Abstract

Association of Dandy–Walker syndrome with occipital meningocele (OMC) is extremely rare and about thirty cases are reported till date in the Western literature. However, OMC is classified by Talamonti et al. into small, large, and giant categories with respective diameters were upto 5 cm in small, large with 5–9 cm, and giant with >9 cm. Usually the size of OMC progressively increases as raised intracranial pressure leads to compensatory cerebrospinal fluid escape into sac with the growth of children. Authors report an interesting case of an 18-month-old female child with extra-gigantic OMC, whose size was almost same since birth, representing the first case of its kind, who underwent successful surgical repair. Clinical presentation, radiological features, and surgical management options in literature are reviewed briefly for this rare disease association.

Key words: Cranial dysraphism, Dandy–Walker syndrome, meningocele, occipital meningocele

Introduction

Dandy–Walker syndrome (DWS) is a rare developmental malformation of the brain. Congenital malformations including agenesis of corpus callosum, heterotopias, gyral abnormalities, syringomyelia, and cardiac defects may be commonly associated with DWS, however association with gigantic occipital meningocele (OMC) is extremely rare.[1,2] In 2011, Talamonti et al. classified OMC depending on the size of meningocele sac into three subgroups: Small, large, and giant with respective diameters were up to 5 cm in small, large with 5–9 cm, and giant over >9 cm.[3] Talamonti et al. could collect a total of thirty cases, including their own single case and observed that all cases seek medical advice soon after birth, six had large OMC, and further only three cases had giant variety of OMC in their review.[3] In 2016, Singh et al. reported another one case of DWS with giant OMC associated with craniovertebral anomalies.[4] A total of 31 cases of DWS with OMC are reported in literature till date; however, the current case which represented extra-gigantic size of sac could seek medical advice after 1½ years after birth due to poor socioeconomic condition with almost size of the sac remained static since birth itself, underwent successful surgical repair, and 800 ml of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was evacuated during surgery from the sac of OMC, representing the first case of its kind in the Western literature. The etiopathogenesis of DWS is poorly understood.[2,3,4] Authors report one case of giant neglected OMC associated with DWS in an 18-month-old female child. To the best of our knowledge, only three cases of giant OMC with DWS have been described in world literature.

Case Report

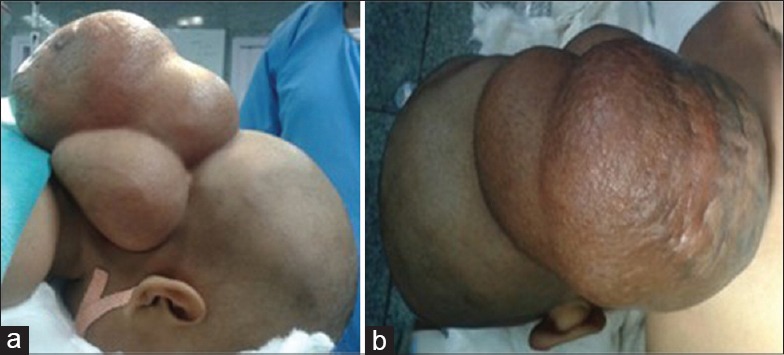

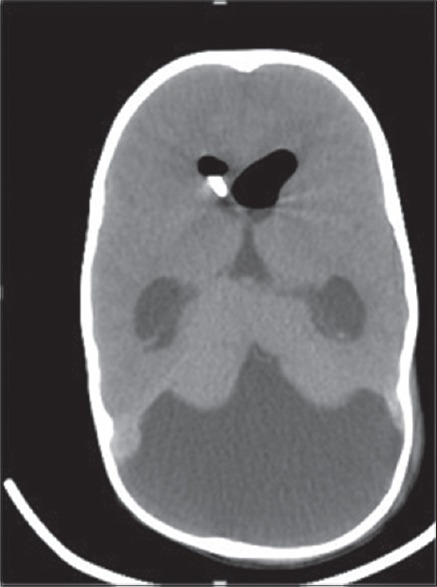

An 18-month-old female child reported to our outpatient department services with complaints of progressively increasing occipital cystic swelling since birth. The child was born as a result of cesarean section at term of nonconsanguineous parents. There was no family history of any congenital malformation or neural tube defect. The swelling used to increase in size with crying and coughing. On examination, a giant occipital swelling larger than the child's head was noted with a positive transillumination test. The child had delayed motor and social milestones. Noncontrast computed tomography head demonstrated a small defect (19 mm × 9.4 mm) in the occipital bone with a large swelling in the occipital region [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Clinical photographs (a and b) of the patient showing giant occipital meningocele

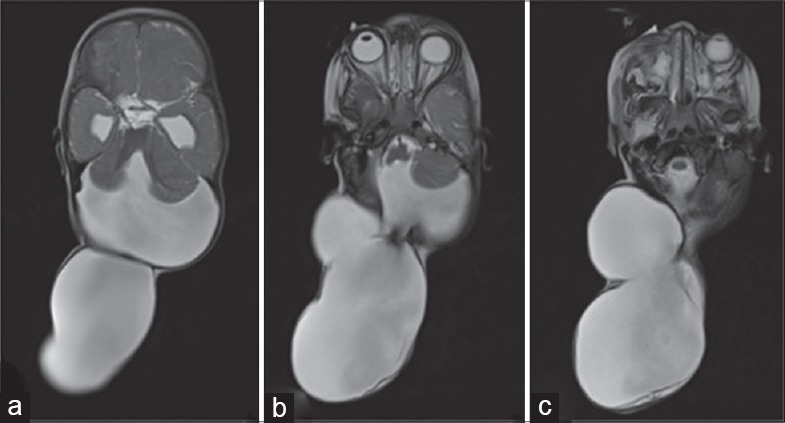

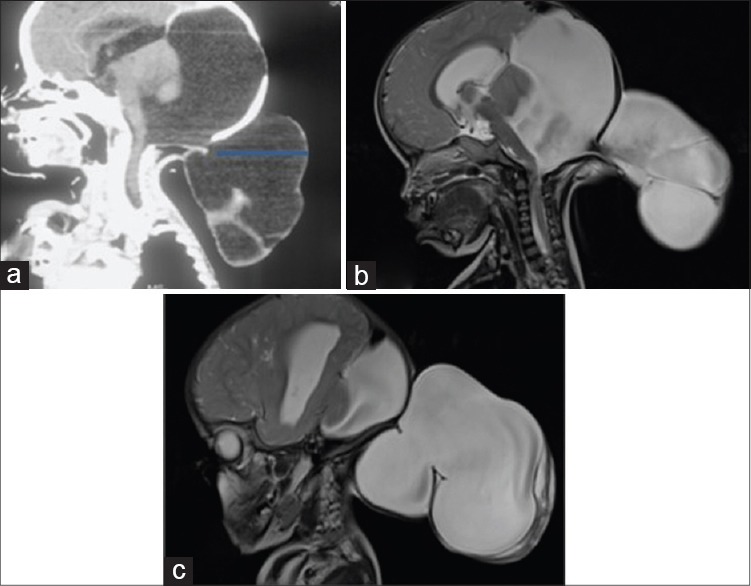

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain revealed a giant cystic CSF intensity swelling of size 12 cm × 11 cm × 8 cm in the occipital region communicating with a posterior fossa cyst through a small defect in the occipital bone suggestive of giant OMC. Large posterior fossa with torcular-lambdoid inversion, vermin hypoplasia, and a posterior fossa cyst communicating with the fourth ventricle along with dilation of all the ventricles was also noticed suggestive of DWS [Figures 2 and 3]. A neuroadiological diagnosis of DWS with a giant meningocele was made; however, screening of spine was unremarkable. No antenatal radiological tests were performed. All hematological investigations were normal.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain T2-weighted images, axial section image (a-c) a large posterior fossa cyst with vermin aplasia and a communicating giant occipital meningocele

Figure 3.

Saggital, computed tomography scan head (a) a small occipital bony defect (arrow) with a giant occipital meningocele. Saggital T2-weighted images (b and c) a giant occipital meningocele communicating with a large posterior fossa cyst and torcular-lambdoid inversion

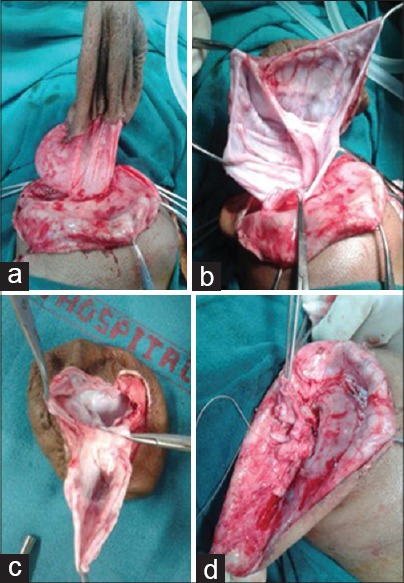

The child was taken for surgery under general anesthesia in prone position with a plan of meningocele repair followed by ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery. As the large size of meningocele was causing difficulty in intubation and positioning, meningocele repair was planned followed by shunt surgery. The meningocele sac was slowly decompressed by draining around 800 ml of clear CSF. A linear incision was given over the sac, and the dural margins were defined all around. The meningocele sac was separated from the occipital bone defect. Finally, the dura was incised, and the meningocele sac entered. No neural elements were seen inside the sac suggestive of meningocele. Intraoperatively, communication between meningocele and posterior fossa cyst and fourth ventricle was visualized. Meningocele sac along with redundant dura was excised, and dural edges were approximated to achieve a primary watertight closure. The preexisting small occipital bone defect was repaired using autologous split calvarial graft to provide a good cosmetic result. The redundant skin was also excised and closed esthetically in layers. However, the child developed hypothermia, so shunt surgery was deferred to the next day; however, an external ventricular drain was placed and the next morning the child underwent shunt surgery [Figures 4 and 5].

Figure 4.

Intraoperative photographs (a-d) showing dissection and repair of giant occipital meningocele

Figure 5.

Postoperative computed tomography scan head showing complete repair of gi ant occipital meningocele with right ventricular catheter in situ

Discussion

Hydrocephalous due to posterior fossa cyst and cerebellar hypoplasia was first described by Sutton in 1887.[5,6] Blackfan and Dandy in 1914 attributed it to obstruction at the level of foramen of Luschka and Magendie.[4,5,7,8] The Dandy syndrome classically consists of cystic dilation of the fourth ventricle, hypoplasia or aplasia of vermis associated with posterior fossa enlargement, and torcular-lambdoid inversion.[9,10,11,12] The current case had all the classical findings of DWS.

Cranial meningocele is characterized as herniation of only meninges whereas encephalocele includes herniation of meninges and neural tissue.[3,13,14] The term “cephalocele” includes both of these malformations. The association between DWS and meningocele is rare and about forty cases have been reported previously.[7,12,15,16] This developmental defect usually occurs around 6th or 7th week of intrauterine development.[1,2,4]

Bindal et al. in their series of fifty cases of DWS could find only 11 cases associated with OMS; however, none of the OMCs were sized to giant.[2] Mohanty et al. did not find even a single case of DWS with associated OMS in their large series of 72 cases.[1] Extra-gigantic meningocele larger than patients' head is further rare, and till date, only three cases of DWS associated with OMS have been described in literature.[8,16,17] The incidence shows a declining trend due to extensive use of antenatal sonography and subsequent subjecting to medical termination of pregnancy if neural tube defect is detected.[1,2] The presence of huge swelling immediately brings the patient to medical assistance; however, the family could not seek timely medical advice due to poor socioeconomic status. No antenatal ultrasonography screening or hematological tests were performed and the mother was unaware of fetus condition due to illiteracy and extreme poverty.

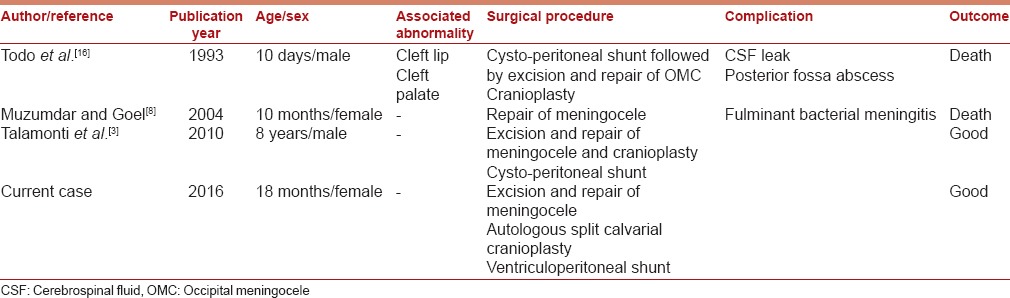

Surgical treatment should be performed on an urgent basis within few days of birth for giant cephalocele to mitigate the risk of rupture and nursing care inconveniences and psychological parental disturbances [Table 1]. With the advances in microsurgery and neuroanesthesia, surgical complications have reduced tremendously.[1,10,11,18,19] Bindal et al. advocated shunt as the first modality of treatment in cases of DWS with OMC, however 6 out of 11 patients in their series still required surgical repair of OMC.[2] However, a small or atretic OMC with DWS may be managed with only a shunt; however, giant OMC with DWS almost always requires surgical repair along with either a cystoperitoneal or ventriculoperitoneal shunt or rarely combined supra- and infra-tentorial shunt.[1,2,4]

Table 1.

Literature review for cases of Dandy-Walker syndrome with giant occipital meningocele

The pressure effects caused by hydrocephalous are usually mitigated by the presence of the open fontanelle, meningocele communicating through cranial defect.[2,4,5,17] However, the presence of incomplete septations in the meningocele acts as unidirectional ball valve mechanism promoting unidirectional escape of CSF from cranial cavity and promoting progressive enlargement of the meningocele sac, which puts difficulty in the nursing care of the child. The repair of OMC alters CSF flow dynamics and also further diminishes surface area for CSF resorption.[20] There are no clear guidelines for deciding between cysto-peritoneal and ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Intellectual outcomes usually remain suboptimal in patients with DWS as more than 50% of patients have subnormal intelligence.[1,2,4,10] The long-term outcome of DWS depends on the presence of associated abnormalities and is generally poor with 26%–50% of morbidity.[1,2,4,6,11,21] CSF diversion surgery always carries a risk of delayed complications such as shunt block and meningitis, and patients require long-term regular neurosurgical follow-up to pick up early shunt complication and monitoring of neurological status.

Warf et al. analyzed 45 cases with Dandy–Walker complex, which includes a continuum of congenital anomalies comprising Dandy–Walker malformation (25 cases), Dandy–Walker variant (17 cases), and mega cisterna magna (3 cases), who were treated with combined endoscopic third ventriculostomy and cauterization of choroid plexus which was successful in 74% of cases, and none of the above cases needed posterior fossa shunting and reported that the associated aqueductal stenosis is an uncommon association.[22]

A trial of endoscopic third ventriculostomy provides an optimal alternative to ventriculoperitoneal shunting in the surgical centers equipped with endoscopic facility and trained surgical team.

Conclusion

Early surgical treatment should be offered to patients with giant OMC associated with Dandy–Walker malformation. All efforts should be made to diagnose cranial or spinal dysraphism during antennal screening using sonography, making antenatal screening for congenital malformation mandatory through legislation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Mohanty A, Biswas A, Satish S, Praharaj SS, Sastry KV. Treatment options for Dandy-Walker malformation. J Neurosurg. 2006;105(5 Suppl):348–56. doi: 10.3171/ped.2006.105.5.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bindal AK, Storrs BB, McLone DG. Occipital meningoceles in patients with the Dandy-Walker syndrome. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:844–7. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199106000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talamonti G, Picano M, Debernardi A, Bolzon M, Teruzzi M, D'Aliberti G. Giant occipital meningocele in an 8-year-old child with Dandy-Walker malformation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2011;27:167–74. doi: 10.1007/s00381-010-1154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh R, Dogra N, Jain P, Choudhary S. Dandy Walker syndrome with giant occipital meningocele with craniovertebral anomalies: Challenges faced during anaesthesia. Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60:71–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.174811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dandy WE. An experimental and clinical study of internal hydroccephalus. J Am Med Assoc. 1913;61:2216. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sautreaux JL, Giroud M, Dauvergne M, Nivelon JL, Thierry A. Dandy-Walker malformation associated with occipital meningocele and cardiac anomalies: A rare complex embryologic defect. J Child Neurol. 1986;1:64–6. doi: 10.1177/088307388600100112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cakmak A, Zeyrek D, Cekin A, Karazeybek H. Dandy-Walker syndrome together with occipital encephalocele. Minerva Pediatr. 2008;60:465–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muzumdar DP, Goel A. Giant occipital meningocele as a presenting feature of Dandy-Walker syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:863–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishimaki S, Yoda H, Seki K, Kawakami T, Akamatsu H, Iwasaki Y. A case of Dandy-Walker malformation associated with occipital meningocele, microphthalmia, and cleft palate. Pediatr Radiol. 1990;20:608–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02129071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kojima T, Waga S, Shimizu T, Sakakura T. Dandy-Walker cyst associated with occipital meningocele. Surg Neurol. 1982;17:52–6. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(82)90043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki Y, Mimaki T, Tagawa T, Seino Y, Ohmichi M, Sugita N, et al. Dandy-Walker cyst associated with occipital meningocele. Pediatr Neurol. 1989;5:191–3. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(89)90071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shenoy RD, Kamath N. Dandy-Walker malformation, occipital meningoencephalocele, meso-axial polydactyly and bifid hallux. Clin Dysmorphol. 2010;19:166–8. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32833a77f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahapatra AK. Giant encephalocele: A study of 14 patients. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2011;47:406–11. doi: 10.1159/000338895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Satyarthee GD, Mahapatra AK. Craniofacial surgery for giant frontonasal encephalocele in a neonate. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9:593–5. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shuto T, Sekido K, Ohtsubo Y, Saida A, Yamamoto I. Dandy-Walker syndrome associated with occipital meningocele and spinal lipoma – Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1999;39:544–7. doi: 10.2176/nmc.39.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Todo T, Usui M, Araki F. Dandy-Walker syndrome forming a giant occipital meningocele – Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1993;33:845–50. doi: 10.2176/nmc.33.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexiou GA, Sfakianos G, Prodromou N. Diagnosis and management of cephaloceles. J Craniofac Surg. 2010;21:1581–2. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181edc3f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Black SA, Galvez JA, Rehman MA, Schwartz AJ. Images in anesthesiology: Airway management in an infant with a giant occipital encephalocele. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:1504. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31829f028a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh N, Rao PB, Ambesh SP, Gupta D. Anaesthetic management of a giant encephalocele: Size does matter. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2012;48:249–52. doi: 10.1159/000346904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verma SK, Satyarthee GD, Singh PK, Sharma BS. Torcular occipital encephalocele in infant: Report of two cases and review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2013;8:207–9. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.123666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osenbach RK, Menezes AH. Diagnosis and management of the Dandy-Walker malformation: 30 years of experience. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1992;18:179–89. doi: 10.1159/000120660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warf BC, Dewan M, Mugamba J. Management of Dandy-Walker complex-associated infant hydrocephalus by combined endoscopic third ventriculostomy and choroid plexus cauterization. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8:377–83. doi: 10.3171/2011.7.PEDS1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]