Abstract

Literature on the association of methylphenidate and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) is sparse. This report discusses a case of a 14-year-old boy, who developed OCS (in the form of need for symmetry, obsessive doubts; compulsive symptoms included the need to order/arrange articles and repeated checking behavior), within 10 days of starting methylphenidate at the dose of 15 mg/day. Stoppage of methylphenidate led to amelioration of OCS over 2 weeks. The case description suggests that whenever a child on stimulants presents with new-onset OCS, association of OCS with stimulants must be suspected before considering an independent diagnosis of comorbid OCS/obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Key words: Compulsions, methylphenidate, obsessions, psychiatric disorder

Introduction

Stimulant medications such as methylphenidate have been used extensively for the management of attention deficit hyperkinetic disorder (ADHD). The efficacy and safety of methylphenidate have been examined in numerous clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.[1] Available evidence suggests that stimulants are more effective than placebo, with effect sizes varying from 0.8 to 1.1 and a positive early response in approximately 70% of cases.[1] The most common side effects associated with methylphenidate are insomnia, headache, irritability, agitation, loss of appetite, nausea, and weight loss.[1]

Obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) as a side effect of methylphenidate have rarely been reported. There are occasional case reports describing these in children and adolescents.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8] In this report, we present a case of an adolescent boy diagnosed with ADHD and mixed disorder of scholastic skills, who developed OCS after starting methylphenidate, which resolved completely after stoppage of the medication, and review the literature on the association of OCS with methylphenidate.

Case Report

A 14-year-old boy presented to the hospital with a history of behavioral problems since early childhood. Since 3 years of age, he was found to be fidgety, would frequently run about/leave his place in situations where he was expected to be seated, would not be able to engage in play activities calmly with friends, would not be able to wait for his turn, and would frequently interrupt others during their conversation. He would frequently forget his belongings in school and would easily get distracted with the slightest of noise. He would have difficulty in sustaining attention on tasks including studies, play activities, and would leave the same unfinished.

In addition, since 6 years of age, he had difficulty in reading, i.e., would read words incorrectly and slowly; had difficulties in written expression, i.e., would make multiple grammatical errors, write mirror images of alphabets, had lack of clarity in his writings, had difficulties with number sense, calculations, and problem-solving.

Over the years, his symptoms kept on worsening, and he continued to have poor grades in the school. He was diagnosed to have ADHD along with mixed disorder of scholastic skills (after detailed assessment for learning disability) at 14 years of age. In view of ADHD, he was started on methylphenidate and the dose was gradually increased to 15 mg/day.

Within 10 days of starting methylphenidate, he started to have OCS in the form of need for symmetry or exactness about furniture/paper/books being properly aligned, worry about words not being said in a “perfect” way, and obsessive doubts. Compulsive symptoms included the need to order/arrange articles, checking locks and appliances repeatedly, and the need to repeat routine activities such as turning appliances on and off, and going in and out of doorway unless he felt he did it the right number of times (not associated with magical thinking). During this period, there was no associated history of fever, sore throat, arthralgia, skin lesions, tics, depressive, manic, and psychotic symptoms. Past history and family history did not reveal any evidence of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

In view of the temporal correlation of onset of OCS with methylphenidate, an association of two was suspected and methylphenidate was stopped. Over the period of the next 2 weeks, the OCS subsided completely. In view of the disappearance of symptoms with stoppage of methylphenidate, a diagnosis of methylphenidate-associated OCS was made. Later, he was managed with nonpharmacological measures for his ADHD as family refused to administer any medication.

Discussion

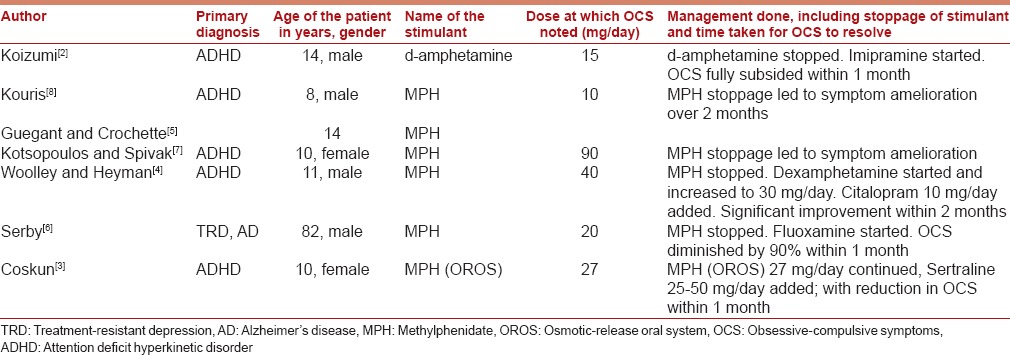

OCSs are rarely described in patients treated with psychostimulants. A search of PubMed revealed only seven case reports of patients who developed OCS with stimulant medications[2,3,4,5,6,7,8] and only one study reported on the prevalence of OCS with stimulants.[9] As is evident from Table 1, in eight out of the nine cases, stimulants were used for ADHD and in one case stimulant was used for the management of treatment-resistant depression in an 82-year-old man. All the children and adolescents were aged 8–14 years and there was slight preponderance for boys.[2,4,8] All cases of OCS were seen with the use of methylphenidate,[2,4,5,6,7,8] with the exception of one case description in which OCS was noted with the use of d-amphetamine.[2] The dose range of methylphenidate, at which OCSs were noted, varied from 10 to 90 mg/day, and in few cases, OCSs were accompanied by tics.[5,8] In the majority of cases, OCSs emerged during the initial phase of treatment with methylphenidate; however, in few cases, OCSs were detected after 10 months[5] to 2 years.[7] In majority of the cases, stoppage of methylphenidate led to amelioration of OCSs or significant improvement in OCSs in 1–2-month time. However, in few cases, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors were used for the management of OCS.[3,4,5] The type of OCSs varied across the case reports, with some authors reporting typical OCSs such as repeated hand washing,[3,4,8] wiping the furniture and walls with shirt sleeves,[2] checking rituals,[3] and reassurance seeking[3,4]. In other case reports, OCSs included compulsive stealing and hoarding,[7] thoughts of stabbing and killing people, thoughts of mother doing dirty things; compulsions in the form of drumming, crowing,[2] smelling people, food, and cloths, ordering and symmetry,[3] locking and unlocking and writing excessively about mechanics of locking and unlocking, and tying and untying shoelaces repeatedly.[6] There is the only one study that evaluated abnormal movements or perserverative/compulsive behaviors with the use of stimulants and reported that 34 (76%) out of 45 hyperactive boys had such symptoms. However, these adverse effects were transient and in only one case, severe OCS led to discontinuation of stimulant. The authors noted that compulsive behavior, resembling typical OCD, was more common with dextroamphetamine when compared with methylphenidate. Further, it was observed that compulsive behaviors associated with tics were seen only with methylphenidate.[9]

Table 1.

Case reports of obsessive-compulsive symptoms seen with stimulants

These reports suggest that though rare, OCSs can present as adverse effects of methylphenidate. Hence, whenever a child who is on stimulants presents with new-onset OCS, the association of OCS with stimulants must be suspected before considering an independent diagnosis of comorbid OCS/OCD. In such situations, stoppage of methylphenidate must be considered as a first step in the management of OCS; however, if the symptoms of OCS persist, then the addition of anti-obsessional agents such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be considered.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Storebø OJ, Krogh HB, Ramstad E, Moreira-Maia CR, Holmskov M, Skoog M, et al. Methylphenidate for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Cochrane systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 2015;351:h5203. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h5203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koizumi HM. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms following stimulants. Biol Psychiatry. 1985;20:1332–3. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coskun M. Methylphenidate induced obsessive-compulsive symptoms treated with sertraline. Bull Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;21:274. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolley JB, Heyman I. Dexamphetamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:183. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guegant G, Crochette A. Methylphenidate, tics and compulsions. Encephale. 2000;26:45–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serby M. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsive symptoms in an elderly man. CNS Spectr. 2003;8:612–3. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900018885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotsopoulos S, Spivak M. Obsessive-compulsive symptoms secondary to methylphenidate treatment. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46:89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouris S. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:135. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199802000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borcherding BG, Keysor CS, Rapoport JL, Elia J, Amass J. Motor/vocal tics and compulsive behaviors on stimulant drugs: Is there a common vulnerability? Psychiatry Res. 1990;33:83–94. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(90)90151-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]