Abstract

Objective Diabetes is a negative predictor in coronary artery disease patients. Since the introduction of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), PCI has evolved through technological advances in devices, improvements in operators' techniques and the establishment of effective therapeutic protocols. The aim of this study is to examine the changes in the clinical outcomes following PCI in patients with diabetes.

Methods We compared the clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes following PCI from 1984 to 2010 at Juntendo University over three eras (plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA)-, bare metal stents (BMS)- and drug-eluting stents (DES)-eras). The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction, non-fatal stroke and repeat revascularization within 3 years after the index PCI.

Results A total of 1,584 patients were examined. The baseline characteristics became unfavorable over time with regard to age, prevalence of hypertension, presentation with acute coronary syndrome and a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction. The administration of aspirin, statins and β-blockers increased over time. The event-free survival rate for the 3-year cardiovascular events was lower in the DES-era. The adjusted relative risk reduction for 3-year cardiovascular events was 46 % in the DES-era compared with the POBA-era.

Conclusion The incidence of 3-year cardiovascular events decreased from 1984 to 2010 in patients with diabetes following PCI, despite the higher risk profiles in the DES-era.

Keywords: diabetes, balloon angioplasty, bare metal stent, drug-eluting stent

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is known to be associated with worse clinical outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) (1,2). Since the introduction of plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) for CAD in 1977 (3), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has evolved through numerous technological advances of devices, improvements in operators' techniques and the establishment of therapeutic protocols for secondary prevention (4-6). The advent of drug-eluting stents (DES) has significantly reduced the occurrence of target lesion revascularization from 20-30% in the bare metal stents (BMS) era to below 10% (7,8). However, the age and prevalence of comorbid diseases in patients who undergo PCI have increased with the aging society. Recently, we reported that the clinical outcomes following PCI improved during the POBA-, BMS- and DES-era (9). It is of interest to elucidate the temporal trends of the clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes following PCI.

We analyzed the data from our PCI database of Juntendo University Hospital (Tokyo, Japan) from January 1984 to February 2010. This database has been maintained since the introduction of PCI in our institution. The study population was divided into three groups according to the time period of the index PCI (the POBA-era, January 1984 - December 1997; the BMS-era, January 1998 - July 2004; and the DES-era, August 2004 - February 2010).

Materials and Methods

Clinical outcomes

The primary endpoint was cardiovascular events including all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), non-fatal stroke and repeat revascularization that occurred within 3 years after the index PCI procedure. Information regarding the clinical outcomes was collected during clinical visits, via telephone interviews or from the referring physician. Our institutional review board approved the protocol of this study, which was performed in accordance with the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki and our institutional ethics policy.

Definitions

Diabetes was defined as glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) value ≥6.5%, based on a previous diagnosis from medical records or being treated with any oral anti-diabetic agents or insulin. We converted HbA1c (Japan Diabetes Society [JDS]) values to HbA1c (NGSP) units using the following equation: NGSP (%) = 1.02× JDS (%) + 0.25% (10). Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg or treatment with anti-hypertensive medications. Dyslipidemia was defined by a previous diagnosis from medical records, lipid profiles, i.e., triglycerides (TG) ≥150 mg/dL, low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) ≥140 mg/dL or high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) <40 mg/dL or being treated with anti-dyslipidemic medications. We defined current smokers as individuals who smoked at the time of admission or had quit within one year before the study period. Renal dysfunction was defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60 mL·min-1·1.73 m2 calculated using the modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) equation modified with a Japanese coefficient using baseline serum creatinine (11). MI was diagnosed in the presence of 2 of the following 3 criteria: (1) typical chest pain for at least 20 minutes, (2) an increased serum creatine kinase level reaching twice the upper normal range, and (3) a new Q wave on electrocardiography. Procedural success of PCI was defined as a decrease in the residual luminal diameter stenosis to <50% or an achievement of thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) grade 3 in the final angiogram of the procedure.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean values with standard deviation. The categorical data were expressed as counts and percentages. Continuous variables were compared using the one-way analysis of variance followed by a post hoc analysis using Dunnett's test for multiple comparisons. The POBA-era served as a control group in the post hoc analysis. The continuous variables demonstrating statistical significance in the analysis are marked with *. Categorical variables were analyzed by either the chi-square test or Fisher's exact probability test. An analysis of intergroup comparisons with the POBA-era group for categorical variables was calculated with Bonferroni's correction. In the analysis, a p value of below 0.025 was considered to be significant. The categorical variables demonstrating statistical significance in the analysis are marked with †. Unadjusted cumulative event rates for 3-year cardiovascular events were estimated by Kaplan-Meier methods and compared using the log-rank test across the three groups. To identify the predictor for clinical outcomes, an univariate Cox regression analysis was performed including age, male gender, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, dyslipidemia, current smoker, family history of CAD, aspirin-use, β-blocker-use, calcium-channel blocker-use, statin-use, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB)-use, oral anti-diabetic agent-use, insulin-use, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG, eGFR, hemoglobin, hemoglobin A1c, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), acute coronary syndrome (ACS), multivessel disease (MVD) and PCI eras (with the POBA-era as the reference) as independent variables. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals were also calculated. Variables with p<0.1 in the analysis were analyzed by the multivariable Cox regression analysis. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All data were analyzed using the JMP software program version 10.0 for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

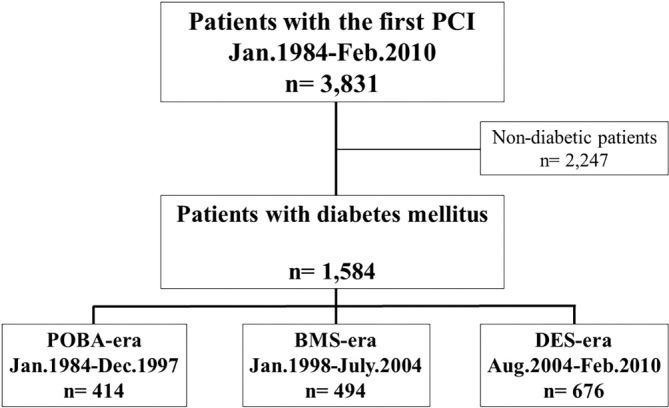

A flow chart of the study population is provided as Fig. 1. A total of 1,584 patients were analyzed (the POBA-era, n=414; the BMS-era, n=494; and the DES-era, n=676). Data regarding medication-use were available for 364 of the 414 (87.9%) patients in the POBA-era, 480 of the 494 (97.2%) patients in the BMS-era and 675 of the 676 (99.9%) patients in the DES-era. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The average age was the highest in the DES-era, and a higher prevalence of hypertension was observed in the DES- and BMS-eras than in the POBA-era. The percentage of current smokers was higher in the POBA-era than the other eras. The lipid profiles were more favorable in the DES- and BMS-eras than in the POBA-era, and the success rate of PCI was also higher in these eras than in the POBA-era. In addition, the DES- and BMS- eras included more patients who presented with ACS at the time of the initial procedure. The use of evidence-based medical therapy (i.e., aspirin, statin, β-blocker and ACEI/ARB) for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events significantly increased over time. The percentage of patients taking oral anti-diabetic agents and insulin were the lowest in the POBA-era (Table 2). The lesion characteristics are shown in Table 3. The diseased vessels tended to differ among the groups, and a higher prevalence of MVD was observed in the DES- and BMS-eras than in the POBA-era.

Figure 1.

A flow chart of the study population. Legend: A total of 1,584 patients with diabetes mellitus who underwent the first PCI in our institution were analyzed in this study.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| POBA era | BMS era | DES era | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 414) | (n = 494) | (n = 676) | ||

| Age, year | 61.1 ± 9.1 | 63.8 ± 9.7* | 66.6 ± 10.0* | < 0.0001 |

| Male, n (%) | 339 (81.9) | 401 (81.2) | 552 (81.7) | 0.9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.5 ± 4.9 | 24.3 ± 3.7 | 24.4 ± 3.6 | 0.7 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 247 (60.1) | 324 (65.6) | 515 (76.2) † | < 0.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 378 (71.2) | 323 (65.8) | 511 (75.6) | 0.001 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 198 (48.7) | 111 (22.5) † | 183 (27.1) † | < 0.0001 |

| Family history, n (%) | 128 (31.5) | 144 (29.3) | 181 (26.8) | 0.3 |

| Low density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 126.2 ± 42.6 | 114.5 ± 31.6* | 110.2 ± 32.7* | < 0.0001 |

| High density lipoprotein cholesterol, mg/dL | 41.4 ± 12.0 | 42.2 ± 13.5 | 43.8 ± 13.4* | 0.0095 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 198.2 ± 47.4 | 187.8 ± 36.9* | 186.0 ± 38.6* | < 0.0001 |

| Triglyceride, mg/dL | 152.3 ± 81.3 | 139.6 ± 80.2* | 140.5 ± 80.3* | 0.03 |

| HbA1c, % | 7.6 ± 3.1 | 7.3 ± 1.5* | 7.3 ± 1.3* | 0.009 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.5 ± 1.8 | 13.0 ± 1.8* | 13.3 ± 1.9 | 0.002 |

| LVEF, % | 64.4 ± 13.3 | 63.4 ± 13.2 | 59.6 ± 13.1* | < 0.0001 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 63.9 ± 26.4 | 67.1 ± 23.8 | 65.1 ± 24.8 | 0.2 |

| Clinical presentation | < 0.0001 | |||

| Acute coronary syndrome, n (%) | 75 (18.1) | 159 (32.2) | 186 (27.5) | |

| Stable coronary artery disease, n (%) | 339 (81.9) | 335 (67.8) | 490 (72.5) | |

| Success rate, n (%) | 373 (90.1) | 476 (96.4) † | 647 (95.7) † | < 0.0001 |

| Type of procedure, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| POBA | 390 (94.2) | 96 (19.6) | 40 (6.1) | |

| BMS | 24 (5.8) | 395 (80.5) | 222 (33.7) | |

| DES | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 396 (60.2) |

BMI: body mass index, HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty, BMS: bare metal stents, DES: drug-eluting stents

Table 2.

Medication Use.

| POBA era | BMS era | DES era | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 364) | (n = 480) | (n = 675) | ||

| Aspirin | 275 (75.6) | 447 (93.1) † | 639 (94.6) † | < 0.0001 |

| Dual-antiplatelet agent | 164 (45.2) | 314 (65.4) † | 592 (87.7) † | < 0.0001 |

| Statin | 73 (20.1) | 195 (40.3) | 436 (67.5) † | < 0.0001 |

| ACEI/ARB | 53 (14.6) | 218 (45.4) † | 388 (57.5) † | < 0.0001 |

| β-blocker | 98 (26.9) | 189 (39.4) † | 365 (54.1) † | < 0.0001 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 181 (49.7) | 182 (37.9) † | 260 (38.5) † | 0.0007 |

| Insulin | 17 (4.7) | 110 (22.9) † | 156 (23.1) † | < 0.0001 |

| Oral anti-diabetic agents | 101 (27.7) | 249 (51.9) † | 384 (56.9) † | < 0.0001 |

ACEI: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB: angiotensin receptor blocker

Table 3.

Lesion Characteristics.

| POBA era | BMS era | DES era | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n= 414) | (n = 494) | (n = 676) | ||

| Diseased vessel | 0.0002 | |||

| LAD | 209 (50.5) | 220 (44.5) | 294 (43.5) | |

| LCX | 70 (16.9) | 94 (19.0) | 134 (19.8) | |

| RCA | 106 (25.6) | 157 (31.8) | 218 (32.3) | |

| LMT | 4 (1.0) | 5 (1.0) | 19 (2.8) | |

| Others | 25 (6.0) | 18 (3.6) | 11 (1.6) | |

| Number of diseased vessel | 1.5 ±0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.8* | 2.0 ± 0.8* | < 0.0001 |

| Multivessel disease | 162 (41.1) | 260 (52.6) † | 444 (66.3) † | < 0.0001 |

| QCA | ||||

| Minimal lumen diameter (pre), mm | 0.52 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.38 ± 0.3* | < 0.0001 |

| Minimal lumen diameter (post), mm | 2.03 ± 0.6 | 2.59 ± 0.7* | 2.61 ± 0.6* | < 0.0001 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.16 ± 0.43 | 2.97 ± 0.42 | < 0.0001 | |

| Stent length, mm | 16.8 ± 4.09 | 20.1 ± 6.14 | < 0.0001 |

LAD: left anterior descending artery, LCX: left circumflex, RCA: right coronary artery, LMT: left main trunk, QCA: quantitative coronary angiography

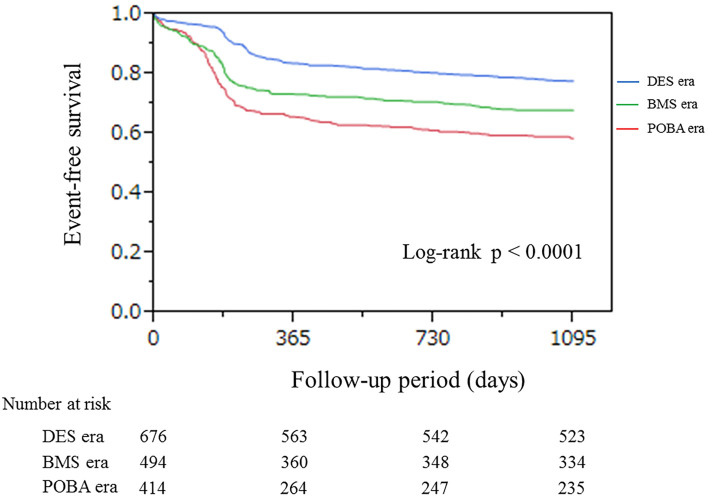

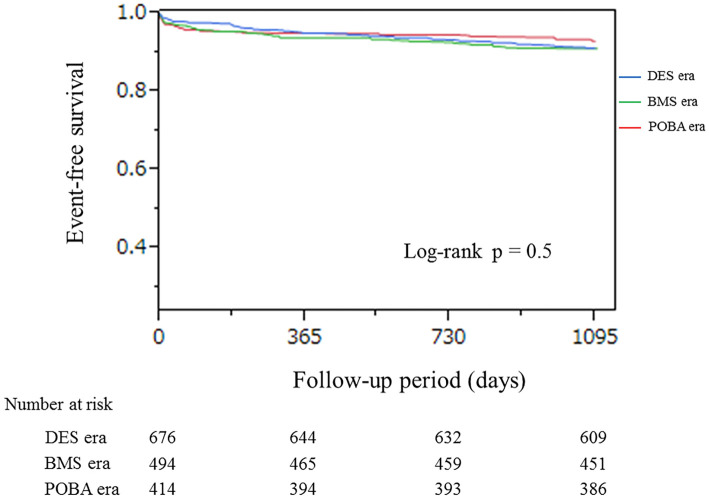

Information regarding the 3-year clinical outcomes was collected from all patients in this study. The unadjusted cumulative event-free survival rate for 3-year cardiovascular events was significantly different across the three eras (Fig. 2). For the 3-year all-cause mortality and ACS, no difference was found among the groups (Fig. 3). Detailed information regarding the cause of death is described in Table 4. The adjusted relative risk reduction for 3-year cardiovascular event was 41 % in DES-era compared with POBA-era. No significant difference was observed in the incidence of 3-year cardiovascular events between the BMS- and POBA-eras. A higher eGFR and higher LVEF were also associated with a lower incidence of 3-year cardiovascular events (Table 5). No significant difference was observed in the 3-year all-cause mortality and ACS between the DES- and the POBA-eras or the BMS- and the POBA-eras according to a univariate Cox regression analysis. After controlling for variables, a lower BMI, eGFR and LVEF, insulin-use and ACS were associated with increased 3-year all-cause mortality and ACS (Table 6).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for 3-year cardiovascular events. Legend: Kaplan-Meier curves for 3-year cardiovascular events show a significant difference across the three eras. The event rate was the lowest in the DES-era.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for 3-year all-cause mortality and ACS. Legend: No significant differences between eras were observed for all-cause mortality or ACS occurrence.

Table 4.

Causes of Death.

| POBA era | BMS era | DES era | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7 | ||||

| Cardiovascular events, n (%) | 31 (42.5) | 48 (35.0) | 38 (38.8) | |

| Cerebrovascular events, n (%) | 6 (8.2) | 10 (7.3) | 5 (5.1) | |

| Malignancy, n (%) | 22 (30.1) | 38 (27.7) | 31 (31.6) | |

| Infection, n (%) | 4 (5.5) | 12 (8.8) | 10 (10.2) | |

| Others, n (%) | 10 (13.7) | 29 (21.2) | 14 (14.3) |

Table 5.

Cox Regression Analysis for 3-year Cardiovascular Events.

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| BMI, 1 kg/m2 increase | 0.98 | 0.95-1.003 | 0.09 | 0.98 | 0.95-1.006 | 0.1 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1.24 | 1.02-1.51 | 0.03 | 1.29 | 1.01-1.63 | 0.1 |

| eGFR, 1mL/min/1.73m2 increase | 0.996 | 0.992-0.999 | 0.02 | 0.995 | 0.99-0.999 | 0.03 |

| LVEF, 1 % increase | 0.99 | 0.98-0.998 | 0.01 | 0.987 | 0.98-0.99 | 0.002 |

| β-blocker | 0.85 | 0.71-1.03 | 0.09 | 1.06 | 0.85-1.32 | 0.6 |

| Statin | 0.69 | 0.57-0.85 | 0.0003 | 0.84 | 0.67-1.05 | 0.1 |

| Aspirin | 0.60 | 0.46-0.78 | 0.0003 | 0.88 | 0.59-1.33 | 0.5 |

| Dual-antiplatelet agent | 0.66 | 0.55-0.80 | < 0.0001 | 0.82 | 0.62-1.09 | 0.2 |

| BMS era (POBA era as reference) | 0.68 | 0.55-0.84 | 0.0004 | 0.85 | 0.62-1.18 | 0.3 |

| DES era (POBA era as reference) | 0.43 | 0.34-0.53 | < 0.0001 | 0.59 | 0.42-0.85 | 0.004 |

BMI: body mass index, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, BMS: bare metal stents, POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty, DES: drug-eluting stents

Table 6.

Cox Regression Analysis for 3-year All-cause Mortality and ACS.

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age, 1year increase | 1.04 | 1.03-1.07 | < 0.0001 | 1.02 | 0.97-1.05 | 0.3 |

| Male gender | 0.67 | 0.47-1.04 | 0.08 | 0.95 | 0.52-1.82 | 0.9 |

| BMI, 1 kg/m2 increase | 0.95 | 0.91-0.99 | 0.04 | 0.91 | 0.83-0.99 | 0.04 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.63 | 0.44-0.90 | 0.01 | 0.96 | 0.54-1.70 | 0.9 |

| Current smoking | 0.54 | 0.34-0.82 | 0.003 | 0.79 | 0.40-1.48 | 0.5 |

| Hemoglobin, 1g/dL increase | 0.79 | 0.72-0.87 | < 0.0001 | 0.94 | 0.79-1.13 | 0.9 |

| eGFR, 1 mL/min/1.73m2 increase | 0.97 | 0.965-0.98 | < 0.0001 | 0.99 | 0.97-0.997 | 0.008 |

| LVEF, 1 % increase | 0.96 | 0.95-0.97 | < 0.0001 | 0.98 | 0.96-0.99 | 0.04 |

| β-blocker | 0.71 | 0.49-1.02 | 0.06 | 0.55 | 0.48-1.45 | 0.5 |

| Statin | 0.60 | 0.41-0.87 | 0.006 | 0.66 | 0.36-1.19 | 0.2 |

| Aspirin | 0.43 | 0.28-0.68 | 0.0005 | 1.02 | 0.41-2.90 | 0.9 |

| Dual-antiplatelet agent | 0.62 | 0.46-0.84 | 0.002 | 0.68 | 0.38-1.26 | 0.2 |

| Insulin | 1.90 | 1.28-2.80 | 0.002 | 2.24 | 1.20-3.99 | 0.01 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1.82 | 1.27-2.57 | 0.0012 | 1.92 | 1.05-3.47 | 0.03 |

| Multivessel disease | 1.66 | 1.16-2.42 | 0.005 | 0.94 | 0.54-1.64 | 0.8 |

| BMS era (POBA era as reference) | 1.28 | 0.81-2.07 | 0.3 | |||

| DES era (POBA era as reference) | 1.24 | 0.80-1.96 | 0.3 |

BMI: body mass index, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, BMS: bare metal stents, POBA: plain old balloon angioplasty, DES: drug-eluting stents

Discussion

The main findings of this study examining the clinical outcomes following PCI in patients with diabetes are as follows: 1) the baseline characteristics became increasingly unfavorable over the examined 26-year period in terms of a higher age and higher prevalence of comorbid diseases (hypertension, dyslipidemia and MVD); 2) the success rate of PCI and the use of evidence-based medical therapy for secondary prevention have increased over time; and 3) no significant difference was observed in the 3-year all-cause mortality or ACS, despite the higher risk profiles in the DES-era. Furthermore, the incidence of 3-year cardiovascular events significantly decreased over time. These findings suggest that the improvement of PCI devices and the increased use of evidence-based medical therapy for secondary prevention has led to improved long-term clinical outcomes following PCI, even in the high risk patients with diabetes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study examining clinical outcomes following PCI across the POBA-, BMS- and DES-eras in diabetic patients who are at high risk for future cardiovascular events.

To date, there are conflicting data regarding the clinical outcomes in diabetic patients following PCI. Holper et al. reported significant improvements in mortality at 1 year post-PCI in the diabetic patients treated with oral agents who underwent PCI during the study period from 1997 to 2006, whereas the clinical outcomes in insulin-treated diabetic patients remained unchanged in that study (12). Similarly, a recent report showed that the in-hospital mortality in diabetic patients who underwent PCI remained unchanged during the study period from 2001 to 2011 (13). Although both the timing in which each study was conducted and the length of the follow-up period varied from one another and those of the current study, these results consistently showed no significant improvements in the mortality rate of diabetic patients following PCI, despite the advances in interventional techniques, devices and the increased use of guideline-recommended medical therapy. The fact that there was no change in the long-term adjusted mortality can be explained by the differences in the baseline characteristics, such as a higher age, more comorbid diseases and more complex coronary artery lesions. In fact, the average age, the prevalence of hypertension and dyslipidemia and the percentages of MVD were all higher in the DES-era than in the previous eras in our study population. The similar mortality rate across the time period may be explained by the relatively short follow-up period in this study. The STENO-II study demonstrated the impact of an intensive risk reduction program with multiple drug combinations on the reduction of mortality during a follow-up period of 13 years (14). In our study, the use of evidence-based medical therapy (i.e., aspirin, statins, β-blockers and ACEI/ARBs) for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events significantly increased from the POBA-era to the DES-era. Therefore, an extended period might be required to achieve a reduced mortality rate through optimal medical therapy.

Regarding the incidence of cardiovascular event, including all-cause mortality, MI, stroke and repeat revascularization, significant improvements were observed across the three eras in this study. Because diabetes is considered to be a predictor for a higher rate of repeat revascularization, even in the current DES-era (2,15-17), it is notable that the incidence of cardiovascular events improved over time in diabetic patients in our study. Improvements in cardiovascular events over the 26-year period of this study could be explained by the following: advances in PCI devices such as the introduction of DES, a high rate of PCI success and the increased use of evidence-based therapies for secondary prevention and smoking cessation. Indeed, the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) has previously shown that adherence to guideline-recommended medical therapy for secondary prevention yielded favorable clinical outcomes after acute coronary events (18).

The present study could help us ascertain the importance of advances in PCI technology, medical therapy for secondary prevention and smoking cessation in reducing cardiovascular events, even in high-risk patients with diabetes following PCI.

Future perspectives

The present study and previous reports indicate the importance of adhering to evidence-based medical and non-pharmacological therapy for secondary prevention and to further establish renewed measures to reduce fatal cardiovascular events. Considering that increased physical activity and nutrition therapy have been demonstrated to have positive effects on lowering cardiovascular events (19,20), future studies considering non-pharmacological treatments when elucidating factors associated with the clinical outcomes of CAD patients are necessary.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, this study was conducted at a single institution, and the study population was small, limiting the generalizability of our results. However, our data are important because PCI has been utilized in our institution from the beginning of the use of PCI in Japan. Second, there was a lack of data regarding medication use and detailed information about oral anti-diabetic agents, which are considered to be important in this study. Third, because of the long-term follow-up period across three generations of PCI, some undetermined factors that were not assessed in this study may have affected the incidence of clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

The long-term clinical outcomes following PCI in patients with diabetes in our institution were more favorable in the DES-era than in the other eras, mainly due to the reduction in repeat revascularization, despite the higher risk profiles of the patients.

Author's disclosure of potential Conflicts of Interest (COI).

Katsumi Miyauchi: Honoraria, MSD, AstraZeneca, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Sanofi-Aventis, Shionogi, Daiichi-Sankyo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Astellas Pharma and Novartis Pharma. Hiroyuki Daida: Honoraria, MSD, AstraZeneca, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Sanofi-Aventis, GlaxoSmithKline, Shionogi, Daiichi-Sankyo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Pfizer and Astellas Pharma; Research funding, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim, Astellas Pharma, Novartis Pharma, MSD, Sanofi-Aventis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Pfizer, Kowa Pharmaceutical, Shionogi, AstraZeneca, Teijin and Morinaga Milk Industry.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by a grant for scientific research from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (23591063). We gratefully acknowledge the contributions made by Ms. Yumi Nozawa and Ms. Ayako Onodera in the data collection and management.

References

- 1. Hlatky MA, Boothroyd DB, Bravata DM, et al. Coronary artery bypass surgery compared with percutaneous coronary interventions for multivessel disease: a collaborative analysis of individual patient data from ten randomised trials. Lancet 373: 1190-1197, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hong SJ, Kim MH, Ahn TH, et al. Multiple predictors of coronary restenosis after drug-eluting stent implantation in patients with diabetes. Heart 92: 1119-1124, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grüntzig AR, Senning A, Siegenthaler WE. Nonoperative dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis: percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. N Engl J Med 301: 61-68, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, TAXUS-IV Investigators, et al. ; A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 350: 221-231, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stone GW, Rizvi A, Newman W, SPIRIT IV Investigators, et al. ; Everolimus-eluting versus paclitaxel-eluting stents in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 362: 1663-1674, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, SIRIUS Investigators, et al. ; Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med 349: 1315-1323, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, RAVEL Study Group, et al. ; Randomized Study with the Sirolimus-Coated Bx Velocity Balloon-Expandable Stent in the Treatment of Patients with de Novo Native Coronary Artery Lesions. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med 346: 1773-1780, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Babapulle MN, Joseph L, Belisle P, Brophy JM, Eisenberg MJ. A hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials of drug-eluting stents. Lancet 364: 583-591, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Naito R, Miyauchi K, Konishi H, et al. Temporal trends in clinical outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention 1984-2010 -Report from the Juntendo PCI registry. Circ J 80: 93-100, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kashiwagi A, Kasuga M, Araki E, Committee on the Standardization of Diabetes Mellitus-Related Laboratory Testing of Japan Diabetes Society, et al. ; International clinical harmonization of glycated hemoglobin in Japan: From Japan Diabetes Society to National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program values. J Diabetes Investig 3: 39-40, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Collaborators developing the Japanese equation for estimated GFR, et al. ; Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 982-992, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holper EM, Abbott JD, Mulukutla S, et al. Temporal changes in the outcomes of patients with diabetes mellitus undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute dynamic registry. Am Heart J 161: 397-403, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elbarouni B, Ismaeil N, Yan RT, et al. Temporal changes in the management and outcome of Canadian diabetic patients hospitalized for non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J 162: 347-355, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lopez-de-Andres A, Jimenez-García R, Hernandez-Barrera V, et al. National trends in utilization and outcomes of coronary revascularization procedures among people with and without type 2 diabetes in Spain (2001-2011). Cardiovasc Diabetol 13: 3, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358: 580-591, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taniwaki M, Stefanini GG, Silber S, RESOLUTE All-Comers Investigators, et al. ; 4-year clinical outcomes and predictors of repeat revascularization in patients treated with new-generation drug-eluting stents: a report from the RESOLUTE All-Comers trial (A Randomized Comparison of a Zotarolimus-Eluting Stent With an Everolimus-Eluting Stent for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol 63: 1617-1625, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kastrati A, Massberg S, Ndrepepa G. Is diabetes the achilles' heel of limus-eluting stents? Circulation 124: 869-872, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fox KA, Steg PG, Eagle KA, GRACE Investigators, et al. ; Decline in rates of death and heart failure in acute coronary syndromes, 1999-2006. JAMA 297: 1892-1900, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Knoops KT, de Groot LC, Kromhout D, et al. Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: the HALE project. JAMA 292: 1433-1439, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Booth JN 3rd, Levitan EB, Brown TM, Farkouh ME, Safford MM, Muntner P. Effect of sustaining lifestyle modifications (nonsmoking, weight reduction, physical activity, and mediterranean diet) after healing of myocardial infarction, percutaneous intervention, or coronary bypass (from the REasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke Study). Am J Cardiol 113: 1933-1940, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]