Abstract

A persistent theme in biomaterials research comprises of surface engineering and modification of bare metallic substrates for improved cellular response and biocompatibility. Graphene Oxide (GO), a derivative of graphene, has outstanding chemical and mechanical properties; its large surface to volume ratio, ease of surface modification and processing make GO an attractive coating material. GO-coatings have been extensively studied as biosensors. Further owing to its surface nano-architecture, GO-coated surfaces promote cell adhesion and growth, making it suitable for tissue engineering applications. The need to improve the long-term durability and therapeutic effectiveness of commercially available bare 316L stainless steel (SS) surfaces led us to adopt a polymer-free approach which is cost-effective and scalable. GO was immobilized on to 316L SS utilizing amide linkage, to generate a strongly adherent uniform coating with surface roughness. GO-coated 316 L SS surfaces showed increased hydrophilicity and biocompatibility with SHSY-5Y neuronal cells, which proliferated well and showed decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) expression. In contrast, cells did not adhere to bare uncoated 316L SS meshes nor maintain viability when cultured in the vicinity of bare meshes. Therefore the combination of the improved surface properties and biocompatibility implies that GO-coating can be utilized to overcome pertinent limitations of bare metallic 316L SS implant surfaces, especially SS neural electrodes. Also, the procedure for making GO-based protective coatings can be applied to numerous other implants where the development of such protective films is necessary.

Keywords: Graphene Oxide, Neuronal cells, Biocompatibility, Surface coating, Stainless Steel implants

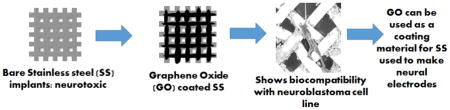

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Stainless steel (SS) alloys are often used as biomedical implants with applications in cardiovascular, orthopaedic and dentistry due to their superior mechanical properties. However the neurotoxicity of iron present in stainless steel makes it unsuitable as neuronal implants (1). The use of inert materials is of special importance for neural electrodes used for deep brain stimulation (DBS), useful in therapy of movement disorders including Parkinson’s disease (PD) (2). Acute misbalance of iron homeostasis in the brain has been linked to acute neuronal injury following cerebral ischemia (3). Free iron is known to catalyse the conversion of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide into hydroxyl radicals, which generate oxidative stress leading to subsequent apoptosis of neurons (3). Besides, bare metallic SS surfaces are often affected by biological corrosion and etching in vivo (2), releasing sub-lethal concentrations of metallic ions which could exacerbate the pro-inflammatory and fibrotic reactions (3, 4).

Therefore, surface modification is often used to mitigate such adverse physiological responses to SS implant materials (4). Various approaches to coat bare implant surfaces with biocompatible materials like diamond-like carbon (5), SiC (6), TiN (7), TiO2 (8), polymers (9) and biological moieties such as heparin (10) and dopamine (11) have been adopted for a variety of applications. But, each of these coating materials have inherent limitations of instability.

Specifically for neural implant electrodes, iridium oxide (12), multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWNT)-gold (13) (14) and conductive polymer coatings have been shown to improve electrochemical properties of electrodes (15). However, all implantable electrodes in Chronic Neural Interfaces (CNI) encounters a common problem of deteriorating in performance of recording capabilities over time because of tissue injury and adverse reactions due to the materials used for coating (16). To solve this issue, novel inert materials need to be explored as coating materials for neural electrodes.

As an alternative to SS, inert materials such as platinum (Pt) is used for making neural electrodes which is not cost effective (17). Further these Pt electrodes require nano-textured specialized coatings for optimized performance which further increase fabrication and processing cost (17). Therefore there is a need for a novel low-cost coating material which will confer biocompatibility, electrochemical performance, and sustainability for application in neural interface devices.

In an attempt to design a chemically and structurally stable robust electrode for chronic neural stimulation, Depan and Misra fabricated a hybrid of conducting polymer (poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):PEDOT) and carbon nanotubes (CNT). The PEDOT-CNT hybrid nanostructured composite coating on the SS electrodes provided biocompatibility, neuronal adhesion, outgrowth and high charge injection capacity (18). Others reported, poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(ε-caprolactone) (PEGPCL) hydrogel–poly(ε-caprolactone) neurotrophin-eluting hydrogel–electrospun fiber composite coatings for multi-electrode arrays which enhanced long-term device performance and function (19). However inclusion of a growth factor and polymer has its own challenges in terms of cost and manufacturing burden, and limited life-span of the growth factor incorporated. So a single component coating based on a polymer-free approach would be ideal for avoiding long-term toxicity associated with polymers (20). Thus in this study we aimed to develop graphene oxide (GO) as a novel polymer-free, biocompatible and strongly adherent coating on 316L SS implant surfaces for neuronal cell culture applications.

Graphene Oxide (GO) sheets are monolayers of carbon atoms that have oxygen atoms, -OH groups and –COOH groups attached forming dense and unique honeycomb structures (21) with applications in biomedical field (22–33). These functional groups enable GO to be readily dispersed in water (34). GO is popular amongst nanomaterial hybrids including gold nanoparticles on polyoxometalate/reduced graphene oxide used as biosensors (35, 36). Nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensing of neurological drugs utilizing a hybrid of bimetallic Platinum-Palladium (Pt/Pd) nanoparticles on 2-thiolbenzimidazole functionalized reduced graphene oxide provided a significantly greater electrochemical surface area compared to other conventional electrodes used (32). Other GO based sensors have also been used for similar reasons (37–43). Therefore, for GO-based coatings there is no extra step needed for introducing surface nano-texturing, which adds to ease of fabrication (17). Studies have shown that GO films allowed the effective proliferation of human and mammalian cells with limited or no cytotoxicity (29–31). Specifically, GO has been recently shown to promote the growth of neuronal cells (24, 31), human osteoblasts (44) and even osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (45). In our recently reported study, GO-coated surfaces significantly enhanced endothelial cell adhesion, proliferation and reduced ROS expression compared with bare implant surfaces (30). Such characteristics seem to indicate that GO may be an ideal candidate for coating implant surfaces along with the fact that GO is also chemically inert, electrically-conductive and durable (27, 46, 47). Recently, Cardenas et al. (48) described a new method for the growth of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) on 316L SS surfaces and its relevance for biomedical applications. According to the authors, electrochemical etching increased the concentration of metallic species on the surface and enabled the growth of rGO. Cell viability studies revealed that these rGO coatings did not have toxic effects on mammalian cells, making this material suitable for biomedical and biotechnological applications. Other researchers (49) reported a simple and green chemistry approach for the preparation of rGO nanosheets ranging from 20–70 nm suitable for biomedical applications.

These reports motivated us to further explore the feasibility of coating bare 316L SS surfaces with GO, and to determine the ability of these GO-coatings in enhancing the neuro-biocompatibility of existing 316L SS implant surfaces. In addition GO-coatings adhere strongly to underlying surfaces thereby forming an over–coating and a protective layer at the same time (50). This study will thus provide a new approach for future standardization, and risk assessment of coatings on metal alloys for medical applications.

GO was immobilized onto 316L SS surfaces using a carbodiimide reaction by surface treatment with g-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) (4). GO coated 316L SS surfaces were prepared, characterized and used to culture SHSY-5Y neuroblastoma cells (51) to assess the overall biocompatibility of the modified substrate. Further, this method of GO-coating can be adapted to other metallic implants where the development of such protective and biocompatible coatings is essential (47, 52). Results from this study will inform and guide further detailed studies to fabricate, characterize and optimize the behaviour of GO-coated SS neural electrodes.

Experimental

Materials

Graphite flakes (~150 μm), APTES (99%), 1-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-1′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC), N-Hydroxysuccinimide (98%) (NHS), Atto 495 NHS ester, was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). 0.25% Trypsin/EDTA and Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 1X) was obtained from Sigma. 316L SS wire cloth mesh (200 x 200 Super-Corrosion Resistant type 316L SS Wire Cloth, 0.0016″ Wire Diameter, 46% open area, McMaster-Carr, Los Angeles, CA, USA) was used to mimic surgical grade 316L SS implant surfaces. Solid strips of the same material (316L SS, thickness 0.015″, width 1″ and length 24″; McMaster-Carr) were used for contact angle, nanoindentation and film thickness measurements.

Methods

Preparation and characterization of GO

GO was prepared by a modified Hummer’s method by the oxidation of graphite as done previously (34, 53, 54). Briefly, a 50 ml (9:1) mixture of sulphuric acid/ phosphoric acid (H2SO4/H3PO4) was added to a mixture of 2 g of graphite flakes and 6 g of potassium permanganate (KMnO4). The reaction mixture was then heated to 50°C with stirring for 12 hr, and consecutively cooled and poured onto ice. The resultant solution was finally treated with 10 ml of 30% H2O2 to terminate the reaction. The mixture was then sifted and filtered; it was later centrifuged and the supernatant was decanted away. The remaining solid GO was washed consecutively with distilled water, 30% H2O2, and ethanol (C2H6O); for each wash, the mixture was again sifted and filtered. After multiple washes, the remaining material was coagulated with ether (C2H5)2O and the resulting suspension was filtered. The final solid product was freeze-dried under vacuum overnight. All chemicals used in the in-house synthesis of GO were procured from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA.

FTIR analysis

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was used to reveal information about the molecular structure of GO prepared in-house, in comparison with published literature. Attenuated total reflectance (ATR)-FTIR spectra of a representative GO sample was acquired using a Perkin-Elmer, Spectrum 100, Universal ATR Sampling Accessory within the range of 650–3650 cm−1 in transmittance mode (55). Spectral manipulations were performed using the spectral analysis software GRAMS/32 (Galactic Industries Corp., Salem, NH, USA). External reflection FTIR was recorded on a Specac grazing angle accessory using an s-polarized beam at an angle of incidence of 40° and a mercury cadmium telluride (MCT/A) detector. A piranha-treated silicon wafer was used as the background.

Stainless Steel mesh treatment prior to GO immobilization

Surface modification was performed on the 316L SS meshes as follows. The mesh was cut into 2 cm × 1 cm pieces, and sonicated in acetone for 20 min, followed by air drying and consecutive heating (250°C, 1 hr). The pristine cleaned 316L SS meshes were denoted as NHT (no heat treatment), and the heated ones as HT (heat treated) respectively.

316L SS silanization with APTES

For modifying the 316L SS surfaces to promote GO immobilization, it was necessary to covalently introduce a layer of functional silane groups onto the surfaces. To enable this reaction, all samples were submerged in a 10% v/v solution of APTES/Xylene (Sigma) with continuous stirring for 24 hr to facilitate the carboxyl (-COOH) groups of the GO to covalently bond to the amine (-NH2) groups.

GO immobilization and retention

Atto 495 NHS-ester dye solution was made by adding 5 μl of the dye solution in DMSO (2 mg/ml) to 95 μl of bicarbonate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.3). 100 μl of this prepared solution was laid onto each mesh treated with APTES, to confirm the attachment of amine groups and incubated at room temp for upto 2 hr after which they were imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ti, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY, USA). Fluorescence and bright field images were acquired and later merged with identical parameters using ImageJ.

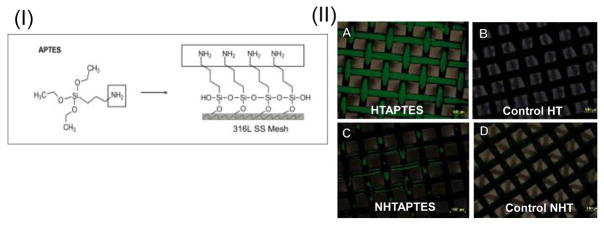

Upon confirmation of the amine groups on the 316L SS meshes (Figure 1(II)), a saturated solution of 2 mg/ml of GO/Milli-Q water was made to coat all samples by eliciting a carbodiimide reaction using the crosslinking agents EDC and NHS (56). Samples were submerged in 10 ml of the GO/Milli-Q water solution, 0.8 grams of EDC and 1.2 mg of NHS were added at room temperature (25°C) with vigorous stirring for 24 hr. The GO-coated meshes were then heated in the oven (250°C, 1 hr) to stabilize and bind the GO coating with underlying substrate. All chemicals used in this step were procured from Sigma.

Figure 1.

(I) Schematic for deposition of NH2 groups on 316L SS meshes. (II) Confirmation of NH2 groups on the 316L SS meshes.

Shown in panel (A–D) are Atto 495 dyed 316L SS meshes, scale bar = 100 μm. In (A) the meshes were heat and APTES treated (denoted as HTAPTES); (C) the pristine cleaned 316L SS meshes were not heat treated but treated with APTES (denoted as NHTAPTES). Controls for all these treatment are shown in (B) and (D).

Characterization of the GO-coating

XRD for confirmation of GO-coating deposition

To investigate the efficacy of the coating and the phase assemblage of the GO and the APTES coated 316L SS strips, samples were examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD). For the XRD, the samples were scanned using an X-ray of Cu source (CuKα, wavelength: 1.54056 A) for a 2 theta value ranging from 5° to 90° at a scanning rate of 2°/min with an increment (step size) of 0.05°. The XRD machine (D8 Discover, Bruker’s diffractometer, Germany) was operated in locked-coupled mode at 40 kV voltage and 40 mA current.

SEM analysis for probing morphology of GO coated surfaces

To image the morphology of the deposited GO-film, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used. Samples were visualized using SEM (S-4800, Hitachi, Japan) at voltages of 5 KV.

Measurement of contact angle

For measuring contact angles, GO was deposited onto 316L SS strips using similar immobilization procedures as used for the meshes. Water contact angles of the GO-coated surfaces were measured at room temperature and humidity using a standard goniometer (Model 250-F4, Ramé-hart, Succasunna, NJ, USA) based on the sessile drop method. For each value reported, the mean and standard deviation of at least 10 measurements from the same sample surface were recorded. For each case, two representative samples were prepared and analysed.

Estimation of coating thickness

For measuring GO-coating thickness, GO was immobilized onto 316L SS strips using similar procedures as used for the 316L SS meshes. Cross section of the GO-coated samples were visualized using SEM (Hitachi TM-1000 Tabletop Microscope, Tokyo, Japan) at 1000× to 5000× magnification. Acquired images were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH) to calculate average thickness of the deposited GO-coatings.

Nanoindentation for mechanical analysis

A dynamic nanoindentor (Hysitron TI 750H Ubi nanomechanical test instrument, Hysitron Inc. MN, USA) with a diamond tip, of diameter 200 nm, was used for the indentation of the GO coating. Furthermore, hardness and elastic modulus were calculated using area under the loading and unloading curve i.e. plastic and elastic work of the indentation, respectively. The value of total work of indentation (a sum of plastic and elastic work) was substituted in the following equation to calculate the hardness of the GO coating (57).

| (1) |

where, k is a constant equal to 0.0408 (for a three sided Berkovich pyramidal indenter). Pm and Wt, are the maximum load and total work of indentation.

The standard method to measure the elastic modulus of the coating is by analysis of the unloading curve. This is due to the fact that even for a plastic deformation during loading, the initial part of the unloading curve exhibits the elastic nature of the material. Therefore, slope of the initial part of unloading curve can be used to calculate the elastic modulus of the material using the following equation (58, 59).

| (2) |

where, Er, E, and Ei are the reduced elastic modulus, elastic modulus of the substrate i.e. graphene oxide coating, and elastic modulus of a diamond indenter (= 1141 GPa) respectively (58). ν and νi, are the Poisson ratio of the graphene oxide (= 0.165 (60)) and the indenter (0.07 (58)).

The reduced elastic modulus can be calculated using the following equation (58, 61),

| (3) |

where, Smax and A are the slopes of the unloading curve at the starting point i.e. at the point of maximum loading, and the projected area of indentation respectively. The projected area of indentation is defined in terms of contact depth, hc and can be expressed as (58),

| (4) |

where, εis a constant that depends on the geometry of the indenter and for a sharp Berkovich indenter, this value is 0.75 (61). Therefore, for the present case of nano-indentation, equation 4 was rewritten as,

| (5) |

It is already known from the load-displacement curve that hc < hmax (61). The contact area of the indentation is a function of the contact depth (hc) i.e. A = A(hc) (58) and for a perfectly sharp Berkovich indenter, .

Therefore, A in equation 3 was replaced with hc to calculate the elastic modulus of the coating “E” using equation 2.

Modified equation 3 shown in 6 was used to estimate Elastic Modulus of the deposited GO coatings onto SS substrates.

| (6) |

Cell culture on GO coated surfaces

Adhesion and proliferation of SHSY-5Y neuroblastoma cells atop GO-coated surfaces

In preparation for cell culture, the precut meshes including bare, APTES-treated and GO-coated were washed first in 70% ethanol, followed by PBS (1X) and air dried under a sterile laminar flow hood. After drying, the samples were transferred to wells (one mesh/ well) in a 24 well plate (Corning, NY, USA). SHSY-5Y cells, a generous gift from Dr. Mahesh Narayan from Chemistry department at UTEP, were seeded atop these meshes following procedures described. SHSY-5Y is used as a model of in vitro neurodegenerative disease studies because it has biochemical properties of human neurons in vivo (51, 62). Further, since these cells are tumour derived, they have the ability to continuously grow and divide (51). The cells can be differentiated to provide mature neuron-like phenotype (51).

SHSY-5Y cells were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) (1:1; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% heat inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100U/ml penicillin and 100 mg/ml streptomycin all from Gibco. Prior to the mesh experiment, the cells were cultured and stabilized for several passages at 37°C, 5% CO2. Confluent T-25 flasks of SHSY-5Y cells were trypsinized and cells extracted for further experiments.

Pre-cleaned bare, APTES treated and GO-coated 316L SS meshes were further cut into 8 mm × 8 mm (n=3 for each case) and placed into the media per well of a 24 well plate. Then the cells were added to the respective wells at a density of 10,000 cells/well with 2 mL of media per well. The seeded cells on meshes in wells were then incubated (37°C, 5% CO2) for a period of 72 hr.

After 72 hr, the cells at the bottom of the wells were stained using DAPI (Vector labs, Burlingame, CA, USA) and Ethidium homodimer-1 (Dead cell stain, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope (ZEISS Axio Observer, ZEISS, NY, USA).

Cell proliferation on the meshes was estimated as described. Meshes seeded with cells were carefully transferred to unused wells, gently rinsed with PBS, overlaid with 1 mL of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA per well and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Extracted cells were pelleted by centrifugation, and counted using a hemocytometer throughout the entire culture period after 72 hr of culture following published procedures (63). Similarly cells that adhered to the plastic wells for the respective mesh samples were also trypsin-extracted and estimated after 72 hr of culture. Mean values obtained by averaging values from at least 3 samples per case were reported for cells adhered onto plastic wells and mesh surfaces respectively for each case, in comparison to controls (plastic only). All cell culture experiments were repeated twice (n = 3 for each experiment).

En-face images of the meshes seeded with cells were acquired using SEM following published procedures to confirm cell adhesion onto the meshes (64). For sample preparation, cells on meshes were histologically fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma, 4°C, overnight), and then dried under a constant laminar air-flow in a fume hood. Dried samples were coated with gold (2–3 min) in a sputter coater (Quorum EMS150R ES, Quorum Technologies Ltd., UK) and visualized using SEM (Hitachi TM-1000 Tabletop Microscope) at 1000× to 5000× magnification.

ROS detection and quantification

In order to establish GO’s role in modulating inflammatory responses if any, reactive oxygen species (ROS) expression in SHSY-5Y cells cultured atop GO-coated meshes was analyzed using immunofluorescence following published procedures (65). Levels of ROS in SHSY-5Y cultured in the vicinity of GO-coated surfaces were assessed using conversion of non-fluorescent dihydroethidium (DHE:Sigma) to fluorescent ethidium bromide. Cells cultured in wells along with bare uncoated 316L SS (controls) and GO-coated meshes were incubated with DHE (10 μM) for 15 min at 37°C under dark conditions and imaged within 5–7 min. Cells cultured in wells that did not contain any meshes served as negative controls. After 15 min of incubation, cells were visualized using an inverted fluorescence microscope (ZEISS Axio Observer).

Statistical analysis

All samples were present in triplicate unless otherwise mentioned. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Student’s t-test was performed to determine if the averages of any two sample datasets compared were significantly different. p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant wherever reported.

Results and Discussion

Silanization of bare 316L SS surfaces

To modify the inorganic surface of the 316L SS mesh to promote GO immobilization, the initial reaction that occurred on the 316L SS mesh was the –Si-O-Si of the silane coupling agent (APTES) bonding with –OH groups in GO on the mesh’s surface (Figure 1(I)) (56, 66).

Confirmation of NH2 group immobilization

Atto 495 NHS-ester die treatment confirmed the presence of amine groups on the treated surfaces. The mesh samples which were heat treated reacted the most with APTES compared to non-heat treated controls. The heat-treated samples retained the maximum amount of NH2 groups when confirmed visually, compared to controls (Figure 1(II)). Therefore, heat treatment was used as an optimized prior treatment for 316L SS meshes that were then reacted with APTES to bind NH2 groups. Amine (NH2) groups when immobilized onto metallic surfaces can retard the corrosion rate of coated surfaces (67). This is because amine acts as protonated species that can accept electrons from iron atoms (68). This allows the free sites created during the corrosion process to be filled by the adsorption of amine groups leading to the formation of a protective film which prevents the further corrosion of the 316L SS in acidic environments (69, 70).

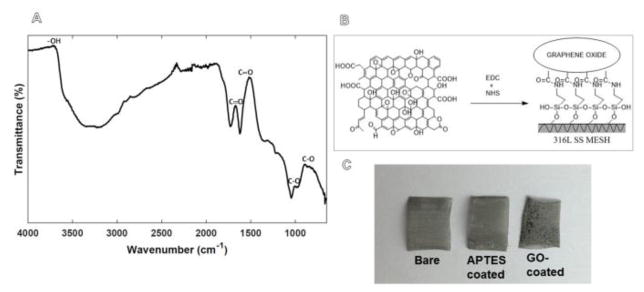

Confirmation of GO immobilization

FTIR spectra analysis revealed the structure and functional groups of the in-house synthesized GO (71, 72) (Figure 2A). The spectrum showed the presence of C=O stretching vibration centred at 1728 cm−1, graphene sheet aromatic C=C stretching vibration at 1622 cm−1, broad O–H stretching at 3400 cm−1, C-OH bending at 1368 cm−1, C-O stretching at 1045 cm−1 and C–OH stretching at 1222 cm−1. The presentation of oxygen-containing functional groups, such as –COOH, –OH, epoxide, and alcoxide confirmed that the synthesized compound was GO in consistence with other published evidences (34, 53, 66). It is known that the –COOH and -OH groups in GO are acidic in aqueous medium, due to the electron-donor property of double bonds in benzene rings. However in this case the –COOH and –OH groups reacted completely with the –NH2 groups present on the 316L SS surface from the APTES treatment, leading to GO-immobilization. Therefore, these GO-coatings are not expected to be thrombogenic when developed for in vivo use (47).

Figure 2.

Shown in (A) is a representative FTIR spectrum of GO prepared in-house. The chemical crosslinking scheme for GO adhesion is depicted in (B). GO coating was visually confirmed as shown in (C) in comparison with uncoated and APTES treated 316L SS meshes. Shown in (B) is the schematic for GO-immobilization onto 316 L SS meshes and in (C) are pristine 316 SS meshes (left), APTES-coated meshes (middle) and GO-coated meshes (right).

A saturated aqueous solution of 2 mg/ml GO was used to coat all 316L SS samples following scheme outlined in Figure 2B. GO deposition was visually confirmed on the 316L SS meshes compared to non-coated meshes (Figure 2C). GO-coated meshes were then washed, to remove the unreacted GO and then used for further experiments.

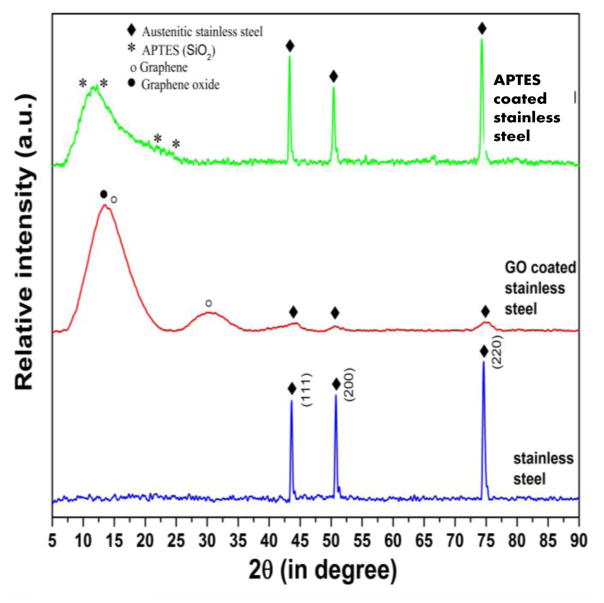

Confirmation of the GO-coating

Three samples in each category including bare (uncoated) 316L SS, GO-coated 316L SS, and APTES coated 316L SS were analysed using XRD, from which one representative spectrum from each case was depicted (Figure 3). The XRD spectra of bare 316L SS revealed the presence of diffraction peaks matching with the austenite phase, with three major diffraction peaks corresponding to 111, 200, and 220. No other phase was identified in the detection limit of the XRD (Figure 3). The XRD spectra of GO coated samples confirmed the presence of signatory diffraction peaks of GO with very low-intensity diffraction peaks corresponding to substrate material (316L SS). In addition to this, peaks corresponding to reduced GO were also found. The XRD of APTES coated samples confirmed the presence of diffraction peaks corresponding to SiO2 (ICDD pdf # 890735). In this case, the highest intensity diffraction peaks were of the stainless steel substrate. However, no other phase than SiO2 and stainless steel were noted.

Figure 3.

XRD of bare stainless steel, GO coated stainless steel, APTES coated stainless steel substrates, showing the presence of GO and APTES on the substrate surface.

In both cases, for GO- and APTES-coated 316L SS (ICDD pdf # 033-0397) samples, the absence of any other diffraction peaks except the diffraction peaks of the base material and coating confirmed the purity and efficacy of the coating and coating-method, respectively.

In addition to GO, the presence of reduced GO could be related to the in-house synthesis of GO which involved the oxidation of graphite (71, 72). In the case of GO coating, the peak corresponding to GO was of highest intensity among the other phases. This confirmed GO as the most abundant phase in the stable coating of GO on the 316L SS substrates. However, in the case of APTES coated samples, the coating was not very uniform, which was confirmed by the presence of high intensity diffraction peaks of austenite phase of substrate 316L SS. To fix this issue, pristine cleaned 316L SS samples will be polished, surface smoothness confirmed using SEM and then APTES treated in future to promote deposition of a uniform coating of APTES.

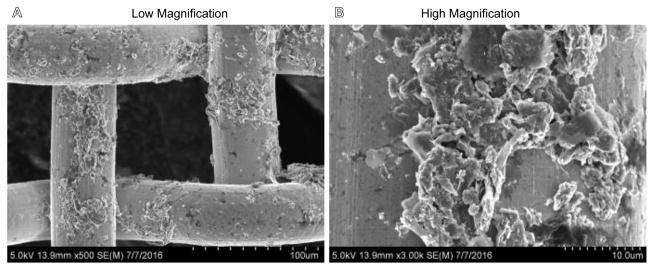

Morphology of the GO coating

SEM revealed that though the GO-coating was retained all over the 316L SS mesh surface, it seemed non-homogenous (Figure 4). The junctions of the meshes seemingly showed greater amounts of GO deposited compared to struts possibly due to higher surface energies of the materials at the junctions (Figure 4). We attempted to graft GO onto mesh surfaces simply by stir-coating, and did not employ any special means to make the coating uniform. In future, we will employ means to make the GO-coating uniform on the 316L SS surfaces using electrophoretic deposition or spin coating. Further polishing the 316L SS surfaces prior to coating will promote uniform APTES coating which will in turn facilitate uniform homogenous GO coating.

Figure 4.

Representative SEM images of GO-coated meshes at various magnifications.

Nevertheless, the GO-coating appeared to possess surface-roughness on a nanoscale (Figure 4, Figure 5A: Top panel, right most). No such nano-scale roughness was noted in meshes coated with APTES or in non-coated control 316L SS substrates (Figure 5A, Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 5.

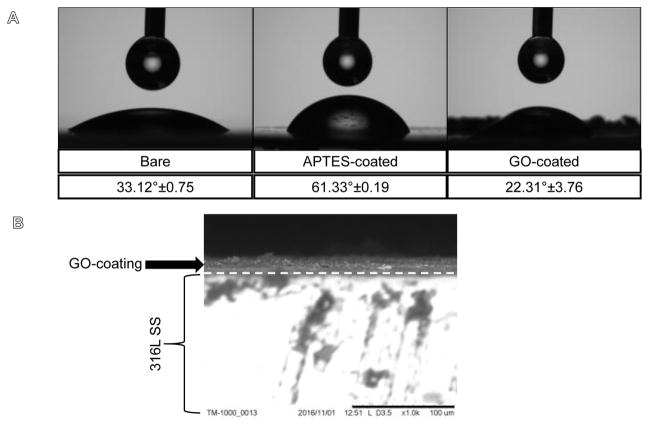

Shown in (A) are the representative images and the results of contact angle investigations. GO-coated surfaces maintained hydrophilicity as shown above. (B) Representative SEM image of GO-coating on 316L SS strip.

Surface hydrophilicity is retained after GO-coating

The surface hydrophilicity retained by the GO-coating was revealed from contact angle investigations (Figure 5A). The absorbed GO-coating decreased the contact angle to 22.31°±3.76 in comparison to bare untreated samples (33.12°±0.75) (p=0.009). Silanized APTES-coated substrate showed an average contact angle of 61.33°±0.19. Therefore the GO-coating conferred hydrophilicity to the coated 316L SS substrates probably due to the nano-topographic roughness (Figure 5A).

GO coating thickness

For the samples analysed using SEM (Figure 5B), the average thickness of the GO-coating was 11.24 ± 1.23 μm. Earlier studies have shown that a single layer of GO sheet is 0.52 nm in thickness (73). So it was concluded that a multi-layered coating of GO was deposited due to APTES treatment and GO immobilization on the 316L SS meshes. Others investigating multi-layered GO films have found these coatings to be impermeable to gases, liquids and aggressive chemicals thereby protecting the underlying surface from interfacing with corrosive environments (46).

Hardness and Modulus of elasticity of the GO-coating

Inside complex in vivo environments, applied biomaterial coatings usually play a role in the targeted performance of a biomaterial, such as bioactivity (74). Therefore, apart from biological properties, the reliability of such biomaterial coatings can be affected by its mechanical properties, such as hardness and elastic modulus. A technique such as nanoindentation can be used to measure the mechanical properties of applied coatings, including hardness and elastic modulus by deforming them on a very small scale. For all GO-coated samples analysed, the average value of hardness was 19.950 ± 0.248 GPa and the average value of elastic modulus was 570.560 ± 25.659 GPa.

The measured values of hardness and elastic modulus of GO coating were higher than the hardness and elastic modulus of other common implant coatings on 316L SS (71, 72, 75). Substrate hardness plays an important role in the determination of the wear and tear properties of a material and generally, a higher hardness indicates a lower wear rate (76). Therefore, on the basis of nanoindentation results, it is expected that the GO-coating will exhibit significantly lower coefficient of friction and lower wear rate as well, when implanted in vivo. Besides, studies have also shown that substrate stiffness, a property related to hardness and elastic modulus, is an important growth cue for neuronal outgrowth and differentiation (77). Stiffer substrates with enhanced elastic modulus increased cultured neuronal network activity atop these substrates (77). Therefore the GO-coating should be beneficial for neuronal outgrowth, and may even be beneficial in studies to probe the behavior of diseased or damaged Parkinson’s neurons (19).

Biocompatibility of the GO-coating

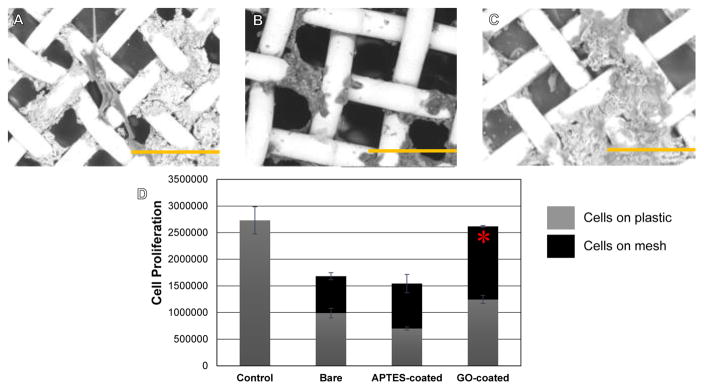

To determine the overall biocompatibility of the GO-coatings, SHSY-5Y cells were cultured atop these substrates. From other published studies using these cell types, it is already known that GO is non-cytotoxic and promotes cell adhesion and differentiation in SHSY-5Y cells (24). In line with these published reports, it was seen that SHSY-5Y cells adhered well onto GO-coated surfaces (Figure 6 A, B, C), to a greater extent than on bare or APTES coated 316L SS surfaces (Figure 6D). Cells on the GO-coated surfaces appeared to express a mature neuronal morphology and phenotype (Figure 6A). Cells attached and grew on both the plastic wells and the meshes (Figure 6D), however total number of proliferating cells at the end of culture was much lesser in wells that contained bare and APTES-coated meshes, in comparison to GO-coated meshes or plastic well controls (Figure 6D). When compared amongst culture groups of cells seeded on meshes in wells, cells adhered and proliferated significantly more on GO-coated meshes in comparison with bare (p=0.001) and APTES-coated (p=0.006) meshes (Figure 6D). These results implied that GO-coatings enhanced SHSY-5Y cell adhesion and proliferation thereby improving the functionality and behaviour of these cells when seeded on GO.

Figure 6.

Representative SEM images of SH5YSY cells grown atop GO-coated meshes in (A) (B) and (C). Depicted scale bars are a 100 μm. (D) Confirmation of cell proliferation on GO-coated meshes. Significantly greater no. of viable proliferating cells were detected on GO-coated meshes after 72 hr of culture compared with bare and APTES-coated meshes.

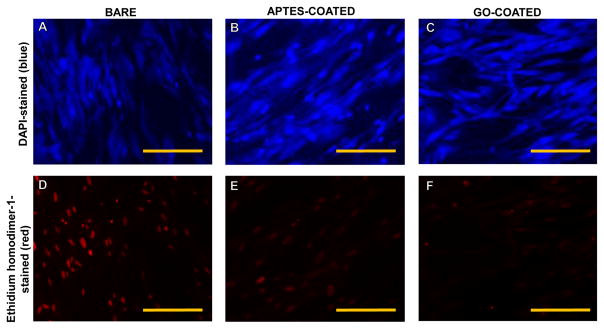

On the other hand, cells that were cultured in the vicinity of the meshes including bare, APTES- and GO-coated showed maximum number of dead cells in wells that contained the bare non coated meshes, in comparison to the other cases (Figure 7). This result further supported the fact that GO was not cytotoxic.

Figure 7.

Cells cultured in the vicinity of bare-316L SS (A and D), APTES-coated (B and E) and GO-coated samples (C and F) stained using DAPI (top panel) and a dead cell stain, Ethidium homodimer-1 (bottom panel) depicted in representative images. Maximum no. of cells appeared dead when cultured in the vicinity of bare-316L SS samples but not the other cases. Scale bar is 100 μm.

SHSY-5Y cells cultured in the vicinity of GO-coated meshes exhibited lesser number of cells that showed less intense red DHE fluorescence, compared to cells cultured on pristine 316L SS meshes (Supplementary Figure 2). Therefore, culturing cells on GO-coated 316L SS meshes did not activate signalling pathways that lead to ROS activation and cellular damage. In a study by Min Lv et al. (24), SHSY-5Y cells cultured atop GO nanosheets showed no cytotoxicity associated with the GO, which further enhanced the differentiation of SHSY-5Y induced-retinoic acid (RA) by increasing neurite extension length and the expression of neuronal marker MAP2. Results from this study and others (31) strongly imply a role of GO-coatings as applications for neurodegenerative diseases. Further, we have shown that neuronal cell culture atop GO actually mediated ROS expression, which could lead to its application as coating material for neural implant electrodes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, GO coated surfaces did not exhibit any significant in vitro toxicity for SHSY-5Y cells and reduced their ROS expression, confirming their biocompatibility. Further, GO coatings were found to be stable, non-reactive and added surface roughness to the implant surfaces, which permitted cell adhesion, spreading and proliferation, without inclusion of any additional neuronal growth factors (19). All of these characteristics make GO suitable for 316L SS biomedical implants and devices. This study significantly advanced the existing knowledge on the biological properties of GO-coating and its possible applications in biomedical field.

The procedure employed for making GO-coatings in this study is fairly facile, inexpensive and less time consuming. In addition, our technique for making GO-coatings is aqueous based, easily scalable, cost effective and allows room temperature fabrication. The finding of these results can be extended to other studies wherein such hydrophilic and corrosion defiant GO-coatings also have immense potential as a protective shield for oxidation prone active metal surfaces.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

In this study, GO was immobilized on to 316L SS utilizing carbodiimide chemistry, to generate a strongly adherent uniform nano coating with texture. GO-modified surfaces showed increased hydrophilicity and biocompatibility with SH5YSY cells cultured atop these surfaces. Further, cells cultured on GO-coated surfaced proliferated and aligned well with the underlying structure. Therefore the combination of the improved surface properties and improvement in cell viability implies that GO-coating can be utilized to overcome pertinent limitation of bare metallic 316L SS implant surfaces.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals at UTEP: Shweta Anilkumar, Swadipta Roy, Aditya Mishra, Alexandra Alcantara Guardado, Lois. M. Mendez, Mahesh Narayan, M.A.I. Shuvo, Ricardo Martinez, Yirong Lin, Deidra Hodges, Luis C. Echegoyen and J.C. Noveron for technical support and editing with the manuscript. BJ acknowledges NIH BUILD Pilot grant 8UL1GM118970-02, NIH 1 SC2 HL134642-01, COE Interdisciplinary Research Funds (IRS), University Research Initiative (URI) and Start-up funds at UTEP. NT acknowledges the Anita Mochen Loya Fellowship at UTEP COE.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gimsa J, Habel B, Schreiber U, van Rienen U, Strauss U, Gimsa U. Choosing electrodes for deep brain stimulation experiments–electrochemical considerations. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2005;142(2):251–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manivasagam G, Dhinasekaran D, Rajamanickam A. Biomedical implants: Corrosion and its prevention-a review. Recent Patents on Corrosion Science. 2010;2(1):40–54. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selim MH, Ratan RR. The role of iron neurotoxicity in ischemic stroke. Ageing Research Reviews. 2004;3(3):345–53. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshioka T, Tsuru K, Hayakawa S, Osaka A. Preparation of alginic acid layers on stainless-steel substrates for biomedical applications. Biomaterials. 2003;24(17):2889–94. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grill A. Diamond-like carbon coatings as biocompatible materials—an overview. Diamond and related materials. 2003;12(2):166–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nurdin N, Francois P, Mugnier Y, Krumeich J, Moret M, Aronsson B, et al. Haemocompatibility evaluation of DLC-and SiC-coated surfaces. European Cells and Materials. 2003;5:17–28. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v005a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braic M, Balaceanu M, Braic V, Vladescu A, Pavelescu G, Albulescu M. Synthesis and characterization of TiN, TiAIN and TiN/TiAIN biocompatible coatings. Surface and Coatings Technology. 2005;200(1):1014–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kommireddy DS, Patel AA, Shutava TG, Mills DK, Lvov YM. Layer-by-layer assembly of TiO2 nanoparticles for stable hydrophilic biocompatible coatings. Journal of nanoscience and nanotechnology. 2005;5(7):1081–7. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2005.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Yuan L, Song W, Wu Z, Li D. Biocompatible polymer materials: role of protein–surface interactions. Progress in Polymer Science. 2008;33(11):1059–87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan W, Kapoor M, Kumar N. Covalent attachment of proteins to functionalized polypyrrole-coated metallic surfaces for improved biocompatibility. Acta Biomaterialia. 2007;3(4):541–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joddar B, Albayrak A, Kang J, Nishihara M, Abe H, Ito Y. Sustained delivery of siRNA from dopamine-coated stainless steel surfaces. Acta biomaterialia. 2013;9(5):6753–61. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cogan SF, Guzelian AA, Agnew WF, Yuen TG, McCreery DB. Over-pulsing degrades activated iridium oxide films used for intracortical neural stimulation. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2004;137(2):141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keefer EW, Botterman BR, Romero MI, Rossi AF, Gross GW. Carbon nanotube coating improves neuronal recordings. Nature nanotechnology. 2008;3(7):434–9. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minnikanti S, Skeath P, Peixoto N. Electrochemical characterization of multi-walled carbon nanotube coated electrodes for biological applications. Carbon. 2009;47(3):884–93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abidian MR, Martin DC. Experimental and theoretical characterization of implantable neural microelectrodes modified with conducting polymer nanotubes. Biomaterials. 2008;29(9):1273–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lind G, Linsmeier CE, Thelin J, Schouenborg J. Gelatine-embedded electrodes—a novel biocompatible vehicle allowing implantation of highly flexible microelectrodes. Journal of neural engineering. 2010;7(4):046005. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/7/4/046005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah KG, Tolosa VM, Tooker AC, Felix SH, Pannu SS, editors. Improved chronic neural stimulation using high surface area platinum electrodes. 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2013 3–7 July; Osaka, Japan. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Depan D, Misra R. The development, characterization, and cellular response of a novel electroactive nanostructured composite for electrical stimulation of neural cells. Biomaterials Science. 2014;2(12):1727–39. doi: 10.1039/c4bm00168k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han N, Rao SS, Johnson J, Parikh KS, Bradley PA, Lannutti JJ, et al. Hydrogel–electrospun fiber mat composite coatings for neural prostheses. Frontiers in neuroengineering. 2011;4(2):8. doi: 10.3389/fneng.2011.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McConnell GC, Rees HD, Levey AI, Gutekunst C-A, Gross RE, Bellamkonda RV. Implanted neural electrodes cause chronic, local inflammation that is correlated with local neurodegeneration. Journal of neural engineering. 2009;6(5):056003. doi: 10.1088/1741-2560/6/5/056003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu Y, Murali S, Cai W, Li X, Suk JW, Potts JR, et al. Graphene and graphene oxide: synthesis, properties, and applications. Advanced materials. 2010;22(35):3906–24. doi: 10.1002/adma.201001068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryoo S-R, Kim Y-K, Kim M-H, Min D-H. Behaviors of NIH-3T3 fibroblasts on graphene/carbon nanotubes: proliferation, focal adhesion, and gene transfection studies. Acs Nano. 2010;4(11):6587–98. doi: 10.1021/nn1018279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruiz ON, Fernando KS, Wang B, Brown NA, Luo PG, McNamara ND, et al. Graphene oxide: a nonspecific enhancer of cellular growth. ACS nano. 2011;5(10):8100–7. doi: 10.1021/nn202699t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lv M, Zhang Y, Liang L, Wei M, Hu W, Li X, et al. Effect of graphene oxide on undifferentiated and retinoic acid-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells line. Nanoscale. 2012;4(13):3861–6. doi: 10.1039/c2nr30407d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu CH, Yang HH, Zhu CL, Chen X, Chen GN. A graphene platform for sensing biomolecules. Angewandte Chemie. 2009;121(26):4879–81. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim J, Choi KS, Kim Y, Lim KT, Seonwoo H, Park Y, et al. Bioactive effects of graphene oxide cell culture substratum on structure and function of human adipose-derived stem cells. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2013;101(12):3520–30. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore KJ, Wallace GG, Chen H, Muller MB, Li D. Mechanically strong, electrically conductive, and biocompatible graphene. Advanced materials. 2008;20(18):3557–61. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung C, Kim Y-K, Shin D, Ryoo S-R, Hong BH, Min D-H. Biomedical applications of graphene and graphene oxide. Accounts of chemical research. 2013;46(10):2211–24. doi: 10.1021/ar300159f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang Y, Yang S-T, Liu J-H, Dong E, Wang Y, Cao A, et al. In vitro toxicity evaluation of graphene oxide on A549 cells. Toxicology Letters. 2011;200(3):201–10. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexandra Alcántara Guardado BPO, Shuvo MAI, Lin Yirong, Hodges Deidra, Joddar Binata, editors. BMES. Tampa, Florida: 2015. Novel Graphene Oxide biocompatible coatings on 316L Stainless Steel meshes for vascular stent applications. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akhavan O, Ghaderi E. Differentiation of human neural stem cells into neural networks on graphene nanogrids. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2013;1(45):6291–301. doi: 10.1039/c3tb21085e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akyıldırım O, Kotan G, Yola ML, Eren T, Atar N. Fabrication of bimetallic Pt/Pd nanoparticles on 2-thiolbenzimidazole functionalized reduced graphene oxide for methanol oxidation. Ionics. 2016;22(4):593–600. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Depan D, Shah J, Misra R. Controlled release of drug from folate-decorated and graphene mediated drug delivery system: synthesis, loading efficiency, and drug release response. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2011;31(7):1305–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen J, Yao B, Li C, Shi G. An improved Hummers method for eco-friendly synthesis of graphene oxide. Carbon. 2013;64:225–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yola ML, Atar N, Eren T, Karimi-Maleh H, Wang S. Sensitive and selective determination of aqueous triclosan based on gold nanoparticles on polyoxometalate/reduced graphene oxide nanohybrid. RSC Adv. 2015;5(81):65953–62. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yokuş ÖA, Kardaş F, Akyıldırım O, Eren T, Atar N, Yola ML. Sensitive voltammetric sensor based on polyoxometalate/reduced graphene oxide nanomaterial: Application to the simultaneous determination of l-tyrosine and l-tryptophan. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 2016;233:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atar N, Eren T, Yola ML, Karimi-Maleh H, Demirdögen B. Magnetic iron oxide and iron oxide@ gold nanoparticle anchored nitrogen and sulfur-functionalized reduced graphene oxide electrocatalyst for methanol oxidation. RSC Advances. 2015;5(33):26402–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yola ML, Eren T, Atar N, Saral H, Ermiş İ. Direct-Methanol Fuel Cell Based on Functionalized Graphene Oxide with Mono-Metallic and Bi-Metallic Nanoparticles: Electrochemical Performances of Nanomaterials for Methanol Oxidation. Electroanalysis. 2015;28(3):10. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Elçin S, Yola ML, Eren T, Girgin B, Atar N. Highly Selective and Sensitive Voltammetric Sensor Based on Ruthenium Nanoparticle Anchored Calix [4] amidocrown-5 Functionalized Reduced Graphene Oxide: Simultaneous Determination of Quercetin, Morin and Rutin in Grape Wine. Electroanalysis. 2015;28(3):9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kotan G, Kardaş F, Yokuş ÖA, Akyıldırım O, Saral H, Eren T, et al. A novel determination of curcumin via Ru@ Au nanoparticle decorated nitrogen and sulfur-functionalized reduced graphene oxide nanomaterials. Analytical Methods. 2016;8(2):401–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akyıldırım O, Yüksek H, Saral H, Ermiş İ, Eren T, Yola ML. Platinum nanoparticles supported on nitrogen and sulfur-doped reduced graphene oxide nanomaterial as highly active electrocatalysts for methanol oxidation. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics. 27(8):8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Çolak AT, Eren T, Yola ML, Beşli E, Şahin O, Atar N. 3D Polyoxometalate-Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots with Mono-Metallic and Bi-Metallic Nanoparticles for Application in Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. Journal of The Electrochemical Society. 2016;163(10):F1237–F44. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Atar N, Yola ML, Eren T. Sensitive determination of citrinin based on molecular imprinted electrochemical sensor. Applied Surface Science. 2016;362:315–22. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Depan D, Pesacreta T, Misra R. The synergistic effect of a hybrid graphene oxide–chitosan system and biomimetic mineralization on osteoblast functions. Biomaterials Science. 2014;2(2):264–74. doi: 10.1039/c3bm60192g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crowder SW, Prasai D, Rath R, Balikov DA, Bae H, Bolotin KI, et al. Three-dimensional graphene foams promote osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Nanoscale. 2013;5(10):4171–6. doi: 10.1039/c3nr00803g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su Y, Kravets V, Wong S, Waters J, Geim A, Nair R. Impermeable barrier films and protective coatings based on reduced graphene oxide. Nature communications. 2014;5:4843. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh SK, Singh MK, Kulkarni PP, Sonkar VK, Grácio JJ, Dash D. Amine-modified graphene: thrombo-protective safer alternative to graphene oxide for biomedical applications. Acs Nano. 2012;6(3):2731–40. doi: 10.1021/nn300172t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cardenas L, MacLeod J, Lipton-Duffin J, Seifu D, Popescu F, Siaj M, et al. Reduced graphene oxide growth on 316L stainless steel for medical applications. Nanoscale. 2014;6(15):8664–70. doi: 10.1039/c4nr02512a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan M, Al-Marri AH, Khan M, Shaik MR, Mohri N, Adil SF, et al. Green approach for the effective reduction of graphene oxide using Salvadora persica L. root (miswak) extract. Nanoscale research letters. 2015;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s11671-015-0987-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moon IK, Kim JI, Lee H, Hur K, Kim WC, Lee H. 2D graphene oxide nanosheets as an adhesive over-coating layer for flexible transparent conductive electrodes. Scientific reports. 2013;3:1112. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pal R, Monroe TO, Palmieri M, Sardiello M, Rodney GG. Rotenone induces neurotoxicity through Rac1-dependent activation of NADPH oxidase in SHSY-5Y cells. FEBS letters. 2014;588(3):472–81. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li M, Liu Q, Jia Z, Xu X, Cheng Y, Zheng Y, et al. Graphene oxide/hydroxyapatite composite coatings fabricated by electrophoretic nanotechnology for biological applications. Carbon. 2014;67:185–97. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song J, Wang X, Chang C-T. Preparation and Characterization of Graphene Oxide. Journal of Nanomaterials. 2014;2014:6. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcano DC, Kosynkin DV, Berlin JM, Sinitskii A, Sun Z, Slesarev A, et al. Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS nano. 2010;4(8):4806–14. doi: 10.1021/nn1006368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lawrie G, Keen I, Drew B, Chandler-Temple A, Rintoul L, Fredericks P, et al. Interactions between alginate and chitosan biopolymers characterized using FTIR and XPS. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8(8):2533–41. doi: 10.1021/bm070014y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hermanson GT. Bioconjugate techniques. 3. Academic press; 2013. p. 1146. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beegan D, Chowdhury S, Laugier MT. Work of indentation methods for determining copper film hardness. Surface and Coatings Technology. 2005;192:57–63. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oliver WC, Pharr GM. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. Journal of Materials Research. 1992;7:1564–83. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oliver WC, Pharr GM. Measurment of hardness and elastic modulus by instrumented indentation: Advances in understanding and refinements to methodology. Journal of Materials Research. 2004;19:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee C, Wei X, Kysar JW, Hone J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science. 2008;321(5887):385–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1157996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Malzbender J, Den Toonder JMJ, Balkenende AR, De With G. Measuring mechanical properties of coatings: a methodology applied to nanoparticle-filled sol–gel coatings on glass. Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports. 2002;36(2):47–103. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kabiraj P, Marin JE, Varela-Ramirez A, Narayan M. An 11-mer Amyloid Beta Peptide Fragment Provokes Chemical Mutations and Parkinsonian Biomarker Aggregation in Dopaminergic Cells: A Novel Road Map for “Transfected” Parkinson’s. ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 2016;7(11):1519–30. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joddar B, Garcia E, Casas A, Stewart CM. Development of functionalized multi-walled carbon-nanotube-based alginate hydrogels for enabling biomimetic technologies. Scientific Reports. 2016;6:32456. doi: 10.1038/srep32456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ibrahim S, Joddar B, Craps M, Ramamurthi A. A surface-tethered model to assess size-specific effects of hyaluronan (HA) on endothelial cells. Biomaterials. 2007;28(5):825–35. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Joddar B, Firstenberg MS, Reen RK, Varadharaj S, Khan M, Childers RC, et al. Arterial Levels of Oxygen Stimulate Intimal Hyperplasia in Human Saphenous Veins via a ROS-Dependent Mechanism. PloS one. 2015;10(3):e0120301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Taha-Tijerina J, Venkataramani D, Aichele CP, Tiwary CS, Smay JE, Mathkar A, et al. Quantification of the Particle Size and Stability of Graphene Oxide in a Variety of Solvents. Particle & Particle Systems Characterization. 2015;32(3):334–9. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Finšgar M, Jackson J. Application of corrosion inhibitors for steels in acidic media for the oil and gas industry: a review. Corrosion Science. 2014;86:17–41. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Negm NA, Kandile NG, Badr EA, Mohammed MA. Gravimetric and electrochemical evaluation of environmentally friendly nonionic corrosion inhibitors for carbon steel in 1M HCl. Corrosion Science. 2012;65:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ebenso EE, Arslan T, Kandemirlı F, Love I, Öğretır Cl, Saracoğlu M, et al. Theoretical studies of some sulphonamides as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic medium. International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 2010;110(14):2614–36. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tang Y, Zhang F, Hu S, Cao Z, Wu Z, Jing W. Novel benzimidazole derivatives as corrosion inhibitors of mild steel in the acidic media. Part I: Gravimetric, electrochemical, SEM and XPS studies. Corrosion Science. 2013;74:271–82. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shuvo MAI, Khan MAR, Karim H, Morton P, Wilson T, Lin Y. Investigation of modified graphene for energy storage applications. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2013;5(16):7881–5. doi: 10.1021/am401978t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shuvo MAI, Rodriguez G, Islam MT, Karim H, Ramabadran N, Noveron JC, et al. Microwave Exfoliated Graphene Oxide/TiO2 Nanowire Hybrid for High Performance Lithium Ion Battery. Journal of Applied Physics. 2015;118(12):6. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lin Y, Ehlert GJ, Bukowsky C, Sodano HA. Superhydrophobic functionalized graphene aerogels. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2011;3(7):2200–3. doi: 10.1021/am200527j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meyers SR, Grinstaff MW. Biocompatible and bioactive surface modifications for prolonged in vivo efficacy. Chemical reviews. 2011;112(3):1615–32. doi: 10.1021/cr2000916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dey A, Mukhopadhyay AK, Gangadharan S, Sinha MK, Basu D, Bandyopadhyay NR. Nanoindentation study of microplasma sprayed hydroxyapatite coating. Ceramics International. 2009;35(6):2295–304. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Alok K, Krishanu B, Bikramjit B. Fretting wear behaviour of hydroxyapatite–titanium composites in simulated body fluid, supplemented with 5 g l–1 bovine serum albumin. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 2013;46(40):404004. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang Q-Y, Zhang Y-Y, Xie J, Li C-X, Chen W-Y, Liu B-L, et al. Stiff substrates enhance cultured neuronal network activity. Scientific reports. 2014;4:6215. doi: 10.1038/srep06215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.