Abstract

Polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA) has become a widely used technique for the rational design of diblock copolymer nano-objects in concentrated aqueous solution. Depending on the specific PISA formulation, reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) aqueous dispersion polymerization typically provides straightforward access to either spheres, worms, or vesicles. In contrast, RAFT aqueous emulsion polymerization formulations often lead to just kinetically-trapped spheres. This limitation is currently not understood, and only a few empirical exceptions have been reported in the literature. In the present work, the effect of monomer solubility on copolymer morphology is explored for an aqueous PISA formulation. Using 2-hydroxybutyl methacrylate (aqueous solubility = 20 g dm–3 at 70 °C) instead of benzyl methacrylate (0.40 g dm–3 at 70 °C) for the core-forming block allows access to an unusual “monkey nut” copolymer morphology over a relatively narrow range of target degrees of polymerization when using a poly(methacrylic acid) RAFT agent at pH 5. These new anisotropic nanoparticles have been characterized by transmission electron microscopy, dynamic light scattering, aqueous electrophoresis, shear-induced polarized light imaging (SIPLI), and small-angle X-ray scattering.

Introduction

In recent years, polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA) has become a widely recognized route for the synthesis of many types of diblock copolymer nano-objects.1−5 Compared to post-polymerization processing techniques (solvent exchange, film rehydration, or pH switch), PISA is much more efficient and can be performed at relatively high solids (10–50% w/w).3,6−8 This approach involves growth of an insoluble block from a soluble homopolymer in a suitable solvent to give well-defined sterically stabilized diblock copolymer nanoparticles. For example, reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) aqueous dispersion polymerization involves polymerization of a water-miscible monomer such as 2-hydroxypropyl methacrylate (HPMA) from a water-soluble stabilizer, e.g. poly(glycerol monomethacrylate).9,10 Such formulations enable the production of various copolymer morphologies such as spheres, worms or vesicles.11−19 RAFT aqueous emulsion polymerization has similarly received significant attention.2,6,7,20−24 In this case, a water-immiscible monomer is used to produce the hydrophobic core-forming block, but according to many literature reports only kinetically-trapped spheres can be obtained.6,7,24−31 Exceptionally, Charleux and co-workers reported the synthesis of diblock copolymer worms (described as “nanofibers”) and vesicles, as well as spheres.23,32−35 Recent empirical experiments have undoubtedly provided some useful insights,36 but the critical synthesis parameters that determine whether only kinetically-trapped spheres are obtained or the full range of morphologies are observed have not yet been established. In this context, Truong et al. recently synthesized novel “filomicelle nanomaterials” directly in water by employing RAFT aqueous emulsion polymerization followed by temperature-induced morphological transition. Morphological transitions from spherical micelles to filomicelles (worms) and/or vesicles were observed on cooling in the presence of additional monomer, which apparently acts as a plasticizer for the frustrated core-forming block.37 However, this approach does not seem to be particularly attractive from a commercial perspective, unless the additional monomer can be polymerized.

The present work explores the effect of monomer solubility on copolymer morphology. As noted above, water-miscible monomers such as HPMA (aqueous solubility ∼100 g dm–3 at 70 °C) are required for RAFT aqueous dispersion polymerization, whereas water-immiscible monomers such as benzyl methacrylate (BzMA; aqueous solubility ∼0.40 g dm–3 at 70 °C) are required for RAFT aqueous emulsion polymerization. Herein we utilize 2-hydroxybutyl methacrylate (HBMA) as a monomer of intermediate aqueous solubility (∼20 g dm–3 at 70 °C) that has been previously reported to undergo RAFT aqueous emulsion polymerization.38 The key question to be addressed is whether such formulations allow access to any copolymer morphologies other than kinetically-trapped spheres.

Experimental Section

Materials

Methacrylic acid (MAA), 2-hydroxybutyl methacrylate (HBMA; actually a 1:1 molar ratio of 2- and 4-isomers as judged by 1H NMR spectroscopy15), and 4,4′-azobis(4-cyanovaleric acid) (ACVA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich U.K. and used as received unless otherwise specified. Deionized water was used in all experiments. 4-cyano-4-(2-phenylethanesulfanylthiocarbonyl)sulfanylpentanoic acid (PETTC) was prepared as described previously.39 The trimethylsilyldiazomethane solution (2.0 M in diethyl ether), THF (HPLC, ≥99.9%), and glacial acetic acid (≥99.85%) used for the preparation and analysis of the methylated diblock copolymers were also purchased from Sigma-Aldrich U.K. Methanol-d4, dimethyl sulfoxide-d6, and dimethylformamide-d7 used for 1H NMR spectroscopy were purchased from Goss Scientific Instruments Ltd. (Cheshire, U.K.). All other solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich U.K. or VWR Chemicals.

Preparation of Poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA) Macro-CTA Agent

PETTC RAFT agent (3.169 g, 0.0093 mol), MAA (45.00 g, 0.5227 mol), ACVA (0.523 g, 0.001 mol; CTA/initiator molar ratio = 5.0), and ethanol (73.04 g, 40% w/w) were weighed into a 500 mL round-bottom flask and degassed with nitrogen for 30 min in an ice bath. The reaction solution was then heated for 3 h at 70 °C in a preheated oil bath. The resulting macro-CTA was then purified by precipitation into diethyl ether (1.5 L). The polymer was collected by filtration and redissolved in the minimum amount of ethanol, before a second precipitation step. The polymer was then collected and redissolved in the minimum amount of water for isolation by lyophilization. The mean degree of polymerization was calculated to be 56 for this macro-CTA by 1H NMR. This synthesis was also performed using (4-cyano-4-(phenylcarbonothioylthio)pentanoic acid) (CPCP) as the RAFT agent.

RAFT Polymerization of HBMA in Water

A typical protocol for the synthesis of PMAA56–PHBMA500 was as follows: PMAA56 macro-CTA (0.0489 g, 0.0094 mmol), ACVA (0.6 mg, 0.0019 mmol, macro-CTA/initiator molar ratio = 5.0), and water (3.20 g, 20% w/w) were weighed into a 14 mL vial. The pH was adjusted to pH 5 using 1 M NaOH. HBMA monomer (0.7500 g, 4.70 mmol) was then added, and the reaction vial was sealed and purged for 30 min before being placed in a preheated oil bath at 70 °C for 18 h.

Purification of HBMA Monomer

As-received HBMA (3.0 g) was dissolved in water (300 g). This aqueous monomer solution was extracted using n-hexane to remove the dimethacrylate impurity. The aqueous monomer solution was then salted with NaCl (250 g/L), and HBMA was removed from the aqueous phase by extraction with diethyl ether. MgSO4 was added to remove traces of water from the ether layer. Hydroquinone (0.1%) was added to prevent thermal polymerization prior to removal of the solvent by distillation under reduced pressure to afford purified HBMA monomer.

Copolymer Characterization

1H NMR Spectroscopy

All 1H NMR spectra were recorded using a 400 MHz Bruker Advance-400 spectrometer using either methanol-d4, dimethyl sulfoxide-d6, or dimethylformamide-d7.

Exhaustive Methylation of Copolymers for GPC Analysis

Prior to gel permeation chromatography analysis, all copolymers were modified by exhaustive methylation of the carboxylic acid groups in the PMAA block. Excess trimethylsilyldiazomethane was added dropwise to a solution of copolymer (20 mg) in THF (2.0 mL), until the yellow color persisted. This reaction solution was then stirred overnight until all THF had evaporated. Degrees of methylation of the PMAA block were determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

THF GPC at 60 °C was used to determine the molecular weights and dispersities of the modified copolymers. The GPC setup consisted of two 5 μM Mixed C columns connected to a WellChrom K-2301 refractive index detector. The mobile phase was HPLC-grade THF containing 1.0% glacial acetic acid and 0.05% w/v butylhydroxytoluene (BHT) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min–1. Molecular weights were calculated with respect to a series of near-monodisperse poly(methyl methacrylate) standards.

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS)

Aqueous copolymer dispersions (0.20% w/w) in disposable plastic cuvettes were analyzed using a Malvern Zetasizer NanoZS instrument. The mean hydrodynamic particle diameter was averaged over three consecutive runs.

Aqueous Electrophoresis

Measurements were performed using a Malvern Zetasizer instrument on dilute (0.20% w/w) copolymer dispersions containing background KCl (1 mM). The solution pH was adjusted by addition of either NaOH or HCl.

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

One droplet (10 μL) of a dilute copolymer dispersion (0.20% w/w) was deposited onto a carbon-coated copper grid. The grid was then stained with 10 μL uranyl formate for 10 s and dried using a vacuum hose. TEM images were then obtained using a Philips CM100 instrument operating at 100 kV and equipped with a Gatan 1 k CCD camera.

Reverse-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

The level of dimethacrylate impurity in the HBMA monomer was quantified by HPLC. The experimental setup consisted of an autosampler (Varian model 410), a solvent delivery module (Varian Module 230), a UV detector (Varian model 310), and an Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18, 3.5 μm, 4.6 × 100 mm HPLC column. HBMA (5.0 mg) was weighed into an autosampler vial and dissolved in acetonitrile (1.0 mL). The eluent was gradually varied from an initial composition of 5% acetonitrile in water to 95% acetonitrile in water after 15–20 min. The UV detector was set to a wavelength of 210 nm.

Shear-Induced Polarized Light Imaging (SIPLI)

Shear alignment experiments were conducted using a mechano-optical rheometer (Anton Paar Physica MCR301 with SIPLI attachment). Measurements were performed using a plate–plate geometry composed of a 25 mm polished steel plate and a fused quartz plate connected to a variable temperature Peltier system. The gap between plates was set at 0.50 mm for all experiments. An additional Peltier hood was used to ensure good control of the sample temperature. Sample illumination was achieved using an Edmund Optics 150 W MI-150 high-intensity fiber-optic white light source. The polarizer and analyzer axes were crossed at 90° in order to obtain polarized light images (PLIs), which were recorded using a color CCD camera (Lumenera Lu165c).

Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS)

SAXS patterns for PMAA56–PHBMAy (y = 150, 300, and 1000) were recorded at a synchrotron source (ESRF, station ID02, Grenoble, France) using monochromatic X-ray radiation (wavelength λ = 0.0995 nm, with q ranging from 0.004 to 2.5 nm–1, where q = 4π sin θ/λ is the length of the scattering vector and θ is one-half of the scattering angle) and a Rayonix MX-170HS Kodak CCD detector. Measurements were conducted on 1.0% w/w aqueous dispersions at pH 5 using glass capillaries of 2.0 mm diameter. X-ray scattering data were reduced using standard routines from the beamline and were further analyzed using Irena SAS macros for Igor Pro.40 The SAXS pattern for PMAA56–PHBMA50 was obtained using a Bruker AXS Nanostar laboratory instrument modified with a microfocus X-ray tube (GeniX3D, Xenocs) and motorized scatterless slits for the beam collimation (camera length = 1.46 m, Cu Kα radiation, and HiSTAR multiwire gas detector). In this case the SAXS pattern was recorded for a 1.0 % w/w aqueous dispersion at pH 5 over a q range of 0.08 nm–1 < q > 1.6 nm –1 using a glass capillary of 2.0 mm diameter and an exposure time of 1.0 h. Raw SAXS data were reduced using Nika macros for Igor Pro written by J. Ilavsky. All SAXS patterns were analyzed (background subtraction, data modeling and fitting) using Irena SAS macros for Igor Pro.40

Results and Discussion

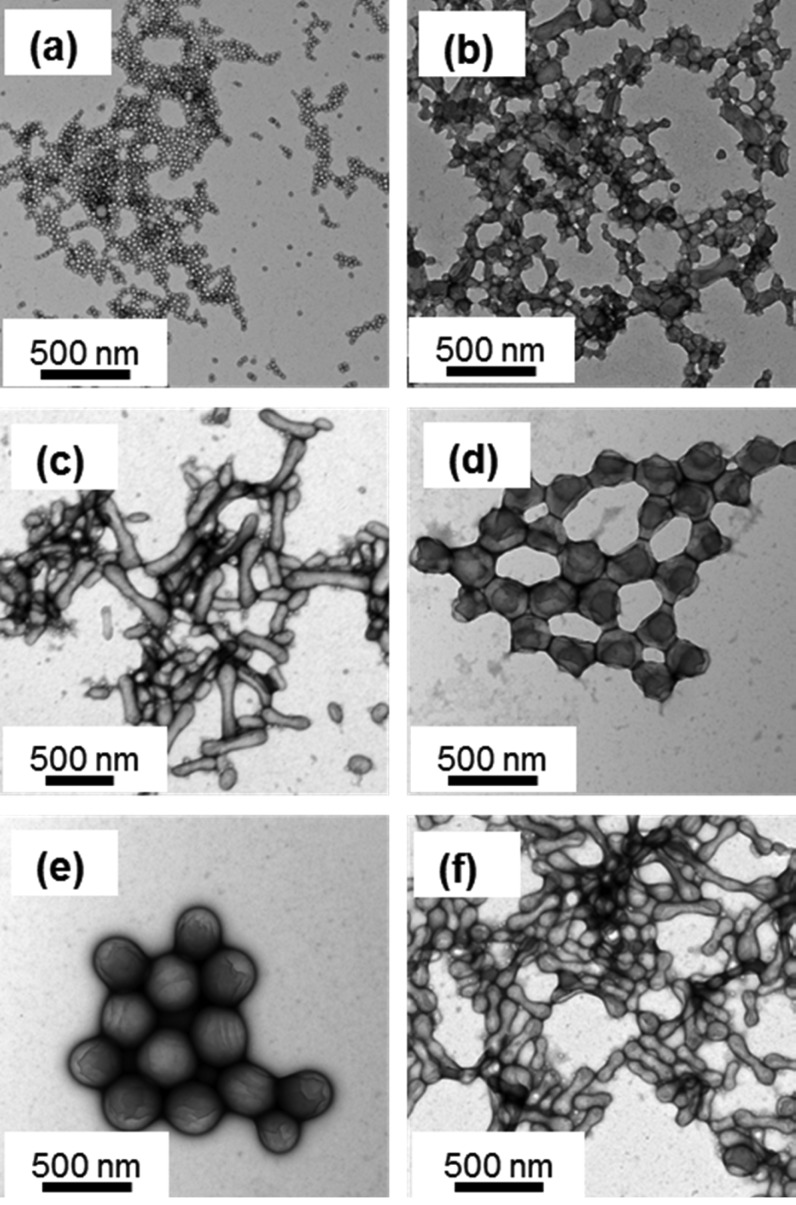

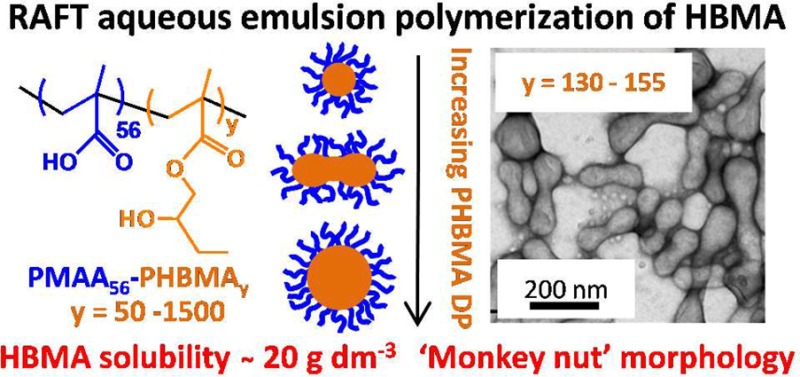

A PMAA56 macromolecular chain transfer agent (macro-CTA) was chain-extended with HBMA via RAFT polymerization at 70 °C conducted in aqueous solution at pH 5 (see Scheme 1). The target degree of polymerization (DP) for the structure-directing PHBMA block was varied between 50 and 1500. All polymerizations proceeded to high conversion (>96%) as judged by 1H NMR spectroscopy studies in DMF-d7. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) studies were conducted to determine the copolymer morphology (Figure 1). For target PHBMA DPs of 50–145, the PMAA56–PHBMAy diblock copolymer chains self-assembled to form well-defined spheres of 80–175 nm diameter. However, TEM studies indicated that a new “monkey nut” morphology could be obtained over a rather narrow range of y values (y = 150 or 155). These “monkey nuts” are approximately 100–800 nm in length, with widths varying from 25 to 125 nm; thus, the mean length/width ratio (or particle anisotropy) is approximately four. This unusual non-spherical morphology clearly demonstrates that using a monomer of intermediate aqueous solubility such as HBMA allows access to morphologies other than kinetically-trapped spheres. However, only relatively large spherical particles of 200–400 nm diameter were formed when targeting higher PHBMA DPs (up to y = 1500).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Poly(methacrylic acid)–Poly(2-hydroxybutyl methacrylate) (PMAA–PHBMA) Diblock Copolymer Nanoparticles via RAFT Polymerization in Aqueous Solution.

Increasing the target degree of polymerization of the PHBMA core-forming block alters both the particle diameter and particle morphology.

Figure 1.

TEM images obtained for PMAA56–PHBMAy diblock copolymer nanoparticles prepared at 20% w/w solids via RAFT aqueous emulsion polymerization at 70 °C. Polymerization-induced self-assembly (PISA) leads to the formation of small spherical nanoparticles for (a) PMAA56–PHBMA50 and (b) PMAA56–PHBMA130. Synthesis of (c) PMAA56–PHBMA150 produces a distinctive “monkey nut” morphology. However, targeting a mean degree of polymerization for the PHBMA block of either (d) 300 or (e) 1000 only leads to the formation of relatively large spheres. (f) PISA syntheses conducted using a purified batch of HBMA monomer also produce a “monkey nut” morphology when targeting PMAA56–PHBMA150, clearly indicating that this unusual morphology is not simply the result of in situ cross-linking as a result of the dimethacrylate impurity in the HBMA monomer.

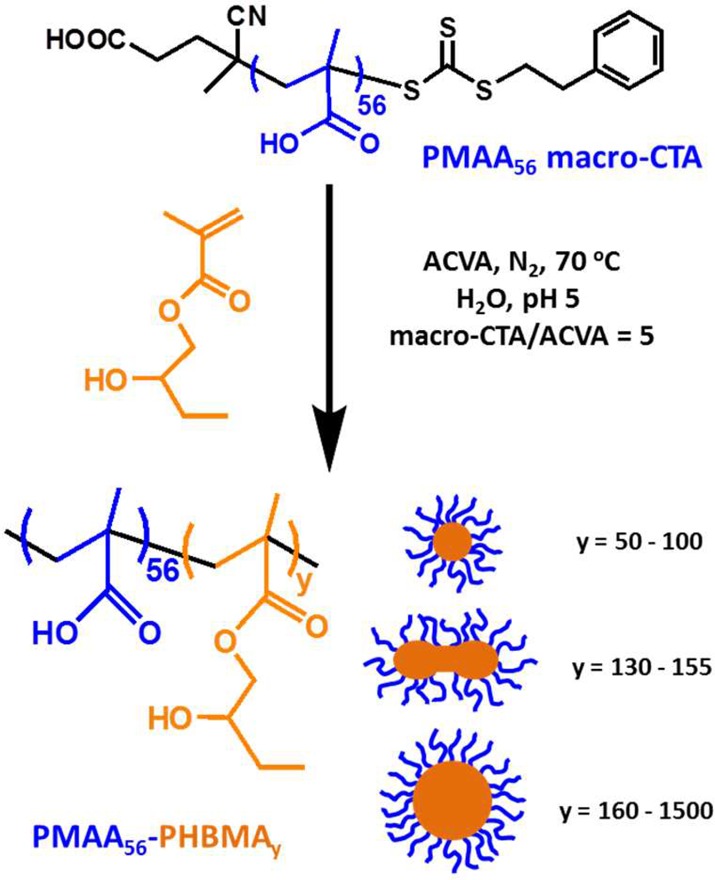

Aqueous electrophoresis was used to assess the mobility and zeta potential of these diblock copolymer nano-objects. The effect of varying pH on the apparent sphere-equivalent particle diameter and zeta potential of the PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nut” nanoparticles was evaluated by DLS and aqueous electrophoresis, respectively (see Figure 2). Between pH 10 and pH 5.5, the PMAA stabilizer chains were highly ionized, leading to negative zeta potentials ranging from −50 to −45 mV. The PMAA stabilizer chains remained highly anionic over this pH range, with only a modest reduction in particle diameter from 200 to 165 nm being observed (DLS polydispersities ranged from 0.03 to 0.09). This is consistent with ionized PMAA chains acting as a polyelectrolytic stabilizer block, conferring electrosteric stabilization during the PISA synthesis. Between pH 5.5 and pH 3.5, the zeta potential is gradually lowered to −20 mV as the PMAA chains become progressively more protonated. A concomitant reduction in apparent hydrodynamic particle diameter to 150 nm occurs as the PMAA chains start to collapse. However, an apparent particle diameter of 5 μm is observed by DLS at approximately pH 2.5. This is the result of flocculation of the PMAA56–PHBMA150 nanoparticles because the near-neutral PMAA stabilizer chains no longer confer effective electrosteric stabilization at this pH. Such aggregation proved to be reversible: on raising the solution pH from pH 3.5 to pH 10. The PMAA chains become ionized again, and approximately the original sphere-equivalent nanoparticle diameter was obtained, with a corresponding zeta potential of around −40 mV.

Figure 2.

Variation in apparent sphere-equivalent particle diameter (as judged by DLS) and zeta potential with pH curves for PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nut” nanoparticles prepared using purified HBMA monomer. Filled spheres (●) indicate titration from pH 10 to pH 2. Open spheres (○) indicate titration from pH 2 to pH 10. Particle flocculation is observed below pH 3.5 due to the loss of electrosteric stabilization as the PMAA chains become less anionic. This flocculation is reversible on addition of NaOH.

In principle, the molecular weight distributions of such PMAA56–PHBMAy diblock copolymers can be assessed by gel permeation chromatography (GPC). However, in practice the MAA residues require exhaustive methylation to prevent adsorption onto the GPC column. Unfortunately, the original methylated PMAA56–PHBMAy diblock copolymers proved to be insoluble in both THF and DMF, making GPC analysis impossible. This is believed to be the result of extensive cross-linking caused by the ∼4.4 mol % dimethacrylate impurity in the HBMA monomer. Similar problems have been reported for PISA syntheses involving HPMA.10,13 In order to address this technical problem, the HBMA monomer was purified prior to the preparation of a second series of PMAA56–PHBMAy diblock copolymers. Moreover, analysis of such diblock copolymer nano-objects should establish whether the unusual “monkey nut” morphology is merely an artifact caused by in situ cross-linking. In this context, it is worth noting that Sugihara and co-workers reported a “lumpy rod” morphology for the synthesis of cross-linked nanoparticles prepared via RAFT aqueous dispersion copolymerization of HPMA with EGDMA when targeting more than six EGDMA units per copolymer chain.41 Thus an aqueous solution of the as-supplied HBMA monomer was extracted using n-hexane to remove the dimethacrylate impurity.42 The purified HBMA monomer was analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC, which indicated approximately 87% removal of the original dimethacrylate impurity, leaving around 0.57 mol % dimethacrylate still present. A series of PMAA56–PHBMAy diblock copolymers (targeting y = 130–300) were then prepared using this purified HBMA monomer. The MAA residues of the diblock copolymer chains were exhaustively methylated using excess trimethylsilyldiazomethane and proved to be fully soluble in a THF eluent containing 1.0% glacial acetic acid,43 which indicates a substantial reduction in the degree of cross-linking. The molecular weight of the diblock copolymer chains increased as the target PHBMA DP was varied from 130 to 300, but dispersities ranged from 1.18 to 6.13, which suggests substantial branching (see Figure S1, Supporting Information).44,45 TEM analysis of this second series of PMAA56–PHBMAy nano-objects prepared using purified HBMA monomer confirmed that a “monkey nut” copolymer morphology could still be obtained. Thus, such nano-objects do not appear to be an artifact caused by cross-linking. Moreover, the “monkey nut” morphology is observed for PHBMA DPs of 130–155, which is somewhat a somewhat broader range than that obtained when using the as-received HBMA monomer.

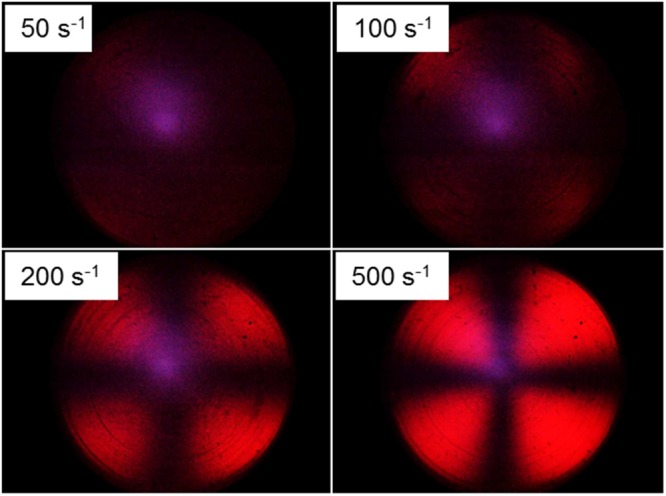

PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nut” nanoparticles prepared using purified HBMA monomer were analyzed using the shear-induced polarized light imaging (SIPLI) technique.46−49 It is well-known that anisotropic nanoparticles can be aligned when subjected to an applied shear.50,51 Above a certain critical shear rate, alignment in the direction of flow leads to shear-thinning behavior and the observation of birefringence. In a SIPLI experiment, linearly polarized white light is directed through a transparent quartz plate on which an aqueous dispersion of PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nuts” at 20% w/w solids is placed. After transmission through the dispersion, the light is reflected by a polished steel plate and then analyzed at 90° to the plane of polarization using a CCD camera. Because the reflected light is analyzed at 90° to the incident light, only rotated light is detected. Particle alignment leads to the observation of a characteristic Maltese cross pattern. The PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nut” nanoparticles were subjected to maximum shear rates ranging from 50 to 500 s–1 (Figure 3). There is a shear rate gradient across the polished steel plate from its center to the periphery, with the maximum shear rate being obtained at the plate edge. A characteristic Maltese cross pattern was observed at maximum shear rates of either 200 or 500 s–1, indicating alignment of anisotropic nanoparticles. The critical shear rate for nanoparticle alignment can be calculated from the image at a maximum shear rate of 100 s–1, where a partial Maltese cross pattern is obtained with a dark circle in the center. The critical shear rate under these conditions is 40 s–1, which corresponds to a mean relaxation time of approximately 25 ms. This represents the time scale required to produce an isotropic dispersion after cessation of the applied shear.

Figure 3.

Shear-Induced Polarized Light Images (SIPLIs) obtained for a 20% w/w aqueous dispersion of PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nut” nanoparticles at maximum shear rates of 50, 100, 200, and 500 s–1. A Maltese cross is observed above a critical shear rate of 40 s–1, indicating shear-induced alignment. Thus the mean relaxation time of the “monkey nut” nanoparticles corresponds to approximately 25 ms.

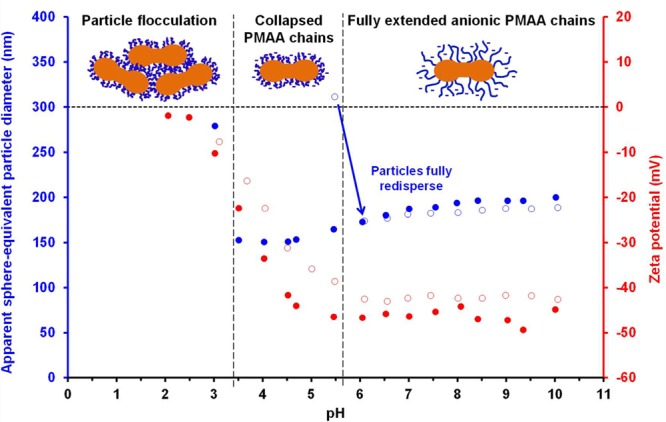

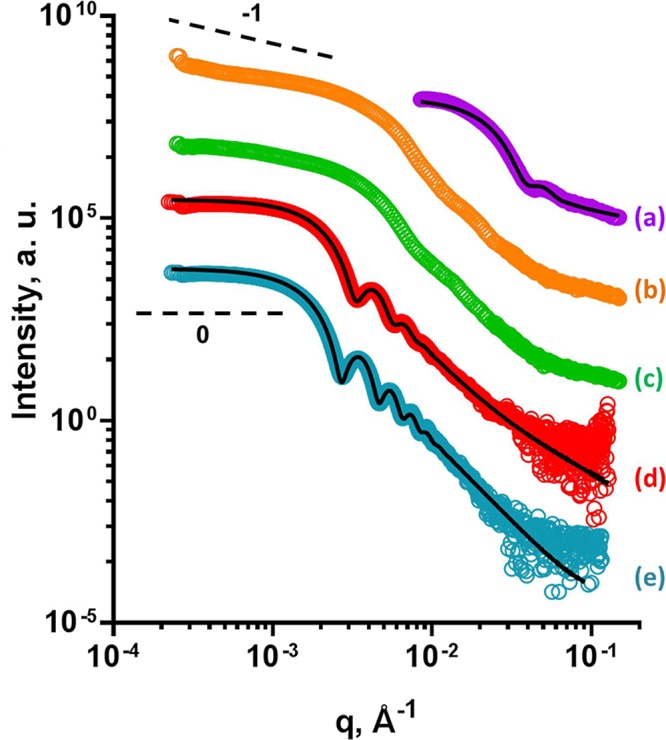

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS; see Figure 4) was used to confirm the copolymer morphologies indicated by TEM studies. To a good first approximation, the copolymer morphology is indicated by the gradient in the low q regime. Spherical micelles are characterized by a gradient of zero and rigid rods possess a gradient of negative unity.52 Although they exhibit considerable flexibility, highly anisotropic diblock copolymer worms prepared via PISA behave more or less like rigid rods in terms of their SAXS patterns.53,54 Inspecting Figure 4, the I(q) vs q scattering pattern recorded for a 1.0% w/w dispersion of PMAA56–PHBMA50 diblock copolymer nanoparticles can be satisfactorily fitted to a previously reported spherical micelle model, with a volume-average core diameter of 19 ± 3 nm.55 The same spherical micelle model also provided good fits to the scattering patterns obtained for the PMAA56–PHBMA300 and PMAA56–PHBMA1000 nanoparticles. In each case, the gradient at low q of approximately zero confirms the spherical morphology indicated by TEM studies, with SAXS volume-average diameters estimated to be 262 ± 26 and 330 ± 22 nm, respectively. These analyses enable us to reject our initial hypothesis that the latter nano-objects might be thick-walled vesicles, not least because there is no evidence for any membrane structure. Moreover, the presence of multiple fringes in these latter two scattering patterns suggests relatively narrow size distributions in each case. In contrast, the scattering patterns recorded for the PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nut” nanoparticles (synthesized with either the as-received or the purified HBMA monomer) cannot be fitted using the spherical model. These patterns have low q gradients of −0.82 and −0.71, respectively, confirming that these nanoparticles possess significant anisotropic character (as suggested by TEM analysis). In addition, the lack of a well-defined local minimum at high q suggests that these “monkey nut” nanoparticles are relatively polydisperse in terms of their mean widths. Although not yet fully analyzed, these preliminary SAXS data are important because they are much more statistically robust than TEM analyses. They confirm a unique evolution in copolymer morphology for this PMAA56–PHBMAy RAFT aqueous emulsion formulation, from small spheres to “monkey nuts” to large spheres with increasing y values. We hypothesize that a higher aqueous monomer solubility facilitates more effective plasticization of the core-forming block on the time scale of the polymerization, which in turn facilitates the stochastic 1D fusion of the growing monomer-swollen spheres to form the “monkey nut” copolymer morphology, rather than kinetically-trapped spheres. However, a detailed mechanistic explanation for these morphological observations will clearly require further studies that are beyond the scope of the present work.

Figure 4.

SAXS patterns obtained from 1.0% w/w aqueous dispersions of PMAA56–PHBMAy diblock copolymer nano-objects at pH 5: (a) PMAA56–PHBMA50 spheres, (b) PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nut” nanoparticles (prepared using purified HBMA monomer), (c) PMAA56–PHBMA150 “monkey nut” nanoparticles (prepared using as-received HBMA monomer), (d) PMAA56–PHBMA300 spheres, and (e) PMAA56–PHBMA1000 spheres.

In summary, the RAFT aqueous emulsion polymerization of HBMA at pH 5 using a PMAA56 macro-CTA leads to the formation of elongated nanoparticles with a highly unusual “monkey nut” morphology over a relatively narrow range of core-forming block DPs. This nanoparticle anisotropy is confirmed by SAXS analysis and is sufficient to enable alignment under shear, as indicated by shear-induced polarized light imaging studies. This suggests that the aqueous solubility of the monomer can play an important role in determining the copolymer morphology obtained during aqueous PISA syntheses. In future work, we plan to fit the SAXS scattering patterns obtained for these “monkey nut” nanoparticles using an appropriate new analytical model.

Acknowledgments

EPSRC and AkzoNobel (Slough, UK) are thanked for funding a CDT PhD CASE studentship for A.A.C. S.P.A. also acknowledges an ERC Advanced Investigator grant (PISA 320372). Dr. C. Gonzato is thanked for preparing the PMAA56 macro-CTA. Dr. J. Madsen is thanked for his help with the HPLC analysis of the HBMA monomer. The authors are grateful to ESRF for providing SAXS beam-time and the personnel of the ID02 station are thanked for their technical assistance with the synchrotron experiments reported in this paper.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.macromol.6b02309.

THF GPC curves obtained when using the purified HBMA monomer, summary table for SAXS structural parameters, additional polymerization kinetics data, and TEM images of diblock copolymers made using a shorter PMAA29 macro-CTA (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Charleux B.; Delaittre G.; Rieger J.; D’Agosto F. Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly: From Soluble Macromolecules to Block Copolymer Nano-Objects in One Step. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 6753–6765. 10.1021/ma300713f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canning S. L.; Smith G. N.; Armes S. P. A Critical Appraisal of RAFT-Mediated Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 1985–2001. 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b02602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry M. J.; Fielding L. A.; Armes S. P. Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly of Block Copolymer Nanoparticles via RAFT Non-Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 52, 1–18. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.10.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai W.; Wan W.; Hong C.; Huang C.; Pan C. Morphology Transitions in RAFT Polymerization. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 5554–5561. 10.1039/c0sm00284d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warren N. J.; Armes S. P. Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly of Block Copolymer Nano-objects via RAFT Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 10174–10185. 10.1021/ja502843f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham V. J.; Alswieleh A. M.; Thompson K. L.; Williams M.; Leggett G. J.; Armes S. P.; Musa O. M. Poly(glycerol monomethacrylate)–Poly(benzyl methacrylate) Diblock Copolymer Nanoparticles via RAFT Emulsion Polymerization: Synthesis, Characterization, and Interfacial Activity. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 5613–5623. 10.1021/ma501140h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger J.; Zhang W.; Stoffelbach F.; Charleux B. Surfactant-Free RAFT Emulsion Polymerization Using Poly(N,N-dimethylacrylamide) Trithiocarbonate Macromolecular Chain Transfer Agents. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 6302–6310. 10.1021/ma1009269. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binauld S.; Delafresnaye L.; Charleux B.; D’Agosto F.; Lansalot M. Emulsion Polymerization of Vinyl Acetate in the Presence of Different Hydrophilic Polymers Obtained by RAFT/MADIX. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 3461–3472. 10.1021/ma402549x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanazs A.; Armes S. P.; Ryan A. J. Self-Assembled Block Copolymer Aggregates: From Micelles to Vesicles and their Biological Applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2009, 30, 267–277. 10.1002/marc.200800713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanazs A.; Madsen J.; Battaglia G.; Ryan A. J.; Armes S. P. Mechanistic Insights for Block Copolymer Morphologies: How Do Worms Form Vesicles?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 16581–16587. 10.1021/ja206301a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Qiu Q.; An Z. Development of Thermosensitive Copolymers of poly(2-methoxyethyl acrylate-co-poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether acrylate) and their Nanogels Synthesized by RAFT Dispersion Polymerization in Water. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 504–513. 10.1039/C2PY00533F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G.; Qiu Q.; Shen W.; An Z. Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization of 2-Methoxyethyl Acrylate for the Synthesis of Biocompatible Nanoparticles Using a Hydrophilic RAFT Polymer and a Redox Initiator. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 5237–5245. 10.1021/ma200984h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Armes S. P. RAFT Synthesis of Sterically Stabilized Methacrylic Nanolatexes and Vesicles by Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4042–4046. 10.1002/anie.201001461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanazs A.; Ryan A. J.; Armes S. P. Predictive Phase Diagrams for RAFT Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization: Effect of Block Copolymer Composition, Molecular Weight, and Copolymer Concentration. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 5099–5107. 10.1021/ma301059r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe L. P. D.; Ryan A. J.; Armes S. P. From a Water-Immiscible Monomer to Block Copolymer Nano-Objects via a One-Pot RAFT Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization Formulation. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 769–777. 10.1021/ma301909w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W.; Chang Y.; Liu G.; Wang H.; Cao A.; An Z. Biocompatible, Antifouling, and Thermosensitive Core–Shell Nanogels Synthesized by RAFT Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 2524–2530. 10.1021/ma200074n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W.; Qu Q.; Xu Y.; An Z. Aqueous Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly for the Synthesis of Ketone-Functionalized Nano-Objects with Low Polydispersity. ACS Macro Lett. 2015, 4, 495–499. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.5b00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara S.; Ma’Radzi A. H.; Ida S.; Irie S.; Kikukawa T.; Maeda Y. In situ nano-objects via RAFT Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization of 2-methoxyethyl acrylate using poly(ethylene oxide) Macromolecular Chain Transfer Agent as Steric Stabilizer. Polymer 2015, 76, 17–24. 10.1016/j.polymer.2015.08.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara S.; Blanazs A.; Armes S. P.; Ryan A. J.; Lewis A. L. Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization: A New Paradigm for in Situ Block Copolymer Self-Assembly in Concentrated Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (39), 15707. 10.1021/ja205887v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham M. F. Controlled/living Radical Polymerization in Aqueous Dispersed Systems. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2008, 33, 365–398. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2007.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson C. J.; Hughes R. J.; Pham B. T. T.; Hawkett B. S.; Gilbert R. G.; Serelis A. K.; Such C. H. Effective ab Initio Emulsion Polymerization under RAFT Control. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 9243–9245. 10.1021/ma025626j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson C. J.; Hughes R. J.; Nguyen D.; Pham B. T. T.; Gilbert R. G.; Serelis A. K.; Such C. H.; Hawkett B. S. Ab Initio Emulsion Polymerization by RAFT-Controlled Self-Assembly. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 2191–2204. 10.1021/ma048787r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Boissé S.; Zhang W.; Beaunier P.; D’Agosto F.; Rieger J.; Charleux B. Well-Defined Amphiphilic Block Copolymers and Nano-objects Formed in Situ via RAFT-Mediated Aqueous Emulsion Polymerization. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 4149–4158. 10.1021/ma2005926. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truong N. P.; Dussert M. V.; Whittaker M. R.; Quinn J. F.; Davis T. P. Rapid Synthesis of Ultrahigh Molecular Weight and Low Polydispersity Polystyrene Diblock Copolymers by RAFT-mediated Emulsion Polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 3865–3874. 10.1039/C5PY00166H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger J.; Stoffelbach F.; Bui C.; Alaimo D.; Jérôme C.; Charleux B. Amphiphilic Poly(ethylene oxide) Macromolecular RAFT Agent as a Stabilizer and Control Agent in ab Initio Batch Emulsion Polymerization. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 4065–4068. 10.1021/ma800544v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; D’Agosto F.; Boyron O.; Rieger J.; Charleux B. One-Pot Synthesis of Poly(methacrylic acid-co-poly(ethylene oxide) methyl ether methacrylate)-b-polystyrene Amphiphilic Block Copolymers and Their Self-Assemblies in Water via RAFT-Mediated Radical Emulsion Polymerization. A Kinetic Study. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 7584–7593. 10.1021/ma201515n. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaduc I.; Zhang W.; Rieger J.; Lansalot M.; D’Agosto F.; Charleux B. Amphiphilic Block Copolymers from a Direct and One-pot RAFT Synthesis in Water. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2011, 32, 1270–1276. 10.1002/marc.201100240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaduc I.; Girod M.; Antoine R.; Charleux B.; D’Agosto F.; Lansalot M. Batch Emulsion Polymerization Mediated by Poly(methacrylic acid) MacroRAFT Agents: One-Pot Synthesis of Self-Stabilized Particles. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 5881–5893. 10.1021/ma300875y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaduc I.; Crepet A.; Boyron O.; Charleux B.; D’Agosto F.; Lansalot M. Effect of the pH on the RAFT Polymerization of Acrylic Acid in Water. Application to the Synthesis of Poly(acrylic acid)-Stabilized Polystyrene Particles by RAFT Emulsion Polymerization. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 6013–6023. 10.1021/ma401070k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fréal-Saison S.; Save M.; Bui C.; Charleux B.; Magnet S. Emulsifier-Free Controlled Free-Radical Emulsion Polymerization of Styrene via RAFT Using Dibenzyltrithiocarbonate as a Chain Transfer Agent and Acrylic Acid as an Ionogenic Comonomer: Batch and Spontaneous Phase Inversion Processes. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 8632–8638. 10.1021/ma061572s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manguian M.; Save M.; Charleux B. Batch Emulsion Polymerization of Styrene Stabilized by a Hydrophilic Macro-RAFT Agent. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2006, 27, 399–404. 10.1002/marc.200500807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boissé S.; Rieger J.; Belal K.; Di-Cicco A.; Beaunier P.; Li M.-H.; Charleux B. Amphiphilic Block Copolymer Nano-fibers via RAFT-mediated Polymerization in Aqueous Dispersed System. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 1950–1952. 10.1039/b923667h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissé S.; Rieger J.; Pembouong G.; Beaunier P.; Charleux B. Influence of the Stirring Speed and CaCl2 Concentration on the Nano-object Morphologies Obtained via RAFT-mediated Aqueous Emulsion Polymerization in the Presence of a Water-soluble macroRAFT Agent. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 3346–3354. 10.1002/pola.24771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; D’Agosto F.; Boyron O.; Rieger J.; Charleux B. Toward a Better Understanding of the Parameters that Lead to the Formation of Nonspherical Polystyrene Particles via RAFT-Mediated One-Pot Aqueous Emulsion Polymerization. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 4075–4084. 10.1021/ma300596f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; D’Agosto F.; Dugas P.-Y.; Rieger J.; Charleux B. RAFT-mediated One-pot Aqueous Emulsion Polymerization of Methyl methacrylate in the presence ofPoly(methacrylic acid-co-poly(ethylene oxide) methacrylate) trithiocarbonate Macromolecular Chain Transfer Agent. Polymer 2013, 54, 2011–2019. 10.1016/j.polymer.2012.12.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage de la Haye J.; Zhang X.; Chaduc I.; Brunel F.; Lansalot M.; D’Agosto F. The Effect of Hydrophile Topology in RAFT-Mediated Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3739–3743. 10.1002/anie.201511159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong N. P.; Quinn J. F.; Anastasaki A.; Haddleton D. M.; Whittaker M. R.; Davis T. P. Facile Access to Thermoresponsive Filomicelles with Tuneable Cores. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4497–4500. 10.1039/C6CC00900J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe L. P. D.; Blanazs A.; Williams C. N.; Brown S. L.; Armes S. P. RAFT Polymerization of Hydroxy-functional Methacrylic Monomers under Heterogeneous Conditions: Effect of Varying the Core-Forming Block. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 3643–3655. 10.1039/c4py00203b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Semsarilar M.; Ladmiral V.; Blanazs A.; Armes S. P. Poly(methacrylic acid)-based AB and ABC Block Copolymer Nano-objects Prepared via RAFT Alcoholic Dispersion Polymerization. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 3466–3475. 10.1039/c4py00201f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilavsky J.; Jemian P. R. Irena: Tool Suite for Modeling and Analysis of Small-Angle Scattering. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2009, 42, 347–353. 10.1107/S0021889809002222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara S.; Armes S. P.; Blanazs A.; Lewis A. L. Non-Spherical Morphologies from Cross-linked Biomimetic Diblock Copolymers using RAFT Aqueous Dispersion Polymerization. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 10787–10793. 10.1039/c1sm06593a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coca S.; Jasieczek C. B.; Beers K. L.; Matyjaszewski K. Polymerization of Acrylates by Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization. Homopolymerization of 2-Hydroxyethyl Acrylate. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 1998, 36, 1417–1424. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Couvreur L.; Lefay C.; Belleney J.; Charleux B.; Guerret O.; Magnet S. First Nitroxide-Mediated Controlled Free-Radical Polymerization of Acrylic Acid. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 8260–8267. 10.1021/ma035043p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister I.; Billingham N. C.; Armes S. P.; Rannard S. P.; Findlay P. Development of Branching in Living Radical Copolymerization of Vinyl and Divinyl Monomers. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 7483–7492. 10.1021/ma061811b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselgong J.; Armes S. P.; Barton W. R. S.; Price D. Synthesis of Branched Methacrylic Copolymers: Comparison between RAFT and ATRP and Effect of Varying the Monomer Concentration. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 2145–2156. 10.1021/ma902757z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mykhaylyk O. O. Time-Resolved Polarized Light Imaging of Sheared Materials: Application to Polymer Crystallization. Soft Matter 2010, 6, 4430–4440. 10.1039/c0sm00332h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mykhaylyk O. O.; Chambon P.; Impradice C.; Fairclough J. P. A.; Terrill N. J.; Ryan A. J. Control of Structural Morphology in Shear-Induced Crystallization of Polymers. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 2389–2405. 10.1021/ma902495z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mykhaylyk O. O.; Parnell A. J.; Pryke A.; Fairclough J. P. A. Direct Imaging of the Orientational Dynamics of Block Copolymer Lamellar Phase Subjected to Shear Flow. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 5260–5272. 10.1021/ma3004289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mykhaylyk O. O.; Warren N. J.; Parnell A. J.; Pfeifer G.; Laeuger J. Applications of Shear-Induced Polarized Light Imaging (SIPLI) Technique for Mechano-optical Rheology of Polymers and Soft Matter Materials. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 2016, 54, 2151–2170. 10.1002/polb.24111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orts W. J.; et al. Enhanced Ordering of Liquid Crystalline Suspensions of Cellulose Microfibrils: A Small Angle Neutron Scattering Study. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 5717–5725. 10.1021/ma9711452. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B. Z.; Xu H. Preparation, Alignment, and Optical Properties of Soluble Poly(phenylacetylene)-Wrapped Carbon Nanotubes. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 2569–2576. 10.1021/ma981825k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glatter O.; Kratky O.. Small-Angle X-ray Scattering; Academic Press: London, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Blanazs A.; Verber R.; Mykhaylyk O. O.; Ryan A. J.; Heath J. Z.; Douglas C. W. I.; Armes S. P. Sterilizable Gels from Thermoresponsive Block Copolymer Worms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 9741–9748. 10.1021/ja3024059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding L. A.; Lane J. A.; Derry M. J.; Mykhaylyk O. O.; Armes S. P. Thermo-responsive Diblock Copolymer Worm Gels in Non-polar Solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5790–5798. 10.1021/ja501756h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen J. S.; Gerstenberg M. C. Scattering Form Factor of Block Copolymer Micelles. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 1363–1365. 10.1021/ma9512115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.