Abstract

The negative regulator of Rho family GTPases, p190A RhoGAP, is one of six mammalian proteins harboring so-called FF motifs. To explore the function of these and other p190A segments, we identified interacting proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Here we report that endogenous human p190A, but not its 50% identical p190B paralog, associates with all 13 eIF3 subunits and several other translational preinitiation factors. The interaction involves the first FF motif of p190A and the winged helix/PCI domain of eIF3A, is enhanced by serum stimulation and reduced by phosphatase treatment. The p190A/eIF3A interaction is unaffected by mutating phosphorylated p190A-Tyr308, but disrupted by a S296A mutation, targeting the only other known phosphorylated residue in the first FF domain. The p190A-eIF3 complex is distinct from eIF3 complexes containing S6K1 or mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and appears to represent an incomplete preinitiation complex lacking several subunits. Based on these findings we propose that p190A may affect protein translation by controlling the assembly of functional preinitiation complexes. Whether such a role helps to explain why, unique among the large family of RhoGAPs, p190A exhibits a significantly increased mutation rate in cancer remains to be determined.

Keywords: cell biology, GTPase activating protein (GAP), mass spectrometry (MS), Rho (Rho GTPase), translation initiation factor, protein biosynthesis, protein complexes, protein domains, translation ini, translational initiation

Introduction

Members of the Rho GTPase family act as binary switches to control many cell biological processes. They perform this function by cycling between GTP-bound “on” and GDP-bound “off” states. Proteins that regulate this cycling include guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs),3 which activate Rho family members by eluting Rho-bound GDP and replacing it with the more abundant GTP, and by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs), which enhance the low intrinsic GTPase activity of Rho family members, causing their inactivation. In their GTP-bound active state Rho family members are capable of interacting with a diverse set of effector proteins, which mediate their various effects (1, 2).

Remarkably, the human genome includes 68 genes encoding RhoGAP-like proteins (2, 3). Among the first discovered, p190A RhoGAP (encoded by the ARHGAP35 gene and hereafter referred to as p190A) was identified as a tyrosine-phosphorylated 190-kDa protein that forms a complex with p120 RasGAP in Src-transformed or growth factor-stimulated cells (4–6). The 1499-residue human p190A protein includes an N-terminal GTPase-like segment, followed by four so-called FF domains (7), and a C-terminal RhoGAP catalytic region (8). No recognized motifs map to the ∼700 amino acids between the FF domain array and the RhoGAP segment, but parts of this region have been implicated in p120 RasGAP binding, in the regulation of RhoGAP substrate specificity and activity (9, 10) and, together with two adjacent FF domains, in controlling the functionally important localization of p190A to F-actin protrusions (11). Interestingly, a survey of somatic mutations in 4,742 exome sequences from 21 tumor types identified ARHGAP35 as a novel, highly significantly mutated gene in 15% of endometrial cancers, as well as in 2% of the total tumor cohort (12). This finding was in line with earlier reports that had implicated p190A as a potential tumor suppressor (13–15).

Conserved from yeast to mammals, FF domains are ∼60 amino acid protein-protein interaction motifs characterized by two conserved phenylalanine residues (7). Arrays of FF domains are found in just six human proteins, namely in the TCERG1 and TCERG1L transcription elongation regulators, in the PRPF40A and PRPF40B splicing factors, and in the ∼50% identical p190A and p190B RhoGAP proteins. Others previously found that p190A interacts with the serum-inducible transcription factor TFII-I via its first FF domains, and that this interaction is disrupted upon PDGF-stimulated phosphorylation of Tyr-308 within this protein segment (16). However, whether growth factor regulated cytoplasmic sequestration of TFII-I is the only function of p190A FF domains is called into question by the fact that zebrafish, Drosophila melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans p190 RhoGAP orthologs include similar FF domain arrays, but lack obvious TFII-I orthologs. Thus, to shed further light on the functions of this and other p190A segments, we set out to identify proteins associated with endogenous human p190A. Here we report our unexpected finding that p190A, but not its 50% identical p190B paralog, interacts with eIF3A and exists in a complex with several other translational preinitiation complex subunits. We mapped the interacting segments to an N-terminal p190A region that includes the first FF domain, and to the winged helix-fold of the eIF3A PCI (Proteasome, COP9 signalosome, eIF3) domain. The interaction between p190A and eIF3A is stable and unlike the p190A/TFII-I interaction, unaffected by mutating Tyr308. However, a non-phosphorylatable S296A, but not a phosphomimicking S296D mutation, targeting the only other known phosphorylated residue in the first FF domain, disrupts the interaction, which together with other evidence argues that the interaction between p190A and eIF3A is regulated by phosphorylation. Because some functionally important preinitiation complex subunits are missing from the detected complex, we propose a role for p190A in translational regulation, by controlling the assembly of functional preinitiation complexes.

Results

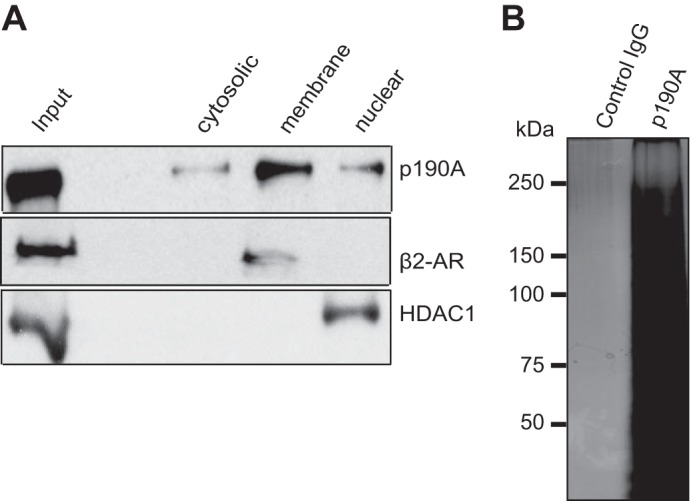

Proteomic Identification of p190A-associated Proteins

In HeLa cell extracts fractionated by differential centrifugation, p190A predominantly resides in the detergent-soluble membrane fraction, with some protein also found in the nuclear pellet and cytosol (Fig. 1A). A similar distribution was previously reported for Rat-1 fibroblast p190A (6). To identify proteins associated with endogenous p190A, we used a p190A antibody affinity matrix to purify potential complexes from the detergent-soluble membrane fraction of serum-starved and growth factor-stimulated HeLa cells, using a non-immune IgG affinity matrix as a control. After extensive washing, bound proteins were eluted, size fractionated by SDS-gel electrophoresis, and visualized by silver staining. In both growth factor-stimulated and serum-starved samples, a complex mixture of proteins was eluted from the p190A but not the control matrix (shown for the growth factor-stimulated sample in Fig. 1B). For identification the affinity-enriched and SDS-PAGE-fractionated proteins were subjected to analysis by microcapillary liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Remarkably, the 20 identified proteins with the highest number of MS/MS spectra (spectral counts) include p190A/ARHGAP35 itself and 14 translation preinitiation complex subunits (17), including 11 of the 13 eIF3 subunits (18), two eIF4F subunits (eIF4A1 and eIF4G1), and poly(A)-binding protein PABPC1 (Table 1). No previously reported p190A/ARHGAP35 interacting proteins are among the top 20 identified proteins, whereas supplemental Table S1, listing 230 proteins with at least two spectral counts in either sample, includes δ-catenin/CTNND1 (19), present in both growth factor-stimulated and serum-starved samples, and p120 RasGAP/RASA1, represented by three unique peptides in the growth factor-stimulated sample. Of note, whereas the spectral counts for p190A itself were similar in growth factor-stimulated and serum-starved samples, most other proteins were more abundant in the former (Table 1 and supplemental Table S1), suggesting that serum stimulation enhances the interaction between p190A and its associated proteins.

FIGURE 1.

Subcellular localization of p190A RhoGAP and affinity purification of associated proteins. A, in HeLa cell fractions prepared by differential centrifugation, most p190A was found in the detergent-soluble membrane fraction. β2-Adrenergic receptor (β2-AR) and HDAC1 antibodies were used to monitor fraction purity. Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane (B). Silver-stained gel, showing that multiple proteins eluted from an anti-p190A affinity matrix did not interact with a non-immune IgG affinity matrix. The samples represent growth factor-stimulated cells. Essentially identical results were obtained when an extract of serum-starved HeLa cells was similarly analyzed (not shown).

TABLE 1.

Multiple translation preinitiation complex subunits are among the 20 most abundant proteins associated with membrane-associated p190A

Shown are gene symbols, locus IDs, and spectral counts (SC) observed in serum-starved and growth factor-stimulated samples.

| UniProt ID | Gene | Gene ID | SC starved | SC stimulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q14152 | EIF3A | 8661 | 128 | 172 |

| P55884–2 | EIF3B | 8662 | 92 | 141 |

| Q04637–3 | EIF4G1 | 1981 | 80 | 128 |

| Q99613 | EIF3C | 8663 | 84 | 117 |

| Q9Y262 | EIF3L | 51386 | 71 | 99 |

| P60228 | EIF3E | 3646 | 47 | 81 |

| O15371 | EIF3D | 8664 | 38 | 68 |

| O00303 | EIF3F | 8665 | 32 | 73 |

| Q7L2H7 | EIF3M | 10480 | 32 | 69 |

| O15372 | EIF3H | 8667 | 30 | 67 |

| Q9NRY4–2 | ARHGAP35 | 2909 | 45 | 52 |

| Q5JSZ5 | PRRC2B | 84726 | 40 | 56 |

| O75821 | EIF3G | 8666 | 26 | 61 |

| P11940–2 | PABPC1 | 26986 | 30 | 50 |

| Q13347 | EIF3I | 8668 | 30 | 50 |

| Q8IVT2 | MISP | 126353 | 24 | 49 |

| P07437 | TUBB | 203068 | 19 | 37 |

| P60842 | EIF4A1 | 1973 | 12 | 40 |

| P60709 | ACTB | 60 | 11 | 40 |

| P49792 | RANBP2 | 5903 | 16 | 29 |

To determine whether a complex between p190A and translation initiation factors is also detectable in unfractionated HeLa extracts, we performed a second proteomic analysis. In this analysis, performed without SDS-PAGE size fractionation of affinity-enriched proteins, a largely overlapping set of translation preinitiation factors, including 12 eIF3 subunits, was detected, although in this case only eIF3A and eIF3B ranked among the top 35 p190A-associated proteins (supplemental Table S2).

The fact that both proteomic experiments detected all but one or two eIF3 subunits suggests that p190A associates with the eIF3 complex, which serves as a scaffold for larger preinitiation complexes involved in mRNA 5′-cap binding and in the scanning mechanism responsible for identifying the correct translational start codon (18). The presence of PABPC1 and eIF4F subunits eIF4A1 and eIF4G1 also implicates such a p190A-containing complex in the initiation of mRNA translation. Further supporting this idea, supplemental Table S1 includes the two remaining eIF3 subunits (eIF3J and eIF3K), the remaining eIF4F subunit (eIF4E; the mRNA cap-binding protein), two paralogs of eIF4A1 (eIF4A2 and eIF4A3), the PABPC1 paralog PABPC4, and 40S small ribosome subunit proteins RPSA, RPS3, RPS3A, RPS8, RPS14, RPS18, RPS19, and RPS25. Finally, PRRC2C (proline-rich coiled-coil 2C), a member of the mRNA interactome (20) was found associated with eIF3A, eIF3E, eIF3F, eIF3H, and eIF3I in previous proteomic studies (21–24).

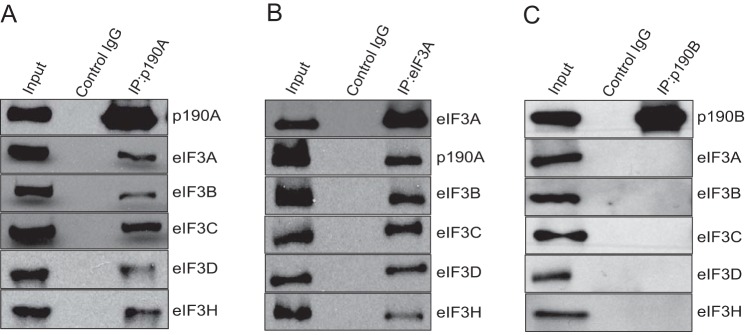

Confirmation of the p190A/eIF3 Association

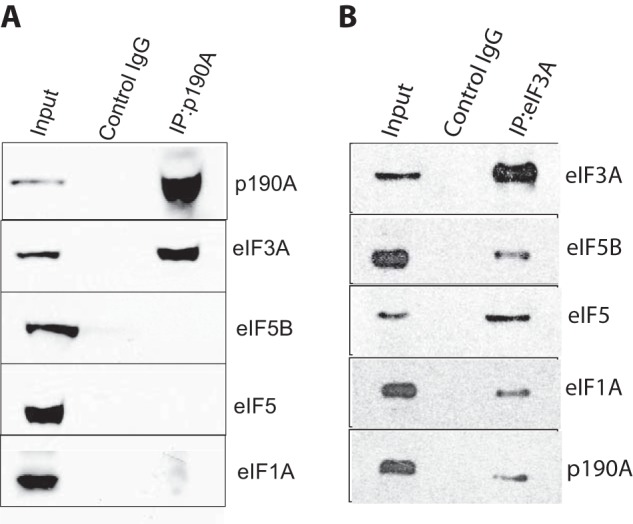

To rule out an obvious artifact, we tested whether the rabbit polyclonal antibody used to affinity purify p190A complexes cross-reacts with one or more translation factors. To rule this out, we used a mouse monoclonal antibody to precipitate p190A from HeLa cells, and analyzed the presence of eIF3A, eIF3B, eIF3C, eIF3D, and eIF3H by immunoblotting. In this and additional co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments we also increased the stringency of washes by using ionic detergent containing RIPA rather than Triton buffers. Under these more stringent conditions all five tested eIF3 subunits again co-precipitated with p190A (Fig. 2A). Moreover, p190A, eIF3B, eIF3C, eIF3D, and eIF3H each co-precipitated with eIF3A (Fig. 2B). Translational preinitiation complexes include the 40S small ribosomal subunit and bind to the 5′ cap of mRNAs to initiate translation (17). However, RNase treatment did not affect the co-precipitation of p190A and the above five eIF3 subunits, arguing that complex formation does not require RNA (not shown). Arguing that the detected interaction is specific for p190A, no association between the five tested eIF3 subunits and endogenous p190B RhoGAP was detected in similar co-IP experiments (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

eIF3 subunits co-precipitate with p190A, and vice versa. A, five endogenous HeLa cell eIF3 subunits co-immunoprecipitate with endogenous p190A. B, p190A, eIF3B, eIF3C, eIF3F, and eIF3H co-precipitate with eIF3A. C, endogenous p190B precipitated from HeLa cells does not detectably associate with the five tested eIF3 subunits.

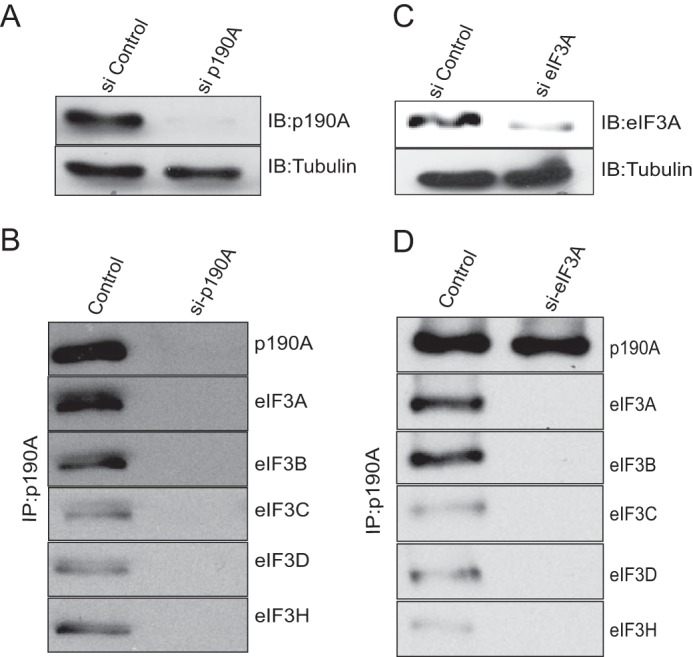

Because a role for p190A in translational initiation was unanticipated, we performed a further specificity test by repeating the co-IP experiments with HeLa cells in which either p190A or eIF3A had been knocked down. Using ON-TARGETplus siRNA Smartpools, near complete knockdown of p190A and substantial knockdown of eIF3A was achieved (Fig. 3, A and C). In cells lacking p190A, the p190A antibody did not co-IP any of the five analyzed eIF3 subunits, and vice versa, p190A and the four other eIF3 subunits were not precipitated by the eIF3A antibody when eIF3A was knocked down (Fig. 3, B and D). The latter observation is compatible with the recent finding that eIF3A knockdown disintegrates the entire eIF3 complex (25). Taken together, these results provide strong evidence that the detected interaction occurs in vivo.

FIGURE 3.

Co-precipitation of p190A and eIF3 subunits is prevented by knockdown of eIF3A or p190A. HeLa cells were transfected with a siRNA control, or with p190A (panels A and B) or eIF3A (panels C and D) siRNA Smartpools. After transfection cells were cultured for 72 h prior to lysis and processing for immunoprecipitation. Panels A and C show the levels of p190A or eIF3A knockdown achieved. Panels B and D show that p190A or eIF3A knockdown prevents the co-precipitation of the proteins indicated to the right. The control lanes in panels B and D show p190A co-precipitation of the indicated eIF3 subunits from untreated HeLa cells.

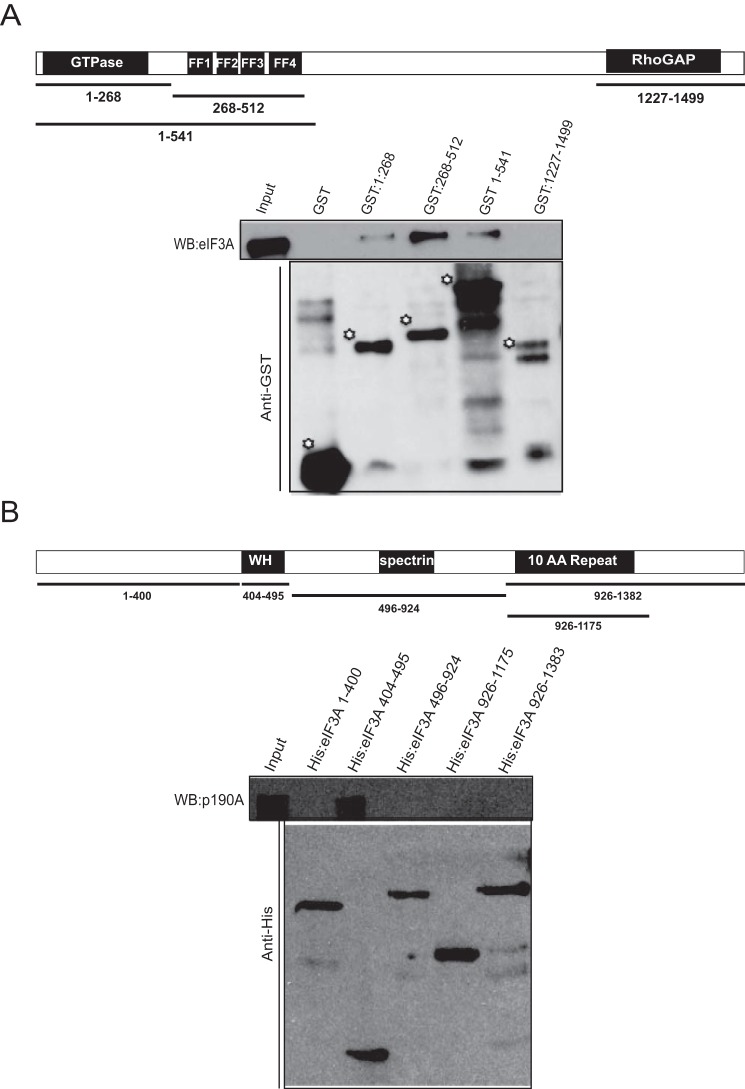

p190A Interacts with eIF3A: Mapping of the Responsible Domains

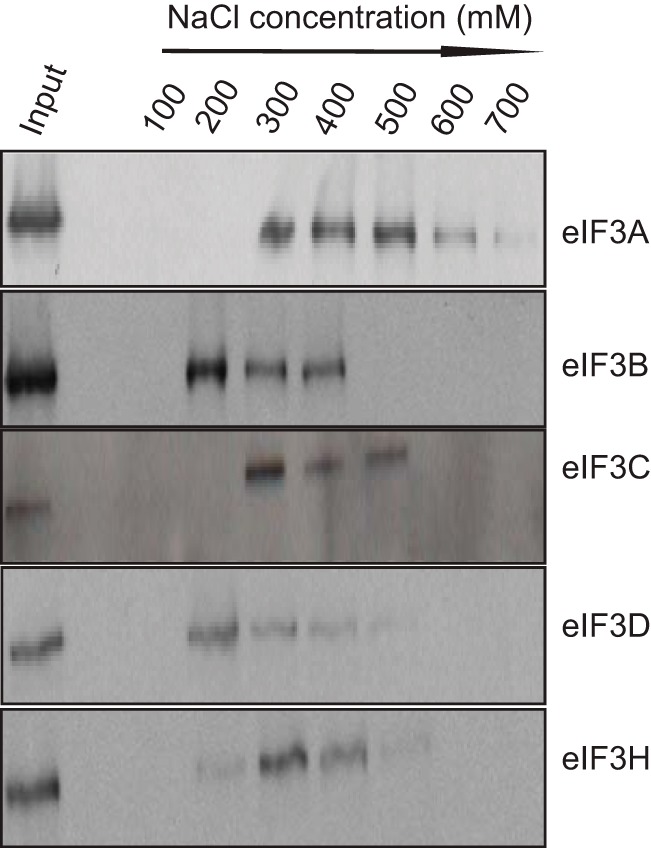

Because the 20 proteins with the highest number of spectral counts in Table 1 include 11 of 13 eIF3 subunits, we speculated that p190A might interact with one or more subunits of this complex. As a first test, we analyzed the stability of the interaction between p190A and eIF3A, eIF3B, eIF3C, eIF3D, and eIF3H by subjecting p190A immune complexes to washes of increasing ionic strength. Fig. 4 shows that among the five subunits analyzed, the interaction between p190A and the eIF3A scaffolding subunit of the eIF3 functional core (26) is most stable, with some interaction detectable even after 0.6 m NaCl RIPA buffer washes. Retention of eIF3A in p190A immune complexes even after removal of other eIF3 subunits suggests it may represent a key interface for p190A/eIF3 interaction. Consistent with this interpretation, RNAi knockdown of eIF3A abolished the interaction of p190A with four other eIF3 subunits (Fig. 3D). To obtain more direct evidence that p190A associates with eIF3A, and to map the interacting protein domains, we performed pulldown experiments with GST fusion proteins representing various p190A segments (Fig. 5A). In these assays, eIF3A was brought down by a GST fusion protein representing the p190A N-terminal GTPase domain, and more strongly by a protein representing the adjacent FF domains. However, eIF3A did not detectably interact with a fusion protein representing the RhoGAP domain, or with GST itself (Fig. 5A). In similar experiments with His-tagged eIF3A fusion proteins, p190A interacted with an eIF3A fusion protein that included the winged helix-fold (27) of its PCI domain (residues 404–495), but not with fusion proteins representing other parts of the protein (Fig. 5B). Although these results do not rule out that other translation factors contribute to the detected interaction, they do suggest that an interaction between the N-terminal p190A GTPase/FF domain segment and the eIF3A PCI domain winged helix-fold plays an important role.

FIGURE 4.

Among five tested eIF3 subunits, the p190A-eIF3A co-precipitation is most resistant to increased ionic strength. HeLa cell extracts were prepared by lysing cells in 50 mm NaCl containing RIPA buffer. p190A immunoprecipitates collected on Protein A-Sepharose beads were washed with 0.2 ml of RIPA buffer of the indicated ionic strengths, after which 50 μl of the washes were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

FIGURE 5.

Mapping of the p190A and eIF3A interacting segments. The indicated segments of p190A (diagram in panel A) and eIF3A (panel B) were produced as GST fusion proteins. The central region of p190A could not be made as a soluble fusion protein and has not been analyzed. The anti-GST or anti-His tag blots in panels A and B show the sizes and relative amounts of GST proteins used in the pull downs. The eIF3A Western blot (WB) in panel A show that eIF3A interacts weakly with the p190A GTPase domain (residues 1–268), and more strongly with a fusion protein representing all four FF domains (residues 268–512). Interaction is also observed with a fusion protein representing p190A residues 1–512. The p190A Western blot in panel B shows that only the winged helix (WH) segment of the eIF3A PCI domain interacts with p190A in this assay.

Nucleotide Binding to the p190A GTPase Domain Is Not Required for eIF3A Binding

The N-terminal GTPase domain of p190A binds GTP, and although two guanine nucleotide-binding deficient S36N or 201KCD203 to 201DCV203 mutants both retained in vitro RhoGAP activity (8, 28), the former mutant lacked obvious in vivo activity when expressed in NIH 3T3 cells (28). Because eIF3A interacts with an N-terminal p190A segment that includes the GTPase domain, we tested whether the ability to bind nucleotide affects eIF3A binding. To this end we introduced the previously characterized 201DCV203 double mutation in our p190A1–512-GST fusion construct, and analyzed its ability to pulldown eIF3A. Suggesting that nucleotide binding is not required for eIF3A binding in this setting, no difference in the amount of eIF3A pulled down by the wild-type and mutant GST proteins was observed (Fig. 6A).

FIGURE 6.

Further characterization of the p190A/eIF3A interaction. A, similar amounts of eIF3A are pulled down by wild-type and nucleotide binding defective GST-p190A1–512 fusion proteins. The anti-GST blot shows that similar amounts of fusion protein were used in the pull downs. B, GST pulldown showing that eIF3A specifically interacts with a fusion protein representing the first p190A FF domain. The protein segments represented by the four indicated GST fusion proteins are documented under “Experimental Procedures.” C, the amount of eIF3A that co-precipitated with N terminally HA-tagged full-length p190A (lane 3) is reduced by prior λ-phosphatase treatment (lane 4). Addition of a phosphatase inhibitor partially prevented this reduction (lane 5). Lane 1 shows input proteins; lane 2 is empty. D, quantification of the amount of eIF3A co-precipitating with HA-p190A. Shown is the average band intensity of three biological replicates. Error bars indicate S.D. Column numbers refer to the conditions specified in panel C.

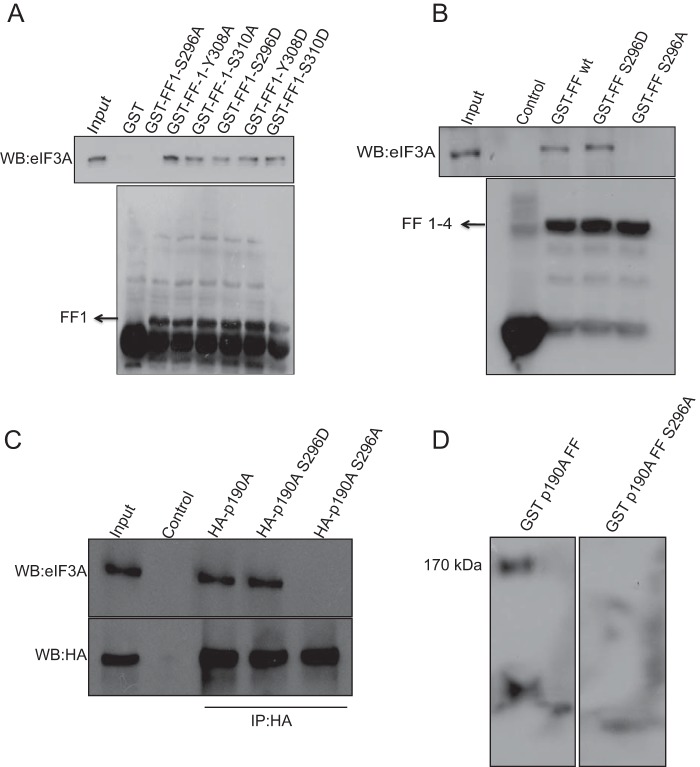

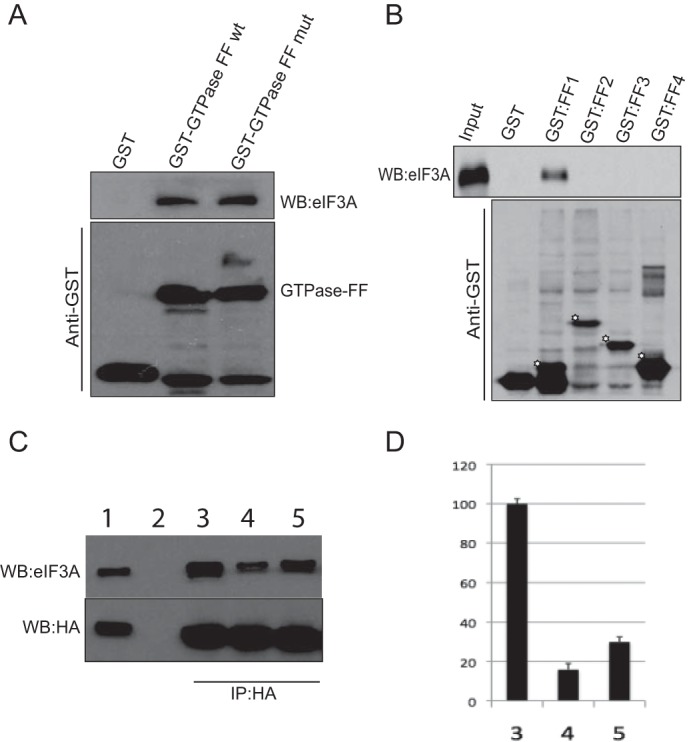

The First FF Domain of p190A Binds eIF3A

Next, we analyzed which of the four FF domains are required for eIF3A binding. As shown in Fig. 6B, of four GST proteins that each cover a single FF domain, only the one representing the first such domain brought down eIF3A. This first FF domain includes Tyr308, whose PDGF-stimulated phosphorylation was previously found to disrupt an interaction with transcription factor TFII-I (16). For this reason, and because growth factor stimulation appeared to cause an increase in the amount of several proteins associated with p190A (Table 1 and supplemental Table S1), we analyzed whether λ-phosphatase treatment of HeLa extracts prior to immunoprecipitation affected the p190A-eIF3A association. Arguing that phosphorylation of one or both proteins enhances their interaction, the amount of eIF3A co-precipitating with p190A was reduced by phosphatase treatment. The addition of a phosphatase inhibitor mixture partially, but reproducibly, prevented this reduction (Fig. 6, C and D).

A p190A S296A Mutation Abolishes the Interaction with eIF3A

The interaction between p190A and TFII-I is disrupted by growth factor-stimulated Tyr308 phosphorylation (16). However, non-phosphorylatable Y308A and phosphomimetic Y308D mutants of the p190A272–324-GST fusion protein representing the first FF domain, showed little difference in their ability to pulldown p190A (Fig. 7A). The only other p190A first FF domain residue identified as phosphorylated in the PhosphoSitePlus database is evolutionary conserved Ser296. Arguing that phosphorylation of Ser296 may enhance the interaction between p190A and eIF3A, a S296D phosphomimicking mutant retained the ability to pulldown eIF3A. However, this ability was abolished by S296A substitutions, either in the context of GST-FF1 or larger GST-FF1–4 fusion proteins (Fig. 7, A and B). To analyze whether Ser296 also affects the interaction between eIF3A and full-length p190A, we introduced the S296A and S296D mutations in full-length N terminally double HA-tagged transgenes. When an anti-HA antibody was used to precipitate these proteins from HeLa cells, the wild-type and S296D mutant proteins co-precipitated similar amounts of eIF3A, whereas no detectable eIF3A co-IPed with the S296A mutant (Fig. 7C). Finally, suggesting that p190A directly interacts with eIF3A, probing a blot of size fractionated HeLa proteins with a wild-type or S296A mutant p190A272–324-GST fusion protein, followed by detection of bound proteins with an anti-GST antibody, detected a 170-kDa protein (the size of eIF3A) with the wild-type but not with the mutant probe (Fig. 7D). The wild-type probe was also detected a smaller protein the identity of which remains unknown, but which may represent an eIF3A degradation product or one of the other five PCI domain-containing eIF3 subunits. Thus, we conclude that a single in vivo phosphorylated serine residue in the first FF domain plays an important role in promoting the interaction of p190A and eIF3A.

FIGURE 7.

Missense mutations of first FF domain residues differentially affect eIF3A interactions. A, Ser296 and Tyr308 are the only known phosphorylated residues in the first FF domain. Phosphomimicking S/D or Y/D and non-phosphorylatable S/A or Y/A missense mutations of Ser296 or Tyr308, as well as of an adjacent Tyr310 residue were generated in the context of the GST-FF1 fusion protein and used to pull down eIF3A. The S296A mutant fusion protein was the only one that did not interact with eIF3A. B, the S296A missense mutation in the context of the GST-FF1–4 (residues 268–512) fusion protein also prevented the pull down of eIF3A. C, eIF3A co-precipitates with full-length wild-type and S296D p190A, but not with S296A p190. N terminally HA-tagged p190A vectors were transfected in HeLa cells, and proteins were precipitated using an anti-HA monoclonal antibody. D, blots of size-fractionated HeLa cell lysates were sequentially probed with wild-type or S296A mutant GST-FF1 fusion proteins, and with an anti-GST antibody. The band labeled eIF3A detected by the wild-type but not by the mutant probe is of the size expected for eIF3A. WB, Western blot.

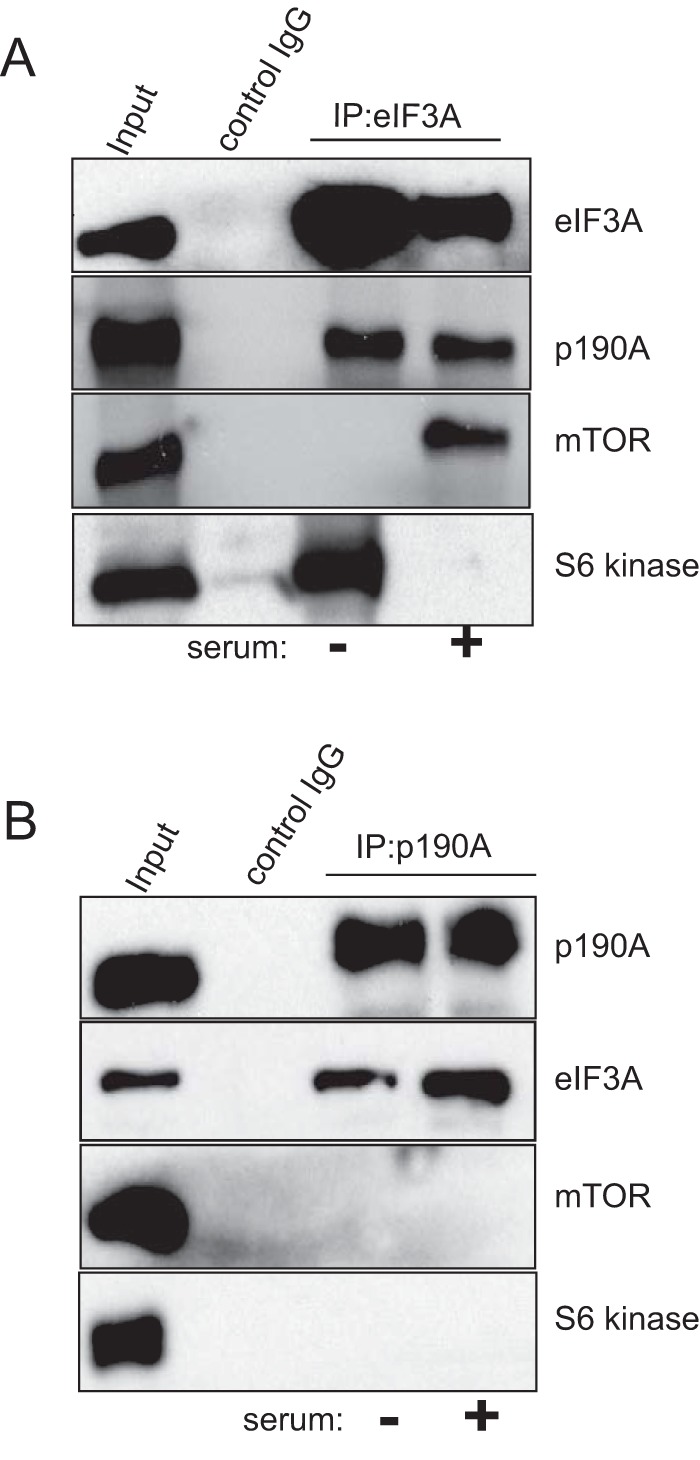

p190A-containing eIF3A Complexes Do Not Contain S6K1 or mTOR

Others previously found that p70 S6 kinase (S6K1) associates with the eIF3 complex in serum-starved cells, whereas an mTOR·Raptor·eIF3 complex was detectable upon serum stimulation (29). Using co-IP, we confirmed the mutually exclusive serum-controlled interactions between eIF3A and S6K1 or mTOR (Fig. 8A). We then tested whether p190A was part of either the eIF3·S6K1 or eIF3·mTOR complex. Not surprising, given that no S6K1 or mTOR peptides were seen in our proteomic analyses, no interaction between S6K1 or mTOR and p190A was evident (Fig. 8B). Thus, eIF3 complexes containing S6K1, mTOR·Raptor, and p190A RhoGAP appear mutually exclusive.

FIGURE 8.

p190A, mTOR, and S6 kinase form distinct complexes with eIF3A. The input lanes in both panels show blots of cell lysates probed with the antisera indicated on the right. The lanes labeled “control IgG” show that eIF3A, p190A, mTOR, or S6 kinase are not precipitated by a non-immune antibody. Panel A shows that p190A co-IPs with eIF3A in both serum-starved and -stimulated cells, whereas mTOR and S6 kinase show reciprocal interactions with eIF3A, as previously reported. Panel B shows that unlike eIF3A, mTOR and S6 kinase do not co-precipitate with p190A in either serum-starved or -stimulated cells.

p190A May Control the Assembly of Functional Preinitiation Complexes

The regulation of eukaryotic mRNA translation occurs mainly at the rate-limiting initiation step, which involves binding of a 43S preinitiation complex, consisting of the 40S small ribosomal subunit and eukaryotic initiation factor complexes that include eIF3, eIF4F, and the eIF2-GTP·Met-tRNA ternary complex, to the mRNA 5′-end m7GpppN cap structure. Subsequently, with the help of additional factors, the 43S complex scans along the 5′-untranslated region (5′-UTR) to locate the initiation codon. Upon interacting with this codon, eIF5-stimulated GTP hydrolysis of the eIF2-GTP·Met-tRNA complex results in preinitiation complex dissociation, allowing the joining of the 60S ribosomal subunit to form an 80S ribosome poised for translational initiation (30). Suggesting that p190A may prevent the assembly of functional 43S preinitiation complexes, although the p190A-associated proteins identified include all subunits of the eIF3 and eIF4F complexes, no peptides representing several other functionally important subunits were detected. Thus, peptides representing eIF1, eIF1A, all three subunits of the eIF2 complex (eIF2S1, eIF2S2, and eIF2S3), eIF4B, eIF5, and eIF5B are absent from supplemental Table S1, although some of these proteins are included as low spectral count, low confidence interactors in the more extensive list (supplemental Table 2) of potential p190A-associated proteins detected in our second proteomic analysis. For three of the above proteins (eIF1A, eIF5, and eIF5B) we confirmed co-IP with eiF3A, but not with p190A (Fig. 9). We hypothesize, because p190A interacts with the winged helix/PCI domain of eIF3A, and because cryoelectron microscopy suggests that a horseshoe-like arrangement of the PCI domains of the six PCI domain containing eIF3 subunits represents a major protein-protein interaction interface of the eIF3 core complex (31, 32), that p190A may control the rate of mRNA translation by controlling the assembly of functional 43S preinitiation complexes. Additional work is required to test the merits of this idea.

FIGURE 9.

Not all preinitiation complex subunits co-precipitate with p190A. A, eiF3A co-precipitates with p190A, but eIF5, eIF5B, and eIF1A do not. B, all indicated proteins co-precipitate with eIF3A.

Discussion

By functioning as molecular on/off switches, Rho family GTPases play important roles in multiple cell biological processes, including cell migration, endocytosis, and cytokinesis (2). Given the importance of RhoA-C, Rac1–3, Cdc42, and other Rho family members in cell biology, it may not be surprising that they are subject to intricate regulation. This is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that the human genome includes 68 genes encoding RhoGAP-like proteins, and an even larger number or genes predicting RhoGEFs (2, 33, 34). Many of these proteins contain a variety of protein and/or lipid interaction motifs, the significance of which remains largely unexplored. This is what motivated the proteomic analysis of p190A RhoGAP reported here.

Our finding that endogenous HeLa cell p190A associates with multiple translational preinitiation complex subunits was unexpected, given that no previous evidence had suggested a role for p190A or its GTPase substrates in the rate-limiting initiation step of mRNA translation. However, our finding that the first FF domain of p190A interacts with the winged helix/PCI domain of eIF3A, and our identification of p190A Ser296 as an in vivo phosphorylated residue required for this interaction, clearly implicates p190A in this process. Mechanistically, p190A might serve as an eIF3 anchoring protein that directs the localized translation of mRNAs. Alternatively, by preventing the assembly of complete preinitiation complexes, p190A might affect the overall rate of mRNA translation. Our results suggest the latter, given that eIF1, eIF1A, and other important translational preinitiation complex subunits appear to be missing from the p190A complex. Suggestive evidence that the p190A/eIF3A interaction is enhanced by phosphorylation argues that the translation-related role of p190A may be regulated by upstream signals. However, the sequence around Ser296 does not resemble any consensus phosphorylation site and no candidate protein kinase that might target this residue was suggested upon analysis of the human p190A sequence with the Scansite-3 algorithm.

Unlike p190A, its closely related p190B paralog does not interact with eIF3 subunits. The specificity of the p190A/eIF3A interaction is further underscored by the fact that the interaction between full-length p190A and eIF3A is abolished by a p190A-S296A missense mutation. Ser296 is conserved in human p190B and Drosophila p190, but whether this residue is phosphorylated in these proteins is not known. Although p190A-Ser296 phosphorylation was detected in a global phosphoproteomic study (35), it remains unknown whether Ser296 phosphorylation changes upon serum stimulation. We note that the FF domain-mediated interaction between transcription elongation factor TCERG1 and the C-terminal domain of the largest RNA polymerase II subunit requires phosphorylation of C-terminal domain serine residues, leading to the notion that FF domains are phosphoserine binding motifs (36, 37). The human eIF3A PCI domain GST fusion protein that binds p190A spans residues 404–495, and although none of the 29 phosphorylation sites identified in a proteomic analysis of the human eIF3 complex fall within this region (38), two global phosphoproteome studies identified eIF3A PCI domain residue Ser492 as being phosphorylated (39, 40). Whether phosphorylation of this residue affects the interaction between eIF3A and p190A is worth exploring.

Two proteins with canonical roles in translational control, S6K1 and mTOR, associate with the eIF3 complex in a mutually exclusive manner. Thus, in serum-starved cells, inactive S6K1 associates with the eIF3 complex, whereas stimulation of cells with a variety of factors leads to the formation of an eIF3 complex containing mTORC1 subunits mTOR and Raptor. Subsequent mTORC1-mediated activation of S6K1 causes the latter protein to dissociate and phosphorylate eIF4B (29), among other targets. More recent analyses implicated eIF3F as the eIF3 subunit responsible for both mTOR and S6K1 binding (41, 42). Because p190A·eIF3 complex formation involves the eIF3A subunit, it is conceivable that eIF3 simultaneously interacts with p190A and S6K1 or mTOR. However, our proteomic analysis did not detect S6K1 or mTORC1 subunit peptides, and S6K1 or mTOR did not co-precipitate with p190A, suggesting that eIF3 forms distinct complexes with p190A, S6K1, or mTOR.

Others previously reported that ∼20% of eIF3A associates with endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membranes, with the remainder of the protein localized in the cytosol (43). If p190A preferentially interacts with membrane-bound eIF3A, this would explain why eIF3 subunits and other preinitiation complex proteins had especially high spectral counts in our proteomic analysis of membrane-associated p190A, compared with our similar analysis of unfractionated HeLa cell extracts (compare supplemental Tables S1 and S2).

One final issue raised by our work is whether an additional translational function explains why a recent exome sequencing survey of 4742 human cancers of 21 distinct types identified the p190A encoding ARHGAP35 gene as the only human RhoGAP gene with a significantly above background mutation rate (12). Work to test whether cancer-associated missense mutations scattered throughout the entire p190A protein differentially affect its eIF3A binding and RhoGAP activity is in progress.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Fractionation

Approximately 1 × 108 80% confluent HeLa cells were kept in serum-free DMEM for 16 h and either used directly, or stimulated with DMEM containing 20 ng/ml of EGF, IGF1, and PDGF (Sigma) for 30 min. Cells were harvested by mechanical scraping, washed 3 times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and allowed to swell in ice-cold hypotonic buffer (20 mm HEPES (pH 7.4), 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm PMSF, 2 mm Na3VO4, 10 μg/ml each of aprotinin, pepstatin, leupeptin) for 30 min. Cells were disrupted by 20–40 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer and nuclear, cytosolic, and detergent-soluble and -insoluble membrane fractions were prepared by differential centrifugation. Briefly, nuclei were collected by a 10-min spin at 1,000 × g, resuspended in hypotonic buffer, and repelleted. The supernatant was subjected to a 1-h centrifugation at 285,000 × g at 4 °C to generate cytosolic and membrane fractions. The latter was resuspended in 0.5 ml of ice-cold Triton buffer (1% Triton X-100, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm PMSF, 1 mm Na3VO4, 10 μg/ml of aprotinin, pepstatin, and leupeptin) by vigorous pipetting, vortexing, and brief sonication. After a 30-min incubation of ice, another 1-h high-speed spin generated the detergent-soluble supernatant and insoluble pellets. The latter was resuspended in 0.5 ml of Triton buffer plus 0.5% sodium deoxycholate. Cell transfection with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) followed the manufacturers protocol.

Affinity Purification and Mass Spectrometry

20 μg of affinity purified rabbit polyclonal p190A antibody (Bethyl Laboratories, number A301-736A) was coupled to 0.2 ml of protein A-Sepharose by overnight incubation in 1% (w/w) formaldehyde at 4 °C. An aliquot representing 3.5 mg of total protein of the detergent-soluble HeLa membrane fraction was added to 0.1 ml of this affinity matrix or to 0.1 ml of a similarly prepared non-immune IgG control matrix, and incubated with constant gentle agitation at 4 °C for 4 h. After six washes with Triton buffer containing 10 mm NaF and 1 mm dithiothreitol (DTT), bound proteins were eluted with 0.1 m (pH 2.0) glycine buffer, the eluate neutralized with Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and size fractionated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Coomassie-stained gel slices covering the entire molecular weight range were processed for analysis by microcapillary liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry (LC-MS2) on an LTQ Velos mass spectrometer following a standard protocol at the Harvard Medical School Taplin Mass Spectrometry Facility. The acquired MS2 spectra were searched against the human UniProt protein sequence database (downloaded 02/04/2014) supplemented with sequences of known contaminants such as porcine trypsin. The target/decoy database approach was applied to control the false discovery rate (FDR) of peptide and protein annotations. To this end the target component of the protein database was complemented with a decoy component consisting of the same protein sequences in reversed C terminus to N terminus order (44). Searching was done using the SEQUEST algorithm (45) and spectra assignments filtered to an FDR of less than 1% using a linear discriminant analysis and combined discriminant score based on the following search score and peptide sequence criteria: Xcorr, dCn, peptide length, and the number of sites missed by trypsin cleavage (46). The probability of a peptide assignment to be correct was calculated using a posterior error histogram and the probabilities for all peptides assigned to a protein were combined to filter the data set for a FDR of less than 1%. Peptides with sequences matching more than one protein in the UniProt database were assigned to the protein with most matching peptides (46). In a subsequent experiment, candidate p190A-associated proteins were similarly analyzed without prior cell fractionation. Rather than subjecting affinity enriched proteins to SDS-PAGE fractionation, proteins were reduced and alkylated in solution basically as described previously (47). Proteins were then precipitated with chloroform/methanol, resuspended in 1 m urea, 50 mm HEPES (pH 8.5), and digested using first endoproteinase LysC (Wako) and then sequencing grade trypsin (Promega). The generated peptides were analyzed by LC-MS2 in a 70-min gradient on an Orbitrap Fusion mass spectrometer equipped with an EASY-nLC 1000 autosampler/HPLC pump. The mass spectrometer was operated in a data-dependent mode with a full MS spectrum acquired in the Orbitrap followed by MS2 spectra acquired in the linear ion trap on the most abundant ions detected in the full MS spectrum. The data were essentially analyzed as described above except that the mass deviation of peptides were included into the linear discriminant analysis.

siRNA Knockdown

ON-Target plus siRNA SMART pools targeting human p190A or eIF3A (Dharmacon-Thermo Scientific) were introduced into HeLa cells using DharmaFECT transfection reagent as specified by the manufacturer. Cells were processed for analysis 72 h after transfection.

Antibodies and Immunological Procedures

For immunoprecipitations 2.5 μg of antibody was coupled to Protein A-Sepharose by overnight incubation at 4 °C. Cells were lysed in 150 mm NaCl RIPA buffer, and cell extracts containing 0.8–1.0 mg of protein were incubated with the immobilized antibody for 4 h at 4 °C, after which the beads were washed six times with RIPA buffer of the same ionic strength supplemented with 10 mm NaF and 1 mm DTT, and processed for SDS-PAGE. Immunoblotting used the following antibodies at 1:1000 dilutions: mouse p190A monoclonal (BD Transduction Laboratories number 610150), rabbit p190A polyclonal (Bethyl Laboratories, number A301-736A), eIF3A rabbit polyclonal (Cell Signaling, number 2538), affinity purified eIF3B, eIF3C, eIF3D, and eIF3H rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Bethyl Laboratories, numbers A301-760A, A300-376A, A301-758A, and A301-754A), and rabbit polyclonal anti-GST (Cell Signaling, number 2622) or anti-His-tag antibodies (Cell Signaling, number 2366). To analyze the role of phosphorylation, protein samples were incubated with λ-phosphatase (New England Biolabs) in the presence or absence of the recommended amount of the Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor Mixture (Thermo Scientific) at 30 °C for 30 min. Samples were washed six times with wash buffer prior to further processing. For quantification, films representing three experiments were scanned using an Epson Perfection V750 PRO and analyzed using ImageJ image analysis software. The eIF3A band intensities were normalized relative to HA-p190A band intensities.

Recombinant Protein Preparation and Pulldown Experiments

E. coli BL21 cells harboring GST-p190A fusion constructs were induced with 0.2 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 3 h at 37 °C and harvested by centrifugation. Bacterial pellets were sonicated in 50 mm Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm PMSF and a mixture of protein inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics). Proteins were purified on glutathione-Sepharose (Sigma) as suggested by the manufacturer. His-tagged eIF3A protein segments were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) and affinity purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen) as recommended by the manufacturer. Pulldown experiments were performed by incubating 20 μg of immobilized p190A or eIF3A proteins with 1 mg of total protein at 4 °C for 4 h. After six 1-ml 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 200 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT washes, bound proteins were eluted with 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 500 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm DTT and processed for SDS-PAGE.

Far Western Analysis

HeLa cell lysate (20 μg of protein) was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred to Immobilon PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membrane was washed with Protein Binding Buffer (PBB; 20 mm HEPES/KOH (pH 7.4), 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 10% glycerol), incubated for 3 h with PBB containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 4 °C, and probed overnight with 10 μg of affinity purified GST-p190a-FF domain fusion protein at 4 °C in 10 ml of PBB containing 5% BSA. The blot was subjected to eight 10-min 0.1% Nonidet P-40 in PBB washes, incubated with anti-GST antibody (1:1000 Cell Signaling), ECL etc.

DNA Constructs and Transfection

The N terminally HA-tagged rat p190A expression vector RcHAp190A has been described (48). RcHAp190A-S296A and RcHAp190A-S296D mutants were created by PCR mutagenesis. GST-p190A constructs were made by subcloning PCR-amplified cDNA fragments into the pGEX-KG vector, using EcoRI and XhoI. The following GST-p190A fusion constructs were generated (numbers in parentheses indicate included amino acids): GST-GTPase(1–268), GST-N terminus (1–541), GST-FF1–4(266–541), GST-FF1(272–324), GST-FF2(371–419), GST-FF3(431–480), GST-FF4(487–533), and GST-GRD(1227–1499). S296A/S296D, Y308A/Y308D, and Y310A/Y310D mutants in both the GST-FF1 and GST-FF1–4 vectors were created by PCR mutagenesis. The nucleotide-binding defective p190A GTPase double mutant has been described previously (8). His6-tagged human eIF3A constructs were made by inserting PCR-amplified cDNA fragments into the pET28a (Addgene) vector using SacI and NotI. Numbers in parentheses for the following constructs again indicate included amino acids: His-eIF3A N terminus (1–400), His-eIF3A-PCI domain (404–495), His-eIF3A-spectrin repeat (496–924), His-eIF3A-10 AA repeat (926–1175), and His-eIF3A C terminus (926–1383). The integrity of all constructs was verified by sequence analysis.

Author Contributions

A. B. conceived and coordinated the study and wrote the paper. P. P. designed, performed, and analyzed most experiments. P. M. designed the cell fractionation and initial mass spectrometry analysis. J. A. W. contributed to experiments analyzing the role of p190A in translation. B. L. and M. B. provided technical assistance. W. H. designed and coordinated the mass spectrometry analysis and helped writing the paper. All authors analyzed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jian-Ting Zhang, Indiana University School of Medicine, for the human eIF3A cDNA, Ross Tomaino, the Harvard Medical School Taplin Biological Mass Spectrometry Facility, for help with the initial proteomic analysis, Dr. Steven Gygi, Harvard Medical School, for access to the proteomics data analysis software platform, and Dr. Capucine Van Rechem for advice.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health NIGMS Grant 1R01GM087386 (to A. B.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

- GEF

- GDP/GTP exchange factor

- FF domain

- protein segment characterized by two conserved phenylalanine residues

- GAP

- GTPase activating protein

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- PBB

- phosphate binding buffer

- PCI

- proteasome, COP9 signalosome, eIF3

- PIC

- preinitiation complex

- S6K1

- ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1

- FDR

- false discovery rate

- IP

- immunoprecipitation.

References

- 1. Jaffe A. B., and Hall A. (2005) Rho GTPases: biochemistry and biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 247–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hall A. (2012) Rho family GTPases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 1378–1382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernards A. (2003) GAPs galore! a survey of putative Ras superfamily GTPase activating proteins in man and Drosophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1603, 47–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ellis C., Moran M., McCormick F., and Pawson T. (1990) Phosphorylation of GAP and GAP-associated proteins by transforming and mitogenic tyrosine kinases. Nature 343, 377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moran M. F., Polakis P., McCormick F., Pawson T., and Ellis C. (1991) Protein-tyrosine kinases regulate the phosphorylation, protein interactions, subcellular distribution, and activity of p21ras GTPase-activating protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 1804–1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Settleman J., Narasimhan V., Foster L. C., and Weinberg R. A. (1992) Molecular cloning of cDNAs encoding the GAP-associated protein p190: implications for a signaling pathway from ras to the nucleus. Cell 69, 539–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bedford M. T., and Leder P. (1999) The FF domain: a novel motif that often accompanies WW domains. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24, 264–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foster R., Hu K. Q., Shaywitz D. A., and Settleman J. (1994) p190 RhoGAP, the major RasGAP-associated protein, binds GTP directly. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 7173–7181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lévay M., Settleman J., and Ligeti E. (2009) Regulation of the substrate preference of p190RhoGAP by protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation of a phospholipid binding site. Biochemistry 48, 8615–8623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lévay M., Bartos B., and Ligeti E. (2013) p190RhoGAP has cellular RacGAP activity regulated by a polybasic region. Cell Signal. 25, 1388–1394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Binamé F., Bidaud-Meynard A., Magnan L., Piquet L., Montibus B., Chabadel A., Saltel F., Lagrée V., and Moreau V. (2016) Cancer-associated mutations in the protrusion-targeting region of p190RhoGAP impact tumor cell migration. J. Cell Biol. 214, 859–873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lawrence M. S., Stojanov P., Mermel C. H., Robinson J. T., Garraway L. A., Golub T. R., Meyerson M., Gabriel S. B., Lander E. S., and Getz G. (2014) Discovery and saturation analysis of cancer genes across 21 tumour types. Nature 505, 495–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang D. Z., Nur-E-Kamal M. S., Tikoo A., Montague W., and Maruta H. (1997) The GTPase and Rho GAP domains of p190, a tumor suppressor protein that binds the Mr 120,000 Ras GAP, independently function as anti-Ras tumor suppressors. Cancer Res. 57, 2478–2484 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kusama T., Mukai M., Endo H., Ishikawa O., Tatsuta M., Nakamura H., and Inoue M. (2006) Inactivation of Rho GTPases by p190 RhoGAP reduces human pancreatic cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Cancer Sci. 97, 848–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolf R. M., Draghi N., Liang X., Dai C., Uhrbom L., Eklöf C., Westermark B., Holland E. C., and Resh M. D. (2003) p190RhoGAP can act to inhibit PDGF-induced gliomas in mice: a putative tumor suppressor encoded on human chromosome 19q13.3. Genes Dev. 17, 476–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang W., Sordella R., Chen G. C., Hakre S., Roy A. L., and Settleman J. (2005) An FF domain-dependent protein interaction mediates a signaling pathway for growth factor-induced gene expression. Mol. Cell 17, 23–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackson R. J., Hellen C. U., and Pestova T. V. (2010) The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 113–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hinnebusch A. G. (2006) eIF3: a versatile scaffold for translation initiation complexes. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 553–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wildenberg G. A., Dohn M. R., Carnahan R. H., Davis M. A., Lobdell N. A., Settleman J., and Reynolds A. B. (2006) p120-catenin and p190RhoGAP regulate cell-cell adhesion by coordinating antagonism between Rac and Rho. Cell 127, 1027–1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Castello A., Fischer B., Eichelbaum K., Horos R., Beckmann B. M., Strein C., Davey N. E., Humphreys D. T., Preiss T., Steinmetz L. M., Krijgsveld J., and Hentze M. W. (2012) Insights into RNA biology from an atlas of mammalian mRNA-binding proteins. Cell 149, 1393–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hutchins J. R., Toyoda Y., Hegemann B., Poser I., Hériché J. K., Sykora M. M., Augsburg M., Hudecz O., Buschhorn B. A., Bulkescher J., Conrad C., Comartin D., Schleiffer A., Sarov M., Pozniakovsky A., et al. (2010) Systematic analysis of human protein complexes identifies chromosome segregation proteins. Science 328, 593–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sowa M. E., Bennett E. J., Gygi S. P., and Harper J. W. (2009) Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell 138, 389–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hein M. Y., Hubner N. C., Poser I., Cox J., Nagaraj N., Toyoda Y., Gak I. A., Weisswange I., Mansfeld J., Buchholz F., Hyman A. A., and Mann M. (2015) A human interactome in three quantitative dimensions organized by stoichiometries and abundances. Cell 163, 712–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huttlin E. L., Ting L., Bruckner R. J., Gebreab F., Gygi M. P., Szpyt J., Tam S., Zarraga G., Colby G., Baltier K., Dong R., Guarani V., Vaites L. P., Ordureau A., Rad R., et al. (2015) The BioPlex network: a systematic exploration of the human interactome. Cell 162, 425–440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wagner S., Herrmannová A., Malík R., Peclinovská L., and Valás̆ek L. S. (2014) Functional and biochemical characterization of human eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 in living cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 34, 3041–3052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Saletta F., Suryo Rahmanto Y., and Richardson D. R. (2010) The translational regulator eIF3a: the tricky eIF3 subunit!. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1806, 275–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ellisdon A. M., and Stewart M. (2012) Structural biology of the PCI-protein fold. Bioarchitecture 2, 118–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tatsis N., Lannigan D. A., and Macara I. G. (1998) The function of the p190 Rho GTPase-activating protein is controlled by its N-terminal GTP binding domain. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 34631–34638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Holz M. K., Ballif B. A., Gygi S. P., and Blenis J. (2005) mTOR and S6K1 mediate assembly of the translation preinitiation complex through dynamic protein interchange and ordered phosphorylation events. Cell 123, 569–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hinnebusch A. G. (2014) The scanning mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 83, 779–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. des Georges A., Dhote V., Kuhn L., Hellen C. U., Pestova T. V., Frank J., and Hashem Y. (2015) Structure of mammalian eIF3 in the context of the 43S preinitiation complex. Nature 525, 491–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Querol-Audi J., Sun C., Vogan J. M., Smith M. D., Gu Y., Cate J. H., and Nogales E. (2013) Architecture of human translation initiation factor 3. Structure 21, 920–928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bernards A., and Settleman J. (2005) GAPs in growth factor signalling. Growth Factors 23, 143–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bernards A., and Settleman J. (2007) GEFs in growth factor signaling. Growth Factors 25, 355–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Choudhary C., Olsen J. V., Brandts C., Cox J., Reddy P. N., Böhmer F. D., Gerke V., Schmidt-Arras D. E., Berdel W. E., Müller-Tidow C., Mann M., and Serve H. (2009) Mislocalized activation of oncogenic RTKs switches downstream signaling outcomes. Mol. Cell 36, 326–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carty S. M., Goldstrohm A. C., Suñé C., Garcia-Blanco M. A., and Greenleaf A. L. (2000) Protein-interaction modules that organize nuclear function: FF domains of CA150 bind the phosphoCTD of RNA polymerase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9015–9020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu J., Fan S., Lee C. J., Greenleaf A. L., and Zhou P. (2013) Specific interaction of the transcription elongation regulator TCERG1 with RNA polymerase II requires simultaneous phosphorylation at Ser-2, Ser-5, and Ser-7 within the carboxyl-terminal domain repeat. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 10890–10901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Damoc E., Fraser C. S., Zhou M., Videler H., Mayeur G. L., Hershey J. W., Doudna J. A., Robinson C. V., and Leary J. A. (2007) Structural characterization of the human eukaryotic initiation factor 3 protein complex by mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 1135–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mayya V., Lundgren D. H., Hwang S. I., Rezaul K., Wu L., Eng J. K., Rodionov V., and Han D. K. (2009) Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of T cell receptor signaling reveals system-wide modulation of protein-protein interactions. Sci. Signal. 2, ra46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhou H., Di Palma S., Preisinger C., Peng M., Polat A. N., Heck A. J., and Mohammed S. (2013) Toward a comprehensive characterization of a human cancer cell phosphoproteome. J. Proteome Res. 12, 260–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Harris T. E., Chi A., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Rhoads R. E., and Lawrence J. C. Jr. (2006) mTOR-dependent stimulation of the association of eIF4G and eIF3 by insulin. EMBO J. 25, 1659–1668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Csibi A., Cornille K., Leibovitch M. P., Poupon A., Tintignac L. A., Sanchez A. M., and Leibovitch S. A. (2010) The translation regulatory subunit eIF3f controls the kinase-dependent mTOR signaling required for muscle differentiation and hypertrophy in mouse. PloS One 5, e8994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pincheira R., Chen Q., Huang Z., and Zhang J. T. (2001) Two subcellular localizations of eIF3 p170 and its interaction with membrane-bound microfilaments: implications for alternative functions of p170. Eur J. Cell Biol. 80, 410–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Elias J. E., and Gygi S. P. (2007) Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat. Methods 4, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Eng J. K., McCormack A. L., and Yates J. R. (1994) An approach to correlate tandem mass spectral data of peptides with amino acid sequences in a protein database. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 5, 976–989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Huttlin E. L., Jedrychowski M. P., Elias J. E., Goswami T., Rad R., Beausoleil S. A., Villén J., Haas W., Sowa M. E., and Gygi S. P. (2010) A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell 143, 1174–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ting L., Rad R., Gygi S. P., and Haas W. (2011) MS3 eliminates ratio distortion in isobaric multiplexed quantitative proteomics. Nat. Methods 8, 937–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Settleman J., Albright C. F., Foster L. C., and Weinberg R. A. (1992) Association between GTPase activators for Rho and Ras families. Nature 359, 153–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.