Abstract

With only 33 cases reported so far, a purely extra-axial position of medulloblastoma at cerebellopontine (CP) angle is quite exceptional. We report a case of extra-axial medulloblastoma in a 15-year-old male child located in the CP angle that was surgically treated with a provisional diagnosis of schwannoma. Histopathological diagnosis of medulloblastoma was made with the routine hematoxylin and eosin stain and immunohistochemical markers. This case report highlights the fact that although extremely rare, the possibility of an extra-axial mass being a medulloblastoma does exist.

Key words: Cerebellopontine angle, extra-axial, medulloblastoma, pediatric neoplasms

Introduction

Medulloblastoma is a malignant, invasive embryonal tumor of the cerebellum with preferential manifestation in children, accounting for 16% of all pediatric brain tumors and 40% of childhood cerebellar tumors.[1] About 75% of pediatric medulloblastomas arise in the vermis and the fourth ventricle.[2] However, a purely extra-axial position at the cerebellopontine (CP) angle as reported in this paper is quite exceptional and nearly 33 cases have been reported in literature so far.[3] We report a case of extra-axial medulloblastoma in a 15-year-old male child located in the CP angle that was surgically treated. This case report highlights the fact that although extremely rare, the possibility of an extra-axial mass being a medulloblastoma does exist.

Case Report

A 15-year-old male presented with a short history of brief spells of sharp-shooting headaches for the last 3 months, bouts of nausea and vomiting for 2 months, followed by disturbed gait for the last 1 month. On examination, ataxia was noted. There was no other neurologic deficit. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a well-defined extra-axial mass in the left CP angle cistern with a broad dural base causing mass effect on underlying cerebellum and brainstem, with resultant compression and displacement of the fourth ventricle causing upstream obstructive hydrocephalus. Mass showed heterogeneous signal intensity with areas of necrosis/cystic degeneration. Mild perifocal edema was also present [Figure 1a]. The mass showing moderate heterogeneous contrast enhancement with small, nonenhancing areas within along with mass effect was noted on the pons and middle cerebellar peduncle with tonsillar herniation [Figure 1b]. Diffusion-weighted images showed restricted diffusion suggesting dense cellularity [Figure 1c]. Based on the radiological findings, differential diagnoses of schwannoma and meningioma were considered. The patient underwent a retromastoid suboccipital craniectomy exposing an extra-axial mass adherent to the petrous part of the dura, which was grayish-white, soft, suckable, and minimally vascular. Gross total excision was done. The peroperative specimen sent to the histopathology laboratory was subjected to squash smear preparation. Hematoxylin and eosin- and toluidine blue-stained squash smears showed scattered, round cells appearing to be lymphocytes [Figure 2]. Based on the above findings, an infective etiology was suggested on the peroperative squash smears. The latter specimen received in formalin for paraffin sections showed a cellular tumor exhibiting pale nodular areas surrounded by densely packed hyperchromatic cells [Figure 3a], with round to oval or carrot-shaped hyperchromatic nuclei surrounded by scanty cytoplasm, occasional neuroblastic rosettes, and brisk mitosis [Figure 3b]. Reticulin stain showed the reticulin-free pale islands surrounded by dense intercellular reticulin fiber network; immunohistochemistry showed strongly immunopositive tumor cells for synaptophysin and neuron-specific enolase [Figure 3c]. Tumor overall showed a high proliferative activity as high labeling index determined by Ki-67 antibody. This case was reported as desmoplastic/nodular (D/N) medulloblastoma (WHO Grade IV). Large, pale nodular areas in the paraffin sections explain the squash smear being reported as infective lesion as probably this was the area which was picked up in the squash smears. This also highlights the importance and role of adequate sampling during peroperative squash smears and frozen sections preparation.

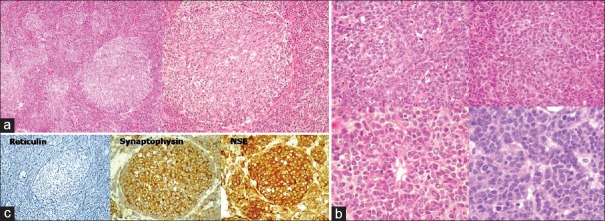

Figure 1.

(a) Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery and coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging images showing a well-defined extra-axial mass in the left cerebellopontine angle cistern with a broad dural base causing mass effect on underlying cerebellum and brainstem with resultant compression and displacement of the fourth ventricle causing upstream obstructive hydrocephalus. Heterogeneous signal intensity with areas of necrosis/cystic degeneration and mild perifocal edema is also seen. (b) T1-weighted coronal and sagittal magnetic resonance imaging images with contrast showing moderate heterogeneous enhancement with small, nonenhancing areas within along with mass effect on the pons and middle cerebellar peduncle with tonsillar herniation. (c) Diffusion-weighted images showing restricted diffusion

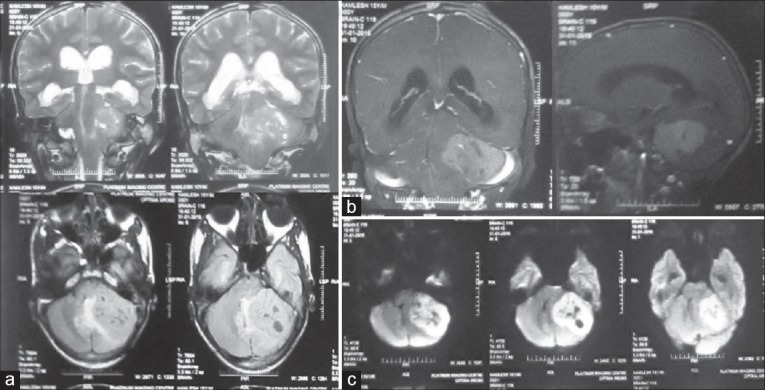

Figure 2.

Squash smears showing scattered round cells (H and E and TB, ×400)

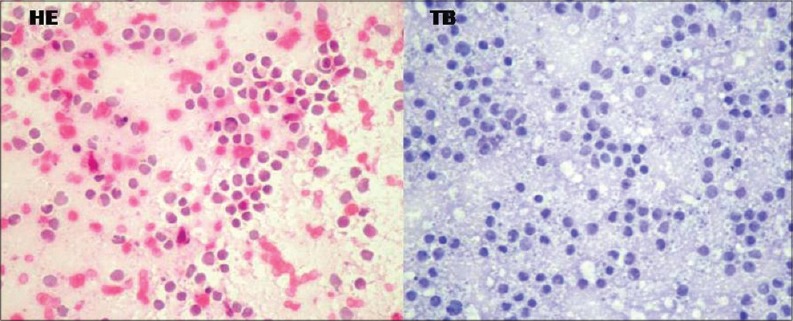

Figure 3.

(a) Histopathology showing a cellular tumor exhibiting pale nodular areas surrounded by densely packed hyperchromatic cells (HE, ×100; ×200). (b) Histopathology showing densely packed cells with round to oval or carrot-shaped hyperchromatic nuclei surrounded by scanty cytoplasm, occasional neuroblastic rosettes, and brisk mitosis (HE, ×400). (c) Reticulin stain showing reticulin free pale islands surrounded by dense intercellular reticulin fiber network (×200); tumor cells showing strong immunopositivity for synaptophysin and neuron-specific enolase (×400)

The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was advised to undergo radiotherapy and follow-up. However, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

About 80% of medulloblastomas arise in the cerebellar midline at inferior vermis and typically project into and fill the fourth ventricle. A smaller proportion of medulloblastomas are located in the cerebellar hemispheres, usually manifesting in adolescents or young adults. Medulloblastomas manifesting at extra-axial location other than these usual locations are extremely rare.[3] Common CP angle tumors usually include schwannomas, meningiomas, primary cholesteatomas, and epidermoid tumors; collectively these neoplasms account for up to 98% of CP angle neoplasms.[4] It has been suggested that extra-axial medulloblastomas located at CP angle may originate either by the proliferating remnants of the external granular layers of the cerebellar hemispheres including the flocculus[5] or from germinal cells or their remnants present at posterior medullary velum.[6] Akay et al. suggested that extra-axial medulloblastomas at CP angle arise by the lateral extension from the fourth ventricle through the foramen of Luschka, or there may be direct exophytic growth from the site of origin at the surface of cerebellum or pons.[7]

Clinically, trigeminal, abducens, and vestibulocochlear nerves are most commonly affected with associated cerebellar dysfunctions. However, there are no specific clinical or radiological findings peculiar to CP angle medulloblastomas. Some associated clinical features, however, differentiate medulloblastoma from a CP angle schwannoma, which is the more common entity at this location. The early onset of progressive cerebellar and gait symptoms suggest the possibility of a medulloblastoma, while positional nystagmus suggests the possibility of a schwannoma.[8] As far as radiological findings are concerned, it has been reported by Britton that the presence of normal internal auditory canal suggests the possibility of a medulloblastoma, thus differentiating it from schwannoma at CP angle.[9] However, this has also been reported in other CP angle neuroepithelial tumors. Though modern neuroradiological tools have made the diagnosis of intracranial lesions easier, and allow careful surgical planning. However, the presentation of medulloblastoma as an extra-axial mass still poses a preoperative diagnostic challenge. Computed tomography shows a well-defined mass at CP angle with heterogeneous contrast enhancement while MRI shows a well-defined mass that is isointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. With gadolinium contrast, it shows homogeneous enhancement.

Macroscopically, these are circumscribed, pink or gray neoplasms which may contain areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or calcification though medulloblastomas in the lateral cerebellar cortex and CP angle tend to be firm because they have predominant areas showing desmoplasia. Histopathology shows sheets of isomorphic cells with a high nucleocytoplasmic ratio with scattered mitotic figures and apoptotic bodies. Necrosis is variably present. Four variants of medulloblastoma listed in the WHO Classification 2007 are D/N medulloblastoma, medulloblastoma with extensive nodularity, anaplastic medulloblastoma (A), and large cell medulloblastoma (LC). Significant advances have been made in the molecular characterization and treatment of childhood medulloblastoma; based on the gene expression profiling classic medulloblastoma along with the variants, they are divided into four molecular subgroups which include WNT (classic >> LC/A), SHH (desmoplastic; classic = LC/A), Gp3 (classic, LC/A), and Gp4 (classic > LC/A). Except for the SHH subgroup, all other molecular subgroups manifest in childhood and the SHH subgroup manifests in infancy or adulthood. WNT subgroup has a very good prognosis, SHH subgroup shows a varied prognosis with better results in the desmoplastic variant, Gp3 subgroup has a poor prognosis, while Gp4 subgroup shows an intermediate prognosis.

CP angle medulloblastomas are basically a surgically treated disease. Concerning the management, the best therapeutic approach for these neoplasms is surgery along with radiotherapy. The 30% 5-year survival in the 1960s has now risen to 60%–70%, attributed to improved surgical techniques and more refined adjuvant therapies which combine radiotherapeutic and chemotherapeutic regimens.[10]

Conclusion

An extra-axial medulloblastoma is an extremely rare entity. Although simple to diagnose on histopathology, medulloblastomas at unusual sites can pose a preoperative radiologic dilemma even with the current technology available as the radiologic findings overlap with more common extra-axial masses such as schwannomas or meningiomas. The current challenges include finding novel therapies for aggressive disease and the accurate identification of disease risk to facilitate the targeted use of adjuvant therapies, intensive regimens for high-risk tumors, and reduced long-term adverse effects for patients with relatively responsive tumors.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Beygi S, Saadat S, Jazayeri SB, Rahimi-Movaghar V. Epidemiology of pediatric primary malignant central nervous system tumors in Iran: A 10 year report of national cancer registry. Cancer Epidemiol. 2013;37:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yazigi-Rivard L, Masserot C, Lachenaud J, Diebold-Pressac I, Aprahamian A, Avran D, et al. Childhood medulloblastoma. Arch Pediatr. 2008;15:1794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2008.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar R, Bhowmick U, Kalra SK, Mahapatra AK. Pediatric cerebellopontine angle medulloblastomas. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2008;3:127–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barkovich AJ. Pediatric Neuroimaging. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaiswal AK, Mahapatra AK, Sharma MC. Cerebellopointine angle medulloblastoma. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:42–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2003.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raaf J, Kernohan JW. Relation of abnormal collection of cells in posterior medullary velum of cerebellum to origin of medulloblastoma. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1944;52:163–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akay KM, Erdogan E, Izci Y, Kaya A, Timurkaynak E. Medulloblastoma of the cerebellopontine angle – Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2003;43:555–8. doi: 10.2176/nmc.43.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.House JL, Burt MR. Primary CNS tumors presenting as cerebellopontine angle tumors. Am J Otol. 1985 Nov;(Suppl 6):147–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Britton BH. Adult medulloblastoma: Neurotologic manifestations. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1975;84(3):364–7. doi: 10.1177/000348947508400313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutka JT, Kuo JS, Carter M, Ray A, Ueda S, Mainprize TG. Advances in the treatment of pediatric brain tumors. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004;4:879–93. doi: 10.1586/14737175.4.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]