Abstract

Nuclear modifier gene(s) was proposed to modulate the phenotypic expression of mitochondrial DNA mutation(s). Our previous investigations revealed that a nuclear modifier allele (A10S) in TRMU (methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridylate-methyltransferase) related to tRNA modification interacts with 12S rRNA 1555A→G mutation to cause deafness. The A10S mutation resided at a highly conserved residue of the N-terminal sequence. It was hypothesized that the A10S mutation altered the structure and function of TRMU, thereby causing mitochondrial dysfunction. Using molecular dynamics simulations, we showed that the A10S mutation introduced the Ser10 dynamic electrostatic interaction with the Lys106 residue of helix 4 within the catalytic domain of TRMU. The Western blotting analysis displayed the reduced levels of TRMU in mutant cells carrying the A10S mutation. The thermal shift assay revealed the Tm value of mutant TRMU protein, lower than that of the wild-type counterpart. The A10S mutation caused marked decreases in 2-thiouridine modification of U34 of tRNALys, tRNAGlu and tRNAGln. However, the A10S mutation mildly increased the aminoacylated efficiency of tRNAs. The altered 2-thiouridine modification worsened the impairment of mitochondrial translation associated with the m.1555A→G mutation. The defective translation resulted in the reduced activities of mitochondrial respiration chains. The respiratory deficiency caused the reduction of mitochondrial ATP production and elevated the production of reactive oxidative species. As a result, mutated TRMU worsened mitochondrial dysfunctions associated with m.1555A→G mutation, exceeding the threshold for expressing a deafness phenotype. Our findings provided new insights into the pathophysiology of maternally inherited deafness that was manifested by interaction between mtDNA mutation and nuclear modifier gene.

Keywords: hearing, mitochondrial disease, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), molecular modeling, oxygen radicals, post-translational modification (PTM), respiration, ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) (ribosomal RNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), translation

Introduction

The impairments in mitochondrial protein synthesis have been associated with both syndromic deafness (hearing loss with other medical problems such as diabetes) and nonsyndromic deafness (hearing loss is the only obvious medical problem) (1–5). Human mitochondrial translation machinery composed of 2 rRNAs and 22 tRNAs, encoded by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA),4 and more than 150 proteins (ribosomal proteins, ribosomal assembly proteins, aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, tRNA-modifying enzymes, tRNA methylating enzymes, and initiation, elongation, and termination factors), encoded by nuclear genes and imported into mitochondrion (6, 7). Mutations in LARS2, NARS2, and KARS encoding mitochondrial leucyl-tRNA synthetase, asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase, and lysyl-tRNA synthetase have been associated with deafness, respectively (8–10). The mitochondrial tRNA genes are the hot spots for deafness-associated mutations, including the tRNALeu(UUR) 3243A→G, tRNASer(UCN) 7445A→G, 7511T→C, tRNAHis 12201T→C, tRNAAsp 7551A→G, and tRNAGlu 14692A→G mutations (11–17). The m.1555A→G and m.1494C→T mutations in the 12S rRNA gene have been associated with both aminoglycoside-induced and nonsyndromic deafness in many families worldwide (3, 4, 18–20). The m.1555A→G or m.1494C→T mutation is the primary causative evident, but modifier factors including aminoglycosides or nuclear modifier genes are required for the phenotypic manifestation of these mtDNA mutations (21–26). However, the role of these nuclear modifier genes remains poorly understood.

In the previous investigations, we showed that MTO1, MSS1 (GTPBP3), or MTO2 (TRMU) genes involved in the biosynthesis of the hypermodified nucleoside 5-methyl-aminomethyl-2-thio-uridine of several mitochondrial tRNAs were the potential modifier genes for the phenotypic expression of deafness-associated 12S rRNA 1555A→G mutation (25–30). These modified uridines at the wobble positions of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln have a pivotal role in the structure and function of tRNAs, including structural stabilization, aminoacylation, and codon recognition at the decoding site of small rRNA (31–33). In particular, TRMU is the tRNA 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridylate methyltransferase responsible for the 2-thiolation of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln with mnm5s2U34 in bacteria, mcm5s2U34 in yeast, and m5s2U34 in human mitochondria (34–37). Using TRMU as a candidate gene for genotyping analysis, in combination with functional assays, we identified a nuclear modifier allele (G28T and A10S) in the TRMU gene, which interacts with the m.1555A→G mutation to cause deafness (25). The A10S mutation resided at a highly conserved residue of the N-terminal sequence of this polypeptide but did not affect importation of TRMU precursors into mitochondria (25). However, the homozygous A10S mutation caused marked decreases in the steady state levels of mitochondrial tRNAs (25). Therefore, it was anticipated that the A10S mutation affected the structure and function of TRMU, thereby altering the mitochondrial function. The effect of A10S mutation on the stability of TRMU was assessed by the Western blotting and thermal shift assays. The primary defects by the mutation appeared to be the altered biosynthesis of 5-taurinomethyl-2-thiouridine (τm5s2U) nucleotides at the wobble position of mitochondrial tRNAGln, tRNAGlu, and tRNALys (25, 34, 38). Furthermore, the deficient synthesis of s2U34 may alter the tRNA aminoacylation, because s2U34 serves as a determinant for tRNA recognition by cognate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in bacteria (39). To further investigate the effect of the TRMU A10S mutation on mitochondrial function, we examined for the levels of tRNA modification, aminoacylation of tRNAs, translation, the rates of respiration, and the production of ATP and reactive oxygen species (ROS), through use of lymphoblastoid mutant cell lines derived from Arab-Israeli control subjects and from members of an Arab-Israeli family (two subjects carrying only m.1555A→G mutation (F12H and F6D), two individuals (F20C and F8A) harboring both m.1555A→G and heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations, and two individuals (F20A and F20D) carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations) (25, 40).

Results

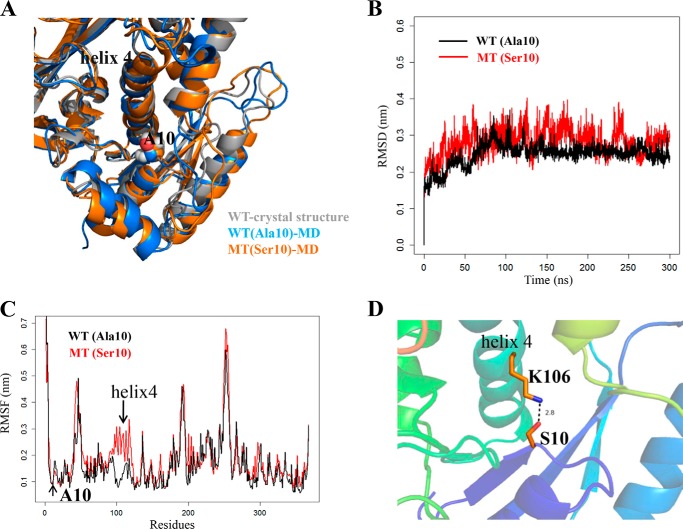

MD Simulation Analyses

We performed the molecular dynamics simulation to examine whether the A10S mutation alters the structure of TRMU (41). This method has been widely used for evaluating structural impact of diseasing-causing mutations (42). Based on the rational initial structure (43), both wild-type and mutated TRMU were evaluated by 300-ns all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. As shown in Fig. 1A, the A10S mutation did not affect the local structure around residue 10 and the overall structure of the TRMU protein. As shown in Fig. 1B, root mean square deviation curve of the mutated protein fluctuated more heavily than that of the wild-type protein, suggesting that the mutated protein exhibited unstable than its wild-type counterpart. Furthermore, we carried out root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis on the two trajectories to analyze the mobility of different regions of the protein. As shown in Fig. 1C, the RMSF around the residue 10 in the two trajectories exhibited almost same value, indicating that the A10S mutation does not affect the stability of this region. However, the RMSF values of the helix 4 (residue 98–118) in mutated protein were much higher than that of the wild-type form (Fig. 1C), suggesting that the helix 4 in mutant protein was unstable than that of wild-type protein. Both the residue 10 and the helix 4 belong to the N-terminal catalytic domain, which is located on the opposite sides within the ATP binding pocket of the protein (43). In addition, it was anticipated that the A10S mutation could introduce new interactions between the residue 10 and helix 4, which may account for the less stability of the helix 4. As shown in Fig. 1D, the hydroxyl group of Ser10 in the mutant trajectory could form the dynamic electrostatic interaction with the Lys106 residue of helix 4, whereas no interaction occurred between Ala10 and helix 4 in the wild-type trajectory. Thus, the electrostatic attraction between Ser10 and Lys106 is quite dynamic, with H-bond occupancy of only around 1%, so this dynamic interaction caused the instability to the protein but did not affect its overall 3D structure.

FIGURE 1.

MD simulations on the wild-type and mutated TRMU proteins. A, superimposition of the crystal structure (gray) with the structures of wild-type (blue) and A10S mutant (orange) proteins at the end of the simulations. B, time evolution of the root mean square deviation (RMSD) values of all Cα atoms for the wild-type (black lines) and A10S mutant (red lines) proteins. C, RMSF curves were generated from the backbone atoms for the wild-type (black lines) and A10S mutant (red lines) proteins. D, electrostatic interactions formed between Ser10 and Lys106 in the mutant protein.

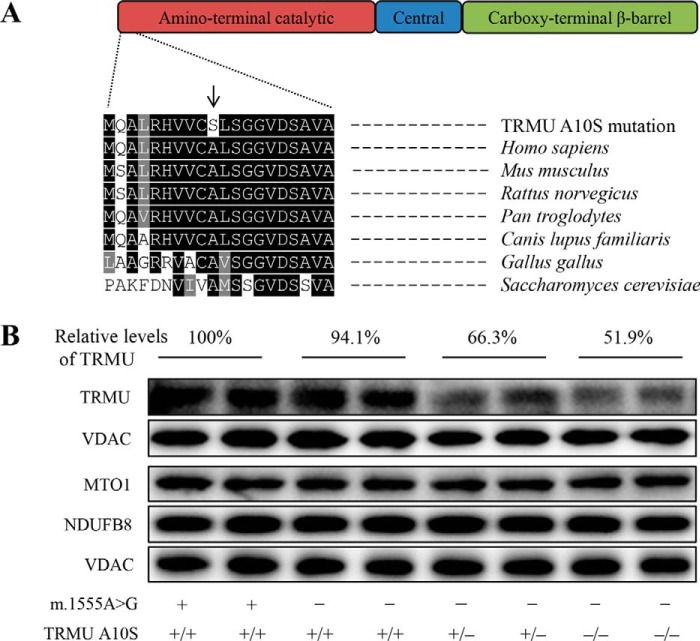

The A10S Mutation Caused the Instability of TRMU

To experimentally test the predicted effect of A10S mutation for TRMU, we analyzed the levels of TRMU by Western blotting in these mutant cell lines carrying only m.1555A→G mutation, both m.1555A→G and heterozygous or homozygous A10S mutations and two control cell lines. These blots were then hybridized with other nuclear encoding mitochondrial proteins MTO1 and NDUFB8, as well as VADC as a loading control. As shown in Fig. 2, the levels of TRMU in mutant cell lines carrying only m.1555A→G, both m.1555A→G and heterozygous or homozygous A10S mutations were 94.1, 66.3, and 51.9%, relative to the average values of control cell lines, respectively. By contrast, the levels of MTO1 and NDUFB8 in mutant cell lines were comparable with those in control cell lines. These results strongly supported the deleterious effect of A10S mutation on TRMU structure.

FIGURE 2.

The A10S mutation caused the reduced levels of TRMU. A, scheme for the multiple sequence alignment of the TRMU homologues. The position of A10S mutation is marked with an arrow. B, Western blotting analysis of six mutant and two control cell lines. 20 μg of total cellular proteins from various cell lines were electrophoresed through a denaturing polyacrylamide gel, electroblotted and hybridized with TRMU, MTO1, and NDUFB8, respectively, and with VDAC as a loading control. Quantifications of TRMU levels were determined as described elsewhere (15). The values for the mutant cell lines are expressed as percentages of the average values for the control cell lines. Cell lines harboring homozygous (−/−), heterozygous (+/−), or wild-type (+/+) TRMU mutations are indicated. Cell lines carrying the m.1555A→G (−) or wild type (+) are indicated.

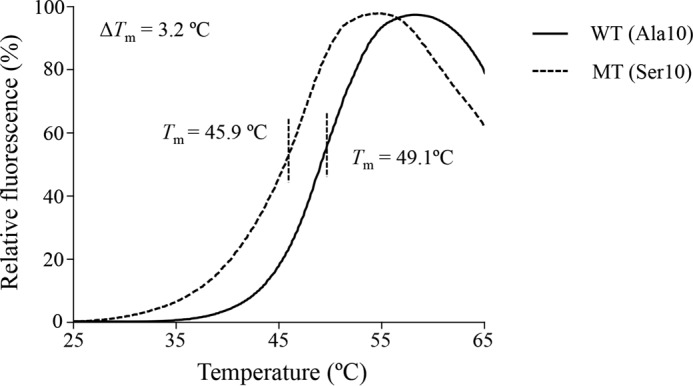

Analysis of TRMU Stability Using Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF)

The thermal stability of mutant TRMU was also assessed using the DSF, a fluorescence method that was used to monitor solution phase protein stability (44). The technique involves subjecting a protein to heat denaturation under continuous fluorescence monitoring in the presence of the environmental sensitive fluorescent dye (Thermal-shiftTM dye). We used DSF to determine the melting temperature (Tm) of TRMU, the temperature at which the concentration of folded protein is equivalent to unfolded protein. The fluorescence changes of the dye orange occurred in the presence of 1 μg of wild-type and mutated TRMU over a temperature range from 25 to 95 °C. The thermal stability of mutant protein was compared with that of wild-type protein. As shown in Fig. 3, the Tm value of wild-type TRMU was 49.1 °C, whereas the Tm value of mutant TRMU was 45.9 °C. The lower thermal stability of mutant TRMU protein than wild-type protein further supported that the A10S mutation led to the instability of TRMU protein.

FIGURE 3.

Thermal stability of wild-type and mutant TRMU. The thermal denaturation was induced heating wild-type (solid line) and mutant (dashed line) TRMU proteins from 25 to 95 °C. Relative fluorescence curves were generated with the equation (FT − Fmin)/(Fmax − Fmin), where T indicates fluorescence at temperature T, Fmin indicates the minimum fluorescence, and Fmax indicates the maximum fluorescence. ΔTm indicates the difference of Tm value between wild-type and mutant TRMU. The calculations were based on three to four determinations.

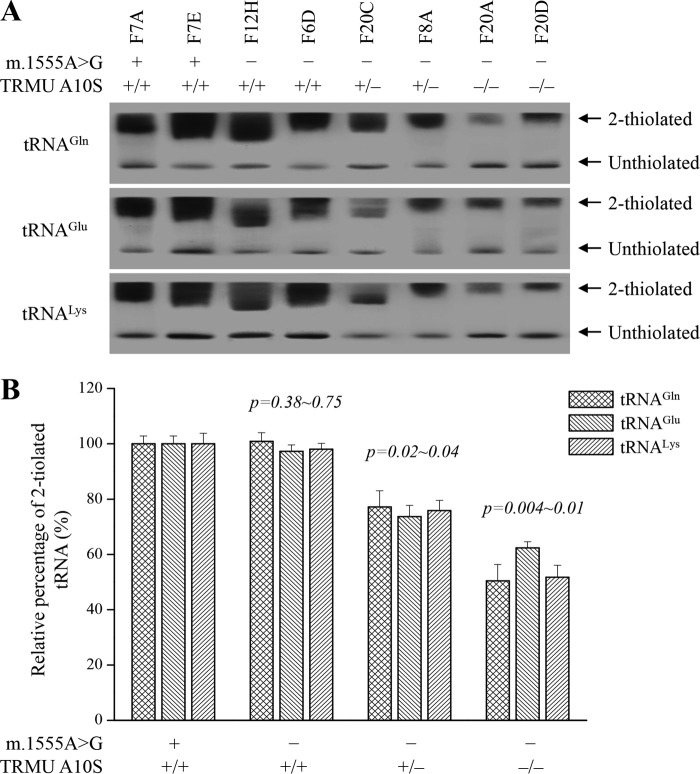

Decreases in the Thiolation of tRNAGln, tRNAGlu, and tRNALys

To further investigate whether the TRMU A10S mutation affected the 2-thiouridine modification at position 34 in tRNAs, the 2-thiouridylation levels of tRNAs were determined by isolating total mitochondrial RNAs from eight lymphoblastoid cell lines, purifying tRNAs, qualifying the 2-thiouridine modification by the retardation of electrophoresis mobility in polyacrylamide gel containing 0.05 mg/ml ((N-acryloylamino)phenyl) mercuric chloride (APM) (45–47), and hybridizing digoxingenin (DIG)-labeled probes for tRNAGln, tRNAGlu, and tRNALys. In this system, the mercuric compound can specifically interact with the tRNAs containing the thiocarbonyl group-such as tRNAGln, tRNAGlu, and tRNALys, thereby retarding tRNA migration. As shown in Fig. 4, the 2-thiouridylation levels of tRNAGln, tRNAGlu, and tRNALys were reduced significantly in mutant cells carrying the homozygous TRMU A10S mutation, compared with control cells. In particular, the 2-thiouridylation levels of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln in mutant cells carrying both homozygous A10S and m.1555A→G mutations were 52, 62, and 50%, relative to those of control cell lines, respectively. Furthermore, the 2-thiouridylation of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln in mutant cells carrying both heterozygous A10S and m.1555A→G mutations were 76, 74, and 77%, relative to those of control cells, respectively. However, the levels of 2-thiouridylation of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln in mutant cell lines carrying only m.1555A→G mutation were comparable with those in control cell lines.

FIGURE 4.

APM gel electrophoresis combined with Northern blotting of mitochondrial tRNAs. A, equal amounts (2 μg) of total mitochondrial RNAs were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis that contains 0.05 mg/ml APM and electroblotted onto a positively charged membrane and hybridized with DIG-labeled oligonucleotide probes specific for the tRNALys. The blots were then stripped and rehybridized with DIG-labeled probes for tRNAGlu and tRNAGln, respectively. The retarded bands of 2-thiolated tRNAs and non-retarded bands of tRNA without thiolation are marked by arrows. B, proportion in vivo of the 2-thiouridine modification levels of tRNAs. The proportion values for the mutant cell lines are expressed as percentages of the average values for the control cell lines. The calculations were based on three independent determinations of each tRNA in each cell line. The error bars indicate standard deviation; P indicates the significance, according to Student's t test, of the difference between mutant and control for each tRNA.

Analysis of Aminoacylation of tRNAs

We tested whether the deficient thiouridylation of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln caused by the TRMU A10S mutation affects the aminoacylation of above tRNA as well as other tRNA. Indeed, our previous investigation also showed that the TRMU A10S mutation caused the reductions in the steady state levels of other tRNAs (25). The aminoacylation capacities of tRNALys, tRNATyr, tRNALeu(CUN), and tRNASer(AGY) in control and mutant cell lines were examined by the use of electrophoresis in an acid polyacrylamide/urea gel system to separate uncharged tRNA species from the corresponding charged tRNA, electroblotting, and hybridizing with above tRNA probes (15, 48, 49). As shown in Fig. 5, the upper band represented the charged tRNA, and the lower band was uncharged tRNA. Electrophoretic patterns showed that either charged or uncharged tRNASer(AGY) in all mutant cell lines migrated slower than control cell lines. The conformation change may be due to the presence of the m.12236G→A mutation in the tRNASer(AGY) gene in the mutant cell lines (18) (supplemental Table S1). However, there were no obvious differences in electrophoretic mobility of tRNALys, tRNATyr, and tRNALeu(CUN) between mutant and control cell lines. Notably, the efficiencies of aminoacylated tRNALys in cell lines carrying only m.1555A→G mutation, both m.1555A→G and heterozygous or homozygous TRMU A10S mutations were 103, 137, and 137% of those in control cell lines. Moreover, the efficiencies of aminoacylated tRNALeu(CUN) in cells harboring only m.1555A→G mutation, both m.1555A→G and heterozygous or homozygous TRMU A10S mutations were 117, 138, and 135% of those in control cell lines, whereas the efficiencies of aminoacylated tRNASer(AGY) in those cell lines were 115, 126, and 129% of those in control cell lines. However, the levels of aminoacylation in tRNATyr in mutant cell lines were comparable with those in the control cell lines.

FIGURE 5.

In vivo aminoacylation assays. A, 2 μg of total mitochondrial RNAs purified from eight cell lines under acid conditions were electrophoresed at 4 °C through an acid (pH 5.2) 10% polyacrylamide with 7 m urea gel, electroblotted, and hybridized with a DIG-labeled oligonucleotide probe-specific for the tRNALys, tRNATyr, tRNALeu(CUN), and tRNASer(AGY), respectively. B, in vivo aminoacylated proportions of tRNALys, tRNATyr, tRNALeu(CUN), and tRNASer(AGY) in the mutant and controls. The calculations were based on three independent determinations. Graph details and symbols are explained in the legend to Fig. 4.

Reductions in the Level of Mitochondrial Proteins

To further determine whether the TRMU A10S mutation alters mitochondrial translation, the Western blotting analysis was carried out to examine the levels of seven mtDNA encoding polypeptides in mutant and control cells with VDAC as a loading control. As shown in Fig. 6A, the levels of CO2 (subunit II of cytochrome c oxidase); ND1, ND4, ND5, and ND6 (subunits 1, 4, 5, and 6 of NADH dehydrogenase); A6 (subunit 6 of the H+-ATPase); and CYTB (apocytochrome b) were decreased in mutant cell lines, as compared with those control cell lines. As shown in Fig. 6B, the overall levels of seven mitochondrial translation products in mutant cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations were 42%, relative to the mean value measured in the control cell lines. Notably, the average levels of ND1, ND4, ND5, ND6, CO2, A6, and CYTB in these mutant cells carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations were 36, 40, 53, 24, 54, 51, and 37% of the average values of control cells, respectively. Furthermore, the overall levels of seven mitochondrial proteins in cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations were 55%, relative to those in controls. Moreover, the overall levels of seven mitochondrial translation products in mutant cell line carrying only m.1555A→G mutation were 73% of control cell lines. However, the levels of synthesis of polypeptides in mutants relative to that in controls did not correlate with either the number of codons or proportion of glutamic acid, glutamine, and lysine residues (supplemental Table S2).

FIGURE 6.

Western blotting analysis of mitochondrial proteins. A, 20 μg of total cellular proteins from lymphoblastoid cell lines were electrophoresed through a SDS-polyacrylamide gel, electroblotted, and hybridized with seven respiratory complex subunits in mutant and control cells with VADC as a loading control. CO2, subunit II of cytochrome c oxidase; ND1, ND4, ND5, and ND6, subunits 1, 4, 5, and 6 of the reduced nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide dehydrogenase; A6, subunit 6 of the H+-ATPase; and CYTB, apocytochrome b. B, quantification of mitochondrial protein levels. Average content of CO2, ND1, ND4, ND5, ND6, A6 and CYTB per cell, normalized to the average content of VADC per cell in mutant cell lines and controls. The values for the mutant cell lines are expressed as percentages of the average values for the control cell lines. The horizontal dashed lines represent the average value for each group. The calculations were based on three independent determinations. Graph details and symbols are explained in the legend to Fig. 4.

Respiration Defects

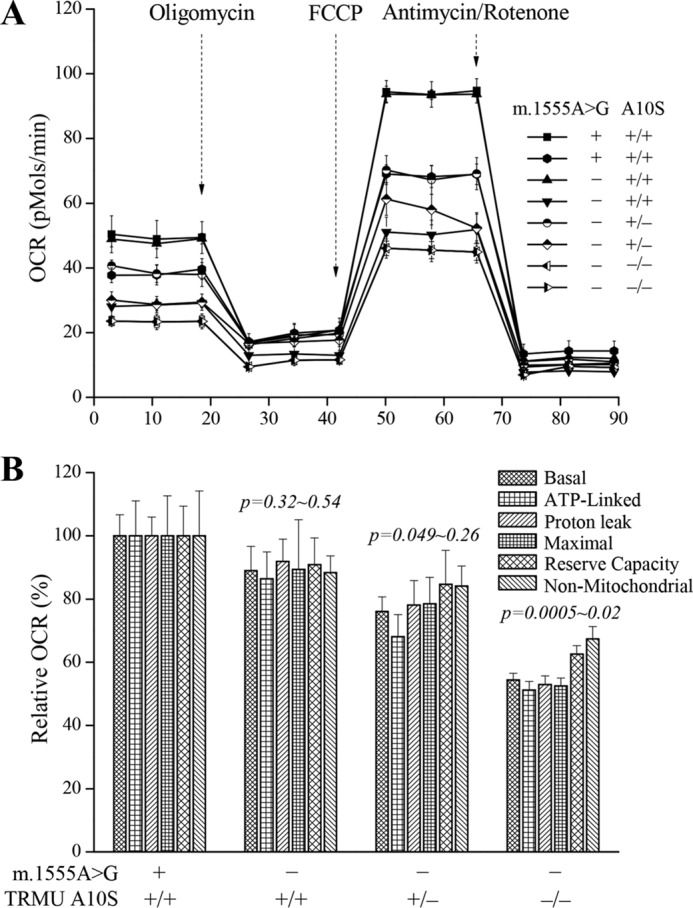

To evaluate whether the TRMU A10S mutation affects cellular bioenergetics, we examined the oxygen consumption rates (OCRs) of mutant and control cell lines (50). As shown in Fig. 7, the average basal OCRs in mutant cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous or heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations, and only m.1555A→G mutation were 54, 76, and 88%, relative to the mean value measured in the control cell lines, respectively. To investigate which of the enzyme complexes of the respiratory chain was affected in the mutant cell lines, OCR were measured after the sequential addition of oligomycin (inhibit the ATP synthase), FCCP (to uncouple the mitochondrial inner membrane and allow for maximum electron flux through the ETC), rotenone (to inhibit complex I), and antimycin A (to inhibit complex III). The difference between the basal OCR and the drug-insensitive OCR yields the amount of ATP-linked OCR, proton leak OCR, maximal OCR, reserve capacity, and non-mitochondrial OCR. As shown in Fig. 6, the ATP-linked OCR, proton leak OCR, maximal OCR, reserve capacity, and non-mitochondrial OCR were 51, 53, 53, 63, and 67% in the mutant cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations and 68, 78, 78, 85, and 84% in the mutant cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations relative to the control cell lines, respectively. Moreover, the above five kinds of OCR levels in mutant cell line carrying only m.1555A→G mutation were 86, 92, 89, 91, and 88% of control cell lines.

FIGURE 7.

Respiration assays. A, an analysis of O2 consumption in the various cell lines using different inhibitors. The OCRs were first measured on 5 × 104 cells of each cell line under basal condition and then sequentially added to oligomycin (1.5 μm), carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (0.8 μm), rotenone (1 μm), and antimycin A (5 μm) at indicated times to determine different parameters of mitochondrial functions. B, graphs presented the ATP-linked OCR, proton leak OCR, maximal OCR, reserve capacity, and non-mitochondrial OCR in mutant and control cell lines. Non-mitochondrial OCR was determined as the OCR after rotenone/antimycin A treatment. Basal OCR was determined as OCR before oligomycin minus OCR after rotenone/antimycin. ATP-linked OCR was determined as OCR before oligomycin minus OCR after oligomycin. Proton leak was determined as basal OCR minus ATP-linked OCR. Maximal OCR was determined as the OCR after FCCP minus non-mitochondrial OCR. Reserve capacity was defined as the difference between maximal OCR after FCCP minus basal OCR. The average of four determinations for each cell line is shown. The horizontal dashed lines represent the average value for each group. Graph details and symbols are explained in the legend to Fig. 4.

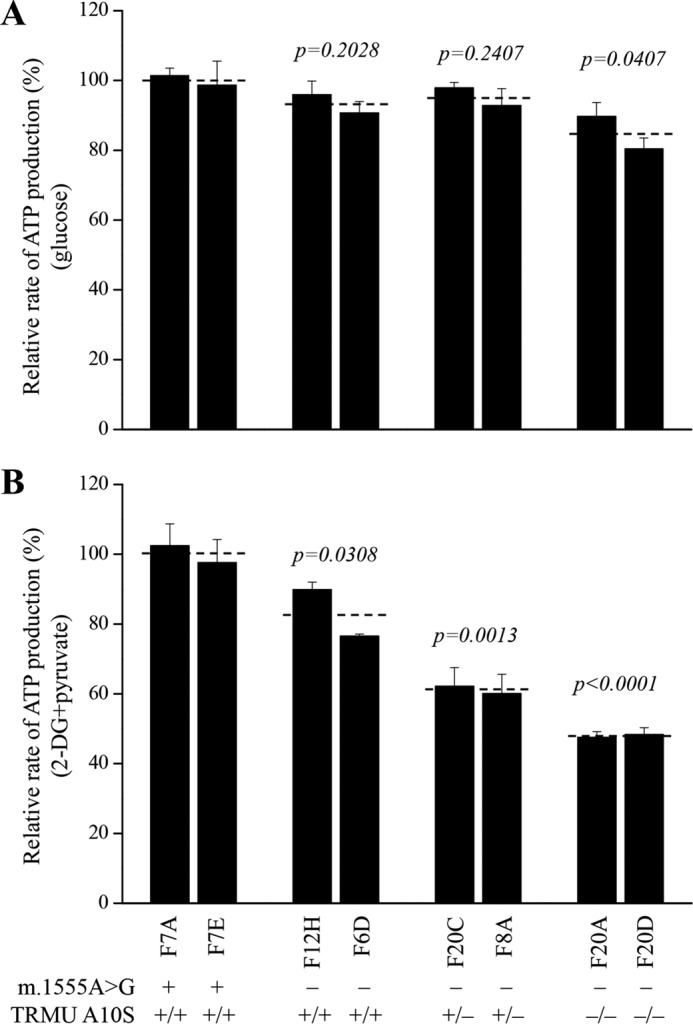

Reduced Levels in Mitochondrial ATP Production

The capacity of oxidative phosphorylation in mutant and wild-type cells was examined by measuring the levels of cellular and mitochondrial ATP using a luciferin/luciferase assay. Populations of cells were incubated in the media in the presence of glucose, and 2-deoxy-d-glucose with pyruvate (15). As shown in Fig. 8A, in the presence of glucose (total cellular levels of ATP), the average levels of ATP production in mutant cells carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous or heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations and only m.1555A→G mutation were 93, 95, and 85%, relative to the mean value measured in the control cell lines, respectively. In the presence of pyruvate and 2-deoxy-d-glucose to inhibit the glycolysis (mitochondrial levels of ATP), as shown in Fig. 8B, the levels of ATP production in mutant cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous or heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations and only m.1555A→G mutation were 48, 61, and 83% of the mean value measured in the control cell lines, respectively.

FIGURE 8.

Measurement of cellular and mitochondrial ATP levels using bioluminescence assay. The cells were incubated with 10 mm glucose or 5 mm 2-deoxy-d-glucose plus 5 mm pyruvate to determine ATP generation under mitochondrial ATP synthesis. The average rates of ATP level per cell line are shown. A, ATP level in total cells. B, ATP level in mitochondria. Six to seven determinations were made for each cell line. Graph details and symbols are explained in the legend to Fig. 4.

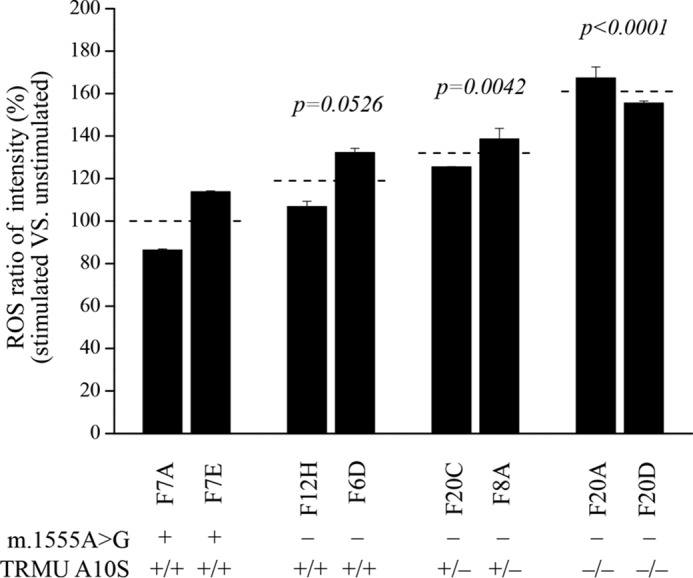

The Increase of ROS Production

It was anticipated that respiration defects increase the production of ROS. The levels of the ROS generation in the vital cells derived from six mutant cell carrying the m.1555A→G mutation with or without TRMU A10S mutation and two control cell lines lacking both mutations were measured with flow cytometry under normal and H2O2 stimulation (51, 52). Geometric mean intensity was recorded to measure the rate of ROS of each sample. The ratio of geometric mean intensity between unstimulated and stimulated with H2O2 in each cell line was calculated to delineate the reaction upon increasing level of ROS under oxidative stress. As shown in Fig. 9, the levels of ROS generation in the mutant cell lines cells carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations ranged from 155 to 167%, with an average 161% of the mean value measured in the control cell lines. Moreover, ROS generation levels of cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations and mutant cells carrying only m.1555A→G mutation were 132 and 120% of controls, respectively.

FIGURE 9.

Ratio of geometric mean intensity between levels of the ROS generation in the vital cells with or without H2O2 stimulation. The rates of production in ROS from mutant cell lines and control cell lines were analyzed by BD-LSR II flow cytometer system with or without H2O2 stimulation. The relative ratio of intensity (stimulated versus unstimulated with H2O2) was calculated. The average of four determinations for each cell line is shown. Graph details and symbols are explained in the legend to Fig. 4.

Discussion

The nuclear modifier genes were proposed to modulate the phenotypic manifestation of deafness-associated 12S rRNA mutations (3, 4, 53). In the present study, we further characterized the nuclear modifier allele (A10S) in the TRMU, which interacts with m.1555A→G mutation to cause deafness. Human TRMU encodes a highly conserved 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridylate-methyltransferase responsible for the biosynthesis of 5-taurinomethyl-2-thiouridine (τm5s2U) nucleotides at the wobble position of mitochondrial tRNAGln, tRNAGlu, and tRNALys (30, 31). The highly conserved Ala10 residue locates at the N-terminal region of this polypeptide. In all available TRMU/MnmA protein sequences, residue 10 is highly conserved, either Ala or Gly. Based on our MD simulation results, either Ala10 or Gly10 does not interact with helix 4 of the protein (43). The change of alanine 10 residue with serine introduces the Ser10 dynamic electrostatic interaction with the Lys106 residue of helix 4 within the catalytic domain of TRMU. Thus, it was hypothesized that the A10S mutation altered the stability and catalytic activity of TRMU. A Western blotting analysis showed markedly reduced levels of TRMU in cell lines carrying the A10S mutation. Furthermore, the thermal shift assay revealed that the Tm value of mutant TRMU protein was lower than those of wild-type TRMU. These data are strong evidences that A10S mutation caused the instability of TRMU.

The primary defect in the A10S mutation was the deficient 2-thiouridine modification of U34 of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln. In the present study, 48, 38, and 50% decreases in 2-thiouridine modification of U34 of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln were observed in mutant cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous A10S mutations, as compared with controls. These results were consistent with the fact that the small interfering RNA down-regulation of or other mutations of TRMU led to the defects in 2-thiouridylation in mitochondrial tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln (34, 54, 55). Furthermore, in vitro assays showed that the deficient synthesis of s2U34 altered the tRNA aminoacylation, because s2U34 serves as a determinant for tRNA recognition by cognate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in bacteria (39, 56). However, in vivo assays revealed that the lack of 5-methyl-aminomethyl group did not affect the charging levels for tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln in bacteria (56). In the present study, the efficiencies of aminoacylated tRNALys, tRNALeu(CUN), and tRNASer(AGY) in cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations were 137, 135, and 129% of those in control cell lines. These data suggested that the TRMU A10S mutation may increase the charging levels for tRNALys, tRNALeu(CUN), and tRNASer(AGY). An increase in aminoacylation of tRNAs in mutant cell lines may be due to the instability of the mutant tRNA, where aminoacylation may provide some levels of stabilization by compensatory effect (15, 57, 58). Alternatively, these tRNAs may be mischarged with a noncognate amino acids, because anticodon modifications act as antideterminants (59). Therefore, an inefficient modification of tRNAs caused by the TRMU mutations may then make these tRNAs to be metabolically less stable and more subject to degradation, thereby lowering the level of the tRNAs (25, 35, 54, 55).

A failure in the tRNA metabolism caused by the TRMU A10S mutation should be responsible for the impairment of mitochondrial translation. In particular, the mischarged tRNAs may cause the global protein misfolding (32, 59). In fact, the mtDNA encoded 13 polypeptides in the complexes of the oxidative phosphorylation system (ND1–6; ND4L of complex I; CYTB of complex III; CO1, CO2, and CO3 of complex IV; and ATP6 and ATP8 of complex V) (6, 60). In the present study, 58, 45, and 27% reductions in the levels of mitochondrial proteins were observed in mutant cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous or heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations and only m.1555A→G mutation, respectively. These results were comparable with the in vivo pulse-labeling mitochondrial protein synthesis assay (21, 25). Notably, variable decreases in the levels of seven mtDNA-encoded polypeptides were observed in mutant cell lines. In particular, cell lines carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations exhibited marked reductions (from 46 to 76%) in the levels of seven polypeptides. However, the levels of synthesis of polypeptides in mutants relative to that in controls did not correlate with either the number of codons or proportion of glutamic acid, glutamine, and lysine residues. These data were not fully comparable with the case of MERRF-associated m.8344A→G mutation in tRNALys gene (61). The impairment of mitochondrial protein synthesis was apparently responsible for the reduced rates in the basal OCR or ATP-linked OCR reserve capacity and maximal OCR among the control and mutant cell lines. In particular, the 12, 34, and 46% decreases in basal OCR were observed in cell lines harboring only m.1555A→G mutation, both m.1555A→G and heterozygous or homozygous TRMU A10S mutations, respectively. This correlation is clearly consistent with the importance that a failure in tRNA metabolism plays a critical role in producing their respiration defects in deafness patients carrying the m.1555A→G mutation.

The respiratory deficiency then affects the efficiency of mitochondrial ATP synthesis. In this investigation, the m.1555A→G mutation caused 17% reduction of mitochondrial ATP production in lymphoblastoid cell lines, as in the cases of cell lines bearing the LHON-associated m.11778G→A mutations (62, 63). By contrast, the ∼52% drop in mitochondrial ATP production in lymphoblastoid cell lines bearing both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations may result from the defective activities of respirations caused by both m.1555A→G mutation and altered tRNA metabolism associated with TRMU A10S mutation. These data are consistent with the fact that 20 and 51% reductions in mitochondrial ATP production were observed in lymphoblastoid cell lines carrying the only m.11778G→A and both m.11778G→A and homozygous YARS2 p.191Gly→Val mutations (62). Alternatively, the reduction in mitochondrial ATP production in mutant cells was likely a consequence of the decrease in the proton electrochemical potential gradient of mutant mitochondria (64). As a result, the hair cells carrying the mtDNA mutation may be particularly sensitive to increased ATP demand (3, 4, 65). The impairment of oxidative phosphorylation can lead to more electron leakage from electron transport chain and, in turn, elevate the production of ROS in mutant cells (66), thereby damaging mitochondrial and cellular proteins, lipids, and nuclear acids (67). However, a 61% increase of ROS production in cells carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations was the consequence of the altered activities of respiration. The hair cells and cochlear neurons may be preferentially involved because they are somehow exquisitely sensitive to subtle imbalance in cellular redox state or increased level of free radicals (68–70). This would lead to dysfunction or apoptosis of hair cells and cochlear neurons carrying both m.1555A→G and TRMU A10S mutations, thereby producing a phenotype of deafness.

In summary, our study demonstrated the role of the first nuclear modifier allele (A10S) in the TRMU gene in the phenotypic manifestation of deafness-associated m.1555A→G mutation. The A10S mutation altered the structure and function of TRMU. The mutated TRMU caused the deficient thiolation of tRNAGln, tRNAGlu, and tRNALys but increased the aminoacylation of tRNAs. The failures in tRNA metabolism led to impairment of mitochondrial translation, respiratory phenotype, defects in mitochondrial ATP production, and increasing ROS production. The resultant biochemical defects aggravate the mitochondrial dysfunction associated with m.1555A→G mutation, below the threshold for normal cell function, thereby expressing the deafness phenotype. Therefore, the mutated TRMU, acting as a nuclear modifier, triggers the deafness in individuals harboring the m.1555A→G mutation.

Experimental Procedures

MD Simulations

Simulation systems. The starting coordinates of wild-type TRMU were taken from the crystal structure of TRMU-tRNAGlu complex (Protein Data Bank entry 2DER) (44). The coordinates of A10S mutation mutated protein were generated from the wild-type TRMU coordinates through PyMOL (Schrödinger). All terminal residues adopted the neutral state. Each system was solvated in a cubic box of TIP3P water with an extension of at least 10 Å from each side. Approximately 50 mm NaCl were added to the solvent in addition to the neutralizing Na+ or Cl−. This leads to a wild-type system of 109422 atoms and a mutant system of 109426 atoms.

Simulation protocol. MD simulations were carried out with the GROMACS 4.5.5 package 2 (42). The CHARMM363 force field with CMAP modification 4 was applied for protein (43). Energy minimizations were performed to relieve unfavorable contacts, followed with equilibration steps to fully equilibrate the solvent. Each system was equilibrated in the NPT ensemble at 310 K and 1 bar in periodic boundary condition, and the time step was set to 1 fs. Positional restraints were first applied on all the heavy atoms of protein for 50 ps, then main chain atoms for 50 ps, and then α-atoms for 500 ps. After equilibrations, the production simulation was carried out with a time step of 2 fs, and each system was run up to 300 ns. Electrostatic interactions were calculated with the particle mesh Ewald algorithm (71). SETTLE constraint was applied on hydrogen-involved covalent bonds in water, and LINCS constraint was applied on the hydrogen-involved covalent bonds in those molecules other than waters in the system (72).

Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Eight human immortalized lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from members of an Arab-Israeli family (two subjects carrying only m.1555A→G mutation (F12H and F6D), two individuals (F20C and F8A) harboring both m.1555A→G and heterozygous TRMU A10S mutations, two individuals (F20A and F20D) carrying both m.1555A→G and homozygous TRMU A10S mutations, and two control individuals (F7A and F7E) lacking both mutations) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1 mm sodium pyruvate and 10% FBS (15, 21).

Differential Scanning Fluorimetry

The wild-type and mutant human TRMU cDNAs were amplified by PCR and cloned in-frame with a C-terminal His tag into pET-28a vector (25). Recombinant wild-type and mutant TRMU were produced as His tag fusion proteins in Escherichia coli Rosetta (DE3) as detailed elsewhere (73). The proteins were purified using a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid column (Qiagen). The stability of proteins was assessed using a protein thermal shift dye kit (Life Technologies) unfolding temperature (Tm) test performed on a 7900 HT Fast real time polymerase chain reaction detection system, according to the modified manufacturer's instructions. The data were analyzed as detailed elsewhere (44). The Tm value was estimated from the transition midpoint of the fluorescence curve, which corresponds to temperature at which half of the protein population is unfolded.

Mitochondrial tRNA Thiolation Analysis

Total mitochondrial RNAs were obtained using a Totally RNATM kit (Ambion) from mitochondria isolated from mutant and wild-type cell lines, as described previously (74). The presence of the thiouridine modification in the tRNAs was verified by the retardation of electrophoretic mobility in a polyacrylamide gel that contains 0.05 mg/ml APM (45–47). 2 μg of total mitochondrial RNA was separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and blotted onto positively charged membrane (Roche Applied Science). Each tRNA fraction was detected with a specific non-radioactive DIG oligodeoxynucleoside probe at the 3′ termini according to the method as described elsewhere (15, 25, 47). Oligonucleotide probes for tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln were detailed previously (15, 25). DIG-labeled oligodeoxynucleosides were generated by using the DIG oligonucleoside tailing kit (Roche). APM gel electrophoresis and quantification of 2-thiouridine modification in tRNAs were conducted as detailed (25).

Mitochondrial tRNA Aminoacylation Analysis

Total mitochondrial RNAs were isolated under acidic condition. 2 μg of total mitochondrial RNA was electrophoresed at 4 °C through an acid (pH 5.2) 10% polyacrylamide with 7 m urea gel to separate the charged and uncharged tRNA as detailed elsewhere (48). The gels were then electroblotted onto a positively charged nylon membrane (Roche) for the hybridization analysis with oligodeoxynucleotide probes of tRNALys, tRNATyr, tRNALeu(CUN), and tRNASer(AGY), as described elsewhere (25, 48–49). DIG-labeled oligodeoxynucleotides were generated by using a DIG oligonucleotide tailing kit (Roche). The hybridization and quantification of density in each band were carried out as detailed elsewhere (48, 49).

Western Blotting Analysis

Western blotting analysis was performed as detailed previously (15, 49). The antibodies used for this investigation were from Abcam (TRMU (ab50895), VDAC (ab14734), NDUFB8 (ab110411), ND1 (ab74257), ND5 (ab92624) and A6 (ab101908), and CO2 (ab110258)), Santa Cruz Biotechnology (ND4 (sc-20499-R), ND6 (sc-20667)), MTO1 (sc-398760), and Proteintech (CYTB (55090-1-AP)). Peroxidase Affini Pure goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson) were used as secondary antibodies, and protein signals were detected using the ECL system (CWBIO). Quantification of density in each band was performed as detailed previously (15, 49).

Measurements of Oxygen Consumption

The rates of oxygen consumption in cybrid cell lines were measured with a Seahorse Bioscience XF-96 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience), as detailed previously (15, 50).

ATP Measurements

The Cell Titer-Glo® luminescent cell viability assay kit (Promega) was used for the measurement of cellular and mitochondrial ATP levels, according to the modified manufacturer's instructions (15, 49, 62).

Measurement of ROS Production

ROS measurements were performed following the procedures detailed previously (51–52).

Computer Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test contained in the Microsoft Excel program for Macintosh (version 2007). Differences were considered significant at a p < 0.05.

Author Contributions

F. M. performed the experiments and contributed to data analysis in Figs. 2, 3, and 6–9. X. C. and Z. Z. carried out the MD simulations. Y. P. performed the aminoacylation experiment. R. L. did the thiolation analysis. F. L. and Q. F. contributed to the Western blotting analysis. A. S. G. performed the statistical analysis. N. F.-G. provided the cell lines. M.-X. G. designed the experiments, and M.-X. G. and X. Z. monitored the project progression, data analysis, and interpretation. F. M. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. M.-X. G. made the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 81330024, National Basic Research Priorities Program of China Grant 2014CB541704, NIDCD National Institutes of Health Grants RO1DC05230 and RO1DC07696 (to M.-X. G.), National Natural Science Foundation of China Grant 31400709 (to X. C.), and National Basic Research Priorities Program of China Grant 2012CB967902 (to X. Z.). The MD simulations were carried out at National Supercomputer Center in Tianjin, China. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

- mtDNA

- mitochondrial DNA

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- RMSF

- root mean square fluctuation

- DSF

- differential scanning fluorimetry

- APM

- ((N-acryloylamino)phenyl) mercuric chloride

- DIG

- digoxingenin

- OCR

- oxygen consumption rate.

References

- 1. Jacobs H. (2003) Disorders of mitochondrial protein synthesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, R293–R301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rötig A. (2011) Human diseases with impaired mitochondrial protein synthesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1807, 1198–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fischel-Ghodsian N. (1999) Mitochondrial deafness mutations reviewed. Hum. Mutat. 13, 261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guan M. X. (2011) Mitochondrial 12S rRNA mutations associated with aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Mitochondrion 11, 237–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zheng J., Ji Y., and Guan M. X. (2012) Mitochondrial tRNA mutations associated with deafness. Mitochondrion 12, 406–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andrews R. M., Kubacka I., Chinnery P. F., Lightowlers R. N., Turnbull D. M., and Howell N. (1999) Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 23, 147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Calvo S. E., and Mootha V. K. (2010) The mitochondrial proteome and human disease. Annu. Rev. Genomics. Hum. Genet. 11, 25–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pierce S. B., Gersak K., Michaelson-Cohen R., Walsh T., Lee M. K., Malach D., Klevit R. E., King M. C., and Levy-Lahad E. (2013) Mutations in LARS2, encoding mitochondrial leucyl-tRNA synthetase, lead to premature ovarian failure and hearing loss in Perrault syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 614–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simon M., Richard E. M., Wang X., Shahzad M., Huang V. H., Qaiser T. A., Potluri P., Mahl S. E., Davila A., Nazli S., Hancock S., Yu M., Gargus J., Chang R., Al-Sheqaih N., et al. (2015) Mutations of human NARS2, encoding the mitochondrial asparaginyl-tRNA synthetase, cause nonsyndromic deafness and Leigh syndrome. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Santos-Cortez R. L., Lee K., Azeem Z., Antonellis P. J., Pollock L. M., Khan S., Irfanullah, Andrade-Elizondo P. B., Chiu I., Adams M. D., Basit S., Smith J. D., University of Washington Center for Mendelian Genomics, Nickerson D. A., McDermott B. M. Jr., et al. (2013) Mutations in KARS, encoding Lysyl-tRNA synthetase, cause autosomal-recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment DFNB89. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 93, 132–140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Iwanicka-Pronicka K., Pollak A., Skórka A., Lechowicz U., Pajdowska M., Furmanek M., Rzeski M., Korniszewski L., Skarzynski H., and Ploski R. (2012) Postlingual hearing loss as a mitochondrial 3243A→G mutation phenotype. PLoS One 7, e44054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guan M. X., Enriquez J. A., Fischel-Ghodsian N., Puranam R. S., Lin C. P., Maw M. A., and Attardi G. (1998) The deafness-associated mitochondrial DNA mutation at position 7445, which affects tRNASer(UCN) precursor processing, has long-range effects on NADH dehydrogenase subunit ND6 gene expression. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 5868–5879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li X., Fischel-Ghodsian N., Schwartz F., Yan Q., Friedman R. A., and Guan M. X. (2004) Biochemical characterization of the mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) T7511C mutation associated with nonsyndromic deafness. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 867–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tang X., Zheng J., Ying Z., Cai Z., Gao Y., He Z., Yu H., Yao J., Yang Y., Wang H., Chen Y., and Guan M. X. (2015) Mitochondrial tRNASer(UCN) variants in 2651 Han Chinese subjects with hearing loss. Mitochondrion 23, 17–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gong S., Peng Y., Jiang P., Wang M., Fan M., Wang X., Zhou H., Li H., Yan Q., Huang T., and Guan M. X. (2014) A deafness-associated tRNAHis mutation alters the mitochondrial function, ROS production and membrane potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 8039–8048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang M., Liu H., Zheng J., Chen B., Zhou M., Fan W., Wang H., Liang X., Zhou X., Eriani G., Jiang P., and Guan M. X. (2016) A deafness and diabetes associated tRNA mutation caused the deficient pseudouridinylation at position 55 in tRNAGlu and mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 21029–21041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang M., Peng Y., Zheng J., Zheng B., Jin X., Liu H., Wang Y., Tang X., Huang T., Jiang P., and Guan M. X. (2016) A deafness-associated tRNAAsp mutation alters the m1G37 modification, aminoacylation and stability of tRNAAsp and mitochondrial function. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 10974–10985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prezant T. R., Agapian J. V., Bohlman M. C., Bu X., Oztas S., Qiu W. Q., Arnos K. S., Cortopassi G. A., Jaber L., and Rotter J. I (1993) Mitochondrail ribosomal-RNA mutation associated with both antibiobic-reduced and non-syndromic deafness. Nat. Genet. 4, 289–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao H., Li R., Wang Q., Yan Q., Deng J. H., Han D., Bai Y., Young W. Y., and Guan M. X. (2004) Maternally inherited aminoglycoside-induced and nonsyndromic deafness is associated with the novel C1494T mutation in the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene in a large chinese family. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74, 139–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lu J., Li Z., Zhu Y., Yang A., Li R., Zheng J., Cai Q., Peng G., Zheng W., Tang X., Chen B., Chen J., Liao Z., Yang L., Li Y., et al. (2010) Mitochondrial 12S rRNA variants in 1642 Han Chinese pediatric subjects with aminoglycoside-induced and nonsyndromic hearing loss. Mitochondrion 10, 380–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guan M. X., Fischel-Ghodsian N., and Attardi G. (1996) Biochemical evidence for nuclear gene involvement in phenotype of non-syndromic deafness associated with mitochondrial 12S rRNA mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5, 963–971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guan M. X., Fischel-Ghodsian N., and Attardi G. (2001) Nuclear background determines biochemical phenotype in the deafness-associated mitochondrial 12S rRNA mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 573–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhao H., Young W. Y., Yan Q., Li R., Cao J., Wang Q., Li X., Peters J. L., Han D., and Guan M. X. (2005) Functional characterization of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA C1494T mutation associated with aminoglycoside-induced and nonsyndromic hearing loss. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 1132–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guan M. X., Fischel-Ghodsian N., and Attardi G. (2000) A biochemical basis for the inherited susceptibility to aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 1787–1793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guan M. X., Yan Q., Li X., Bykhovskaya Y., Gallo-Teran J., Hajek P., Umeda N., Zhao H., Garrido G., Mengesha E., Suzuki T., del Castillo I., Peters J. L., Li R., Qian Y., et al. (2006) Mutation in TRMU related to transfer RNA modification modulates the phenotypic expression of the deafness-associated mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79, 291–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bykhovskaya Y., Mengesha E., Wang D., Yang H., Estivill X., Shohat M., and Fischel-Ghodsian N. (2004) Phenotype of non-syndromic deafness associated with the mitochondrial A1555G mutation is modulated by mitochondrial RNA modifying enzymes MTO1 and GTPBP3. Mol. Genet. Metab. 83, 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li X., Li R., Lin X., and Guan M. X. (2002) Isolation and characterization of the putative nuclear modifier gene MTO1 involved in the pathogenesis of deafness-associated mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27256–27264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li X., and Guan M. X. (2002) A human mitochondrial GTP binding protein related to tRNA modification may modulate the phenotypic expression of the deafness-associated mitochondrial 12S rRNA mutation. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 7701–7711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yan Q., Bykhovskaya Y., Li R., Mengesha E., Shohat M., Estivill X., Fischel-Ghodsian N., and Guan M. X. (2006) Human TRMU encoding the mitochondrial 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridylate-methyltransferase is a putative nuclear modifier gene for the phenotypic expression of the deafness-associated 12S rRNA mutations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 342, 1130–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yan Q., Li X., Faye G., and Guan M. X. (2005) Mutations in MTO2 related to tRNA modification impair mitochondrial gene expression and protein synthesis in the presence of a paromomycin resistance mutation in mitochondrial 15S rRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29151–29157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suzuki T., and Suzuki T. (2014) A complete landscape of post-transcriptional modifications in mammalian mitochondrial tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 7346–7357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Allnér O., and Nilsson L. (2011) Nucleotide modifications and tRNA anticodon-mRNA codon interactions on the ribosome. RNA. 17, 2177–2188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Motorin Y., and Helm M. (2010) tRNA stabilization by modified nucleotides. Biochemistry 49, 4934–4944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Umeda N., Suzuki T., Yukawa M., Ohya Y., Shindo H., Watanabe K., and Suzuki T. (2005) Mitochondria-specific RNA-modifying enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of the wobble base in mitochondrial tRNAs. Implications for the molecular pathogenesis of human mitochondrial diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 1613–1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sasarman F., Antonicka H., Horvath R., and Shoubridge E. A. (2011) The 2-thiouridylase function of the human MTU1 (TRMU) enzyme is dispensable for mitochondrial translation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 4634–4643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kambampati R., and Lauhon C. T. (2003) MnmA and IscS are required for in vitro 2-thiouridine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 42, 1109–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yan Q., and Guan M. X. (2004) Identification and characterization of mouse TRMU gene encoding the mitochondrial 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridylate-methyltransferase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1676, 119–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Armengod M. E., Meseguer S., Villarroya M., Prado S., Moukadiri I., Ruiz-Partida R., Garzón M. J., Navarro-González C., and Martínez-Zamora A. (2014) Modification of the wobble uridine in bacterial and mitochondrial tRNAs reading NNA/NNG triplets of 2-codon boxes. RNA Biol. 11, 1495–1507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sylvers L. A., Rogers K. C., Shimizu M., Ohtsuka E., and Söll D. (1993) A 2-thiouridine derivative in tRNAGlu is a positive determinant for aminoacylation by Escherichia coli glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochemistry 32, 3836–3841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bykhovskaya Y., Shohat M., Ehrenman K., Johnson D., Hamon M., Cantor R. M., Aouizerat B., Bu X., Rotter J. I., Jaber L., and Fischel-Ghodsian N. (1998) Evidence for complex nuclear inheritance in a pedigree with nonsyndromic deafness due to a homoplasmic mitochondrial mutation. Am. J. Med. Genet. 77, 421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hess B., Kutzner C., van der Spoel D., and Lindahl E. (2008) GROMACS 4: Algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory. Comput. 4, 435–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Huang J., and MacKerell A. D. Jr. (2013) CHARMM36 all-atom additive protein force field: validation based on comparison to NMR data. J. Comput. Chem. 34, 2135–2145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Numata T., Ikeuchi Y., Fukai S., Suzuki T., and Nureki O. (2006) Snapshots of tRNA sulphuration via an adenylated intermediate. Nature 442, 419–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Niesen F. H., Berglund H., and Vedadi M. (2007) The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat. Protoc. 2, 2212–2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shigi N., Suzuki T., Tamakoshi M., Oshima T., and Watanabe K. (2002) Conserved bases in the T Psi C loop of tRNA are determinants for thermophile-specific 2-thiouridylation at position 54. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39128–39135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Suzuki T., Suzuki T., Wada T., Saigo K., and Watanabe K. (2002) Taurine as a constituent of mitochondrial tRNAs: new insights into the functions of taurine and human mitochondrial diseases. EMBO J. 21, 6581–6589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wang X., Yan Q., and Guan M. X. (2010) Combination of the loss of cmnm5U34 with the lack of s2U34 modifications of tRNALys, tRNAGlu, and tRNAGln altered mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration. J. Mol. Biol. 395, 1038–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Enríquez J. A., and Attardi G. (1996) Analysis of aminoacylation of human mitochondrial tRNAs. Methods Enzymol. 264, 183–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jiang P., Wang M., Xue L., Xiao Y., Yu J., Wang H., Yao J., Liu H., Peng Y., Liu H., Li H., Chen Y., and Guan M. X. (2016) A hypertension-associated tRNAAla mutation alters the tRNA metabolism and mitochondrial function. Mol. Cell Biol. 36, 1920–1930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dranka B. P., Benavides G. A., Diers A. R., Giordano S., Zelickson B. R., Reily C., Zou L., Chatham J. C., Hill B. G., Zhang J., Landar A., and Darley-Usmar V. M. (2011) Assessing bioenergetic function in response to oxidative stress by metabolic profiling. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 51, 1621–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mahfouz R., Sharma R., Lackner J., Aziz N., and Agarwal A. (2009) Evaluation of chemiluminescence and flow cytometry as tools in assessing production of hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion in human spermatozoa. Fertil Steril. 92, 819–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yu J., Zheng J., Zhao X., Liu J., Mao Z., Ling Y., Chen D., Chen C., Hui L., Cui L., Chen Y., Jiang P., and Guan M. X. (2014) Aminoglycoside stress together with the 12S rRNA 1494C→T mutation leads to mitophagy. PLoS One 9, e114650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen C., Chen Y., and Guan M. X. (2015) A peep into mitochondrial disorder: multifaceted from mitochondrial DNA mutations to nuclear gene modulation. Protein Cell 6, 862–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boczonadi V., Smith P. M., Pyle A., Gomez-Duran A., Schara U., Tulinius M., Chinnery P. F., and Horvath R. (2013) Altered 2-thiouridylation impairs mitochondrial translation in reversible infantile respiratory chain deficiency. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 4602–4615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zeharia A., Shaag A., Pappo O., Mager-Heckel A. M., Saada A., Beinat M., Karicheva O., Mandel H., Ofek N., Segel R., Marom D., Rötig A., Tarassov I., and Elpeleg O. (2009) Acute infantile liver failure due to mutations in the TRMU gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 85, 401–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Krüger M. K., and Sørensen M. A. (1998) Aminoacylation of hypomodified tRNAGlu in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 284, 609–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Belostotsky R., Frishberg Y., and Entelis N. (2012) Human mitochondrial tRNA quality control in health and disease: a channelling mechanism? RNA Biol. 9, 33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kern A. D., and Kondrashov F. A. (2004) Mechanisms and convergence of compensatory evolution in mammalian mitochondrial tRNAs. Nat. Genet. 36, 1207–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Giegé R., Sissler M., and Florentz C. (1998) Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 26, 5017–5035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wallace D. C. (2005) A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39, 359–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Enriquez J. A., Chomyn A., and Attardi G. (1995) MtDNA mutation in MERRF syndrome causes defective aminoacylation of tRNALys and premature translation termination. Nat. Genet. 10, 47–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jiang P., Jin X., Peng Y., Wang M., Liu H., Liu X., Zhang Z., Ji Y., Zhang J., Liang M., Zhao F., Sun Y. H., Zhang M., Zhou X., Chen Y., et al. (2016) The exome sequencing identified the mutation in YARS2 encoding the mitochondrial tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase as a nuclear modifier for the phenotypic manifestation of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy-associated mitochondrial DNA mutation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25, 584–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Qian Y., Zhou X., Liang M., Qu J., and Guan M. X. (2011) The altered activity of complex III may contribute to the high penetrance of Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy in a Chinese family carrying the ND4 G11778A mutation. Mitochondrion 11, 871–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. James A. M., Sheard P. W., Wei Y. H., and Murphy M. P. (1999) Decreased ATP synthesis is phenotypically expressed during increased energy demand in fibroblasts containing mitochondrial tRNA mutations. Eur. J. Biochem. 259, 462–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Guan M. X. (2004) Molecular pathogenetic mechanism of maternally inherited deafness. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1011, 259–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lenaz G., Baracca A., Carelli V., D'Aurelio M., Sgarbi G., and Solaini G. (2004) Bioenergetics of mitochondrial diseases associated with mtDNA mutations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1658, 89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hayashi G., and Cortopassi G. (2015) Oxidative stress in inherited mitochondrial diseases. (2015). Free Radic. Biol. Med. 88, 10–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Schieber M., and Chandel N. S. (2014) ROS function in redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr. Biol. 24, R453–R462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Raimundo N., Song L., Shutt T. E., McKay S. E., Cotney J., Guan M. X., Gilliland T. C., Hohuan D., Santos-Sacchi J., and Shadel G. S. (2012) Mitochondrial stress engages E2F1 apoptotic signaling to cause deafness. Cell 148, 716–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tischner C., Hofer A., Wulff V., Stepek J., Dumitru I., Becker L., Haack T., Kremer L., Datta A. N., Sperl W., Floss T., Wurst W., Chrzanowska-Lightowlers Z., De Angelis M. H., Klopstock T., et al. (2015) MTO1 mediates tissue specificity of OXPHOS defects via tRNA modification and translation optimization, which can be bypassed by dietary intervention. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 2247–2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mackerell A. D. Jr., Feig M., and Brooks C. L. 3rd (2004), Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1400–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Essmann U., Perera L., Berkowitz M. L., Darden T., Lee H., and Pedersen L. G. (1995) A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sathiamoorthy S., and Shin J. A. (2012) Boundaries of the origin of replication: creation of a pET-28a-derived vector with p15A copy control allowing compatible coexistence with pET vectors. PLoS One 7, e47259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. King M. P., and Attardi G. (1993) Post-transcriptional regulation of the steady-state levels of mitochondrial tRNAs in HeLa cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 10228–10237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.