Abstract

ADP-ribosylation factor GTPases are activated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors including Gbf1 (Golgi brefeldin A-resistant factor 1) and play important roles in regulating organelle structure and cargo-selective vesicle trafficking. However, the developmental role of Gbf1 in vertebrates remains elusive. In this study, we report the zebrafish mutant line tsu3994 that arises from N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-mediated mutagenesis and is characterized by prominent intracerebral and trunk hemorrhage. The mutant embryos develop hemorrhage accompanied by fewer pigments and shorter caudal fin at day 2 of development. The hemorrhage phenotype is caused by vascular breakage in a cell autonomous fashion. Positional cloning identifies a T → G nucleotide substitution in the 23rd exon of the gbf1 locus, resulting in a leucine → arginine substitution (L1246R) in the HDS2 domain. The mutant phenotype is mimicked by gbf1 knockouts and morphants, suggesting a nature of loss of function. Experimental results in mammalian cells show that the mutant form Gbf1(L1246R) is unable to be recruited to the Golgi apparatus and fails to activate Arf1 for recruiting COPI complex. The hemorrhage in tsu3994 mutants can be prevented partially and temporally by treating with the endoplasmic reticulum stress/apoptosis inhibitor tauroursodeoxycholic acid or by knocking down the proapoptotic gene baxb. Therefore, endothelial endoplasmic reticulum stress and subsequent apoptosis induced by gbf1 deficiency may account for the vascular collapse and hemorrhage.

Keywords: embryo, Golgi, protein trafficking (Golgi), vascular, zebrafish

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, secretory and membrane proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates need to transport from one compartment to another compartment in the form of vesicles. Cargoes, including newly synthesized proteins and lipids on the ER, are coated by coatomer complex II proteins and transported to the cis-Golgi apparatus and then to the cell surface or other organelles (1). On the other hand, coat proteins and lipids can be retrieved from the Golgi compartments to the ER via COPI vesicles (2, 3). These transport pathways are essential for development and homeostasis, and their disruption can result in various disease phenotypes (4–6).

The ADP-ribosylation factors (ARFs)2 are guanine nucleotide-binding (G) proteins in eukaryotic cells, which are activated when bound to GTP. ARFs play important roles in regulating organelle structure and cargo-selective vesicle trafficking (7–9). For example, Arf1 in combination with Arf4 at the cis-Golgi and ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) can recruit COPI to form COPI-coated vesicles for transporting cargoes to the ER, and Arf3, Arf4, and Arf5 at the trans-Golgi network can recruit other coat proteins to form carrier vesicles for transporting cargoes (10).

ARF-GDP binds to and is converted by ARF guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) to the active form ARF-GTP. Gbf1 is one of the high molecular weight ARF-GEFs, initially identified as a factor whose overexpression can relieve the inhibitory effect of BFA on the membrane recruitment of ARFs, coatomer proteins, and other trafficking cargoes (11, 12). Gbf1 consists of multiple domains, including the N-terminal DCB domain for dimerization and HUS domain probably for membrane recruitment, the middle sec7 domain essential for the GEF activity and membrane recruitment, and the C-terminal HDS domains (HDS1–HDS3) possibly for intracellular destination (reviewed by Ref. 13). Because of high molecular weight, the exact functions and mechanisms of different domains of Gbf1 are not well determined and remain elusive.

In vitro studies have shed light on important function of mammalian Gbf1. Knockdown of GBF1 in cultured mammalian cells leads to abnormal distribution of ER exit sites, ERGIC and cis-Golgi elements, and COPI complexes, ultimately inhibiting trafficking of transmembrane proteins and inducing unfolded protein response and cell death (14–16). Several studies have demonstrated that GBF1 is necessary for replication and infection of pathogens and viruses (17–20) and thus could serve as an anti-infection target. However, the physiological roles of Gbf1 in vertebrate organisms have yet to be investigated.

In this study, we report an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-induced gbf1 mutant line in zebrafish, representing the first Gbf1-deficient vertebrate model. This line carries a T → G mutation in the 23rd exon of the gbf1 locus, which results in a L1246R substitution in the HDS2 domain of Gbf1 protein. The zygotic gbf1 mutant embryos display intracerebral and trunk hemorrhage after 40 h postfertilization (hpf). The hemorrhage phenotype may result from defective intracellular cargo trafficking systems and thereby endothelial apoptosis.

Results

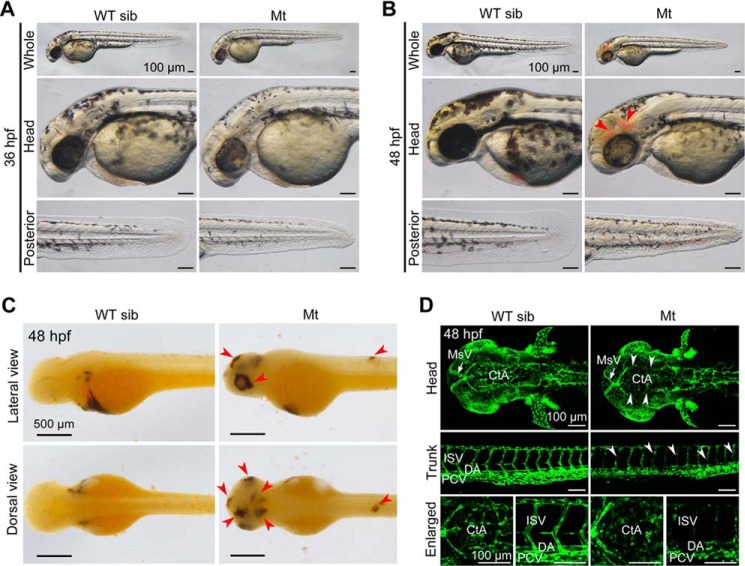

tsu3994 Mutant Embryos Exhibit Hemorrhage in the Head and Trunk

In an ENU-mediated mutagenesis screen, we identified a zygotic mutant line, tsu3994. We observed that 24.75% of embryos (n = 298) from crosses between heterozygotes started to show reduced pigmentation in the head and much shorter caudal fin at 36 hpf (Fig. 1A), which suggests Mendelian inheritance of the phenotype. At 48 hpf, 95% of mutant embryos (n = 137) developed hemorrhage in the head and/or in the trunk region (Fig. 1B). The leaking blood cells were easily seen in the brain, eyes, and trunk after O-dianisidine staining (Fig. 1C). The head tended to have more bleeding sites than the trunk region. All of mutant embryos died before 96 hpf. Our subsequent study focused on the hemorrhage phenotype.

FIGURE 1.

Developmental defects in tsu3994 mutant embryos. A and B, Mt embryos showing reduced pigmentation and shorter caudal fin at 36 hpf (A) and additionally hemorrhage (indicated by arrowheads) at 48 hpf (B). Wild-type siblings (WT sib) from the same batch served as control. C, O-dianisidine staining detected leaking red blood cells in the head, eyes, and trunk (indicated by arrowheads) in mutant embryos at 48 hpf. D, vascular defects in mutants in Tg(fli1a:EGFP) transgenic background at 48 hpf. Some intracerebral vessels (top panels, dorsal views) and intersegmental vessels (middle panels, lateral views) were disappeared or disconnected (indicated by arrowheads). The bottom panels show enlarged parts. MsV, mesencephalic vein; DA, dorsal aorta; PCV, posterior caudal vein.

Because hemorrhage is an indication of leakage or dysfunction of the vascular system, we introduced the tsu3994 mutant allele into the Tg(fli1a:EGFP) transgenic background, in which blood vessels are labeled by EGFP (21), to observe vascular defects. Confocal microscopy revealed that the vasculature system of mutant embryos is normal before 30 hpf (data not shown), indicating that vasculogenesis in mutant embryos is unaffected. However, at 48 hpf, some vessels, primarily intracerebral vessels in the head and intersegmental vessels (ISVs) in the trunk, in mutants are broken or disappeared (Fig. 1D). In particular, central arteries (CtAs) in the head of mutants are almost lost completely, probably because these CtAs form at later stage (36 hpf) than dorsal aorta, posterior cardinal vein, and ISVs (24–30 hpf) (22) and can be affected more easily.

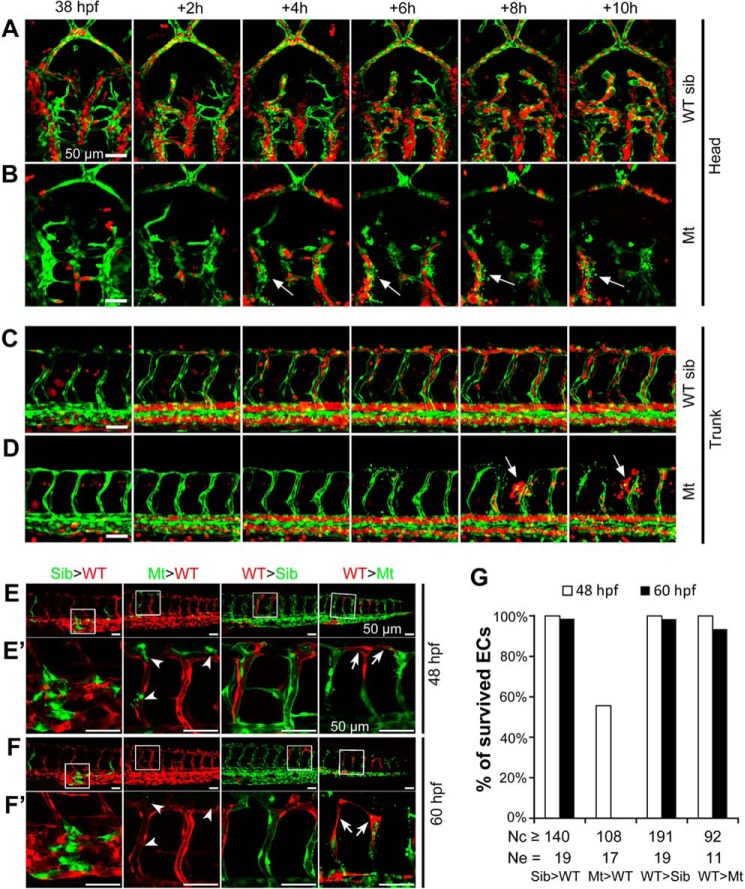

To dynamically observe the vascular defects, we generated tsu3994 mutants in the Tg(kdrl:GFP;gata1a:DsRed) double transgenic background. In WT sibling embryos, gata1a-positive blood cells circulated normally through the vasculature from 38 to 48 hpf (Fig. 2, A and C, and supplemental Movies S1 and S2, left panels); in mutant embryos, however, intracerebral vessels and ISVs collapsed at some sites, resulting in disassociation of endothelial cells (ECs) and flowing away of blood cells (Fig. 2, B and D, and supplemental Movies S1 and S2, right panels). These observations imply that the vasculature integrity and homeostasis might have been disrupted in mutants.

FIGURE 2.

Vascular defects of tsu3994 mutant embryos. A–D, time lapse confocal imaging shows vascular breakage in the intracerebral (B) and intersegmental vessels (D) of mutants. Mt (B and D) and WT sibling (sib, A and C) embryos were generated in Tg(kdrl:GFP;gata1a:DsRed) double transgenic background, in which vasculature and blood cells were labeled by GFP (green) and DsRed (red), respectively. Arrows indicate cracking sites of vessels (B and D). Time points are indicated. See also supplemental Movies S1 and S2. E–G, vascular defect of tsu3994 mutants is cell autonomous. tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) Mt and sibling (Sib) embryos and Tg(kdrl:mCherry) transgenic embryos were used for transplantation at the shield stage in the indicated ways, and host embryos were observed by confocal microscopy at 48 hpf (E and E′) and 60 hpf (F and F′). The boxed areas in E and F are enlarged in E′ and F′, respectively. Arrowheads and arrows in E′ and F′ indicate deforming mutant donor ECs (green) in a WT host embryo and surviving donor WT ECs in a mutant host embryo, respectively. G, the rate of survived ECs. Nc, number of observed ECs; Ne, number of observed embryos.

The Vascular Defect in tsu3994 Is Cell Autonomous

To determine the cellular origin of the vascular defect in tsu3994, we performed cell transplantation between tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) and Tg(kdrl:mCherry) transgenic embryos at the shield stage and observed trunk ECs differentiated from donor cells at 48 and 60 hpf. We found that ECs differentiated from transplanted tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) WT sibling cells in the WT Tg(kdrl:mCherry) hosts or ECs differentiated from WT Tg(kdrl:mCherry) donor cells in the tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) WT sibling hosts had a survival rate of over 98% (Fig. 2, E–G). When WT Tg(kdrl:mCherry) cells were transplanted into tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) mutant host embryos, the donor-derived ECs still showed a survival rate of 100% at 48 hpf and 93.48% at 60 hpf (n = 92), even if the adjacent vessels were broken (Fig. 2, E′ and F′). However, 44% of ECs (n = 108) derived from tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) mutant donors in the WT Tg(kdrl:mCherry) hosts were deforming at 48 hpf, and all of these donor-derived ECs disappeared or deformed at 60 hpf (Fig. 2, E′ and F′). These data indicate that the vascular defect in tsu3994 mutants is cell autonomous.

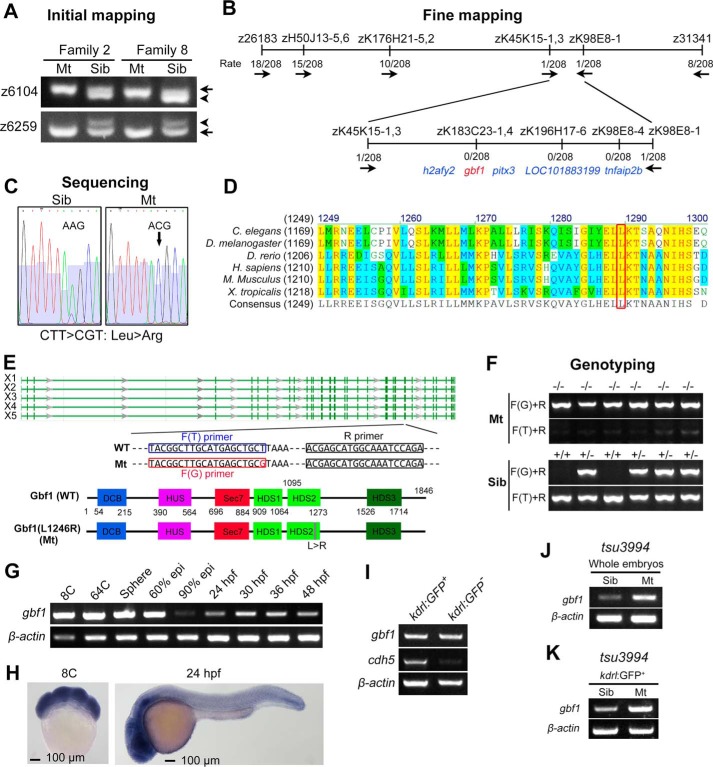

Loss of Function of gbf1 Accounts for tsu3994 Mutant Phenotype

To uncover the responsible genetic modification in tsu3994 mutants, we performed classic positional cloning as published previously by the Zon lab (23). The initial mapping in two families located the mutation site on chromosome 13, with two SSLP markers, z6104 and z6259, showing strong association with the mutant phenotype (Fig. 3A). Through chromosomal walking and fine mapping, the mutation site was further narrowed to a ∼140-kb region, which harbors five candidate genes, i.e. tnfaip2b, LOC101883199, pitx3, gbf1, and h2afy2 (Fig. 3B). Then sequencing coding regions of these genes revealed that gbf1 in mutant embryos carried a T → G single nucleotide substitution in the 23rd exon (Fig. 3C). This T → G mutation is predicted to cause a leucine → arginine substitution (L1246R for X5 isoform of Gbf1) in Gbf1 protein, which is highly conserved across animal species from Caenorhabditis elegans to human (Fig. 3D). According to the NCBI database, zebrafish gbf1 may produce five transcription variants (X1–X5), which all encode an identical protein except for a few amino acids in the non-conserved linker regions. The full-length Gbf1 X5 isoform (WT) consists of 1846 residues and the L1246R mutation resides in the highly conserved HDS2 domain (13, 24) (Fig. 3E). As shown in Fig. 3 (E and F), the WT and mutant alleles could be precisely identified by PCR using a common reverse primer (R primer) in combination with a WT forward primer (F(T) primer) or a mutant-type (F(G)) forward primer.

FIGURE 3.

Genetic mapping of mutant gene in tsu3994 mutants. A, initial mapping positioned the mutation site around the markers z6104 and z6259 on chromosome 13. Arrows and arrowheads indicate the polymorphic bands derived from Tu and India alleles, respectively. B, fine mapping results. The combination rates are shown, and the direction is indicated by arrows. C, a T → G point mutation was detected within the gbf1 coding sequence, presumably leading to Leu → Arg substitution in Gbf1 protein. D, the mutated leucine residue (boxed) of Gbf1 is evolutionally conserved across different species. E, genomic structure and splicing variants (X1–X5) of the zebrafish gbf1 locus and motif composition of Gbf1 protein with positions indicated. The sequences of primers used for genotyping were indicated. F, examples of genotyping results of mutants and siblings. G and H, expression of gbf1 transcripts in WT embryos at indicated stages was examined by RT-PCR (G) and in situ hybridization (H). I, transcription levels of gbf1 and cdh5 in kdrl:GFP+ ECs and in kdrl:GFP− non-ECs sorted from Tg(kdrl:GFP) embryos at 48 hpf were analyzed by RT-PCR. J and K, transcription levels of gbf1 in whole embryos (J) or in ECs sorted from tsu3994:Tg(kdrl:GFP) embryos (K) at 44 hpf were analyzed by RT-PCR.

We investigated the expression pattern of gbf1 by whole mount in situ hybridization and RT-PCR. The results disclosed that gbf1 is maternally and zygotically expressed; its transcripts are ubiquitously distributed at early stages but enriched in the head region at later stages in WT embryos (Fig. 3, G and H). Importantly, gbf1 is also expressed in endothelial cells isolated from Tg(kdrl:GFP) embryos (Fig. 3I), which is consistent with its cell autonomous function in the vasculature. In mutant embryos, the expression level of gbf1 appeared to be higher as a whole (Fig. 3J) or specifically in endothelial cells (Fig. 3K), which may result from unknown compensatory mechanisms.

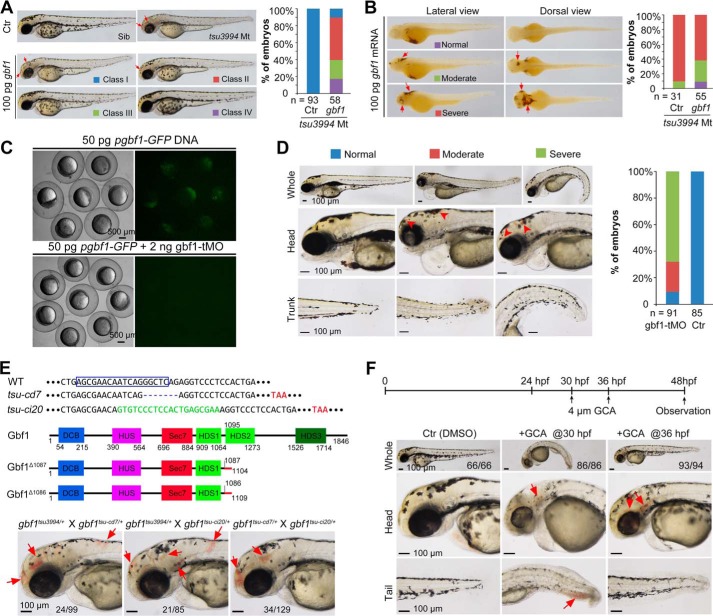

To further validate the implication of the gbf1 T → G mutation, we first performed rescue experiments using gbf1 WT or mutant (T → G) mRNA. Injection of 100 pg of gbf1 WT mRNA at the one-cell stage could partially and temporally ameliorate the mutant phenotypes, including decreased pigments and hemorrhage (Fig. 4, A and B). In contrast, injection of gbf1 mutant mRNA neither caused any phenotype in WT embryos nor rescued the mutant phenotype in mutant embryos (data not shown), which suggests that the mutant Gbf1 is a loss of function form rather than a dominant negative form. Next, we knocked down gbf1 in WT embryos using a translation blocker morpholino (gbf1-tMO) (Fig. 4C). Injection with high doses (>4 ng) impaired early development of embryos (data not shown), likely manifesting a maternal effect of gbf1. At a lower dose (2 ng), morphants developed hemorrhage phenotype mimicking mutant embryos (Fig. 4D). Then we generated new gbf1 mutant lines by targeting the 23th exon using Cas9 technology. Subsequently, we identified gbf1tsu-cd7 and gbf1tsu-ci20 mutations, which carried a 7-bp deletion and a 20-bp insertion, respectively (Fig. 4E). Both mutations caused a frameshift, presumably resulting in a truncated Gbf1 protein lacking the HDS2, HDS3, and C-terminal proline-rich domains. Approximately 25% of embryos derived from gbf1tsu-3994/+ ×gbf1tsu-cd7/+, gbf1tsu3994/+ × gbf1tsu-ci20/+, or gbf1tsu-cd7/+ × gbf1tsu-ci20/+ crosses developed hemorrhage at 48 hpf (Fig. 4E), suggesting that all of these mutant alleles are non-functional. Furthermore, the tsu3994 mutant phenotype could be simulated by treating WT embryos with the Gbf1 inhibitor GCA (25) (Fig. 4F). Taken together, these data strongly support the idea that the tsu3994 mutant phenotype is caused by loss of function of gbf1.

FIGURE 4.

Confirmation of gbf1 mutant phenotypes. A and B, rescue effect of gbf1 overexpression on hypopigmentation (A) and hemorrhage (B) in tsu3994 mutants. Embryos were injected at the one-cell stage with 100 pg gbf1 mRNA, observed at 48 hpf, and individually genotyped by PCR. Representative pictures of different classes and statistical data are shown on the left and right, respectively. n, number of observed embryos. The bleeding sites are indicated by arrows. C, test of effectiveness of gbf1-tMO. Wild-type embryos at the one-cell stage were injected and observed for GFP fluorescence by fluorescent microscopy at the shield stage. D, morphants showed hemorrhage (indicated by arrowheads) at 96 hpf with statistical data on the right. n, number of observed embryos. Note that most of morphants had edema that was not seen in tsu3994 mutants, which might arise from nonspecific effect. E, generation of gbf1 knock-out by Cas9 technology. The top panel showed the DNA sequences. The boxed area shows the gRNA-recognized sequence. −, deleted base; green, inserted bases; red, premature stop codon. The middle panel diagrams structures of WT and predicted mutant proteins. The bottom panel shows similar phenotypes of mutants carrying two different mutant alleles. The ratio of mutants derived from the same cross was indicated. Arrows indicate hemorrhage sites. F, phenotype in embryos treated with the Gbf1 inhibitor GCA. The top panel showed the start time points of treatment. The head and posterior trunk are shown in the middle and bottom panels, respectively, and hemorrhage sites are indicated by arrows. The ratio of embryos with the representative morphology is indicated.

Gbf1(L1246R) Is Inefficiently Recruited to the Golgi Apparatus

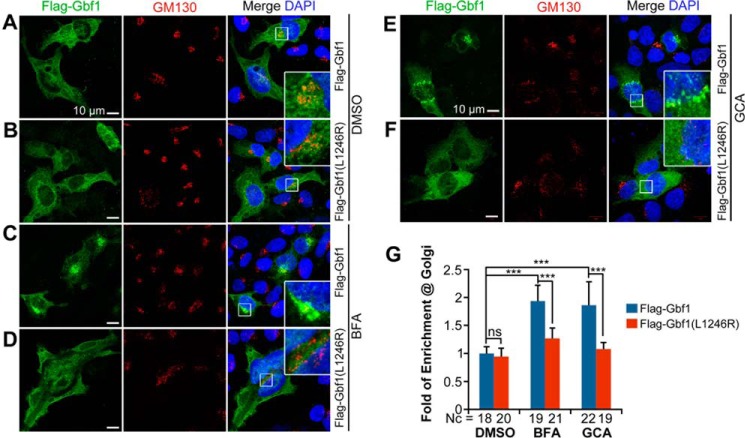

Gbf1 is an ARF GEF, which binds to and promotes the exchange of GDP bound by ARF for GTP. Gbf1 is rapidly dissociated from membrane-anchoring ARF upon the formation of ARF-GTP so that Gbf1 looks ubiquitously distributed in mammalian cells (26–28). The ARF-GDP-GBF1 complex can be stabilized by the Gbf1 inhibitor BFA, allowing enrichment of Gbf1 in the Golgi region (11, 12, 26, 29). We asked whether the L1246R mutation causes subcellular displacement of zebrafish Gbf1. When overexpressed in HeLa cells, both Flag-Gbf1 (WT) and Flag-Gbf1(L1246R) of the zebrafish origin were slightly enriched in the cis-Golgi marked by the cis-Golgi tethering protein GM130 (Fig. 5, A, B, and G). When the cells were treated with BFA or GCA, Flag-Gbf1 was prominently enriched in the cis-Golgi region (Fig. 5, C, E, and G), whereas less Flag-Gbf1(L1246R) was recruited to the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 5, D, F, and G). These results suggest that the Leu → Arg mutation disrupts the Golgi targeting property of Gbf1 protein; in other words, the HDS2 domain is required for localization of Gbf1 to the Golgi apparatus.

FIGURE 5.

Gbf1(L1246R) mutant protein is unable to be recruited to the Golgi apparatus in HeLa cells. A–F, location of expressed Flag-Gbf1 (A, C, and E) and mutant Flag-Gbf1(L1246R) proteins (B, D, and F) in the absence (A and B) or presence (C–F) of BFA (C and D) for 10 min or GCA (E and F) for 30 min. The insets are enlarged boxed areas showing co-localization of exogenous Gbf1 with the cis-Golgi marker GM130. Note that BFA or GCA treatment enriched WT Gbf1 in the Golgi region (C and E) but had little effect on mutant Gbf1 (D and F). More dispersed and weaker GM130 signals in BFA- or GCA-treated cells (C–F) may be caused by partial disruption of the Golgi apparatus because of inhibition of endogenous Gbf1. G, statistical results of relative Gbf1 signal in the Golgi region. Fold of enrichment at Golgi was expressed as the ratio of the Flag-Gbf1 signal co-localized with the GM130-labeled Golgi region to the Flag-Gbf1 signal in the whole cell. Nc, observed number of cells; ns, statistically nonsignificant; ***, p < 0.001.

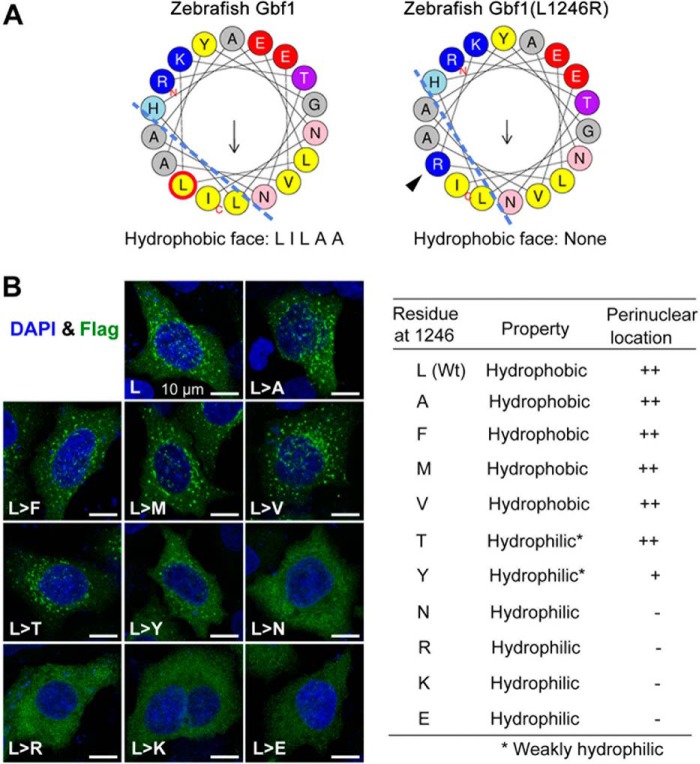

We note that the L1246R substitute resides within the fifth α-helix of the HDS2 domain that is highly conserved in the BIG/GBF family from yeasts to human (Fig. 3D) (24). The α-helix property plotted by HELIQUEST (30) suggests that the L1246R substitution leads to loss of the hydrophobic face (Fig. 6A). We found that replacement of Leu1246 by the strong hydrophilic amino acids Asn, Arg, Lys, and Glu altered Flag-Gbf1 distribution, whereas substitution by other hydrophobic or weaker hydrophilic amino acids had no or little effect (Fig. 6B). Thus, the hydrophobic face of the fifth α-helix in the HDS2 domain is necessary for Gbf1 translocation to the Golgi apparatus, which is possibly involved in protein-protein interaction.

FIGURE 6.

The hydrophobic property of L1246 is required for Gbf1 translocation to the Golgi apparatus. A, illustration of predicted hydrophobic face of the corresponding α-helix. Ley → Arg substitution would disrupt the hydrophobic face (dashed lines). B, Flag-Gbf1 with different residues at the position 1246 showed different locations in HeLa cells. The HeLa cells transfected with different expression constructs were treated for 12 h with 10 μm GCA before harvest for immunostaining with Flag antibody. Representative confocal images are shown on the left. The intracellular location is summarized in the table. The ERGIC/Golgi location was reflected by enriched signals in the perinuclear region.

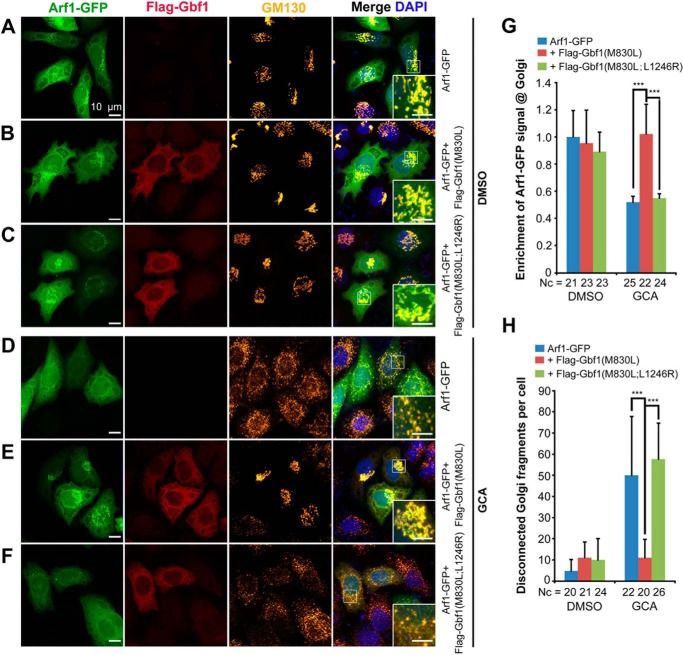

Gbf1(L1246R) Fails to Activate Arf1 for Recruiting COPI Complex

Activation of Arf1 by a guanine exchange factor such as Gbf1 is important for maintaining the ER and Golgi integrity and for recruiting COPI complex (31). We wondered whether Gbf1(L1246R) lacks the activity to activate Arf1. Given that only the active ARF-GTP stably retains in the Golgi apparatus to recruit downstream coat proteins (28), we evaluated the Gbf1 GEF activity by essaying Golgi enrichment of zebrafish Arf1 in HeLa cells. We introduced the M830L mutation into Flag-Gfb1 and Flag-Gfb1(L1246R) to generate Flag-Gfb1(M830L) and Flag-Gfb1(M830L;L1246R), respectively, which should confer insensitiveness to BFA/GCA treatment as does human GBF1(M832L) (26). In the absence of GCA, Arf1-GFP, whenever transfected alone or co-transfected with Flag-Gbf1(M830L) or Flag-Gbf1(M830L;L1246R), were apparently enriched in the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 7, A–C and G). The addition of GCA, which inhibits function of endogenous GBF1 and causes Golgi fragmentation (as indicated by scattering GM130), resulted in decentralized distribution of overexpressed Arf1-GFP (Fig. 7, D and G). However, the accumulation of Arf1-GFP in the Golgi apparatus was achieved in the presence of GCA by overexpressing Flag-Gbf1(M830L) (Fig. 7, E and G) but not Flag-Gbf1(M830L;L1246R) (Fig. 6, F and G). Furthermore, overexpression of Flag-Gbf1(M830L) but not Flag-Gbf1(M830L;L1246R) largely rescued the integrity of the Golgi apparatus disrupted by GCA treatment (Fig. 7, E, F, and H). Therefore, Gbf1(L1246R) most likely lacks the activity to activate Arf1.

FIGURE 7.

Gbf1(L1246R) mutant protein lacks the activity to restore Golgi integrity and Arf1 recruitment in cells lacking endogenous GBF1 activity. A–F, immunofluorescent detection of exogenous tagged fusion proteins and GM130-positive cis-Golgi compartment in HeLa cells in the absence (A–C) or presence (D–F) of GCA for 45 min. The insets are enlarged boxed areas showing location of exogenous Arf1-GFP in the cis-Golgi region. The M830L mutation in Gbf1 confers insensitivity to GCA treatment. Note that GCA treatment caused diffuse distribution of Arf1-GFP throughout the cell and fragmentation of the Golgi apparatus as indicated by disperse distribution of GM130 signal (D), which were ameliorated by expression of Gbf1(M830L) (E) but not Gbf1(M830L;L1246R) (F). G, relative enrichment of Arf1-GFP signal in the Golgi region, which was the ratio of Arf1-GFP signal within the GM130+ Golgi region to the Arf1-GFP signal in the whole cell with background noise deducted. H, quantification of Golgi fragmentation. The number of disconnected Golgi fragments marked by GM130 within a cell was counted. Nc, number of cells; ***, p < 0.001.

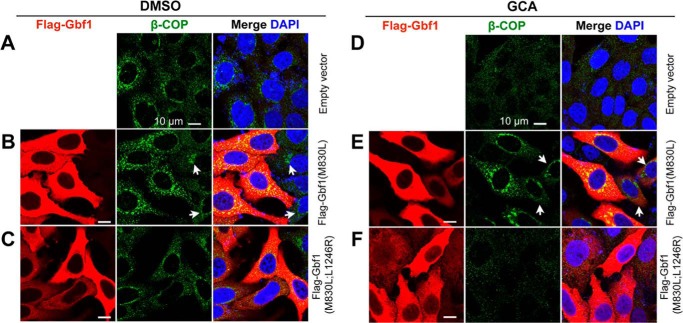

Next, we determined whether Gbf1(L1246R) has the activity to promote ER-Golgi membrane recruitment of the COPI complex by observing location of β-COP, a coatomer protein subunit of the COPI complex. The endogenous β-COP protein was located on the transporting vesicles (large speckles) with enrichment in the perinuclear region (Fig. 8A), which was enhanced by transfection of Flag-Gbf1(M830L) (Fig. 8B) but not by Flag-Gbf1(M830L;L1246R) expression (Fig. 8C). GCA treatment led to disappearance of β-COP-containing speckles (Fig. 8D), and those speckles reappeared following transfection of Flag-Gbf1(M830L) (Fig. 8E) but not Flag-Gbf1(M830L;L1246R) (Fig. 8F). Taken together, the above data indicate that L1246R mutation of zebrafish Gbf1 is unable to activate Arf1, ultimately leading to inefficient recruitment of the trafficking vesicle components.

FIGURE 8.

Gbf1(L1246R) mutant protein fails to recruit β-COP to the Golgi apparatus. Flag-tagged Gbf1(M830L) or Gbf1(M830L;L1246R) was transfected into HeLa cells. The transfected cells were incubated for 24 h, and then DMSO or GCA was added. The cells were harvested for immunodetection of Flag-Gbf1 and endogenous β-COP 12 h post DMSO (A–C) or GCA treatment (D–F). Regardless of GCA, expression of Gbf1(M830L) promoted recruitment of β-COP to the perinuclear Golgi region (B and E), whereas Gbf1(M830L;L1246R) expression had no effect (C and F). Arrows in (B and E) indicated cells with low level Gbf1(M830L) expression and showing less amount of enriched β-COP compared with cells with high-level Gbf1(M830L) expression.

Numerous Genes Are Up-regulated in Endothelial Cells of tsu3994 Mutants

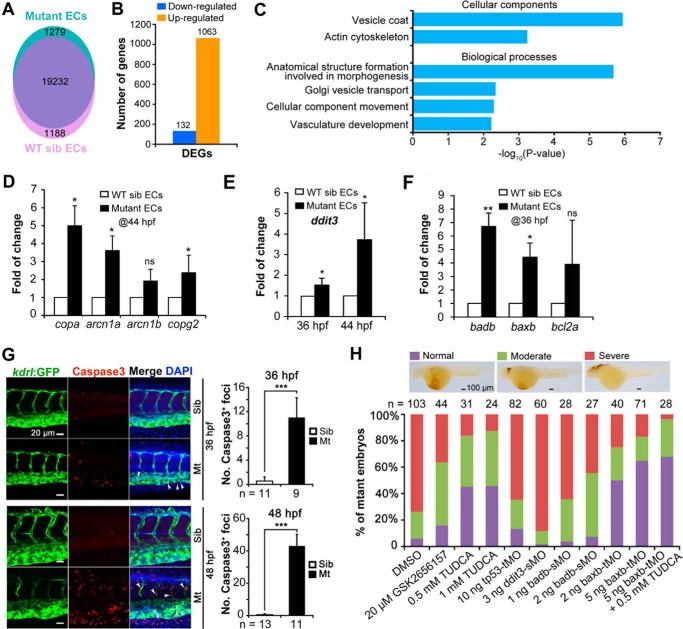

We analyzed, by RNA-Seq, transcriptional profiles of kdrl:GFP+ ECs sorted from tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) mutant or WT sibling embryos at 44 hpf. For each sample, transcripts of more than 20,000 genes were mapped to the zebrafish genome assembly Zv10 (Fig. 9A). Compared with kdrl:GFP+ ECs from WT siblings, ECs from mutants had 1063 up-regulated and 132 down-regulated genes (>2.0-fold with false discovery rate of <0.001) (Fig. 9B). Gene Ontology term analysis disclosed markedly increased expression levels of genes for vesicle transport, in particular for vesicle coatomer proteins (Fig. 9C). Real time RT-PCR analysis confirmed the significant increase of expression levels of copa, arcn1a, and copg2 in mutant kdrl:GFP+ endothelial cells (Fig. 9D). It is likely that impaired vesicle trafficking in mutant endothelial cells evokes unknown compensatory mechanisms to increase the expression levels of vesicle coatomer genes.

FIGURE 9.

Transcription profiles and apoptosis of tsu3994 mutant ECs. A–C, transcription profiling of tsu3994 ECs. kdrl:GFP+ ECs were sorted from tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) mutant or sibling embryos at 44 hpf for RNA-Seq analysis. A, gene numbers mapped to the zebrafish genome assembly version Zv10 in different samples. B, number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the two samples (>2-fold with a false discovery rate of <0.001). C, Gene Ontology term categories with enriched expression for up-regulated genes in mutant ECs. D–F, expression levels of several vesicle coat genes and ER stress/apoptosis-related genes were analyzed at indicated stages by real time quantitative PCR. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ns, statistically nonsignificant. G, tsu3994 embryos have more apoptotic endothelial cells. tsu3994;Tg(kdrl:GFP) Mt and wild-type sibling (Sib) embryos were immunostained for active caspase 3 (red) and GFP (green) at 36 and 48 hpf. A trunk region was shown. The apoptotic endothelial cells in mutants were indicated by arrowheads. Note that mutant embryos also had more apoptotic cells outside the vasculature that are likely to include blood cells leaking from broken vessels and other types of cells. The average number of Caspase 3+ endothelial cells within four intersegmental vessels at comparable regions in Mt and siblings was shown on the right. H, effect of GSK2656157 and TUDCA treatments and knockdown of several apoptotic genes on hemorrhage in tsu3994 mutants. The treated or MO-injected embryos were subjected to O-dianisidine staining at 48 hpf. Following photograph, embryos were individually genotyped, and the mutants were classified into three categories as exemplified on the top. n, number of observed embryos; ***, p < 0.001.

Inhibition of ER Stress and Apoptosis Compromises Hemorrhage in tsu3994 Mutants

Interestingly, we observed a significant increase of the ER stress marker ddit3/chop, as well as the proapoptotic genes badb and baxb in mutant endothelial cells (Fig. 9, E and F). In mammals, Ddit3, Bad, and Bax can promote cell death (32–34). We guessed that tsu3994 mutants might have more apoptotic endothelial cells. Immunofluorescent detection of active Caspase3 indeed identified many more apoptotic endothelial cells in mutants at 36 and 48 hpf (Fig. 9G). Then we tried to inhibit apoptosis to prevent hemorrhage in mutants by suppressing ER stress and knocking down proapoptotic genes. As a result, treatment with the ER stress and apoptosis inhibitor TUDCA (35) and knockdown of baxb were found to prevent bleeding in mutant embryos (Fig. 9H); baxb knockdown in combination with TUDCA treatment showed an even better effect. Knockdown of badb or inhibition of the stress sensor protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) with GSK2656157 could reduce the proportion of mutant embryos with severe hemorrhage, exhibiting certain levels of rescue effect. However, knockdown of ddit3 and tp53 had no effect on hemorrhage occurrence (Fig. 9H). It is likely that impaired vesicle trafficking and cargo transportation caused by deficiency of Gbf1 trigger ER stress and apoptosis in endothelial cells, ultimately leading to vascular breaches. Interestingly, defects in pigmentation and fins in tsu3994 were not obviously compromised by TUDCA treatment or/and baxb knockdown (data not shown), suggesting that molecular mechanisms underlying different defects are distinct.

Discussion

Gbf1 serves as a large ARF-GEF, and in vitro studies have disclosed that Gbf1 is essential for maintaining Golgi structures and thus for vesicle trafficking and protein transportation in mammalian cells (14–16). However, the embryonic function of Gbf1 in vertebrates remains unknown. In this study, we generated the zebrafish gbf1 mutant line, the first Gbf1-deficient vertebrate model. The deficiency of zygotic gbf1 causes hemorrhage, hypopigmenation, and malformation of caudal fin during embryonic development. The hemorrhage arises from the cell autonomous breakage of vascular vessels and can be prevented by inhibition of apoptosis. The phenotype of the zebrafish gbf1 mutant is similar to human autosomal recessive inherited Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, which is characterized by hypopigmentation and bleeding tendency and is ascribed to mutations of genes involved in vesicle trafficking and protein secretion (36, 37). It is worth noting that dozens of documented single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the human GBF1 locus, such as rs11558771, rs144633658, and rs375518420, predictably result in a premature stop codon with no synthesis of functional GBF1 protein. It would be interesting to investigate the clinical features of people who carry this kind of GBF1 mutation.

Zebrafish gbf1 is ubiquitously expressed. The fact that gbf1 zygotic mutants have no detectable defects during early embryogenesis may be attributed to the abundance of maternal Gbf1. Even at later embryonic stages, not all tissues in the gbf1 zygotic mutants showed obvious morphological defects. For example, the ears of gbf1 mutants look morphologically normal. In flies, depletion of garz, the mammalian GBF1 homolog, causes incomplete luminal diameter expansion of epithelial tubes such as salivary glands and trachea (38). We demonstrate that the deficiency of gbf1 in the zebrafish leads to sporadic breaches of vascular vessels that also belong to an epithelial tubular tissue. It is likely that the vasculature is prone to apoptosis and subsequent rupture in response to the ER-Golgi stress induced by defective vesicle trafficking. The other types of tissues may be more capable of tolerating ineffective Gbf1-mediated vesicle trafficking. On the other hand, the zebrafish genome encodes other large ARF-GEFs such as big2/arfgef2 and big3/arfgef3 as well. The unaffected tissues in gbf1 mutants may associate with redundant or compensatory expression of other ARF-GEF genes or stimulation of other unknown pathways.

A previous study has shown that human GBF1 lacking the HDS2 domain is unable to locate to ERGIC and Golgi membranes (39). We show that the single amino acid substitution L1246R within the HDS2 domain of zebrafish Gbf1, arising from chemical mutagenesis, abolishes its Golgi membrane targeting property and causes a complete loss of function. Therefore, the HDS2 domain is essential for Gbf1 function in vertebrate animals. However, the exact molecular mechanisms underlying the activity loss of Gbf1(L1246R) need further investigation.

GBF1 is required for infection of viruses and considered to be a potential target for developing antiviral drug. We should consider the side effects of such drugs on tissue homeostasis given that GBF1 plays an important role in the maintenance of tissue homeostasis.

Experimental Procedures

Zebrafish Strains and Maintenance

Fish or embryos of the Tuebingen (Tu) and India strain were used. The transgenic lines Tg(fli1a:EGFP)y1 (21), Tg(gata1a:DsRed)sd2Tg (40), and Tg(kdrl:GFP)s843Tg (41) were described before. Unless otherwise specified, embryos were raised in Holtfreter's solution at 28.5 °C and staged as described previously (42). Ethical approval was obtained from the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tsinghua University.

Fish Breeding, Mutagenesis, Screening, and Mapping

WT Tuebingen males aged 4–8 months were mutagenized and bred as described (43, 44). When a mutant was identified, the F2 heterozygotes were crossed to Tg(fli1a:EGFP) or Tg(kdrl:GFP;gata1a:DsRed) to monitor vascular system and also crossed to India strain for mapping. The gene mapping was performed as described previously (23). For genotyping, a 349-bp fragment covering the mutant site was amplified with the forward primer F(T) (5′-TACGGCTTGCATGAGCTGCT-3′ for the WT allele) or F(G) (5′-TACGGCTTGCATGAGCTGCG-3′ for the mutant allele) and the reverse primer (5′-TCTGGATTTGCCATGCTCGT-3′). Mutants beyond about 36 hpf were identified by morphological changes.

Constructs

Unless specific stated, cDNAs were of the zebrafish origin and the transcript variant X5 of gbf1 was used in this study. For in vitro mRNA synthesis, the coding sequence plus 5′- and 3′-UTR of zebrafish gbf1 was amplified and cloned into the pXT7 vector using enzymatic assembly method (45). For overexpression in HeLa cells, full-length coding sequence of gbf1 was amplified and cloned in to pCS2(+) vector with a Flag tag at the N terminus. The gbf1 mutant form with a T → G nucleotide substitution at +3737, which resulted in L1246R substitution in the HDS2 domain of Gbf1 protein, and the GCA-resistant form with an A → C nucleotide substitution at +2488, which resulted in M830L substitution in Gbf1 protein, were made by site-directed mutation. The coding sequence of zebrafish arf1 was amplified and cloned into pEGFP-N3 vector (Clontech) to generate GFP-targeted Arf1 at the C terminus. For making gbf1 in situ probe, a 3′ fragment of the coding region was amplified (5′-TCCCGCACAGGATACTCAGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-GAAACGAGGAGAGGCAACCA-3′ (reverse)) and inserted into the EZ-T vector (catalog no. T168-10, Genstar).

Antibodies and Reagents

Following antibodies were used: mouse anti-Flag (catalog no. F1804, Sigma-Aldrich), rabbit anti-Flag (catalog no. F7425, Sigma-Aldrich), mouse anti-GFP antibody (catalog no. sc-9996, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-GM130 (catalog no. 610822, BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-β-COP (catalog no. ab2899, Abcam), and secondary antibodies conjugated with DyLight fluorescent dyes (488/549/649) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). N-Phenylthiourea (PTU, catalog no. P7629), and Tricaine methane sulfonate MS-222 (catalog no. E10521) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. O-Dianisidine (catalog no. D9143, Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in 100% ethanol at a final concentration of 1.5 mg/ml. Brefeldin A (catalog no. S7046, Selleck Chemicals), Golgicide A (catalog no. S7266, Selleck Chemicals), and GSK2656157 (catalog no. S7033, Selleck Chemicals) were dissolved in DMSO. TUDCA (catalog no. S7896, Selleck Chemicals) was dissolved in PBS.

RT-PCR and Real Time Quantitative PCR

RT-PCR and real time quantitative PCR were performed to check mRNA expression levels of the tested genes. The primer sequences were: for gbf1, 5′-TGGACAAGTACATGCACGCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGTCTGTTCGATCACCGTTGG-3′ (reverse); for β-actin, 5′-GCCTTCCTTCCTGGGTATGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAAGATGGAGCCACCGAT-3′ (reverse); for cdh5, 5′-TGGAATGAGTGTCAGTGCCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAAGAGCTGAGGGAACCAGC-3′ (reverse); for copa, 5′-GTCTCGCTGACCTCATCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGTGAAATACGCCGCCATC-3′ (reverse); for arcn1a, 5′-ACACTGCGTCTCTTCTCACG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTCCACGCTCAGTATCTCGC-3′ (reverse); for arcn1b, 5′-GTGTCTCAAGGTCCTGTCCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGGAGATTGGATCGTCGGC-3′ (reverse); and for copg2, 5′-CTGGGTCCCCTGTTCAAGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCGTCATCATCAGGCTCTCC-3′ (reverse); for ddit3, 5′-TCCCGTTCGCCTTCTCTAAAC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCGTCCCCTTCTCTACGTG-3′ (reverse); for baxb, 5′-TCGGTGACAAACTCGACCAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGACCATCTTGGCTGACAGT-3′ (reverse); for badb, 5′-ACATTGGGACACAGATCACCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTTTCTGTGCCGACCCACTC-3′ (reverse); and for bcl2a, 5′-AACCGACTCTTTCCTGCTCG-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTCAGAGTTGTTCCCTCCGC-3′ (reverse).

Morpholino, mRNA Synthesis, and Microinjection

Translation blocking morpholino (MO) targeting the 5′-UTR region of gbf1 (gbf1-tMO: 5′-TTGTCATACCCTGCTGTTTTTCTGT-3′) was designed and synthesized from GeneTools, LLC. The other morpholino sequences include tp53-tMO, 5′-GACCTCCTCTCCACTAAACTACGAT-3′ (46); badb-sMO, 5′-AGCCCTTGAGACTCACTCACCTTTC-3′ (47); baxb-tMO, 5′-ATTTTTCGGCTAAAACGTGTATGGG-3′ (48); and ddit3-sMO, 5′-CGATTCCAGACGCTACTGACCTCTG-3′ (49).

Capped mRNAs were synthesized using T7 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion) and purified using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. MO and mRNA were injected into the yolk of embryos at the one-cell stage with the typical MPPI-2 quantitative injection equipment. The injection dose was the amount of the MO or mRNA received by a single embryo. Because a higher dose (≥150 pg) of gbf1 mRNA led to pleiotropic developmental defects, a lower but effective dose (100 pg) was applied in rescue experiment.

Whole Mount in Situ Hybridization and O-Dianisidine Staining

Embryos were incubated in Holtfreter's solution containing 0.003% PTU to inhibit melanization from the bud stage to the desired stage. Digoxigenin-labeled probe was synthesized for in situ hybridization. O-Dianisidine staining was carried out as described with a small modification (50). Images were acquired under a stereomicroscope.

Generation of gbf1 Mutants by Cas9 Knock-out

The Cas9 target sequences (gRNAs) were predicted using the online CRISPR design tool. The codon-optimized Cas9 mRNA and gRNA were synthesized and injected as described (51, 52). The efficiency of mutations was evaluated using T7 endonuclease I (catalog no. M0302L, NEB) to digest the annealed PCR products. The gRNA targeting the 23rd exon (5′-AGCGAACAATCAGGGCTCAGAGG-3′) was co-injected with Cas9 mRNA. Founder fish (F0) carrying deletion mutations and corre sponding F1 embryos were raised up. F1 fish were crossed to gbf1tsu3994/+ to identify mutants with a phenotype.

Embryonic Cell Transplantation

Embryos from crosses between Tg(kdrl:GFP);gbf1tsu3994/+ heterozygotes or between Tg(kdrl:mCherry) WT transgenic fish were dechorionated at the shield stage, and cells at the ventral blastodermal margin were transplanted to a similar region in a host embryo as described before (53). Transplanted embryos were cultured in Holtfreter's solution containing 0.003% PTU and 0.1% penicillin/streptomycin in a 48-well plate with the bottom covered by 1% agarose. Individual donors and hosts were genotyped by PCR at later stages. Transplanted ECs were counted and imaged at 48 and 60 hpf under a Zeiss710 confocal microscope.

Fluorescence Imaging and Time Lapse Imaging

The embryos to be imaged were incubated in Holtfreter's solution containing 0.003% PTU starting from the bud stage. Tg(fli1a:EGFP) transgenic embryos at 48 hpf for vascular monitor were immobilized in 1% low melting point agarose containing 0.02% MS-222 and imaged with Zeiss710 or Zeiss710 META confocal microscope. Tg(kdrl:GFP;gata1a:DsRed) embryos were used for time lapse imaging from 38 to 48 hpf under Olympus FV1200 confocal microscope.

Cell Sorting and RNA-seq Analysis

WT siblings and mutant embryos from crosses of Tg(kdrl:GFP); gbf1tsu3994/+ at 44 hpf were dechorionated and disintegrated completely to prepare single-cell suspension. Then kdrl:GFP+ ECs were sorted by flow cytomer (FACSAria (BD) and MoFlo XDP (BeckMan)), and positive cells were confirmed by microscopy. Total mRNAs were extracted with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) and sequenced and analyzed by BGI Co. The RNA-Seq data have been deposited in NCBI with GEO accession number GSE83987.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Immunofluorescence

These experiments were performed as described before (54, 55). For drug treatment, the transfected HeLa cells were cultured for 24 h, followed by incubation in 10 μg/ml of BFA for 10 min or in 10 μm GCA for 30 min or 12 h as indicated in corresponding figure legends. Immunofluorescence images of cultured cells were acquired with Zeiss710 or Zeiss710 META confocal microscope. The Z projections of confocal stacks were generated using microscope-integrated software or Imaris.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t tests (two-tailed, unequal variance) were performed in Microsoft Excel to determine the statistical significance of the differences. Quantitative data were presented as means ± S.D.

Author Contributions

J. C. and A. M. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; J. C., X. W., and L. Y. screened mutants; J. C., L. Y., and L. Z. mapped the gene; J. Q. helped with time lapse imaging and cell sorting; X. L. helped with the experiments in mammalian cells; and S. J. discussed and helped with experiment design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Nathan D. Lawson (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA), Bo Zhang (Peking University), Catherine L. Jackson (Institut Jacques Monod, Paris, France), Holger Gerhardt (Max-Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, Berlin, Germany), and Ilse Geudens (KU Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) for providing experimental materials or protocols. We also thank the other members of Meng Lab for discussion, staff at the Cell Facility in Tsinghua Center of Biomedical Analysis for assistance with imaging and cell sorting, and Yun Li (State Key Laboratory of Membrane Biology) for technical assistance with image processing.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31330052 and Major Science Programs of the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China Grants 2012CB945101 and 2011CB943800. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

The amino acid sequence of this protein can be accessed through NCBI Protein Database under NCBI accession number XP_009305383.

This article contains supplemental Movies S1 and S2.

- ARF

- ADP-ribosylation factor

- Gbf1

- Golgi brefeldin A-resistant factor 1

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- EC

- endothelial cell

- BFA

- brefeldin A

- TUDCA

- tauroursodeoxycholic acid

- Mt

- mutant

- ERGIC

- ER-Golgi intermediate compartment

- hpf

- h postfertilization

- ISV

- intersegmental vessel

- CtA

- central artery

- PTU

- N-phenylthiourea

- MO

- morpholino

- COPI

- coat protein complex I

- ENU

- N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea.

References

- 1. D'Arcangelo J. G., Stahmer K. R., and Miller E. A. (2013) Vesicle-mediated export from the ER: COPII coat function and regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 2464–2472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lippincott-Schwartz J., Yuan L. C., Bonifacino J. S., and Klausner R. D. (1989) Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell 56, 801–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Popoff V., Adolf F., Brügger B., and Wieland F. (2011) COPI budding within the Golgi stack. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a005231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aridor M., and Hannan L. A. (2000) Traffic jam: a compendium of human diseases that affect intracellular transport processes. Traffic 1, 836–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aridor M., and Hannan L. A. (2002) Traffic jams II: an update of diseases of intracellular transport. Traffic 3, 781–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aridor M. (2007) Visiting the ER: the endoplasmic reticulum as a target for therapeutics in traffic related diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 59, 759–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schimmöller F., Itin C., and Pfeffer S. (1997) Vesicle traffic: get your coat! Curr. Biol. 7, R235–R237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Myers K. R., and Casanova J. E. (2008) Regulation of actin cytoskeleton dynamics by Arf-family GTPases. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 184–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. D'Souza-Schorey C., and Chavrier P. (2006) ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Donaldson J. G., and Jackson C. L. (2011) ARF family G proteins and their regulators: roles in membrane transport, development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 12, 362–375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Claude A., Zhao B. P., Kuziemsky C. E., Dahan S., Berger S. J., Yan J. P., Armold A. D., Sullivan E. M., and Melançon P. (1999) GBF1: a novel Golgi-associated BFA-resistant guanine nucleotide exchange factor that displays specificity for ADP-ribosylation factor 5. J. Cell Biol. 146, 71–84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kawamoto K., Yoshida Y., Tamaki H., Torii S., Shinotsuka C., Yamashina S., and Nakayama K. (2002) GBF1, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for ADP-ribosylation factors, is localized to the cis-Golgi and involved in membrane association of the COPI coat. Traffic 3, 483–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wright J., Kahn R. A., and Sztul E. (2014) Regulating the large Sec7 ARF guanine nucleotide exchange factors: the when, where and how of activation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 71, 3419–3438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Szul T., Grabski R., Lyons S., Morohashi Y., Shestopal S., Lowe M., and Sztul E. (2007) Dissecting the role of the ARF guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1 in Golgi biogenesis and protein trafficking. J. Cell Sci. 120, 3929–3940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manolea F., Claude A., Chun J., Rosas J., and Melançon P. (2008) Distinct functions for Arf guanine nucleotide exchange factors at the Golgi complex: GBF1 and BIGs are required for assembly and maintenance of the Golgi stack and trans-Golgi network, respectively. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 523–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Citterio C., Vichi A., Pacheco-Rodriguez G., Aponte A. M., Moss J., and Vaughan M. (2008) Unfolded protein response and cell death after depletion of brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein GBF1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2877–2882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Belov G. A., Kovtunovych G., Jackson C. L., and Ehrenfeld E. (2010) Poliovirus replication requires the N-terminus but not the catalytic Sec7 domain of ArfGEF GBF1. Cell Microbiol. 12, 1463–1479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goueslain L., Alsaleh K., Horellou P., Roingeard P., Descamps V., Duverlie G., Ciczora Y., Wychowski C., Dubuisson J., and Rouillé Y. (2010) Identification of GBF1 as a cellular factor required for hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J. Virol. 84, 773–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iglesias N. G., Mondotte J. A., Byk L. A., De Maio F. A., Samsa M. M., Alvarez C., and Gamarnik A. V. (2015) Dengue virus uses a non-canonical function of the host GBF1-Arf-COPI system for capsid protein accumulation on lipid droplets. Traffic 16, 962–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Wilde A. H., Wannee K. F., Scholte F. E., Goeman J. J., Ten Dijke P., Snijder E. J., Kikkert M., and van Hemert M. J. (2015) A kinome-wide small interfering RNA screen identifies proviral and antiviral host factors in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication, including double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase and early secretory pathway proteins. J. Virol. 89, 8318–8333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawson N. D., and Weinstein B. M. (2002) In vivo imaging of embryonic vascular development using transgenic zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 248, 307–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Isogai S., Horiguchi M., and Weinstein B. M. (2001) The vascular anatomy of the developing zebrafish: an atlas of embryonic and early larval development. Dev. Biol. 230, 278–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhou Y., and Zon L. I. (2011) The zon laboratory guide to positional cloning in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol. 104, 287–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mouratou B., Biou V., Joubert A., Cohen J., Shields D. J., Geldner N., Jürgens G., Melançon P., and Cherfils J. (2005) The domain architecture of large guanine nucleotide exchange factors for the small GTP-binding protein Arf. BMC Genomics 6, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sáenz J. B., Sun W. J., Chang J. W., Li J., Bursulaya B., Gray N. S., and Haslam D. B. (2009) Golgicide A reveals essential roles for GBF1 in Golgi assembly and function. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 157–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Niu T. K., Pfeifer A. C., Lippincott-Schwartz J., and Jackson C. L. (2005) Dynamics of GBF1, a brefeldin A-sensitive Arf1 exchange factor at the Golgi. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 1213–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Szul T., Garcia-Mata R., Brandon E., Shestopal S., Alvarez C., and Sztul E. (2005) Dissection of membrane dynamics of the ARF-guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Traffic 6, 374–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Quilty D., Gray F., Summerfeldt N., Cassel D., and Melançon P. (2014) Arf activation at the Golgi is modulated by feed-forward stimulation of the exchange factor GBF1. J. Cell Sci. 127, 354–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cherfils J., and Melançon P. (2005) On the action of Brefeldin A on Sec7-stimulated membrane-recruitment and GDP/GTP exchange of Arf proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33, 635–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gautier R., Douguet D., Antonny B., and Drin G. (2008) HELIQUEST: a web server to screen sequences with specific α-helical properties. Bioinformatics 24, 2101–2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. García-Mata R., Szul T., Alvarez C., and Sztul E. (2003) ADP-ribosylation factor/COPI-dependent events at the endoplasmic reticulum-Golgi interface are regulated by the guanine nucleotide exchange factor GBF1. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 2250–2261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Marciniak S. J., Yun C. Y., Oyadomari S., Novoa I., Zhang Y., Jungreis R., Nagata K., Harding H. P., and Ron D. (2004) CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 18, 3066–3077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yang E., Zha J., Jockel J., Boise L. H., Thompson C. B., and Korsmeyer S. J. (1995) Bad, a heterodimeric partner for Bcl-XL and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell 80, 285–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Oltvai Z. N., Milliman C. L., and Korsmeyer S. J. (1993) Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell 74, 609–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xie Q., Khaoustov V. I., Chung C. C., Sohn J., Krishnan B., Lewis D. E., and Yoffe B. (2002) Effect of tauroursodeoxycholic acid on endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced caspase-12 activation. Hepatology 36, 592–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Huizing M., Helip-Wooley A., Westbroek W., Gunay-Aygun M., and Gahl W. A. (2008) Disorders of lysosome-related organelle biogenesis: clinical and molecular genetics. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 9, 359–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wei A. H., He X., and Li W. (2013) Hypopigmentation in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. J. Dermatol 40, 325–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang S., Meyer H., Ochoa-Espinosa A., Buchwald U., Onel S., Altenhein B., Heinisch J. J., Affolter M., and Paululat A. (2012) GBF1 (Gartenzwerg)-dependent secretion is required for Drosophila tubulogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 125, 461–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bouvet S., Golinelli-Cohen M. P., Contremoulins V., and Jackson C. L. (2013) Targeting of the Arf-GEF GBF1 to lipid droplets and Golgi membranes. J. Cell Sci. 126, 4794–4805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Traver D., Paw B. H., Poss K. D., Penberthy W. T., Lin S., and Zon L. I. (2003) Transplantation and in vivo imaging of multilineage engraftment in zebrafish bloodless mutants. Nat. Immunol. 4, 1238–1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jin S. W., Beis D., Mitchell T., Chen J. N., and Stainier D. Y. (2005) Cellular and molecular analyses of vascular tube and lumen formation in zebrafish. Development 132, 5199–5209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B., and Schilling T. F. (1995) Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn 203, 253–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mullins M. C., Hammerschmidt M., Haffter P., and Nüsslein-Volhard C. (1994) Large-scale mutagenesis in the zebrafish: in search of genes controlling development in a vertebrate. Curr. Biol. 4, 189–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jin P., Tian T., Sun Z., and Meng A. (2004) Generation of mutants with developmental defects in zebrafish by ENU mutagenesis. Chinese Sci. Bull. 49, 2154–2158 [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gibson D. G., Young L., Chuang R. Y., Venter J. C., Hutchison C. A. 3rd, and Smith H. O. (2009) Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 6, 343–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Robu M. E., Larson J. D., Nasevicius A., Beiraghi S., Brenner C., Farber S. A., and Ekker S. C. (2007) p53 activation by knockdown technologies. PLoS Genet. 3, e78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Toruno C., Carbonneau S., Stewart R. A., and Jette C. (2014) Interdependence of Bad and Puma during ionizing-radiation-induced apoptosis. PLoS ONE 9, e88151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kratz E., Eimon P. M., Mukhyala K., Stern H., Zha J., Strasser A., Hart R., and Ashkenazi A. (2006) Functional characterization of the Bcl-2 gene family in the zebrafish. Cell Death Differ. 13, 1631–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pyati U. J., Gjini E., Carbonneau S., Lee J. S., Guo F., Jette C. A., Kelsell D. P., and Look A. T. (2011) p63 mediates an apoptotic response to pharmacological and disease-related ER stress in the developing epidermis. Dev. Cell 21, 492–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li X., Jia S., Wang S., Wang Y., and Meng A. (2009) Mta3-NuRD complex is a master regulator for initiation of primitive hematopoiesis in vertebrate embryos. Blood 114, 5464–5472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chang N., Sun C., Gao L., Zhu D., Xu X., Zhu X., Xiong J. W., and Xi J. J. (2013) Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in zebrafish embryos. Cell Res. 23, 465–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Xiao A., Wang Z., Hu Y., Wu Y., Luo Z., Yang Z., Zu Y., Li W., Huang P., Tong X., Zhu Z., Lin S., and Zhang B. (2013) Chromosomal deletions and inversions mediated by TALENs and CRISPR/Cas in zebrafish. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jia S., Ren Z., Li X., Zheng Y., and Meng A. (2008) smad2 and smad3 are required for mesendoderm induction by transforming growth factor-β/nodal signals in zebrafish. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 2418–2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liu X., Xiong C., Jia S., Zhang Y., Chen Y. G., Wang Q., and Meng A. (2013) Araf kinase antagonizes Nodal-Smad2 activity in mesendoderm development by directly phosphorylating the Smad2 linker region. Nat. Commun. 4, 1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liu X., Wang Q., and Meng A. (2016) Detection of Smad signaling in zebrafish embryos. Methods Mol. Biol. 1344, 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.