Abstract

The most effective vaccine candidate of malaria is based on the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein (CSP), a major surface protein implicated in the structural strength, motility, and immune evasion properties of the infective sporozoites. It is suspected that reversible conformational changes of CSP are required for infection of the mammalian host, but the detailed structure and dynamic properties of CSP remain incompletely understood, limiting our understanding of its function in the infection. Here, we report the structural and mechanical properties of the CSP studied using single-molecule force spectroscopy on several constructs, one including the central region of CSP, which is rich in NANP amino acid repeats (CSPrep), and a second consisting of a near full-length sequence without the signal and anchor hydrophobic domains (CSPΔHP). Our results show that the CSPrep is heterogeneous, with 40% of molecules requiring virtually no mechanical force to unfold (<10 piconewtons (pN)), suggesting that these molecules are mechanically compliant and perhaps act as entropic springs, whereas the remaining 60% are partially structured with low mechanical resistance (∼70 pN). CSPΔHP having multiple force peaks suggests specifically folded domains, with two major populations possibly indicating the open and collapsed forms. Our findings suggest that the overall low mechanical resistance of the repeat region, exposed on the outer surface of the sporozoites, combined with the flexible full-length conformations of CSP, may provide the sporozoites not only with immune evasion properties, but also with lubricating capacity required during its navigation through the mosquito and vertebrate host tissues. We anticipate that these findings would further assist in the design and development of future malarial vaccines.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy (AFM), malaria, plasmodium, single-molecule biophysics, structural biology, NANP, circumsporozoite protein (CSP), force spectroscopy, proline-rich protein, sporozoite, malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, NANP repeats, proline-rich peptides

Introduction

Malaria remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality throughout the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report, there were an estimated 214 million new cases of malaria and 438 thousand deaths due to malaria alone in 2015 (1). The failure to control the disease effectively stems from pesticide resistance of mosquitoes, drug resistance of malaria parasites, and the lack of an effective vaccine against malaria. At present, the most successful malaria vaccine on trial is RTS,S, which makes use of domains of the circumsporozoite protein (CSP),3 which is the most abundant surface protein of the infective sporozoites of Plasmodium species (2–5).

Sporozoites are the infective stage for the vertebrate host and are therefore the appropriate target for a malaria vaccine. The CSP, expressed exclusively in the sporozoite stage, was shown to be the target of protective antibodies (6, 7). Early studies on CSP established the presence of a centrally located immunogenic repeat region in the protein from all species of Plasmodium (7, 8). It was demonstrated that the central repeat domain of the CSP was the variant and immunodominant domain, with about 90% of the protective antibodies reacting against the repeat domain, with only a small response observed for the flanking regions (9). Simian malaria such as Plasmodium knowlesi (10) and Plasmodium cynomolgi (11, 12), as well as the human malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax (13, 14), exhibited huge diversity in the repeat sequences of CSP among different strains of these Plasmodium species, but so far all Plasmodium falciparum strains tested show the presence of NANP repeat sequences, indicating its value as a vaccine candidate epitope (3, 15).

Gene knock-out studies in P. falciparum have demonstrated that CSP is required for the structural development of sporozoites (16). A recent study demonstrated that the repeat region is also critically required for sporozoite formation and maturation (17). Other than the structural requirement of CSP for sporozoites, in the human host, it is functionally involved in hepatocyte invasion by the parasite, as antibodies directed against CSP prevented sporozoite invasion into hepatocytes (18–20). The gliding motility of the sporozoites is also vital for infectivity (20–22). Sporozoites are introduced subcutaneously, and an invasive sporozoite has to squeeze in through the endothelial cell layer before finally infecting a hepatocyte after traversing through Kupffer cells and several hepatocytes (23–25). These observations raise some important questions: 1) How does the sporozoite protect itself against the mechanical and frictional forces operative during such journeys involving several cell penetrations? 2) Does CSP, which forms a dense coat on the surface of the sporozoites, provide some mechanical buffer for such forces? CSP repeats are immunodominant and form immunoevasive cross-reactive domains that elicit a T-cell-independent immune response (8, 26). The immunodominant nature of the CSP repeat region would predict that these would be the majorly exposed domains on the sporozoite.

Although the CSP has been studied for over three decades, and is the only parasite protein used in the RTS,S vaccine (the only malaria vaccine under trial so far), very little is known regarding CSP structure. The study of structural and dynamical properties of CSP has been hampered due to the lack of crystal structure, and so far only a structure of (NANP)3 from the central repeat region has been assessed through NMR studies (27, 28). The C-terminal structure is better predicted as it contains the thrombospondin type 1 repeat (TSR) domain, whereas no structure could be obtained for the N-terminal domain (29, 30). CSP is proposed to have a rod-like structure anchored at the C terminus (31). Recent studies have also suggested that CSP undergoes reversible conformational changes, between an “open (or non-adhesive)” state and a “collapsed (or adhesive)” state, before the sporozoite invades a hepatocyte (18, 32). It was proposed that mechanical force might regulate the conformational change from “collapsed” to “open,” although the force required for such a force-induced change remains to be measured. How divergent can such conformations of repeat region or the terminal domains of CSP be? With the idea that a measurement of the strengths of the repeat region and the internally folded domains of CSP would provide an insight into the dispersion of such structures, we prepared tagged P. falciparum CSP (sandwiched between (I27)3 units) and studied the protein using single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS) (33). We observed that the NANP repeat region (CSPrep) displayed flexibility and heterogeneity in its structure, whereas the near full-length version without the terminal hydrophobic residues (CSPΔHP) exhibited distinctly folded domains with mechanically weak interdomain interactions.

Results

Polyprotein Construction of Malarial CSP

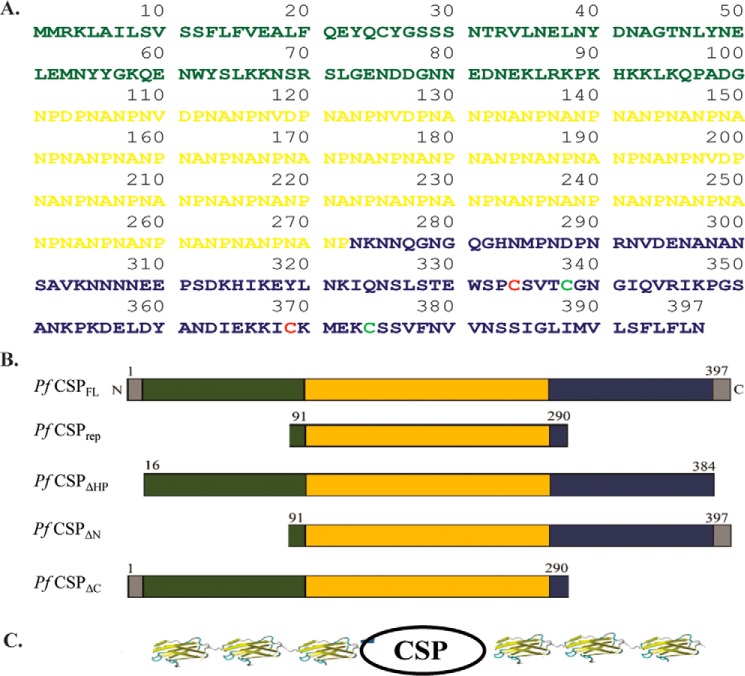

CSP from P. falciparum is a 397-amino acid protein containing an N-terminal signal peptide, a C-terminal TSR domain and GPI anchor peptide, and an NANP repeat region in the middle (Fig. 1). The NANP repeat region used in our study consists of 172 residues (i.e. 101–272 in the protein sequence), mostly composed of NANP repeats (asparagine, 47%; proline, 25.6%; alanine, 22%; aspartate, 3%; valine, 2.4%). Such proline-rich regions, for example, PEVK segments that are rich in proline, glutamate, valine, and lysine of the muscle protein titin, are found to have unique mechanical properties suited for their environment (34, 35). In this study, we cloned the full-length CSP (CSPFL), the CSPrep, the CSPΔHP, and the N- and C-terminal deletion constructs (Fig. 1B). The polyproteins used in this study were constructed using these CSP variants and the I27 domain from the I-band of the giant muscle protein titin (36, 37). Each CSP is flanked at both termini by three I27 domains to construct the polyproteins (I27)3-CSP-(I27)3, where the I27 domain would provide a molecular fingerprint in the SMFS experiments (37, 38). The details of the polyprotein construction, expression, and purification are given under “Experimental Procedures.” The expressed CSPFL was largely aggregated, and a small amount of soluble protein could be subjected to the SMFS study, but the N- and C-terminal deletion proteins were not soluble at all. The CSPrep and the CSPΔHP polyproteins were largely soluble, and the purified proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting techniques using anti-(NANP)5 antibodies (Fig. 2) and were used in SMFS studies.

FIGURE 1.

Sequence and constructs of P. falciparum CSP used in SMFS experiments. A, protein sequence of P. falciparum CSP, which has an N-terminal domain (shown in green) and a C-terminal domain containing TSR domain and GPI anchor peptide (blue). The repeat region at the center (residues 101–272) has 43 NANP repeats (shown in orange). The cysteines of the two disulfide bonds (Cys334–Cys369, Cys338–Cys374) in the TSR domain are marked with different colors. B, schematic representation of different CSP constructs chosen for mechanical study: P. falciparum (Pf) CSPFL, CSPrep, CSPΔHP, CSPΔN, and CSPΔC. C, schematic representation of CSP chimeric polyproteins along with the I27 domain, (I27)3-CSP-(I27)3, for SMFS experiments. Here CSP represents: CSPFL, CSPrep, CSPΔHP, CSPΔN, or CSPΔC. The I27 structure used in the graphic is taken from Protein Data Bank (PDB) code: 1TIT.

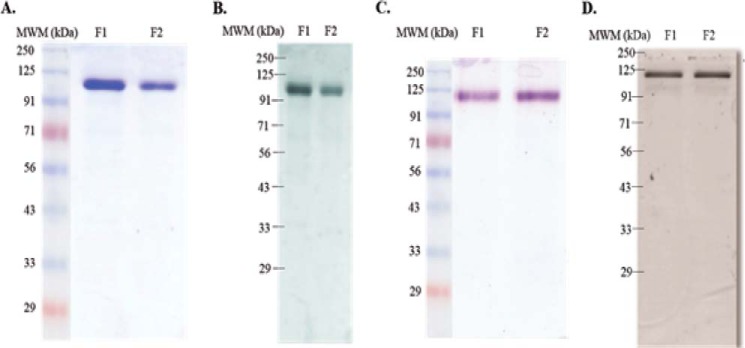

FIGURE 2.

Purification of CSP chimeric polyproteins confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. A, Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained gel of the tagged (I27)3-CSPrep-(I27)3 protein purified by FPLC (lanes F1 and F2). MWM, molecular weight markers. B, Western blot of (I27)3-CSPrep-(I27)3 using anti-(NANP)5 monoclonal antibody (lanes F1 and F2). C, Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained gel of the tagged (I27)3-CSPΔHP-(I27)3 protein purified by FPLC (lanes F1 and F2). D, Western blot of (I27)3-CSPΔHP-(I27)3 using anti-(NANP)5 monoclonal antibody (lanes F1 and F2).

SMFS Studies on (I27)3-CSPrep-(I27)3 Polyproteins

The polyproteins in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) were used for SMFS pulling studies. A pulling velocity of 1000 nm/s was kept constant for all the experiments. A representative force-versus-extension (FX) trace of (I27)3-CSPrep-(I27)3 polyprotein (given by 60% population) is shown in Fig. 3A. The FX trace has a sawtooth pattern of eight force peaks with peak force in the range 100–250 pN. The force peaks were fitted with a worm-like chain (WLC) model of polymer elasticity, and the increment in contour length (ΔLc) followed by the force peaks was estimated (39). In the FX trace, the ΔLc followed by the force peaks 2–7 is ∼27 nm, and their peak force is ∼200 pN, which are characteristic properties of the I27 domain (36–38). The last force peak in the FX trace is due to the detachment of the molecule from the cantilever tip or from the substrate. Hence, six I27 domains in the polyprotein serve as a molecular fingerprint of single molecules, and observing more than four force peaks of I27 in FX traces ensures that the sandwiched CSP domains have been subjected to the pulling force (37, 38). Therefore, FX traces containing at least four I27 unfolding force peaks were considered for data analysis. Once the I27 signatures have been identified in the FX trace, the remaining features are assigned to the mechanical unraveling of the CSP protein.

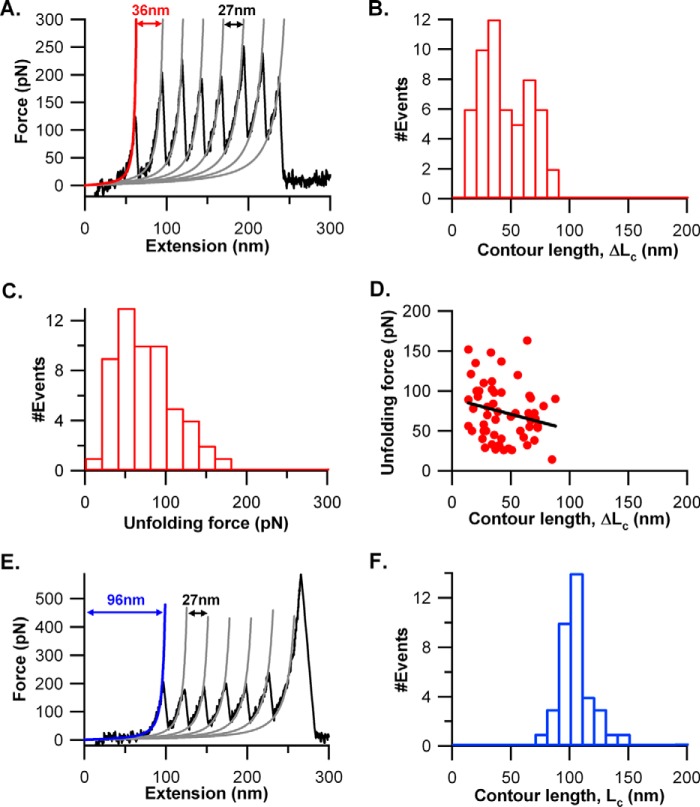

FIGURE 3.

Mechanical unfolding of (I27)3-CSPrep-(I27)3 in SMFS experiments. A, representative FX trace of the protein at a pulling speed of 1000 nm/s. 60% of traces showed a distinct force peak for the CSPrep. The force peaks in the trace were fitted to the WLC model of polymer elasticity (shown as solid lines in red and gray). The force peaks with a contour length change (ΔLc) ∼27 nm correspond to the unfolding of I27 (colored in gray), whereas the force peak with ΔLc ∼36 nm corresponds to CSPrep (colored in red). B, distribution of ΔLc (44 ± 20 nm, average ± S.D.), n = 55, of CSPrep upon unfolding. C, distribution of the unfolding forces of CSPrep. The unfolding force of CSPrep is 73 ± 35 pN (average ± S.D.), n = 55. D, scatter plot of ΔLc and unfolding force of CSPrep. The line represents a linear fit with correlation coefficient, r = −0.21 (p value = 0.12). E, the FX behavior of 40% of cases where CSPrep does not yield any discernible force peak but the FX traces have a long spacer preceding the unfolding sawtooth pattern of I27. F, Lc of the spacer preceding the first I27 unfolding force peak is 104 ± 13 nm (average ± S.D.), n = 37.

In Fig. 3A, we assigned the force peak in the beginning of the FX trace, preceding the I27 sawtooth pattern, to the mechanical unraveling of CSPrep. The ΔLc of the peak is 36 nm, and its rupture force is ∼100 pN. This force is much lower than that of the I27, and hence, it precedes the I27 sawtooth pattern in the FX trace. Surprisingly, the ΔLc of CSPrep is much lower than the expected value from the unraveling of NANP repeats ∼76 nm (200 aa × 0.38 nm/aa) (40). In Fig. 3A, the ΔLc of 36 nm means that ∼20 NANP repeats are compliant and unraveled without any resistance, and the remaining ∼23 NANP repeats have resisted stretching force of ∼100 pN before their rupture, giving rise to a 36-nm elongation after the force peak. The distributions of the rupture forces (73 ± 35 pN) and the ΔLc (44 ± 20 nm) obtained from 55 molecules are given in Fig. 3, B and C. We also made a scatter plot, looking at the correlation between the unfolding force and ΔLc of CSPrep (Fig. 3D). We found no significant correlation (correlation coefficient, r = −0.21, and the p value associated with this correlation is 0.12), ruling out any dependence between the unfolding force and ΔLc. These unfolding force and ΔLc histograms of CSPrep are much broader than those of the I27 domain (rupture force = 205 ± 23 pN and ΔLc = 27.1 ± 0.4 nm; see supplemental Fig. S1). A typically folded domain with a well defined structure such as I27 would give a narrow distribution of ΔLc. The broader width of ΔLc for CSPrep suggests conformational heterogeneity in NANP repeat structures as compared with any well folded globular proteins such as I27. It also means that the size of the mechanically resistant structures varies because some of the NANP repeats of CSPrep have conformations that require 10–180 pN force to unravel, whereas other NANP repeats are mechanically compliant and unravel prior to the resisting NANPs (Fig. 3A). This composition varies from molecule to molecule, giving rise to a broader ΔLc (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, we performed Monte Carlo simulations to see whether the observed ΔLc distribution of CSPrep in Fig. 3B is compatible with a distributed composition of NANP repeats in a mechanically resistant form (see supplemental Fig. S2). Based on the experimentally observed 60% population of CSPrep (43 NANP repeats), which exhibited mechanical resistance, we assumed a probability of 0.6 for a given NANP repeat to be in mechanical resistant conformation. The observed broad distribution of 17–35 repeats in the resistant conformation from the Monte Carlo simulations is in support of the experimentally observed broad ΔLc distribution of CSPrep (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S2).

Heterogeneity of CSPrep Conformations

The type of FX trace shown in Fig. 3A is only given by 60% of the molecules. The remaining 40% of the molecules have FX traces as shown in Fig. 3E, where CSPrep did not give any discernible force peak in the FX trace. These FX traces have only force peaks of I27 (regular sawtooth pattern), with a long spacer preceding the I27 sawtooth pattern. We measured the spacer length (Lc) to be 104 ± 13 nm, as shown in Fig. 3F. This long spacer suggests that CSPrep has been unraveled without any mechanical resistance. We compared the elongation in CSPrep (i.e. spacer length) with the corresponding spacer length of the I27 heptamer, (I27)7, shown in Fig. 4. In the case of (I27)7, it is 45 ± 16 nm as compared with CSPrep, which shows 104 ± 13 nm. The difference in the spacer length between these two cases is ∼60 nm, which is coming from the mechanical unraveling of the CSPrep. Overall, the CSPrep mechanical properties suggest that the structure of 43 NANP repeats is conformationally heterogeneous wherein 40% of cases do not require force (or <10 pN) to mechanically unravel them, and in 60% of cases, some of the 43 NANP repeats have a structure that is mechanically resistant, but nevertheless unfolds at weak forces.

FIGURE 4.

Mechanical unfolding of (I27)7 in SMFS experiments. A, representative FX trace of the (I27)7 protein at a pulling speed of 1000 nm/s. B, Lc of the first I27 force peak is 45 ± 16 nm (average ± S.D.), n = 54.

Complexity in the Mechanical Properties of (I27)3-CSPΔHP-(I27)3

We tried pulling experiments on the full-length CSP polyprotein (I27)3-CSPFL-(I27)3. This protein often aggregated after purification, and we could not get single-molecule FX traces with 4–6 force peaks of the I27 domain. We often got FX traces with forces higher than 200 pN and without a clear I27 fingerprint, which indicated aggregation (see supplemental Fig. S3). The aggregation of CSPFL might be due to the hydrophobic regions at the N and C termini (Fig. 1). We have also made CSP constructs with N-terminal deletion (residues 91–397) and C-terminal deletion (residues 1–290) sandwiched with (I27)3 units for pulling experiments, but the proteins were insoluble, and hence could not be used for the SMFS study.

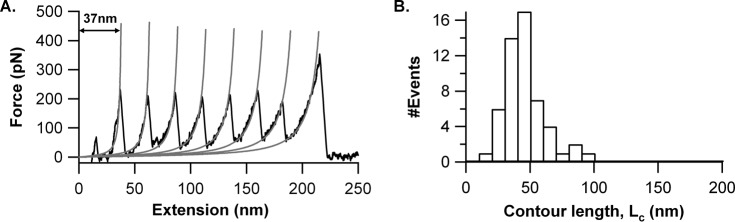

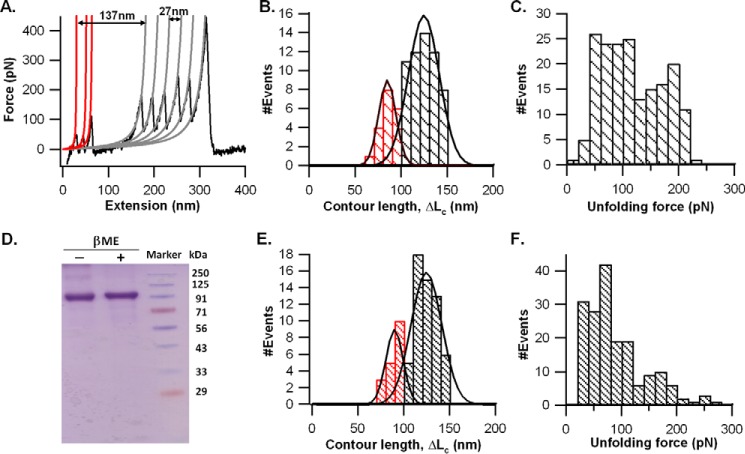

The data from polyprotein (I27)3-CSPΔHP-(I27)3 in reducing and oxidizing conditions is shown in Fig. 5. For CSPΔHP in reducing conditions (buffer containing 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol), we often observed multiple force peaks preceding the I27 sawtooth pattern in FX traces (Fig. 5A). Of the 75 recorded FX traces, there are 12 traces with one force peak, 30 traces with two force peaks, 24 traces with three force peaks, and 9 traces with four force peaks of CSPΔHP. The corresponding histograms of the ΔLc of the first force peak with respect to the first I27 force peak is shown in Fig. 5B. We observed a bimodal distribution for ΔLc, with maxima at ∼89 nm (25%) and ∼128 nm (75%). The CSPΔHP protein consists of CSP, excluding the terminal hydrophobic sequences (i.e. 369 amino acids as shown in Fig. 1). If we assume that the entire protein is folded and the termini are closer, we would expect a contour length of about ∼140 nm as per calculation (369 aa × 0.38 nm/aa). It is possible that the 89-nm contour length reflects a partially unfolded protein, whereas the 128-nm contour length suggests that these protein molecules had to be opened up from a relatively compact folded state. Also, the observed contour lengths of CSPΔHP are much longer than those observed for CSPrep. The multiple force peaks observed for CSPΔHP suggest that the mechanical resistance might come from regions other than NANP repeats (i.e. N-terminal domain, C-terminal domain, or TSR domain). The structure of the TSR domain is known, and it is expected to give ∼22 nm of ΔLc upon unraveling (29, 30). As shown in Fig. 5, the first two CSPΔHP force peaks have ΔLc values in this range, and it is likely that one of these force peaks is due to the TSR domain unraveling. It must be noted, however, that we cannot separate TSR domain unfolding events from others in the FX traces. We have also performed experiments in oxidizing conditions (i.e. without the reducing agent in the buffer) to see whether the disulfide bonds of the TSR domain have any effect on the mechanical properties (Fig. 1A) (29, 30). The mobility of the CSPΔHP polyprotein is similar in reducing and oxidizing conditions as seen on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5D), consistent with the earlier studies (41). The SMFS experiments on the CSPΔHP polyprotein in oxidizing conditions showed that irrespective of the reducing condition, the two populations of proteins with two sets of contour lengths remain virtually unchanged and demonstrate no significant changes in their mechanical properties (Fig. 5E). Interestingly, although the forces required for stretching the proteins remain broadly the same, we observe that the oxidized disulfide-bonded CSPΔHP polyprotein can be unfolded with greater ease (Fig. 5F).

FIGURE 5.

Mechanical unfolding of (I27)3-CSPΔHP-(I27)3 in SMFS experiments. A, FX trace of the CSPΔHP chimera in reducing conditions (5 mm β-mercaptoethanol (βME)) obtained at a pulling speed of 1000 nm/s. The force peaks in the FX trace were fitted to the WLC model. The sawtooth pattern of force peaks with ΔLc ∼27 nm and unfolding force ∼200 pN correspond to the unfolding of I27 (WLC fits are shown in gray), whereas the multiple peaks preceding the I27 sawtooth pattern correspond to the unfolding of CSPΔHP (WLC fits are shown in red). Corresponding ΔLc and unfolding force data are shown in B and C. B, ΔLc between the first force peak of CSPΔHP and the first I27 force peak is found to be a bimodal distribution with Gaussians at 89 ± 8 nm (average ± S.D.), n = 19, and 128 ± 10 nm (average ± S.D.), n = 56. C, distribution of the unfolding forces of all the force peaks of CSPΔHP. The measured unfolding force is 116 ± 54 pN (average ± S.D.), n = 180 (see “Results” for details). D, Coomassie Brilliant Blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel of the (I27)3-CSPΔHP-(I27)3 proteins with and without the reducing agent βME (lanes 1 and 2) showed no significant difference in their mobility. The ΔLc and unfolding force data of the protein in oxidizing conditions (i.e. without βME) are shown in E and F. E, ΔLc between the first force peak of CSPΔHP and the first I27 force peak is found to be a bimodal distribution with Gaussians at 90 ± 8 nm (average ± S.D.), n = 18, and 125 ± 10 nm (average ± S.D.), n = 57. F, distribution of the unfolding forces of all force peaks of CSPΔHP. The measured unfolding force is 88 ± 52 pN (average ± S.D.), n = 177 (see “Results” for details).

Furthermore, it is known that CSP may undergo reversible conformational changes between adhesive (collapsed) and non-adhesive (open) conformations during the sporozoite's journey from mosquito midgut to mammalian liver (18, 32). In the collapsed conformation, it was proposed that there could be an intermolecular interaction between the N-terminal and C-terminal domains of CSP, which needs to be broken to change its conformation to the open state to interact with and invade hepatocytes (32). It was speculated that the conformational change might be due to a mechanical signal. Our experimental results are consistent with these two proposed populations. Based on our observation of a bimodal distribution for ΔLc of CSPΔHP, we can say that the protein might be in both collapsed and open conformations where the collapsed conformation would require a rupture force and gives a long ΔLc, whereas the open conformation is already elongated (i.e. the end-to-end distance of the conformation is large) and gives a short ΔLc upon stretching. Our studies showed that about 75% of the proteins are present in the less unfolded state, whereas 25% of the proteins possess the straight structure. This distribution of the population is independent of the reducing agent, confirming that the covalent disulfide bonds in the TSR domains are unlikely to play a role in the unfolding of the molecules observed under our pulling experiments (Fig. 5), which explore largely the non-covalent interactions Overall, our single-molecule measurements give direct evidence for the existence of two populations, possibly the open and collapsed conformations of CSP.

Discussion

What Is the CSPrep Conformation?

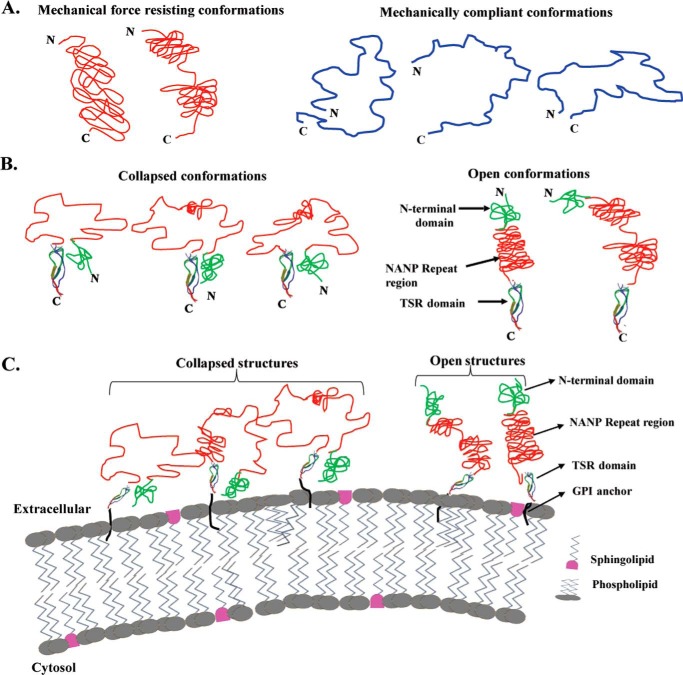

Our SMFS experimental data suggest that CSPrep is conformationally heterogeneous: some of the NANP repeats in a given protein are mechanically resistant, whereas the other repeats are mechanically compliant. The conformations that give observable force peaks might have short stretches of NANP repeats in the resisting structures (Fig. 6A). X-ray structure of NANP and NMR structure of (NANP)3 suggested a super-helical structure for the NANP repeats (28, 42). It is possible that the super-helical structure, as suggested by previous NMR and X-ray data, might resist stretching forces before unraveling. So does the super-helical structure persist over all the NANP repeats? It seems that this is not the case; otherwise, all the CSPrep molecules would have a definite well defined unique conformation, and all the FX traces would have looked similar. On the other hand, the conformations that do not possess long range persistent structure would not give any observable force peak within the instrumental resolution, and they could be unraveled at low forces (<10 pN) (Fig. 6A). Also, the stabilizing force in the NANP super-helical structures is not the strong H-bonding as in the case of β-sheets and other helices in protein structures (31, 42). As proline is a cyclic amino acid, it does not participate in the H-bonding to stabilize helical structures. Hence, the helicity of the NANP repeats does not persist (or extend) for longer lengths within the 43 repeats of CSPrep but lasts only over a few repeats, as observed in the NMR and X-ray studies. However, whenever the super-helical structure is formed, it might require force to unravel it, as observed in our experiments.

FIGURE 6.

Structural model of CSP on the P. falciparum sporozoite surface. A, diagrams showing the potential conformations of CSPrep. Left, the conformations that give observable force peaks might have short stretches of NANP repeats in the resisting structure. Right, conformations that do not give any discernible force peaks in SMFS experiments as they do not have structures that can resist stretching forces. However, there might be a wide distribution of end-to-end lengths giving rise to a wide variation in spacers preceding the unfolding of force marker in chimeric polyproteins, N, N terminus; C, C terminus. B, diagrams showing the potential conformations of CSPΔHP. Left, collapsed conformations where the repeat region acts as a loop. Right, open conformations where the repeat region acts as an elongated rod-like structure. C-terminal TSR domain structure is taken from PDB code: 1VEX. C, schematic representation of CSP conformations anchored on the membrane of sporozoites.

Interestingly, there are other proline-rich regions in proteins such as the PEVK region of giant muscle protein titin, where the proline content is 25%, just as in NANP (34, 35). PEVK regions are not known to have any structure and provide muscle-passive elasticity, and they do not possess any mechanical resistance and unravel at very low forces (34, 35). The fingerprint of PEVK regions is akin to the 40% of FX traces of CSPrep in our study, where they unraveled at very low forces. This further supports our observation of the heterogeneity of conformations in CSPrep. Unlike PEVK, where the entire region is devoid of structure and is mechanically compliant, CSPrep has a mixture of super-helical structure and unstructured regions distributed over the repeat region. The CSP repeats are unique in nature because they all contain prolines at regular intervals in different Plasmodium species and strains (supplemental Table S1). Proline-rich sequences are also known as helix and β-sheet breakers, and overall they provide conformationally rigid structure to protein, i.e. polyproline II (PPII) structure (43–45). However, the structural properties of these repeat sequences in proteins have not been studied in detail as they are difficult to crystallize.

Role of Mechanical Flexibility of CSPrep in Sporozoite Motility

The conformational heterogeneity and the sparsely populated super-helical structure along the CSPrep might have important roles in the motility of the sporozoite. It has been known that CSP covers sporozoite's surface densely and that it is essential for sporozoite's assembly (16). As the sporozoite navigates through the mechanically rigid environment of salivary glands in the mosquito, and through endothelial cells of host vasculature, Kupffer cells, and hepatocytes in the host liver, the densely populated CSP molecules on the sporozoite surface might respond through the mechanical response of CSPrep. When the parasite encounters a rigid/stiff environment during its navigation, the local forces experienced by the CSP molecules due to the parasite squeezing through the harsh environment would stretch the CSPrep and hence may release the “local mechanical stress” by unraveling the super-helical structures and attain their conformations quickly when the stress (or local stretching force) on the molecules is released. Overall, our studies at the single-molecule level suggest that the flexible structure of the NANP repeats may play a key role to sustain the mechanical stress/forces experienced by the densely populated CSP on the sporozoite surface during the navigation of sporozoites.

Role of Mechanical Forces in Conformational Changes of CSPΔHP

The conformational heterogeneity of CSPΔHP might be important in regulating the access to the N-terminal Region I domain or C-terminal TSR domain at different stages of the sporozoite's journey from mosquito's midgut to the mammalian liver (18, 32). Such a reversible conformational change, from a collapsed to open state, is thought to mask some epitopes in the N- and C-terminal domains until the sporozoite interacts with the appropriate host/vector tissues (32). Our results showing the heterogeneity of NANP repeats suggest that they might also contribute to the regulation of the collapsed and open conformations of CSP (Fig. 6B). Also, the interdomain or intermolecular interactions between N-terminal and C-terminal domains may stabilize their conformations (32). The disulfide-containing TSR domain in CSP has been reported to be strikingly divergent in sequence and structure from other TSR domains, including those in other Plasmodium surface proteins (30). The thin and elongated prototypical TSR domain was found to be shortened on its long axis and widened on the other axis, as the N terminus of the CSP TSR domain was located on the same end of the domain as the C terminus, overall constituting a well formed compact structure that did not bind to heparin (30). Our results indicate that under oxidized conditions, where the TSR domain would be well folded, the overall CSP gets to be more unstructured and easier to unfold. Because the TSR domain sequence is extremely conserved in all Plasmodium species, it would appear that the consequent enhanced flexibility of the CSP under non-reducing conditions might be a widespread property of CSP across all species. How the TSR is oriented on the P. falciparum sporozoite surface, between the NANP repeats and C-terminal GPI anchor, remains to be resolved. Our studies show that the conformations of CSP are flexible, and they suggest that weak stretching mechanical forces could be used to change from collapsed to open conformation of CSP on the sporozoite surface (Fig. 6C).

For motility as well as invasion, the sporozoites require a large degree of flexibility. Because CSP constitutes a large fraction of the sporozoite membrane proteins, and because our molecular data suggest the requirement of very low forces in stretching the CSPrep, we speculate that CSP could provide the lubrication to the sporozoites during motility and cell invasion. During this navigation, if the force is high enough locally, then the individual CSP molecules might even be dislodged or pulled out of the membrane as shown by previous studies of shedding CSP from the sporozoite during its movement in liver tissue (24). This would only change the CSP concentration minimally on the parasite surface as the CSP protein is densely populated. It is known from previous studies that newly synthesized CSP is added or replenished from the apical end of sporozoite and that the shedding occurs at the distal end during its motility (24, 46).

In conclusion, our single-molecule force spectroscopy studies on the NANP repeats and near full-length CSP of P. falciparum indicate the heterogeneity of conformations, where some molecules are entirely mechanically compliant, whereas others have both mechanically compliant and mechanically resistant conformations. In the larger propensity of collapsed structures of CSP, the flexible repeat regions would be exposed on the surface and would thus be available for generating the immunodominant antibody response. These mechanical properties of CSP repeats combined with their high density on the sporozoite surface might provide the lubrication required for its navigation through host tissues, whereas the open conformation of CSP molecules would be able to facilitate tissue invasion through interactions with the host receptors.

Experimental Procedures

P. falciparum 3D7 Culture

The maintenance of Plasmodium parasite culture has been described earlier (47). Human blood with O+ blood group was collected in acid citrate dextrose, which is an anticoagulant. The leukocytes were removed, and the erythrocytes were washed and suspended in complete RPMI (complete RPMI with 0.5% AlbuMAX). Asexual stages of P. falciparum 3D7 strain were maintained by adding 5% hematocrit in complete RPMI at 37 °C in a humidified chamber containing 5% CO2.

P. falciparum Genomic DNA Extraction

From the P. falciparum cultures, infected RBCs with ∼10% parasitemia were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 2–5 min at 4 °C. The pellet was washed twice with 1× PBS, and 25 μl of 5% saponin were added followed by centrifugation at 6000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, the lysis buffer was added and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. The DNA was extracted and precipitated by the phenol-chloroform method and sodium acetate-ethanol, respectively. The concentration of the genomic DNA obtained was estimated by absorbance.

Polyprotein Engineering and Cloning and Overexpression of Recombinant CSPs

The gene sequences for CSPFL, CSPrep, CSPΔHP, CSP N-terminal deletion (CSPΔN), and CSP C-terminal deletion (CSPΔC) were amplified using gene-specific primers from purified genomic DNA of P. falciparum and subcloned between the NheI and SacI restriction enzyme sites of the pQE80L vector carrying the I27 heptamer coding gene (37, 38). The resulting plasmid coding (I27)3-CSP(FL or rep or ΔHP or ΔN or ΔC)-(I27)3 was transformed into the BLR(DE3) strain of bacterial cells. The cell culture growth was monitored using A600, and protein expression was induced with 1 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside when A600 reached 0.5–0.8. The induction was kept for 8 h at 37 °C. The cells were then lysed in the lysis buffer (1× PBS, 0.2% (v/v) lysozyme, 5% (v/v) Triton X-100), protease inhibitor was added, and further lysis was carried out by sonication. The protein was purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography as described elsewhere (37, 38). The proteins were eluted from the Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity chromatography in the presence of the reducing agent (5 mm β-mercaptoethanol). After elution, the purified proteins were subjected to slow dialysis, by the addition of buffer without reducing agent for 5–8 h at 4 °C, which should allow the protein to refold back and form the disulfide bonds. After dialysis, further purification was carried out using Superdex-200 (GE Healthcare) on a Bio-Rad BioLogic DuoFlow FPLC system. I27 heptamer protein was also purified using the above mentioned procedure.

SMFS Experiments

Single-molecule pulling experiments were performed on a custom-built atomic force microscope (48). We used a top-view optical head with quadrant photodiode for multimode SPM (TVOH-MMAFM) from Veeco Asia Pte. Ltd., Singapore. We replaced the laser in the optical head with a laser diode (51nanoFCM) coupled to a single mode fiber cable attached to a collimator (60FC-4-M20-10) and micro-focusing system (5M-M25-13-S) from Schäfter + Kirchhoff GmbH, Hamburg, Germany. This atomic force microscopy head was mounted on top of a multi-axis piezoelectric positioning and scanning system with capacitive sensors from Physik Instrumente GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany (PicoCube P-363.3.CD) that allows subnanometer resolution. A custom-made electronics module was used to communicate between the quadrupole diode, the piezoelectric controller, and the data acquisition boards on a personal computer. Data acquisition command modules and further data analysis routines were written using IGOR Pro software from WaveMetrics (Portland, OR). We used the V-shaped, gold-coated reflective silicon-nitride cantilevers from Bruker (Billerica, MA) for pulling experiments. The spring constant of the cantilevers was ∼40 pN/nm as determined using the equipartition theorem (49). All the experiments were performed at room temperature at a constant pulling speed of 1000 nm/s. The concentration of the polyproteins used in the experiment varied between 2 and 10 μm. For pulling studies, 50–70 μl of protein solution in phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) with 5 mm β-mercaptoethanol were added onto the gold-coated coverslip and then left for 10 min before starting pulling experiments. The pulling experiments in oxidizing conditions were performed without any reducing agent in the buffer. The proteins were non-specifically adsorbed onto the coverslip. The proteins were adsorbed onto the cantilever tip by pushing the tip onto the coverslip with a force of 1–2 nN for 0.1–1 s. On retraction, the proteins were stretched if they adsorbed onto the coverslip as well as the tip surface. The single molecules were identified by the number of I27 domains (i.e. between 1 and 6) unfolding in the sawtooth pattern with their characteristic unfolding contour length (∼27 nm) and unfolding forces (∼200 pN) in the FX traces. Only those FX traces containing at least four I27 force peaks were considered for data analysis as this guarantees the stretching of CSP sandwiched by (I27)3 on both sides.

Data Analysis

The following equation of the WLC model of polymer elasticity was used to fit the FX traces (39)

| (Eq. 1) |

where F, p, L, kB, and T denote force, persistence length, contour length, Boltzmann constant, and absolute temperature, respectively.

Author Contributions

S. R. K. A. and S. S. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. A. P. P. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) and Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and supplemental Table S1.

- CSP

- circumsporozoite protein

- TSR

- thrombospondin type 1 repeat

- GPI

- glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- SMFS

- single-molecule force spectroscopy

- N

- newtons

- FX

- force-versus-extension

- WLC

- worm-like chain

- βME

- β-mercaptoethanol

- aa

- amino acids.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (2015) World Malaria Report 2015, WHO Publications, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moorthy V. S., and Ballou W. R. (2009) Immunological mechanisms underlying protection mediated by RTS,S: a review of the available data. Malar. J. 8, 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cohen J., Nussenzweig V., Nussenzweig R., Vekemans J., and Leach A. (2010) From the circumsporozoite protein to the RTS, S/AS candidate vaccine. Hum. Vaccin. 6, 90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. RTS,S Clinical Trials Partnership (2014) Efficacy and safety of the RTS,S/AS01 malaria vaccine during 18 months after vaccination: a phase 3 randomized, controlled trial in children and young infants at 11 African sites. PLoS Med. 11, e1001685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaslow D. C., and Biernaux S. (2015) RTS,S: toward a first landmark on the Malaria Vaccine Technology Roadmap. Vaccine 33, 7425–7432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar K. A., Sano G., Boscardin S., Nussenzweig R. S., Nussenzweig M. C., Zavala F., and Nussenzweig V. (2006) The circumsporozoite protein is an immunodominant protective antigen in irradiated sporozoites. Nature 444, 937–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ellis J., Ozaki L. S., Gwadz R. W., Cochrane A. H., Nussenzweig V., Nussenzweig R. S., and Godson G. N. (1983) Cloning and expression in E. coli of the malarial sporozoite surface antigen gene from Plasmodium knowlesi. Nature 302, 536–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nardin E. H., and Nussenzweig R. S. (1993) T cell responses to pre-erythrocytic stages of malaria: role in protection and vaccine development against pre-erythrocytic stages. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 11, 687–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharma S., Gwadz R. W., Schlesinger D. H., and Godson G. N. (1986) Immunogenicity of the repetitive and nonrepetitive peptide regions of the divergent CS protein of Plasmodium knowlesi. J. Immunol. 137, 357–361 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sharma S., Svec P., Mitchell G. H., and Godson G. N. (1985) Diversity of circumsporozoite antigen genes from two strains of the malarial parasite Plasmodium knowlesi. Science 229, 779–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Enea V., Arnot D., Schmidt E. C., Cochrane A., Gwadz R., and Nussenzweig R. S. (1984) Circumsporozoite gene of Plasmodium cynomolgi (Gombak): cDNA cloning and expression of the repetitive circumsporozoite epitope. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 7520–7524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Galinski M. R., Arnot D. E., Cochrane A. H., Barnwell J. W., Nussenzweig R. S., and Enea V. (1987) The circumsporozoite gene of the Plasmodium cynomolgi complex. Cell 48, 311–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arnot D. E., Barnwell J. W., Tam J. P., Nussenzweig V., Nussenzweig R. S., and Enea V. (1985) Circumsporozoite protein of Plasmodium vivax: gene cloning and characterization of the immunodominant epitope. Science 230, 815–818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nardin E. H., Nussenzweig V., Nussenzweig R. S., Collins W. E., Harinasuta K. T., Tapchaisri P., and Chomcharn Y. (1982) Circumsporozoite proteins of human malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax. J. Exp. Med. 156, 20–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lockyer M. J., and Schwarz R. T. (1987) Strain variation in the circumsporozoite protein gene of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 22, 101–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ménard R., Sultan A. A., Cortes C., Altszuler R., van Dijk M. R., Janse C. J., Waters A. P., Nussenzweig R. S., and Nussenzweig V. (1997) Circumsporozoite protein is required for development of malaria sporozoites in mosquitoes. Nature 385, 336–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferguson D. J. P., Balaban A. E., Patzewitz E.-M., Wall R. J., Hopp C. S., Poulin B., Mohmmed A., Malhotra P., Coppi A., Sinnis P., and Tewari R. (2014) The repeat region of the circumsporozoite protein is critical for sporozoite formation and maturation in Plasmodium. PLoS One 9, e113923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Coppi A., Natarajan R., Pradel G., Bennett B. L., James E. R., Roggero M. A., Corradin G., Persson C., Tewari R., and Sinnis P. (2011) The malaria circumsporozoite protein has two functional domains, each with distinct roles as sporozoites journey from mosquito to mammalian host. J. Exp. Med. 208, 341–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tewari R., Spaccapelo R., Bistoni F., Holder A. A., and Crisanti A. (2002) Function of region I and II adhesive motifs of Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein in sporozoite motility and infectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 47613–47618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Robson K. J., Frevert U., Reckmann I., Cowan G., Beier J., Scragg I. G., Takehara K., Bishop D. H., Pradel G., and Sinden R. (1995) Thrombospondin-related adhesive protein (TRAP) of Plasmodium falciparum: expression during sporozoite ontogeny and binding to human hepatocytes. EMBO J. 14, 3883–3894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Müller H. M., Reckmann I., Hollingdale M. R., Bujard H., Robson K. J., and Crisanti A. (1993) Thrombospondin related anonymous protein (TRAP) of Plasmodium falciparum binds specifically to sulfated glycoconjugates and to HepG2 hepatoma cells suggesting a role for this molecule in sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes. EMBO J. 12, 2881–2889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mishra S., Nussenzweig R. S., and Nussenzweig V. (2012) Antibodies to Plasmodium circumsporozoite protein (CSP) inhibit sporozoite's cell traversal activity. J. Immunol. Methods 377, 47–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mota M. M., Pradel G., Vanderberg J. P., Hafalla J. C., Frevert U., Nussenzweig R. S., Nussenzweig V., and Rodríguez A. (2001) Migration of Plasmodium sporozoites through cells before infection. Science 291, 141–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frevert U., Engelmann S., Zougbédé S., Stange J., Ng B., Matuschewski K., Liebes L., and Yee H. (2005) Intravital observation of Plasmodium berghei sporozoite infection of the liver. PLoS Biol. 3, e192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sinnis P., and Coppi A. (2007) A long and winding road: the Plasmodium sporozoite's journey in the mammalian host. Parasitol. Int. 56, 171–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schofield L., and Uadia P. (1990) Lack of Ir gene control in the immune response to malaria. I. A thymus-independent antibody response to the repetitive surface protein of sporozoites. J. Immunol. 144, 2781–2788 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Topchiy E., Armstrong G. S., Boswell K. I., Buchner G. S., Kubelka J., and Lehmann T. E. (2013) T1BT* structural study of an anti-plasmodial peptide through NMR and molecular dynamics. Malar. J. 12, 104–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bisang C., Weber C., Inglis J., Schiffer C. A., van Gunsteren W. F., Jelesarov I., Bosshard H. R., and Robinson J. A. (1995) Stabilization of type-I β-turn conformations in peptides containing the NPNA-repeat motif of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein by substituting proline for (S)-α-methylproline. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 7904–7915 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tossavainen H., Pihlajamaa T., Huttunen T. K., Raulo E., Rauvala H., Permi P., and Kilpeläinen I. (2006) The layered fold of the TSR domain of P. falciparum TRAP contains a heparin binding site. Protein Sci. 15, 1760–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Doud M. B., Koksal A. C., Mi L.-Z., Song G., Lu C., and Springer T. A. (2012) Unexpected fold in the circumsporozoite protein target of malaria vaccines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 7817–7822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Plassmeyer M. L., Reiter K., Shimp R. L. Jr, Kotova S., Smith P. D., Hurt D. E., House B., Zou X., Zhang Y., Hickman M., Uchime O., Herrera R., Nguyen V., Glen J., et al. (2009) Structure of the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein, a leading malaria vaccine candidate. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26951–26963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Herrera R., Anderson C., Kumar K., Molina-Cruz A., Nguyen V., Burkhardt M., Reiter K., Shimp R. Jr, Howard R. F., Srinivasan P., Nold M. J., Ragheb D., Shi L., DeCotiis M., Aebig J., et al. (2015) Reversible conformational change in the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein masks its adhesion domains. Infect. Immun. 83, 3771–3780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ainavarapu S. R. K., Li L., Badilla C. L., and Fernandez J. M. (2005) Ligand binding modulates the mechanical stability of dihydrofolate reductase. Biophys J. 89, 3337–3344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li H., Oberhauser A. F., Redick S. D., Carrion-Vazquez M., Erickson H. P., and Fernandez J. M. (2001) Multiple conformations of PEVK proteins detected by single-molecule techniques. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10682–10686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sarkar A., Caamano S., and Fernandez J. M. (2005) The elasticity of individual titin PEVK exons measured by single molecule atomic force microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6261–6264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carrion-Vazquez M., Oberhauser A. F., Fowler S. B., Marszalek P. E., Broedel S. E., Clarke J., and Fernandez J. M. (1999) Mechanical and chemical unfolding of a single protein: a comparison. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3694–3699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kotamarthi H. C., Sharma R., Narayan S., Ray S., and Ainavarapu S. R. K. (2013) Multiple unfolding pathways of leucine binding protein (LBP) probed by single-molecule force spectroscopy (SMFS). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14768–14774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kotamarthi H. C., Narayan S., and Ainavarapu S. R. K. (2014) Mechanical unfolding of ribose binding protein and its comparison with other periplasmic binding proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 11449–11454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bustamante C., Marko J. F., Siggia E. D., and Smith S. (1994) Entropic elasticity of λ-phage DNA. Science 265, 1599–1600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ainavarapu S. R. K., Brujic J., Huang H. H., Wiita A. P., Lu H., Li L., Walther K. A., Carrion-Vazquez M., Li H., and Fernandez J. M. (2007) Contour length and refolding rate of a small protein controlled by engineered disulfide bonds. Biophys J. 92, 225–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rathore D., and McCutchan T. F. (2000) Role of cysteines in Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein: interactions with heparin can rejuvenate inactive protein mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8530–8535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ghasparian A., Moehle K., Linden A., and Robinson J. A. (2006) Crystal structure of an NPNA-repeat motif from the circumsporozoite protein of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Chem Commun. (Camb.) 2, 174–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Williamson M. P. (1994) The structure and function of proline-rich regions in proteins. Biochem. J. 297, 249–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bella J., Brodsky B., and Berman H. M. (1995) Hydration structure of a collagen peptide. Structure 3, 893–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Adzhubei A. A., Sternberg M. J., and Makarov A. A. (2013) Polyproline-II helix in proteins: structure and function. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 2100–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vanderberg J. P., and Frevert U. (2004) Intravital microscopy demonstrating antibody-mediated immobilisation of Plasmodium berghei sporozoites injected into skin by mosquitoes. Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 991–996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Das S., Basu H., Korde R., Tewari R., and Sharma S. (2012) Arrest of nuclear division in Plasmodium through blockage of erythrocyte surface exposed ribosomal protein P2. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Aggarwal V., Kulothungan S. R., Balamurali M. M., Saranya S. R., Varadarajan R., and Ainavarapu S. R. K. (2011) Ligand-modulated parallel mechanical unfolding pathways of maltose-binding proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 28056–28065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Florin E. L., Rief M., Lehmann H., Ludwig M., Dornmair C., Moy V. T., and Gaub H. E. (1995) Sensing specific molecular interactions with the atomic force microscope. Biosens. Bioelectron. 10, 895–901 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.