Abstract

Rationale:

Angiokeratomas are the earliest manifestation of Fabry disease (FD), and the extent of their appearance is related to disease severity. Angiokeratomas are mostly found on cutaneous regions.

Patient concerns, diagnoses, interventions, and outcomes:

Here we report an FD patient with widespread gastrointestinal angiokeratomas who developed life-threatening bleeding following anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation.

Lessons:

Careful observation for gastrointestinal bleeding is warranted for patients on anticoagulation with extensive cutaneous angiokeratomas. Furthermore, our experience suggests that surveillance is needed to assess the prevalence and extent of gastrointestinal angiokeratomas in patients with FD.

Keywords: angiokeratoma, bleeding, Fabry disease, gastric

1. INTRODUCTION

Fabry disease (FD; OMIM 301500) is caused by a deficiency in α-galactosidase A (GLA; EC 3.2.1.22)[1] and manifests as either the classic or variant phenotype based on residual GLA activity. As it is inherited in an X-linked manner, in male patients, classic FD manifests as acroparesthesia and angiokeratomas in childhood that subsequently cause life-threatening complications such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, chronic renal failure, and cerebral vascular events in their second to fifth decades of life.[1]

The angiokeratomas of FD are small, raised, dark-red spots caused by damage to the vascular endothelial cells in the dermis. Angiokeratomas are one of the earliest and most common signs of FD, and they are detected in 66% of males and 36% of females with FD.[2] Their extent may be related to the clinical severity of FD.[3] In FD, angiokeratomas are mostly found on cutaneous regions, including the lower back, buttocks, groin, and upper thighs.[1] However, mucosal lesions are observed on the lips or tongue of some patients.[3] Here, we report a male patient with classic FD who had widespread angiokeratomas in the gastrointestinal mucosa. He experienced a life-threatening bleeding episode from the angiokeratomas in the gastric mucosa during anticoagulation therapy after cardioversion for atrial fibrillation. This is the first reported case of FD with extensive angiokeratomas in the gastrointestinal mucosa.

2. CASE DESCRIPTION

The patient had been experiencing neuropathic pain in his hands and feet since early childhood. Multiple angiokeratomas were observed on his trunk, groin, and upper thigh. He had proteinuria and renal insufficiency at 30 years of age and received a renal transplantation at 34 years of age. In addition, he had bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, bilateral cornea verticillata, and mild concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. FD was suspected based on the result of a histological examination of the kidneys. GLA activity in peripheral leukocytes was 0 nmol h−1 mg−1 of protein (reference, 49 ± 20 nmol h−1 mg−1 of protein). Sequencing of the GLA gene in genomic DNA from peripheral white blood cells showed a pathological mutation, c.334C>T (p.Arg112Cys). He had been receiving enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with agalsidase-β (Fabrazyme; Genzyme–a Sanofi company, Cambridge, MA) at a dose of 1 mg/kg every other week since 40 years of age. At initiation of ERT, his plasma Gb3 level was 10 μg/mL (reference range, 3.9–9.9 μg/mL), the glomerular filtration rate was 58 mL/min·1.73 m2, and left ventricular mass was 126 g/m2; after 10 years of therapy; these values were 5.5 μg/mL, 38 mL/min·1.73 m2, and 126 g/m2, respectively. However, the angiokeratomas were not remarkably decreased in size or number and were still growing extensively on his trunk, groin, and upper thigh (Fig. 1C). At 50 years of age, sustaining atrial fibrillation was detected at an annual cardiological evaluation (Fig. 1A). After 2 months of antiarrhythmic and anticoagulant treatment with amiodarone and dabigatran, respectively, cardioversion was performed, and the atrial fibrillation was successfully converted to a sinus rhythm without complication (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, amiodarone and dabigatran were prescribed to repress the development of arrhythmia and thrombus formation, respectively. However, after 3 months of anticoagulation therapy, he developed massive hematemesis and melena, so he visited an emergency department. Upon arrival, his blood pressure and heart rate were 118/82 mm Hg and 82 beats/min, respectively. Laboratory findings, including complete blood count, chemical battery, and coagulation battery, were normal except for an abrupt decrease in hemoglobin, from 12.3 to 7.7 g/dL. Emergent esophagogastroduodenoscopy revealed multiple angiokeratomas from the base of his tongue to the duodenum (Fig. 1D). Active bleeding was observed from the angiokeratomas in the cardia of the stomach (Fig. 1E), which was successfully stopped with argon plasma coagulation.[4] After discharge from the emergency department, administration of dabigatran was discontinued, and an antiplatelet agent (clopidogrel) was prescribed instead. For 10 months thereafter, he did not experience further gastric bleeding.

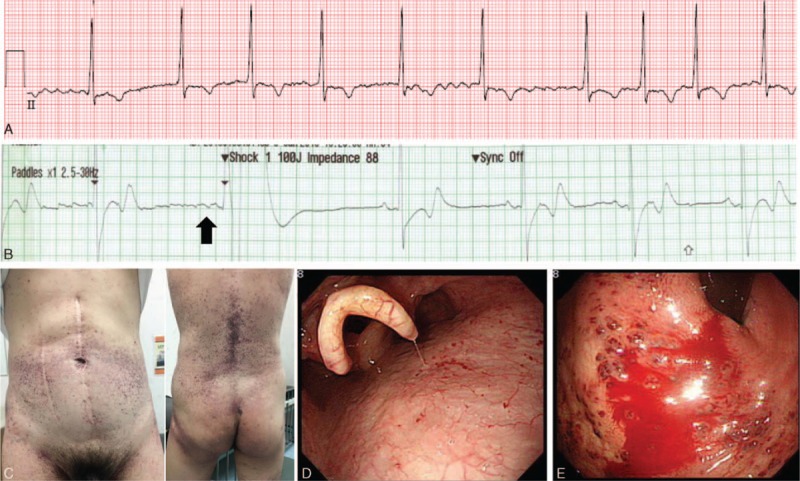

Figure 1.

(A) Atrial fibrillation at 49 years of age. (B) Cardioversion (100 J) converted atrial fibrillation to a sinus rhythm (black arrow). (C) Extensive angiokeratomas on the trunk, back, and thigh after 10 years of enzyme replacement therapy. (D) Multiple angiokeratomas emerging from the base of the tongue to the duodenum. (E) Active bleeding in the gastric cardia.

3. DISCUSSION

Cardiac arrhythmia or ischemic cerebrovascular diseases are major complications of FD, occurring in 27% to 42% and 13% to 25% of patients, respectively.[5,6] Although anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapies are required in these conditions to prevent thromboembolic events, the risk of severe gastrointestinal bleeding has not been assessed in FD.

Although perioral lesions have been frequently reported in FD, extensive angiokeratomas in the gastrointestinal mucosa have rarely been reported. To date, only 1 case has been described, in which the patient had multiple angiokeratomas in the gastric and small intestinal mucosae that were incidentally found during a pretransplantation evaluation.[7,8] The patient did not experience severe gastrointestinal bleeding. Whether angiokeratomas in the gastrointestinal tract are at high risk of bleeding under anticoagulation medications is unclear. However, considering that angiokeratomas consist of vascular proliferation in the dermis and are filled with erythrocytes,[3] the soft and thin gastric and intestinal mucosal barriers overlying the angiokeratomas appear to be easily injured by mechanical or chemical trauma. Although ERT has been shown to help reduce the extent of angiokeratomas in some patients,[9] its effect has not been described in a large patient cohort. In our case, no remarkable changes were observed, and the patient still had an extensive distribution of angiokeratomas despite 10 years of ERT. Thus, our case report indicates that careful observation for gastrointestinal bleeding is required in FD patients receiving anticoagulation therapy when they exhibit extensive cutaneous angiokeratomas. Whether detailed endoscopic evaluation for angiokeratomas in the gastrointestinal tract is warranted before initiation of anticoagulation in FD patients needs to be clarified. However, such an evaluation appears judicious in FD patients with extensive dermal angiokeratomas because extensive gastrointestinal angiokeratomas may also exist, as was observed in our patient. Further evaluation is required to assess the overall prevalence of gastrointestinal angiokeratomas in a large cohort of patients with FD. Moreover, the selection of either an anticoagulant or an antiplatelet agent should be carefully determined in FD patients because dabigatran, similar to warfarin, confers a higher risk of life-threatening bleeding events than antiplatelet agents.[10] A recent systematic review indicates that administration of another anticoagulant, apixaban, does not confer an increased bleeding risk like dabigatrin.[11] Therefore, in FD patients who require anticoagulation, apixaban may be a preferred anticoagulant, and antiplatelet agents should be considered as an alternative.

4. INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent was obtained from the patient regarding the reporting and publication of this case report. Because it was not a clinical trial and no off-label drugs were used, the ethical approval is not necessary for this case report.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ERT = enzyme replacement therapy; FD = Fabry disease; GLA = α-galactosidase A.

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology (NRF-2016M3A9B4915706).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Desnick RJ, Ioannou YA, Eng CM. Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D. α-Galactosidase a deficiency: Fabry disease. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease 8th ed.New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. 3733–75. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Orteu CH, Jansen T, Lidove O, et al. Fabry disease and the skin: data from FOS, the Fabry outcome survey. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:331–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Zampetti A, Orteu CH, Antuzzi D, et al. Angiokeratoma: decision-making aid for the diagnosis of Fabry disease. Br J Dermatol 2012;166:712–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Oh HJ, Cho YK, Lee HH. Bleeding angiokeratomas in Fabry disease treated with argon plasma coagulation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:e129–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Germain DP. Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010;5:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ginsberg L. Mehta AB, Beck M, Sunder-Plassmann G. Nervous system manifestations of Fabry disease: data from FOS-the Fabry outcome surgery. Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 years of FOS. Oxford: PharmaGenesis; 2006;227-323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Baccaglini L, Schiffmann R, Brennan MT, et al. Oral and craniofacial findings in Fabry's disease: a report of 13 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;92:415–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Kouvaras SN. Endoscopic images in Fabry disease. Ann Gastroenterol 2012;25:354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Furujo M, Kubo T, Kobayashi M, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy in two Japanese siblings with Fabry disease, and its effectiveness on angiokeratoma and neuropathic pain. Mol Genet Metab 2013;110:405–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Riley TR, Gauthier-Lewis ML, Sanchez CK, et al. Evaluation of bleeding events requiring hospitalization in patients with atrial fibrillation receiving dabigatran, warfarin, or antiplatelet therapy. J Pharm Pract 2016;doi:10.1177/0897190016630408 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Holster IL, Valkhoff VE, Kuipers EJ, et al. New oral anticoagulants increase risk for gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2013;145:105–12. e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]