Abstract

Prostate cancer (PC) treatment side-effects such as erectile dysfunction (ED) can impact men’s quality of life (QoL), psychosocial and psycho-sexual adjustment. Masculinity (i.e., men’s identity or sense of themselves as being a man) may also be linked to how men respond to PC treatment and ED however the exact nature of this link is unclear. This review aims to provide a snapshot of the current state of evidence regarding ED, masculinity and psychosocial impacts after PC treatment. Three databases (Medline/PsycINFO, CINHAL, and EMBASE) were searched January 1st 1980 to January 31st 2016. Study inclusion criteria were: patients treated for PC; ED or sexual function measured; masculinity measured in quantitative studies or emerged as a theme in qualitative studies; included psychosocial or QoL outcome(s); published in English language, peer-reviewed journal articles. Fifty two articles (14 quantitative, 38 qualitative) met review criteria. Studies were predominantly cross-sectional, North American, samples of heterosexual men, with localised PC, and treated with radical prostatectomy. Results show that masculinity framed men’s responses to, and was harmed by their experience with, ED after PC treatment. In qualitative studies, men with ED consistently reported lost (no longer a man) or diminished (less of a man) masculinity, and this was linked to depression, embarrassment, decreased self-worth, and fear of being stigmatised. The correlation between ED and masculinity was similarly supported in quantitative studies. In two studies, masculinity was also a moderator of poorer QoL and mental health outcomes for PC patients with ED. In qualitative studies, masculinity underpinned how men interpreted and adjusted to their experience. Men used traditional (hegemonic) coping responses including emotional restraint, stoicism, acceptance, optimism, and humour or rationalised their experience relative to their age (ED inevitable), prolonged life (ED small price to pay), definition of sex (more than erection and penetration), other evidence of virility (already had children) or sexual prowess (sown a lot of wild oats). Limitations of studies reviewed included: poorly developed theoretical and context-specific measurement approaches; few quantitative empirical or prospective studies; moderating or mediating factors rarely assessed; heterogeneity (demographics, sexual orientation, treatment type) rarely considered. Clinicians and health practitioners can help PC patients with ED to broaden their perceptions of sexual relationships and assist them to make meaning out of their experience in ways that decrease the threat to their masculinity. The challenge going forward is to better unpack the relationship between ED and masculinity for PC patients by addressing the methodological limitations outlined so that interventions for ED that incorporate masculinity in a holistic way can be developed.

Keywords: Erectile dysfunction (ED), masculinity, prostate cancer (PC), psychosocial, quality of life (QoL)

Introduction

Globally, over one million new cases of prostate cancer (PC) were diagnosed in 2012 with incidence expected to increase to 1.7 million cases in 2030 (1,2). PC incidence is highest in western countries such as Australia/New Zealand, North America, and Europe (age standardised incidence rates per 100,000 range from 85.0 to 111.6) (1,2). Parallel to increasing incidence, survival has also increased in the UK, North America and Australia/New Zealand such that approximately 90% of men now survive their PC 5 or more years and over 80% survive at least 10 years (3-5). Although promising, extended survival means that many men live with high and enduring treatment side-effects that can persist for a decade or more (6,7). For instance, treatments such as surgery, radiation therapy, and androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) can have negative effects on urinary, bowel, hormonal, or sexual function (8,9). Regarding the latter, erectile dysfunction (ED) is the most common impact on sexual function and is often accompanied by a loss of sexual desire or difficulty reaching orgasm (10).

The exact incidence of ED following PC therapy is unknown with most epidemiological data derived from the post-radical prostatectomy (RP) cohort. While the exact recovery of erectile function is difficult to compare when reviewing clinical studies due to variables such as the definition of ED, the definition of return of erectile function, the use of erectogenic medication and the use of multimodal PC therapy, it is widely accepted that post-RP ED occurs for around 60–70% of men (11-15) despite advances in surgical techniques and technology. Factors such as the age of the patient, the level of pre-treatment erectile function, the extent of surgical neurovascular preservation, intraoperative changes on erectile haemodynamics, stage of disease and body mass index can contribute to the erectile outcome (13,15,16). In contrast to post-RP ED, radiation-induced ED usually develops later (usually 3-year post-radiation) with the actual rates of ED between RP and radiation groups similar (17). Several pathophysiological mechanisms for ED have been proposed that include cavernous nerve injury, vascular compromise (e.g., accessory pudendal artery ligation), damage to nearby structures, local inflammatory changes relating to surgical and radiation effects, cavernosal smooth muscle hypoxia with ensuing smooth muscle apoptosis and fibrosis, as well as corporal veno-occlusive dysfunction causing venous leakage (11-15).

In addition to physical treatment side-effects, for some men ED has quality of life (QoL) and psychosocial impacts including but not limited to depression, cancer-specific distress, self-esteem, relationship satisfaction, coping and adjustment (18-21). Masculinity (i.e., men’s identity or sense of themselves as being a man) may also be linked to how men respond to PC diagnosis and treatment including their experience of psychological and psychosexual distress and adjustment (22-28). Low masculine self-esteem has been shown to contribute to increased anxiety, depression and cancer-specific distress in men with PC (29). Masculinity has also been implicated in men’s reluctance to seek help for their emotional or sexual concerns after PC treatment (24,30,31). However, the exact nature of the impact of ED on psychosocial aspects of men’s experience after PC treatment and how masculinity may feed into this is unclear (20,32).

Thus, the aim of this review is to provide a snapshot of the current state of the evidence regarding ED, masculinity and psychosocial impacts after PC treatment. Our review considers three questions:

How is masculinity described in the literature in relation to ED after PC treatment?

Does masculinity moderate the effects of ED on men’s psychosocial or QoL outcomes after PC treatment?

Is masculinity considered as a state of being that is affected by ED (i.e., masculinity is an outcome) after PC treatment?

Methods

Search strategy

The search strategy occurred in a two-step process. First, Medline and PsycINFO [via Ovid), CINAHL, and EMBASE databases were searched (January 1st, 1980 to January 31st, 2016] using the following keywords:

(“prostat$ cancer” OR “prostat$ neoplasm$” OR “prostat$ carcinoma”);

(masculine OR masculinity OR masculinities OR manhood OR man-hood OR “sex role” OR “sex-role” OR “male identity” OR “male identities” OR “gender identity” OR “gender identities” OR “sexual identity” OR “sexual identities”);

1 AND 2;

3 limit to Human AND English.

Second, targeted searches on Google Scholar were conducted with the terms “prostate cancer” AND (masculinity OR masculine OR hegemonic). Duplicates were removed prior to examining article titles and abstracts. Cited reference searches of articles which met final inclusion criteria for review were conducted on Web of Science, Google Scholar, and via hand searches of article reference lists. For retrieval and eligibility of articles and data extraction, one author and a research assistant independently completed each stage and consulted with a third independent reviewer to resolve differences in decision-making.

Eligibility criteria

Potential articles were identified initially by examining the title and abstract and were then retrieved for more detailed evaluation against the apriori inclusion criteria. Peer-reviewed quantitative or qualitative journal articles containing primary data were included if they met the pre-determined eligibility criteria below:

Participants were men (or a sub-group of men) who had been diagnosed with and received treatment for any stage of PC;

Included a measure of ED or sexual function/dysfunction;

Included a measure of masculinity in quantitative studies or masculinity emerged as a key theme in qualitative studies;

Included masculinity or psychosocial (e.g., distress, social support, adjustment) or QoL outcome(s);

Published in English language;

Published after January 1st, 1980 and prior to January 31st, 2016.

Reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, commentaries, books or book chapters, guidelines, position statements, conference proceedings, abstracts and dissertations were excluded.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was created prior to the review to identify key characteristics of studies which met criteria for inclusion: source (author, year and country of publication); study design; participants (age, sexual orientation, disease stage, treatment type, time since treatment, ED score); masculinity measure; results corresponding to masculinity outcomes and masculinity as a contributor to (correlate) or moderator of psychosocial or QoL outcomes. Characteristics of included studies are summarised in Tables S1,S2.

Results

Search results

Systematic search

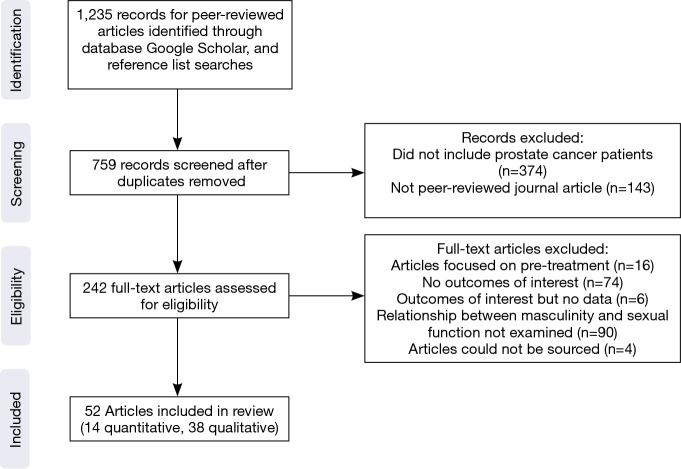

The systematic search identified 759 records for review after duplicates were removed. Of these, 242 underwent full-text review. One hundred and ninety articles were excluded because they focused on pre-treatment decision-making, had no outcomes of interest, or the relationship between masculinity and sexual function was not examined (Figure 1). The remaining 52 articles were reviewed and these included 14 quantitative and 38 qualitative studies. Quantitative research comprised 7 studies that were cross-sectional, 5 prospective, and 2 randomised controlled trials (RCT). Qualitative research included 35 cross-sectional and 3 prospective studies. Studies were published from 1995 to 2016 and most were conducted in the USA (39%), Australia (23%), Canada (14%), Europe (10%), or the UK (8%).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of systematic review inclusion and exclusion process

Sample characteristics

Sample sizes ranged from 3 to 1,070 (median =20); 68% of studies had less than 50 participants. Twenty-four studies provided a mean age for men and this ranged from 57.0 to 76.2 years. Most studies did not report the sexual orientation of the sample (65%) and where this did occur almost all sampled exclusively heterosexual men (33%); only one study focused on the experience of homosexual men (33). Of the 26 studies reporting disease stage, most men had localised PC (69%) and were treated with RP (45% of studies included mostly men receiving RP, 23% radiation therapy, and 23% hormonal ablation therapy; 9% of studies did not report treatment type). Less than half (45%) of studies reviewed reported time since treatment and this ranged from 0 to 60 months. Nine studies (17%) reported ED scores from validated measures and of these most used the sexual function subscale from the Expanded Prostate cancer Index Composite.

Masculinity measures

Measures most often used to assess masculinity in quantitative studies were the masculine self-esteem scale (33-36), Bem Sex-Role Inventory (37,38), or the single item EORTC-QLQ-PR25 measure (‘Have you felt less masculine as a result of your illness or treatment?’) (39,40). Other measures used in a single study were the Sexual Self-Schema scale for Men (41), the Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory (22), Cancer-related Masculine Threat scale (23), and the Masculinity in Chronic Disease Inventory (32). Two studies used un-validated measures (38,42).

Masculinity and sexual function after PC treatment

PC treatment and subsequent ED, loss of libido, and/or potency was consistently described in qualitative studies as having an impact on, or being a threat to, men’s sense of masculinity (43-50). Some men chose to undergo radiation therapy instead of RP because the former offered a better chance of preserving sexual function which in their view was equivalent to masculinity (51,52). In almost every study, the belief that masculinity was lost (‘no longer a man’) or somehow diminished (‘not a whole man’) was described (26,43,44,48,52-71), and this was a source of anxiety, depression, or embarrassment for men; made them question their self-worth; and created feelings of disempowerment and a fear that they may be stigmatised (27,43-46,49,60,61,70,72-74).

Other qualitative studies described masculinity as framing men’s experiences and adjustment after PC treatment (54). In this regard, due to their sexual dysfunction some men believed that they could no longer live a normal life (63) or respond appropriately in everyday interactions with women (72,73). Men also discussed the possibility that their wives would leave them because they could not satisfy them sexually or be an ‘active partner’ (66,70,75). Men limited social activities which had the potential for sex (e.g., parties) (61,67); adopted strategies that maintained the macho façade such as pseudo courtship or laughing at jokes about ED (66,67); or used traditional (hegemonic) masculine coping responses such as emotional restraint (60), stoicism (60,76), acceptance (66,76), optimism (27,67,69), and humour (47).

Many qualitative studies discussed that men rationalised their ED or sexual dysfunction through active attempts to cognitively reframe their experience which in turn allowed them to preserve their sexual identity or sense of masculinity. Men did this in four main ways: used age as a reference point to normalise or accept their experience (ED is an inevitable consequence of aging, ED is worse for younger men) (26,28,43-46,54,60,61,63,66,67,70); viewed ED or sexual dysfunction as a trade-off for prolonged life or health (health more important, small price to pay for being alive) (26,27,43,47,58,60,63,65-67,77); broadened their definition of sex as encompassing more than an erection and penetration (e.g., hugging, kissing, conversation and company) (27,44-46,60,61,63,66,67,75); and looked for other evidence of masculinity (e.g., already had children, sowed a lot of wild oats, being grateful for prior sexual experiences) (27,60,66).

In contrast to the majority of qualitative work, a small number of studies which sampled older men reported that changes in men’s sexual function had minimal impact on masculinity (28,44-46,76). The potential impact of ED on masculinity was also discussed in studies sampling men from a range of ages as something that happened to other men (43,63); ED was viewed as an ill-effect that men could live with (44-46); or ED had minimal impact because men or their partners had already experienced sexual dysfunction due to chronic or co-morbid disease (66,75).

Masculinity as a moderator

Two quantitative studies examined masculinity as a moderator of the relationship between sexual function and psychosocial or QoL outcomes. Together these studies showed that when men who had poor sexual functioning endorsed more traditional (hegemonic) masculine values they had worse social functioning, role functioning, and mental health outcomes (22), including depression (41).

Masculinity as an outcome or correlate

In the remaining 12 quantitative studies, masculinity was described as an outcome (32-36,38-40,42,78), or as a potential correlate or predictor of sexual function or bother (23,36,37,42). Collectively, these studies showed a consistent correlational relationship between poor sexual function and decreased masculinity (32,34-36,39,40,42,78), or increased masculinity and poorer sexual outcomes (23,36,42). However, this relationship did not hold in two studies when sexual function was included with other variables in a multivariate model as predictors of masculinity (33) or when the impact of masculinity on sexual symptoms at different points on the treatment trajectory were considered (37).

Of these quantitative studies, two also described the conditions under which the relationship between sexual function and masculinity may be strengthened (moderated) by interpersonal variables (36,38). Specifically, men who had sexual dysfunction or bother were more likely to interpret this as a threat to their masculinity if they had higher interpersonal sensitivity which can diminish social support and communication (38), or their spouse perceived low marital affection (36).

Discussion

Based on this review it is clear that for most men masculinity is crucial in their experience of PC treatment and ED in two ways: masculinity frames how men interpret what is happening to them; and men’s sense of themselves and their masculinity suffers harm. While there is evidence that some men manage to cope with this impact and are able to cognitively reframe their experience relative to aging, prolonged life, the definition of sex, and other evidence of their virility or sexual prowess, this is a task that for many men will be challenging. Therefore, the role of clinicians and health practitioners in the field is to help men and their partners broaden their perceptions of sexual relationships and also to facilitate adjustment by assisting men to make meaning of, or seek alternative meaning for, their experience that presents less of a threat to their masculine identity.

While the proliferation of qualitative research in this context offers some key insights, this work has focused on understanding the masculinity phenomena. There are few quantitative studies and of these most confirm a correlational relationship between ED and masculinity and, with few exceptions, do not extend beyond this. Moving forward, three areas of focus for future research are apparent. First, we need empirical studies that establish the role of masculinity as a mediator or moderator of psychosocial and QoL outcomes for men experiencing sexual dysfunction. Two studies in this review (22,41) suggest a moderation effect for masculinity; men who had ED and more strongly endorsed traditional masculine values experienced poorer QoL and mental health outcomes. However, recent work on men’s decisions to seek medical help for their sexual concerns after PC treatment suggests that aspects of masculinity such as emotional self-reliance and placing high value on the importance of sex may be a strength for men to draw upon in promoting help-seeking and ultimately better adjustment (30). The conditions under which masculinity may be a help or a hindrance to PC patient’s adjustment require further exploration.

Second, for men experiencing ED after PC treatment, empirical studies are needed to identify factors that may interact with masculinity with regards to its influence on QoL or psychosocial outcomes, and determine their relative importance. Two studies in this review (36,38) reported that interpersonal factors such as marital affection may moderate the extent to which men interpret ED as a threat to their masculinity. However, there are a range of individual (e.g., age, sexual orientation), psychological (e.g., depression, anxiety, pre-treatment expectations), social (e.g., nature and quality of relationships, support) and medical (e.g., co-morbidities, medication use, pre-treatment erectile function, other treatment side-effects, treatment type) factors that may also be important and these have yet to be explored fully.

Third, to facilitate knowledge advancement about the role and contribution of masculinity, established theory and consistent measurement approaches should be adopted. This review noted a trend toward use of masculinity measures that reflect traditional, hegemonic masculine values and ideals (e.g., Bem Sex Role Inventory, Conformity to Masculine Norms Inventory, Sexual Self-Schema scale for Men) that are not contextualised for men with cancer. Where context-specific scales have been applied, they are ambiguous, single-item measures (e.g., EORTC-QLQ-PR25 question) or capture only one aspect of masculinity (e.g., Masculine Self-Esteem scale). Recent development of two context-specific masculinity scales, the Cancer-related Masculine Threat scale (23) and the Masculinity in Chronic Disease Inventory (32) show promise, however more research is needed to establish the utility of these scales across the diversity of men who have ED after PC treatment, particularly accounting for sexual orientation, ethnic background, and treatment type.

Given the role of masculinity as an influencer of men’s response to ED after PC treatment, our challenge going forward is to develop interventions that are responsive to masculinity, optimally working with masculinity as a potential strength. To do this we need to better unpack masculinity as it relates to ED and PC treatment through context-specific measurement of masculinity; quantitative empirical, prospective studies that consider the experience of men with differing sexual orientations, socio-demographic backgrounds, and PC treatments; assess moderating and mediating factors; and test interventions for ED that incorporate masculinity in a holistic way. In the interim, it is important for clinicians to invite a conversation with men and their partners about their expectations and goals with regards to sexual outcomes after a PC diagnosis and treatment and implement a care plan matched to these. In addition, given the links between a man’s sexual QoL and his psychological outcomes, this care plan needs to also address psychosocial and subjective well-being based on current best practice approaches (79).

Acknowledgements

SK Chambers is supported by an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship. Acknowledgement to Lisa Nielsen, Liz Eldridge and Kirstyn Laurie for research assistance.

Table S1. Quantitative results summary (n=14).

| Source & design | Participants | Masculinity measure | Masculinity as an outcome, mediator, moderator or correlate | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allensworth-Davies [2016] (33), USA; CX | 111 men recruited 2010–2011; | Masculine self-esteem scale (Clark) | Outcome | • Better sexual function was significantly correlated with increased masculine self-esteem (Spearman’s rho =0.22, P=0.02), however, when included in a multivariate model sexual function was not a significant predictor of masculine self-esteem, B=0.09; CI, 0.07–0.24; P=0.26 |

| Age: >50 years; | ||||

| SO: homosexual; | ||||

| Cancer stage: localised; | ||||

| Tx type: 60% RP, 27% RT (14% EBR, 13% Br), 9% WW; | ||||

| Time since Tx: ≥12 months prior to study; | ||||

| Sexual function (EPIC): mean ± SD, 36.6±20.6 | ||||

| Burns [2008] (22), USA; CX | 234 men; | Conformity to masculine norms inventory (Mahalik) | Moderator | • Men with poor sexual function had poorer social functioning, role functioning, and mental health, when they more strongly endorsed traditional masculine norms |

| Age: mean ± SD, 62.4±8.7 years; | ||||

| SO: 90% heterosexual, 5% homosexual, 4% bisexual, 1% transgender; | ||||

| Cancer stage: 76% localised, 24% advanced; | ||||

| Tx type: 48% RT (26% EBR, 22% Br), 41% RP, 38% HA, 5% cryosurgery, 3% chemo; | ||||

| Time since tx: mean ± SD, 28.2±32.4 months; | ||||

| Sexual function (EPIC): mean ± SD, 39.9±33.0 | ||||

| Chambers [2015] (53), Australia; CX | 403 men; | Masculinity in chronic disease inventory (Chambers) | Outcome | • Men who had severe ED reported lower scores on the masculinity measure compared to men who had moderate to mild ED (mean, IIED =3.68 vs. 4.00), F(1,187) =9.85, P=0.002 |

| Age: mean ± SD, 70.3±7.3 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: NR; | ||||

| Tx type: 61% RP, 43% RT, 27% HA, 6% AS or WW; | ||||

| Time since tx: NR; | ||||

| Sexual function (IIED): mean ± SD, 7.2±9.2 | ||||

| Clark* [1997] (34), USA; CX | 410 men; | Masculine image | Outcome | • Increased sexual problems were associated with a decreased masculine image (r=−0.41) |

| Age: range, 45–93 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: advanced; | ||||

| Tx type: HA (chemical or orchiectomy); | ||||

| Time since tx: 44% ≤1 year, 38% 2–3 years, 18% 4–5 years; | ||||

| Sexual function: NR | ||||

| Clark, Inui [2003] (35), USA; CX | 349 men; | Masculine self-esteem scale (Clark) | Outcome | • Increased sexual dysfunction was significantly associated with decreased masculine self-esteem (β=−0.17, P=0.003) |

| Age: >50 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: localised; | ||||

| Tx type: 44% RT (39% EBR, 5% Br), 39% RP, 9% AS or WW, 8% HA; | ||||

| Time since tx: 12–48 months; | ||||

| Sexual function: NR | ||||

| Davison [2007] (39), Canada; PR | 130 men; | EORTC-PC module question (Have you felt less masculine as a result of your illness or treatment?) | Outcome | • Scores pre-post RP showed decreased sexual function after tx and significantly more men felt less masculine after tx (1.32±0.66 vs. 1.77±0.80, P<0.001) |

| Age: mean ± SD, 62.1±6.0 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: localised; | ||||

| Tx type: 100% RP, 30% HA; 94% had no additional tx after 1 year; | ||||

| Time since tx: 12 months; | ||||

| Sexual function (SHIM): 90% had mild-moderate, moderate, or severe ED 1 year post-RP | ||||

| Galbraith [2001] (37), USA; PR | 185 men; | Bem sex-role inventory-short form (Bem) | Correlate | • Masculinity was not correlated with sexual symptoms at 6, 12, or 18 months post-tx |

| Age: mean, 68.0 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: localised; | ||||

| Tx type: 68% RT (25% mixed-beam RT, 14% conventional RT, 13% proton-beam RT), 32% RP, 16% WW; | ||||

| Time since tx: NR; | ||||

| Sexual function: NR | ||||

| Hoyt [2013, 2015] (23,41), USA; PR | 66 men; | Cancer-related masculine threat; sexual self-schema scale for men (Anderson) | Correlate, moderator | • Increased cancer-related masculine threat (men believed cancer was inconsistent with their masculinity) predicted declines (T1 to T3) in sexual function, β=−0.17, P<0.05; • For men with higher sexual self-schema (more traditional concepts of masculinity), poorer sexual functioning was associated with increased depression, β=−0.21, P<0.05 |

| Age: mean ± SD, 65.8±9.0 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: localised; | ||||

| Tx type: 71% RP, 32% RT, HA 9%; | ||||

| Time since tx: ≤24 months (mean ± SD, 18.0±10.0); | ||||

| Sexual function (EPIC-S): mean ± SD, 41.5±28.2; | ||||

| Lucas [1995] (78), South Africa; PR | 15 men interviewed pre- and post-tx; | Bem sex-role inventory (Bem) | Outcome | • 55% of men who were sexually active pre-tx found their loss of sexual function disturbing and this was more apparent for men who had higher scores on the masculinity scale (trend only, not analysed statistically) |

| Age: mean, 76.2 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: advanced; | ||||

| Tx type: HA (orchiectomy); | ||||

| Time since tx: 3 months; | ||||

| Sexual function: all men reported loss of sexual function post-tx | ||||

| Molton [2008] (38), USA; RCT | 101 men (60 intervention, 41 control); | Concern about sexual functioning (e.g., it is important for me to fulfil my sexual role as a man) | Outcome | • Men who had higher interpersonal sensitivity (moderator) were more likely to interpret sexual dysfunction as a threat to their masculine identity, and these men benefited most from the cognitive-behavioural stress management intervention (larger pre-post change in sexual function compared to controls) |

| Age: mean ± SD, intervention 60.6±4.8 years; control 59.9±5.6 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: localised; | ||||

| Tx type: RP; | ||||

| Time since tx: mean ± SD, intervention 9.4±5.3 months; control 10.7±4.9 months; | ||||

| Sexual function (EPIC): mean ± SD, intervention 26.1±22.5; control 19.2±15.6 | ||||

| O’Shaughnessy* [2013] (42), Multi-country; CX | 115 men; | Feel less of a man? Cancer impacted masculinity? | Correlate, outcome | • 20% self-reported feeling less of a man post-tx; 42% felt that cancer impacted their sense of masculinity; • The belief that cancer impacted masculinity was a significant predictor of ED (B=1.47; CI, 1.14–1.89; P=0.001) and feeling less of a man (B=13.85; CI, 3.44–55.81; P=0.001) |

| Age: 65% >60 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: localised; | ||||

| Tx type: 55% RP, 32% RT, 13% WW, 13% HA; | ||||

| Time since tx: 75% >3 months; | ||||

| Sexual function: 65% self-reported ED | ||||

| Sharpley [2014] (40), Australia, New Zealand; RCT | 1,070 men; | EORTC-QLQ-PR25 1-item (Have you felt less masculine as a result of your treatment?) | Outcome | • Increased sexual problems were correlated with loss of masculinity in the first 18 months after tx; increased sexual problems made the second largest contribution to loss of masculinity (after depression and anxiety), B=0.14, t=4.16, P<0.001; • In the first 18 months post tx, the combination of increased depression-anxiety and increased sexual problems were significant predictors of loss of masculinity P<0.001 |

| Age: mean ± SD, 67.5±6.9 years; | ||||

| SO: NR; | ||||

| Cancer stage: locally advanced; | ||||

| Tx type: 100% HA (ADT), 100% RT; | ||||

| Time since tx: NR; | ||||

| Sexual function: NR | ||||

| Zaider [2012] (36), USA; CX | 75 men; | Masculine self-esteem scale (Clark) | Outcome | • Post-tx approximately 30% of men self-reported a loss of masculinity; • Sexual bother (r=−0.68, P<0.01) and erectile functioning (r=0.37, P<0.01) were significantly correlated with loss of masculine identity; • After controlling for sexual function, loss of masculinity was a significant predictor of sexual bother (β=−0.63, P<0.001); • Loss of masculine identity was more strongly related to sexual bother if a man’s spouse perceived low marital affection |

| Age: mean ± SD, 60.6±8.2 years; | ||||

| SO: 97% heterosexual, 3% homosexual; | ||||

| Cancer stage: localised; | ||||

| Tx type: 57% RP, 32% RT; | ||||

| Time since tx: NR; | ||||

| Sexual function (IIED): mean ± SD, 14.4±11.08; 65% had poor erectile function |

*, quantitative and qualitative study. ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; AS, active surveillance; Br, brachytherapy; CT, clinical trial; CX, cross-sectional; EBR, external beam radiation therapy; ED, erectile dysfunction; EPIC, expanded prostate cancer index composite; EPIC-S, expanded prostate cancer index composite-sexual functioning; HA, hormonal ablation (including ADT, Orchiectomy); NR, not reported; IIED, international index of erectile dysfunction; PC, prostate cancer; PR, prospective; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiation therapy (including Br, EBR); SHIM, sexual health inventory for men; SO, sexual orientation; Tx, treatment; WW, watchful waiting.

Table S2. Qualitative results summary (n=38).

| Source & design | Participants | Masculinity measure | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appleton [2015] (43), UK; CX | 27 men recruited pre- or post-tx; | NR | • Physical outcomes of PC and tx impacted sense of masculinity (‘lost a bit of your manhood’, ‘not feeling like a man anymore’) but this impact was minimized with the view that health was more important, as an issue experienced by men other than the participant, as an inevitable consequence of aging, or as something that required acceptance because it was out of men’s control |

| Age: range, 57–76 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: RT (EBRT combined with HA or RP); | |||

| Time since tx: 9 pre-tx, 8 6–8 months, post-tx, 10 12–18 months post-tx; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Arrington [2003, 2010, 2015] (44-46), USA; CX | 16 men recruited from a Man-to-Man PC support group; | Do PC survivors’ stories reveal changes in their sexual identity or practice? | • ED and loss of potency presented a threat to masculinity (e.g., less of a man) and this was a source of anxiety for the men who feared being stigmatised. Men responded to this threat by devaluing sex as less important (e.g., ‘at this point in my life that wasn’t terribly important’), ED as not having a big impact (e.g., ‘an ill effect…and I can live with that’), or redefining sex as more than an erection (e.g., hugging, kissing, ‘carrying on’); • Some men believed sex was not natural and inauthentic with sexual aids and rejected their use (e.g., not wanting to be an ‘artificial man’) |

| Age: range, 66–81 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 69% RT, 19% RP and HA (orchiectomy), 13% WW; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Arrington [2008] (51), USA; CX | Observed monthly meetings of a Man-to-Man PC support group from Jan 1997 to Feb 2001; | NR | • PC deprived men of their sexual identity and some men tried a range of options to preserve their sexual function (e.g., vacuum device, injections, Viagra); • Men chose tx options that maintained their sexual ability and identity (e.g., RT in place of a RP to preserve sexual function as much as possible) |

| Age: NR; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: NR; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Berterö [2001] (54), Sweden; CX | 10 men diagnosed with PC during 1990–1995 and interviewed Aug to Dec 1997; | NR | • Men’s view of their manliness (subtheme: image of manliness) impacted their sexual life and experiences after PC tx (main theme: altered sexual patterns); • Men also drew from experiences central to men’s identities as benchmarks to help them adjust to an altered sex life [e.g., it would be worse if they were younger ‘out hunting’ for partners; or ‘waiting for the starting signal’ to start a family (procreation)]; • Tx did not only impact men physically (ED) but also their identity as if their ‘manliness has disappeared’ or was altered (e.g., ‘castrated tomcat’) |

| Age: mean, 67.6 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 70% RP, 40% HA, 40% RT and/or chemo, 10% WW; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Bokhour [2001] (72); Clark, Bokhour [2003] (73), USA; CX | 48 men recruited for interview beginning in September 1999; | NR | • Men felt that a central part of their lives as men was missing because they were no longer ‘fazed’ (aroused) by attractive women and felt that they would be ‘unable to pull it off’ (perform sexually) if they had the opportunity. For one man this impacted his sense of self-worth (being unwanted by women); • In response to ED, men described a diminished sense of masculine self-esteem (‘losing the feeling that you’re a whole man’) and this was expressed as an absence of the ‘sexual element’ in daily interactions, fear about initiating intimacy with women, or discomfort having conversations about sex |

| Age: range, 50–79 years; | |||

| SO: heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: localised; | |||

| Tx type: 98% RP or RT; 2% WW; | |||

| Time since tx: range, 12–24 months; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Broom [2004] (52) Australia; CX | 33 men; | NR | • Loss of potency post-tx was linked to masculinity (e.g., ‘so much part of the male psyche’) and was a significant concern for most men in the study; • Removal of the prostate was also discussed as making a man ‘no longer a complete man’; • Masculinity was a central aspect of decision making with some men focused on having the tx that allowed them to ‘be a man’ and retain sexual functioning rather than the most optimal life-preserving tx (e.g., choosing not to undergo RP) |

| Age: range, 40–84 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 46% RP, 36% RT (30% EBR, 6% Br), 24% HA, 6% WW, 6% none, 3% cryosurgery; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Chambers [2015] (32), Australia; CX | 15 men; | NR | • Men discussed the impact of prostate cancer on their sexuality and how much not being able to have sex (ED) impacted their masculinity (‘being a man’, ‘what blokes do’), and was akin to ‘chopping their legs off’ or ‘not being able to run’ (something that occurs naturally and is enjoyable) and this impact made some men feel inadequate |

| Age: ≥41 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 80% RP, 13% RT (EBR), 13% AS, 7% HA, 7% WW; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Chapple [2002] (26), UK; CX | 52 men interviewed during 2000–2001; | Once masculinity spontaneously emerged as a theme, men were asked to comment on whether or not their experience had affected their image of themselves as men | • Men who had tx without hormone therapy had ED but felt any impact on their masculinity was a ‘small price to pay’ for being alive or that their masculinity was a secondary concern to their health; • Some men who had hormone therapy rationalized any impact of tx on their sexual function as something that mattered less given their advancing age (but might matter more to a younger man). Another man described his sex life as disastrous and as having ‘hermaphrodite status’ |

| Age: range, 50–85 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 67% HA, 49% RT (39% EBR, 10% Br), 14% RP, 8% WW, 6% cryosurgery, 4% vaccine trial/antigen therapy, 2% chemo; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| de Moraes Lopes [2012] (55), Brazil; CX | 10 men; | NR | • Men with UI and ED felt that this impacted their masculinity which contributed to feelings of losing self-respect and esteem |

| Age: range, 48–74 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: RP; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Dieperink [2013] (56), Denmark; CX | 13 men; | NR | • Bodily changes and sexual dysfunction impacted masculinity (‘don’t feel like men anymore’) |

| Age: mean, 71.0 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: Localised or locally advanced; | |||

| Tx type: RT with HA (ADT); | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Ervik [2010] (57), Norway; CX | 10 men; | NR | • Men described hormone therapy as having a negative impact on their masculinity (‘manhood dried’, not ‘being a first lover’) |

| Age: range, 59–83 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: Localised or locally advanced; | |||

| Tx type: 70% HA; 30% AS; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function NR | |||

| Ervik [2012] (58), Norway; CX | 10 men; | NR | • Men described ED, loss of libido and impotency as impacting on their sense of masculinity (‘not a man anymore’, ‘manhood dried’); • Some men described ED as the ‘price to pay’ for prolonged life |

| Age: range, 56–83 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: 30% localised, 70% locally advanced; | |||

| Tx type: 100% HA, 20% RT; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Evans [2005] (59), Canada; CX | 57 participants including 3 men with PC; | NR | • Men with PC discussed ED as diminishing their sense of masculinity (‘sense of loss due to impotence’, ‘don’t feel whole’, ‘not the norm’) |

| Age: NR; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: NR; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Fergus [2002] (60), Canada; PR | 18 men; | NR | • Loss of sexual function posed a threat to men’s masculine identities (‘threaten a man’s sex life, you threaten the man’, not a ‘whole man’ anymore) and this was reflected in the main overarching theme: ‘Preservation of Manhood’; • Men viewed tx as a tradeoff between sex and life and sexual dysfunction was the price to pay; • Men diminished their sense of lost masculinity due to sexual dysfunction by focusing on evidence of their virility such as having children (e.g., not feeling like less of a man because they ‘biologically contributed’ to creating children). Other men focused on the fact that they still had their libido without which they believed they ‘wouldn’t be a man’; • Some men with sexual dysfunction felt inferior (not ‘measuring up’) to other men, particularly gay men who compared themselves to their partners. For these men ED made them feel not only a ‘lesser male’ but a ‘lesser gay’ male; • Some men expressed their loss of sexual ability as losing their empowerment, their image of themselves, their bragging rights about sexual prowess, and in this sense they believed they were ‘no longer a viable man’ (‘eunuch’, ‘gelding’); • Sexual dysfunction was viewed as an invisible stigma which diminished men’s self-esteem and confidence and made them feel like a ‘lesser person’ even though they still ‘looked like a man’; • Men rationalized their loss using coping approaches typically conceptualized in traditional hegemonic masculinity such as ‘carrying on’, ‘not feeling sorry for themselves’; conceding that sexual dysfunction is part of aging and would be harder to deal with if they were younger men; reconceptualising their definition of sex to include other acts of intimacy; and shifting focus to prior sexual experiences for which they were grateful |

| Age: mean, 65.0 years; | |||

| SO: 78% heterosexual, 22% homosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 61% RP, 33% RT, 22% HA, 5% WW. | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: 72% self-reported minimal to no erectile function following tx | |||

| Gannon [2010] (61), UK; CX | 7 men; | NR | • Erectile function for penetrative sex was synonymous with masculinity and ED therefore deprived men of their sexual purpose as the ‘active’ partner (e.g., ‘very important to me…as a man’, ‘being a man means that sexually you must be active’); • ED was seen by some men as embarrassing and made them feel inadequate and not the same man they used to be and this in turn limited social activities which included the potential for sex (e.g., parties); • Some men redefined masculinity to encompass the ability to give pleasure to a woman rather than just penetrative sex and this enabled them to retain their masculinity despite experiencing ED (‘I don’t feel any less of a man’); • Men also minimized the importance of sexual activity in the face of advancing age (‘I’m not a teenage boy you know’, erectile function ‘tends to drop off anyway’) |

| Age: range, 58–70 years; | |||

| SO: heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: localised; | |||

| Tx type: RP; | |||

| Time since tx: 7–15 months; | |||

| Sexual function: all men had self-reported none to minimal erectile function | |||

| Gilbert [2013] (62) Australia; CX | 44 cancer patients (26.5% PC); | Interview topic: changes to sexuality and intimacy | • Loss of sexual performance impacted masculinity and was viewed as an ‘assault on your masculinity’, with men not able to return to their ‘full self’’ after tx |

| Age: NR; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: NR; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Gray [2002] (75), Canada; CX | 3 men; | NR | • One man believed that his inability to meet his wife’s sexual needs impacted his sense of masculinity whereas the other two men conceptualized sexuality more broadly and denied that a loss of sexual function impacted their sense of masculinity (and this may also be influenced by one man’s personal experience of caring for his wife with chronic illness) |

| Age: ≥50 years; | |||

| SO: Heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 67% HA, 33% RP, 33% RT; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Hagen [2007] (47), Canada; CX | 15 men; | Participants encouraged to expand on ways they felt PC had changed how they viewed themselves as men and life in general | • ‘Threats to masculinity’ was a main theme as part of men’s adjustment to day to day living with PC and sexual dysfunction as a tx side-effect; • Men’s strategies to adjust to the impact of sexual dysfunction on their masculine identity included humour (e.g., ‘mourning a dead rooster’) or a pragmatic approach in which life with ED was preferable to no life |

| Age: mean, 63.7 years; | |||

| SO: heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 67% surgery (including RP), 27% RT, 13% HA; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Hamilton [2015] (63), Australia; CX | 18 men; | NR | • Tx side-effects including ED impacted masculinity and this in turn led to feelings of worthlessness for some men (e.g., without an erection ‘can’t have a normal life’, is life ‘really worth living?’); • Men minimized the impact of ED by rationalizing that it ‘goes with the territory’ of aging and refocused their desire on ‘conversation and company’ rather than having sex with women (e.g., ‘not so much trying to be Tom Cruise’); adopting a pragmatic view that life was more important than being able to have sex and dying prematurely; or distanced themselves as apart from traditional masculine notions of men who would be impacted by ED (e.g., ‘Tarzan brow beating sort of guy’) |

| Age: mean ± SD, 63.1±3.8 years; | |||

| SO: 94% Heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 100% HA (ADT), 83% RT, 11% RP; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Harden [2002] (64) USA; CX | 22 men; | NR | • Many men discussed the impact of tx on their erectile function and their feeling of being ‘incomplete’ or ‘harmless’ |

| Age: mean, 63.7 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: 59% advanced; | |||

| Tx type: 46% RP, 46% HA, 41% RT; | |||

| Time since tx: 82% receiving tx at time of focus group; | |||

| Sexual function: 59% self-reported sexual problems | |||

| Klaeson [2012] (65) Sweden; CX | 10 men interviewed between Apr and Aug 2008; | Asked to talk about being a man with PC and how this affected their sexuality | • Men were prepared to sacrifice their sexual function for the chance to stay alive however they missed their sexuality as part of their normal life; • Men described being only half the man they were before tx |

| Age: NR; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: NR; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Lavery [1999] (48) Australia; CX | 12 men; | NR | • Impotence impacted men’s feelings of masculinity, particularly younger men; • Sexual function was viewed as central to the ‘male psyche’ and its absence was difficult for some men. Men discussed having to just ‘accept it’ but in doing so they felt bitter and as if they were ‘only half a man’ |

| Age: mean, 62.4 years; | |||

| SO: Heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: 17% advanced; | |||

| Tx type: 75% surgery, 42% RT, 42% HA; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Letts [2010] (76), Canada; CX | 19 men; | NR | • Men reported that sexual changes had no impact on their masculinity; • One man felt that sexual function did impact his masculinity (not ‘a complete person’) but other aspects of life were more important; • Men experienced difficulty talking about their ED and this was attributed to masculine ideals such as emotional restraint (e.g., ‘men don’t like to talk about their feelings’) and stoicism (e.g. ‘their problem’, ‘suffer by themselves…in silence’); • Men discussed having little control over sexual changes (‘can’t help it’, ‘nothing you can do’) and having to accept (‘something have to live with’) that their ‘sex lives are over’ |

| Age: mean, 65.0 years; | |||

| SO: Heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 53% RT (EBR), 47% RP; | |||

| Time since tx: 12–60 months (mean, 30.0); | |||

| Sexual function: All men self-reported negative changes in their erections, orgasms, and sexual satisfaction post-tx | |||

| Maliski [2008] (66), USA; CX | 95 men (60 Latino, 35 African American); | Asked to talk about impact of PC tx-related symptoms on sense of masculinity | • PC tx and subsequent ED impacted men’s masculinity as an inability to please or take care of their partner, and feeling like a lesser man (‘less of a man’, ‘incomplete’); • Some men discussed that when they were with their ‘buddies’ they maintained a façade that they were sexually active because that is what men do; • Men minimized the threat of ED to their sense of masculinity by normalizing ED as part of the ageing process (already had ‘plenty of sex’, ‘much worse for younger men’); as their erectile function already having served its purpose (‘already had children’); or as a choice they needed to make between life and sex; • Acceptance (‘if it’s god’s will’) balanced with waiting and hoping (‘I’m only a year or so after my operation’, ‘giving it a little more time’) that their sexual function would return some time in the future was a strategy that some men used to enable them to live with ED; • Some men renegotiated what it meant to be a man (‘but I’m different’ to other men) by focusing more on relational aspects (e.g., talking with their partner) rather than physical aspects (e.g., ‘being a man is more than having sex’); • Men who had comorbid conditions that impacted their erectile function prior to tx saw ED post-tx as something that was already a part of their lives and had less impact (e.g., ‘already a member of the dead bird club’). Men who had partners with conditions that inhibited their sexual relationship similarly discussed ED as something that did not greatly impact their life |

| Age: ≥50 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: Latino men 67% surgery, 18% RT, 15% HA; Black men 46% surgery, 34% RT, 17% HA; | |||

| Time since tx: range, 0–24 months (approx.); | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Martin [2015] (74), Australia; CX | 11 men; | NR | • ED impacted men’s notion of manliness such that it was a ‘social stigma’ when sexual function was impaired and this had psychological effects |

| Age: NR; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: 82% localised, 18% locally advanced; | |||

| Tx type: 91% RP, 36% RT, 18% HA (ADT); | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Navon [2003] (67), Israel; CX | 15 men; | NR | • When informed by their doctor that PC tx would result in sexual dysfunction, men minimized this by focusing on the risk to their life; hoping sexual dysfunction was temporary; and redefining sex as being more than an erection and penetration. However, as tx proceeded men believed that tx ‘robbed them of what they loved best in life—sex’ and ‘the sparkle of things vanished’. Some men discussed that they no longer felt like men (e.g., ‘a man without urge and capacity for sex isn’t a man’); • In order to ‘pass as ordinary men’, some men engaged in ‘pseudo courtship’ (pretending to be interested in women and responding to women who showed sexual interest in them) and continued to talk and joke about sex with other men. Some men found this ‘sham’ to be upsetting but felt they had no choice but to conceal their sexual dysfunction and/or withdraw from social situations so others would not ask questions; • A common strategy adopted by men to cope with impotence was to attribute it to part of the normal aging process (e.g., ‘drop in sexual capacity’) and something experienced by many older men. Despite this strategy, men discussed struggling to put their memories of sexual pleasure out of their minds or get rid of them because they caused them grief |

| Age: mean, 70.0 years; | |||

| SO: heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: advanced; | |||

| Tx type: 100% HA, 40% RP, 33% RT; | |||

| Time since tx: ≥6 months prior to study; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Ng [2006] (77), Australia; CX | 20 men; | NR | • One man discussed that he no longer felt like a man because he had ED and found this difficult to understand and accept but minimized the impact of ED by ‘feeling relieved’ that he still had his life (e.g., ‘sex is not everything’) |

| Age: range, 50–70 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: HA with RT or RP; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| O’Brien [2007] (68), Scotland; CX | 59 men (including subgroup of PC patients) interviewed Jun 1999 to Feb 2001; | Presented statements about masculinity (e.g., ‘masculinity is dangerous to men’s health’) | • Men experienced sexual dysfunction after tx and this made them feel less like a man (e.g., ‘it lowers your machoness without a doubt’); • Although men noted that as they age they may experience a loss of their sex drive, some men discussed feeling ‘robbed’ of aspects of masculinity (ability to have an erection) before their time and found this to be devastating (e.g., ‘having it physically taken away early…that’s the hard bit’) |

| Age: NR; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: NR; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Oliffe [2005] (27), Australia; CX | 15 men; | NR | • Men noted feeling a ‘loss of potency’ which reflected not only their ability to have an erection but also their ‘sense of being a man’. One man discussed having ‘very black experiences’, ‘feeling old’, ‘worthless’, and trying to keep himself ‘invisible’; • Men reconsidered their sexual relationships as having a relationship beyond penetrative sex (e.g., touch) and some held hope that impotence would ‘settle down’ in the future; • Men acknowledged that forgoing sexual potency was the trade-off for living longer, others minimized the impact of impotence by stating that they had already ‘had their fun’ (e.g., ‘I’ve shown a lot of wild oats’), and one man used medication (e.g., Viagra) to help him ‘perform like the old days’ and ‘feel like a man’ |

| Age: mean, 57.0 years; | |||

| SO: heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: localised; | |||

| Tx type: RP; | |||

| Time since tx: mean, 21 months; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Oliffe [2006] (28), Australia; CX | 16 men interviewed during 2001; | NR | • Men minimized the impact of impotence on their masculinity with the view that sex was ‘not the most important thing in our lives’; • Other men discussed that without libido they were not thinking about or desiring sex so impotence was not difficult to accept and had little impact on their masculinity |

| Age: mean ± SD, 67.3±9.4 years; | |||

| SO: heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: advanced; | |||

| Tx type: 69% HA (ADT) + RT, 25% HA only (ADT), 6% HA (ADT) + RP; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Phillips [2000] (69), Canada; PR | 34 men; | NR | • Men described taking an optimistic approach to ED after surgery (e.g., too early to worry about sexual function and focus on getting well; • Secondary issue to incontinence; hopeful ED will get better with time); despite an optimistic approach some men reported that ED impacted their identity and self-worth as they questioned their masculinity and worth, and not feeling like a man (e.g., ‘you’re an ‘it’ instead of a man’) |

| Age: mean, 60.6 years; | |||

| SO: Heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: RP; | |||

| Time since tx: 2–2.5 months; | |||

| Sexual function: all men self-reported ED | |||

| Powel* [2005] (70), USA; CX | 71 men (of which 48 provided responses to an open-ended question); | NR | • Some men discussed that their lack of sexual function caused them to feel less like a man (e.g., ‘feel like I’ve lost my manhood’) and this was linked to depression and a fear that their wife would leave them; • Men minimized the impact of ED by rationalizing that it was a part of aging and would be more significant if they were younger |

| Age: mean, 57.0 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: RP; | |||

| Time since tx: mean, 16 months; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Rivers [2011] (49), USA; CX | 12 African-American men; | NR | • Some men discussed that loss of libido or ED impacted their sense of masculinity which decreased their self-confidence and esteem |

| Age: mean, 59.8 years; | |||

| SO: heterosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 42% RT, 33% surgery, 25% surgery + RT; | |||

| Time since tx: <60 months; | |||

| Sexual function: 92% self-reported ED | |||

| Seidler, [2015] (71) Australia; CX | 17 men (7 men with PC); | Open-ended question about cancer’s impact on identity and masculinity | • Men linked their sexual functioning to their masculinity and self-esteem (masculinity has ‘taken a hit’) |

| Age: range, 57–77 years; | |||

| SO: NR; | |||

| Cancer stage: NR; | |||

| Tx type: 86% surgery, 29% RT, 14% HA; | |||

| Time since tx: NR; | |||

| Sexual function: NR | |||

| Wittman* [2015] (50), USA; PR | 20 men interviewed Jan 2010 to Jun 2012; | NR | • Pre-tx, men expected that ED would not impact their sense of masculinity; • Post-tx, 75% of men felt that ED had impacted their masculinity |

| Age: mean, 60.2 years; | |||

| SO: 95% heterosexual, 5% homosexual; | |||

| Cancer stage: 80% localised, 20% locally advanced; | |||

| Tx type: 100% RP, 10% RT; | |||

| Time since tx: pre-tx and 3 months post-tx; | |||

| Sexual function (EPIC-S): mean ± SD, 46.5±25.1; 30% had ED |

*, quantitative and qualitative study. ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; AS, active surveillance; Br, brachytherapy; CX, cross-sectional; EBR; external beam radiation therapy; ED, erectile dysfunction; EPIC-S, expanded prostate cancer index composite-sexual functioning; HA, hormonal ablation (including ADT, orchiectomy); NR, not reported; PC, prostate cancer; PR, prospective; RP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiation therapy (including Br, EBR); SO, sexual orientation; Tx, treatment; WW, watchful waiting.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Center MM, Jemal A, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. International variation in prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates. Eur Urol 2012;61:1079-92. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.02.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.1, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11 [Internet]. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2013. Available online: http://globocan.iarc.fr, accessed on 14/11/2015.

- 3.American Cancer Society. Survival rates for prostate cancer. Retrieved 6th November, 2015. Available online: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/prostatecancer/detailedguide/prostate-cancer-survival-rates

- 4.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Prostate cancer in Australia. Cancer series no. 79. Retrieved 3rd November, 2015. Available online: http://www.aihw.gov.au/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=60129545133

- 5.Cancer Research UK. Prostate cancer statistics: prostate cancer survival. Retrieved 3rd November, 2015. Available online: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/prostate-cancer#heading-Two

- 6.Bernat JK, Wittman DA, Hawley ST, et al. Symptom burden and information needs in prostate cancer survivors: a case for tailored long-term survivorship care. BJU Int 2016;118:372-8. 10.1111/bju.13329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carlsson S, Drevin L, Loeb S, et al. Population-based study of long-term functional outcomes after prostate cancer treatment. BJU Int 2016;117:E36-45. 10.1111/bju.13179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canalichio K, Jaber Y, Wang R. Surgery and hormonal treatment for prostate cancer and sexual function. Transl Androl Urol 2015;4:103-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson E, Shinkins B, Frith E, et al. Symptoms, unmet needs, psychological well-being and health status in survivors of prostate cancer: implications for redesigning follow-up. BJU Int 2016;117:E10-9. 10.1111/bju.13122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2002;95:1773-85. 10.1002/cncr.10848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chung E, Brock G. Sexual rehabilitation and cancer survivorship: a state of art review of current literature and management strategies in male sexual dysfunction among prostate cancer survivors. J Sex Med 2013;10:102-11. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.03005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung E, Gillman M. Prostate cancer survivorship: a review of current literature in erectile dysfunction and the concept of penile rehabilitation following prostate cancer therapy. Med J Aust 2014;200:582-5. 10.5694/mja13.11028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salonia A, Burnett AL, Graefen M, et al. Prevention and management of postprostatectomy sexual dysfunctions part 1: Choosing the right patient at the right time for the right surgery. Eur Urol 2012;62:261-72. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.04.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salonia A, Burnett AL, Graefen M, et al. Prevention and management of postprostatectomy sexual dysfunctions part 2: Recovery and preservation of erectile function, sexual desire, and orgasmic function. Eur Urol 2012;62:273-86. 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.04.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tal R, Alphs HH, Krebs P, et al. Erectile function recovery rate after radical prostatectomy: a meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2009;6:2538-46. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01351.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alemozaffar M, Regan MM, Cooperberg MR, et al. Prediction of erectile function following treatment for prostate cancer. JAMA 2011;306:1205-14. 10.1001/jama.2011.1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, et al. Five-year outcomes after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: The prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:1358-67. 10.1093/jnci/djh259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goonewardene SS, Persad R. Psychosexual care in prostate cancer survivorship: a systematic review. Transl Androl Urol 2015;4:413-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helgason AR, Adolfsson J, Dickman P, et al. Waning sexual function--the most important disease-specific distress for patients with prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 1996;73:1417-21. 10.1038/bjc.1996.268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCabe MP, Althof SE. A systematic review of the psychosocial outcomes associated with erectile dysfunction: does the impact of erectile dysfunction extend beyond a man’s inability to have sex? J Sex Med 2014;11:347-63. 10.1111/jsm.12374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber BA, Sherwill-Navarro P. Psychosocial consequences of prostate cancer: 30 years of research. Geriatric Nursing 2005;26:166-75. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2005.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burns SM, Mahalik JR. Sexual functioning as a moderator of the relationship between masculinity and men’s adjustment following treatment for prostate cancer. Am J Mens Health 2008;2:6-16. 10.1177/1557988307304325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoyt MA, Stanton AL, Irwin MR, et al. Cancer-related masculine threat, emotional approach coping, and physical functioning following treatment for prostate cancer. Health Psychol 2013;32:66. 10.1037/a0030020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wall D, Kristjanson L. Men, culture and hegemonic masculinity: understanding the experience of prostate cancer. Nurs Inq 2005;12:87-97. 10.1111/j.1440-1800.2005.00258.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wittmann D, Northouse L, Foley S, et al. The psychosocial aspects of sexual recovery after prostate cancer treatment. Int J Impot Res 2009;21:99-106. 10.1038/ijir.2008.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapple A, Ziebland S. Prostate cancer: embodied experience and perceptions of masculinity. Sociology of Health & Illness 2002;24:820-41. 10.1111/1467-9566.00320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliffe J. Constructions of masculinity following prostatectomy-induced impotence. Soc Sci Med 2005;60:2249-59. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliffe J. Embodied masculinity and androgen deprivation therapy. Sociol Health Illn 2006;28:410-32. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2006.00499.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chambers SK, Schover L, Nielsen L, et al. Couple distress after localised prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:2967-76. 10.1007/s00520-013-1868-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hyde MK, Zajdlewicz L, Wootten AC, et al. Medical help-seeking for sexual concerns in prostate cancer survivors. Sex Med 2016;4:e7-e17. 10.1016/j.esxm.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oliffe J. Positioning prostate cancer as the problematic third testicle. In: Broom A, Tovey P. editors. Men’s health: Body, identity and social context. London: Wiley Ltd.; 2009:33-62. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chambers SK, Hyde MK, Oliffe JL, et al. Measuring masculinity in the context of chronic disease. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 2016;17:228-42. 10.1037/men0000018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allensworth-Davies D, Talcott JA, Heeren T, et al. The health effects of masculine self-esteem following treatment for localized prostate cancer among gay men. LGBT Health 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark JA, Wray N, Brody B, et al. Dimensions of quality of life expressed by men treated for metastatic prostate cancer. Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1299-309. 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00058-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clark JA, Inui TS, Silliman RA, et al. Patients' perceptions of quality of life after treatment for early prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3777-84. 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaider T, Manne S, Nelson C, Mulhall J, Kissane D. Loss of masculine identity, marital affection, and sexual bother in men with localized prostate cancer. J Sex Med 2012;9:2724-32. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02897.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galbraith ME, Ramirez JM, Pedro LW. Quality of life, health outcomes, and identity for patients with prostate cancer in five different treatment groups. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001;28:551-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molton IR, Siegel SD, Penedo FJ, et al. Promoting recovery of sexual functioning after radical prostatectomy with group-based stress management: the role of interpersonal sensitivity. J Psychosom Res 2008;64:527-36. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davison BJ, So AI, Goldenberg SL. Quality of life, sexual function and decisional regret at 1 year after surgical treatment for localized prostate cancer. BJU Int 2007;100:780-5. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07043.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharpley CF, Birsika V, Denham JW. Factors associated with feelings of loss of masculinity in men with prostate cancer in the RADAR trial. Psychooncology 2014;23:524-30. 10.1002/pon.3448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hoyt MA, Carpenter KM. Sexual self-schema and depressive symptoms after prostate cancer. Psychooncology 2015;24:395-401. 10.1002/pon.3601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Shaughnessy PK, Ireland C, Pelentsov L, et al. Impaired sexual function and prostate cancer: a mixed method investigation into the experiences of men and their partners. J Clin Nurs 2013;22:3492-502. 10.1111/jocn.12190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Appleton L, Wyatt D, Perkins E, et al. The impact of prostate cancer on men's everyday life. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2015;24:71-84. 10.1111/ecc.12233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arrington MI. "I don't want to be an artificial man": Narrative reconstruction of sexuality among prostate cancer survivors. Sexuality and Culture 2003;7:30-58. 10.1007/s12119-003-1011-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arrington MI. Theorizing about social support and health communication in a prostate cancer support group. J Psychosoc Oncol 2010;28:260-8. 10.1080/07347331003678337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arrington MI. Uncertainty and stigma in the experiences of prostate cancer survivors: A thematic analysis of narrative elements. Illness, Crisis, & Loss 2015;23:242-60. 10.1177/1054137315585684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagen B, Grant-Kalischuk R, Sanders J. Disappearing floors and second chances: men's journeys of prostate cancer. Int J Mens Health 2007;6:201-23. 10.3149/jmh.0603.201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lavery JF, Clarke VA. Prostate cancer: patients' and spouses' coping and marital adjustment. Psychology, Health & Medicine 1999;4:289-302. 10.1080/135485099106225 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rivers BM, August EM, Gwede CK, et al. Psychosocial issues related to sexual functioning among African-American prostate cancer survivors and their spouses. Psychooncology 2011;20:106-10. 10.1002/pon.1711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wittmann D, Carolan M, Given B, et al. What couples say about their recovery of sexual intimacy after prostatectomy: Toward the development of a conceptual model of couples' sexual recovery after surgery for prostate cancer. J Sex Med 2015;12:494-504. 10.1111/jsm.12732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arrington MI. Prostate cancer and the social construction of masculine sexual identity. Int J Mens Health 2008;7:299-306. 10.3149/jmh.0703.299 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Broom A. Prostate cancer and masculinity in Australian society: a case of stolen identity? Int J Mens Health 2004;3:73-91. 10.3149/jmh.0302.73 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chambers SK, Lowe A, Hyde MK, et al. Defining young in the context of prostate cancer. Am J Mens Health 2015;9:103-14. 10.1177/1557988314529991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berterö C. Altered sexual patterns after treatment for prostate cancer. Cancer Practice 2001;9:245-51. 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2001.009005245.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Moraes Lopes MH, Higa R, et al. Life experiences of Brazilian men with urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012;39:90-4. 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182383eeb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dieperink KB, Wagner L, Hansen S, et al. Embracing life after prostate cancer. A male perspective on treatment and rehabilitation. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013;22:549-58. 10.1111/ecc.12061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ervik B, Nordøy T, Asplund K. Hit by waves---living with local advanced or localized prostate cancer treated with endocrine therapy or under active surveillance. Cancer Nursing 2010;33:382-9. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181d1c8ea [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ervik B, Asplund K. Dealing with a troublesome body: a qualitative interview study of men's experiences living with prostate cancer treated with endocrine therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2012;16:103-8. 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans J, Butler L, Etowa J, et al. Gendered and cultured relations: exploring African Nova Scotians' perceptions and experiences of breast and prostate cancer. Res Theory Nurs Pract 2005;19:257-73. 10.1891/rtnp.2005.19.3.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fergus KD, Gray RE, Fitch MI. Sexual dysfunction and the preservation of manhood: experiences of men with prostate cancer. J Health Psychol 2002;7:303-16. 10.1177/1359105302007003223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gannon K, Guerro-Blanco M, Patel A, et al. Re-constructing masculinity following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Aging Male 2010;13:258-64. 10.3109/13685538.2010.487554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Embodying sexual subjectivity after cancer: a qualitative study of people with cancer and intimate partners. Psychol Health 2013;28:603-19. 10.1080/08870446.2012.737466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hamilton K, Chambers SK, Legg M, et al. Sexuality and exercise in men undergoing androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:133-42. 10.1007/s00520-014-2327-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harden J, Schafenacker A, Northouse L, et al. Couples' experiences with prostate cancer: focus group research. Oncol Nurs Forum 2002;29:701-9. 10.1188/02.ONF.701-709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klaeson K, Sandell K, Bertero CM. Sexuality in the context of prostate cancer narratives. Qual Health Res 2012;22:1184-94. 10.1177/1049732312449208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maliski SL, Rivera S, Connor S, et al. Renegotiating masculine identity after prostate cancer treatment. Qual Health Res 2008;18:1609-20. 10.1177/1049732308326813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Navon L, Morag A. Advanced prostate cancer patients' ways of coping with the hormonal therapy's effect on body, sexuality, and spousal ties. Qual Health Res 2003;13:1378-92. 10.1177/1049732303258016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.O'Brien R, Hart GJ, Hunt K. "Standing out from the herd": men renegotiating masculinity in relation to their experience of illness. Int J Mens Health 2007;6:178-200. 10.3149/jmh.0603.178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Phillips C, Gray RE, Fitch MI, et al. Early postsurgery experience of prostate cancer patients and spouses. Cancer Practice 2000;8:165-71. 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2000.84009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Powel LL, Clark JA. The value of the marginalia as an adjunct to structured questionnaires: experiences of men after prostate cancer surgery. Qual Life Res 2005;14:827-35. 10.1007/s11136-004-0797-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seidler ZE, Lawsin CR, Hoyt MA, et al. Let's talk about sex after cancer: exploring barriers and facilitators to sexual communication in male cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2016;25:670-6. 10.1002/pon.3994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bokhour BG, Clark JA, Inui TS, et al. Sexuality after treatment for early prostate cancer: exploring the meanings of "erectile dysfunction". J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:649-55. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00832.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clark JA, Bokhour BG, Inui TS, et al. Measuring patients' perceptions of the outcomes of treatment for early prostate cancer. Med Care 2003;41:923-36. 10.1097/00005650-200308000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martin E, Bulsara C, Battaglini C, et al. Breast and prostate cancer survivor responses to group exercise and supportive group psychotherapy. J Psychosoc Oncol 2015;33:620-34. 10.1080/07347332.2015.1082166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gray RE, Fitch MI, Fergus KD, et al. Hegemonic masculinity and the experience of prostate cancer: a narrative approach. Journal of Aging & Identity 2002;7:43-62. 10.1023/A:1014310532734 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Letts C, Tamlyn K, Byers ES. Exploring the impact of prostate cancer on men's sexual well-being. J Psychosoc Oncol 2010;28:490-510. 10.1080/07347332.2010.498457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ng C, Kristjanson LJ, Medigovich K. Hormone ablation for the treatment of prostate cancer: the lived experience. Urologic Nursing 2006;26:204-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lucas MD, Strijdom SC, Berk M, et al. Quality of life, sexual functioning and sex role identity after surgical orchidectomy in patients with prostatic cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol 1995;29:497-500. 10.3109/00365599509180033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chambers SK, Dunn J, Lazenby M, et al. ProsCare: a psychological care model for men with prostate cancer. Available online: http://www.prostate.org.au/media/195765/proscare_monograph_final_2013.pdf