Abstract

Metastatic nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a debilitating and deadly disease with virtually no chance for long-term survival. Chemotherapy has improved both survival and quality of life for patients with advanced disease. Overall survival of patients with metastatic NSCLC has gradually increased from 8 to 12 months over the past three decades with the introduction of new chemotherapeutic drugs and agents directed at novel targets in the cancer cell. Epidermal growth factor receptor and vascular endothelial growth factor are two such targets. Recent developments also include treatment based on histology and the use of maintenance therapy. It has been recognized that lung cancer is a very complex disease. It is common practice to include a number of scientific correlative studies in the design of clinical trials in order to determine predictive markers of benefit from treatment. This article will review the current approach to the treatment of advanced NSCLC including the use of chemotherapy and molecularly targeted agents. Future directions including the use of potentially predictive biomarkers and innovative clinical trials aimed at a more individualized approach to treatment will also be discussed.

Keywords: lung cancer, chemotherapy, targeted treatment

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths for both men and women in the United States with an estimated 219 440 new cases and 159 390 deaths in 2009.1 Unfortunately, 40% of lung cancer patients have distant metastases at the time of diagnosis. Long-term survival is still dismal with only 15% of all patients surviving 5 years.

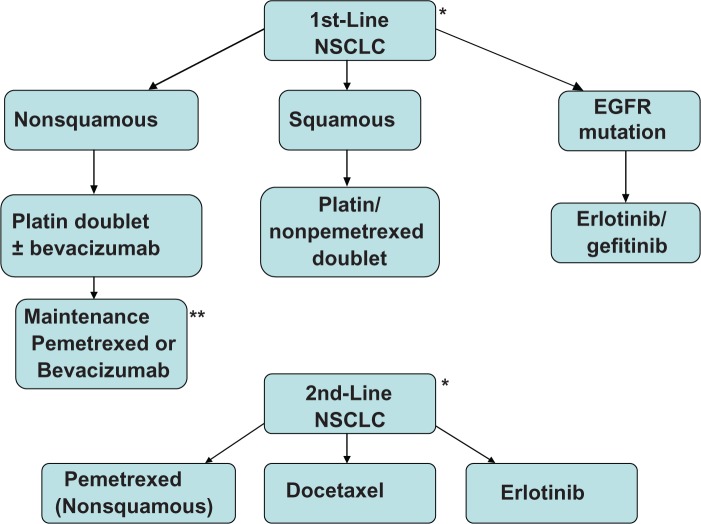

Lung cancer is generally divided into two histologic categories: nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) representing approximately 85% of the cases while small cell lung cancer, which has been declining in incidence, comprises the remainder of the patients. In the past two decades a number of chemotherapeutic drugs including vinorelbine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, gemcitabine, and pemetrexed have been approved for use in the treatment of NSCLC.2–6 Novel agents targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have now an established role in the treatment of this disease. There are a number of new targeted agents that are currently being developed and evaluated in NSCLC. This article will review the standard of care for the management of advanced NSCLC and will discuss future treatment strategies. See Figure 1 for a pictorial summary of the treatment of advanced NSCLC.

Figure 1.

Treatment of advanced NSCLC.

Notes: *Clinical trials when available should always be considered. **Maintenance therapy should be considered on an individual patient basis.

Abbreviation: NSCLC, nonsmall cell lung cancer.

Systemic chemotherapy

It has clearly been established that treatment of advanced NSCLC with chemotherapy improves overall survival (OS) compared to best supportive care alone.7,8 A meta-analysis published in the British Medical Journal in 1995 evaluating trials comparing supportive care with supportive care plus chemotherapy, determined that there was a 27% reduction in relative risk of death and a 10% absolute improvement in survival at one year for patients treated with chemotherapy.8 It has been shown that combination chemotherapy not only increases survival but does so without compromising the patient’s quality of life (QOL).7 Based on this information, systemic chemotherapy has an established role in the treatment of advanced NSCLC.

Importance of histology

Previous major clinical trials have included all the histologies of NSCLC and, interestingly, most of them reported equal efficacy regardless of the histologic subtypes. There have been new developments with regard to differential treatment benefit by histology that will be discussed in the next section.

Accurate identification of the histologic classification of NSCLC is dependent on sufficient tissue and the skill of the pathologist. Fine needle aspirate (FNA), which is the diagnostic procedure most often used in the metastatic setting, may not provide adequate tissue for evaluation. For this reason, a core biopsy specimen is preferred over FNA. One retrospective study examined the accuracy of histologic diagnoses obtained by bronchoscopy.9 The cases were limited only to bronchoscopically visible endobronchial or submucosal lesions. The combination of forceps biopsy, brushings, and washings was unable to provide histologic diagnosis in 30% of NSCLC patients even in this highly selected population. Another retrospective analysis compared preoperative histologic/cytologic diagnosis with postsurgical diagnosis in 170 patients with NSCLC.10 Forty-nine percent of the preoperative diagnoses were made using only a cytology specimen and in 47% of the specimens the subtype of NSCLC could not be determined. In another study, the differentiation of adenocarcinoma from squamous cell carcinoma utilizing cytologic specimens was correct in 60% of cases. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for TTF-1, CK7, CK 20, and P63 improved the accuracy.11

In general, pathologists can often distinguish between small cell and nonsmall cell cancers but interpathologist disagreement often occurs in subtyping NSCLC.12,13 A study recently reported attempts to evaluate concordance among pathologists with regard to subclassification of NSCLC histologic types.13 There was more agreement among expert lung pathologists than community pathologists and when the tumors were more differentiated in appearance. If histologic diagnosis is uncertain. IHC staining for tumors markers may be helpful, as well as obtaining a second opinion from another pathologist with expertise in lung pathology.

First-line chemotherapy for advanced NSCLC

Platinum-based doublet chemotherapy is considered the standard first-line treatment for NSCLC patients with a good performance status (PS). Doublet chemotherapy improves response rate (RR) and one-year survival when compared to single agent treatment even when third generation drugs (eg, vinorelbine, taxanes, gemcitabine) are used.14

Platinum remains the fundamental backbone of doublet chemotherapy. The results from Phase III trials comparing various platinum-based combinations indicated that there was no one regimen that emerged as superior. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 1594 compared 3 platinum/third generation combinations to cisplatin and paclitaxel (24 hour infusion).15 The median survival (MS) was 8 months and the one-year survival was 33% for all 4 study arms. TAX 326 was another large Phase III trial that randomized patients to receive cisplatin/vinorelbine or docetaxel combined with either cisplatin or carboplatin.4 Survival outcomes were better for cisplatin/docetaxel when compared to the control arm, cisplatin/vinorelbine. There was no significant difference between the control and carboplatin/docetaxel groups. Table 1 summarizes some of the major Phase III randomized trials comparing the various doublet regimens. The inter-trial differences in RR and survival are likely due to variations among study populations (ie, fraction of stages IIIB/IV, inclusion of PS 2 patients, etc) and variations in treatment upon disease progression.

Table 1.

Phase III randomized trials of platin-based doublets

| Reference | Patients | Treatment | RR (%) | OS (mo) | 1 Year (%) | P (OS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelly16 | 408 | VNR/CDDP | 28 | 8.1 | 36 | |

| CBDCA/PAC | 25 | 8.6 | 38 | 0.87 | ||

| Rosell17 | 618 | PAC/CDDP | 28 | 9.8 | 38 | |

| PAC/CBDCA | 25 | 8.2 | 33 | 0.019 | ||

| Scagliotti18 | 612 | GEM/CDDP | 30 | 9.8 | 37 | |

| CBDCA/PAC | 32 | 9.9 | 43 | 0.484a | ||

| VNR/CDDP | 30 | 9.5 | 37 | 0.105a | ||

| Ohe19 | 602 | CDDP/CPT-11 | 31 | 13.9 | 59.2 | |

| CBDCA/PAC | 32.4 | 12.3 | 51 | 0.465 | ||

| CDDP/GEM | 30.1 | 14 | 59.6 | 0.949 | ||

| CDDP/VNR | 33.1 | 11.4 | 48.3 | 0.242 | ||

| Schiller15 | 1207 | PAC/CDDP | 21 | 7.8 | 31 | |

| GEM/CDDP | 22 | 8.1 | 36 | NSb | ||

| DOC/CDDP | 17 | 7.4 | 31 | NS | ||

| CBDCA/PAC | 17 | 8.1 | 34 | NS | ||

| Fossella4 | 1218 | VNR/CDDP | 24.5 | 10.1 | 41 | |

| DOC/CDDP | 31.6 | 11.3 | 46 | 0.044 | ||

| VNR/CDDP | 24.5 | 9.9 | 40 | |||

| DOC/CBDCA | 23.9 | 9.4 | 38 | 0.657 |

Notes: If more than two regimens were compared in one study, the topmost regimen was the reference regimen and P value is based on comparison to the reference regimen.

P value for 1-year survival rate.

P value was not reported.

Abbreviations: RR, response rate; OS, overall survival; 1 Yr, one-year survival; VNR, vinorelbine; CDDP, cisplatin; CBDCA, carboplatin; PAC, paclitaxel; GEM, gemcitabine; CPT-11, irinotecan; DOC, docetaxel; NS, not significant.

For some time, it was felt that a therapeutic plateau had been reached and other treatment strategies were considered. The emergence of third generation chemotherapy agents raised the question as to the necessity of platinum. It was postulated that the combination of two of the newer drugs might be more efficacious and possibly less toxic. Nonplatinum doublets formed the basis of a number of clinical trials (Table 2). Two meta-analyses evaluated treatment outcomes comparing platinum-containing to nonplatinum-containing regimens. Overall both analyses showed increased response rates and one-year survival for the platinum-containing chemotherapy.20,21 However, when platinum-based combinations were compared to combinations that only included third generation drugs, no statistically significant increase in one-year survival was found (36% vs 35%; odd ratio [OR] 1.11; 95% confidence intervals [CI]: 0.96–1.28; P = 0.17).20 Platinum-containing regimens were associated with higher hematologic toxicity, nephrotoxicity, and nausea and vomiting.20,21 Established, efficacious, non-platinum regimens are still considered acceptable forms of treatment if the platinum drugs are contraindicated.

Table 2.

Phase III randomized trials of platin versus nonplatin doublets

| Reference | Patients | Treatment | RR (%) | OS (mo) | 1 Year (%) | P (OS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Georgoulias23 | 406 | DOC/CDDP | 34.6 | 10 | 42 | |

| GEM/DOC | 33.3 | 9.5 | 39 | 0.98 | ||

| Gridelli24 | 501 | GEM/VNR | 25 | 7.4 | 31 | |

| VNR/CDDP or GEM/CDDP | 30 | 8.7 | 37 | 0.08 | ||

| Stathopoulos25 | 360 | CBDCA/PAC | 45.95 | 11 | 42.72 | |

| PAC/VNR | 42.86 | 10 | 37.85 | 0.9545 | ||

| Kosmidis26 | 509 | CBDCA/PAC | 28 | 10.4 | 41.7 | |

| GEM/PAC | 35 | 9.8 | 41.4 | 0.32 | ||

| Pujol27 | 311 | GEM/DOC | 31 | 11.1 | 46 | |

| VNR/CDDP | 35.9 | 9.6 | 42 | 0.47 | ||

| Georgoulias28 | 413 | GEM/DOC | 30 | 9 | 34.3 | |

| VNR/CDDP | 39.2 | 9.7 | 40.8 | 0.965 |

Notes: If more than two regimens were compared in one study, the topmost regimen was the reference regimen and P value is based on comparison to the reference regimen.

Abbreviations: RR, response rate; OS, overall survival; 1 Yr, one-year survival; DOC, docetaxel; CDDP, cisplatin; GEM, gemcitabine; VNR, vinorelbine; CBDCA, carboplatin; PAC, paclitaxel.

Another strategy that has been employed is the use of triplet therapy (Table 3). In a Phase III trial, patients were randomly assigned to receive paclitaxel/carboplatin ± gemcitabine.22 There was a significant improvement in RR (20.2% vs 46%; P < 0.0001), MS (8.3 vs 10.8 months; P = 0.032), and one-year survival (34% vs 45%; P = 0.032) for the triplet therapy group at the expense of more hematologic toxicity, resulting in more transfusions and the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factors. A meta-analysis comparing doublet to triplet chemotherapy found an increase in RR for triplet therapy without a significant survival benefit.14 The current consensus regarding triplet therapy is that the marginal benefit observed on some of the trials is not worth the additional toxicity.

Table 3.

Phase III randomized trials of doublet versus triplet chemotherapy

| Reference | Patients | Treatment | RR (%) | OS (mo) | 1 year (%) | P (OS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laack29 | 287 | GEM/VNR | 13a | 8.3 | 33.6 | |

| GEM/VNR/CDDP | 28.3 | 7.5 | 27.5 | 0.73 | ||

| Paccagnella22 | 324 | CBDCA/PAC | 20b | 8.3 | 34 | |

| CBDCA/PAC/GEM | 43.6 | 10.8 | 45 | 0.032 | ||

| Comella30 | 433 | GEM/VNR | 31 | 8.8 | N/A | N/A |

| GEM/VNR/CDDP | 46 | 10.2 | N/A | N/A | ||

| GEM/PAC | 38 | 11.1 | N/A | N/A | ||

| GEM/PAC/CDDP | 50 | 11.2 | N/A | N/A | ||

| Both Doublets | 35 | 10.5 | 40 | |||

| BothTriplets | 48a | 10.7 | 44 | 0.379 |

Notes: If more than two regimens were compared in one study, the topmost regimen was the reference regimen and P value is based on comparison to the reference regimen.

P = 0.004;

P < 0.0001.

Abbreviations: RR, response rate; OS, overall survival; 1Yr, one year survival; GEM, gemcitabine; VNR, vinorelbine; CDDP, cisplatin; CBDCA, carboplatin; PAC, paclitaxel; N/A, not available.

There has been an ongoing controversy regarding the choice of platinum used in chemotherapy. Cisplatinum is perceived as possibly more efficacious than carboplatin, albeit potentially more toxic. A randomized trial evaluating pacliltaxel and cisplatin or carboplatin had a significantly better MS (8.2 vs 9.8 months; P = 0.019) for the cisplatin combination.17 Toxicities were as expected with more hematolgic toxicity for carboplatin and more nausea/vomiting and nephrotoxicity for cisplatin. A meta-analysis of trials comparing cisplatin and carboplatin-based regimens showed an improved RR (24% vs 30%; OR 1.37; 95% CI: 1.16–1.61; P < 0.001), but OS was not significantly different (hazard ratio [HR] 1.07; 95% CI: 0.99–1.15; P = 0.100).31 In subgroup analyses, cisplatin was associated with a statistically significant improvement in OS in patients with non-squamous histology (HR 1.12; 95% CI: 1.01–1.23) and those who received third generation chemotherapy (HR 1.11; 95% CI: 1.01–1.21). Choice of platinum should be based on the treatment goal. For example, when the disease is potentially curable as in the adjuvant setting, cisplatin may be the platinum of choice. In the metastatic situation where the goal of treatment is palliation of symptoms, patient convenience and potential toxicities should be considered when choosing a chemotherapy regimen.

Pemetrexed is a multitargeted antifolate that is a relative new comer in the treatment of NSCLC. Initially it was found to have efficacy in second-line treatment.32 An intriguing retrospective analysis of outcome by histology suggested that pemetrexed may be more beneficial for patients with nonsquamous histology.33 A large Phase III trial in chemonaïve patients comparing cisplatin/gemcitabine (CG) with cisplatin/pemetrexed (CP) showed similar efficacy with a median OS of 10.3 months for both regimens (HR 0.94; 95% CI 0.84–1.05).6 In a preplanned subgroup analysis patients with non-squamous histology had significantly improved OS with CP compared to CG (11.8 vs 10.4 months; HR 0.81; 95% CI 0.70–0.94; P = 0.005). Patients with squamous histology benefited more from CG than CP (median OS 9.4 vs 10.8 months; HR 1.23; 95% CI 1.00–1.51; P = 0.05). This was the first large Phase III study to show a survival benefit in certain histologic subgroups by specific chemotherapy. Histologic determination may also be important with regard to toxicity considerations. A randomized Phase II trial employed bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody to VEGF (see following section on molecularly targeted agents) in combination with carboplatin/paclitaxel for patients with advanced NSCLC.34 Six patients had life-threatening pulmonary hemorrhage on the trial. The incidence was 31% in squamous cell carcinoma patients versus only 4% in adenocarcinoma. Therefore, it appears that specific histologic diagnosis may determine treatment selection for safety, as well as efficacy.

Targeted agents in combination with chemotherapy

In the past decade a number of new agents have been developed against novel targets in the cancer cell. EGFR is expressed in 40%–80% of lung cancers and its aberrant activation is important in the malignant process.35 Gefitinib and erlotinib are the first drugs developed to inhibit the tyrosine kinase (TK) activity of EGFR. Both had promising activity as single agents with an acceptable toxicity profile consisting primarily of an acneiform rash and diarrhea. A more concerning side effect was the development of interstitial pneumonitis in about 1% of the patients. The second-line use of these agents will be discussed later in this review. Excitement over the novel EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) resulted in their expeditious combination with chemotherapy. There were four large Phase III randomized placebo-controlled trials (INTACT 1 and 2, TRIBUTE, and TALENT) comparing chemotherapy (either cisplatin/gemcitabine or carboplatin/paclitaxel) with or without gefitinib or erlotinib in chemotherapy-naïve patients with NSCLC.36–39 The regimens were well tolerated, but there was no improvement in OS, time to progression (TTP), or RR by combining chemotherapy with an EGFR-TKI. A large proportion of the study population was Caucasian and/or male, which could potentially explain the negative results. Only TRIBUTE collected extensive smoking history and it demonstrated a substantially improved 22.5 month OS in never-smokers who received carboplatin/paclitaxel and erlotinib compared to 10.1 months for the chemotherapy + placebo study arm (HR 0.49; 95% CI: 0.28–0.85).38 Currently, the EGFR-TKIs should not be used in combination with chemotherapy outside a clinical trial.

Bevacizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody to VEGF. The expression of VEGF on tumor cells or in serum may be associated with a worse prognosis.40,41 Bevacizumab has negligible activity against NSCLC as a single agent but was studied in combination with chemotherapy in a randomized Phase II trial.34 Patients received carboplatin/paclitaxel alone or with either 7.5 or 15 mg/kg of bevacizumab. Survival data looked most promising for the higher dose of bevacizumab so this dose was chosen for further study. This trial also established certain patient eligibility criteria (ie, non-squamous histology, no history of hemoptysis, no brain metastases, no full dose anticoagulation, etc) for the Phase III study because of an increased incidence of pulmonary hemorrhage in patients with squamous histology and the concern for potential hemorrhage at other sites.

ECOG 4599 is a Phase III trial that randomized 878 patients to receive carboplatin/paclitaxel ± bevacizumab in advanced non-squamous NSCLC.42 The bevacizumab group received maintenance bevacizumab after 6 cycles of treatment if the disease did not progress. The addition of bevacizumab improved median PFS from 4.5 months to 6.2 months (HR 0.66; 95% CI: 0.57–0.77; P < 0.001) and median OS from 10.3 months to 12.3 months (HR 0.79; 95% CI: 0.67–0.92; P = 0.003). There were more adverse events (ie, grade 4 neutropenia 16.8% vs 25.5%) and treatment-related deaths, (2 patients vs 15 patients) in the bevacizumab group. Febrile neutropenia and pulmonary hemorrhage each resulted in 5 deaths on the bevacizumab study arm. Despite the increase in toxicity, treatment with bevacizumab and chemotherapy resulted in a milestone one-year survival of greater than 50%.

Another international Phase III study (AVAiL, n = 1043) compared cisplatin/gemcitabine with either placebo or high dose (15 mg/kg) or low dose (7.5 mg/kg) bevacizumab in non-squamous NSCLC.43 Addition of bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg increased median PFS from 6.1 months to 6.7 months (HR 0.75; 95% CI: 0.62–0.91; P = 0.003) and to 6.5 months with the 15 mg/kg dose (HR 0.82; 95% CI: 0.68–0.98; P = 0.03). Overall survival was not significantly improved for the bevacizumab-treated patients. There is no specific explanation for this disparity of results with regard to overall survival between these Phase III trials. It should be noted that the incidence of fatal pulmonary hemorrhage was only 1% for the bevacizumab-treated group on AVAiL despite inclusion of patients on anticoagulation. To date there are no specific molecular tissue or serum markers that identify a patient population more likely to benefit from bevacizumab.

Cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody against EGFR, has an established role in the treatment of colon and head and neck cancer. In BMS 099, unselected patients with advanced NSCLC were randomized to receive carboplatin/taxane ± cetuximab.44,45 There was no apparent survival benefit for the patients treated with chemotherapy and cetuximab. The median PFS was 4.4 months in the cetuximab group vs 4.24 months in the control group (HR 0.902; 95% CI: 0.761–1.069; P = 0.2358) and median OS was 9.53 months vs 8.38 months (HR 0.931; 99.99% CI: 0.638–1.359; P = 0.4639).

The FLEX trial randomized patients with advanced NSCLC that expressed EGFR by immunohistochemistry (IHC) on at least 1% of tumor cells to receive cisplatin/vinorelbine ± cetuximab.46 Median OS was significantly increased from 10.1 to 11.3 months (HR 0.871; 95% CI: 0.762–0.996; P = 0.044) with the addition of cetuximab to the chemotherapy. Any grade 4 adverse event was increased by 10% with the triplet therapy. Efficacy was seen regardless of histology and molecular correlative analyses in FLEX and BMS 099 suggesting that neither KRAS mutational status nor EGFR gene copy number by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was predictive of response or survival benefit from cetuximab.47,48 Interestingly, skin rash of any grade in the first cycle of cetuximab treatment was predictive for improved overall survival (8.8 vs 15.0 months) on the FLEX trial.47 It is very important to discover both clinical and molecular determinants of outcome considering the modest survival benefit afforded by treatment with cetuximab. Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) 0819 is an ongoing trial that randomizes patients to receive carboplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab ± cetuximab. There is a co-primary analysis requiring over 600 patients to evaluate survival in those participants with EGFR FISH positive tumors (NCT00596830, www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Maintenance chemotherapy

Optimal duration of chemotherapy is unclear.49–53 A Phase III study evaluating continuation of the initial chemotherapy until disease progression did not show improved survival compared to delivery of a fixed number of 4 cycles.50 Another Phase III trial compared maintenance gemcitabine to best supportive care after achievement of disease control (response and/or stable disease) with 4 cycles of gemcitabine/cisplatin.54 Maintenance gemcitabine increased time to progression (TTP) by 3.6 months compared to 2.0 months for best supportve care (HR 0.7; 95% CI: 0.5–0.9; P < 0.001), but OS, although better, was not significantly improved (13.0 vs 11.0 months; P = 0.195). Another trial used docetaxel either immediately after completion of 4 cycles of gemcitabine/carboplatin (immediate treatment group) or only upon progression (delayed group).55 The immediate treatment group had a longer median PFS of 5.7 months compared to 2.7 months for the delayed treatment group (P < 0.001). There was a trend for a better OS (12.3 vs 9.7 months; P = 0.0853) for the patients receiving immediate docetaxel. However, only 63% of the delayed group actually received docetaxel upon disease progression compared to 95% in the immediate treatment group. Delayed group patients who did receive docetaxel had a similar OS (12.5 months). Adverse events and QOL scores were not different between the groups.

In a large Phase III trial, patients treated with 4 cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy who did not have progressive disease were randomized to receive pemetrexed or placebo.56 The initial chemotherapy did not contain pemetrexed. Maintenance pemetrexed improved PFS (4.4 vs 1.8 months; HR 0.47; 95% CI: 0.37–0.6; P < 0.00001) and OS (15.5 vs 10.3 months; HR 0.70; 95% CI: 0.56–0.88; P = 0.002) only in patients with non-squamous histology. Many feel that the appropriate terminology in this instance is not maintenance therapy, but rather early second-line treatment. Only 19% of the placebo group received pemetrexed upon disease progression. It is unknown whether the delivery of pemetrexed on disease progression in the placebo group would have resulted in a similar outcome.

The SATURN study had a similar design to the pemetrexed trial, but used erlotinib as maintenance.57 The patients who received erlotinib had a modest but statistically significant improved median PFS (12.3 vs 11.1 weeks; HR 0.71; 95% CI: 0.62–0.82; P < 0.0001) and median OS (11 vs 12 months; HR 0.81; 95% CI: 0.70–0.95; P = 0.0088).58 All clinical subgroups benefited. Molecular correlate analyses indicated that patients with EGFR gene mutations had a significantly better PFS (HR 0.10; 95% CI: 0.04–0.25; P < 0.0001). Even patients who had wild type EGFR or squamous cell histology had an improved PFS with erlotinib although the magnitude of benefit was much smaller than in EGFR-mutated or adenocarcinoma patients. The clinical significance of this modest benefit is debatable. Again only 21% of the placebo group received erlotinib upon disease progression. The ATLAS study compared maintenance bevacizumab plus erlotinib to bevacizumab plus placebo after 4 cycles of a platinum containing doublet with bevacizumab.59 The combination of bevacizumab plus erlotinib had better PFS compared to bevacizumab plus placebo (4.76 vs 3.75 months; HR 0.722; 95% CI: 0.592–0.881; P = 0.0012). Overall survival and the results of the molecular correlative studies have not been reported.

It is not clear how pemetrexed maintenance will fit into current practice especially with its use as part of first-line therapy. Maintenance therapy is not without its side effects and will have to be considered on an individual patient basis. Based on the Fidias trial there is concern that if additional therapy is delayed until disease progression some patients may not get the benefit of second-line treatment.55 Patients not continuing treatment in a maintenance fashion would have to be carefully monitored for disease progression so that additional therapy can be started at the first indication of progression.

Second-line chemotherapy

The role of second-line chemotherapy for NSCLC was established a decade ago.60,61 The initial Phase III study randomly assigned 204 previously treated, taxane naïve NSCLC patients to either receive docetaxel or best supportive care alone.60 Response rate was only 7% for docetaxel, but median OS (7.0 vs 4.6 months; P = 0.047) and QOL were improved. TAX 320 compared docetaxel at two doses (75 or 100 mg/m2) to either vinorelbine or ifosfamide as second-line treatment.61 One third of the participants were pretreated with paclitaxel. Crossover from vinorelbine or ifosfamide to docetaxel upon disease progression was common and MS was similar in all three groups, with docetaxel at 75 mg/m2 resulting in the best one-year survival. Docetaxel had a higher incidence of grade 3/4 hematologic toxicities. Previous treatment with paclitaxel did not influence patient outcome. These trials established docetaxel as the reference chemotherapy for second-line treatment. There has been interest in the weekly administration of docetaxel in order to reduce adverse events while retaining efficacy. Three randomized trials did not show any survival difference between the weekly and every 3 week administration schedules and weekly docetaxel was associated with less neutropenia.62–64 There is insufficient data to support the use of doublet chemotherapy as second-line treatment. A meta-analysis evaluating single agent and doublet chemotherapy in the second-line setting showed a higher RR when two drugs were used (15.1 vs 7.3%; P = 0.0004), with no difference in OS (37.3 vs 34.7 weeks; HR 0.92; 95% CI: 0.79–1.08; P = 0.32).65 Until further evidence is available, single agent therapy is recommended for second-line treatment.

Pemetrexed first established its role in the treatment of NSCLC in the second-line setting. In a large Phase III trial pemetrexed was compared to docetaxel.32 Treatment with pemetrexed had a comparable RR of 9.1% compared to 8.6% for docetaxel (P = 0.105) and an equivalent median OS (8.3 vs 7.9 months respectively; HR 0.99; 95% CI: 0.82–1.2; P = 0.226). QOL was similar between treatment groups, however pemetrexed had fewer hematologic toxicities and hospitalizations. A retrospective subset analysis suggested that pemetrexed was more effective for patients with nonsquamous histology.33

Gefitinib and erlotinib are EGFR-TKIs that have been tested in the second-line setting in multiple trials.66–71 Gefitinib was evaluated in the Phase II Iressa Dose Evaluation in Advanced Lung (IDEAL) trials.66,67 The drug was approved based on these studies because of its ability to provide meaningful benefit as second-line treatment for patients with NSCLC. In the Phase III ISEL trial, 1692 previously treated patients were randomized to receive gefitinib 250 mg or placebo.70 Unfortunately, there was not a significant survival advantage for the gefitinib-treated patients compared to placebo (OS 5.6 vs 5.1 months for placebo; HR 0.89; 95% CI: 0.77–1.02; P = 0.087). A post-hoc analysis showed improved survival in never-smokers and Asian patients. Gefitinib was withdrawn from the US market after the negative result of the ISEL trial. The BR.21 study (n = 731) compared erlotinib to placebo in previously treated patients.71 Daily erlotinib was associated with an improved response (8.9% vs <1%; P <0.001) and prolonged survival (OS 6.7 vs 4.7 months; HR 0.70; 95% CI: 0.58–0.85; P < 0.001). A survival benefit was observed across all treatment groups including the elderly, non-Asians, and patients with squamous cell histology and poor PS.

The INTEREST trial (n = 1466) compared gefitinib with docetaxel in the second-line setting.69 Efficacy was equivalent with a median OS of 7.6 months for gefitinib and 8.0 months for docetaxel (HR 1.020; 96% CI: 0.905–1.150). There was significant crossover treatment at the time of disease progression. Gefitinib treated patients generally had less toxicity and a better QOL. On the BETA trial bevacizumab was combined with erlotinib and compared to erlotinib alone.72 Addition of bevacizumab doubled RR (6.2% vs 12.6%; P = 0.006) and increased PFS (1.7 vs 3.4 months; HR 0.62; 95% CI: 0.52–0.75; P < 0.0001), but did not improve OS (9.2 vs 9.3 months; HR 0.97; 95% CI: 0.80–1.18; P = 0.7583). Many new drugs continue to be evaluated in the second-line setting either alone or in combination with established second-line agents.

Recent trials

There are many trials that are being conducted in the treatment of advanced NSCLC. It is beyond the scope of this review to discuss all of these studies. Some of the trials are attempting to answer questions regarding the use of currently approved agents for NSCLC treatment. For example, ECOG will shortly activate a Phase III trial that will attempt to refine the use of maintenance therapy. Patients who have advanced nonsquamous NSCLC will be treated with carboplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab followed by randomization to maintenance therapy with bevacizumab, pemetrexed, or pemetrexed/bevacizumab. As previously mentioned, SWOG 0819 is a Phase III trial that will evaluate the addition of cetuximab to chemotherapy ± bevacizumab. In a separate prospective analysis the value of EGFR by FISH as a predictive molecular marker for cetuximab activity will also be assessed.

Most of the newer trials involve a plethora of promising novel agents that are being investigated in lung cancer in the first or second-line setting as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy.

Vandetanib, a multitargeted inhibitor of EGFR, VEGFR, and RET is far along in development and has been evaluated in four large Phase III clinical trials as a single agent or in combination with chemotherapy in relapsed NSCLC.73–75 The ZODIAC trial employed docetaxel ± vandetanib while ZEAL utilized pemetrexed ± vandetanib. The combination of docetaxel and vandetinilb had a significant improvement in PFS when compared to docetaxel alone (4.0 vs 3.2 months; HR 0.79; 97.58% CI: 0.70–0.90; P < 0.001), but there was no difference in OS.74 In the ZEAL trial there was no statistically significant survival benefit for the addition of vandetanib to pemetrexed, however it is possible that a smaller patient sample size may have contributed to this outcome.75 The ZEST trial compared vandetanib with erlotinib and the drugs had a similar efficacy.73 Results are awaited from the ZEPHYR trial which compares vandetanib to placebo after EGFR-TKI treatment (NCT00404924 www.clinicaltrials.gov). On the ZODIAC study, multiple biologic markers including EGFR by IHC and FISH, EGFR and KRAS gene mutations, and VEGF/VEGF-2 levels were evaluated, but the number of tumor samples was small and there were no obvious predictive markers. This is unfortunate considering the benefit from vandetanib is very modest and it would be important to discover markers predictive for clinical gain from this drug.

Sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor that targets Raf, VEGF and PDGF receptors, has United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for clear cell carcinoma of the kidney and hepatocellular carcinoma. It has activity against NSCLC and has been tested in a large Phase III study.76 The ESCAPE trial evaluated carboplatin/paclitaxel ± sorafenib in first-line chemotherapy for NSCLC.77 Nine fatal pulmonary hemorrhages occurred exclusively in squamous cell cancer patients, the incidence evenly divided between both study arms. Median OS was similar for both treatment groups but a subgroup analysis showed a detrimental effect for sorafenib in squamous cell histology (median OS 8.9 vs 13.6 months; HR 1.81). There is an ongoing Phase III clinical trial comparing sorafenib to placebo for third or fourth-line treatment of patients with nonsquamous histology (NCT00863746, www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Cediranib is an oral tyrosine kinase selective inhibitor of VEGF. The BR.24 trial randomized patients to receive carboplatin/paclitaxel and cediranib (45 mg or 30 mg) or placebo. Despite an improvement in RR and PFS for the cediranib-treated patients, MS was not improved and there was an increase in adverse events.78 A Phase III trial, BR.29, is planned that will randomize patients to receive chemotherapy ± cediranib at the lower dose of 20 mg (NCT00795340, www.clinicaltrials.gov).

Insulin-like growth factor receptor-1 (IGFR-1) is a transmembrane heterotetrameric protein, encoded by the IGFR-1 gene located on chromosome 15q25–q26, promoting oncogenic transformation, growth, and survival of cancer cells.79 In a randomized Phase II trial, the IGFR-1 antibody, figitumumab (CP-751,871), was combined with carboplatin/paclitaxel and demonstrated a RR of 54% compared to 42% for chemotherapy alone.80 The RR of 78% for patients with squamous histology was particularly impressive and may be related to a higher expression of IGF-1R on the tumor cells. This agent was being evaluated in a Phase III study (NCT00596830, www.clinicaltrials.gov). The trial was terminated early and results are awaited. This represents just a few of the agents that are further along in their development and are being evaluated in Phase III trials.

Future directions

Molecular markers in nonsmall cell lung cancer

The use of various molecular markers to determine treatment is a current trend for research in the treatment of NSCLC. EGF is important in the malignant process and appears to mediate cancer cell growth, proliferation, and metastasis. EGFR is over-expressed in 43%–89% of NSCLC patients, and seemingly, should be an excellent target for cancer treatment.35 However, EGFR expression/over-expression on tumor cells detected by IHC or FISH has had variable correlation with response to EGFR-TKIs.81,82 A deletion mutation in exon 19 and a missense mutation in exon 21 (L858R) have been associated with an increased sensitivity to the EGF-TKIs.83 Exon 19 deletion patients have a longer PFS with erlotinib compared to exon 21 mutation carriers.84 Asian ethnicity, adenocarcinoma histology, never-smoking status, and female sex are clinical characteristics that correlate with a higher incidence of EGFR mutations.85,86

The IPASS study enrolled a clinically-enriched population of NSCLC patients who were more likely to carry the EGFR gene mutation (ie, never/former light smokers, predominantly Asian patients) and randomized them to gefitinib or carboplatin/paclitaxel as initial treatment.87 The incidence of EGFR mutations in the study was 60%. The patients with EGFR mutations had better PFS with gefitinib than carboplatin/paclitaxel (HR 0.48; 95% CI: 0.36–0.64; P < 0.001). The patients who did not have an EGFR gene mutation did significantly worse with gefitinib compared to chemotherapy (HR 2.85; 95% CI: 2.05–3.98; P < 0.001). For the EGFR wild type patients, the response rate in the gefitinib group was only 1% compared to 70% for those who were mutation positive. It is clear that clinical demographics alone should not be used to determine the use of EGFR-TKIs for the treatment of advanced NSCLC in the first-line setting. The tumor should be evaluated for EGFR mutations and if the specimen is not sufficient for analysis or the patient has EGFR wild type then traditional doublet chemotherapy should be utilized.

A large prospective observational study showed feasibility of EGFR mutation analysis in real practice in Spain.84 EGFR mutations were found in 16.6% and RR, median PFS, and OS of the patients with EGFR gene mutations who were treated with erlotinib was 70.6%, 14, and 27 months, respectively, which was comparable to the benefit observed in Asian patients treated with gefitinib. Of note, the PFS and OS of patients who received erlotinib as second or third-line treatment was equivalent to those who received erlotinib first-line. A question arises as to whom should be tested for the EGFR gene mutation. EGFR mutations are uncommon in squamous cell cancer even in the Asian population.85,88 EGFR mutations in current smokers are seen in 5% or less, but were found in approximately 10% of ex-heavy smokers (>50–60 pack-year history of smoking).84,89,90 In addition to patients with more typical demographics associated with EGFR mutations, testing should also be considered in former smokers with adenocarcinoma if an EGFR-TKI is being considered for first-line treatment.

The utility of EGFR analysis prior to treatment in the second-line setting is debatable. On the BR.21 trial, all subgroups benefited from erlotinb, even those who were less likely to carry a mutation (ie, male, squamous cell carcinoma, smoker, non-Asian).71 Subgroup analyses of BR.21 showed that EGFR mutations and high EGFR copy number by FISH predicted a better response rate (27% EGFR mutation positive vs 7% EGFR wild type; P = 0.035, and 5% for EGFR FISH-negative vs 21% for FISH-positive; P = 0.02).91 EGFR copy number was the strongest prognostic marker and a significant predictive indication of survival benefit from erlotinb. On the INTEREST trial that randomized patients being treated second-line to gefitinib or docetaxel, molecular correlative studies were also done.69 There was no demonstrable association between EGFR mutational status and EGFR by IHC and/or FISH and benefit from erlotinib. The results from these correlative studies are often hampered by few and/or inadequate tumor samples. Survival results are further contaminated by crossover treatment after disease progression.

K-RAS gene encodes the intracellular pathway protein of the EGFR signaling cascade and is mutated in 7.9%–28.8% of NSCLC patients.85,92 It has been suggested that K-RAS mutations may be a predictive marker for resistance to erlotinib or gefitinib in NSCLC.93–95 Larger studies are necessary to confirm the predictive value of the mutations, but KRAS gene analysis may be a promising tool in identifying populations who do not respond to EGFR-TKIs. Interestingly, based on the evaluation of tumor samples from the BMS 099 and FLEX trials, KRAS mutations do not appear to predict for disease response from cetuximab treatment as is seen in colon cancer.47,48 EGFR mutations and EGFR analysis by IHC and FISH were also not helpful in determining benefit from cetuximab.

Another area of research involves investigations into the mechanisms of resistance to the EGFR-TKIs. Acquired resistance has been associated with secondary EGFR mutations such as T790M and D761Y.96 Gene amplification of MET, the receptor for hepatocyte growth factor, has also been implicated as a mechanism for resistance.97 Knowledge of these resistance patterns has resulted in the development of a number of new agents that are currently in early clinical development.

Excision repair cross-complementing 1 (ERCC1) plays a key role in DNA excision repair and increased tumor expression has been associated with platinum resistance in vitro and in vivo.98–101 A large Phase III study randomly assigned NSCLC patients to a control or genotypic group.102 The control group received treatment with docetaxel/cisplatin. The genotypic group patients had ERCC1 mRNA analysis on tumor and received docetaxel/cisplatin if ERCC1 expression was low and docetaxel/gemcitabine if ERCC1 expression was high. This prospective customized approach was feasible. The genotypic group had a higher response rate compared to the control group (51.2% vs 39.3%; P = 0.02) with similar survival outcomes for both study arms.

Ribonucleotide reductase subunit 1 (RRM1) gene encodes a subunit of ribonucleotide reductase and its high expression has been associated with resistance to gemcitabine.103 The MADeIT study was a prospective Phase II trial in which advanced NSCLC patients were required to have a tumor biopsy for determination of ERCC1 and RRM1 for subsequent selection of first-line treatment.104 Patients treated by this selection process had a promising response rate of 44% and a one-year survival of 59%. A Phase III trial (NCT00499109, www.clinicaltrials.gov) is currently underway that is using ERCC1 and RRM1 to customize treatment.

Thymidylate synthase (TS), an enzyme that plays an important role in DNA biosynthesis, is a main target of pemetrexed.105 High TS expression in squamous cell carcinoma may account for the inactivity of the drug in this disease.106 TS levels are being prospectively incorporated into clinical trials to assess their predictive potential for pemetrexed activity. It is hoped that all of these molecular markers may aid in therapeutic decision making and eventually improve patient outcome.

A novel fusion of echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 4 (EML4) gene with the intracellular signaling portion of the receptor tyrosine kinase encoded by the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) gene was identified in NSCLC.107 In a Phase I trial, PF-02341066, an oral ALK/MET inhibitor, had a RR of 59% in patients with the EML4-ALK gene fusion.108 The EML4-ALK gene fusion is found in only 3%–4% of lung adenocarcinomas and these patients share some similar clinical characteristics with those who harbor the EGFR gene mutations (ie, never/light – smokers, adenocarcinoma).109–112 There has been a great deal of excitement over this agent despite the fact that only a small number of patients may potentially benefit from it. This illustrates the fact that lung cancer is very heterogenous and an understanding of the biology of individual tumors is of paramount importance.

It is likely that, in the future, treatment will vary widely from patient to patient and that personalized medicine will be the key component in the management of NSCLC. This will happen via scientific correlative studies associated with innovative clinical trial design. The BATTLE study is currently underway at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, Texas, USA, in which 11 biomarkers including EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, Cyclin D1, VEGF, VEGFR-2, and RXR are tested in patients after they have failed first-line chemotherapy.113 Patients are randomized to treatment based on their molecular profiles. A preliminary report indicates the feasibility of this approach and it is hoped this tailor-made therapy can be applied more widely to improve survival for lung cancer patients.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Dr Wozniak received research funding from Lilly and is on their Speaker’s Bureau. Dr. Wozniak is on the Advisory Boards for Lilly, Genentech, OSI, Astrazeneca, and Bristol Myers squibb. Dr Ogita has no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wozniak AJ, Crowley JJ, Balcerzak SP, et al. Randomized trial comparing cisplatin with cisplatin plus vinorelbine in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(7):2459–2465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonomi P, Kim K, Fairclough D, et al. Comparison of survival and quality of life in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with two dose levels of paclitaxel combined with cisplatin versus etoposide with cisplatin: results of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(3):623–631. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fossella F, Pereira JR, von Pawel J, et al. Randomized, multinational, phase III study of docetaxel plus platinum combinations versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the TAX 326 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3016–3024. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandler AB, Nemunaitis J, Denham C, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(1):122–130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3543–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spiro SG, Rudd RM, Souhami RL, et al. Chemotherapy versus supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: improved survival without detriment to quality of life. Thorax. 2004;59(10):828–836. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.020164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ. 1995 Oct 7;311(7010):899–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones AM, Hanson IM, Armstrong GR, O’Driscoll BR. Value and accuracy of cytology in addition to histology in the diagnosis of lung cancer at flexible bronchoscopy. Respir Med. 2001;95(5):374–378. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2001.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards SL, Roberts C, McKean ME, Cockburn JS, Jeffrey RR, Kerr KM. Preoperative histological classification of primary lung cancer: accuracy of diagnosis and use of the non-small cell category. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53(7):537–540. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.7.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khayyata S, Yun S, Pasha T, et al. Value of P63 and CK5/6 in distinguishing squamous cell carcinoma from adenocarcinoma in lung fine-needle aspiration specimens. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37(3):178–183. doi: 10.1002/dc.20975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas JS, Lamb D, Ashcroft T, et al. How reliable is the diagnosis of lung cancer using small biopsy specimens? Report of a UKCCCR Lung Cancer Working Party. Thorax. 1993;48(11):1135–1139. doi: 10.1136/thx.48.11.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grilley-Olson JE, Hayes DN, Qaqish BF, et al. Diagnostic reproducibility of squamous cell carcinoma (SC) in the era of histology-directed non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) chemotherapy: A large prospective study [abstract] J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:8008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delbaldo C, Michiels S, Syz N, Soria JC, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP. Benefits of adding a drug to a single-agent or a 2-agent chemotherapy regimen in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292(4):470–484. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin in the treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(13):3210–3218. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.13.3210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosell R, Gatzemeier U, Betticher DC, et al. Phase III randomised trial comparing paclitaxel/carboplatin with paclitaxel/cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a cooperative multinational trial. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(10):1539–1549. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdf332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scagliotti GV, De Marinis F, Rinaldi M, et al. Phase III randomized trial comparing three platinum-based doublets in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(21):4285–4291. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohe Y, Ohashi Y, Kubota K, et al. Randomized phase III study of cisplatin plus irinotecan versus carboplatin plus paclitaxel, cisplatin plus gemcitabine, and cisplatin plus vinorelbine for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Four-Arm Cooperative Study in Japan. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(2):317–323. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Addario G, Pintilie M, Leighl NB, Feld R, Cerny T, Shepherd FA. Platinum-based versus non-platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of the published literature. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):2926–2936. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajeswaran A, Trojan A, Burnand B, Giannelli M. Efficacy and side effects of cisplatin- and carboplatin-based doublet chemotherapeutic regimens versus non-platinum-based doublet chemotherapeutic regimens as first line treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung carcinoma: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Lung Cancer. 2008;59(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paccagnella A, Oniga F, Bearz A, et al. Adding gemcitabine to paclitaxel/carboplatin combination increases survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a phase II–III study. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(4):681–687. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Georgoulias V, Papadakis E, Alexopoulos A, et al. Platinum-based and non-platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised multicentre trial. Lancet. 2001;357(9267):1478–1484. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04644-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gridelli C, Gallo C, Shepherd FA, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine compared with cisplatin plus vinorelbine or cisplatin plus gemcitabine for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the Italian GEMVIN Investigators and the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(16):3025–3034. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stathopoulos GP, Veslemes M, Georgatou N, et al. Front-line paclitaxel-vinorelbine versus paclitaxel-carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2004;15(7):1048–1055. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kosmidis P, Mylonakis N, Nicolaides C, et al. Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus gemcitabine plus paclitaxel in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(17):3578–3585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pujol JL, Breton JL, Gervais R, et al. Gemcitabine-docetaxel versus cisplatin-vinorelbine in advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III study addressing the case for cisplatin. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(4):602–610. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Georgoulias V, Ardavanis A, Tsiafaki X, et al. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus docetaxel plus gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(13):2937–2945. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laack E, Dickgreber N, Müller T, et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine and vinorelbine versus gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and cisplatin in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: from the German and Swiss Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(12):2348–2356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Comella P, Filippelli G, De Cataldis G, et al. Efficacy of the combination of cisplatin with either gemcitabine and vinorelbine or gemcitabine and paclitaxel in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomised trial of the Southern Italy Cooperative Oncology Group (SICOG 0101) Ann Oncol. 2007;18(2):324–330. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ardizzoni A, Boni L, Tiseo M, et al. Cisplatin-versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(11):847–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(9):1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scagliotti G, Hanna N, Fossella F, et al. The differential efficacy of pemetrexed according to NSCLC histology: a review of two Phase III studies. Oncologist. 2009;14(3):253–263. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson DH, Fehrenbacher L, Novotny WF, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing bevacizumab plus carboplatin and paclitaxel with carboplatin and paclitaxel alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2184–2191. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirsch FR, Scagliotti GV, Langer CJ, Varella-Garcia M, Franklin WA. Epidermal growth factor family of receptors in preneoplasia and lung cancer: perspectives for targeted therapies. Lung Cancer. 2003;41(Suppl 1):S29–S42. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial-INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):777–784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herbst RS, Giaccone G, Schiller JH, et al. Gefitinib in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial-INTACT 2. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(5):785–794. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herbst RS, Prager D, Hermann R, et al. TRIBUTE: a phase III trial of erlotinib hydrochloride (OSI-774) combined with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):5892–5899. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gatzemeier U, Pluzanska A, Szczesna A, et al. Phase III study of erlotinib in combination with cisplatin and gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: the Tarceva Lung Cancer Investigation Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1545–1552. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han H, Silverman JF, Santucci TS, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in stage I non-small cell lung cancer correlates with neo-angiogenesis and a poor prognosis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8(1):72–79. doi: 10.1007/s10434-001-0072-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaya A, Ciledag A, Gulbay BE, et al. The prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor levels in sera of non-small cell lung cancer patients. Respir Med. 2004;98(7):632–636. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(24):2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, et al. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAiL. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lynch TJ, Patel T, Dreisbach L, et al. A randomized multicenter phase III study of cetuximab in combination with taxane/carboplatin versus taxane/carboplatin alone as first-line treatment for patients with advanced/metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:S340. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lynch TJ, Patel T, Dreisbach L, et al. Overall survival results from the phase III trial BMS 099: cetuximab + taxane/carboplatin as 1st-line treatment for advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;2:S305. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pirker R, Pereira JR, Szczesna A, et al. Cetuximab plus chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (FLEX): an open-label randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1525–1531. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60569-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Byrne KJ, Bondarenko I, Barrios C, et al. Molecular and clinical predictors of outcome for cetuximab in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): Data from the FLEX study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:S15. abstract 8007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khambata-Ford S, Harbison CT, Hart LL, et al. K-RAS mutations (MT) and EGFR-related markers as potential predictors of cetuximab benefit in 1st line advanced NSCLC: Results from the BMS099 Study [abstract] J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:S304–S305. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Von Plessen C, Bergman B, Andresen O, et al. Palliative chemotherapy beyond three courses conveys no survival or consistent quality-of-life benefits in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(8):966–973. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Socinski MA, Schell MJ, Peterman A, et al. Phase III trial comparing a defined duration of therapy versus continuous therapy followed by second-line therapy in advanced-stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(5):1335–1343. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soon YY, Stockler MR, Askie LM, Boyer MJ. Duration of chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(20):3277–3283. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.4522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park JO, Kim SW, Ahn JS, et al. Phase III trial of two versus four additional cycles in patients who are nonprogressive after two cycles of platinum-based chemotherapy in non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5233–5239. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barata FJ, Parente B, Teixeira E, et al. Optimal duration of chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: multicenter, randomized, prospective clinical trial comparing 4 vs 6 cycles of carboplatin and gemcitabine. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:S666. Suppl; abstract P2–P235. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brodowicz T, Krzakowski M, Zwitter M, et al. Cisplatin and gemcitabine first-line chemotherapy followed by maintenance gemcitabine or best supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase III trial. Lung Cancer. 2006;52(2):155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fidias PM, Dakhil SR, Lyss AP, et al. Phase III study of immediate compared with delayed docetaxel after front-line therapy with gemcitabine plus carboplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(4):591–598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Belani CP, Brodowicz T, Ciuleanu T, et al. Maintenance pemetrexed (Pem) plus best supportive care (BSC) versus placebo (Plac) plus BSC: A randomized phase III study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:18s. Suppl; abstract CRA8000. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. SATURN: A double-blind, randomized, phase III study of maintenance erlotinib versus placebo following nonprogression with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. Suppl; abstract 8001. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cappuzzo F, Coudert BP, Wierzbicki R, et al. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib as first-line maintenance in NSCLC following non-progression with chemotherapy: results from the phase III SATURN study. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:S289. Suppl 1; abstract A2.1. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller VA, O’Connor P, Soh C, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIIb trial (ATLAS) comparing bevacizumab (B) therapy with or without erlotinib (E) after completion of chemotherapy with B for first-line treatment of locally advanced, recurrent, or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:18s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.3983. Suppl; abstract LBA8002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(10):2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(12):2354–2362. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schuette W, Nagel S, Blankenburg T, et al. Phase III study of second-line chemotherapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with weekly compared with 3-weekly docetaxel. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(33):8389–8395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Camps C, Massuti B, Jiménez A, et al. Randomized phase III study of 3-weekly versus weekly docetaxel in pretreated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Spanish Lung Cancer Group trial. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(3):467–472. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gridelli C, Gallo C, Di Maio M, et al. A randomised clinical trial of two docetaxel regimens (weekly vs 3 week) in the second-line treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. The DISTAL 01 study. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(12):1996–2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Di Maio M, Chiodini P, Georgoulias V, et al. Meta-analysis of single-agent chemotherapy compared with combination chemotherapy as second-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(11):1836–1843. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (The IDEAL 1 Trial) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(12):2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kris MG, Natale RB, Herbst RS, et al. Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290(16):2149–2158. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.16.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maruyama R, Nishiwaki Y, Tamura T, et al. Phase III study, V-15–32, of gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4244–4252. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9652):1809–1818. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hainsworth J, Herbst RS. A Phase III multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of Bevacizumab in combination with Erlotinib compared with Erlotinib alone for treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer after failure of standard first-line chemotherapy (BETA); Presented at the 2008 Chicago Multidisciplinary Symposium in Thoracic Oncology; Nov, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Natale RB, Thongprasert S, Greco FA, et al. Vandetanib versus erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after failure of at least one prior cytotoxic chemotherapy: A randomized, double-blind phase III trial (ZEST) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. Suppl; abstract 8009. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Herbst RS, Sun Y, Korfee S, et al. Vandetanib plus docetaxel versus docetaxel as second-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A randomized, double-blind phase III trial (ZODIAC) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:18s. Suppl; abstract 8003. [Google Scholar]

- 75.De Boer R, Arrieta Ó, Gottfried M, et al. Vandetanib plus pemetrexed versus pemetrexed as second-line therapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A randomized, double-blind phase III trial (ZEAL) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5717. Suppl; abstract 8010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ng R, Chen EX. Sorafenib (BAY 43-9006): review of clinical development. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2006;1(3):223–228. doi: 10.2174/157488406778249325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Scagliotti G, von Pawel J, Reck M, et al. Phase III trial comparing carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without sorafenib in chemonaive patients with stage IIIB (with effusion) or IV non-small cell lung cancer; Presented at: IASLC-ESMO 1st European Lung Cancer Conference; April 23–26, 2008; Geneva, Switzerland. Late breaking abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goss GD, Arnold A, Shepherd FA, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel with either daily oral cediranib or placebo in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: NCIC clinical trials group BR24 study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):49–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Camidge DR, Dziadziuszko R, Hirsch FR. The rationale and development of therapeutic insulin-like growth factor axis inhibitors for lung and other cancers. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10(4):262–272. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Karp DD, Paz-Ares LG, Novello S, et al. Phase II study of the anti-insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor antibody CP-751,871 in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in previously untreated, locally advanced, or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2516–2522. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsao MS, Sakurada A, Cutz JC, et al. Erlotinib in lung cancer - molecular and clinical predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(2):133–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fukuoka M, Wu Y, Thongprasert S, et al. Biomarker analyses from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib (G) versus carboplatin/paclitaxel (C/P) in clinically selected patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) in Asia (IPASS) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4235. Suppl; abstract 8006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, et al. Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):958–967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marchetti A, Martella C, Felicioni L, et al. EGFR mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer: analysis of a large series of cases and development of a rapid and sensitive method for diagnostic screening with potential implications on pharmacologic treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(4):857–865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bell DW, Lynch TJ, Haserlat SM, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations and gene amplification in non-small-cell lung cancer: molecular analysis of the IDEAL/INTACT gefitinib trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(31):8081–8092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.7078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wiwanitkit V. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung: pattern of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation distribution in different populations: a summary. Lung. 2006;184(5):301–302. doi: 10.1007/s00408-005-2595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pham D, Kris MG, Riely GJ, et al. Use of cigarette-smoking history to estimate the likelihood of mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor gene exons 19 and 21 in lung adenocarcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(11):1700–1704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jida M, Toyooka S, Mitsudomi T, et al. Usefulness of cumulative smoking dose for identifying the EGFR mutation and patients with non-small-cell lung cancer for gefitinib treatment. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(10):1931–1934. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhu CQ, da Cunha Santos G, Ding K, et al. Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(26):4268–4275. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Molecular predictors of outcome with gefitinib in a phase III placebo-controlled study in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(31):5034–5042. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, et al. KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2(1):e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Massarelli E, Varella-Garcia M, Tang X, et al. KRAS mutation is an important predictor of resistance to therapy with epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(10):2890–2896. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.van Zandwijk N, Mathy A, Boerrigter L, et al. EGFR and KRAS mutations as criteria for treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: retro- and prospective observations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(1):99–103. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Balak MN, Gong Y, Riely GJ, et al. Novel D761Y and common secondary T790M mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung adenocarcinomas with acquired resistance to kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6494–6501. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hoeijmakers JH, Bootsma D. DNA repair. Incisions for excision. Nature. 1994;371(6499):654–655. doi: 10.1038/371654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li Q, Yu JJ, Mu C, et al. Association between the level of ERCC-1 expression and the repair of cisplatin-induced DNA damage in human ovarian cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2000;20(2A):645–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Olaussen KA, Dunant A, Fouret P, et al. DNA repair by ERCC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(10):983–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rosell R, Lord RV, Taron M, Reguart N. DNA repair and cisplatin resistance in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;38(3):217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00224-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cobo M, Isla D, Massuti B, et al. Customizing cisplatin based on quantitative excision repair cross-complementing 1 mRNA expression: a phase III trial in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2747–2754. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bepler G, Kusmartseva I, Sharma S, et al. RRM1 modulated in vitro and in vivo efficacy of gemcitabine and platinum in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(29):4731–4737. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Simon G, Sharma A, Li X, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of molecular analysis-directed individualized therapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(19):2741–2746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chattopadhyay S, Moran RG, Goldman ID. Pemetrexed: biochemical and cellular pharmacology, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6(2):404–417. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ceppi P, Volante M, Saviozzi S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung compared with other histotypes shows higher messenger RNA and protein levels for thymidylate synthase. Cancer. 2006;107(7):1589–1596. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small-cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448(7153):561–566. doi: 10.1038/nature05945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shaw AT, Costa DB, Iafrate AJ. Clinical activity of the oral ALK and MET inhibitor PF-02341066 in non-small lung cancer (NSCLC) with EML4-ALK translocations. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:S305. Suppl 1; abstract A6.4. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Inamura K, Takeuchi K, Togashi Y, et al. EML4-ALK fusion is linked to histological characteristics in a subset of lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2008 Jan;3(1):13–17. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31815e8b60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wong DW, Leung EL, So KK, et al. The EML4-ALK fusion gene is involved in various histologic types of lung cancers from nonsmokers with wild-type EGFR and KRAS. Cancer. 2009;115(8):1723–1733. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Perner S, Wagner PL, Demichelis F, et al. EML4-ALK fusion lung cancer: a rare acquired event. Neoplasia. 2008;10(3):298–302. doi: 10.1593/neo.07878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(26):4247–4253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kim ES, Herbst RS, Lee JJ, et al. Phase II randomized study of biomarker-directed treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): The BATTLE (Biomarker-Integrated Approaches of Targeted Therapy for Lung Cancer Elimination) clinical trial program. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. Suppl; abstract 8024. [Google Scholar]