Abstract

Background:

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are often accompanied with comoribidities and complications leading to taking multiple drugs and thus are more liable to be exposed to drug-related problems (DRPs). DRPs can occur at any stages of medication process from prescription to follow-up treatment. However, a few studies have assessed the specific risk factors for occurrence of at least one potential DRP per patient with CVDs in sub-Saharan African region.

Aim:

We aim to assess the risk factors for developing potential DRPs in patients with CVDs attending Gondar University Referral Hospital (GUH).

Methodology:

This was a cross-sectional study. A structured systematic data review was designed focusing on patients with CVDs (both out and inpatients) with age >18 years of both genders attending GUH from April to June 2015. All DRPs were assessed using drugs.com and Medscape. The causes of DRPs were classified using Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe version 6.2. Risk factors that could cause DRPs were assessed using binary logistic regression showing odds ratio with 95% confidential interval. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results:

A total of 227 patients with CVDs were reviewed with a mean age of 52.0 ± 1.7 years. Majority were females (143, 63%), outpatients (133, 58.6%), and diagnosed with heart failure (71, 31.3%). Diuretics (199, 29.5%) were the most commonly prescribed drugs. A total of 265 DRPs were identified, 63.4% of patients have at least one DRP (1.17 ± 1.1). The most common DRPs were found to be an inappropriate selection of drug (36.1%) and dose (24.8%). The most identified risk factors causing DRPs were: Need of additional drug therapy and lack of therapeutic monitoring.

Conclusion:

The most identified risk factors for developing DRPs were the need of additional drug therapy and lack of therapeutic monitoring. There is a need for clinical pharmacist interventions to monitor and prevent the risk of developing DRPs and contribute to improve the clinical outcome in patients with CVDs.

KEY WORDS: Cardiovascular diseases, clinical pharmacist, drug related problems, ethiopia, Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe, risk factors

Currently, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the main noncommunicable conditions accounting for 7–10% hospitalization and 9.2% of total deaths in Africa.[1] CVDs account for at least one million deaths in sub-Saharan Africa[2] and compared to 1990 there has been a predominant increase in age-standard mortality of all causes of CVD mortality of 81% (95% confidential interval [CI] =306.2–351.7), ranging from 7% (95% CI = 7.5–13.7) rise of ischemic heart diseases to a 196% (95% CI = 0.3–0.5) increase in atrial fibrillation.[3] Today, CVD is second only to HIV/AIDs as the leading cause of death in adults over 30.[4,5]

In Ethiopia, CVDs have taken over from HIV as the leading cause of death. More than half of the deaths in its capital city, Addis Ababa are attributed to noncommunicable diseases with females more likely to die from CVDs than men.[6] CVD risk factors such as overweight and physical inactivity are on the rise. This may be attributable to progressive urbanization and adopting a western lifestyle in this region.[7,8,9]

Patients with CVDs, like other chronic diseases, require medication. In recent years, there has been a consistent increase in the number of medications (polypharmacy) used in patients with CVD. Polypharmacy can be defined as concurrent use of multiple medication[10] or use of more drugs than clinically indicated or two or more drugs of the same class to treat same conditions.[11] Four out of five patients with CVD, in a Bangladesh study, took an average of 7.3 different drugs a day.[12] This rise in a number of drugs prescribed has been associated with negative health outcomes some of which include, frequent hospitalization, waste of resources, and different drug-related problems (DRPs).[13,14,15,16]

DRPs is defined as an event or circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with desired health outcomes.[17] DRPs can arise at all stages of medication process from prescription to follow-up treatment.[18] Findings from some studies demonstrated that the frequency of DRPs in CVD patients has been ranging from 30.8% to 78%.[19,20] The prevalence of DRPs in CVD patients correspondents to 4.9% per patients with an incidence rate of 91.7%.[21] Furthermore, multiple medications use poses an increasing risk for developing at least one DRP in patients with CVD. Early identification of these risk factors can improve the patients’ quality of life and prevent potential events.[22] A literature review revealed no results particularly focusing on DRPs in Ethiopian CVD patients. In this regard, we aimed to characterize the occurrence of DRPs and to assess the risk factors for developing potential DRPs in patients with CVDs attending Gondar University Referral Hospital (GUH), Gondar, North-West Ethiopia.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee, University of Gondar, School of Pharmacy, Gondar, Ethiopia. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient to review their medication chart before the data collection.

Methodology

This was a cross-sectional study design conducted from April to June 2015 in Cardiology Unit in GUH. Gondar is a historical city located in North-Western part of Ethiopia, approximately 738 km from the capital city Addis Ababa. GUH is 550 bedded teaching referral hospital treating approximately 201,992 (annually) patients living in and around Gondar.[23] The Cardiology Unit constitutes 18 beds and also provide outpatient services on every Monday of the week. From April 2015, six newly graduated clinical pharmacists were allocated in Cardiology Units (in and outpatients) to provide comprehensive pharmaceutical care. For research purpose, pharmacists were requested to extract and record the drugs used for the patients in Cardiology Unit (in and outpatients) in a separate data collection form at GUH.

Study population

All patients with CVDs who were either admitted to Cardiology Unit or visiting outpatient clinics on Mondays, met the inclusion criteria and willing to participate in the study were followed up by six clinical pharmacists.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Ethiopian patients, ≥18 years, both genders, inpatients and outpatients, attending Cardiology Unit, using mainly cardiovascular medications were included in the study. CVD patients attending emergency ward and re-admitted during the study were excluded from the study.

Data collection

A specially designed data collection from was used to collect the data for the research purpose and the following data were collected: Sociodemographic characteristics, clinical data of the patients that includes medical/drug history, laboratory values, number of drugs prescribed, patient diagnosis, comorbidities, and status of the patients (in/outpatient). Factors assumed to increase the risk of acquiring a DRP such as polypharmacy (defined as five or more drugs),[24] increased serum creatinine levels (≥1.5 mg/dl), diabetes mellitus, cardiac failure, history of allergy, adverse events to drugs, and use of narrow therapeutics index drugs that could affect to cause DRPs were all recorded to assess the outcomes.

All the data were collected by the six clinical pharmacists during their daily medication review process and were classified according to the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) classification for DRPs version 6.2 (Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe [homepage on the Internet]. The PCNE Classification for drug-related problems V 6.2. [updated January 14, 2010]. Available from: http://www.pcne.org/sig/drp/documents/PCNE%20classification%20V6-2.pdf. (Last accessed March, 2015]). To identify the DRPs resources such as Micromedex, Medscape, up-to-date and drugs.com were used and these were also used to aid the pharmacists in the provision of comprehensive pharmaceutical care in Cardiology Unit.

Assessment and classification of drug-related problems

DRPs were classified according to PCNE version 6.2 (Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe [homepage on the Internet]. The PCNE Classification for drug-related problems V 6.2. [updated January 14, 2010]. Available from: http://www.pcne.org/sig/drp/documents/PCNE%20classification%20V6-2.pdf. Accessed March, 2015).[17] The classification used was based on two domains 1. The problem identified (e.g., therapeutic effectiveness, adverse reactions, treatment costs, and others), and 2. The causes of DRPs (drug selection, drug form, dose selection, treatment duration, drug use/administration process, logistics, patient behavior, and others). Patient behavior such as forgot to use or take drug and stored drugs inappropriately.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 21.0 statistical package (IBM Corp., New York, USA). Descriptive data were presented in frequencies and percentage with mean and standard deviations. Bivariate analysis was performed and variables with P < 0.2 were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval was also computed for each variable for the corresponding P value. The value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 312 patients were followed in Cardiology Unit during the study. Of which, 64 (20.51%) were younger than 18 years, 19 (6.08%) patients were transferred to an emergency ward and 2 (0.64%) with an unclear diagnosis. After application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 227 (72.75%) adult patients were included in the study.

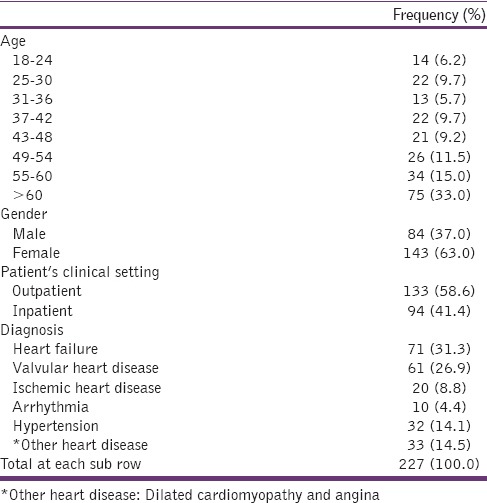

The mean age of the study patients was 52 ± 1.7 (range: 18–85) years, and the majority (63.0%) were female patients. Among patients who visited Cardiology Unit 133 (58.6%) were outpatients and 94 (41.4%) were inpatients. These were diagnosed with heart failure (71, 31.3%), valvular heart disease (61, 26.9%), hypertension (32, 14.1%), and other heart diseases, such as dilated cardiomyopathy and angina (33, 14.5%) [Table 1]. Ninety-eight (43.1%) patients were with more than five comorbidities, (mean value 5.8 ± 0.8). Polypharmacy was confirmed in 151 patients (57%) and was evident on 118 (44.5%) CVD patients with comorbidities. The mean number of medications was 4.9 ± 2.1 per patient, while the mean hospital stay was 4.9 ± 3.1 days per patient in cardiology ward.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (n=227 patients)

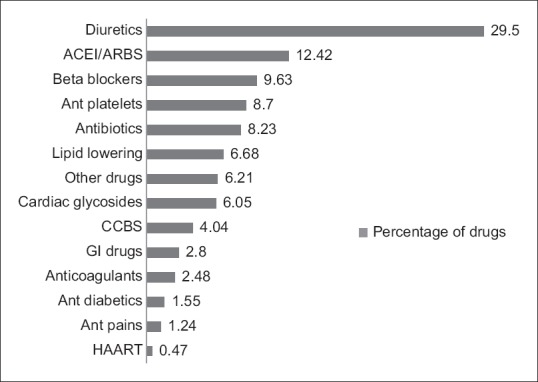

A total of 644 CV drugs were prescribed to the study population, with a mean of 3.5 ± 1.5 drugs per patient. The most commonly prescribed CV drug class included diuretics (190, 29.5%), followed by angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (80, 12.42%) and beta-blockers (62, 9.63%). The remaining classes of drugs are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The most commonly used drug classes (N=227 patients) ACEI: Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, ARBS: Angiotensin receptor blockers, CCBS: Calcium channel blockers, GI: Gastrointestinal, HAART: Highly active antiretroviral therapy

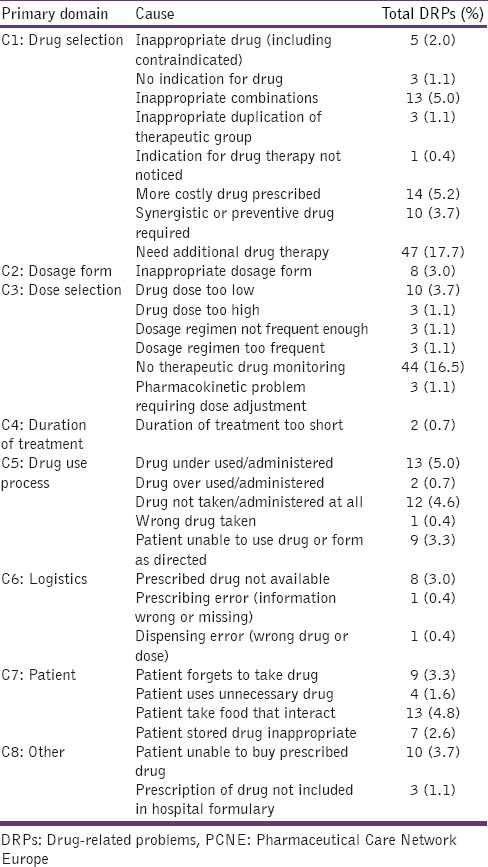

A total of 265 DRPs were detected in 227 patients with CVDs. At least one DRP was identified in 144 patients (63.4%), with a mean number 1.17 ± 1.1 DRP per patient. A higher number of at least one DRPs were identified in females (93, 35%), and inpatients (73, 27.5%), respectively. In all 265 DRPs detected, inappropriate drug selection (36.2%), inappropriate dose selection (24.9%), and inappropriate drug use process (14%) were the most identified DRPs [Table 2]. The distribution of DRPs identified by PCNE scale according to the cardiac diseases is shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Distribution of the type of DRPs detected according to PCNE scale (n=265 DRPs)

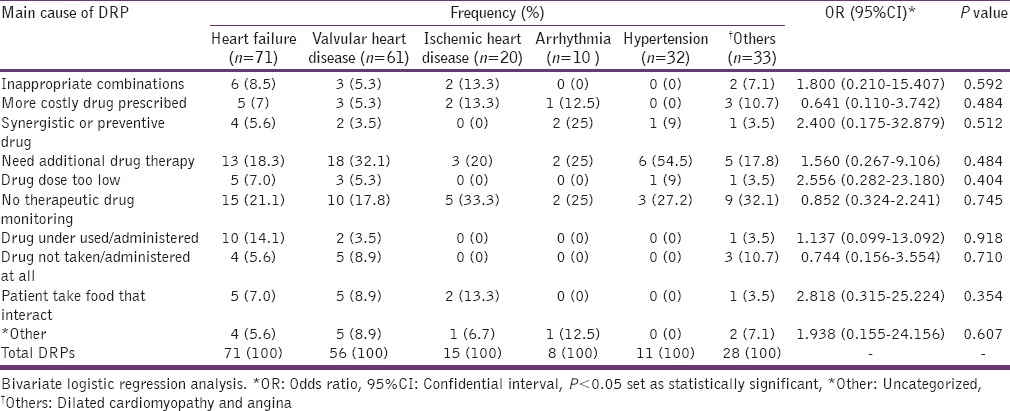

Table 3.

Distribution of the main causes of DRPs by type of heart disease

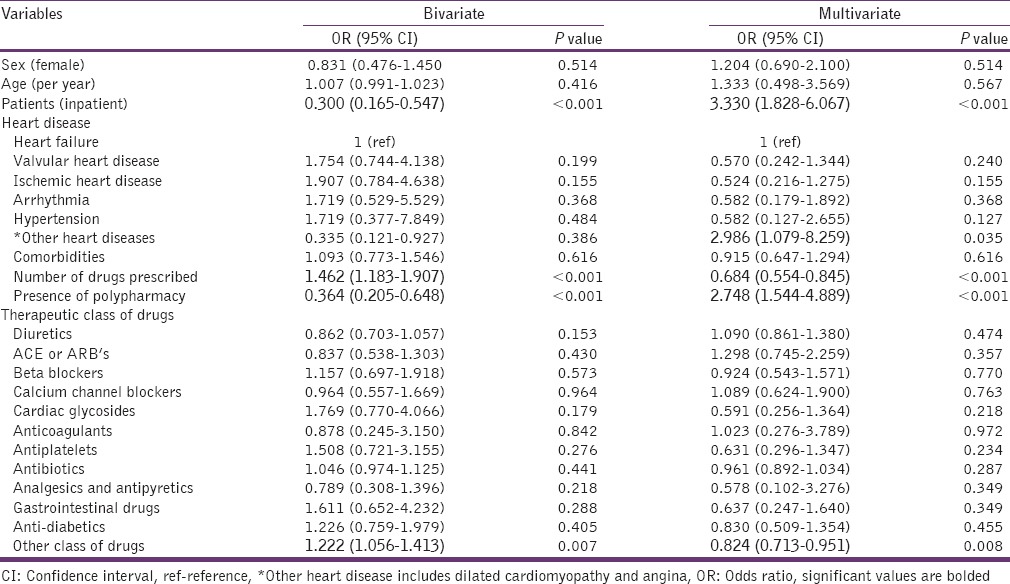

The bivariate and multivariate analysis of the CVD patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics compared with one or more DRPs are shown in Table 4. In the logistic regression analysis, some of the variables such as outpatients, patients with cardiomyopathy and angina, prescribing large number of drugs, the presence of polypharmacy and using other noncardiac related drugs influenced a greater extent to develop at least one DRP was similarly noticed in both bivariate and multivariate analysis [Table 4]. For example, a significant higher OR of 3.33 (P < 0.001) was predicted in inpatients in multivariate analysis than 0.30 (P < 0.001) in bivariate analysis. Similar results were also noticed with the presence of polypharmacy (0.36 in bivariate and 2.74 in multivariate analysis). However, a significant association was noticed with increase in number of drugs for the cardiac patients in both analysis, but the OR failed to predict the use of more drugs was reduced from 1.46 in the bivariate to 0.68 in the multivariate analysis. There was no significant difference noticed between gender, age, different cardiac diseases, and different cardiovascular drugs (P > 0.05) for developing at least one DRP.

Table 4.

Bivariate and multivariate model of patient's demographic and clinical characteristics with at least one drug related problem versus with no drug-related problem

Discussion

DRPs in patients with CVDs have been linked to increased risk of detrimental patient health outcome. However, it is challenging to investigate the risk factors that posesan increased risk of developing adverse events. This study was aimed to determine the risk factors associated for developing at least one DRP in patients with CVDs. We have tested the PCNE criteria in representative sample of patients with CVDs attending Cardiology Unit (in/outpatient) in GUH, Northwest Ethiopia.

The main findings of the study were the identification of DRPs and associated risk factors that are contributing to develop at least one DRP per patient with CVDs. We have identified certain groups at high risk for developing DRPs, such as older patients (≥60 years), hospitalized patients, polypharmacy, and presence of comorbidities. We found that 63.4% of patients with CVDs have at least one DRP, which was much higher than that reported by Urbina et al. (29.8%)[19] and Shareef et al. (55.3%) studies[25] respectively. However, the number of drugs prescribed per patient (3.5 ± 1.5) were associated with a higher risk of developing at least one DRP, which was similar to study conducted in North-Eastern part of Ethiopia, where the mean number of drugs prescribed were 3 ± 1.4 per patient[26] and lesser than the studies conducted in Spain (9.25 ± 4.9)[19] and Jordan (13.1).[27] These differences in our study may be due to several factors such as the cost of drugs, limited access to medications and socioeconomic factors.

In this study, nearly 30% of CVD patients taking five or more medications (polypharmacy) had at least one DRP. Although, other studies not specifically related to CVDs, have also found a significant correlation between polypharmacy and the risk of adverse drug reactions in especially the elderly population[28] and DRPs in hospitalized patients.[29] We have documented that for every drug added, there is a 17.7% increase in the risk of developing at least on DRPs. This suggests that there was a strong relationship between increasing number of drugs and an increasing number of DRPs. Hence, polypharmacy stands out as a marked risk determinant for heightening the DRPs.

In this study, patients with heart failure and valvular heart disease were associated with higher risk of developing at least one DRP, but no statistical significance association was noticed. However Urbina et al. study conducted on Spanish patients with CVDs has shown a significant association for developing at least one DRP in patients with heart failure and ischemic heart disease.[19] Further, 35.6% of outpatient's in our study had at least one DRP. This percentage is much lower than a study conducted in Geneva, where 69% of the outpatients with CVDs had at least one DRP.[22] Similarly in another study, 78% of the patients with heart failure managed at outpatients clinic had a DRP.[16] This variation was due to a lesser number of drugs used in Ethiopian outpatient settings.

In this study, inappropriate drug formulation, dosage selection, drug administration process, and patient-specific behavioral factors were some of the significant (P < 0.05) causes observed for the occurrence of DRPs. In contrast, Tegegne et al. study conducted in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, North-East Ethiopia identified more than 95% (96.1%) were due to inappropriate drug indications.[26] Whereas in Jordan, drug dosage and drug administration were found to be the major type of drugs and therapeutic problems in hospitalized patients.[27] These variations may be due to the lack of national policies, comprehensive management strategies to manage chronic diseases in Ethiopia and depending on self-judgments of practitioners while prescribing medications.

Need of additional drug therapy and therapeutic monitoring was significantly recognized DRPs in our patients, more than half of whom were outpatients. However, similar type of concerns was also seen in our hospitalized patients (P < 0.05). A cross-sectional observational study conducted in internal medicine ward also prioritized need of additional drug therapy as a major DRP in GUH.[30] Taking into account that our patients were specifically with CVDs and presumably had more comorbidities, our corresponding figures of, respectively, 20.7% and 19.3% were largely in line with the results of that study conducted in the same hospital. Compared to previous studies the number of DRPs identified in this study were much less since drugs for smoking cessation and alcoholism were not grouped as DRP unlike in other studies.[27,30] Furthermore, older age, having more than one comorbid condition and taking an average of four or more drugs per day were an independent predictor for developing DRPs. This finding was also previously reported in previous studies.[24,31] In 2011, a hospital-based study conducted in Southwest Ethiopia identified older age, female sex, polypharmacy, and potential drug-drug interactions were independent risk factors and predicted the occurrence of DRPs.[32] In addition, a cohort study in Bahirdar, North-East Ethiopia has shown patients with CVDs and associated co-morbidities were a predictor for the occurrence of DRPs.[26]

In this study, hospitalized patients with CVD (OR = 3.330; 95% CI = 1.828–6.067) were about 3 times more likely to develop DRP than outpatients. Patients with polypharmacy (2.748; 1.544–4.889) were also associated with increased risk of DRP. However, these results were also noted in other studies conducted on hospitalized patients.[33,34,35,36,37] Nevertheless, a prior study identified administration of a certain group of drugs during hospitalization (OR = 1.23; 95% CI = 1.15–1.31) as independent risk factor for developing DRP in cardiovascular patients.[19] Although no significant association between the risk of DRP and administration of CV drugs was noticed in our study, previous studies identified diuretics (OR = 1.7; 95% CI = 1.0–2.6) and psychoactive drugs may pose a risk for developing DRPs.[38]

In this study, the mean length of hospital stay for inpatients was found to be almost 5 days longer in patients with at least one DRP than others. These findings were much less than Urbina et al. study (9.58 days).[19] This suggests that increasing the number of DRPs can impact the prolonged hospital stay and increases the economic burden.[39] A possible solution for this findings is the integration of clinical pharmacists in the Cardiology Unit which might be helpful to provide exhaustive medication review for early detection and prevention of DRPs. Topics related to the economic impact of prolonged hospital stays need to be further examined.

Study limitations

Certain limitations must be considered when interpreting our findings. This study was conducted in one teaching hospital, and the results are not necessary representative of other hospitals in the country. The study was conducted for a short period which may not provide sufficient evidence for the long-term outcomes. Furthermore, some of the outpatients included in our study were naive patients; therefore, results may not be generalized to patients on long-term chronic CVDs. This study highlighted only the cardiovascular drugs used by the patients during the study period, and other active medications DRPs were not included in the study. Although this is a prospective cross-sectional study, it was not interventional. We did not assess pharmacist interventions and its acceptance by physicians; and the impact of DRP on patient outcomes.

Conclusion

The study identified 265 DRPs in 227 patients with CVDs with a mean of 1.17 ± 1.1 DRP per patient attending Cardiology Unit in GUH. The risk factors for developing DRPs in CVD patients were the need of additional drug therapy and lack of therapeutic monitoring. Comprehensive medication review by clinical pharmacists can aid early identification and prevent the DRPs in patients with CVDs in GUH.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, Davis A, Liang X, Zhou M. GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385:117–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Regional Committee for Africa. Cardiovascular Diseases in the African Region: Current Situation and Perspectives-report of the Regional Director. 2005. [Last accessed on 2015 Nov 08]. Available from: http://www.afro.who.int/rc55/documents/afr_rc55_12_cardiovascular.pdf .

- 3.Mensah GA, Roth GA, Sampson UK, Moran AE, Feigin VL, Forouzanfar MH, et al. Mortality from cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990-2013: A systematic analysis of data from the global burden of disease study 2013. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2015;26(2 Suppl 1):S6–10. doi: 10.5830/CVJA-2015-036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jamison DT, editor. Disease and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa-World Bank Publications. 2006. [Last accessed 2016 Apr 06]. Available from: https://books.google.com.et/books/Diseases+and+Mortality+in+Sub-Saharan+Africa+2nd+ed,+Ch+21+Washington,+DC:+World+Bank.html .

- 5.Moran A, Forouzanfar M, Sampson U, Chugh S, Feigin V, Mensah G. The epidemiology of cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: The global burden of diseases, injuries and risk factors 2010 Study. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;56:234–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misganaw A, Mariam DH, Ali A, Araya T. Epidemiology of major non-communicable diseases in Ethiopia: A systematic review. J Health Popul Nutr. 2014;32:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Misganaw A, Mariam DH, Araya T. The double mortality burden among adults in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2006-2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E84. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mocumbi AO. Lack of focus on cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2012;2:74–7. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2012.01.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fulton MM, Allen ER. Polypharmacy in the elderly: A literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17:123–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1041-2972.2005.0020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brager R, Sloand E. The spectrum of polypharmacy. Nurse Pract. 2005;30:44–50. doi: 10.1097/00006205-200506000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Amin M, Zindchenko A, Rana M, Uddain MN, Pervin S. Study on polypharmacy in patients with cardiovascular diseases. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2012;2:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appleton SC, Abel GA, Payne RA. Cardiovascular polypharmacy is not associated with unplanned hospitalization: Evidence from a retrospective cohort study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:58. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-15-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von Lueder TG, Atar D. Comorbidities and polypharmacy. Heart Fail Clin. 2014;10:367–72. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, Potter K, Le Couteur D, Rigby D, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: The process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:827–34. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Onder G, van der Cammen TJ, Petrovic M, Somers A, Rajkumar C. Strategies to reduce the risk of iatrogenic illness in complex older adults. Age Ageing. 2013;42:284–91. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe. The PCNE Classification for Drug-related Problems V 6.2. [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 01; Last updated on 2010 Jan 14]. Available from: http://www.pcne.org/sig/drp/documents/PCNE%20classification%20V6-2.pdf .

- 18.Viktil KK, Blix HS. The impact of clinical pharmacists on drug-related problems and clinical outcomes. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;102:275–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2007.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urbina O, Ferrández O, Luque S, Grau S, Mojal S, Pellicer R, et al. Patient risk factors for developing a drug-related problem in a cardiology ward. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;11:9–15. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S71749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gastelurrutia P, Benrimoj SI, Espejo J, Tuneu L, Mangues MA, Bayes-Genis A. Negative clinical outcomes associated with drug-related problems in heart failure (HF) outpatients: Impact of a pharmacist in a multidisciplinary HF clinic. J Card Fail. 2011;17:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nascimento Y, Carvalho WS, Acurcio FA. Drug-related problems observed in a pharmaceutical care service, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2009;45:321–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niquille A, Bugnon O. Relationship between drug-related problems and health outcomes: A cross-sectional study among cardiovascular patients. Pharm World Sci. 2010;32:512–9. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9401-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gondar University Referral Hospital Statistics and Information Center Unpublished Resource. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jyrkkä J, Enlund H, Korhonen MJ, Sulkava R, Hartikainen S. Patterns of drug use and factors associated with polypharmacy and excessive polypharmacy in elderly persons: Results of the Kuopio 75+study: A cross-sectional analysis. Drugs Aging. 2009;26:493–503. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200926060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shareef J, Sandeep B, Shastry CS. Assessment of drug related problems in patients with cardiovascular diseases in a tertiary care teaching hospital. J Pharm Care. 2014;2:70–6. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tegegne GT, Yimam B, Yesuf EA, Gelaw BK, Defersha AD. Drug therapy problems among patients with cardiovascular diseases in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, North East, Ethiopia. Int J Pharm Teach Pract. 2014;5:989–96. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aburuz SM, Bulatova NR, Yousef AM, Al-Ghazawi MA, Alawwa IA, Al-Saleh A. Comprehensive assessment of treatment related problems in hospitalized medicine patients in Jordan. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33:501–11. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9497-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onder G, Petrovic M, Tangiisuran B, Meinardi MC, Markito-Notenboom WP, Somers A, et al. Development and validation of a score to assess risk of adverse drug reactions among in-hospital patients 65 years or older: The GerontoNet ADR risk score. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1142–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blix HS, Viktil KK, Reikvam A, Moger TA, Hjemaas BJ, Pretsch P, et al. The majority of hospitalised patients have drug-related problems: Results from a prospective study in general hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;60:651–8. doi: 10.1007/s00228-004-0830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mekonnen AB, Yesuf EA, Odegard PS, Wega SS. Implementing ward based clinical pharmacy services in an Ethiopian University Hospital. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2013;11:51–7. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552013000100009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmad A, Mast MR, Nijpels G, Elders PJ, Dekker JM, Hugtenburg JG. Identification of drug-related problems of elderly patients discharged from hospital. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:155–65. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S48357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tigabu BM, Daba D, Habte B. Drug-related problems among medical ward patients in Jimma university specialized hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. J Res Pharm Pract. 2014;3:1–5. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.132702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shamliyan T. Adverse drug effects in hospitalized elderly: Data from the healthcare cost and utilization project. Clin Pharmacol. 2010;2:41–63. doi: 10.2147/CPAA.S8779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ayalew MB, Megersa TN, Mengistu YT. Drug-related problems in medical wards of Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Ethiopia. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4:216–21. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.167048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yadesa TM, Gudina EK, Angamo MT. Antimicrobial use-related problems and predictors among hospitalized medical in-patients in Southwest Ethiopia: Prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martínez-Arroyo JL, Gómez-García A, Sauceda-Martínez D. Polypharmacy prevalence and potentially inappropriate drug prescription in the elderly hospitalized for cardiovascular disease. Gac Med Mex. 2014;150(Suppl 1):29–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharifi H, Hasanloei MA, Mahmoudi J. Polypharmacy-induced drug-drug interactions; threats to patient safety. Drug Res (Stuttg) 2014;64:633–7. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1363965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Repp KL, Hayes C, 3rd, Woods TM, Allen KB, Kennedy K, Borkon MA. Drug-related problems and hospital admissions in cardiac transplant recipients. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1299–307. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skrepnek GH, Abarca J, Malone DC, Armstrong EP, Shirazi FM, Woosley RL. Incremental effects of concurrent pharmacotherapeutic regimens for heart failure on hospitalizations and costs. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:1785–91. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]