manninen A., Honsho M., Fullekrug J., Simons K. Generation of single and double knockdowns in polarized epithelial cells by retrovirus-mediated RNA interference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4912–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401285101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda F.E., Maschalidi S., Colisson R., Heslop L., Ghirelli C., Sakka E., Lennon-Dumenil A.M., Amigorena S., Cabanie L., Manoury B. Critical role for asparagine endopeptidase in endocytic Toll-like receptor signaling in dendritic cells. Immunity. 2009;31:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A.N., Davey C.F., Whitebirch A.C., Miller A.C., Moens C.B. Rapid reverse genetic screening using CRISPR in zebrafish. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:535–540. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen J.L., Rosada C., Serakinci N., Justesen J., Stenderup K., Rattan S.I., Jensen T.G., Kassem M. Telomerase expression extends the proliferative life-span and maintains the osteogenic potential of human bone marrow stromal cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2002;20:592–596. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R., Johansen H.T., Nilsen H., Haugen M.H., Pettersen S.J., Maelandsmo G.M., Abrahamson M., Solberg R. Intra- and extracellular regulation of activity and processing of legumain by cystatin E/M. Biochimie. 2012;94:2590–2599. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solberg R., Smith R., Almlof M., Tewolde E., Nilsen H., Johansen H.T. Legumain expression, activity and secretion are increased during monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation and inhibited by atorvastatin. Biol. Chem. 2015;396:71–80. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2014-0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelman B.M., Ginty C.A. Fibronectin modulation of cell shape and lipogenic gene expression in 3T3-adipocytes. Cell. 1983;35:657–666. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Chen S., Zhang M., Li N., Chen Y., Su W., Liu Y., Lu D., Li S., Yang Y. Legumain: a biomarker for diagnosis and prognosis of human ovarian cancer. J. Cell Biochem. 2012;113:2679–2686. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. University of Oregon Press; 2007. The Zebrafish Book: A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) [Google Scholar]

- Wu M., Shao G.R., Zhang F.X., Wu W.X., Xu P., Ruan Z.M. Legumain protein as a potential predictive biomarker for Asian patients with breast carcinoma. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2014;15:10773–10777. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.24.10773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamout B., Hourani R., Salti H., Barada W., El-Hajj T., Al-Kutoubi A., Herlopian A., Baz E.K., Mahfouz R., Khalil-Hamdan R. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in patients with multiple sclerosis: a pilot study. J. Neuroimmunol. 2010;227:185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.