Abstract

The opsoclonus-myoclonus ataxia syndrome (OMAS) also called “Kinsbourne syndrome” or “dancing eye syndrome” is a rare but serious disorder characterized by opsoclonus, myoclonus, and ataxia, along with extreme irritability and behavioural changes. Data on its epidemiology, clinical features, and outcome are limited worldwide. The aim of the study was to evaluate the clinical profile and outcome of children with OMAS. A retrospective data of all children presented to Pediatric oncology clinic with a diagnosis of opsoclonus-myoclonus from 2013 to 2016 were collected. 6 patients with a diagnosis of OMAS were presented over a 4-year period. All 6 cases had paraneoplastic etiology. All Children had good outcome without any relapse. Paraneoplastic opsoclonus myoclonus had a good outcome in our experience.

Key words: Children, neuroblastoma, opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome, paraneoplastic syndrome

Introduction

Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome (OMAS), also called “Kinsbourne syndrome” or “dancing eye syndrome,” is a serious, rare, and often chronic neurological disorder. OMAS consists of three main symptoms: Opsoclonus (conjugate, multidirectional, chaotic eye movements), myoclonus (nonepileptic limb jerking that can also involve the head and face) and truncal ataxia, which cause gait imbalance. Sleep disturbance, cognitive dysfunction, and behavioral changes are often found.[1]

Age of onset is typically seen before 3 years of age. OMAS is generally a paraneoplastic or parainfectious entity, but in children, it is most commonly associated with occult neuroblastoma (NB) in about 50% of cases and between 2% and 3% of children with NB have OMAS.[2,3] Although most patients with NB and OMAS have good survival rates, 70%–80% of these children will have long-term neurologic sequelae.[4,5]

In pediatric age, OMAS may be associated with neuroblastic tumors (NB, ganglioneuroblastoma, or ganglioneuroma). Occasionally, it has been described with other entities as ovarian teratoma or hepatoblastoma.[6,7]

The diagnosis of OMAS may be difficult in some patients and should be considered even when only some of the features are present. International consensus has described three of the following four diagnostic criteria should be present to describe the typical syndrome: (1) Opsoclonus, (2) myoclonus/ataxia, (3) behavioral change and/or sleep disturbance, and (4) NB.[8]

We present a retrospective study of five children presented to the pediatric oncology clinic (POC) of All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) with a diagnosis of opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome (OMS). The objective of this study was to describe the clinical profile and outcome of this disorder.

Methods

The medical records of all children presented to POC, Department of Pediatrics, AIIMS, with a diagnosis of opsoclonus-myoclonus were retrieved and reviewed. Details of clinical symptoms, investigations, and treatment were recorded. The diagnosis of opsoclonus-myoclonus was based on a constellation of any three of the four clinical features: Opsoclonus, myoclonus, ataxia, and encephalopathy/irritability/behavioral change/sleep disturbance.[8] Outcome was assessed on follow-up by direct assessment and by telephonic communication (in one patient).

Results

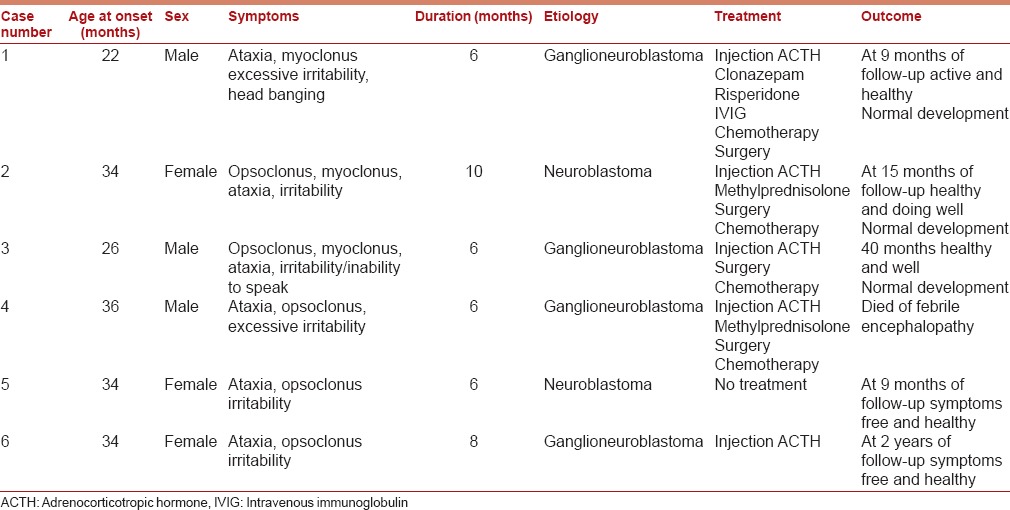

A total of six patients with a diagnosis of opsoclonus-myoclonus were admitted over 4-year period [Table 1]. The median age at clinical presentation was 34 months (range 22–36 months). The male:female ratio was 1:1. Before the onset of symptoms, all children had normal development. Opsoclonus, myoclonus, ataxia, and encephalopathy/behavioral abnormalities (irritability/sleep disturbance) were present in all children at presentation. All six children had symptoms of moderate to severe. The duration of symptoms at the time of presentation was in the range of 6–10 months.

Table 1.

Clinical profile and outcome in six children with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome

The reasons for the delay in diagnosis included misdiagnosis by peripheral physicians and delayed referral to our center.

All children had paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus (two left paravertebral ganglioneuroblastoma, two left paravertebral NB, one left paravertebral plus left psoas muscle ganglioneuroblastoma, and one right paravertebral ganglioneuroblastoma) [Figures 1–3]. Onset of OMAS preceded the diagnosis of malignant tumor in all cases. The diagnosis of tumor was made on contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis (3 CT scan and 3 MRI). All children had normal abdominal ultrasound. Tests for urinary excretion of vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) were negative in all cases. Iodine-131 metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy scan (I-131 MIBG) was performed in all cases, but it detected MIBG concentrating tumor only in two cases.

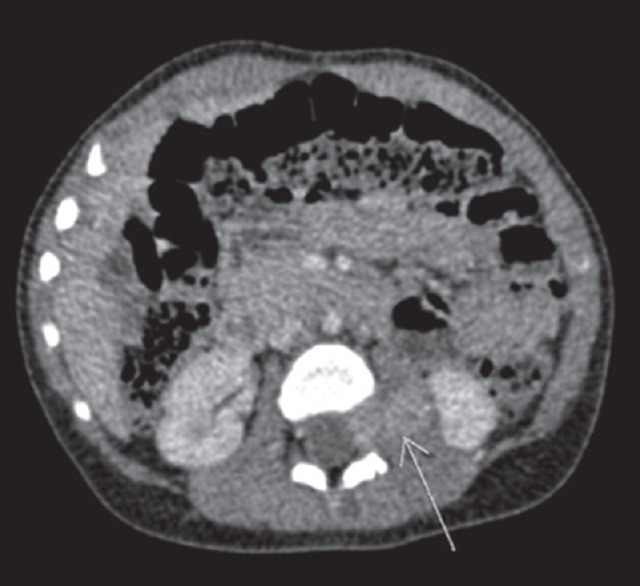

Figure 1.

(Case 2) (Original) Axial section showing well-defined enhancing soft-tissue mass lesion (3.5 cm × 2 cm × 1.4 cm) seen in the left upper psoas muscle extending into left neural foramen in between L2 and L3 vertebra up to dura mater

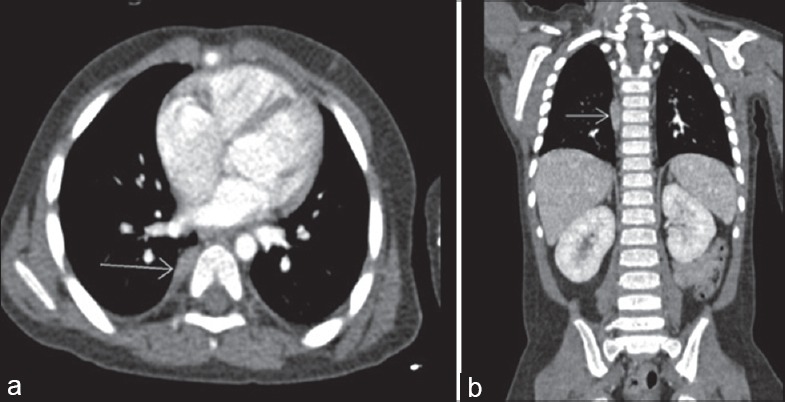

Figure 3.

(a and b) (Case 5) Axial and coronal section showing well-defined left paravertebral mass lesion 2 cm × 1.8 cm × 2.9 cm at the level of D6 to D8 vertebral body

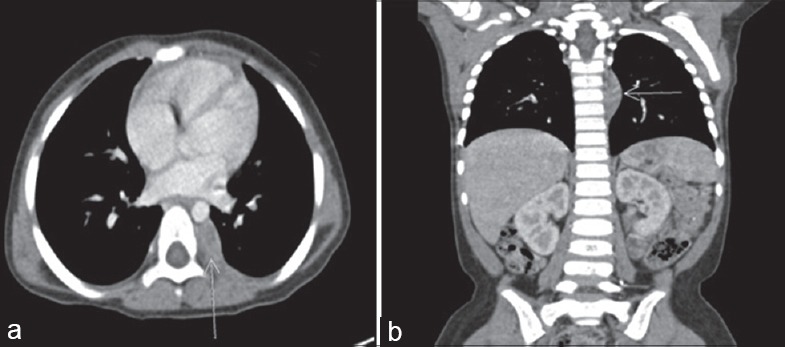

Figure 2.

(a and b) (Case 3) Axial section and coronal section showing right paravertebral mass of size 1.5 cm × 0.6 cm × 2.4 cm at the level of D6 to D8 vertebral body

An initial diagnosis of OMAS was made in all children. Three children received injection adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH); two children received injection ACTH plus injection methylprednisolone followed by oral steroids over 4 weeks. One child (case 1) also received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and oral clonazepam and risperidone in view of abnormal behavior (excessive irritability, biting, and head banging). All children had a good response and recovered completely by 4 weeks. One child (case 5) had spontaneous improvement and complete recovery without specific immunomodulator therapy.

Of the six cases with paraneoplastic OMS, four cases were treated with surgical resection of tumor and chemotherapy. In one child (case 5), treatment was deferred by parents but on telephonic communication that the child was symptoms free and healthy at 9 months after presentation to us. In another case (case 6), she received only injection ACTH, surgery, and chemotherapy were denied by parents. After follow-up of 24 months, the child was asymptomatic, but CT of the abdomen revealed mass of same size that was documented 2 years back. One child (case 3) died of febrile encephalopathy (not related to disease). All four cases that got proper treatment had normal development on follow-up. Two children (case 5 and case 6) had mild developmental delay.

Discussion

OMS was first described by Marcel Kinsbourne in 1962.[9] Other names for OMS include OMAS, paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus ataxia, Kinsbourne syndrome, myoclonic encephalopathy of infants, dancing eyes-dancing feet syndrome, and dancing eyes syndrome.

In our study, all six children were between 2 and 3 years of age, similar to the trend seen in other reports, in which OMA was uncommonly diagnosed before 1 year of age.[10,11] One possible explanation for the low incidence in infancy may be due to ability to develop specific antibodies is less in younger infants. We observed, alike to previously published studies, a similar median age at clinical presentation, acute/subacute onset of presentation, association of NB, and response to immunomodulator therapy.[12,13]

We have found poor sensitivity of urine VMA in our case series with similar findings reported by Brunklaus et al.[14] We also observed poorer sensitivities for MIBG scintigraphy scan in contrast with the reported high sensitivity (up to 95%) for detection of NB as compared to an abdominal CT scan/MRI.

In adults, OMS is seen in relation to malignancies of the breast and lung (small cell carcinoma), in association with antibodies which are directed against an RNA binding antigen from the anti-Hu antibody.[15] This antibody is not found in children in OMS of NB. In children, NB which presents with OMS is more mature, shows a favorable histology, and absence of N-myc oncogene amplification than tumors which occur without symptoms of OMS.[16]

OMS, the most frequent paraneoplastic syndrome in pediatric age group, remains a challenge for treatment. Various immunomodulatory therapies have been used including steroids, IVIG, cyclophosphamide, and more recently, rituximab.[17]

Patients with NB and OMA have been reported to have excellent survival.[5,10,11] According to Children's Cancer Group data, the 3-year survival rate for children with nonmetastatic NB and OMA was 100% (reported from 675 patients who were diagnosed between 1980 and 1994) in compared to 77% in non-OMA.[3]

Singhi et al. described a case series of 11 patients (largest case series from India) with a diagnosis of opsoclonus-myoclonus (of the 11, 4 had paraneoplastic etiology) and concluded that children with paraneoplastic opsoclonus had more relapses and had a poor outcome as compared to an idiopathic group.[18] In contrast to study of Singhi et al., in our series, all six children had paraneoplastic OMS, and all had good outcome. This tumor is known to have spontaneous regression. Our one child (case 5) had spontaneous symptomatic resolution, and another child (case 6) is doing well without surgery and chemotherapy.

We have seen a good therapeutic response with immunomodulators, including ACTH, IVIG, and corticosteroids. Because of the small number of patients, it is difficult to compare these therapies. No one had relapse in our series contradicting to those reported by Tate et al. (up to 52%)[13] could be due to the small number of patients in our study.

In most children with NB, the characteristic feature is the response of this syndrome to corticosteroids and ACTH and the resolution of the neurological signs when the NB is treated. Children often develop lifelong neurologic sequelae that impair motor, cognitive, language, and behavioral developments.[3] Papero et al. observed that in older children, late effects are less likely seen because basic motor and cognition have already been formed.[19] Rudnick et al. reported that children with more advanced stage disease had better outcomes with regard to neurologic sequelae. One possible explanation for this association may be that patients with advanced stage disease require more intensive therapy that usually includes chemotherapy.[3] Russo et al. suggested that chemotherapy may improve neurologic outcome in children with OMA and NB, possibly due to its immunosuppressive effects.[5] In our study, five children with OMS responded with ACTH and steroids; one child recovered spontaneously. Two children had neurodevelopment deficits (mild developmental delay). The outcome was good in our all children, whereas in the study by Tate et al., the outcome was independent of etiology. Other studies[3,18,20] have also observed better outcome of idiopathic opsoclonus-myoclonus. We did not observe progressive developmental and behavioral problems in our patients, which could be due to small number of patients and short follow-up.

Conclusion

OMS is a rare disorder, but it affects children more frequently than adults and exhibits an excellent rate of survival. Screening for an occult NB is necessary in all children with this syndrome. I-131 MIBG scan and urinary VMA have poor sensitivity. OMS (paraneoplastic) had a good outcome without significant neurological deficits in our experience.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Digre KB. Opsoclonus in adults. Report of three cases and review of the literature. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:1165–75. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1986.00520110055016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pranzatelli MR. The neurobiology of the opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1992;15:186–228. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudnick E, Khakoo Y, Antunes NL, Seeger RC, Brodeur GM, Shimada H, et al. Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome in neuroblastoma: Clinical outcome and antineuronal antibodies-a report from the children's cancer group study. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:612–22. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Grandis E, Parodi S, Conte M, Angelini P, Battaglia F, Gandolfo C, et al. Long-term follow-up of neuroblastoma-associated opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome. Neuropediatrics. 2009;40:103–11. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Russo C, Cohn SL, Petruzzi MJ, de Alarcon PA. Long-term neurologic outcome in children with opsoclonus-myoclonus associated with neuroblastoma: A report from the Pediatric Oncology Group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;28:284–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199704)28:4<284::aid-mpo7>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitzpatrick AS, Gray OM, McConville J, McDonnell GV. Opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome associated with benign ovarian teratoma. Neurology. 2008;70:1292–3. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000308947.70045.7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sahu JK, Prasad K. The opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Pract Neurol. 2011;11:160–6. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2011-000017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthay KK, Blaes F, Hero B, Plantaz D, De Alarcon P, Mitchell WG, et al. Opsoclonus myoclonus syndrome in neuroblastoma a report from a workshop on the dancing eyes syndrome at the advances in neuroblastoma meeting in Genoa, Italy, 2004. Cancer Lett. 2005;228:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kinsbourne M. Myoclonic encephalopathy of infants. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1962;25:271–6. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.25.3.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altman AJ, Baehner RL. Favorable prognosis for survival in children with coincident opso-myoclonus and neuroblastoma. Cancer. 1976;37:846–52. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197602)37:2<846::aid-cncr2820370233>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koh PS, Raffensperger JG, Berry S, Larsen MB, Johnstone HS, Chou P, et al. Long-term outcome in children with opsoclonus-myoclonus and ataxia and coincident neuroblastoma. J Pediatr. 1994;125(5 Pt 1):712–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pang KK, de Sousa C, Lang B, Pike MG. A prospective study of the presentation and management of dancing eye syndrome/opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome in the United Kingdom. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010;14:156–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tate ED, Allison TJ, Pranzatelli MR, Verhulst SJ. Neuroepidemiologic trends in 105 US cases of pediatric opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2005;22:8–19. doi: 10.1177/1043454204272560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunklaus A, Pohl K, Zuberi SM, de Sousa C. Investigating neuroblastoma in childhood opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:461–3. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.204792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dropcho EJ. Paraneoplastic Opsoclonus in Adults. Clinical Summary. MedLink Corporation. [Last retrieved on 2012 May 18]. Available from: http://www.medlink.com/medlinkcontent.asp.

- 16.Cooper R, Khakoo Y, Matthay KK, Lukens JN, Seeger RC, Stram DO, et al. Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome in neuroblastoma: Histopathologic features-a report from the children's cancer group. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:623–9. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krug P, Schleiermacher G, Michon J, Valteau-Couanet D, Brisse H, Peuchmaur M, et al. Opsoclonus-myoclonus in children associated or not with neuroblastoma. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2010;14:400–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singhi P, Sahu JK, Sarkar J, Bansal D. Clinical profile and outcome of children with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:58–61. doi: 10.1177/0883073812471433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Papero PH, Pranzatelli MR, Margolis LJ, Tate E, Wilson LA, Glass P. Neurobehavioral and psychosocial functioning of children with opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1995;37:915–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1995.tb11944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bataller L, Graus F, Saiz A, Vilchez JJ. Spanish Opsoclonus-Myoclonus Study Group. Clinical outcome in adult onset idiopathic or paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus. Brain. 2001;124(Pt 2):437–43. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.2.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]