Abstract

Rationale:

Stellate ganglion blocks have been shown to provide effective pain relief in a number of different conditions, but no one had reported stellate ganglion blocks for the treatment of epileptic pain. We describe a case report of the successful use of stellate ganglion block in the treatment of epileptic pain in the patient.

Patient concerns:

A 8-year-old girl who had experienced severe paroxysmal pain in her right upper limb.

Diagnoses:

She was diagnosed as drug-resistant partial epilepsy.

Interventions:

The patient received stellate ganglion blocks with lidocaine for 2 courses with 2 weeks in a course of treatment and oral carbamazepine once a day.

Outcomes:

Carbamazepine dosage gradually tapered until stop and epileptic pain attacks become less and less, eventually disappear.

Lessons:

Stellate ganglion block may be an effective treatment of intractable partial epilepsy. However, more research is now needed to verify the validity.

Keywords: carbamazepine, epileptic pain, lidocaine, stellate ganglion blocks

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is a recurrent neurological disorder characterized by irregular, unprovoked epileptic seizures. Pain is a rare subjective symptom during a seizure.[1] We reported the case of a normal developmentally child who experienced severe ictal pain as the initial symptom of partial epilepsy. And, unfortunately, the child developed into drug-resistant epilepsy. We experimented with use of stellate ganglion block in the treatment of epileptic pain in the child.

2. Case report

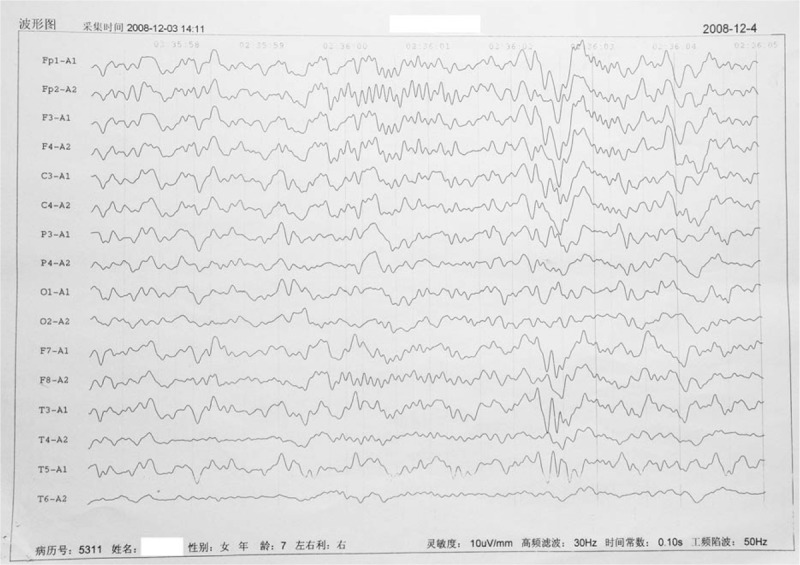

A 8-year-old girl who had experienced severe paroxysmal pain in her right upper limb with ictal electroencephalographic abnormalities for over 4 years. As paroxysmal pain attacked, Ambulatory electroencephalography (AEEG) showed spike-and-wave discharge in the left temporal area (Fig. 1). Head MRI images, blood, urine, and stool tests were normal. Epilepsy experts diagnosed as focal epilepsy. The pain was partially responsive to carbamazepine in early stages, but develop drug-resistant epilepsy. The patient received carbamazepine 0.7 g once a day. The pain in her right upper limb has 10 or more episodes a day, each lasting of 3 to 10 seconds. Finally, she was recommended to the pain department.

Figure 1.

Ambulatory electroencephalography (AEEG) showed spike-and-wave discharge in the left temporal area when epileptic pain attacks arisen. AEEG = ambulatory electroencephalography.

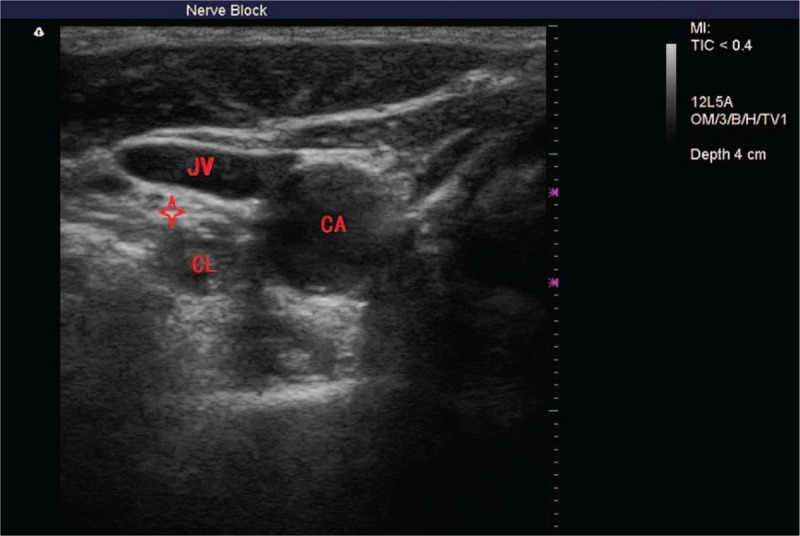

The patient received a stellate ganglion blocks with 5 mL of 1% lidocaine under ultrasound guidance (Fig. 2) and oral carbamazepine 0.7 g once a day. The injection sites alternate between left and right stellate ganglion daily. Stellate ganglion blocks were suspended because epileptic pain attacks become more frequent (15 episodes a day) on the 5th day after therapy. Then, 2 weeks later, epileptic pain attacks become less frequent (5–6 episodes a day) and pain degree was alleviated. We resumed stellate ganglion blocks for 2 weeks. After stellate ganglion blocks, epileptic pain attacks become 3 episodes a day and carbamazepine dosage reduced from 0.7 g to 0.4 g once a day. In the following 2 weeks, carbamazepine dosage reduced from 0.4 g to 0.2 g once a day without the changes of epileptic pain attacks. After a 2-week hiatus, we resumed stellate ganglion blocks for 2 weeks again and discontinued carbamazepine. Until now, epileptic pain has not attacked after the last stellate ganglion block.

Figure 2.

Ultrasonogram displayed the position of stellate ganglion and adjacent structures. CA = carotid atery, CL = Collilongus, JV = jugular vein, red star = stellate ganglion.

3. Discussion

Despite the fact that more than 10 different antiepileptic drugs are now available, about 30% of patients with epilepsy continue to have inadequate seizure control.[2] Patients with drug-resistant epilepsy often experience various side effects of drug therapy, and the failure to control seizures has the risk of devastating psychosocial, economic, and health consequences.[3] Stellate ganglion blocks have been shown to provide effective pain relief in a number of different conditions,[4] but no one had reported stellate ganglion blocks for the treatment of epileptic pain. The patient received intermittent stellate ganglion blocks during 2 months. It has been 8 years since the patient received the last stellate ganglion block and epileptic pain has not attacked so far.

Stellate ganglion is part of the sympathetic nervous system and supply the head, neck, chest, or arm.[5] Stellate ganglion blocks may reduce the sympathetic nerve activating the pain sensitive nerves and reduce the pain.[6] The parasympathetic tone of head is relatively predominant during a stellate ganglion block. An interesting point: vagus nerve stimulation is an effective therapy for intractable epilepsy.[7,8] Although it remains unclear how vagus nerve stimulation will work, 1 possibility is that the parasympathetic nervous system was activated. We think the stellate ganglion block and vagus nerve stimulation may have similar neuromodulatory effects. So we tried to treat the intractable epilepsy through the stellate ganglion block.

4. Conclusion

The stellate ganglion block may be an effective treatment of intractable partial epilepsy. However, more research is now needed to verify the validity.

5. Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and patients’ guardians.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AEEG = ambulatory electroencephalography, CA = carotid artery, CL = collilongus, JV = jugular vein.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Trevathan E, Cascino GD. Partial epilepsy presenting as focal paroxysmal pain. Neurology 1988;38:329–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Englot DJ, Rolston JD, Wright CW, et al. Rates and predictors of seizure freedom with vagus nerve stimulation for intractable epilepsy. Neurosurgery 2016;79:345–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dalic L, Cook MJ. Managing drug-resistant epilepsy: challenges and solutions. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:2605–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Marples IL, Atkinson RE. Stellate ganglion block. Pain Reviews 2001;8:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- [5].McDonnell JG, Finnerty O, Laffey JG. Stellate ganglion blockade for analgesia following upper limb surgery. Anaesthesia 2011;66:611–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Swissa M, Zhou S, Tan AY, et al. Atrial sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve sprouting and hyperinnervation induced by subthreshold electrical stimulation of the left stellate ganglion in normal dogs. Cardiovasc Pathol 2008;17:303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Attenello F, Amar AP, Liu C, et al. Theoretical basis of vagus nerve stimulation. Prog Neurol Surg 2015;29:20–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fanselow EE. Central mechanisms of cranial nerve stimulation for epilepsy. Surg Neurol Int 2012;3:S247–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]