Abstract

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a form of major depressive disorder affecting approximately 13% of women worldwide. Unintended pregnancies, reaching close to 50% of the pregnancies in the United States, have become a major health concern. While many physiologic and psychosocial causes have been analyzed, few studies have examined the relationship between unintended pregnancy and symptoms of PPD.

A cross-sectional study was conducted using surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) from 2009 to 2011. The PRAMS population-based random sample included women who have had recent live births and is representative of 78% of the United States population. The chi-squared test was used to examine bivariate associations. Binary logistic regression was utilized to study unadjusted and adjusted associations between PPD and pregnancy intendedness, as well as other demographic and clinical characteristics of mothers in the sample. Multicollinearity in the adjusted model was evaluated using variance inflation factors. Sampling weights were used to account for PRAMS’ complex sampling design.

Of the 110,231 mothers included in the sample, only 32.3% reported desiring the pregnancy at the time of conception. Women with pregnancies categorized as mistimed: desired sooner, mistimed: desired later, or unwanted were 20% (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.2; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1–1.3), 30% (AOR = 1.3; 95% CI: 1.2–1.4), and 50% (AOR = 1.5; 95% CI: 1.3–1.7) more likely to experience symptoms of PPD, respectively, compared to women with desired pregnancies. Other factors found to be associated with experiencing symptoms of PPD were a gestational age of <27 weeks (AOR = 3.1; 95% CI: 2.5–4.0), having a previous history of depression (AOR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.6–2.0), and being abused during or before pregnancy (AOR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.4–2.0).

We found that women with mistimed or unwanted pregnancies were more likely to experience symptoms of PPD. Our findings support the current US Preventive Services Task Force and American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for an integrated approach to screening for depression, aiding in the maximization of intervention and early referral for women at risk for PPD.

Keywords: mental health, postpartum depression, pregnancy intendedness

1. Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD), or depression experienced after pregnancy, is a serious illness that puts the well-being of both mother and baby at risk. It is highly prevalent among new mothers, affecting nearly 13% of women.[1] It is also a highly stigmatized condition, although recent high-profile cases have drawn significant media attention to the issue. Given its stigmatized nature, as well as both the short-term and long-term implications for mother and child, effective screening for PPD by general medical practitioners is an essential public health intervention.

PPD is a term that has suffered from lack of clarity and is not clearly operationally defined. The 2013 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) utilizes a broader term of peripartum depression, encompassing depression in which the onset occurred during or within the first 4 weeks of pregnancy, as a form of major depressive disorder. A person who suffers from a major depressive episode must either have a depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities consistently for at least a 2-week period. A major depressive episode is also characterized by the presence of 5 or more of these symptoms: a depressed mood; markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities; significant unintentional weight loss or gain; insomnia or hypersomnia; agitation or psychomotor retardation; fatigue or loss of energy; feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt; diminished ability to think, concentrate, or make decisions; and recurrent thoughts of death.[2] However, within primary care settings, it is likely not possible to make a formal diagnosis of peripartum depression. For primary care physicians, obstetricians, and pediatricians working with new mothers, attention should be paid to screening for potential symptoms of PPD, such as feeling depressed, hopeless, or slowed down, so that appropriate referrals for mental health services can be made.

Unintended pregnancy is also a serious public health concern in the United States, which has rates higher than most other industrialized nations. It has been estimated that nearly half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended, and poorer women are disproportionately affected.[3] Women who experience unintended pregnancies are less likely to receive adequate prenatal care or breastfeed, and are more likely to engage in unhealthy activities during pregnancy and have low birth weight babies.[3] Unintended pregnancies are described as either unwanted or mistimed. An unwanted pregnancy is defined as occurring when no children or no additional children are wanted by the mother. Mistimed pregnancies include those occurring earlier or later than desired.[3,4]

While many physiologic and psychosocial causes of PPD have been explored, few studies have examined the relationship between pregnancy intendedness and experiencing symptoms of PPD.[5–12] To our knowledge, no such national studies within the United States have been conducted. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between pregnancy intendedness and symptoms of PPD. We explored this association using a nationally representative sample available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS).[13]

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This secondary data analysis utilized data from PRAMS.[13] PRAMS uses a complex survey design in order to capture adequate information from high-risk populations.[14] Forty states and New York City participate in the annual survey, representing 78% of live births in the United States.[13] All women with live births within the surveillance period are eligible for inclusion. Data collected from 2009 to 2011 using the PRAMS Phase 6 Core Questionnaire were included in this study.[15]

Pregnancy intendedness was measured by participants’ answers to the question, “Thinking back to just before you got pregnant with your new baby, how did you feel about becoming pregnant?” Following the definitions utilized by Finer and Zolna,[3] pregnancy intendedness for those answering “I wanted to be pregnant then” was categorized as Desired; “I wanted to be pregnant sooner” as mistimed: desired sooner; “I wanted to be pregnant later” as mistimed: desired later; and “I did not want to be pregnant then or at any time in the future” as unwanted. The outcome of interest was defined by participants’ answers to survey questions related to self-assessed experience with symptoms of PPD. Women were asked if after the birth of their child they felt any of the following symptoms: down, depressed, or sad; hopeless; or slowed down. If the respondent indicated they had experienced any of the 3 symptoms, they were asked to rate the frequency of experiencing the feeling as never, rarely, sometimes, often, or always.[15] Women indicating they sometimes, often, or always experienced any of these symptoms were classified as experiencing symptoms of PPD; those indicating they rarely or never experienced all 3 symptoms were classified as not having PPD. Although the DSM-5 utilizes the broader term of peripartum depression, this study focused solely on depression arising after delivery, excluding women whose depression started prior to delivery.[2]

Potential confounders included maternal age (<20, 20–34, and ≥35 years); ethnicity (Hispanic and non-Hispanic); race (White, Black, and other); marital status (married and unmarried); total annual household income (<$10,000, $10,000–$19,999, $20,000–$49,999, and >$50,000); level of education (less than high school, high school, and more than high school); gestational age at birth (<28, 28–33, 34–36, and ≥37 weeks); medical history of depression (no and yes); abuse during or before pregnancy (no and yes); and presence of stressors in the mother's life (none, 1–2 stressors, 3–5 stressors, and 6 or more stressors). Stressors included: having an ill family member; separation or divorce from partner; recent move; homelessness; respondent lost a job; partner lost a job; arguing with partner more than usual; partner did not desire pregnancy; unable to pay bills; being in a physical fight; respondent or partner went to jail; someone close to the respondent had a problem with drugs or drinking; or someone close to the respondent died.

2.2. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics included examining frequency distributions of the categorical variables and assessing for missing data. We examined bivariate associations using the chi-squared test. Binary logistic regression was utilized to study unadjusted and adjusted associations between PPD and pregnancy intendedness, as well as other demographic and clinical characteristics of mothers in the sample. The adjusted model included maternal age, ethnicity, race, marital status, total household income, level of education, gestational age, medical history of depression, abuse during or before pregnancy, and the presence of stressors in the mother's life. Multicollinearity in the adjusted model was evaluated using variance inflation factors. Sampling weights were used to account for PRAMS’ complex sampling design.[14] A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to assess the statistical significance of estimated odds ratios. Data analysis was performed using Stata 13 (College Station, TX).

2.3. Ethical review

Ethical approval was waived since the analysis was considered nonhuman subjects research by the Florida International University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

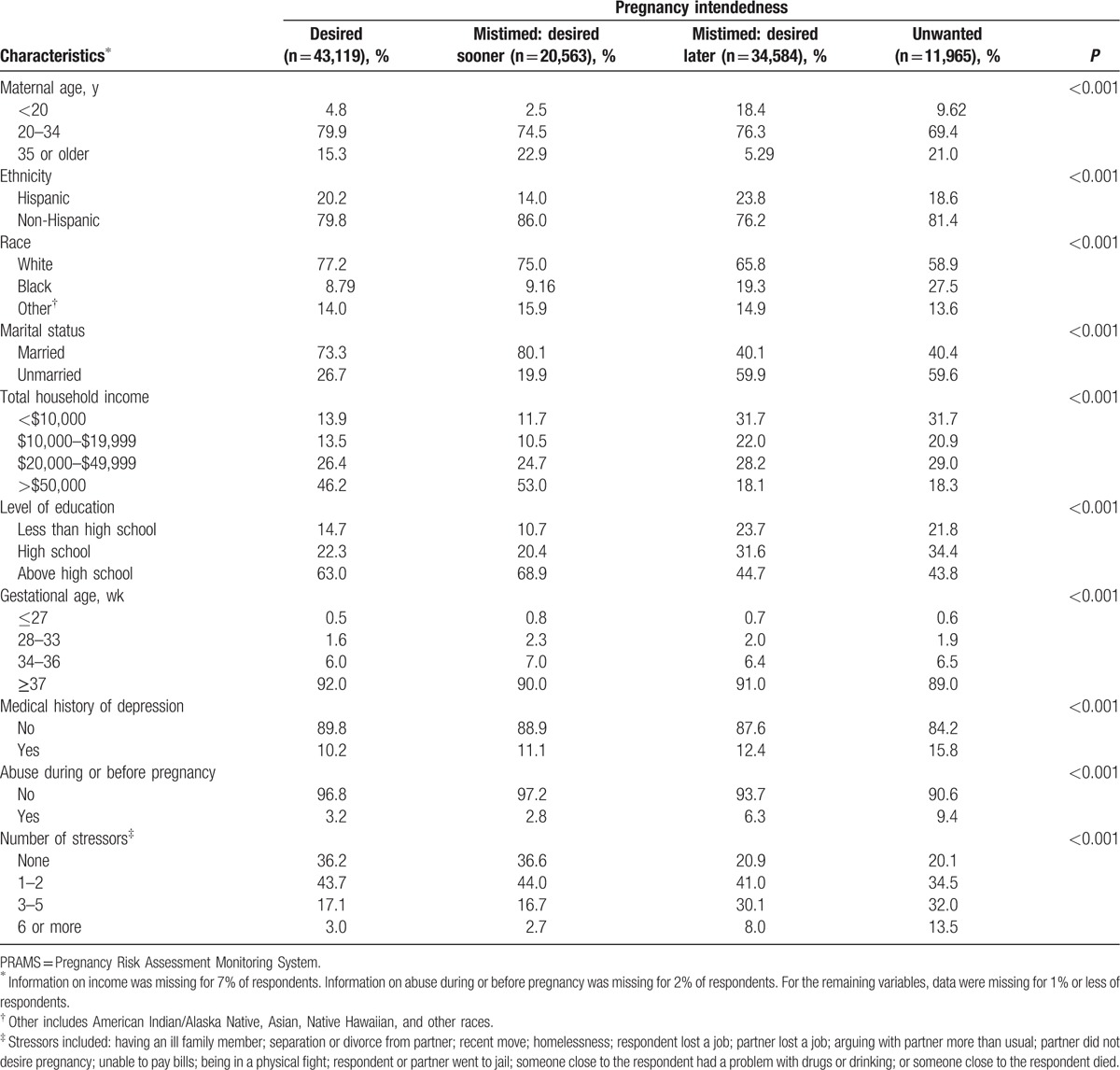

Among the 112,358 women who completed the PRAMS Phase 6 Core Questionnaire, 110,231 provided information related to pregnancy intendedness and were included in this study. Table 1 describes the demographic and clinical characteristics of mothers included in the sample by pregnancy intendedness. Of these, 32.3% had pregnancies categorized as desired; 17.5% had pregnancies categorized as mistimed: desired sooner; 40.1% had pregnancies categorized as mistimed: desired later; and 10.1% had pregnancies categorized as unwanted. All characteristics showed a statistically significant relationship with pregnancy intendedness. Women with pregnancies categorized as mistimed: desired later or unwanted were more likely to be unmarried (P < 0.001), have a total household income of <$10,000 (P < 0.001), have an education level of high school or less (P < 0.001), have a medical history of depression (P < 0.001), report a history of abuse (P < 0.001), and have more stressors (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, by pregnancy intendedness, of mothers responding to the PRAMS Phase 6 Core Questionnaire, 2009 to 2011 (N = 110,231).

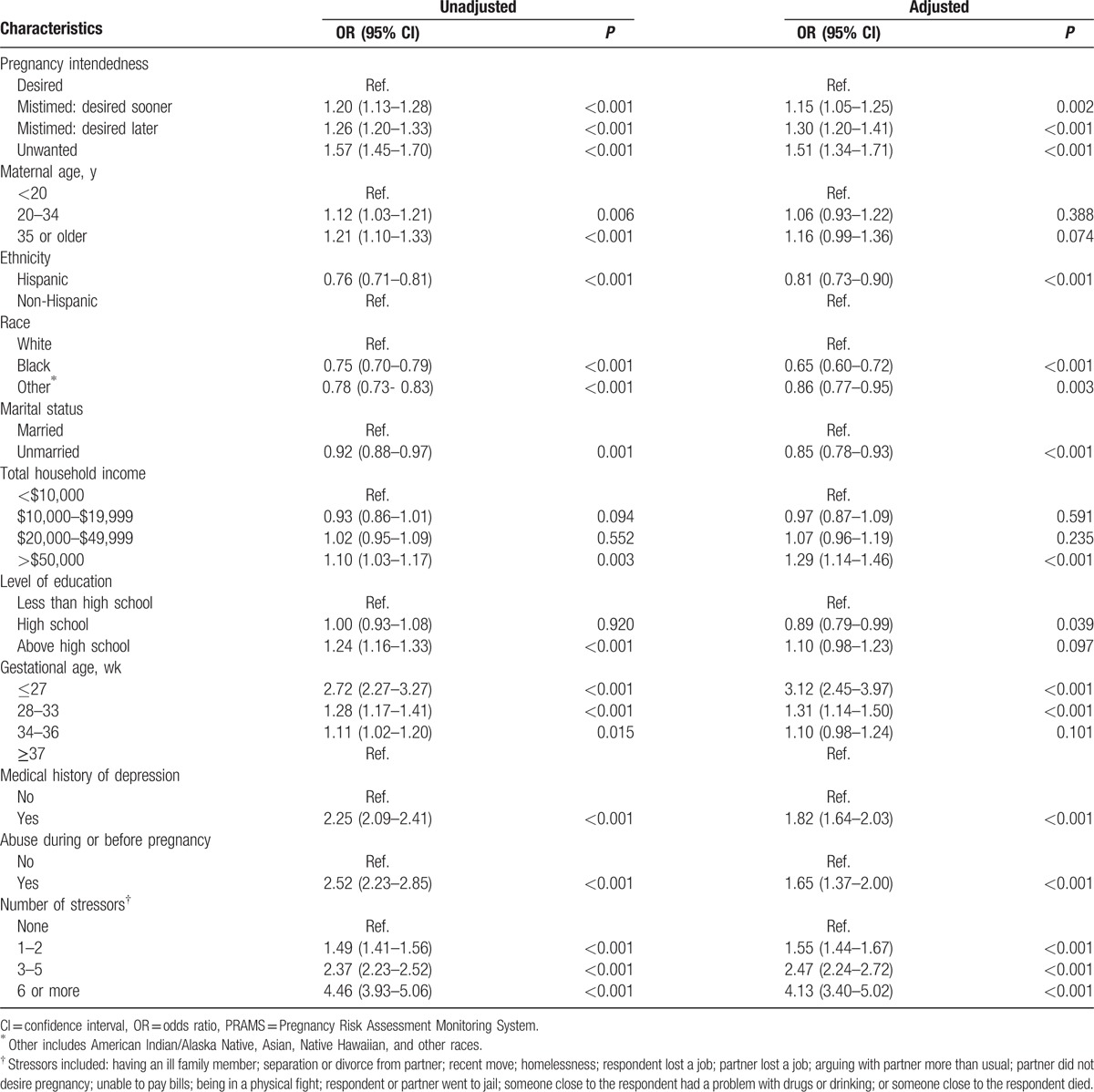

Table 2 shows the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for PPD among mothers surveyed by PRAMS from 2009 to 2011. No multicollinearity was observed in the adjusted model. With any incongruence between intention of pregnancy and time of conception, women were more likely to experience symptoms of PPD; this association remained even after adjustment for confounding variables. Women with pregnancies categorized as mistimed: desired sooner, mistimed: desired later, or unwanted had 1.2 (95% CI: 1.1–1.3), 1.3 (95% CI: 1.2–1.4), and 1.5 (95% CI: 1.3–1.7) times the odds of experiencing symptoms of PPD, respectively, compared to women with desired pregnancies. Other factors found to be associated with experiencing symptoms of PPD were a gestational age of <28 weeks (AOR = 3.1; 95% CI: 2.5–4.0), having a previous history of depression (AOR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.6–2.0), and being abused during or before pregnancy (AOR = 1.6; 95% CI: 1.4–2.0). A dose effect of the number of stressors on the increased odds of PPD symptoms was observed after adjustment. Having 1 to 2 stressors increased the odds of PPD symptoms by half (AOR = 1.5; 95% CI: 1.4–1.7), 3 to 5 stressors more than doubled the odds (AOR = 2.5; 95% CI: 2.2–2.7), and 6 or more stressors quadrupled the odds (AOR = 4.1; 95% CI: 3.4–5.0). Women with household income >$50,000 had 1.3 times the odds of experiencing symptoms of PPD compared to women with household income <$10,000 (AOR = 1.3; 95% CI: 1.1–1.5). Unmarried women were less likely to experience symptoms of PPD (AOR = 0.9; 95% CI: 0.8–0.9). Black women and women of other race were also less likely to experience symptoms of PPD (AOR = 0.7; 95% CI: 0.6–0.7 and AOR = 0.9; 95% CI: 0.8–0.95, respectively). Maternal age of 35 years or older had a borderline significant association with experiencing symptoms of PPD (AOR = 1.2; 95% CI: 1.0–1.4).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and adjusted associations between symptoms of postpartum depression, pregnancy intendedness, and other demographic and clinical characteristics among mothers responding to the PRAMS Phase 6 Core Questionnaire, 2009 to 2011 (N = 110,231).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between pregnancy intendedness and experiencing symptoms of PPD. While other potential risk factors have been investigated, in our review of the literature we found only a few studies exploring the relationship between pregnancy intendedness and symptoms of PPD. To our knowledge, this is the first study utilizing a national sample to explore pregnancy intendedness as a possible risk factor for PPD symptoms. We found a significant association between pregnancy intendedness and PPD symptoms, even after adjusting for several confounders. Women with pregnancies categorized as mistimed: desired sooner, mistimed: desired later, and unwanted had 1.2, 1.3, and 1.5 times the odds of experiencing symptoms of depression, respectively. Our results draw attention to the potential importance of targeted approaches to screen for PPD in women with mistimed or unwanted pregnancies.

Our findings were similar to those of Iranfar et al, Karacam et al, and Cortés-Salim et al, who evaluated pregnancy intendedness as a risk factor for PPD in Iran, Turkey, and Mexico, respectively.[16–18] Iranfar et al found that Iranian women who had unintended pregnancies were at higher risk for PPD compared to women with intended pregnancies.[16] Likewise, Karacam et al observed that Turkish women with unplanned pregnancies experienced a greater number of psychiatric disorders during the early postpartum period compared to those with planned pregnancies, and Cortés-Salim et al reported that women with unplanned pregnancies had higher rates of psycho-emotional disorders compared to those who did not.[17,18]

Beck et al and Robertson et al determined that prenatal depression was a predictor of PPD.[7,9] This study lends further support to that finding; women with a history of depression were approximately twice as likely to suffer from symptoms of PPD when compared to those without a history of depression. Similarly to Robertson et al, we discovered that as the number of stressors increased, the odds of PPD symptoms increased.[9] In respect to maternal age, our study supports the findings of McGuinness et al, who concluded that although not a sole risk factor, maternal age is associated with many challenges in pregnancy which may lead to a higher incidence of PPD.[12] Additionally, our findings were congruent with those of Beck et al, who found 13 significant predictors of PPD, including unplanned/unwanted pregnancy, prenatal depression, life stress, and social support.[7] Our finding that women who were unmarried were slightly less likely to experience symptoms of PPD warrants further investigation. Other studies have examined the quality of the marital relationship as a contributing factor to PPD.[9,19] Our finding may be explained, at least in part, by the fact that we were unable to control for relationship quality. The findings that women of Black and other race had decreased odds of experiencing symptoms of PPD and that higher household income increased the odds is contrary to findings in other studies.[7,20] Complex factors such as awareness and cultural acceptability of reporting symptoms related to PPD may help to explain these findings but were beyond the scope of this analysis, thus requiring further investigation.[21]

One strength of our study is the use of PRAMS data, which was collected in a systematic, standardized manner, and provided a large sample size representative of 78% of live births in the United States.[13] To our knowledge, this is the first study in the literature to utilize PRAMS data to explore the association between pregnancy intendedness and experiencing symptoms of PPD on a national level. Possible limitations include the risk of recall and social desirability bias among respondents, as well as the cross-sectional nature of the data collected. Additionally, the extent to which stressors affected an individual respondent is unknown; PRAMS does not collect information that would help clarify the complicated relationship between the effects of stress on an individual. For this reason, we were unable to weight stressors based on their level of severity for each respondent. Furthermore, our operational definition for symptoms of PPD, based on the frequency the symptoms were experienced, may limit generalizability. To improve screening procedures, future research may include determination of the threshold for the number and frequency of self-reported symptoms that should be considered indicative of the presence of PPD, with appropriate analysis of sensitivity and specificity when comparing to the gold standard of formal psychiatric diagnosis.

We found that women with mistimed or unwanted pregnancies were more likely to experience symptoms of PPD. Our findings encourage physician evaluation of pregnancy intendedness during the patient's prenatal and postpartum office visits. This recommendation is relevant to primary care physicians, obstetricians, and pediatricians who are likely to come in contact with mothers frequently in the weeks following birth. Our findings support the current US Preventive Services Task Force and American Academy of Pediatrics recommendations for an integrated approach to screening for depression with the ultimate goal of intervention and early referral for women at risk for PPD, as well as highlight the need for a quick and accurate diagnostic tool for early detection of PPD.[22–24] Given the potential physical and psychological impact of PPD on both mother and child, particularly for those with low levels of social support, adequate screening for symptoms of PPD is a public health imperative.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the PRAMS Working Group for their feedback.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AOR = adjusted odds ratio, CI = confidence interval, DSM-5 = Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition, MDD = major depressive disorder, PPD = postpartum depression, PRAMS = Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System.

CG and JN contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Breese McCoy SJ. Postpartum depression: an essential overview for the practitioner. South Med J 2011;104:128–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Association, 5th edWashington:2013. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Santelli J, Rochat R, Gilbert B, et al. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2003;35:94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Josefsson A, Angelsi L, Berg G, et al. Obstetric, somatic, and demographic risk factors for postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Goker A, Yanikkerem E, Demet MM, et al. Postpartum depression: is mode of delivery a risk factor? ISRN Obstet Gynecol 2012;2012:616759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res 2001;50:275–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, et al. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception 2009;79:194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, et al. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;26:289–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Davey HL, Tough SC, Adair CE, et al. Risk factors for sub-clinical and major postpartum depression among a community cohort of Canadian women. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:866–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kost K, Landry DJ, Darroch JE. Predicting maternal behaviors during pregnancy: does intention status matter? Fam Plann Perspect 1998;30:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McGuinness TM, Medrano B, Hodges A. Update on adolescent motherhood and postpartum depression. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2013;51:15–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].PRAMS. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/prams/ Accessed January 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [14].PRAMS Methodology. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/prams/methodology.htm Accessed January 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [15].PRAMS Questionnaires. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/prams/questionnaire.htm Accessed January 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Iranfar S, Shakeri J, Ranjbar M, et al. Is unintended pregnancy a risk factor for depression in Iranian women? East Mediterr Health J 2005;11:618–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Karaçam Z, Onel K, Gerçek E. Effects of unplanned pregnancy on maternal health in Turkey. Midwifery 2011;27:288–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cortés-Salim P, González-Barrón M, Romero-Gutiérrez G. Psycho-emotional disorders in women with unplanned pregnancies. Am J Health Res 2014;2:27–32. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Roux G, Anderson C, Roan C. Postpartum depression, marital dysfunction, and infant outcome: a longitudinal study. J Perinat Educ 2002;11:25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Howell EA, Mora PA, Horowitz CR, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in factors associated with early postpartum depressive symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105:1442–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Amankwaa LC. Postpartum depression, culture and African-American women. J Cult Divers 2003;10:23–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for depression in adults us preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2016;315:380–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Earls MF. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health American Academy of Pediatrics. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2010;126:1032–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP publications reaffirmed or retired. Pediatrics 2015;135:e1105–6. [Google Scholar]