Abstract

25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 [25(OH)D3] has recently been found to be an active hormone. Its biological actions are demonstrated in various cell types. 25(OH)D3 deficiency results in failure in bone formation and skeletal deformation. Here, we investigated the effect of 25(OH)D3 on osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs). We also studied the effect of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,25-(OH)2D3], a metabolite of 25(OH)D3. One of the vitamin D responsive genes, 25(OH)D3-24-hydroxylase (cytochrome P450 family 24 subfamily A member 1) mRNA expression is up-regulated by 25(OH)D3 at 250–500 nM and by 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at 1–10 nM. 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at a time-dependent manner alter cell morphology towards osteoblast-associated characteristics. The osteogenic markers, alkaline phosphatase, secreted phosphoprotein 1 (osteopontin), and bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein (osteocalcin) are increased by 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in a dose-dependent manner. Finally, mineralisation is significantly increased by 25(OH)D3 but not by 1α,25-(OH)2D3. Moreover, we found that hMSCs express very low level of 25(OH)D3-1α-hydroxylase (cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1), and there is no detectable 1α,25-(OH)2D3 product. Taken together, our findings provide evidence that 25(OH)D3 at 250–500 nM can induce osteogenic differentiation and that 25(OH)D3 has great potential for cell-based bone tissue engineering.

1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [calcitriol, 1α,25-(OH)2D3] is generated through two sequential hydroxylation steps of vitamin D3 in the body. The first step is 25-hydroxylation producing 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 [calcidiol, 25(OH)D3] in the liver, and the second step is 1α-hydroxylation mediated by 25(OH)D3-1α-hydroxylase, also called cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1, (CYP27B1, encoded by the gene CYP27B1) in the kidney1. 1α,25-(OH)2D3 exerts its actions via a nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR) and is regarded as the most active form of vitamin D. Since the discovery of CYP27B1 in extra-renal tissues, the intracellular production of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 from 25(OH)D3 has been suggested to play an autocrine or a paracrine role in the local regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation2,3.

25(OH)D3 is the most abundant vitamin D metabolite in the blood. Its deficiency causes rickets in children and osteomalacia in adults4. Osteoporosis and fracture are also closely related to the suboptimal status of 25(OH)D35,6,7,8. Recent studies have demonstrated that 25(OH)D3 at physiological concentrations is as potent as 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at pharmacological concentrations in terms of regulating the behaviour of various types of cells both in vitro and in vivo9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20.

Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) can differentiate towards several cell lineages including osteoblasts, adipocytes, chondrocytes, and muscle cells21. They are a good cell source for tissue engineering and a good model for the study of hormonal effects. The osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs has been extensively studied since it could be a potential cell source for the treatment of bone defects, bone loss, and osteoporosis. 1α,25-(OH)2D3 has been shown to induce the osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs22,23, but there is not much information about the effects of 25(OH)D3 on these processes. In the present study, we evaluated the actions of 25(OH)D3 during osteogenesis of hMSCs in many aspects including cellular morphology, osteoblast-related gene expression, protein secretion, and mineralisation. These findings can be further exploited for bone tissue engineering applications.

Results

The concentrations of 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 used in the present study were chosen according to their optimal physiological concentrations. The optimal serum concentration of 25(OH)D3 is still under discussion. A serum level of 25(OH)D3 between 75–150 nM can be considered vitamin D sufficiency4. The Institute of Medicine recommends the optimal concentration of 25(OH)D3 being 50 nM, International Osteoporosis Foundation recommends 75 nM or above, MedlinePlus recommends 75–185 nM, and the Endocrine Society recommends 100 nM. We have used 100–500 nM that are no more than ~3 folds higher than the recommended optimal serum concentrations. On the other hand, the serum level of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 is strictly controlled between 0.03–0.14 nM24. We have used 0.05–10 nM that are no more than ~70 folds higher than the physiological concentrations.

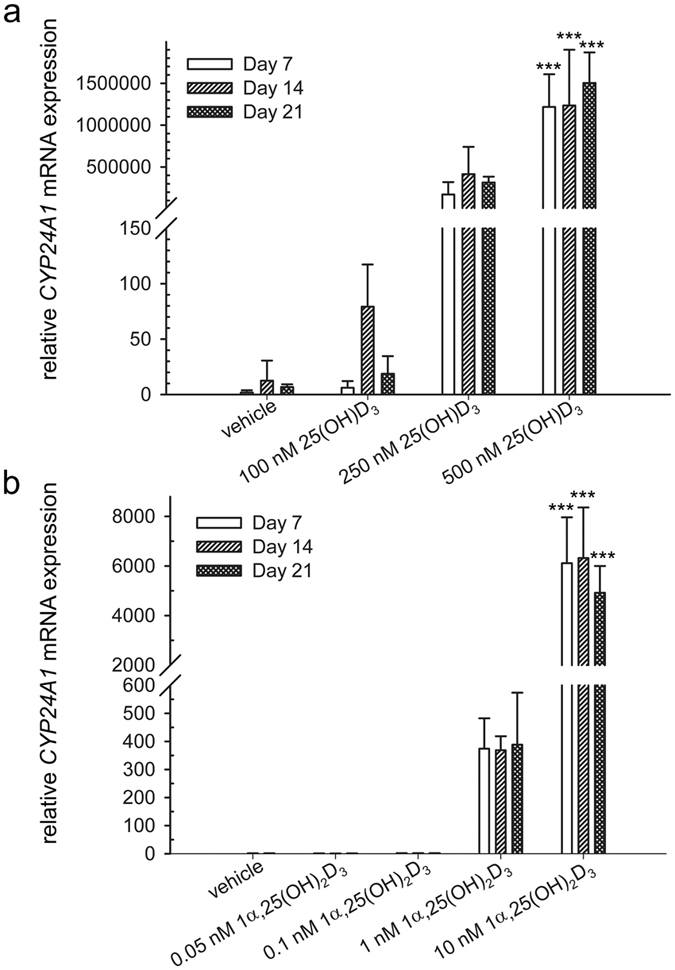

Effect of 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on 24-hydroxylase in hMSCs

To investigate the osteogenic differentiation effects of vitamin D metabolites on hMSCs, we first ensured that hMSCs were responsive to vitamin D treatments. 24-Hydroxylase, cytochrome P450 family 24 subfamily A member 1, encoded by the gene CYP24A1, is regulated by the ligand-bound vitamin D receptor. It has been regarded as one of the most vitamin D-responsive genes. Earlier microarray studies showed that CYP24A1 was the most upregulated gene by 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 among 38500 human genes20 and by 1α,25-(OH)2D3 among 3800 human genes25. We therefore used its mRNA expression as an indicator of the responsiveness of hMSCs to vitamin D.

500 nM 25(OH)D3 significantly increased the level of CYP24A1 mRNA 1217591 ± 389680 folds (P < 0.001), 1234651 ± 666181 folds (P < 0.001), and 1503721 ± 364941 folds (P < 0.001) at day 7, 14, and 21, respectively (Fig. 1a). 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 significantly increased the level of CYP24A1 mRNA 6113 ± 1851 folds (P < 0.001), 6321 ± 2042 folds (P < 0.001), and 4918 ± 1082 folds (P < 0.001) at day 7, 14, and 21, respectively (Fig. 1b). Lower concentrations of 25(OH)D3 (250 nM) and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (1 nM) also increased the gene expression of CYP24A1, but the increase was not statistically significant. This result demonstrates the transcriptional activity of 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in hMSCs and suggests that hMSCs respond to vitamin D treatments.

Figure 1. Induction of cytochrome P450 family 24 subfamily A member 1 (CYP24A1) by 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in hMSCs.

Real-time quantitative PCR was used to determine the induction of CYP24A1 mRNA in response to 25(OH)D3 (a) and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (b) at the indicated concentrations in the hMSCs during three weeks of treatment. Relative mRNA expression was normalised to the control gene ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (RPLP0) and fold inductions were calculated in reference to solvent control (0.1% ethanol), which is set as 1. Results are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3, ***P < 0.001).

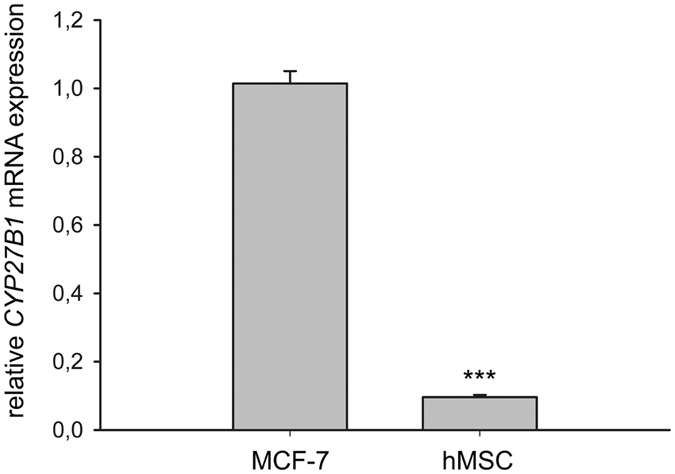

CYP27B1 gene expression and 1α-hydroxylation in hMSCs

25(OH)D3 is metabolised into 1α,25-(OH)2D3 by 1α-hydroxylase, cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1, encoded by CYP27B1. To clarify whether this occurs in hMSCs, we first measured the mRNA expression of CYP27B1. MCF-7 cell line was selected as a positive control as it is well-established in the literature26,27. The hMSCs expressed extremely low level of CYP27B1 mRNA, approximately 9.5% of the level expressed in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 2). In addition, 1α,25-(OH)2D3 was not detectable by HPLC in the conditioned media of hMSCs treated with 500 nM 25(OH)D3 (data not shown). We noticed that the cycle threshold (Ct) values of CYP24A1 were higher than those of CYP27B1 and a housekeeping gene ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (RPLP0) in hMSCs untreated with vitamin D metabolites (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 2. Cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1 (CYP27B1) mRNA expression.

Real-time quantitative PCR was used to determine the expression of CYP27B1 mRNA in the hMSCs. Relative mRNA expression was normalised to the control gene ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (RPLP0). Results are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3, ***P < 0.001).

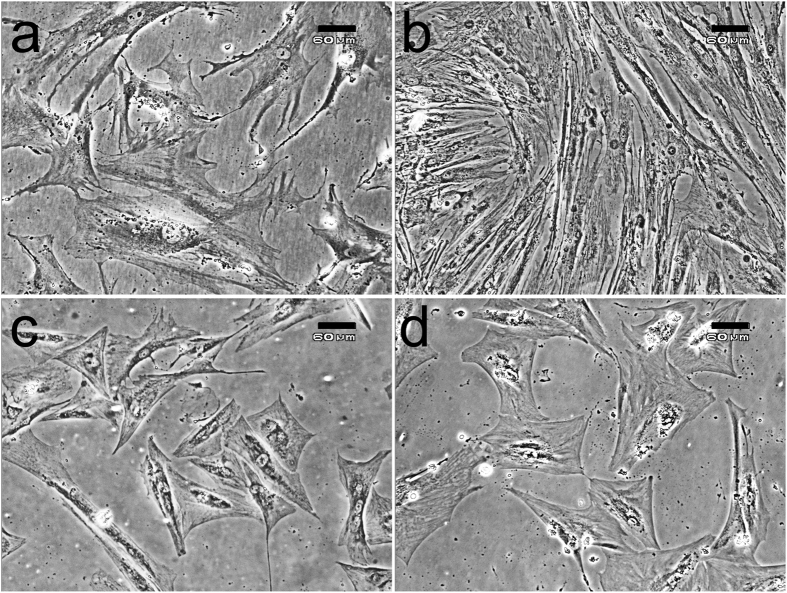

Morphological change of hMSCs during the treatment with 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3

To test the hypothesis that 25(OH)D3 might play a role in osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs, we first monitored the morphological changes of the hMSCs upon the treatment with 25(OH)D3. The hMSCs cultured at a lower density in normal growth medium appeared to be big, flat, and spindle-shaped (Fig. 3a); and at a higher density after 21-day culture they looked more fibroblast-like (Fig. 3b). In the presence of 500 nM 25(OH)D3, some cells started to change their morphology as early as day 6 and appeared more polygonal, an osteoblast-associated characteristic. After 16 days in culture in the presence of 500 nM 25(OH)D3, the cells comprised a relatively homogeneous population of polygonal cells. Figure 3c shows a dramatic change in cell morphology in the culture treated with 500 nM 25(OH)D3 for 21 days. The morphological change was observed to a lesser extent in the culture treated with 250 nM 25(OH)D3 for 21 days (data not shown). In the presence of 100 nM 25(OH)D3 for 21 days, the cells seemed to be morphologically similar to the untreated hMSCs (data not shown).

Figure 3. Morphological changes of hMSCs during the treatments with 25(OH)D3 or 1α,25-(OH)2D3.

(a) hMSCs at day 0; (b) 0.1% ethanol-treated hMSCs at day 21; (c) 500 nM 25(OH)D3-treated hMSCs at day 21; (d) 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3-treated hMSCs at day 21. Scale bars: 60 μm.

Similarly, some of the hMSCs started to exhibit morphological change after 7-day treatment with 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3. At day 21 (Fig. 3d), the cells looked the same as those treated with 500 nM 25(OH)D3. 1 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 caused similar morphological change starting at day 14. 1α,25-(OH)2D3 lower than 1 nM did not change cell morphology.

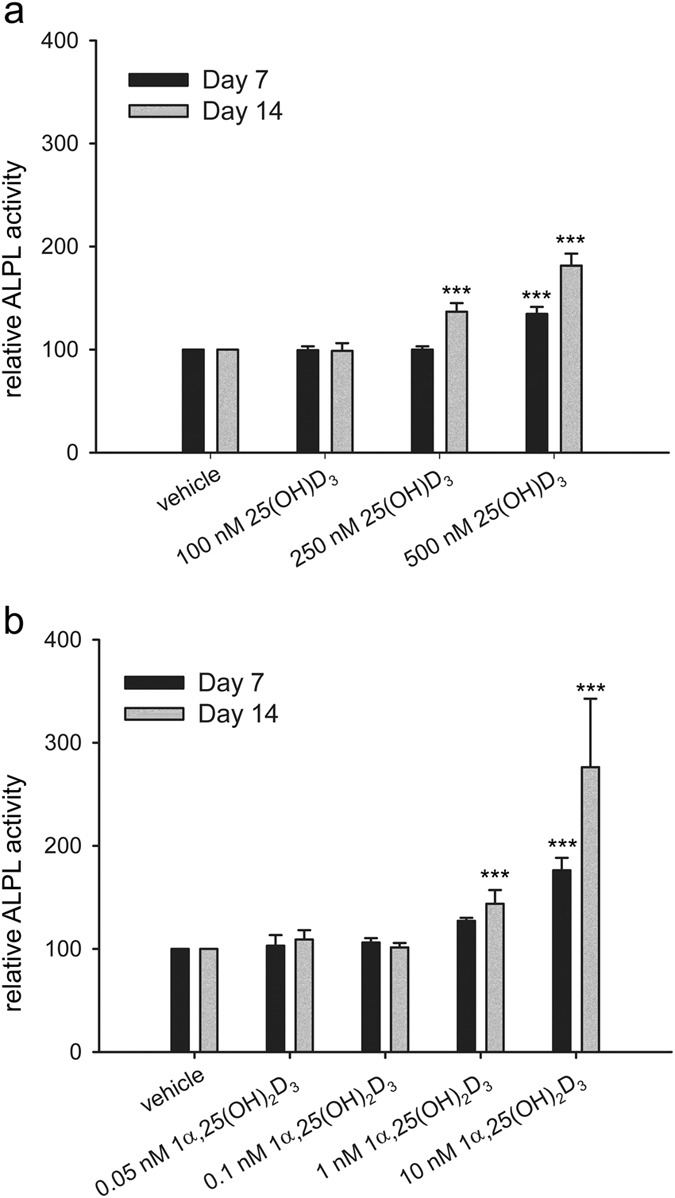

25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 increase the activity of alkaline phosphatase (ALPL) in hMSCs

To characterize the derived cell type, we first measured ALPL activity, which is an early marker expressed during osteogenesis. ALPL activity was measured immediately at each time point. Due to possible variations in fluorescence signals between measurements, we can compare readings only between treatments at the same time point, but not between different time points. To compare the changes in the ALPL activity between time points, we present the results as relative ALPL activity in reference to vehicle control at each time point. Compared with the vehicle control, ALPL activity of the hMSCs treated with 500 nM 25(OH)D3 for 7 days was 135 ± 7% (P < 0.001, Fig. 4a). ALPL activity of hMSCs treated with 250 nM and 500 nM 25(OH)D3 for 14 days was 137 ± 8% (P < 0.001) and 182 ± 12% (P < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 4a). 100 nM 25(OH)D3 did not change ALPL activity.

Figure 4. Regulation of ALPL activity by 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in hMSCs.

Alkaline phosphatase (ALPL) activity was measured according to the procedure of ELF97 in the hMSCs during two weeks of treatments with 25(OH)D3 (a) or 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (b) at the indicated concentrations. Results are expressed as means ± SD (n = 9, ***P < 0.001).

We also studied the effect of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on ALPL activity. 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 increased ALPL activity to 176 ± 12% (P < 0.001) at day 7 (Fig. 4b). After 14 days 1 nM and 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 increased ALPL activity to 144 ± 13% (P < 0.001) and 276 ± 66% (P < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 4b). 0.05 nM and 0.1 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 did not change ALPL activity.

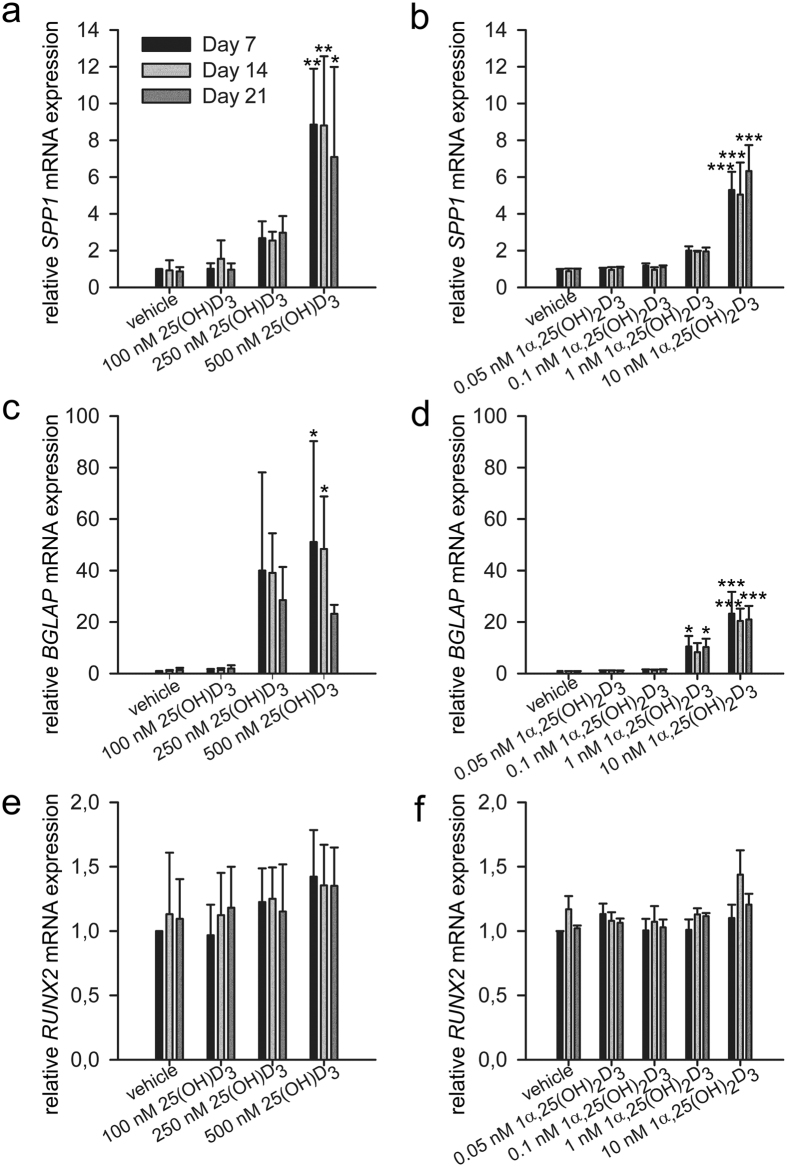

Effects of 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on the expression of osteoblast-related genes

We next examined the effects of 25(OH)D3 on the expression of osteoblast-related genes. Secreted phosphoprotein 1, also called osteopontin, encoded by SPP1, was upregulated by 500 nM 25(OH)D3 by 8.9 ± 3.0 folds (P = 0.001), 8.8 ± 3.8 folds (P = 0.001), and 7.1 ± 4.9 folds (P = 0.012) at day 7, 14, and 21, respectively (Fig. 5a). More importantly, the only osteoblast-specific gene, bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein, also called osteocalcin, encoded by BGLAP, was significantly increased by 51.1 ± 39.1 folds (P = 0.023) and 48.4 ± 20.4 folds (P = 0.033) by 500 nM 25(OH)D3 at day 7 and 14, respectively (Fig. 5c). Runt related transcription factor 2, encoded by RUNX2, is an osteoblast-related transcription factor28,29,30. RUNX2 is expressed in both untreated and hormone-treated hMSCs and its expression was unaltered by 25(OH)D3 (Fig. 5e). To determine whether 25(OH)D3 affects post-transcription of RUNX2, we analysed the protein expression in hormone-treated hMSCs by Western blotting and found no change compared with untreated hMSCs (data not shown).

Figure 5. Gene regulation by 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 during the osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs.

Real-time quantitative PCR was used to determine the induction of secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) (a,b), bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein (BGLAP) (c,d), and runt related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) (e,f) mRNA in response to the indicated concentrations of 25(OH)D3 or 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in the hMSCs during three weeks of treatments. Relative mRNA expression was normalised to the control gene ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (RPLP0) and fold inductions were calculated in reference to vehicle control, which is set as 1. Results are expressed as means ± SD (n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001).

1α,25-(OH)2D3 showed similar gene regulation pattern despite the different effective concentrations. 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 caused 5.3 ± 1.0-fold (P < 0.001), 5.0 ± 1.7-fold (P < 0.001), and 6.3 ± 1.4-fold (P < 0.001) increase in SPP1 mRNA expression at days 7, 14, and 21, respectively (Fig. 5b). BGLAP was increased 10.5 ± 4.1 folds (P = 0.015) and 10.3 ± 3.2 folds (P = 0.017) by 1 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at days 7 and 21, respectively (Fig. 5d). 10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 caused 23.2 ± 8.5-fold (P < 0.001), 20.4 ± 4.8-fold (P < 0.001), and 21.0 ± 5.3-fold (P < 0.001) increase in osteocalcin mRNA expression at days 7, 14, and 21, respectively (Fig. 5d). Again, RUNX2 mRNA expression was unaltered by 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (Fig. 5f).

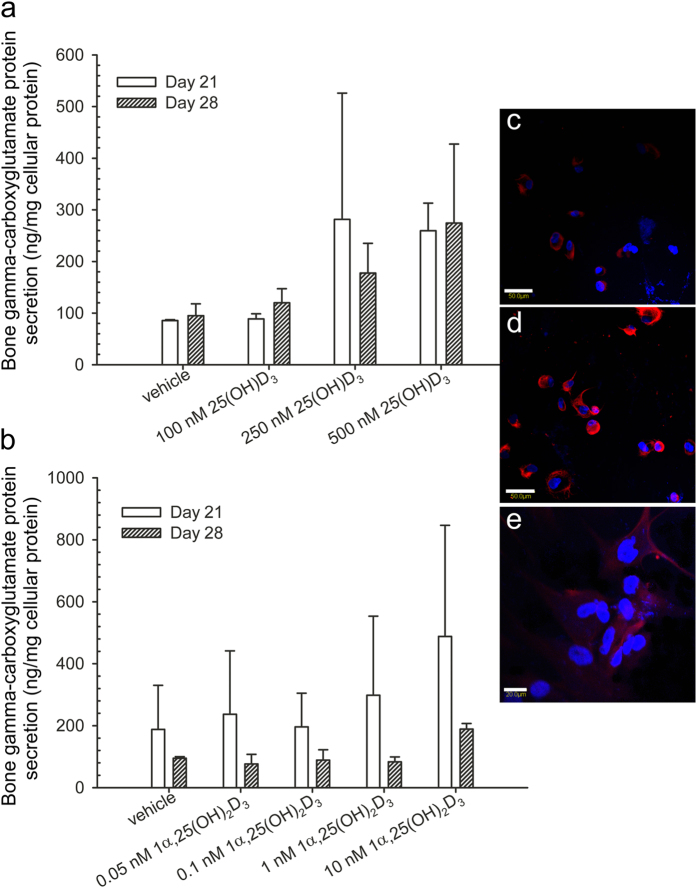

Effects of 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on the expression and secretion of osteocalcin protein in hMSCs

Bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein, a vitamin K-dependent amino acid γ-carboxyglutamic acid, is produced exclusively in osteoblasts and its dental counterpart, the odontoblast. Therefore, the level of bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein is considered as an indicator of cell activity in bone formation. It has a high affinity to calcium and plays an important role in mineralization31,32,33. To measure the secretion of bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein, we used ELISA to measure its concentration in the cell culture medium. Compared with the solvent controls, 250 nM 25(OH)D3 at 250–500 nM and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at 1–10 nM modestly increased bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein secretion, but the increase is not statistically significant due to a low power (Fig. 6a,b). In addition, the intracellular expression of bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein seemed to increase by 25(OH)D3 (Fig. 6d) and modestly by 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (Fig. 6e).

Figure 6. Regulation by 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein secretion and intracellular expression in hMSCs.

(a,b) Bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein secretion in culture media of hMSCs was measured according to the procedure of the Gla-type osteocalcin EIA kit during four weeks of treatments with 25(OH)D3 or 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at the indicated concentrations. Results are expressed as means ± SD. For 25(OH)D3 n = 3 and for 1α,25-(OH)2D3 n = 2. (c–e) Intracellular bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein staining was performed in 0.1% ethanol-treated hMSCs (c), 500 nM 25(OH)D3-treated hMSCs (d), and 1 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3-treated hMSCs (e). Scale bars: 50 μm in c and d, 20 μm in e. Controls in which the primary antibody was replaced with non-immunised mouse IgG show no positive staining (data not shown).

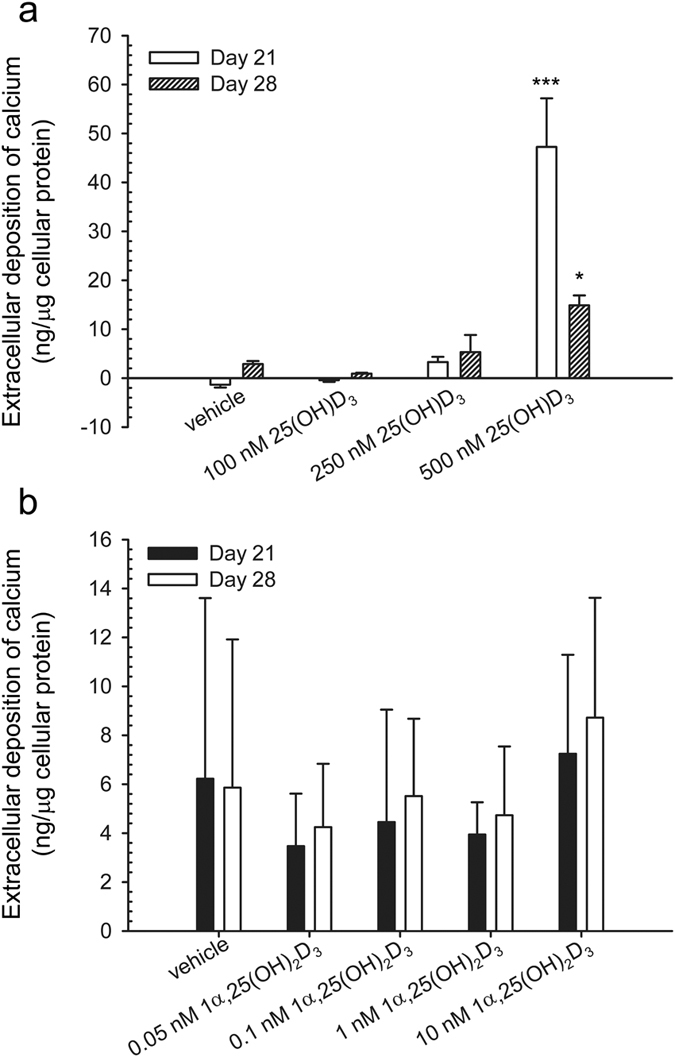

Effects of 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 on the matrix mineralisation in hMSCs

Mineralisation is regarded as a determinant marker for bone formation. Most studies have used von kossa staining to indicate in vitro mineralisation; however, this method has been questioned on its specificity to calcium34. Here, we directly measured calcium concentration in the extracellular matrix. In the presence of 500 nM 25(OH)D3, calcium concentration (ng/μg cellular protein) was 47.2 ± 9.9 (P < 0.001) and 14.9 ± 2.0 (P < 0.05) at days 21 and 28, respectively (Fig. 7a). In contrast, 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at all the concentrations tested did not have any statistically significant effect on the calcium deposition in the extracellular matrix at days 21 and 28 (Fig. 7b) due to a low statistic power.

Figure 7. Mineralisation of the extracellular matrix of hMSCs.

Mineralisation was determined by measuring the extracellular deposition of calcium in response to the treatment with 25(OH)D3 or 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at indicated concentrations during four weeks. Results are expressed as means ± SD (n = 2, *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001).

Discussion

For hMSC-based therapy to be successful in in vivo treatment of bone diseases, it is crucial to transplant hMSCs with a suitable substance that facilitates their osteogenic differentiation in vivo. Although 1α,25-(OH)2D3 had previously been demonstrated to be efficient in inducing some osteogenic lineage markers in hMSCs, the potential side effects induced by the usage of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at pharmacological concentrations are major drawbacks for its in vivo use. This motivated us to evaluate the use of 25(OH)D3 as it has been recognised as an active metabolite in various systems.

Our present study demonstrates that 25(OH)D3 is able to induce osteogenesis of hMSCs and offers a potential approach to bone tissue engineering and treatment of bone diseases. 25(OH)D3 at 250–500 nM and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at 1–10 nM caused morphological change towards osteoblast-associated characteristics and increased the expression of osteogenic markers. Compared with 1α,25-(OH)2D3, the differentiation-inducing effect of 25(OH)D3 was greater given that calcium deposition in the extracellular matrix of 25(OH)D3-treated hMSCs was significantly increased. We found that both mRNA and protein expression of RUNX2 was unaltered in the presence of 25(OH)D3 or 1α,25-(OH)2D3. Earlier studies showed that RUNX2 expression was not regulated by 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in human osteoblasts35 and upregulated by 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in human marrow stromal cells3. The discrepancy may reflect a cell type-specific response of RUNX2 to vitamin D. Both RUNX2 and bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein exhibit a species-specific response to vitamin D, being inhibited by 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in mouse28,36,37. In contrast, 1α,25-(OH)2D3 directly induces human bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein via a vitamin D responsive element38,39, and its action is not mediated by RUNX2 in human osteoblasts40.

Whether the osteogenic effect of 25(OH)D3 on hMSCs is direct or indirect via its metabolites requires an in-depth analysis. We and others have shown that 25(OH)D3 is an active hormone without being converted into 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in various types of cells and also in vivo9,10,11,12,13,14,16,17,41. In addition, a 25(OH)D3 analogue that cannot be 1α-hydroxylated exhibits anti-proliferative activity18. Our systematic study of global gene expression clarifies distinct roles of 25(OH)D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 and also reveals the direct genomic action of 25(OH)D3 by using CYP27B1 knockout cells20. In this study, the osteogenesis-stimulating effect of 25(OH)D3 is presumably not mediated by 1α,25-(OH)2D3 produced by hMSCs because the mRNA expression of CYP27B1 in the hMSCs was very low and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 could not be detected in the conditioned media. It should be noted that our data do not indicate the absence of CYP27B1 in hMSCs. The HPLC method we used to measure 1α,25-(OH)2D3 may have a low sensitivity since it used a UV detector. In earlier studies using radioimmunoassay or enzyme immunoassay, 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at pM was detected after treatment with 1000 nM 25(OH)D3, and the authors suggested that the action of 25(OH)D3 was mediated by CYP27B1 enzyme2,3. However, 1–10 nM 1α,25-(OH)2D3 is required to exert biological effects in vitro. It is possible that intracellular concentration of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 is high enough to induce biological effect. Altogether, the added 25(OH)D3 and cell-produced 1α,25-(OH)2D3 together regulate cell proliferation and differentiation.

We found that 25(OH)D3 at 250–500 nM and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 at 1–10 nM increased the mRNA expression of CYP24A1, which suggests a possibility that the resulting 24 R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 [24 R,25-(OH)2D3] and probably also 1α,24 R,25-trihydroxyvitamin D3 [1α,24 R,25-(OH)3D3] could play a role in osteogenesis. Indeed, both 24 R,25-(OH)2D3 and 1α,24 R,25-(OH)3D3 have been shown to induce osteogenic differentiation of either human osteoblasts42,43 or hMSCs44. The induction of the extracellular matrix mineralisation by 25(OH)D3, but not by 1α,25-(OH)2D3 found in this study is in agreement with an earlier report44. It is tempting to imagine that CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 enzymes are competing for the same substrate 25(OH)D3 in hMSCs. As CYP24A1 was highly upregulated by 25(OH)D3 and both 24 R,25-(OH)2D3 and 1α,25-(OH)2D3 were shown to inhibit CYP27B144,45, it could be reasonable to conclude that 1α,25-(OH)2D3 produced in hMSCs, if any, may play a minor role in osteogenesis.

The use of 25OHD3 shows several advantages over 1α,25-(OH)2D3 in both in vivo and ex vivo applications. Firstly, cell uptake of 25(OH)D3 is supposed to be greater than that of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 due to the higher hydrophobicity of 25(OH)D3. Additionally, megalin-mediated endocytosis of 25(OH)D3-vitamin D binding protein complex is an important mechanism for cell uptake of 25(OH)D3 in many tissues and cells, including osteoblasts2,46. Secondly, 25(OH)D3 is more stable than 1α,25-(OH)2D3. The half-life of 25(OH)D3 in the circulation is about two-three weeks while that of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 is only less than four hours47,48,49,50. Since osteogenesis is not a fast process, stable vitamin D metabolite is preferable especially for in vivo applications. Thirdly, the present study shows that the osteogenesis-inducing concentration of 25(OH)D3 is between 250–500 nM, which is well accepted in ex vivo applications and may even be tolerable in some in vivo applications as no significant rise in serum calcium was observed when 25(OH)D3 level was above 500 nM in healthy men51. The literature data and controlled dosing studies have confirmed that no vitamin D toxicity occurs at serum 25(OH)D3 levels below 500 nM52,53. In contrast, the osteogenesis-inducing concentration of 1α,25-(OH)2D3 is 1–10 nM, which is much higher than its physiological levels (0.03–0.14 nM)24. It is worth noting that, here, we can only compare the osteogenesis-inducing concentrations of vitamin D metabolites with their serum concentrations since their tissue concentrations are unknown. Their tissue and intracellular concentrations are likely different from their serum concentrations when considering vitamin D metabolism and transport in target cells. Furthermore, we show here that the extracellular matrix mineralisation was induced by 25(OH)D3 but not by 1α,25-(OH)2D3. 25(OH)D3, despite its lower affinity to VDR, can stabilise the VDR-ligand binding domain in its agonistic conformation in the same way as 1α,25-(OH)2D3 does12. Collectively, 25(OH)D3 exhibits more potent bone anabolic effects but less side effects particularly for clinical bone tissue engineering, in which cell-scaffold constructs accompanied with osteogenesis stimulating factors are implanted in an in vivo environment.

In conclusion, we demonstrate here that 25(OH)D3 at 250–500 nM induces osteogenesis of hMSCs. The finding improves our understanding of the relationship between vitamin D and bone health. Our finding may also contribute to clinical bone tissue engineering.

Methods

Cell culture

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were obtained from Lonza (Walkersville, MD, USA). Cells were cultured and maintained in mesenchymal stem cell growth medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells at passage 5 were used in the present study.

Differentiation of hMSCs

The hMSCs were plated in multiple-well plates at a density of 3000 cells/cm2 for one day to allow attachment in mesenchymal stem cell growth medium. At day 0, the medium was changed to osteogenic medium containing β-glycerophosphate and ascorbate-2-phosphate as supplied by the manufacturer, and supplemented with either 25(OH)D3 or 1α,25-(OH)2D3 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louise, MO, USA) dissolved in ethanol at the concentrations indicated. The final concentration of ethanol in the culture medium was 0.1% in both hormone-treated cultures and vehicle controls. The medium was renewed three times a week.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Cells were cultured and differentiated in 6-well plates for 7, 14, and 21 days. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at each time point during differentiation experiments. The TRIzol samples were stored at −80 °C for up to one month and were undergone the subsequent extraction procedure following the manufacturer’s instructions. All the RNA samples were converted into cDNA at the same experiment after day 21 to ensure the same reverse transcription efficiency. The cDNA synthesis was performed by using Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). All the cDNA samples were analysed in duplicate by real-time PCR in the same runs. For each gene, a standard curve with R2 greater than 0.996 was generated. This was not only to ensure that the unknown samples were within the standard range, but also to obtain the amplification efficiency for calculating the fold inductions as described previously54. PCR product quality was monitored using post-PCR dissociation curve analysis. All primers were synthesised by Research Biolabs, Singapore. The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Primer sequences.

| Gene name | Forward primer | Reverse primer | qPCR Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human secreted phosphoprotein 1, also called osteopontin (SPP1, NM_000582.2, NM_001040060.1, and NM_001040058.1) | 5′-GAGGGCTTGGTTGTCAGC-3′ | 5′-CAATTCTCATGGTAGTGAGTTTTCC-3′ | LightCycler 1.5 |

| Human ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (RPLP0, NM_053275.3 and NM_001002.3) | 5′-ACAGGGCGACCTGGAAGT-3′ | 5′-GGATCTGCTGCATCTGCTT-3′ | LightCycler 1.5 |

| Human cytochrome P450 family 24 subfamily A member 1 (CYP24A1, NM_000782) | 5′-GCCCAGCCGGGAACTC-3′ | 5′-AAATACCACCATCTGAGGCGTATT-3′ | ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system |

| Human runt related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2, NM_001015051.2, NM_001024630.2, and NM_004348.3) | 5′-CGTGGCCTTCAAGGTGGTA-3′ | 5′-CGGAGCTCAGCAGAATAATTTTC-3′ | ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system |

| Human bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein (BGLAP, NM_199173) | 5′-AGCAAAGGTGCAGCCTTTGT-3′ | 5′-GGCTCCCAGCCATTGATACA-3′ | ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system |

| Human ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (RPLP0, NM_053275 and NM_001002) | 5′-AATCTCCAGGGGCACCATT-3′ | 5′-CGCTGGCTCCCACTTTGT-3′ | ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system |

| Human cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1 (CYP27B1, NM_000785) | 5′-TTGGCAAGCGCAGCTGTAT-3′ | 5′-TGTGTTAGGATCTGGGCCAAA-3′ | ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system |

The expression of secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1) mRNA was measured using a FastStart DNA MasterPlus SYBR Green I kit on a LightCycler 1.5 (Roche) using the following protocol: 600 s preincubation at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 10 s denaturation at 95 °C, 3 s annealing at 59 °C for SPP1 or at 54 °C for ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0 (RPLP0), and 6 s extension at 72 °C for SPP1 or 5 s for RPLP0.

The expression of cytochrome P450 family 24 subfamily A member 1 (CYP24A1), bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein (BGLAP), and runt related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) mRNA was measured using a Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI Prism 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The expression of cytochrome P450 family 27 subfamily B member 1 (CYP27B1) mRNA was measured using a Fast SYBR Green Master Mix kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) on an ABI Prism 7500 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). The PCR cycling conditions were: 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 1 min annealing/extension at 60 °C.

Quantitative alkaline phosphatase activity measurement

Alkaline phosphatase (ALPL) activity was measured according to the procedure of an ELF97 Endogenous Phosphatase Detection Kit (Molecular Probes, Oregon, USA) in a 96-well plate format. At day 7 and day 14, cells grown on 96-well plates were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and then permeabilised with 0.2% Tween 20 in PBS for 15 min. After rinsing with distilled water twice, the cells were incubated with the ELF 97 phosphatase substrate in the detection buffer (1:20, 50 μl/well) for 5 min in the dark. The fluorescence of the resulting product was directly measured by fluorescence spectroscopy (Tecan Safire II, Grödig, Austria) at an excitation wavelength of 345 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm. The cells were then washed with distilled water twice. The total cellular protein was extracted by 50 μl of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate per well and was stored at −80 °C. The protein concentration was measured by a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The ALPL activity was normalised against the total cellular protein concentration and expressed as relative levels against the solvent control.

ELISA assay

Cells were cultured and differentiated in 6-well plates for 7, 14, 21, and 28 days. At each time point, the conditioned media were collected and stored in aliquots at −80 °C for the subsequent determinations of bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein. The cells were washed once with PBS and lysed with a RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The cell lysates were stored in aliquots at −80 °C for the subsequent measurements of protein concentration and immunoblotting of RUNX2 protein. After day 28, all the conditioned media were diluted 1 to 10 in the sample diluents provided by a Gla-type osteocalcin EIA kit and analysed in duplicate by the Gla-type osteocalcin EIA kit (Zymed Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufactures’ protocol. The readings of the samples in the ELISA measurement were within the range of the standards (0–16 ng/ml). The protein concentrations in the cell lysates were measured in duplicate by a BCA protein assay kit. Subsequently the cell lysates were used in immunoblotting of RUNX2. The bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein concentrations were normalised against the cellular protein concentration and expressed as ng bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein per mg cellular protein.

Mineralisation

Mineralisation was determined by measuring the extracellular deposition of calcium. Cells were cultured and differentiated in 12-well plates for 7, 14, 21, and 28 days. At each time point, cell culture media were removed and cells were washed with calcium-free DPBS twice followed by decalcification in 0.4 ml of 0.6 N hydrochloric acid per well for 24 h at 4 °C. The resulting extracts in hydrochloric acid were centrifuged at 2000 g for 10 min, and the supernatants were stored at −20 °C. After day 28, calcium concentrations in hydrochloric acid supernatants were directly measured in duplicate using a Stanbio Total Calcium LiquiColor kit (STANBIO Laboratory, Boerne, TX, USA). According to the manufacturer’s instruction, a standard was included in every measurement. In the first time, calibration was done by making a 3-point-standard curve to verify the linearity.

After 24 h incubation with hydrochloric acid, the decalcified cell monolayers were washed with DPBS three times. The cellular protein was extracted with 0.2 ml of 0.1 N sodium hydroxide in 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate per well and stored at −80 °C. The protein concentrations were measured in duplicate by a BCA protein assay kit. The results were expressed as ng calcium per μg cellular protein.

Immunoblotting

Cell lysates were obtained from the 6-well plates that were used in ELISA assays. Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA protein assay kit. Cell lysates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using a 10% gel. Protein bands were transferred to hybond-P PVDF transfer membranes (0.45 μm pore; Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfont, UK). After blocking of nonspecific binding sites with a SuperBlock blocking buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) at room temperature for 2 h, the membranes were incubated with goat-anti-human RUNX2 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:500 at 4 °C overnight. After being washed with TBS-0.1% Tween 20, the membranes were incubated with donkey-anti-goat horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) at a 1:10000 dilution at room temperature for 1 h. The blots were detected by ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and exposed to x-ray film for 1 min.

Immunofluorescence

After differentiation, cells were cultured on 8-well CultureSlides (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for 4 h and then fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature and thereafter permeabilised with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. After being blocked with 5% normal rabbit serum, the cells were incubated with mouse-anti-human bone gamma-carboxyglutamate protein antibody (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at a dilution of 1:50 at 4 °C overnight. Controls included omission of the primary antibodies and incubating with nonimmunized mouse IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The secondary antibody rabbit-anti-mouse Cy5-conjugated IgG (AbD Serotec, Kidlington, Oxford, UK) was used at room temperature for one hour. All washings using PBS-0.2% Tween 20 were repeated 3 times, 5 min each. The cells were then counterstained with VECTASHIELD mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Staining was viewed under a confocal microscope with a 40x water len (Fluoview 300, Olympus, Japan).

Statistics

Standard deviations were calculated by Microsoft Excel. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparison test (Figs 1, 4 and 7; SigmaPlot 11.0) was performed to determine the significances of differences between hormone-treated samples and solvent controls. Student’s t-test was performed to determine the significance of difference between MCF-7 and hMSC cells (Fig. 2; SigmaPlot 11.0). Differences of P < 0.05 (*), P < 0.01 (**), and P < 0.001 (***) were considered significant.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Lou, Y.-R. et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 induces osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 42816; doi: 10.1038/srep42816 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Institute of Bioengineering and Nanotechnology, Biomedical Research Council, Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) of Singapore and grants R185-001-045-305; R-185-000-135-112 (Ministry of Education), SMART, MBI (R-714-006-008-271), NMRC (R-185-000-294-511), and Singapore-MIT Alliance Computational and Systems Biology Flagship Project funding to H.Y. Y.H.T. is a Graduate Research Scholar of the National University of Singapore. Y.-R.L. acknowledges support from the Academy of Finland (grant No. 294193). We would like to thank Dr. Zhilian Yue for helping in the measurement of vitamin D metabolites by HPLC.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Y.-R.L. and H.Y. designed the study; Y.-R.L., T.C.T., and Y.H.T. carried out the experiments; Y.-R.L. analysed the data; Y.-R.L. and H.Y. wrote the manuscript; all the authors commented on and edited the final version of the paper.

References

- DeLuca H. F. Overview of general physiologic features and functions of vitamin D. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80, 1689S–1696S (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Driel M. et al. Evidence for auto/paracrine actions of vitamin D in bone: 1alpha-hydroxylase expression and activity in human bone cells. FASEB. J. 20, 2417–2419 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng S., Zhou S. & Glowacki J. Effects of 25-hydroxyvitamin D(3) on proliferation and osteoblast differentiation of human marrow stromal cells require CYP27B1/1alpha-hydroxylase. J. Bone Miner. Res. 26, 1145–1153 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick M. F. Vitamin D deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 266–281 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guardia G. et al. Prevalence of vitamin D depletion among subjects seeking advice on osteoporosis: a five-year cross-sectional study with public health implications. Osteoporos. Int. 19, 13–19 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Schoor N. M. et al. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for osteoporotic fractures. Bone 42, 260–266 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B. R. & Shoemaker M. R. Osteoporosis: understanding key risk factors and therapeutic options. Phys. Sportsmed. 28, 69–84 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruohola J. P. et al. Association between serum 25(OH)D concentrations and bone stress fractures in Finnish young men. J. Bone Miner. Res. 21, 1483–1488 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y. R. et al. 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 is an active hormone in human primary prostatic stromal cells. FASEB. J. 18, 332–334 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X., Hawthorne M., Vaishnav A., St-Arnaud R. & Mehta R. G. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 is a natural chemopreventive agent against carcinogen induced precancerous lesions in mouse mammary gland organ culture. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 113, 31–41 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X. et al. Protection against cellular stress by 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in breast epithelial cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 110, 1324–1333 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y. R. et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D(3) is an agonistic vitamin D receptor ligand. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 118, 162–170 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y. R. & Tuohimaa P. Androgen enhances the antiproliferative activity of vitamin D3 by suppressing 24-hydroxylase expression in LNCaP cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 99, 44–49 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter C. S., Armbrecht H. J., Slatopolsky E. & Brown A. J. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D(3) suppresses PTH synthesis and secretion by bovine parathyroid cells. Kidney Int. 70, 654–659 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuohimaa P. & Lou Y. R. Optimal serum calcidiol concentration for cancer prevention. Anticancer Res. 32, 373–381 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. L., Ding X. F., Tong J. & Li B. Y. Partial rescue of the phenotype in 1alpha-hydroxylase gene knockout mice by vitamin D3 injection. Endocr. Res. 36, 101–108 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter C. S. & Brown A. J. Direct suppression of Pth gene expression by the vitamin D prohormones doxercalciferol and calcidiol requires the vitamin D receptor. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 46, 63–66 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munetsuna E. et al. Mechanism of the anti-proliferative action of 25-hydroxy-19-nor-vitamin D(3) in human prostate cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 47, 209–218 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diesel B. et al. Vitamin D(3) metabolism in human glioblastoma multiforme: functionality of CYP27B1 splice variants, metabolism of calcidiol, and effect of calcitriol. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 5370–5380 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuohimaa P. et al. Gene expression profiles in human and mouse primary cells provide new insights into the differential actions of vitamin D3 metabolites. PLoS One 8, e75338 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger M. F. et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284, 143–147 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal N., Haynesworth S. E., Caplan A. I. & Bruder S. P. Osteogenic differentiation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. J. Cell. Biochem. 64, 295–312 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammons J., Ahmed N., El-Sheemy M. & Hassan H. T. The role of BMP-6, IL-6, and BMP-4 in mesenchymal stem cell-dependent bone development: effects on osteoblastic differentiation induced by parathyroid hormone and vitamin D(3). Stem Cells Dev. 13, 273–280 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieth R., Pinto T. R., Reen B. S. & Wong M. M. Vitamin D poisoning by table sugar. Lancet 359, 672 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro K., Abe T., Oue N., Yasui W. & Ryoji M. Characterization of vitamin D-mediated induction of the CYP 24 transcription. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 226, 27–32 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich M. et al. Analysis of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase in normal and malignant breast tissue. Anticancer Res. 26, 2615–2620 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechner D., Bajna E., Adlercreutz H. & Cross H. S. Genistein and 17beta-estradiol, but not equol, regulate vitamin D synthesis in human colon and breast cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 26, 2597–2603 (2006). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducy P., Zhang R., Geoffroy V., Ridall A. L. & Karsenty G. Osf2/Cbfa1: a transcriptional activator of osteoblast differentiation. Cell 89, 747–754 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T. et al. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell 89, 755–764 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto F. et al. Cbfa1, a candidate gene for cleidocranial dysplasia syndrome, is essential for osteoblast differentiation and bone development. Cell 89, 765–771 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto S. K. & Price P. A. Secretion of the vitamin K-dependent protein of bone by rat osteosarcoma cells. Evidence for an intracellular precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 6579–6583 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price P. A. & Baukol S. A. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 increases synthesis of the vitamin K-dependent bone protein by osteosarcoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 255, 11660–11663 (1980). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poser J. W. & Price P. A. A method for decarboxylation of gamma-carboxyglutamic acid in proteins. Properties of the decarboxylated gamma-carboxyglutamic acid protein from calf bone. J. Biol. Chem. 254, 431–436 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonewald L. F. et al. von Kossa staining alone is not sufficient to confirm that mineralization in vitro represents bone formation. Calcif. Tissue Int. 72, 537–547 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M. et al. Expression and regulation of Runx2/Cbfa1 and osteoblast phenotypic markers during the growth and differentiation of human osteoblasts. J. Cell. Biochem. 80, 424–440 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R., Ducy P. & Karsenty G. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits Osteocalcin expression in mouse through an indirect mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 110–116 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. C. et al. Effects of continuous activation of vitamin D and Wnt response pathways on osteoblastic proliferation and differentiation. Bone 41, 87–96 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner S. A., Scott R. A. & Pike J. W. Sequence elements in the human osteocalcin gene confer basal activation and inducible response to hormonal vitamin D3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 4455–4459 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison N. A. et al. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-responsive element and glucocorticoid repression in the osteocalcin gene. Science 246, 1158–1161 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viereck V. et al. Differential regulation of Cbfa1/Runx2 and osteocalcin gene expression by vitamin-D3, dexamethasone, and local growth factors in primary human osteoblasts. J. Cell. Biochem. 86, 348–356 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munetsuna E. et al. Anti-proliferative activity of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 in human prostate cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 382, 960–970 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Driel M. et al. Evidence that both 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 24-hydroxylated D3 enhance human osteoblast differentiation and mineralization. J. Cell. Biochem. 99, 922–935 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meijden K. et al. Primary human osteoblasts in response to 25-hydroxyvitamin D3, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. PLoS One 9, e110283 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis K. M., Aenlle K. K., Roos B. A. & Howard G. A. 24R,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 promotes the osteoblastic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 28, 644–658 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S., LeBoff M. S. & Glowacki J. Vitamin D metabolism and action in human bone marrow stromal cells. Endocrinology 151, 14–22 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins G. J. et al. Metabolism of vitamin D3 in human osteoblasts: evidence for autocrine and paracrine activities of 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Bone 40, 1517–1528 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund B., Sorensen O. H., Lund B., Bishop J. E. & Norman A. W. Vitamin D metabolism in hypoparathyroidism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 51, 606–610 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca H. F. Vitamin D and the parenteral nutrition patient. Gastroenterology 137, S79–91 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boullata J. I. Vitamin D supplementation: a pharmacologic perspective. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 13, 677–684 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick M. F. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 80, 1678S–1688S (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger-Lux M. J., Heaney R. P., Dowell S., Chen T. C. & Holick M. F. Vitamin D and its major metabolites: serum levels after graded oral dosing in healthy men. Osteoporos. Int. 8, 222–230 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaney R. P. Vitamin D: criteria for safety and efficacy. Nutr. Rev. 66, S178–181 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathcock J. N., Shao A., Vieth R. & Heaney R. Risk assessment for vitamin D. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 85, 6–18 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e45 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.