Immune checkpoint inhibitors have emerged as promising therapeutic agents in non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Programmed cell death protein‐1/programmed cell death ligand‐1 inhibitors have produced significant improvements in overall survival compared with single‐agent docetaxel, effectively establishing a new standard of care in NSCLC. An overview of the rationale for checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer, recent clinical trial data, and the need for predictive biomarkers is provided.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Non‐small cell lung cancer, Immune therapy, Programmed cell death protein‐1 inhibitors, Checkpoint inhibition, Cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4

Abstract

Historically, lung cancer was long considered a poorly immunogenic malignancy. In recent years, however, immune checkpoint inhibitors have emerged as promising therapeutic agents in non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). To date, the best characterized and most therapeutically relevant immune checkpoints have been cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4 (CTLA‐4) and the programmed cell death protein‐1 (PD‐1) pathway. In early studies, PD‐1/programmed cell death ligand‐1 (PD‐L1) inhibitors demonstrated promising antitumor activity and durable clinical responses in a subset of patients. Based on these encouraging results, multiple different PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors have entered clinical development, and two agents (nivolumab and pembrolizumab) have gained regulatory approval in the United States for the treatment of NSCLC. In several large, randomized studies, PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors have produced significant improvements in overall survival compared with single‐agent docetaxel delivered in the second‐line setting, effectively establishing a new standard of care in NSCLC. In the present report, we provide an overview of the rationale for checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer, recent clinical trial data, and the need for predictive biomarkers.

Implications for Practice.

Strategies targeting negative regulators (i.e., checkpoints) of the immune system have demonstrated significant antitumor activity across a range of solid tumors. In non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), programmed cell death protein‐1 (PD‐1) pathway inhibitors have entered routine clinical use because of the results from recent randomized studies demonstrating superiority against single‐agent chemotherapy in previously treated patients. The present report provides an overview of immune checkpoint inhibitors in lung cancer for the practicing clinician, focusing on the rationale for immunotherapy, recent clinical trial data, and future directions.

Introduction

The earliest attempts at cancer immunotherapy are widely credited to William Coley, a New York surgeon practicing in the late 19th century [1]. Inspired by reports of rare spontaneous tumor regressions in sarcoma patients developing erysipelas, Coley began performing intratumoral injections of live or inactivated Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcescens in patients with inoperable malignancies [2]. These so‐called Coley's toxins were intended to stimulate the body's “resisting powers” and kill bystander tumor cells. Although Coley reported sometimes dramatic and durable responses to these toxins [3], his work commonly drew criticism from contemporaries for a lack of reproducibility, the potential for significant toxicity, and a lack of scientific rigor in his methods and reporting. Nonetheless, Coley's work stands as the earliest attempts to harness the immune system to target cancer therapeutically.

In the ensuing decades after Coley's work, approaches to cancer immunotherapy typically consisted of anticancer vaccines and nonspecific immune stimulants (e.g., interferon‐γ) [4], [5].

However, as our collective understanding of cancer immunology has evolved, more promising forms of immunotherapy have emerged. In particular, strategies targeting negative regulators (i.e., checkpoints) of the immune system have demonstrated significant antitumor activity across a range of solid tumors, including non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)—a malignancy long considered poorly immunogenic [6], [7]. In recent years, checkpoint inhibitors targeting the programmed cell death protein‐1 (PD‐1)/programmed cell death ligand‐1 (PD‐L1) axis have shown significant antitumor activity in NSCLC [8], [9]. In this report, we provide an overview of the rationale for checkpoint inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy with a focus on NSCLC. We also detail several recent landmark studies that led to regulatory approval of the PD‐1 inhibitors nivolumab and pembrolizumab.

Immune Checkpoints in Cancer

The immune system has long been thought to play an important role in the surveillance and rejection of malignancies [10]. Cancer cells commonly possess genetic and/or epigenetic alterations that can lead to the generation of neoantigens, which can be recognized as “non‐self” by the host immune system. However, such responses can be limited by multiple mechanisms of immune suppression that render antitumor immunity ineffective. To date, various mechanisms have been proposed, including (a) downregulation of antigen‐presenting machinery, (b) immunoediting (i.e., T‐cell recognition of tumor‐specific antigens leads to outgrowth of clones lacking immunodominant antigens), (c) induction of self‐tolerance (i.e., tumor‐specific T cells are unable to kill antigen‐expressing tumor cells), and (d) upregulation of immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment [11].

Recent cancer immunotherapy efforts have focused on immune checkpoints. T‐cell activation is a tightly regulated process that involves a balance between costimulatory and coinhibitory signals [12]. Coinhibitory signals (i.e., immune checkpoints) serve to maintain self‐tolerance and avoid destruction of normal host tissue. However, such signaling interactions can be co‐opted by tumors, facilitating immune escape [13]. This vulnerability has formed the basis for the development of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies targeting immune checkpoints. Ultimately, immune checkpoint inhibitors target the “brakes” on the immune system, with the goal of inducing immune cell proliferation and activation against cancer cells [14]. To date, the best characterized and most therapeutically relevant immune checkpoints are cytotoxic T‐lymphocyte‐associated antigen 4 (CTLA‐4) and programmed cell death protein‐1.

CTLA‐4

Under normal conditions, two immunologic signals are required for T‐cell activation: (a) engagement of major histocompatibility complex‐bound antigen on antigen‐presenting cells (APCs) by the T‐cell receptor (TCR), and (b) costimulation via B7‐CD28 interactions [15]. The first signal generates specificity, and the latter amplifies TCR signaling, leading to T‐cell activation. T‐cell activation also induces a parallel, inhibitory pathway mediated by CTLA‐4 that can attenuate and terminate such responses. CTLA‐4 is a CD28 homolog that is expressed exclusively on T cells [16], [17]. CTLA‐4 leads to downregulation of T‐cell responses through several mechanisms, including outcompeting CD28 for binding of B7 molecules, inhibiting interleukin‐2 production, and preventing cell cycle progression [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. The importance of CTLA‐4 as a negative regulator of T‐cell responses is highlighted by CTLA‐4 knockout mice, which display a fatal phenotype of widespread lymphoproliferation and immune hyperactivation [23], [24]. Despite the fatal phenotype of CTLA‐4 knockout mice, however, preclinical studies demonstrated that anti‐ CTLA‐4 antibodies had a therapeutic window [25].

PD‐1/PD‐L1 Axis

Like CTLA‐4, PD‐1 is an immune checkpoint that has emerged as an important therapeutic target. PD‐1 is expressed on the surface of activated T cells, B cells, and natural killer cells [26]. Interaction of PD‐1 with one of its two known ligands, PD‐L1 and PD‐L2, leads to disruption of intracellular signaling and downregulation of effector T‐cell function [27], [28]. PD‐L2 is predominantly expressed on APCs, and PD‐L1 can be expressed on various cell types, including T cells, epithelial cells, and endothelial cells. PD‐L1 expression can also be upregulated on tumor cells [29] and other cells in the local tumor environment [30], [31]. PD‐L1 expression has been reported across a range of malignancies [32], including NSCLC [33]. Thus, the PD‐1axis can be exploited by tumors or during long‐term antigen exposure to limit immune responses. Although CTLA‐4 predominantly functions more proximally at the stage of initial T‐cell activation, PD‐1 is thought to regulate effector T‐cell function within tissues and tumors [12]. As a result, PD‐1 knockout mice generally have a milder autoimmune phenotype compared with CTLA‐4 deficient mice, characterized by end‐organ damage from T‐cell activation [34], [35].

Therapeutic Targeting of Immune Checkpoints in Lung Cancer

CTLA‐4 Blockade

CTLA‐4 was the first immune checkpoint targeted therapeutically. In advanced melanoma, the CTLA‐4 antagonist ipilimumab produced improvements in overall survival (OS) in two large phase III trials [36], [37], culminating in regulatory approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011. Despite this activity in melanoma, CTLA‐4 antagonists have shown minimal single‐agent activity in NSCLC [38]. More recently, however, ipilimumab has shown more promising results when combined with cytotoxic chemotherapy in NSCLC [39]. In a phase II trial conducted by Lynch et al., patients with treatment‐naïve, advanced NSCLC were randomized to receive carboplatin/paclitaxel with or without ipilimumab [39]. Two different dosing schemes of ipilimumab were used: concurrent ipilimumab or phased ipilimumab. Patients receiving concurrent ipilimumab were treated with four cycles of ipilimumab and carboplatin/paclitaxel, followed by two cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel alone. In contrast, patients in the phased arm received two cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel alone, followed by four cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel and ipilimumab.

Using a primary end point of immune‐related progression free survival (irPFS), Lynch et al. observed no difference in irPFS between the concurrent ipilimumab and control arms (hazard ratio [HR], 0.81; p =.13); however, phased ipilimumab significantly improved irPFS compared with the control (median, 5.7 months vs. 4.6 months, respectively; HR, 0.72; p =.05) [39]. Although the degree of irPFS improvement in their study was modest, these results prompted the initiation of a phase III trial evaluating the combination of carboplatin/paclitaxel plus phased ipilimumab in previously untreated patients with squamous histology (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02279732). In addition to this approach, significantly more enthusiasm has surrounded the use of CTLA‐4 antagonists (e.g., ipilimumab, tremelimumab) in combination with other immunotherapies, most notably PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors. We report on such combinations in our discussion of dual checkpoint inhibition in a later section.

PD‐1 Inhibitors

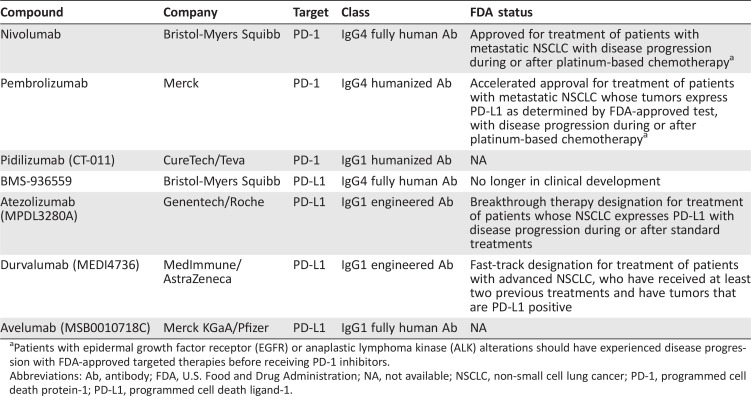

Two classes of antibodies targeting the PD‐1/PD‐L1 axis have entered clinical development: PD‐1 inhibitors and PD‐L1 inhibitors (Table 1). The former agents target the PD‐1 receptor on activated immune cells, blocking its interaction with two ligands, PD‐L1 and PD‐L2. In contrast, PD‐L1 inhibitors block the interaction between PD‐L1 and PD‐1 and the interaction between PD‐L1 and B7.1 (an inhibitory receptor on T cells). We begin with a discussion of PD‐1 inhibitors in NSCLC.

Table 1. Select PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors currently in clinical development in non‐small cell lung cancer.

Patients with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) alterations should have experienced disease progression with FDA‐approved targeted therapies before receiving PD‐1 inhibitors.

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NA, not available; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; PD‐1, programmed cell death protein‐1; PD‐L1, programmed cell death ligand‐1.

Nivolumab.

Nivolumab (BMS‐936558/MDX‐1106/ONO‐4538) is a fully human immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4) PD‐1 inhibitor [40]. In a pivotal phase I study of nivolumab [6], 122 patients with advanced NSCLC received nivolumab at doses of 1–10 mg/kg once every 2 weeks. Common adverse events (AEs) included fatigue, decreased appetite, and diarrhea [41]. Patients enrolled in the study had generally been heavily pretreated, with 55% having received three or more lines of previous therapy. Nonetheless, the objective response rate (ORR) was 17% across all dose levels. Moreover, the median duration of response (DOR) with nivolumab was impressive at 17 months, suggesting that PD‐1 inhibition might generate more durable responses compared with those seen with conventional therapies.

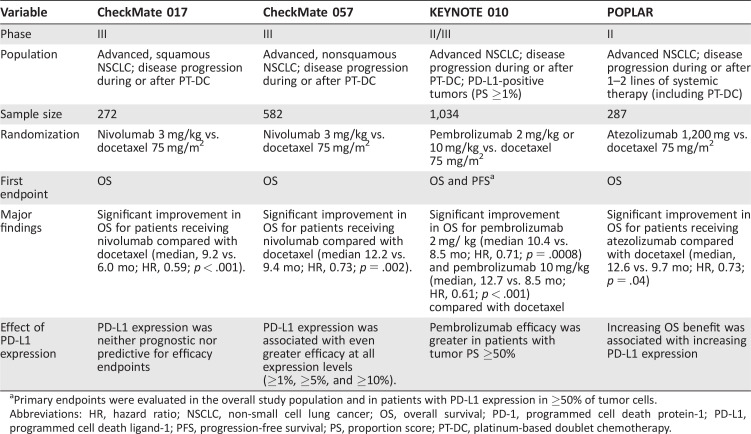

More recently, two large phase III trials of nivolumab in NSCLC have reshaped the therapeutic landscape of the disease: CheckMate 017 and CheckMate 057 [8], [9]. CheckMate 017 was a phase III, randomized trial for patients with advanced, squamous NSCLC and disease progression during or after first‐line, platinum‐based chemotherapy [8]. The study enrolled 272 patients, randomizing subjects to treatment with either nivolumab or docetaxel. The primary endpoint was OS. In January 2015, an independent data and safety monitoring committee (DSMC) recommended early termination of the study because a prespecified interim analysis demonstrated that the primary endpoint had been met. Specifically, nivolumab produced a significant improvement in OS compared with docetaxel (median, 9.2 vs. 6.0 months, respectively; HR, 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.79; p < .001). Key secondary endpoints included ORR and PFS, both of which favored the nivolumab arm. The ORR was 20% among patients receiving nivolumab versus 9% for those receiving docetaxel. The corresponding median PFS was 3.5 months versus 2.8 months (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.47–0.81; p < .001). Also, treatment‐related AEs occurred less frequently in the nivolumab arm than in the docetaxel arm. Grade 3/4 AEs were seen in only 7% of patients in the nivolumab group compared with 55% in the docetaxel group. However, comparisons of certain toxicities (e.g., cytopenias) are complicated by the significant differences in the mechanisms of action between the agents. Nonetheless, collectively, these data helped form the basis for the regulatory approval of nivolumab for previously treated squamous NSCLC.

Shortly after the report of the CheckMate 017 study, findings from a companion study, CheckMate 057, were presented [9]. CheckMate 057 was a randomized, international phase III study that enrolled patients with nonsquamous NSCLC with progression during or after platinum‐based chemotherapy. In total, 582 patients were randomized to receive either nivolumab or docetaxel. The primary endpoint was OS. Based on an interim analysis (minimum OS follow‐up of 13.2 months), an independent DSMC declared that OS among patients receiving nivolumab was superior to that of patients receiving docetaxel. Specifically, among patients receiving nivolumab, the median OS was 12.2 months (95% CI, 9.7–15.0) versus 9.4 months (95% CI, 8.0–10.7) in the docetaxel group (HR, 0.73; 96% CI, 0.59–0.89; p = .002). Moreover, nivolumab was associated with an impressive median DOR (17.2 months). Based on these data, the U.S. FDA expanded the approved use of nivolumab in October 2015 to include patients with advanced, NSCLC whose disease had progressed during or after platinum‐based chemotherapy (Table 2).

Table 2. Randomized studies of PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors in non‐small cell lung cancer.

Primary endpoints were evaluated in the overall study population and in patients with PD‐L1 expression in ≥50% of tumor cells.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NSCLC, non‐small cell lung cancer; OS, overall survival; PD‐1, programmed cell death protein‐1; PD‐L1, programmed cell death ligand‐1; PFS, progression‐free survival; PS, proportion score; PT‐DC, platinum‐based doublet chemotherapy.

Despite improvements in OS and ORR in the nivolumab arm of CheckMate 057, no difference was seen in PFS. The median PFS among patients receiving nivolumab was numerically lower than that observed among patients receiving docetaxel (2.3 vs. 4.2 months, respectively; HR, 0.92; p = .39), but this difference was not statistically significant. Nonetheless, this finding could have important implications for clinical trial designs moving forward, in particular, as investigators begin to examine PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors in the first‐line setting, in which crossover might limit the ability to observe future OS benefits.

In the CheckMate study, PD‐L1 biomarker analyses were incorporated into the study design; however, these assessments were performed retrospectively and did not factor in study eligibility. For example, in the initial phase I study by Topalian et al. [6], PD‐L1 expression was assessed using a murine monoclonal antibody (clone 5H1) and appeared to enrich for responders. Among PD‐L1‐positive subjects (PD‐L1 expression in ≥5% of tumor cells), the ORR with nivolumab was 36%. In contrast, 0 of 17 PD‐L1‐negative patients achieved a response. Furthermore, in CheckMate 057, PD‐L1 expression using a different antibody (Dako clone 28‐8) was found to predict for improved OS with nivolumab [9]. As use of PD‐L1 testing has expanded, however, it has become clear that PD‐L1 immunohistochemistry is imperfect, because responses have been observed among both PD‐L1‐positive and ‐negative patients. In CheckMate 017, nivolumab produced a survival benefit independent of PD‐L1 expression [8].

Recently, the FDA approved the Dako 28‐8 PD‐L1 assay as a complementary diagnostic test for nivolumab for patients with nonsquamous NSCLC. Of note, complementary biomarkers are distinct from companion diagnostics [42]. Complementary biomarkers provide additional information regarding who is most likely to benefit from a given drug, but they are not required for use. In contrast, companion diagnostics are considered essential for the safe and effective use of a drug [42].

In CheckMate 057, PD‐L1 expression using a different antibody (Dako clone 28‐8) was found to predict for improved OS with nivolumab. As use of PD‐L1 testing has expanded, however, it has become clear that PD‐ L1 immunohistochemistry is imperfect, because responses have been observed among both PD‐L1‐ positive and ‐negative patients.

Pembrolizumab.

Pembrolizumab is a humanized, IgG4 monoclonal antibody directed against PD‐1. The safety and activity of pembolizumab were initially evaluated in KEYNOTE‐001, a large phase I study that enrolled 495 subjects with previously treated and untreated NSCLC [43]. Patients received pembolizumab at doses of either 2 or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks or 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks. Common treatment‐related AEs were fatigue (19.4%), pruritus (10.7%), and decreased appetite (10.5%). In general, immune‐mediated events were relatively infrequent but included hypothyroidism (6.9%), pneumonitis (3.6%), and infusion‐related reactions (3%).

For all NSCLC patients in that study, the ORR was 19.4%. No difference was found in efficacy according to the dose, schedule, or histologic type. Moreover, just as with other PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors, the responses were often durable. At the time of reporting, 84.4% of responders had no evidence of disease progression (median DOR, 12.5 months; range, 1.0–23.3).

In contrast to CheckMate 017 and 057 [8], [9], KEYNOTE‐001 sought to prospectively define and validate PD‐L1 expression as a predictive biomarker for pembolizumab [43]. All patients underwent a contemporaneous biopsy, followed by enrollment into either a training group (n = 182) or a validation group (n = 313). PD‐L1 expression was evaluated using the 22C3 monoclonal antibody. On the basis of the analysis of the biopsy samples from the training group, membranous PD‐L1 expression on 50% or more tumor cells (proportion score, ≥50%) was selected as the PD‐L1 cutoff for the remainder of the trial. In total, 23.2% of patients had a proportion score (PS) of ≥50%. At that cutpoint, the ORRs with pembrolizumab were 36.6% and 45.2% in the training and validation cohorts, respectively. The median PFS among all patients with a PS of at least 50% was 6.3 months (95% CI, 2.9–12.5), including a median PFS of 12.5 months for previously untreated patients. Given this encouraging activity, pembrolizumab was granted accelerated approval by the U.S. FDA in October 2015. Specifically, pembrolizumab was approved for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC in whom previous treatments have failed and whose tumors express PD‐L1. This was accompanied by approval of the 22C3 monoclonal antibody as a companion diagnostic for determining PD‐L1 expression.

More recently, pembrolizumab was evaluated in an international phase II/III trial (KEYNOTE‐010) that enrolled patients with previously treated NSCLC [44]. In contrast to CheckMate 017 and 057 [8], [9], all patients enrolled in KEYNOTE 010 were required to have PD‐L1 expression on at least 1% of tumor cells. Altogether, 1,034 subjects were enrolled and randomized to receive pembrolizumab 2 or 10 mg/kg or docetaxel 75 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. The study had coprimary endpoints of OS and PFS in the total study population and those with high PD‐L1 expression (PS ≥50%). In the total study population, both pembrolizumab arms had significantly improved OS compared with the docetaxel arm. The median OS was 10.4 months for patients receiving pembrolizumab 2 mg/kg (HR, 0.71 vs. docetaxel; 95% CI, 0.58–0.88; p = .0008), 12.7 months for those receiving pembrolizumab 10 mg/kg (HR, 0.61 vs. docetaxel; 95% CI, 0.49–0.75; p < .0001), and 8.5 months for patients receiving docetaxel. Among the patients with high PD‐L1 expression (PS ≥50%) treated with either dose of pembrolizumab, OS was also significantly improved compared with docetaxel. Despite these improvements in OS, no difference was found in PFS among the 3 study arms. Finally, pembrolizumab demonstrated improved tolerability compared with docetaxel, with grade ≥3 AEs in 13%–16% of patients receiving pembrolizumab versus 35% of those treated with docetaxel [44]. Ultimately, the KEYNOTE studies, together with CheckMate 017 and 057, have established PD‐1 pathway blockade as a new standard of care in the management of previously treated, advanced NSCLC.

PD‐L1 Inhibitors

Atezolizumab.

Atezolizumab (MPDL‐3280A) is a high‐affinity human monoclonal IgG1 antibody directed against PD‐L1 [45]. In an initial phase I study of atezolizumab [45], treatment was generally well tolerated up to the maximum administered dose of 20 mg/kg every 3 weeks. Common treatment‐related AEs were comparable to those seen with other PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors (fatigue [24.2%], anorexia [11.9%], and pyrexia [11.6]). Among 53 efficacy‐evaluable patients with NSCLC in that study, the confirmed ORR was 21%. A significant association was seen between treatment response and PD‐L1 expression on tumor‐infiltrating immune cells; however, no association was seen with tumoral PD‐L1 expression in that study.

With the encouraging activity of atezolizumab in the initial phase I study, a phase II randomized study in NSCLC was recently completed [46]. The POPLAR study enrolled 287 patients with previously treated NSCLC, randomizing patients to receive either atezolizumab or docetaxel. Patients were stratified by PD‐ L1 status, histologic type, and previous lines of therapy. The primary endpoint was OS in the intention‐to‐treat population and PD‐L1 subgroups. Baseline PD‐L1 expression was scored by immunohistochemistry in tumor cells and tumor‐infiltrating immune cells (Table 3). In the intention‐to‐treat population, atezolizumab significantly improved OS compared with chemotherapy (median, 12.6 vs. 9.7 months; HR, 0.73; p = .04). PD‐L1 expression on tumor cells or tumor‐infiltrating immune cells was associated with an OS benefit. A phase III trial of atezolizumab (OAK study) is now ongoing in a similar patient population (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02008227). Furthermore, atezolizumab was recently granted breakthrough therapy designation by the FDA for the management of previously treated, advanced NSCLC patients whose tumors express PD‐L1.

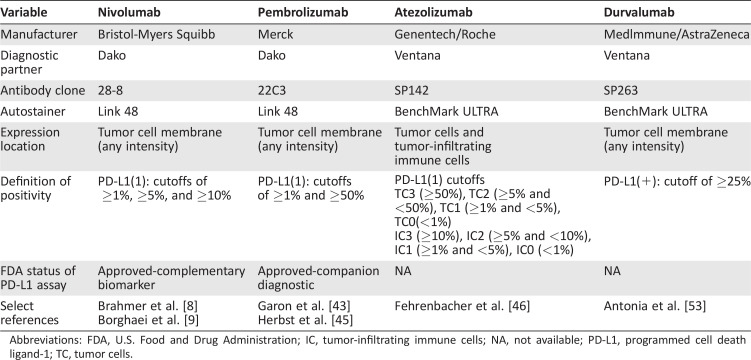

Table 3. Comparison of PD‐L1 immunohistochemical assays.

Abbreviations: FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IC, tumor‐infiltrating immune cells; NA, not available; PD‐L1, programmed cell death ligand‐1; TC, tumor cells.

Durvalumab.

Durvalumab (MEDI4736) is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against PD‐L1. In an initial phase I/II study evaluating the safety and activity of durvalumab in patients with advanced solid tumors, no maximum tolerated dose was identified [47]. As of February 2015, 228 patients with NSCLC had been enrolled and treated in the 10‐mg/kg cohort. Among 200 evaluable patients, the ORR was 16%. Moreover, PD‐L1 positivity ($25% tumor cell staining) was associated with response. Durvalumab was generally well‐tolerated with treatment‐related, grade 3/4 toxicities observed in 8% of patients, with 5% leading to drug discontinuation.

Checkpoint Inhibitor Combinations

Although PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors have dramatically transformed the management of NSCLC, most patients do not respond to therapy. Consequently, focus has been placed on identifying novel treatment combinations that might increase the ORRs, generally using PD‐1 inhibitors as a therapeutic foundation. Currently, various strategies are being pursued, including PD‐1/ PD‐L1 inhibitors combined with other checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., CTLA‐4, LAG‐3, TIM‐3), costimulatory checkpoints (e.g., OX40, GITR, 4‐1BB), other immunomodulatory molecules (e.g., indoleamide 2,3‐dioxygenase [IDO]), chemotherapy, vaccines, and radiation [48]. Although a comprehensive discussion of these targets is beyond the scope of the present review, we highlight the emerging data on the use of PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors combined with CTLA‐4 blockade in NSCLC.

Dual PD‐1, CTLA‐4 Inhibition.

PD‐1 and CTLA‐4 inhibit antitumor immunity via nonredundant pathways. Early preclinical studies also suggested that combined CTLA‐4 and PD‐1 pathway blockade produced synergistic antitumor activity [49], providing the rationale for clinical studies of such combinations. In subsequent melanoma studies, the combined administration of ipilimumab and nivolumab resulted in improved antitumor activity compared with either agent alone; however, increased toxicity was also observed [50].

With the success of dual PD‐1/CTLA‐4 blockade in melanoma, similar combinations are being explored in NSCLC. In one early study evaluating nivolumab plus ipilimumab (CheckMate 012), the combination was associated with modest activity (ORR 16%) but significant toxicity, with grade 3/4 treatment‐related adverse events and treatment‐related discontinuation observed in 49% and 35% of patients, respectively [51]. However, the dose levels and schedules of nivolumab and ipilimumab (nivolumab 1/ipilimumab 3 or nivolumab 3/ipilimumab 1 mg/kg every 3 weeks, followed by nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks) initially used in CheckMate 012 were based on the experience in melanoma. The protocol was subsequently modified to evaluate alternative dose levels and frequencies. Recently, Hellmann et al. reported findings from two of these cohort (nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks plus ipilimumab 1 mg/kg every 6 or 12 weeks) at the 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting [52]. Of 77 treatment‐naïve NSCLC patients treated with nivolumab/ipilimumab in these alternative dose cohorts, the combination appeared more tolerable (treatment‐related discontinuation rates of 11%–13%). Moreover, promising antitumor activity (ORR 39%–47%) was observed. Based on such encouraging antitumor activity, the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab is being evaluated in a randomized phase III trial (CheckMate 227) against nivolumab, nivolumab plus platinum‐ based chemotherapy, and platinum‐based chemotherapy alone in PD‐L1‐defined, previously untreated NSCLC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02477826).

In addition to nivolumab/ipilimumab, other PD‐1/PD‐L1 plus CTLA‐4 combinations have been explored [53]. In a recent dose‐escalation study, 102 immunotherapy‐naïve patients with advanced NSCLC were treated with the combination of durvalumab and tremelimumab (durvalumab 3–20 mg/kg every 4 weeks or 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks and tremelimumab 1–10 mg/kg every 4 weeks for six doses, followed by every 12 weeks for three doses). Toxicity, although manageable, was frequent with 82 patients (80%) experiencing one or more treatment‐related AEs. Serious AEs occurred in 36% of patients, and 29 patients (28%) discontinued treatment because of AEs. The most frequent treatment‐related grade 3/4 adverse events included diarrhea (11%), colitis (9%), and increased lipase (8%). Based on the available safety and clinical data, durvalumab 20 mg/kg every 4 weeks plus tremelimumab 1 mg/kg every 4 weeks was selected for dose expansion. Among 63 response evaluable patients, the ORR was 17%, and antitumor activity was observed independent of PD‐L1 status. With this encouraging activity, multiple phase II/III studies have been launched in NSCLC, including the first‐line MYSTIC (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02453282) and NEPTUNE (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02542293) studies.

Predictive Biomarkers of Response

Despite the activity of PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors in NSCLC, only ∼20% of patients ultimately respond to therapy, underscoring the critical need for predictive biomarkers. As detailed, immunohistochemical assessments of PD‐L1 expression have been the most thoroughly studied to date. In general, PD‐L1 expression has been associated with higher ORRs (range, 23%–83%) to PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors [9], [43], [45], [54], but responses have also been observed among PD‐L1‐negative patients (ORRs, 9%–20%) [43], [45], [54], [55]. PD‐L1 assays have been further complicated by a lack of standardization in testing methods across agents (Table 3). Each PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitor in clinical development has used different anti‐PD‐L1 antibodies, different scoring cutoffs, and various scoring algorithms [56]. Given this lack of a reference standard for PD‐L1 testing, efforts are now ongoing to harmonize various PD‐L1 assays (e.g., International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Blueprint Project). Nonetheless, at present, PD‐L1 immunohistochemistry remains an imperfect biomarker in NSCLC.

Beyond PD‐L1 testing, various other predictive biomarkers have been explored [41], [45], [55]. For example, in early studies, tobacco exposure was associated with higher ORRs to PD‐1/ PD‐L1 inhibitors. ORRs among smokers ranged from 27% to 42%, and ORRs among never smokers ranged from 0% to 10% [41], [45], [55]. In addition, the presence of EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) mutations and ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) rearrangements (alterations typically associated with a lack of tobacco exposure) have been associated with lower ORRs to PD‐1 inhibitors [9], [44], [57]. Beyond these clinical and molecular features, Rizvi et al. recently reported baseline tumor mutational load (using whole exome sequencing) as a predictor of response to PD‐1 blockade [58]. In that study, patients with a higher tumor mutation load were more likely to experience durable clinical benefit after treatment with pembrolizumab.

Additional insights into the predictors of response to PD‐ 1/PD‐L1 inhibition have been gained through the study of melanoma. For example, Tumeh et al. demonstrated that CD8 + tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment were associated with increased responsiveness to PD‐1 inhibition [59]. In contrast, Hugo et al. termed this Innate PD‐1 RESistance (IPRES), which was associated with a lack of response to PD‐1 inhibition [60]. The genes included in this signature are involved in immunosuppression, angiogenesis, monocyte/macrophage chemotaxis, and epithelial‐mesenchymal transition. Ultimately, many of these biomarkers could be interrelated, and additional studies are necessary to prospectively validate these biomarkers.

Future Directions

Currently, PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors are being explored in several other lung cancer settings. Clinical trials evaluating PD‐1 pathway blockade as neoadjuvant/adjuvant therapy, consolidation therapy after definitive chemoradiation, and in small cell lung cancer are now ongoing and/or planned. However, the greatest focus to date has been in transitioning PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors to the first‐line setting. A number of different randomized, phase III trials evaluating PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors in treatment‐naïve patients are now ongoing. In these studies, two major clinical trial designs have emerged: (a) PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors alone versus platinum‐based chemotherapy in biomarker‐selected (i.e., PD‐L1‐positive) patients; and (b) PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors plus platinum‐based chemotherapy versus platinum‐based chemotherapy alone in unselected patient populations. Several of these studies (e.g., CheckMate 026, KEYNOTE 024) have already completed enrollment, and the results are eagerly awaited.

Clinical trials evaluating PD‐1 pathway blockade neoadjuvant/adjuvant therapy, consolidation therapy after definitive chemoradiation, and in small cell lung cancer are now ongoing and/or planned. However, the greatest focus to date has been in transitioning PD‐1/PD‐L1 inhibitors to the first‐line setting.

Conclusion

Agents targeting the PD‐1/PD‐L1 axis have transformed the management of NSCLC and emerged as a new standard of care for previously treated, advanced NSCLC. Nonetheless, a number of challenges remain. As detailed, most patients do not respond to these agents. Thus, an urgent clinical need exists to identify better predictive biomarkers. In parallel, the field has begun exploring strategies aimed at converting immunotherapy “nonresponders” to “responders.” Most of these approaches involve the use of therapeutic combinations. In addition to PD‐1/CTLA‐4 combinations, immune checkpoint inhibitors are being explored together with vaccines, other checkpoint inhibitors, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. As the experience with melanoma has taught us, however, immune checkpoint inhibitor combinations can be associated with increased and/or unexpected toxicities [50], [61]. This highlights the need for carefully designed, prospective clinical trials, rather than empiric combinations or off‐label use of such agents. Furthermore, given the sheer number of possible immunotherapy combinations in this space, novel trial designs will be necessary to identify the most promising combinations in a timely manner.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Benjamin Herzberg, Meghan J. Campo, Justin F. Gainor Provision of study material or patients: Benjamin Herzberg, Meghan J. Campo

Collection and/or assembly of data: Justin F. Gainor Data analysis and interpretation: Justin F. Gainor

Manuscript writing: Benjamin Herzberg, Meghan J. Campo, Justin F. Gainor

Final approval of manuscript: Benjamin Herzberg, Meghan J. Campo, Justin F. Gainor

Disclosures

Justin F. Gainor: Novartis, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Genentech/Roche, Clovis, Boehringer‐Ingelheim (C/A), Merck (H). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/ inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1. McCarthy EF. The toxins of William B. Coley and the treatment of bone and soft‐tissue sarcomas. Iowa Orthop J 2006;26:154–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature 2011;480:480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coley WB. II. Contribution to the knowledge of sarcoma. Ann Surg 1891;14:199–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atkins MB, Lotze MT, Dutcher JP et al. High‐dose recombinant interleukin 2 therapy for patients with metastatic melanoma: Analysis of 270 patients treated between 1985 and 1993. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:2105–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medical Research Council Renal Cancer Collaborators . Interferon‐alpha and survival in metastatic renal carcinoma: Early results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1999;353:14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti‐PD‐1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2443–2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Prado‐Garcia H, Romero‐Garcia S, Aguilar‐Cazares D et al. Tumor‐induced CD8 + T‐cell dysfunction in lung cancer patients. Clin Dev Immunol 2012; 2012:741741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous‐cell non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:123–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Borghaei H, Paz‐Ares L, Horn L et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:1627–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Finn OJ. Immuno‐oncology: Understanding the function and dysfunction of the immune system in cancer. Ann Oncol 2012;23(suppl 8):viii6–viii9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brahmer JR, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Making immunotherapy a reality for the treatment of lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2013; 1:85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:252–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fife BT, Bluestone JA. Control of peripheral T‐cell tolerance and autoimmunity via the CTLA‐Checkpoint Inhibitors in NSCL and PD‐1 pathways. Immunol Rev 2008;224: 166–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune checkpoint blockade in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1974–1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Greenwald RJ, Freeman GJ, Sharpe AH. The B7 family revisited. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:515–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brunet JF, Denizot F, Luciani MF et al. A new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily— CTLA‐4. Nature 1987;328:267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Linsley PS, Brady W, Urnes M et al. CTLA‐4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J Exp Med 1991;174:561–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY et al. CTLA‐4 can function as a negative regulator of T cell activation. Immunity 1994;1:405–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walunas TL, Bakker CY, Bluestone JA. CTLA‐4 ligation blocks CD28‐dependent T cell activation. J Exp Med 1996;183:2541–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wing K, Onishi Y, Prieto‐Martin P et al. CTLA‐4 control over Foxp31 regulatory T cell function. Science 2008;322:271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Peggs KS, Quezada SA, Chambers CA et al. Blockade of CTLA‐4 on both effector and regulatory T cell compartments contributes to the antitumor activity of anti‐CTLA‐4 antibodies. J Exp Med 2009; 206:1717–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sharpe AH, Abbas AK. T‐cell costimulation— Biology, therapeutic potential, and challenges. N Engl J Med 2006;355:973–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN et al. Loss of CTLA‐4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA‐4. Immunity 1995;3:541–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in CTLA‐4. Science 1995;270: 985–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA‐4 blockade. Science 1996;271:1734–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agata Y, Kawasaki A, Nishimura H et al. Expression of the PD‐1 antigen on the surface of stimulated mouse T and B lymphocytes. Int Immunol 1996;8:765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blank C, Brown I, Peterson AC et al. PD‐L1/B7H‐ 1 inhibits the effector phase of tumor rejection by T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic CD81 T cells. Cancer Res 2004;64:1140–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y et al. Engagement of the PD‐1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med 2000;192: 1027–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dong H, Strome SE, Salomao DR et al. Tumor‐ associated B7‐H1 promotes T‐cell apoptosis: A potential mechanism of immune evasion. Nat Med 2002;8:793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ et al. PD‐1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu Rev Immunol 2008;26:677–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ahmadzadeh M, Johnson LA, Heemskerk B et al. Tumor antigen‐specific CD8 T cells infiltrating the tumor express high levels of PD‐1 and are functionally impaired. Blood 2009;114:1537–1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zou W, Chen L. Inhibitory B7‐family molecules in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol 2008;8:467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Konishi J, Yamazaki K, Azuma M et al. B7‐H1 expression on non‐small cell lung cancer cells and its relationship with tumor‐infiltrating lymphocytes and their PD‐1 expression. Clin Cancer Res 2004; 10:5094–5100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nishimura H, Nose M, Hiai H et al. Development of lupus‐like autoimmune diseases by disruption of the PD‐1 gene encoding an ITIM motif‐carrying immunoreceptor. Immunity 1999;11: 141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nishimura H, Okazaki T, Tanaka Y et al. Autoimmune dilated cardiomyopathy in PD‐1 receptor‐deficient mice. Science 2001;291: 319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robert C, Thomas L, Bondarenko I et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2517–2526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med 2010;363: 711–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zatloukal P, Heo D, Park K et al. Randomized phase II clinical trial comparing tremelimumab (CP‐ 675,206) with best supportive care (BSC) following first‐line platinum‐based therapy in patients (pts) with advanced non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 2009;27(suppl 15):8071a. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lynch TJ, Bondarenko I, Luft A et al. Ipilimumab in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first‐line treatment in stage IIIB/IV non‐small‐cell lung cancer: Results from a randomized, double blind, multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30:2046–2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wang C, Thudium KB, Han M et al. In vitro characterization of the anti‐PD‐1 antibody nivolu‐ mab, BMS‐936558, and in vivo toxicology in nonhuman primates. Cancer Immunol Res 2014;2: 846–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gettinger SN, Horn L, Gandhi L et al. Overall survival and long‐term safety of nivolumab (antiprogrammed death 1 antibody, BMS‐936558, ONO‐ 4538) in patients with previously treated advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2015;33: 2004–2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Milne CP, Bryan C, Garafalo S et al. Complementary versus companion diagnostics: Apples and oranges. Biomarkers Med 2015;9:25–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non‐small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2018–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Herbst RS, Baas P, Kim DW et al. Pembrolizumab versus docetaxel for previously treated, PD‐L1‐ positive, advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE‐010): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1540–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti‐PD‐L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature 2014;515:563–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fehrenbacher L, Spira A, Ballinger M et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel for patients with previously treated non‐small‐cell lung cancer (POPLAR): A multicentre, open‐label, phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1837–1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rizvi NA, Brahmer JR, Ou SI et al. Safety and clinical activity of MEDI4736, an anti programmed celldeath‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) antibody, in patients with non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol 2015;33(suppl):8032a. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hellmann MD, Friedman CF, Wolchok JD. Combinatorial cancer immunotherapies. Adv Immunol 2016;130:251–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Curran MA, Montalvo W, Yagita H et al. PD‐1 and CTLA‐4 combination blockade expands infiltrating T cells and reduces regulatory T and myeloid cells within B16 melanoma tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:4275–4280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Larkin J, Chiarion‐Sileni V, Gonzalez R et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Antonia SJ, Gettinger SN, Chow LQM et al. Nivolumab (anti‐PD‐1; BMS‐936558, ONO‐ 4538) and ipilimumab in first‐line NSCLC: Interim phase I results. J Clin Oncol 2014;32(suppl):5s, 8023a. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hellmann MD, Gettinger SN, Goldman JW. CheckMate 012: Safety and efficacy of first‐line (1L) nivolumab (nivo; N) and ipilimumab (ipi; I) in advanced (adv) NSCLC. J Clin Oncol 2016;34(suppl):3001a. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Antonia S, Goldberg SB, Balmanoukian A et al. Safety and antitumour activity of durvalumab plus tremelimumab in non‐small cell lung cancer: A multicentre, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol 2016;17: 299–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Antonia S, Ou S, Khleif S et al. Clinical activity and safety of MEDI4736, an anti‐programmed cell death‐ligand 1 (PD‐L1) antibody, in patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2014;25(suppl 4):426–470. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Garon E, Gandhi L, Rizvi N et al. Antitumor activity of pembrolizumab (Pembro; MK‐3475) and correlation with programmed death ligand 1(PD‐L1) expression in a pooled analysis of patients (pts) with advanced non‐small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC). Ann Oncol 2014;25:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kerr K, Tsao M, Nicholson A et al. Programmed death‐ligand 1 immunohistochemistry in lung cancer: In what state is this art? J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:985–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gainor JF, Shaw AT, Sequist LV et al. EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements are associated with low response rates to PD‐1 pathway blockade in non‐small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): A retrospective analysis. Clin Cancer Res 2016. [E‐pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A et al. Cancer immunology: Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD‐1 blockade in non‐small cell lung cancer. Science 2015;348:124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH et al. PD‐1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature 2014;515:568–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti‐PD‐1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell 2016;165: 35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ribas A, Hodi FS, Callahan M et al. Hepatotoxicity with combination of vemurafenib and ipilimu‐ mab. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1365–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]