Abstract

Depression and anxiety are common among persons recently diagnosed with HIV infection. We examined whether depression or anxiety was associated with delayed initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) among a prospective cohort of Chinese men who have sex with men (MSM) who were newly diagnosed with HIV. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used for measuring depression and anxiety, with scores of 0–7, 8–10, and 11–21 representing normal, borderline, and likely, respectively. ART initiation information was extracted from the National ART Database. Cox regression was performed to assess associations between HADS scores and the time to ART initiation. Of 364 eligible participants enrolling in the cohort within a median of 11 days after HIV diagnosis, 62% initiated ART during the 12-month follow-up period. The baseline prevalence for likely/borderline depression was 36%, and likely/borderline anxiety was 42%. In adjusted analyses, compared with a depression score of 0, the likelihood of starting ART was 1.82 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.38–2.41], 3.11 (95% CI: 1.82–5.30), and 2.53 (95% CI: 1.48–4.32) times higher for depression scores of 3, 9, and 13, respectively. A similar pattern was observed for the anxiety score. In contrast to our hypothesis, both depression and anxiety were associated with earlier ART initiation among Chinese MSM with newly diagnosed HIV. We speculate that individuals who are more concerned about their new HIV diagnosis may be more likely to seek HIV care and follow a doctor's advice. The effects of depression or anxiety on ART initiation likely differ in varying subgroups and by symptom severity.

Keywords: : depression, anxiety, antiretroviral therapy, men who have sex with men, newly diagnosed HIV infections, China

Introduction

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimated that in 2012, 35 million people were living with HIV/AIDS, and 2.3 million new HIV infections occurred worldwide.1 Men who have sex with men (MSM) have been disproportionately represented among HIV/AIDS cases in several regions, such as North and South America and Asia.1–3 In the United States, 64% of new HIV infections were from MSM in 2012.4 In China, HIV prevalence in MSM has risen from 0.9% in 2003 to 7.7% in 2014; MSM accounted for 25.8% of new HIV cases in 2014.5 Behavioral change and condom promotion have not brought sustained prevention success among MSM.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) can play an important role in preventing HIV transmission through reducing viral load to undetectable levels in blood and other bodily fluids in infected persons. Early and sustained HIV treatment would provide this public health benefit and also reduce opportunistic infections and HIV/AIDS-related death, benefiting ART recipients.6,7 Yet, coverage of ART is still low among people living with HIV (PLWH). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 46% (43–50%) of PLWH were receiving antiretroviral treatment in 2015 worldwide. In China, 59% of PLWH were on ART in 2014.5 Even the Chinese government has revised guidelines encouraging initiation of ART regardless of CD4 count since 2013, a substantial proportion of PLWH do not start ART promptly after HIV diagnosis.

Barriers to ART initiation can emerge from individual, relationship, community, and policy levels.8 Mental health is an important factor at the individual level, and depression and anxiety are common among PLWH. A meta-analysis reported a 39% [95% confidence interval (CI): 33–45%] current prevalence of depression among PLWH.9 Two studies among HIV-infected MSM showed that the current prevalence of depression was 29% in India and 58% in the United States.10,11 For anxiety, a prevalence of 24% in India and 38% in the United States was reported.10,11 HIV-infected MSM may be more prone to depression and/or anxiety due to social isolation and dual stigmatization related to homosexuality and HIV infection.12–15 Treatment of depression and anxiety is cost-effective even in low- and middle-income countries, and could bring benefits in multiple health outcomes.16

Depression has been reported to be associated with delayed initiation of ART among PLWH.17–22 However, there are inconsistent findings.23–25 No study of depression or anxiety and ART initiation in newly diagnosed persons has been published. Anxiety is as common as depression in PLWH, but only one published study has examined its association with ART use.26 In this study, we evaluated the relationship between baseline depression/anxiety and initiation of ART among a prospective cohort of Chinese MSM with newly diagnosed HIV and hypothesized that depression and anxiety would delay ART initiation.

Methods

Study design and population

Our study used the data from the Multi-component HIV Intervention Packages for Chinese MSM project (China MP3). China MP3 had two phases. In the Phase I study, 3588 Chinese MSM with HIV seronegative or unknown status were offered free HIV testing in Beijing. Four hundred fifty-five (12.7%) men were Western blot confirmed as HIV seropositive. These infected participants were then invited to participate in the Phase II—a randomized clinical trial (RCT) aiming to assess the effect of peer counseling on HIV linkage to care among Chinese MSM with newly diagnosed HIV infections in Beijing (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01904877). The RCT was conducted between March 2013 and May 2015. To be eligible, participants in the RCT had no intention of leaving Beijing in the next 12 months and provided informed consent. Enrollment into the RCT occurred a median of 11 days [interquartile range (IQR): 6–22 days] following the HIV diagnosis. We recruited 367 of the 455 (81%) newly diagnosed MSM into the RCT, which served as the population for the current study. This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University and the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention (NCAIDS) of China Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data collection

Sociodemographic characteristics were collected in the Phase I study. Behavioral information was gathered at the baseline survey and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of follow-up surveys in the RCT. We measured drug and alcohol use, and ART adherence in the past 3 months in these surveys. Depression and anxiety,27 quality of life, self-efficacy,28 and stigma related to homosexuality,29 and HIV/AIDS30 were measured at baseline, and at 6 and 12 months of follow-ups only.

Measurement of depression and anxiety

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to screen current depression and anxiety,27 which includes seven items for depression and seven items for anxiety. Each item has four responses (scores from 0 to 3). The total possible scores for depression/anxiety range from 0 to 21 each. HADS scores of 0–7 are considered “normal,” scores of 8–10 are defined as “borderline” depression or anxiety, and scores of 11–21 are defined as “likely” depression or anxiety. Categorization can be clinically meaningful, but it assumes that any effect seen is the same within categories, which might not be true. Hence, we used both the categorical and continuous formats of depression and anxiety scores to model their relationships with ART initiation.

Definition of ART initiation

In our study, we used the date of picking up ART in HIV clinics for the first time to indicate ART initiation. We extracted these dates from the national HIV ART database after the RCT ended. Hence, we could assess all participants' status of ART initiation in the 12 months of follow-up period from the unique identifiers (identity card number of the People's Republic of China) that guaranteed free ART throughout China. For individuals who initiated ART during the 12 months of follow-up, the observational time was the time interval between the date of enrollment and the date of picking up ART medications for the first time. For those who did not initiate ART within 12 months of follow-up, their observational time was the entire follow-up time interval.

Statistical analysis

Of 367 RCT participants, three (<1%) initiated ART before enrollment, leaving a sample size of 364. We conducted bivariate analyses to summarize associations between demographic/behavioral variables and ART initiation, which was treated as a binary outcome (yes or no). In primary analyses, the association [summarized by hazard ratios (HRs)] between depression/anxiety and the time until ART initiation was estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models. A priori substantive knowledge, aided by causal graphs, guided the selection of confounding covariates to be included in the multivariable models.31 These variables included age, study arm (intervention vs. standard of care), study site, quality of life, social support, alcohol use, drug use, residency in Beijing, and HIV-related stigma. Depression/anxiety can lead to substance use (alcohol and drug use) and vice versa.32 Hence, we performed a sensitivity analysis by specifying a second multivariable Cox model that included all variables mentioned above but excluded alcohol use and drug use. HIV-related stigma and clinical trial study arm were tested for potential effect modifications. We also examined the linearity of the log hazards for depression and anxiety scores, age, quality of life, depression/anxiety score, and HIV-related stigma using likelihood ratio tests; when appropriate, restricted cubic splines were used to model nonlinear relationships. CD4 count is an important indicator for ART initiation and it could also be on the causal pathway between depression or anxiety and ART initiation.33 Hence, we additionally adjusted for CD4 count to estimate the direct effect of depression/anxiety (not through CD4 count) on ART initiation. All analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Demographics of study participants

Among 364 participants, the median age was 28 years (IQR: 25–32). Most were of Han ethnicity (93%) and single (84%), had a college education (77%), were employed (83%), and did not have Beijing “Hukou” (or registered household residence; 82%). Over half of participants (55%) had health insurance. Fifty-five percent were alcohol users and 33% reported drug use in the past 3 months. The syphilis coinfection rate was 14% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics Among 364 Chinese Men Who Have Sex with Men with Newly Diagnosed HIV Infections by Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy

| ART initiation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Covariates | No (N = 140, %) | Yes (N = 224, %) |

| Age (median, IQR, years) | 27 (25, 33) | 28 (25, 32) |

| Study arm | ||

| Intervention | 65 (46.4) | 108 (48.2) |

| Control | 75 (53.6) | 116 (51.8) |

| Study site | ||

| Xicheng Clinic | 69 (49.3) | 101 (45.1) |

| Chaoyang Clinic | 71 (50.7) | 123 (54.9) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Han | 129 (92.1) | 210(93.8) |

| Others | 11 (7.9) | 14 (6.2) |

| Married status | ||

| Single | 113 (80.7) | 193 (86.2) |

| Currently married | 21 (15.0) | 22 (9.8) |

| Divorced/separated | 6 (4.3) | 9 (4.0) |

| Education* | ||

| College education or over | 96 (68.6) | 183 (81.7) |

| High school or less educated | 44 (31.4) | 41 (18.3) |

| Employment status* | ||

| Employed | 107 (76.4) | 194 (86.6) |

| Unemployed or other | 33 (23.6) | 30 (13.4) |

| Healthcare | ||

| Yes | 72 (51.4) | 129 (57.6) |

| No | 68 (48.6) | 95 (42.4) |

| Place of birth | ||

| Large cities | 34 (24.3) | 56 (25.0) |

| Medium cities | 31 (22.1) | 57 (25.5) |

| Small cities | 32 (22.9) | 46 (20.5) |

| Township/countryside | 43 (30.7) | 65 (29.0) |

| Resident in Beijing | ||

| Yes | 22 (15.7) | 43 (19.2) |

| No | 118 (84.3) | 181 (80.8) |

| Alcohol use in the past 3 months† | ||

| Never | 65 (46.4) | 99 (44.2) |

| Once or more | 75 (53.6) | 125 (55.8) |

| Drug use in the past 3 months | ||

| Never | 103 (73.6) | 140 (62.5) |

| Once or more | 37 (26.4) | 84 (37.5) |

| Satisfaction with support from friends and/or family members | ||

| Very satisfied | 56 (40.0) | 95 (42.4) |

| Somewhat satisfied | 37 (26.4) | 71 (31.7) |

| Somewhat dissatisfied | 20 (14.3) | 33 (14.7) |

| Very dissatisfied | 27 (19.3) | 25 (11.2) |

| Quality of life (median, IQR) | 80 (60, 80) | 70 (60, 80) |

| Depression Score (median, IQR) | 4 (2, 8) | 7 (4, 10) |

| Depression categories | ||

| Normal (0–7) | 104 (74.3) | 129 (57.6) |

| Borderline depression (8–10) | 14 (10.0) | 44 (19.6) |

| Likely depression (11–21) | 22 (15.7) | 51 (22.8) |

| Anxiety Score (median, IQR) | 4 (2, 9) | 7 (4, 11) |

| Anxiety categories | ||

| Normal (0–7) | 93 (66.4) | 115 (51.3) |

| Borderline anxiety (8–10) | 21 (15.0) | 46 (20.5) |

| Likely anxiety (11–21) | 26 (18.6) | 63 (28.2) |

| Syphilis serostatus | ||

| Negative | 117 (83.6) | 196 (87.5) |

| Positive | 23 (16.4) | 28 (12.5) |

| CD4+ T cell count at baseline (cell/μL, median, IQR) | 469 (375, 597) | 369 (267, 454) |

| Viral load at baseline (IU/mL, median, IQR) | 38,800 (17, 200, 93,500) | 59,900 (26,400, 162,000) |

p < 0.05; †p < 0.1.

ART, antiretroviral therapy; CI, confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range.

At baseline, the median depression score was 6 (IQR: 3, 9), with depression prevalence of 36% (16% borderline and 20% likely depression). The median anxiety score was 7 (IQR: 3, 10), with anxiety prevalence of 42% (18% borderline and 24% likely anxiety). The prevalence of comorbid depression and anxiety was 32% (117/364) at baseline. The proportion of individuals with only depression or anxiety symptoms was 11.3%. Depression and anxiety scores were highly correlated (Spearman's rank correlation [r]: 0.88, p < 0.001).

ART initiation during 12 months of follow-up

During the 12 months of follow-up, 224 of 364 (62%) participants initiated ART, with most (78%) prescribed the combination of efavirenz/lamivudine/tenofovir. Of the 224 ART initiators, 179 (80%) initiated ART before 3 months of follow-up, 15 (7%) between 3 and 6 months, 19 (8%) between 6 and 9 months, and 11 (5%) between 9 and 12 months. MSM who initiated ART were more likely to be single, college educated, employed, well supported by family members and/or friends, and had a lower baseline CD4 count. Contrary to our hypothesis, they were also more likely to be screened as having depression and/or anxiety (Table 1).

Association between continuous depression/anxiety scores and ART initiation

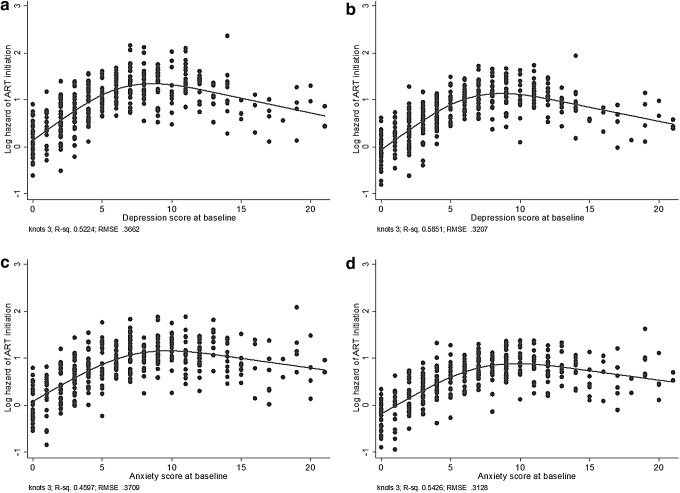

The relationships between the depression or anxiety scores and the log hazard of starting ART were not linear (p < 0.05 for both). Hence, restricted cubic splines were used to model their associations with ART initiation. Neither the intervention arm nor HIV-related stigma was an effect modifier for the effect of depression or anxiety on ART initiation. Figure 1a and b shows that the hazard of starting ART increased with depression score increasing between 0 and 7, followed by a nearly flat slope in the score range of 8–10, and then a slowly descending trend with scores between 11 and 21. Figure 1c and d shows a similar trend between anxiety scores and the hazard of ART initiation. The median scores in those three intervals were used in Table 2 to present HRs between depression/anxiety and ART initiation from the various models, with a score of zero as the reference. For the primary model (Model-1a) and compared with a depression score of 0, the hazard of starting ART was 1.82 (95% CI: 1.38–2.41), 3.11 (95% CI: 1.82–5.30), and 2.53 (95% CI: 1.48–4.32) times higher for depression scores of 3, 9, and 13, respectively. For anxiety, a similar pattern was observed except that the HRs were slightly less than those for depression (Table 2), with a less steep decline in hazard following a score of 10 (Fig. 1). The associations were also very similar regardless of whether or not alcohol and drug use was included as covariates (Model 1a vs. Model 2a).

FIG. 1.

Associations between baseline depression/anxiety scores and hazard of ART initiation (log function) among 364 Chinese MSM. (a, c) Adjusted for age, intervention arm, study site, education, quality of life, living with someone, alcohol use, drug use, residency in Beijing, and HIV-related stigma; (b, d) adjusted for all covariates in (a,c) except alcohol use and drug use. ART, antiretroviral therapy; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Table 2.

Association Between Baseline Depression/Anxiety Scores and Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation Among 364 Chinese Men Who Have Sex with Men with Newly Diagnosed HIV Infections

| HR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression score | Model-1a | Model-1ba | Model-2a | Model-2ba |

| 3 vs. 0 | 1.82 (1.38–2.41) | 1.65 (1.25–2.16) | 1.81 (1.37–2.38) | 1.62 (1.23–2.13) |

| 9 vs. 0 | 3.11 (1.82–5.30) | 2.65 (1.56–4.50) | 3.10 (1.82–5.30) | 2.63 (1.55–4.46) |

| 13 vs. 0 | 2.53 (1.48–4.32) | 2.36 (1.38–4.03) | 2.60 (1.53–4.43) | 2.43 (1.43–4.14) |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety score | Model-1a | Model-1ba | Model-2a | Model-2ba |

| 3 vs. 0 | 1.58 (1.23–2.04) | 1.50 (1.17–1.94) | 1.57 (1.23–1.99) | 1.47 (1.14–1.89) |

| 9 vs. 0 | 2.67 (1.59–4.51) | 2.44 (1.44–4.13) | 2.65 (1.60–4.39) | 2.37 (1.40–4.02) |

| 13 vs. 0 | 2.49 (1.47–4.19) | 2.37 (1.40–4.02) | 2.54 (1.53–4.24) | 2.39 (1.41–4.04) |

The median scores for participants at normal, borderline, and likely depression/anxiety categories were 3, 9, and 13, respectively.

Model-1b and Model-2b were results of additional adjustment of CD4 count. By controlling baseline CD4 count, a potential mediator of depression/anxiety on ART initiation, we are estimating the direct effect of depression/anxiety (other than through CD4 count) on ART initiation.

HR, hazards ratio.

In our study population, depressed individuals had a lower CD4 count than participants with a normal depression score (median: 355 cells/μL vs. 407 cells/μL). Similarly, CD4 count was lower for anxious than nonanxious individuals (median: 362 vs. 407 cells/μL). The additional adjustment of CD4 count in the models of depression/anxiety led to smaller effect sizes (Table 2). However, the association between depression/anxiety and ART initiation remained strong.

Association between depression/anxiety categories and ART initiation

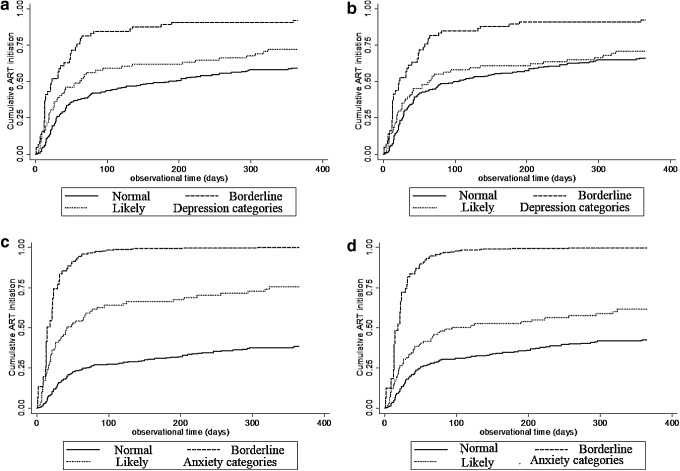

Depression and anxiety are frequently reported as categorical variables. Hence, we also present results with categorized depression/anxiety scores. Figure 2a and b shows the cumulative ART initiation rates over the observation time by different categories of depression. Participants with borderline depression were the most likely to initiate early ART, followed by those with likely depression and with no depression. The patterns for anxiety were similar to those of depression. Participants with borderline anxiety were more likely to initiate ART at an early time, followed by those with likely anxiety and those with no anxiety (Fig. 2c, d). Table 3 lists HRs of categorical depression/anxiety on ART initiation. Continuous and categorical measurements of depression and anxiety had similar patterns in terms of their effect on ART initiation.

FIG. 2.

Cumulative probability of ART initiation based on depression/anxiety categories among 364 Chinese MSM with newly diagnosed HIV infections. (a, c) Adjusted for age, study intervention, study site, education, quality of life, living with someone, alcohol use, drug use, residency in Beijing, and HIV-related stigma; (b, d) adjusted all covariates in (a, c) except alcohol use and drug use.

Table 3.

Association Between Categories of Depression and Anxiety and Antiretroviral Therapy Among 364 Chinese Men Who Have Sex with Men with Newly Diagnosed HIV Infections

| HR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression categories | Model-1a | Model-1ba | Model-2a | Model-2ba |

| Normal (0–7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Borderline depression (8–10) | 1.88 (1.32–2.67) | 1.61 (1.13–2.29) | 1.88 (1.32–2.67) | 1.61 (1.13–2.30) |

| Likely depression (11–21) | 1.30 (0.88–1.92) | 1.42 (0.97–2.09) | 1.38 (0.94–2.02) | 1.50 (1.02–2.19) |

| HR (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety categories | Model-1a | Model-1ba | Model-2a | Model-2bb |

| Normal (0–7) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Borderline anxiety (8–10) | 1.27 (0.88–1.82) | 1.28 (0.89–1.85) | 1.28 (0.89–1.84) | 1.30 (0.90–1.87) |

| Likely anxiety (11–21) | 1.52 (1.05–2.20) | 1.48 (1.03–2.14) | 1.57 (1.09–2.27) | 1.53 (1.06–2.19) |

Model-1b and Model-2b were results of additional adjustment of CD4 count. By controlling on baseline CD4 count, a mediator of depression/anxiety on ART initiation, we attained the direct effect of depression/anxiety.

The additional adjustment for CD4 count in models of categorized depression/anxiety did not show a straightforward decrease in HRs across categories (Table 3). In the categories of borderline depression and likely anxiety, there was a smaller effect after adjusting for CD4 count. However, there was an increased HR for likely depression and borderline anxiety.

Discussion

Mental health disorders, especially depression, have been reported to contribute to delays in ART initiation in PLWH.19,20,34,35 We conducted this study to test this hypothesis in Chinese MSM. However, we found a counterintuitive result that newly diagnosed Chinese MSM with current depression/anxiety were more likely to initiate ART, although it appeared that participants with more severe depression/anxiety may have been less likely to initiate ART early than participants with borderline depression/anxiety. Three other studies have also reported an increased uptake of ART among depressed individuals.23–25

A meta-analysis has shown that depression was associated with a decreased low level of CD4 counts, which is an important indicator for ART initiation.33 In our study population of newly diagnosed MSM, we did observe that depressed and/or anxious individuals had a lower CD4 count than participants without depression or anxiety. Additional adjustment of CD4 count showed that CD4 count alone was not sufficient to explain the earlier ART initiation among depressed/anxious participants in our study (Tables 2 and 3). Other explanations may be responsible for this counterintuitive result, including differences in populations in different studies, the impact of the policy change in China for free ART to all HIV-infected persons regardless of CD4 count, and differing severity of depression/anxiety in different studies.

MSM with newly diagnosed HIV infections in Beijing were a relatively well-educated population. They could learn about HIV and increase their awareness of HIV risk and care via multiple resources,36 including from their peers37 and from HIV intervention projects that target at them. Depression or anxiety may have been a reflection of their health concerns, nurturing their interest in ART. The Chinese government changed its policy for free ART during our study period; clinicians began to encourage newly diagnosed individuals to initiate ART regardless of CD4 count. Participants in this study received counseling on depression and anxiety from a trained psychologist, who referred participants for ART treatment as part of her counseling. Hence, both patients and practitioners may have influenced early ART in depressed and/or anxious persons.

The severity of depression/anxiety could be another explanation for this discrepancy compared to the literature. HADS performs well in depression/anxiety case finding, but it is not a robust tool to distinguish mild from major depression/anxiety.38 People with mild depression typically have relatively normal social functioning, while those with major depression have a significant impairment, such as isolation and avoidance of contact.39 Mildly depressed persons are also less likely to have the cognitive impairments that interfere with decision-making. Hence, individuals with mild depression could be more motivated to seek care than ones with major depression, especially if the mild depression is a functional response to concern about their recent HIV diagnosis. Anxiety might be a similar motivation. Since we measured depression/anxiety shortly after the HIV diagnosis, many participants screened as having depression/anxiety may have an understandable, transient reactive depression/anxiety. Hence, we speculate that our study results may be driven by the study design (HADS administered shortly after the HIV diagnosis) and by population characteristics (well-educated MSM).

In our study, 62% Chinese MSM with newly diagnosed HIV infections initiated ART during the 12 months of follow-up period. ART coverage in this newly diagnosed population was higher than that reported previously in China,5 perhaps due, in part, to the clinical trial nature of our study. In addition, we think that the liberalized policy of free ART treatment in China regardless of CD4 count may have contributed to the increased ART coverage in our study. Research has also shown that individuals with a higher education were more likely to initiate ART.17,40 In this study, over 70% of participants had a college education compared to less than 19% in the population of PLWH in China. Hence, higher education could be another contributor to this high ART coverage.

The comorbidity of depression and anxiety was common in our study population (32%). The depression score was also highly correlated with the anxiety score, precluding mutual adjustment in our analysis due to colinearity. From the viewpoint of mental health interventions, both depression and anxiety should be considered among MSM with newly diagnosed HIV infections.

Our study had several strengths. First, this study was part of an RCT, and we performed this analysis as a prospective cohort. Depression and anxiety were measured at baseline, and ART initiation could happen at any time after enrollment. Hence, we have a temporal relationship for the potential causality of depression/anxiety and ART initiation. Archived ART initiation in the national data set was used for our analysis instead of self-reported ART use. So, we can avoid reporting bias, loss to follow-up, and misclassification of our outcome. Our study population was homogenous, as they were all enrolled in a short time interval after HIV diagnosis. The study sample size was large enough to provide a high power to detect true, meaningful differences.

Our study also had several limitations. Our study recruited MSM from a single metropolitan city, and hence, we cannot generalize to the entire MSM population in China. Residual confounding might exist, as we used a proxy for social support for the purpose of confounding adjustment. Our measures of depression and anxiety after HIV diagnosis might not distinguish between reactions to learning of HIV-positive status versus mental disorders. We cannot estimate the effect of the change of policy of free ART treatment on our study, since it occurred during the time of study conduct.

Early ART initiation has multiple benefits for both individuals and for public health. We found that half of newly diagnosed MSM in our study initiated ART within 3 months of diagnosis. This suggests that it is possible to increase early ART initiation among newly diagnosed persons with interventions both at the policy and individual levels. Depression and anxiety showed unexpected positive effects in terms of ART initiation in our study, although this was attenuated in MSM with greater severity. Depression and anxiety measured after HIV diagnosis might be a reflection of health concern around being HIV positive. Hence, we need further studies with a representative sample to replicate our findings in other newly diagnosed populations. We also need to learn the impact of depression and/or anxiety, and their treatment, on retention in care and adherence to ART among newly diagnosed PLWH.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Yin Lu for her effort to manage the Multi-component HIV Intervention Packages for Chinese MSM project, and the staff at Beijing Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Xicheng CDC, Chaoyang CDC for their effort to make the data ready for analysis.

This study was supported by grants from the United States National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers R01AI094562 and R34AI091446.

H.-Z.Q., J.T., and S.H.V. worked together to propose this study. J.T. did the statistical analysis and drafted this article. A.M.K., B.E.S., H.L., H.-Z.Q., S.H.V., Y.R., and Y.S. provided valuable comments and suggestions, and revised this article.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. The Gap Report 2014

- 2.Dabaghzadeh F, Khalili H, Ghaeli P, Alimadadi A. Sleep quality and its correlates in HIV positive patients who are candidates for initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Iran J Psychiatry 2013;8:160–164 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beyrer C, Wirtz AL, Walker D, et al. The Global HIV Epidemics Among Men Who Have Sex with Men. The World Bank: Washington, D.C., 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2013 surveillance report. Surveillance Reports—HIV/AIDS 2015;25 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. China AIDS Response Progress Report 2015;2015

- 6.Zolopa A, Andersen J, Powderly W, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy reduces AIDS progression/death in individuals with acute opportunistic infections: A multicenter randomized strategy trial. PLoS One 2009;4:e5575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, et al. Effect of earlier initiation of antiretroviral treatment and increased treatment coverage on HIV-related mortality in China: A national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2011;11:516–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Horn T, Thompson MA. The state of engagement in HIV care in the United States: From cascade to continuum to control. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:1164–1171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uthman OA, Magidson JF, Safren SA, Nachega JB. Depression and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low-, middle- and high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2014;11:291–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg MB, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA. Mental health concerns of HIV-infected gay and bisexual men seeking mental health services: An observational study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2004;18:635–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivasubramanian M, Mimiaga MJ, Mayer KH, et al. Suicidality, clinical depression, and anxiety disorders are highly prevalent in men who have sex with men in Mumbai, India: Findings from a community-recruited sample. Psychol Health Med 2011;16:450–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoloff K, Joska JA, Feast D, et al. A description of common mental disorders in men who have sex with men (MSM) referred for assessment and intervention at an MSM clinic in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav 2013;17 Suppl 1:S77–S81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Sun X, Qian HZ, et al. Qualitative assessment of barriers and facilitators of access to hiv testing among men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:481–489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tao J, Ruan Y, Yin L, et al. Sex with women among men who have sex with men in China: Prevalence and sexual practices. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:524–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tao J, Wang L, Kipp AM, et al. Relationship of stigma and depression among newly HIV-diagnosed Chinese men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 2017;21:292–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chisholm D, Sweeny K, Sheehan P, et al. Scaling-up treatment of depression and anxiety: A global return on investment analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:415–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martinez P, Andia I, Emenyonu N, et al. Alcohol use, depressive symptoms and the receipt of antiretroviral therapy in southwest Uganda. AIDS Behav 2008;12:605–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pence BW, Ostermann J, Kumar V, Whetten K, Thielman N, Mugavero MJ. The influence of psychosocial characteristics and race/ethnicity on the use, duration, and success of antiretroviral therapy. JAIDS 2008;47:194–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De R, Bhandari S, Roy S, Bhowmik A, Rewari BB, Guha SK. Factors responsible for delayed enrollment for anti-retroviral treatment. J Nepal Health Res Counc 2013;11:194–197 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodness TM, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, et al. Depressive symptoms and antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation among HIV-infected Russian drinkers. AIDS Behav 2014;18:1085–1093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuniga JA, Yoo-Jeong M, Dai T, Guo Y, Waldrop-Valverde D. The role of depression in retention in care for persons living with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:34–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Osborn CY, Qian HZ, et al. Barriers and facilitators of linkage to and engagement in HIV care among HIV-positive men who have sex with men in China: A qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:70–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baez Feliciano DV, Gomez MA, Fernandez-Santos DM, Quintana R, Rios-Olivares E, Hunter-Mellado RF. Profile of Puerto Rican HIV/AIDS patients with early and non-early initiation of injection drug use. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(2 Suppl 2):S2-99-104 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Himelhoch S, Moore RD, Treisman G, Gebo KA. Does the presence of a current psychiatric disorder in AIDS patients affect the initiation of antiretroviral treatment and duration of therapy? JAIDS 2004;37:1457–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mijch A, Burgess P, Judd F, et al. Increased health care utilization and increased antiretroviral use in HIV-infected individuals with mental health disorders. HIV Med 2006;7:205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner BJ, Fleishman JA, Wenger N, et al. Effects of drug abuse and mental disorders on use and type of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:625–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang JX, Schwarzer R. Measuring optimistic self-beliefs: A Chinese adaptation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Psychologia 1995;38:174–181 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neilands TB, Steward WT, Choi K-H. Assessment of stigma towards homosexuality in China: A study of men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav 2008;37:838–844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steward WT, Herek GM, Ramakrishna J, et al. HIV-related stigma: Adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:1225–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernan MA, Hernandez-Diaz S, Werler MM, Mitchell AA. Causal knowledge as a prerequisite for confounding evaluation: An application to birth defects epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mackie CJ, Conrod P, Brady K. Depression and Substance Use. Drug Abuse and Addiction in Medical Illness. New York: Springer, 2012, pp. 275–283 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leserman J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med 2008;70:539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murray LK, Semrau K, McCurley E, et al. Barriers to acceptance and adherence of antiretroviral therapy in urban Zambian women: A qualitative study. AIDS Care 2009;21:78–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alemayehu M, Aregay A, Kalayu A, Yebyo H. HIV disclosure to sexual partner and associated factors among women attending ART clinic at Mekelle hospital, Northern Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2014;14:746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young SD, Rice E. Online social networking technologies, HIV knowledge, and sexual risk and testing behaviors among homeless youth. AIDS Behav 2011;15:253–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amirkhanian YA, Kelly JA, Kabakchieva E, et al. A randomized social network HIV prevention trial with young men who have sex with men in Russia and Bulgaria. AIDS 2005;19:1897–1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skodol AE, Schwartz S, Dohrenwend BP, Levav I, Shrout PE. Minor depression in a cohort of young adults in Israel. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:542–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cook JA, Grey DD, Burke-Miller JK, et al. Illicit drug use, depression and their association with highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive women. Drug Alcohol Depend 2007;89:74–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]