Improper use, storage, and disposal of prescribed opioids can lead to diversion or accidental poisoning. The present study compared 300 adult cancer outpatients receiving opioids who had also received educational material (EM) with 300 patients who had not received EM. The use of EM on opioid safety for patients with advanced cancer was associated with improved patient‐reported safe opioid use, storage, and disposal.

Keywords: Patient education, Opioid use, Opioid disposal, Opioid storage, Cancer

Abstract

Background.

Improper use, storage, and disposal of prescribed opioids can lead to diversion or accidental poisoning. Our previous study showed a large proportion of cancer patients have unsafe opioid practices. Our objective was to determine whether an improvement occurred in the patterns of use, storage, and disposal of opioids among cancer outpatients after the implementation of a patient educational program.

Patients and Methods.

Our palliative care (PC) clinic provides every patient with educational material (EM) on safe opioid use, storage, and disposal every time they receive an opioid prescription. We prospectively assessed 300 adult cancer outpatients receiving opioids in our PC clinic, who had received the EM, and compared them with 300 patients who had not received the EM. The previously used surveys pertaining to opioid use, storage, and disposal were administered, and demographic information was collected. Sharing or losing their opioids was defined as unsafe use.

Results.

Patients who received EM were more aware of the proper opioid disposal methods (76% vs. 28%; p ≤ .0001), less likely to share their opioids with someone else (3% vs. 8%; p = .0311), less likely to practice unsafe use of opioids (18% vs. 25%; p = .0344), and more likely to be aware the danger of their opioids when taken by others (p = .0099). Patients who received the EM were less likely to have unused medication at home (38% vs. 47%; p = .0497) and more likely to keep their medications in a safe place (hidden, 75% vs. 70%; locked, 14% vs. 10%; p = .0025).

Conclusion.

The use of EM on opioid safety for patients with advanced cancer was associated with improved patient‐reported safe opioid use, storage, and disposal.

Implications for Practice.

Prescription opioid abuse is a fast‐growing epidemic that has become more prominent recently, even in the cancer pain population. A previous study reported that 26% of cancer outpatients seen in the supportive care center either lose their pain medications or share their pain medications with someone else. This study demonstrates that the implementation of an opioid educational program and distribution of educational material on opioid safety brings about an improvement in opioid storage, use, and disposal practices in patients being prescribed opioids for cancer‐related pain. Our study highlights the importance of consistent and thorough opioid education at every instance in which opioids are prescribed.

Introduction

The use and abuse of prescription opioids is a growing public health problem in the United States. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimate that approximately 2 million adults abuse prescription drugs, including opioids, and that 16,000 prescription opioid‐related deaths occur every year [1], [2]. In 2012 alone, 259 million prescriptions were written. Opioid sales in the U.S. increased by 400% from 1997 to 2007 [3]. However, this exponential increase in opioid use has not been matched with an increase in drug take‐back programs for the safe disposal of unused or expired opioids [1], [3], [4]. Moreover, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have not issued uniform guidelines regarding the safe, effective, convenient, and environmentally friendly disposal of opioids [5], [6], [7]. Improper storage and disposal of opioids can lead to increased availability of these medications for abuse and accidental poisoning. According to the report by the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, approximately 75% of all opioid misuse is from people using opioids that were not prescribed for them [8]. Approximately 70% of people who abuse prescription opioids obtain them from friends or relatives and only 5% from drug dealers or strangers [3], [4].

Approximately 90% of advanced cancer patients with cancer‐related pain require treatment with opioids [9]. Throughout the course of their disease, patients can experience acute pain exacerbations, as well as adverse side effects that could necessitate opioid dose adjustments or opioid rotation [9], [10], [11]. As a consequence of these changes, patients could have in their possession multiple opioid prescriptions that could be abused or diverted.

A previous study by our group showed that a significant proportion of cancer patients receiving opioid prescriptions do not store, use, or dispose of opioids safely [12]. Universal education for all patients receiving opioids regarding safe storage, use, and disposal to minimize the risks of diversion or accidental poisoning was adopted by our palliative care (PC) clinic to address this issue. Our objective in the present study was to determine whether an improvement had occurred in the patterns of use, storage, and disposal of opioids among cancer outpatients with implementation of a patient educational program.

Patients and Methods

The present study was an institutional review board‐approved prospective cross‐sectional survey of outpatients in the PC clinic at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (UT MDACC). Consecutive patients who had attended the PC clinic for a follow‐up visit from December 2014 to December 2015 were initially screened and then approached if they were at least 18 years old; had received opioids for at least 1 month; were able to read, write, and converse in English; and had no cognitive impairment. Only those patients who were returning for a follow‐up visit to the PC clinic and were taking opioids for at least 1 month as documented in a previous clinic note were invited to participate in the study. This ensured that only those patients who had previously received a prescription of opioids and subsequent opioid education from the palliative care team were included in the study. Patients who were in acute symptom distress as determined by the attending clinic physician were excluded.

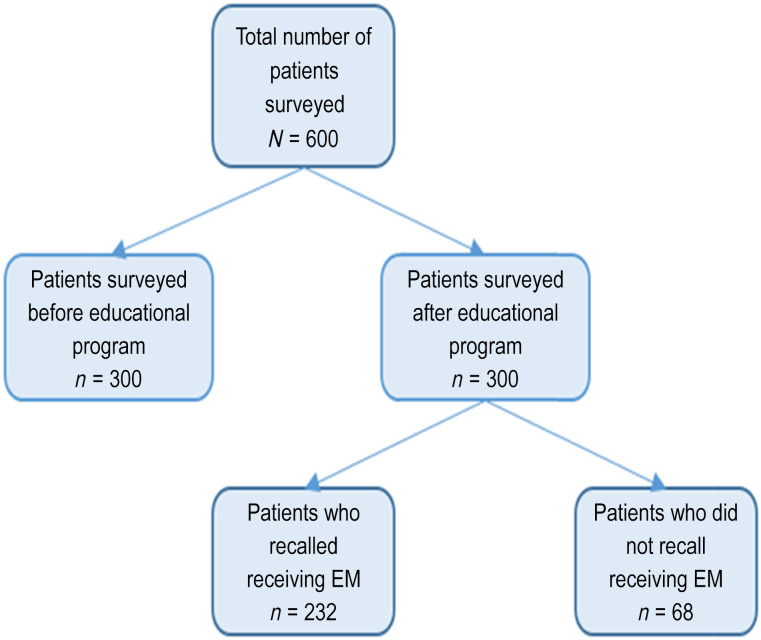

We prospectively assessed 300 adult cancer outpatients receiving opioids in our PC clinic after initiation of the educational program and compared them with 300 control patients who had completed an opioid use, disposal, and storage safety survey before the initiation of the educational program [12]. The 300 patients in the control group belonged to a previous cohort. Figure 1 illustrates the study flowchart.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart showing the different groups that were compared.

Abbreviation: EM, education material.

Education Material for all PC Clinic Patients

Our PC clinic now provides every patient with educational material (EM) on safe opioid use, storage, and disposal every time they receive an opioid prescription. This EM was created with the UT MDACC Patient Education Office. The content is based on the FDA, EPA, and DEA guidelines. This two‐paged handout is worded simply and can be understood easily by someone with at least an eighth grade level of education. Distribution of the EM was started in May 2014, 7 months before enrolling our first patient into the present study.

Educational Program for All PC Clinic Patients

The educational program consists of the EM and the personalized education and counseling given by our PC staff. Our nurses, pharmacists, and physicians received in‐service training regarding the safe practices regarding opioids and what patients and caregivers need to know. For each patient who received an opioid prescription in the PC clinic, the information contained in the EM was reviewed with that patient and their accompanying family member or caregiver. They were also given personalized education regarding safe opioid use, storage, and disposal. An overview of the general points of the EM was reviewed with the patient and caregiver. Elaboration of certain points and questions from the patient and caregiver were answered during the clinic visit.

Survey

A self‐administered survey was provided to the eligible patients by the research staff after obtaining written informed consent. Patients were informed that their responses to the survey would be kept confidential from their medical team. This survey is the same used by our group for a previous study, with the addition of a few questions pertaining to the usefulness of the EM. It comprises 23 questions related to the patient's living situation and the storage, use, and disposal of opioids. The questions were formulated by the study investigators primarily from the recommendations by the FDA and DEA, along with a review of the published data regarding the safe use, storage, and disposal of prescription pain medications [5], [6], [7]. The research staff also assessed the surveys for completeness and approached the patients regarding any uncompleted questions. The principal investigator or study collaborators interviewed the patients whose responses indicated unsafe practices to provide instruction on, and reinforcement of, the safety principles. The patients’ demographic and clinical information, including opioid prescription history, scores on the cut‐down, annoyed, guilty, eye‐opener, adapted to include drugs (CAGE‐AID), alcoholism, and drug screening questionnaires [13], [14], history of tobacco and/or illicit drug use, and the morphine equivalent daily dose, was collected through a review of the patients’ medical records.

The CAGE‐AID questionnaire is an important tool to detect a history of alcoholism or drug use in advanced cancer patients. Patients with CAGE‐AID‐positive responses are more likely to engage in recreational drug use and thereby are at risk of rapid opioid dose escalation and abuse. Previous studies have suggested the routine use of the CAGE‐AID questionnaire should be implemented for cancer patients requiring opioids [14].

Our primary objective was to determine whether an improvement would occur in the patterns of use, storage, and disposal of opioids among cancer outpatients with implementation of a patient educational program. Unsafe storage was defined as storing medications where they are visible and/or accessible to people other than the patient and the designated caregiver. Sharing or losing opioids was defined as unsafe use.

Statistical Analysis

The patterns of storage, disposal, and usage of 300 historical controls and 300 consecutive patients who had received the EM were compared using the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. The Wilcoxon rank‐sum test was used to examine the differences among continuous variables between the patient characteristic groups.

Results

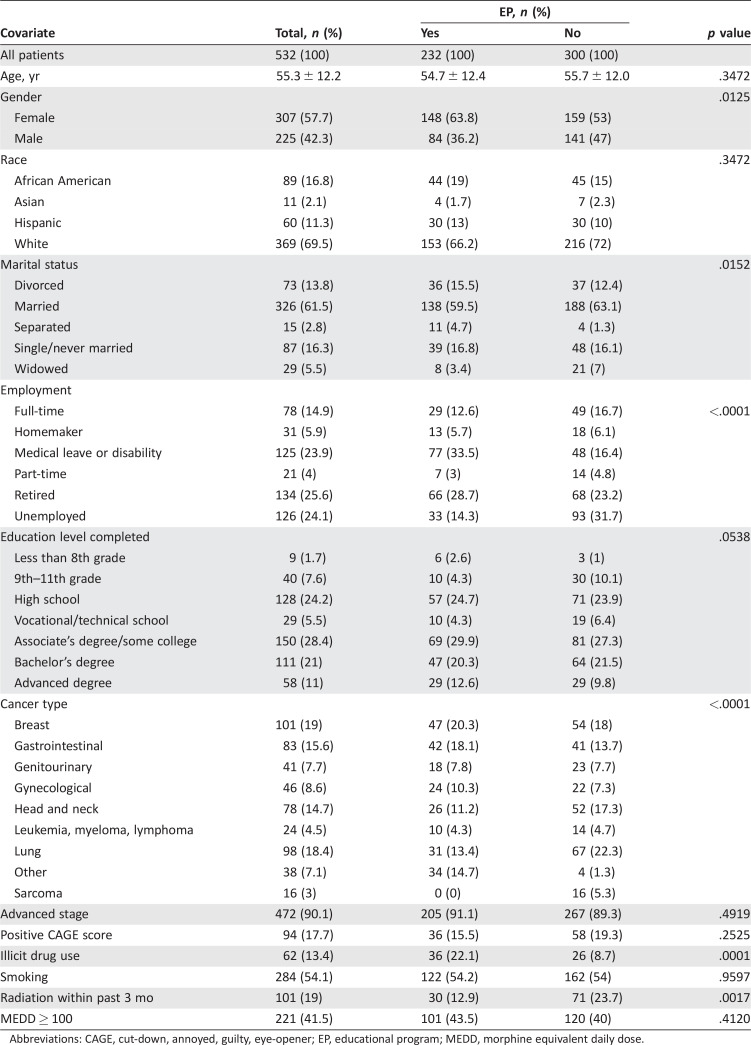

The data from a total of 300 control patients who had participated in a similar survey were compared with the data from 300 patients surveyed who had received EM from a PC staff member. The proportion of races and sexes sampled was similar to the patient population seen in other PC studies our group has conducted at MD Anderson Cancer Center [15], [16], [17]. The comparison between the two groups is presented in Table 1. It is important to note that patient characteristics (CAGE‐AID score and marital status) previously found to be predictors of unsafe opioid use, storage, or disposal in our previous study were not found to be different between the two groups, except for illicit drug use.

Table 1. Comparison of patient characteristics between groups before and after implementation of opioid educational program.

Abbreviations: CAGE, cut‐down, annoyed, guilty, eye‐opener; EP, educational program; MEDD, morphine equivalent daily dose.

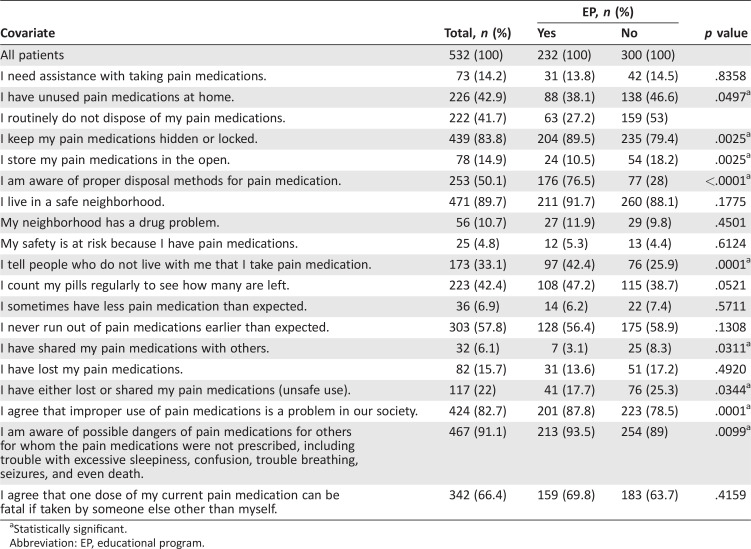

Comparisons of opioid storage and disposal are presented in Table 2. After the receipt of the educational materials, fewer patients had unused opioids at home (38.1% vs. 46.6%; p = .0497), more patients kept their opioids in a safe place (locked, 14% vs. 9.5%; hidden, 75.4% vs. 69.9%; p = .0025), and more patients were aware of the proper methods of opioid disposal (76.5% vs. 28%; p < .0001).

Table 2. Comparison of patients’ attitudes, usage, storage, and disposal of opioids between groups before and after implementation of opioid education program.

Statistically significant.

Abbreviation: EP, educational program.

A comparison of the patients’ attitudes toward opioid usage is shown in Table 2. After implementation of the educational materials, more patients never shared their opioids with someone else (96.9% vs. 91.6%; p = .0311), fewer patients reported unsafe use of opioids (17.7% vs. 25.3%; p = .0344), more patients believed that improper use of opioids is a common problem in the society (p < .0001), and more patients were aware of the danger of their opioids for others (p = .0099).

The patients who received the EM were more aware of proper opioid disposal methods (76% vs. 28%; p ≤ .0001), less likely to share their opioids with someone else (3% vs. 8%; p = .0311), and less likely to practice unsafe use of opioids (18% vs. 25%; p = .0344; Table 2). Patients who received the EM were less likely to have unused medication at home (38% vs. 47%; p = .0497) and more likely to keep their medications in a safe place (hidden, 75% vs. 70%; locked, 14% vs. 10%; p = .0025).

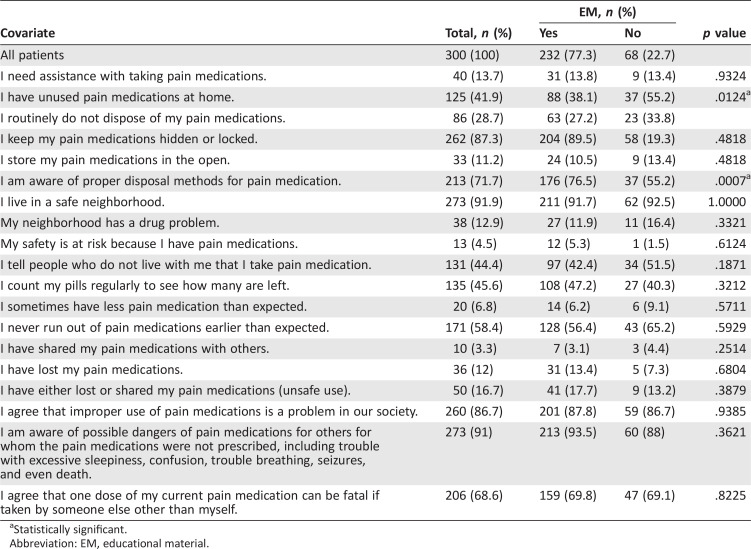

Of the 300 patients surveyed, 232 (77.3%) reported that they received the EM with their prescriptions and were designated as group 1. The 68 patients (23%) who did not recall receiving the EM were designated as group 2. The patients who recalled having received the EM were more likely to be female (148 of 232 [63.8%] vs. 33 of 68 [48.5%]; p = .0237). The comparison of the use, storage, and disposal of opioids between groups 1 and 2 is shown in Table 3. Those who did not recall receiving the EM were more likely to have unused medications at home (37 of 68 [55.2%] vs. 88 of 232 [38.1%]; p = .0124) and are less aware of proper opioid disposal (37 of 68 [55.2%] vs. 176 of 232 [76.5%]; p = .0007).

Table 3. Comparison of patients’ attitudes, usage, storage, and disposal of opioids between group that recalled receiving EM and group that did not.

Statistically significant.

Abbreviation: EM, educational material.

Of the surveyed patients, 213 of 300 reported the source of their information. Of the 213 patients, surveyed, 90 (42%) reported receiving their information regarding opioid storage, use, and disposal from the PC clinic and staff. Other sources of information reported by the surveyed patients included other health care providers (60 of 213 [28%]), family or friends (7 of 213 [3%]), and the media (58 of 213 [27%]).

Discussion

A previous study conducted by our group showed that a considerable proportion of cancer patients receiving opioid prescriptions do not store, use, and dispose of opioids in a safe manner [12]. Access to these medications poses a danger and an increased risk of drug abuse and misuse, accidental poisoning, and diversion. Following the implementation of an educational program in the PC clinic, an improvement in the knowledge and practices relating to opioid use, storage, and disposal was observed. Improvements were observed for the patients who recalled receiving the EM and those who did not. Overall improvement was seen across all three domains covered in the EM. Most patients reported that knowledge was gained from the education provided in the PC clinic.

The educational program was designed to address the inadequate knowledge regarding opioids demonstrated by our patients in a previous survey. Several studies have shown various levels of success using different modalities to improve patient education and other outcomes [18], [19], [20], [21]. Our group decided to use a pamphlet as our EM (along with personalized education by our PC clinic medical staff) because of its straightforwardness, ease of implementation, and reproducibility. These data are encouraging, as this simple intervention requires minimal time involvement by the health care professional and was successful in changing the attitudes and beliefs of patients.

It has been proposed that information might need to be presented at least six times using different modalities for better recall and understanding [22]. Repetition, through the use of both verbal (PC staff) and visual (EM pamphlet) tools, provides and strengthens the knowledge that later translates to more safe opioid practices. The message in both tools is the same, and the medical staff providing the personalized education emphasizing critical points all received the same in‐service training. The improvement in patient knowledge and practices seen in our study is similar to that of other studies, which also demonstrated success in education‐ based outcomes. A study measuring patient readiness found that the use of either face‐to‐face instruction or a written pamphlet, in addition to the usual preoperative clinic visit, was superior to a preoperative visit alone [19]. Also, improvement in sputum collection occurred with the use of a brochure [23], and the addition of a brochure to systematic nursing education for caregivers of patients with nasogastric tubes improved the ability of the caregivers to care for their patients [24].

It has been previously shown that EM in the form of pamphlets or brochures is only useful if the patient is motivated to learn and know more. The contact with the PC staff when the EM is given is a powerful act of persuasion that can encourage patients to read the EM that they would otherwise have disregarded. This would be especially true for patients who have been to the PC clinic multiple times and have built rapport and trust with the medical staff. Patients must feel invested in acquiring the additional knowledge for the EM to work. That added contact with PC staff is an opportunity to emphasize the value of that knowledge.

The EM that patients take home with them each time they receive an opioid prescription allows them to reference information at their own convenience. It is a tangible reminder of the information discussed during their clinic visit. They are also able to readily share this information with caregivers, family, and others, further reinforcing the information and knowledge.

In both patient populations, approximately one half of the patients enrolled had an educational level of at least some college or an associate's degree. This underscores the need to use simple, plain, and concise language in the EM to ensure understanding and compliance. This is especially relevant, because the EM can also serve as a starting point for discussions of patients’ concerns or could be a prompt sheet that patients can use to gather more information from medical care providers.

It is important to note that some areas still need further improvement, such as those involving storage and disposal. Despite the EM presented and the awareness of proper disposal, more than one third of our patients still had unused opioids at home for several reasons, including possible future use, which might have been a reflection of anxiety in achieving good pain control. A significantly higher proportion of patients had their opioids hidden after receiving the EM, an indication of the success of the program in improving opioid storage among patients prescribed with narcotics. This aligned with the improvement in safe opioid usage practices reported in the survey.

Interestingly, forthose patients who did not recall receiving the EM, all other safe practices relating to opioid use, storage, and disposal were the same as for those who did recall having received the EM, except for the presence of unused opioids at home and awareness of proper disposal. It is possible that the behavior of these patients was influenced by the EM, even if they did not recall receiving it. It is also possible that their behavior was modified by the education given by the PC staff. More research is needed to better understand the role of EM use in safe opioid use, storage, and disposal with these patients.

The 300 patients in the control group belonged to a previous cohort, which presents a possible limitation, because this previous control group might have acquired education on opioid use, storage, and disposal from the media or other sources that could have influenced their behavior. However, owing to the close time relationship and the same type of patient population, we believe this is not a likely explanation; however, more research is necessary to characterize the knowledge and behavior among these cancer patients receiving opioids.

Learners come in a wide spectrum, and not all concerns will be addressed by handing out a pamphlet of EM. We strongly believe that the EM in a patient's possession can be an instrument for further in‐depth discussions regarding opioid safety. Patient‐driven content of educational materials might need to be incorporated to make our EM more robust and substantial. Other modalities using new technologies such as the use of applications in mobile devices could be on the forefront.

Conclusion

Patient education can improve knowledge and modify behavior if delivered in a simple and clear manner. Universal education that is consistent and frequently communicated reduces unsafe opioid use, storage, and disposal practices in patients with advanced cancer. It is our hope that with this simple and reproducible intervention, we will be able to do our part in curbing the growing epidemic of opioid abuse. Much more needs to be done on both the clinical and research fronts. More interactive and creative methods to engage and educate patients are essential in addressing the problem with opioid abuse.

Contributed equally.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Maxine de la Cruz, Akhila Reddy, Jimin Wu, Diane Liu, Sriram Yennurajalingam, Eduardo Bruera

Provision of study material or patients: Maxine de la Cruz, Akhila Reddy, Vishidha Balankari, Margeaux Epner, Susan Frisbee‐Hume, Hilda Cantu, Eduardo Bruera

Collection and/or assembly of data: Maxine de la Cruz, Akhila Reddy, Vishidha Balankari, Margeaux Epner, Susan Frisbee‐Hume, Jimin Wu, Diane Liu, Hilda Cantu, Janet Williams

Data analysis and interpretation: Maxine de la Cruz, Akhila Reddy, Jimin Wu, Diane Liu, Sriram Yennurajalingam, Eduardo Bruera

Manuscript writing: Maxine de la Cruz, Akhila Reddy

Final approval of manuscript: Maxine de la Cruz, Akhila Reddy, Vishidha Balankari, Margeaux Epner, Susan Frisbee‐Hume, Jimin Wu, Diane Liu, Sriram Yennurajalingam, Hilda Cantu, Janet Williams, Eduardo Bruera

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1. Warner M, Chen LH, Makuc DM et al. Drug poisoning deaths in the United States, 1980‐2008. NCHS Data Brief 2011;1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bruera E, Hui D. Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1261–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Manchikanti L, Helm S II, Fellows B et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician 2012; 15(suppl):ES9–ES38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Ailinani H et al. Therapeutic use, abuse, and nonmedical use of opioids: A ten‐year perspective. Pain Physician 2010; 13:401–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dahlin CM, Kelley JM, Jackson VA et al. Early palliative care for lung cancer: Improving quality of life and increasing survival. Int J Palliat Nurs 2010;16: 420–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011; 30:454–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cohen J, Wilson DM, Thurston A et al. Access to palliative care services in hospital: A matter of being in the right hospital. Hospital charts study in a Canadian city. Palliat Med 2012;26:89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps—From the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3052–3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: Evidence‐ based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:e58–e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reddy A, Yennurajalingam S, Pulivarthi K et al. Frequency, outcome, and predictors of success within 6 weeks of an opioid rotation among outpatients with cancer receiving strong opioids. The Oncologist 2013;18:212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deandrea S, Montanari M, Moja L et al. Prevalence of undertreatment in cancer pain. A review of published literature. Ann Oncol 2008;19: 1985–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reddy A, de la Cruz M, Rodriguez EM et al. Patterns of storage, use, and disposal of opioids among cancer out patients. The Oncologist 2014;19: 780–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA 1984;252:1905–1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Parsons HA, Delgado‐Guay MO, El Osta B et al. Alcoholism screening in patients with advanced cancer: Impact on symptom burden and opioid use. J Palliat Med 2008;11:964–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yennurajalingam S, Atkinson B, Masterson J et al. The impact of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden in advanced prostate cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2012;15: 20–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yennu S, Urbauer DL, Bruera E. Factors associated with the severity and improvement off atigue in patients with advanced cancer presenting to an outpatient palliative care clinic. BMC Palliat Care 2012;11:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yennurajalingam S, Kang JH, Cheng HY et al. Characteristics of advanced cancer patients with cancer‐related fatigue enrolled in clinical trials and patients referred to outpatient palliative care clinics. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Axtell S, Haines S, Fairclough J. Effectiveness of various methods of teaching proper inhaler technique: The importance of pharmacist counseling. J Pharm Pract 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alsaffar H, Wilson L, Kamdar DP et al. Informed consent: Do information pamphlets improve postoperative risk‐recall in patients undergoing total thyroidectomy: Prospective randomized control study. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;45:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rose P, Sakai J, Argue R et al. Opioid information pamphlet increases postoperative opioid disposal rates: A before versus after quality improvement study. Can J Anaesth 2016;63:31–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mohammadi A, Mojtahedzadeh R, Emami A et al. Pamphlet as a tool for continuing medical education: Performance assessment in a randomized controlled interventional study. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2015;29:252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cameron J, Pierce WD. Rewards and Intrinsic Motivation: Resolving the Controversy. Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alisjahbana B, van Crevel R, Danusantoso H et al. Better patient instruction for sputum sampling can improve microscopic tuberculos is diagnosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2005;9:814–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chang SC, Huang CY, Lin CH et al. The effects of systematic educational interventions about nasogastric tube feeding on caregivers’ knowledge and skills and the incidence of feeding complications. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1567–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]