Abstract

Background:

Acute gastroenteritis and respiratory illnesses are the major causes of morbidity and mortality in children under 5 years of age. The objective of this study was to evaluate the prescription pattern of antibiotic utilization during the treatment of cough/cold and/or diarrhea in pediatric patients.

Methods:

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted for 6 months in pediatric units of a tertiary care hospital in South India. Children under 5 years of age presenting with illness related to diarrhea and/or cough/cold were included in this study. Data were collected by reviewing patient files and then assessed for its appropriateness against the criteria developed in view of the Medication Appropriateness Index and Guidelines of the Indian Academy of Pediatrics. The results were expressed in frequencies and percentages. Chi-square test was used to analyze the data. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

A total of 303 patients were studied during the study period. The mean age of the patients was 3.5 ± 0.6 years. The majority of children were admitted mainly due to chief complaint of fever (63%) and cough and cold (56.4%). The appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions was higher in bloody and watery diarrhea (83.3% and 82.6%; P < 0.05). Cephalosporins (46.2%) and penicillins (39.9%) were the most commonly prescribed antibiotics, though the generic prescriptions of these drugs were the lowest (13.5% and 10%, respectively). The seniority of prescriber was significantly associated with the appropriateness of prescriptions (P < 0.05). Antibiotics prescription was higher in cold/cough and diarrhea (93.5%) in comparison to cough/cold (85%) or diarrhea (75%) alone.

Conclusions:

The study observed high rates of antibiotic utilization in Chidambaram during the treatment of cough/cold and/or diarrhea in pediatric patients. The findings highlight the need for combined interventions using education and expert counseling, targeted to the clinical conditions and classes of antibiotic for which inappropriate usage is most common.

KEY WORDS: Appropriateness of antibiotics, children, cough/cold, diarrhea, drug utilization, prescription pattern

Irrational use of antibiotics is a global issue.[1,2] According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 50% medications are prescribed, dispensed, or sold inappropriately, and in that half of the patients took their medicines wrongly.[3] The irrational use of medications could be practiced in the form of overuse, underuse, and misuse of prescription or over-the-counter drugs.[1,2,3,4] It could also be due to the poor quality of antibiotic prescription, use of antibiotics in nonbacterial diseases, poor adherence and because of antibiotic resistance.[4]

Antibiotics are widely used to manage the clinical conditions prevalent in the pediatric population.[5] Researchers have estimated around 150 million prescriptions of antibiotics annually in the United States, and of those 30 million are prescribed in children.[6] Antibiotics are mostly prescribed for children as an empirical therapy. These drugs play a vital role in the management of any acute and chronic infectious diseases; however, if the use is not rational it could lead to severe consequences in the form of super-infections and multidrug resistance.[7] The methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli developed resistant to several different antibiotics. In India, the discovery of new enzyme the New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1 makes the bacteria resistant to all antibiotics including carbapenems.[8] Furthermore, due to antibiotic resistance patients are more likely to remain infectious for a longer time, increasing the risk of spreading resistant microorganisms to others. Therefore, it is essential to ensure the appropriateness of antibiotic prescriptions to promote the rational use of antibiotics.[9]

According to the WHO, pneumonia and diarrhea are among the leading causes of deaths in children under 5 years of age.[10] Diarrhea and respiratory illness are the major causes of morbidity and mortality in developing countries.[11] One in five deaths among children is due to diarrhea/respiratory illness, resulting in a loss of around 1.5 million lives annually.[11] Diarrhea is the third most common cause of death among children in India, killing an estimated 300,000 children in India each year.[12] Despite successful implementation of universal programs such as control of diarrheal disease and acute respiratory infection, the burden of diarrhea and cough/cold in India remains unacceptably high.

In India, many guidelines are available at national and state level for the management of cough/cold and/or diarrhea under the age of 5 years. National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM, 2011), National Formulary of India (2011), and Indian Academy of Pediatrics (IAP) have provided a comprehensive guideline to manage the above-mentioned problems.[13,14,15] These guidelines are in line with the national policy for the containment of antimicrobial resistance in India, prepared by the Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi.[16] The guidelines have recommended the use of oral rehydration solution and zinc supplements for the acute diarrheal condition, while antimicrobials (co-trimoxazole, metronidazole, ceftriaxone, and ciprofloxacin) are recommended for chronic diarrhea and dysentery. Similarly, for common cold and cough, no antibiotics are recommended while co-trimoxazole and amoxicillin are recommended for pneumonia and ampicillin and gentamycin for severe pneumonia.[3] Previous studies focused on the general use of antibiotics in the Paediatric Department,[17] while other study investigated the prescribing pattern of antibiotics in acute diarrhea among the general public.[18] Another study evaluated the prescribing pattern by doctors for acute diarrhea in children, but the study was limited to Northern India and was conducted in 1995.[19] None of these studies analyzed the prescriptions in view of the guidelines given by the Indian Academy of Paediatrics and Medication Appropriateness Index (MAI). Furthermore, there is no published study reporting the prescription of antibiotics in children in line with the NLEM. Moreover, there is a scarcity of relevant literature from Southern India. The objective of this study was to assess the prescribing pattern and appropriateness of antibiotics prescribed in the treatment of cough/cold and/or diarrhea in children below 5 years of age.

Methods

A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted for 6 months from December 2012 to May 2013. The study was carried out in inpatient pediatric units including one general ward and one Intensive Care Unit at Rajah Muthiah Medical College and Hospital (RMMCH), Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu. The hospital receives financial support from the state government; hence, treatment cost is very low which attracts patients from nearby rural areas and referral from government dispensaries and private clinics.

All children below 5 years of age admitted to inpatient department with symptoms of diarrhea, cough, and cold were recruited for this study. Cases were recognized as potential participants by daily review of patient profile and medication chart in participating wards. Data were collected on a predesigned form by a team of registered pharmacists on a daily basis. Content validity of the data collection form was performed by selecting a panel of four health-care professionals (two senior physicians and two pharmacy professors) who gave their opinion on the relativity of the content and its importance. Their suggestions were incorporated before finalizing the form for data collection. All the relevant data were collected by a thorough review of profiles, medication records, and other related notes. In the case of any difficulty in interpreting the information, on duty resident doctors were consulted to clarify the information. High confidentiality of data was maintained.

Information regarding the demographics (age, sex, weight, date of admission, and date of discharge) and clinical data (symptoms, chief complaints, past medication history and part medical history, time of the present episode of diarrhea, cough/cold, frequency of diarrhea, fever, vomiting, problem in breathing, cyanosis, any allergy, and family/social history) was identified and noted on the data collection form. Information regarding the dose, frequency, and route of administration of prescribed antibiotics was also noted from the patient medication chart by the data collectors.

The collected data were then analyzed for its appropriateness against the criteria developed in view of the MAI[1] and guidelines of the IAP.[15] Following aspects of the data were appraised in accordance with the developed criteria: An indication, effectiveness, posology, clinically significant drug-drug interactions, clinically significant drug-disease interactions, the practicality of the directions, the presence of least expensive alternative compared to others of equal utility, duplication with other drugs, and duration of therapy.[1] The collected data were also screened through the NLEM[13] to observe the prescription pattern in view of the NLEM. The prescribed medicines were also reviewed for their brand and generic prescriptions.

Data were then coded and entered into SPSS version 20 for Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) for statistical analysis. The results were expressed in frequencies and percentages. Chi-square test was also used to test the association between dependent (prescription appropriateness) and independent variables (designation of prescriber and disease conditions). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

This study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee of the RMMCH. A written consent was also obtained from the attendants of the patients. The permission to use prescriptions for research purpose was also granted from the medical superintendent and Head of the Department of Pediatrics of the studied hospital.

Results

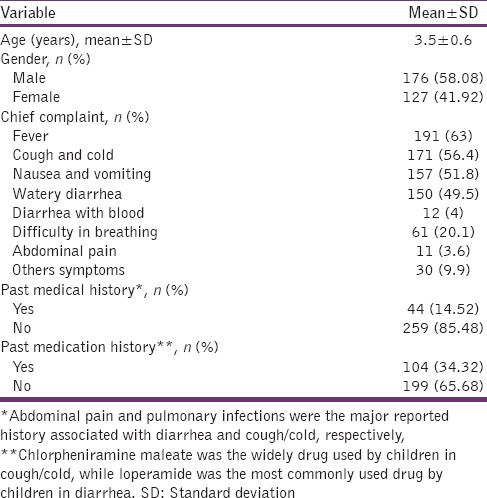

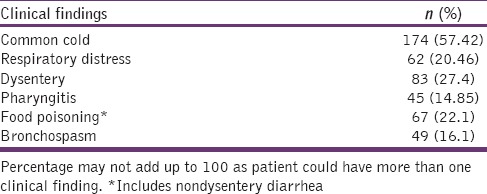

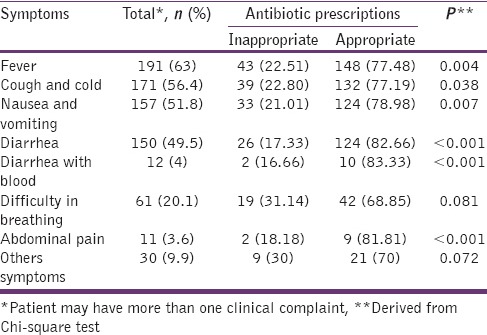

A total of 303 profiles were reviewed during the study period. The mean age of the patients was 3.5 ± 0.6 years. Children of male gender (n = 176, 58.08%) were higher in numbers as compared to female counterparts (n = 127, 41.92%). The majority of the children were admitted mainly due to chief complaint of fever (n = 191, 63%) followed by cough and cold (n = 171, 56.4%), nausea and vomiting (n = 157, 51.8%), and diarrhea (n = 150, 49.5%). On the contrary, abdominal pain was the least observed chief complaint of the studied children. Abdominal pain and pulmonary infections were the major reported history associated with diarrhea and cough/cold, respectively. Past medication history showed that 34.32% children were consuming medications before being admitted to the hospitals. Chlorpheniramine maleate was the main drug used by children with cough/cold, while loperamide was the most commonly used drug by children with diarrhea. The information is summarized in Table 1. The findings of this study revealed that common cold (57.42%) and dysentery (27.4%) were the major findings revealed upon clinical assessment. The complete description of clinical assessment is summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the participants

Table 2.

Clinical findings on assessment

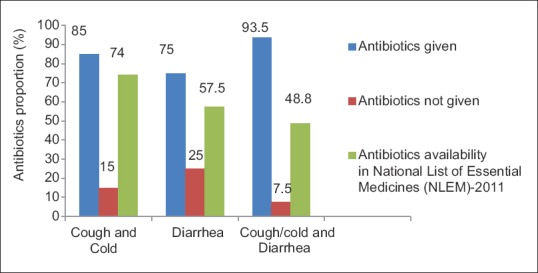

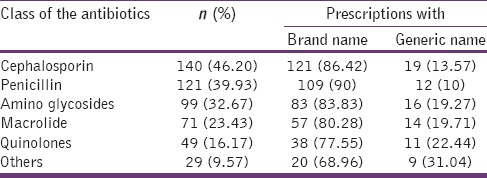

The study also evaluated the proportion of antibiotics given in different conditions, and it was found that 93.5% of drugs prescribed in a concomitant cold/cough and diarrhea were antibiotics. However, it was also noted that only 48.8% of these antibiotics were prescribed from the NLEM list. The percentage of prescribed antibiotics in cough/cold was 85% while in diarrhea the proportion of prescribed antibiotics was 75%. It was also noticed that 74% and 57.5% of antibiotics prescribed in these conditions were included in the NLEM list, respectively. This information is depicted in Figure 1. The data showed that cephalosporin was among the commonly prescribed drugs (46.2%, n = 140). Among cephalosporins, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefdinir, and cefixime were majorly prescribed. However, only 13.57% cephalosporins were prescribed by generic names. Furthermore, penicillins were second on the list with 39.93% prescriptions. However, with respect to generic prescribing, these drugs were lowest in prescriptions (10%). Aminoglycosides were prescribed in 32.67% patients in which gentamicin and amikacin were most extensively prescribed. In comparison, quinolones (ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin with or without the combination of metronidazole, and tinidazole) were the least prescribed drugs (16.17%) although their generic prescriptions were more than those of cephalosporins and penicillins (22.44%). This information is summarized in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Proportion of antibiotic prescribed in different conditions and their categorization in National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM)

Table 3.

Frequencies of antibiotic classes prescribed for cough and diarrhea

The findings of this study showed that prescriptions of antibiotic in bloody diarrhea (83.3%) and watery diarrhea (82.6%) were highly adherent toward the guideline (P < 0.001). Conversely, appropriateness was lowest for children with difficulty in breathing, though there was no significant association between this complaint and the rate of appropriateness (P > 0.05). In conditions such as fever, cough and cold, nausea, and vomiting, consistencies of data with the guidelines-based criteria were 77.4%, 77.1%, and 78.9%, respectively (P < 0.05). The complete description is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Inappropriateness of the antibiotics prescribed with cough/cold and diarrhea-related illnesses

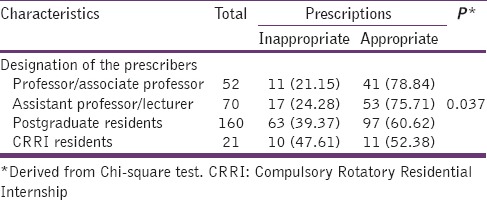

The findings also suggest that there was a significant difference in the appropriateness of the prescription of different designated prescribers (P < 0.05). The data show that highest level of consistency was observed in the antibiotic prescriptions of professor/associate professor (78.84%). Although postgraduate students were the major prescriber (n = 160/303), their appropriateness level (60.62%) was just above the Compulsory Rotatory Residential Internship residents (52.38%). The data are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Appropriateness of antibiotic according to designation of the prescriber

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge till date, this is the first study which has evaluated the prescription pattern and appropriateness of antibiotics among children with cough/cold and diarrhea in Southern India. Not much literature is known from the Southern region in India about the use of generic medicines and the use of medicines from the NLEM in children suffering from diarrhea and/or cough/cold. This study would add a significant contribution to the knowledge of the antibiotic use among children in Southern India and would serve as a reference the much-needed future studies.

The results suggest a high proportion of antibiotic use in children below 5 years of age in illnesses such as cough/cold and diarrhea. This finding is in accordance with other studies conducted in other developing countries.[9,20,21] The high percentage of antibiotic prescriptions may indicate a high probability of irrational use which may contribute toward resistance as discussed in previous studies.[22,23,24,25] The results were not following the WHO guidelines as high use of antibiotics was observed in conditions where the WHO does not recommend the use of antibiotics.[22] The likely reason for such findings could be the lack of awareness of antibiotics use among health-care professionals and also because of the lack of policy implementation in hospitals.[23]

A finding that is noteworthy to discuss is the frequent prescriptions of cephalosporins in this study. The potential consequences of such increased prescriptions could vary, but undoubtedly they will result in unwanted health expectations and potentially may give rise to ever important resistance issues.[26] This finding is also in line with another study where large numbers of similar antibiotics were prescribed among children suffering from diarrhea and/or cough/cold.[27] However, this result is not supported by another study conducted in Northern Tanzania that reported the highest use of penicillins in affected children.[3]

It has been established that the NLEM give a solution to many health-care problems and their availability and prescription promote rational use of medicines. However, in the current study, only 60% of antibiotics were prescribed from the NLEM. The results are not much different from other studies which assessed the relationship between a number of prescribed drugs and their availability.[28] The possible reasons for this could be the lack of prescriber information, unavailability of essential medicines in the hospital, and the lack of treatment guidelines. Generic prescriptions play an important in the determination of rational use of antibiotics. In the present study, 80% of antibiotics were prescribed by brand names. This result is not consistent with the study conducted by Panchal et al.[27] in 2013 where 50% of drugs were prescribed by generic names in children hospitalized with diarrhea in India.

A varied level of antibiotic appropriateness was observed in this study as the antibiotics prescribed for bloody diarrhea were more consistent with the guidelines in contrast to difficulty in breathing. The results were, however, opposite in the previous study where antibiotics prescribed in difficult breathing conditions were more appropriate in view of standard guidelines.[3] The likely reasons for this discrepancy could be speculated as diagnostic uncertainty, lack of awareness about treatment guidelines, and scarcity of medication use reviews in the studied hospital. This highlights the need of developing comprehensive policies regarding review of medications, establishing treatment guidelines, and educating prescribers about these guidelines periodically.[25]

Inappropriate prescribing was commonly observed by all the prescribers; however, a linear relationship was observed between the designation of the prescriber and the rate of appropriate prescription. Prescriptions of professors and associate professors were more consistent with the guidelines as compared to assistant professors and lecturers. The results are supported by other studies conducted elsewhere in India[28,29] and Northern Tanzania.[3] These studies reported that highly qualified prescribers and those with better opportunities of updating knowledge were more associated with rational prescribing. However, Kristiansson et al.[20] in 2008 reported no significant difference among prescribers with respect to appropriateness. This shows that continuous medical education should be promoted to promote rational use of antibiotics.

There are many strengths of this study with some limitations. This is the first study that evaluated the appropriateness of antibiotics both in cold/cough and diarrhea among the children aged <5 years in South Indian rural population. Furthermore, the prescribed antibiotics were also screened through the NLEM. In addition, the antibiotics were reviewed for the brand and generic prescriptions. The requirements for the physicians, in terms of qualification and experience, to work in teaching hospitals are same throughout the state hospitals; therefore, we speculate our results to be valid in the other state hospitals; however, more studies are required from other state hospitals to validate our findings. The results may not be generalizable to primary health centers and other private hospitals and clinics.

Conclusions

Overall, high proportions of antibiotics were prescribed in cough/cold and/or diarrhea in RMMCH, Chidambaram. The appropriateness of prescribed antibiotics with respect to standard guidelines varied with the clinical conditions. Cephalosporins were the most commonly prescribed drugs among children. The generic prescriptions of antibiotics were poor and a very low number of antibiotics were prescribed from the NLEM. Continuous education programs such as workshops or symposium, on disease management and antibiotic prescription in children, may promote rational use of antibiotics.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ahmad A, Parimalakrishnan S, Mohanta GP, Patel I, Manna PK. A study on utilization pattern of higher generation antibiotics among patients visiting community pharmacies in Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu at South India. Int J Pharm. 2012;2:466–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma S, Sethi GR, Gupta U. Standard Treatment Guidelines – A Manual for Medical Therapeutics. 3rd ed. New Delhi: Delhi Society for Promotion of Rational Use of Drugs, B I Publishing House Pvt. Ltd; 2009. pp. 116–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gwimile JJ, Shekalaghe SA, Kapanda GN, Kisanga ER. Antibiotic prescribing practice in management of cough and/or diarrhoea in Moshi Municipality, Northern Tanzania: Cross-sectional descriptive study. Pan Afr Med J. 2013;12:103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmad A, Parimalakrishnan S, Patel I, Praveen Kumar NV, Balkrishnan R, Mohanta GP. Evaluation of self-medication antibiotics use pattern among patients attending community pharmacies in rural India, Uttar Pradesh. J Pharm Res. 2012;5:765–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferris TG, Saglam D, Stafford RS, Causino N, Starfield B, Culpepper L, et al. Changes in the daily practice of primary care for children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:227–33. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group. WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet. 2005;365:1147–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ansam S, Ghada AB, Laila A, Waleed S, Rowa AR, Nidal J. Pattern of parenteral antimicrobial prescription among pediatric patients in Al-Watani Government Hospital in Palestina. An Najah Univ J Res. 2006;20:191–206. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmad A, Patel I. Schedule H1: Is it a solution to curve antimicrobial misuse in India? Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(Suppl 1):S55–6. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.121228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha V, Abid M, Mohanata GP, Patra A, Kishore K, Khan NA. Assessment of antimicrobials use in pediatrics in Moradabad city. Indian J Pharm Pract. 2010;3:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoan le T, Chuc NT, Ottosson E, Allebeck P. Drug use among children under 5 with respiratory illness and/or diarrhoea in a rural district of Vietnam. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18:448–53. doi: 10.1002/pds.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. The Treatment of Diarrhoea: A Manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. 4th Revision Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 10]. p. 4. Available from: http://www.whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2005/9241593180.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakshminarayanan S, Jayalakshmy R. Diarrheal diseases among children in India: Current scenario and future perspectives. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2015;6:24–8. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.149073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National List of Essential Medicines 2011, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 12]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in/WriteReadData/l892s/4767463099list.pdf .

- 14.National Formulary of India 2011, Indian Pharmacopoeia Commission, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare Government of India. [Last accessed on 2013 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/writereaddata/NFI_2011%20(1).pdf .

- 15.Bhatnagar S, Wadhwa N. Recent trends in the management of acute watery diarrhea in children. In: Bavdekar A, Matthai J, Sathiyasekaran M, Yachha SK, editors. IAP Specialty Series on Pediatric Gastroenterology. New Delhi: Jaypee Publishers; 2008. pp. 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Policy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance India. Directorate General of Health Services Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. New Delhi: 2011. [Last accessed on 2012 Nov 30]. Available from: http://www.nicd.nic.in/ab_policy.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanish R, Gupta K, Juneja S, Bains HS, Kaushal S. Prescribing pattern and pharmacoeconomics of antibiotic use in the department of pediatrics of a tertiary care medical college hospital in Northern India. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2015;8:101. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotwani A, Chaudhury RR, Holloway K. Antibiotic-prescribing practices of primary care prescribers for acute diarrhea in New Delhi, India. Value Health. 2012;15(1 Suppl):S116–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh J, Bora D, Sachdeva V, Sharma RS, Verghese T. Prescribing pattern by doctors for acute diarrhoea in children in Delhi, India. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1995;13:229–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kristiansson C, Reilly M, Gotuzzo E, Rodriguez H, Bartoloni A, Thorson A, et al. Antibiotic use and health-seeking behaviour in an underprivileged area of Perú. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:434–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui L, Li XS, Zeng XJ, Dai YH, Foy HM. Patterns and determinants of use of antibiotics for acute respiratory tract infection in children in China. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:560–4. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199706000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schindler C, Krappweis J, Morgenstern I, Kirch W. Prescriptions of systemic antibiotics for children in Germany aged between 0 and 6 years. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12:113–20. doi: 10.1002/pds.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children Guidelines for the Management of Common Illnesses with Limited Resources. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. pp. 72–81. 109-30. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sahoo KC, Tamhankar AJ, Johansson E, Lundborg CS. Antibiotic use, resistance development and environmental factors: A qualitative study among healthcare professionals in Orissa, India. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:629. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chukwuani CM, Onifade M, Sumonu K. Survey of drug use practices and antibiotic prescribing pattern at a general hospital in Nigeria. Pharm World Sci. 2002;24:188–95. doi: 10.1023/a:1020570930844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer E, Schwab F, Schroeren BB, Gastmeier P. Research dramatic increase of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli in German Intensive Care Units: Secular trends in antibiotic drug use and bacterial resistance, 2001 to 2008. Crit Care. 2010;14:R113. doi: 10.1186/cc9062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panchal JR, Desai CK, Iyer GS, Patel PP, Dikshit RK. Prescribing pattern and appropriateness of drug treatment of diarrhoea in hospitalised children at a tertiary care hospital in India. Int J Med Public Health. 2013;3:335. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah V, Mehta DS. Drug utilization pattern at medicine OPD at tertiary care hospital at Surendranagar. Int J Biomed Adv Res. 2014;5:80–2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar R, Indira K, Rizvi A, Rizvi T, Jeyaseelan L. Antibiotic prescribing practices in primary and secondary health care facilities in Uttar Pradesh, India. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2008;33:625–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]