Abstract

This article continues an “Unreported Intrinsic Disorder in Proteins” series, the goal of which is to expose some interesting cases of missed (or overlooked, or ignored) disorder in proteins. The need for this series is justified by the observation that despite the fact that protein intrinsic disorder is widely accepted by the scientific community, there are still numerous instances when appreciation of this phenomenon is absent. This results in the avalanche of research papers which are talking about intrinsically disordered proteins (or hybrid proteins with ordered and disordered regions) not recognizing that they are talking about such proteins. Articles in the “Unreported Intrinsic Disorder in Proteins” series provide a fast fix for some of the recent noticeable disorder overlooks.

Keywords: disorder prediction, intrinsically disordered protein, intrinsically disordered protein region, molecular recognition, posttranslational modifications, protein-protein interactions

Introduction

There is no need to emphasize the biological importance of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), intrinsically disordered protein regions (IDPRs), and hybrid proteins containing both ordered and disordered regions. This is a truism reflected in the exponentially increasing number of papers dedicated to these proteins and further enlightened in the articles of the “Digested Disorder” series published in this journal.1-3 Although papers knowingly dedicated to IDPs and hybrid proteins are many, there are still numerous publications in which this concept is overlooked, or missed or simply ignored. In order to bring attention of researchers to this widespread phenomenon of missed (or overlooked, or ignored, or unreported) disorder, this journal initiated a new series of papers entitled “Unreported Intrinsic Disorder in Proteins.”4 In the first paper of the series, potential implications of missed disorder were considered based on the analysis of 42 papers published in Biochemistry and the Journal of Molecular Biology during 2013–2014. Those 42 “hidden gems” contained information on 143 proteins, whose extent of intrinsic disorder ranged from 10% to 100%.4 The strategy was elaborated to stress the idea that by ignoring the body of work on IDPs, such publications with missed intrinsic disorder often fail to relate their findings to prior discoveries or fail to explore the obvious implications of their work. The mentioned strategy was based on a brief review of each of these very interesting and important papers, on pointing out how each paper is related to the IDP field, and on showing how common tools elaborated in the IDP field can help taking the findings to new directions or provide a broader context for the reported findings.4

Recognizing that reading numerous pages dedicated to the description of tens and hundreds of proteins represents a tedious task, and that “missed disorder” phenomenon continues to be rather common in the modern protein literature, a new strategy is elaborated here to continue enlightening this phenomenon. Instead of analyzing many papers talking about many overlooked IDPs, each new article in the “Unreported Intrinsic Disorder in Proteins” series will consider only a handful of papers that talk about IDPs or hybrid proteins not recognizing that they are talking about such proteins. In essence, we are talking about “Disorder Emergency Room” that provides a fast fix for some of the recent noticeable disorder overlooks and shows how the consideration of intrinsic disorder can be used to strengthen conclusions.

The sections in this article are organized in the following way: first, a brief description of the paper is provided; then, the biological importance of the related proteins is discussed; next, the results of the computational and bioinformatics analyses of the disorder status of a given protein (or set of proteins) are represented to show how consideration of intrinsic disorder can enhance conclusions of a given paper.

Tools Used in This Study

Disorder predictions

The propensity of a given protein for intrinsic disorder was evaluated by a family of PONDR predictors. Here, scores above 0.5 were considered to correspond to disordered residues/regions. PONDR® VSL2B is one of the more accurate stand-alone disorder predictors,5 and based on the comprehensive assessment of in silico predictors of intrinsic disorder,6,7 this tool was shown to perform reasonably well. PONDR® VL3 possesses high accuracy in finding long IDPRs,8 PONDR® VLXT is not the most accurate predictor but has high sensitivity to local sequence peculiarities which are often associated with disorder-based interaction sites,9 whereas PONDR-FIT represents a metapredictor which, being moderately more accurate than each of the component predictors, is one of the most accurate disorder predictors.10 A novel IDPR predictor, DISOPRED3 (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/disopred/), was also used.11 DISOPRED3 is claimed to be the state of the art in the identification of IDPRs, which is significantly improved over the previous version, DISOPRED2, and is further enhanced with the annotation of predicted binding sites,11 which are termed DP3IBS (DISOPRED3 identified binding sites) here.

Disorder evaluations for target proteins were further enhanced by utilizing the outputs of the MobiDB database (http://mobidb.bio.unipd.it/)12,13 that generates consensus disorder scores based on the outputs of 10 disorder predictors, such as ESpritz in its 3 flavors,14 IUPred in its 2 flavors,15 DisEMBL in 2 of its flavors,16 GlobPlot,17 PONDR® VSL2B,5,18 and JRONN.19

Where available, important disorder-related and functional information was also retrieved from D2P2 (http://d2p2.pro/), which is a database of predicted disorder that represents a community resource for pre-computed disorder predictions on a large library of proteins from completely sequenced genomes.20 D2P2 database uses outputs of PONDR® VLXT,9 IUPred,15 PONDR® VSL2B,5,18 PrDOS,21 ESpritz,14 and PV2.20 This database is further enhanced by information on the curated cites of various posttranslational modifications and on the location of predicted disorder-based potential binding sites.

Interactivity analysis of target proteins with STRING

Where available, the interactivity of a given protein was evaluated by STRING (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes), which is the online database resource, that provides both experimental and predicted interaction information.22 STRING produces the network of predicted associations for a particular group of proteins. The network nodes are proteins, whereas the edges represent the predicted or known functional associations. An edge may be drawn with up to 7 differently colored lines that represent the existence of the 7 types of evidence used in predicting the associations. A red line indicates the presence of fusion evidence; a green line-neighborhood evidence; a blue line-co-occurrence evidence; a purple line-experimental evidence; a yellow line-text mining evidence; a light blue line-database evidence; a black line-co-expression evidence.22

Molecular recognition features (MoRFs)

Being defined as a short order-prone motif within a long disordered region and being able to undergo disorder-to-order transition during the binding to a specific partner, Molecular Recognition Feature (MoRF) usually has much higher content of aliphatic and aromatic amino acids than disordered regions in general. Due to these peculiarities, MoRF regions are frequently observed as sharp dips in the corresponding plots representing per-residue distribution of PONDR® VL-XT disorder scores. Hence, based on the PONDR® VL-XT prediction and a number of other attributes, the MoRF regions can be identified.23,24 In addition to PONDR-based predictors of α-MoRFs; i.e., short disordered regions that undergo a transition to a-helix at binding to a specific partner, a newer computational tool MoRFpred, which identifies all MoRF types (α, β, coil and complex), was also utilized.25

ANCHOR analysis

In addition to MoRF identifiers, potential binding sites in disordered regions can be identified by the ANCHOR algorithm.26,27 This approach relies on the pairwise energy estimation approach developed for the general disorder prediction method IUPred,15,28 being based on the hypothesis that long regions of disorder contain localized potential binding sites that cannot form enough favorable intrachain interactions to fold on their own, but are likely to gain stabilizing energy by interacting with a globular protein partner.26,27 The term ANCHOR-indicated binding site (AIBS) is used to identify a region of a protein suggested by the ANCHOR algorithm to have significant potential to be a binding site for an appropriate but typically unidentified partner protein.

Disorder Emergency Room

Table 1 represents basic structural information retrieved for a new set of proteins with overlooked disorder. Proteins in this table are arranged by their amount of predicted intrinsic disorder.Table 1 shows that although the amount of predicted disorder in these proteins ranges from ∼20 to >80%, disordered regions are likely to be related to at least some functional aspects of these proteins. However, this issue was not addressed in the corresponding papers, thereby placing these proteins to the category of proteins with unreported disorder. More detailed description of each protein is presented below.

Table 1.

Basic structural information on proteins considered in this article

| Protein | UniProt ID | Length | PONDR scorea | MobiDB scoreb | IDPRsc | MoRFs | AIBSs | DP3IBSs | PDB ID (region) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SRY | Q05738 | 395 | 82.0 | 69.1 | 1–12, 45–62, 65–85, 132–376, 392–395 | 21–38 56–73 | 8–16, 38–43, 93–103, 118–139, 158–169, 181–228, 236–347, 363–377, 385–395 | 28–30 78–95 | |

| 4.1B/DAL-1 | Q9Y2J2 | 1,087 | 72.4 | 50.7 | 1–119, 238–244, 260–283, 303–307, 406–617, 668–862, 864–1087 | 46–63 72–89 421–438 455–472 724–741 748–765 810–828 881–898 957–974 | 1–9, 17–33, 42–58, 68–79, 111–118, 451–468, 491–514, 535–542, 566–574, 715–723, 727–749, 759–780, 792–819, 841–897, 908–918, 931–941, 951–977, 998–1009, 1033–1059, 1067–1077 | 402–405 1032–1043 1069–1074 1081–1085 | 2HE7 (108–390) |

| Cyclin A2 | P20248 | 432 | 50.0 | 31.0 | 1–181, 202–204, 400–420, 423–432 | 89–106 127–144 | 1–28, 43–62, 72–105, 123–134 | N/Fd | 1VIN (175–432) |

| TRPM7 | Q96QT4 | 1,895 | 34.1 | 14.8 | 1–9, 80–88, 186–196, 333–341, 479–484, 540–614, 667–683, 780–838, 1139–1198, 1228–1231, 1248–1268, 1298–1312, 1319–1553, 1568–1600, 1517–1621, 1692–1696, 1729–1737, 1781–1785, 1812–1865e | 551–568 578–595 1510–1527 1822–1839 1848–1865 | 579–584, 1313–1320, 1328–1333, 1369–1380, 1437–1449, 1457–1462, 1474–1491, 1513–1523, 1548–1560, 1860–1865 | 28–35 59–70 74–76 594–611 1158–1163 1193–1195 1830–1833 1841–1843 1850–1852 | 1IA9 (1549–1828 in mouse protein, UniProt ID: Q923J1) |

| TRPM6 | Q9BX84 | 2,022 | 33.0 | 14.1 | 1–20, 29–36, 73–94, 100–104, 186–198, 237–241, 387–390, 480–486, 544–601, 651–669, 765–774, 783–821, 1000–1006, 1035–1042, 1125–1133, 1138–1180, 1234–1249, 1281–1342, 1398–1444, 1471–1522, 1540–1549, 1557–1568, 1575–1596, 1601–1625, 1660–1715, 1746–1779, 1884–1897, 1937–1942, 1978–2022 | 1457–1474 1516–1533 1547–1565 1589–1606 1980–1997 | 534–543, 1257–1262, 1275–1283, 1339–1352, 1423–1429, 1444–1459, 1464–1475, 1525–1532, 1549–1558, 1594–1601, 1626–1632, 1652–1660, 1963–1975, 1992–2000 | 1–10 76–80 191–103 537–549 561–562 580–588 1169–1170 1675–1685 1688–1689 1692–1701 1986–1987 1993–2009 | |

| DpsC | Q9K3L0 | 200 | 30.0 | 20.0 | 1–28, 122–140, 161–168, 196–200 | N/F | 146–154 | 1–32 | 4CYB |

| DpsA | Q9R408 | 187 | 19.3 | 16.0 | 1–7, 131–135, 164–187 | N/F | N/F | 1–6 165–187 | 4CYA |

aPONDR disorder score is a per cent of disordered residues in a given protein predicted by the PONDR® VSL2 predictor.

bConsensus disorder content of a given protein (% disordered residues) evaluated by MobiDB (http://mobidb.bio.unipd.it/).12 This consensus obiDB disorder score is based on the outputs of 10 disorder predictors, such as ESpritz in its 3 flavors,14 IUPred in its 2 flavors,15 DisEMBL in 2 of its flavors,16 GlobPlot,17 PONDR VSL2,5,18 and JRONN.19

cLocations of IDPRs predicted by PONDR VSL2.

dN/F – not found.

eFor TRPM6 and TRP7 proteins, intracellular disordered regions are shown by bold font.

SRY and regulation of testicular differentiation

Tanaka and Nishinakamura provided a comprehensive overview of an important protein encoded by the Y-linked gene Sry (sex determination region on Y chromosome),29 which is known to play an important regulatory role in testicular differentiation, since expression of this protein in mammals shifts the bipotential embryonic gonad toward a testicular fate.30-32 The review represents the recent progress in understanding the mechanisms underlying genital ridge formation, the regulation of SRY expression, and functions of this important protein in male sex determination of mice.29 The authors emphasized that although the Sry gene was discovered in 1990, and although it is well recognized now that SRY is responsible for the induction of the pre-Sertoli cell differentiation that defines the testis differentiation of the bipotential gonad, the precise mechanisms underlying the sex determination of bipotential genital ridges and the mechanisms defining the Sry activation remain mostly elusive.29 Another level of complexity in the testis development is defined by the fact that several cell types such as Sertoli, Leydig, and spermatogonial cells have to arise from bipotential precursors present in the genital ridge.33 However, despite all these complications, a noticeable progress has been recently made in this field based on the mouse model studies.29

It has been emphasized that the development of functionally analogous organs, testis and ovary, that arose from a common primordial structure, is driven by very different programs of gene regulation and cellular organization.33 In fact, the formation and assembly of several cell types in the mammalian embryo is needed for the development of testes and ovaries. The precursor tissue, the genital ridge, contains bipotential precursors (gonads), and tightly controlled differentiation of somatic cells into Sertoli or granulosa cells defines the fate of the embryonic gonad. In such bipotential gonads, the formation of Sertoli cells promotes the testicular differentiation program, whereas formation of granulosa cells promotes the ovarian differentiation program.29,33 Importantly, expression of the Y-linked gene Sry and Sry-related HMGbox 9 gene Sox9 shifts the bipotential embryonic gonad toward a testicular fate.29,33 SRY and SOX9 proteins are members of the SOX family of developmental transcription factors containing a specific DNA-binding domain, the high-mobility group (HMG) box, crucial for binding of these transcription factors to the DNA consensus sequence (A/T)ACAA(T/A) with high affinity.34 Curiously, unlike most known transcriptional activators, SRY proteins from most species lack an obvious transactivation domain (TAD).35

Although structural information about mice SRY is very limited, significant knowledge is accumulated on structural properties of the HMG-box domains in general and on the structural properties of the several SOX proteins in particular.36 The characteristic feature of the HMG-box domains is their unusual L-shaped structure, where 3 α-helices and an N-terminal β-strand are packed to form major (that comprises α-helix 1, α-helix 2, the first turn of α-helix 3, and connecting loops) and minor wings comprising the N-terminal β-strand, the remainder of α-helix 3, and the C-terminal segment.36 It has been emphasized that An angular inner surface of this unusual L-shaped structure presents as a template for DNA bending.36

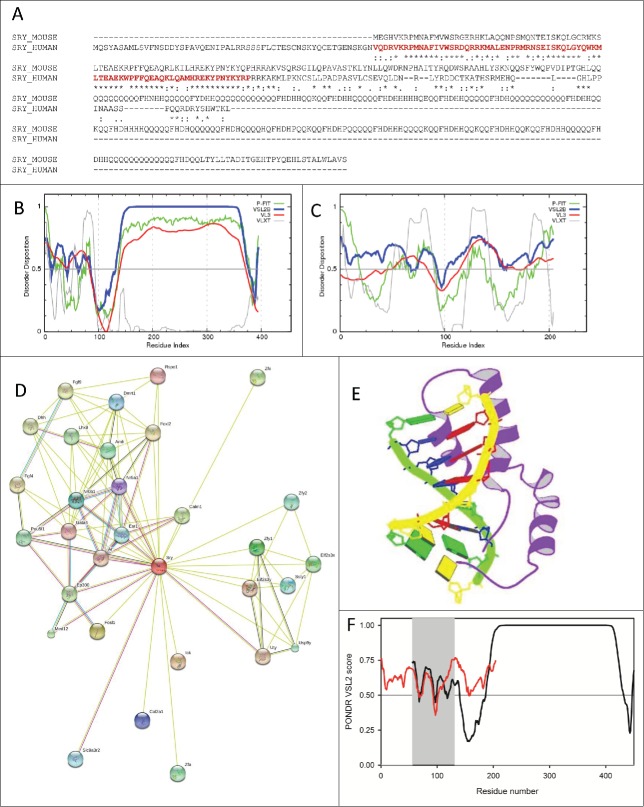

Curiously,Figure 1A shows that despite the fact that the HMG boxes of mouse and human SRY proteins are almost identical and that there is a high level similarity in their HMG-containing regions (among the 173 N-terminal residues of mouse SRY, 75, 34 and 9 residues are respectively identical, strongly similar and weakly similar to the C-terminal part of human SRY), mouse protein is almost fold2- longer than human SRY and contains an unusual C terminus comprising a bridge domain (residues 82–144) and a polyglutamine (polyQ) tract encoded by a CAG-repeat microsatellite.35 In Mus musculus, this polyQ tract consists of 21 blocks of 2 to 13 glutamine residues interspersed by a short histidine-rich spacer sequence (see Figure 1A). This “glutamine-rich domain” is known to be characteristic of the rodent SRY proteins and display noticeable length variation among mouse species.37,38 In general, it is assumed that there are 2 distinct groups of mammalian SRYs proteins, where proteins from the non-rodent mammals have a centrally-located HMG-box domain flanked by poorly conserved N- and C- terminal domains (NTD and CTD, respectively), and where proteins from the rodent species possess the N-terminally located HMG domain.35

Figure 1 (See previous page).

(A). Sequence alignment of mouse (UniProt ID: Q05738) and human SRY proteins (UniProt ID: Q05066) by CLUSTAL W.106 Bold red characters show the HMG-box domain of human protein. (B). Per-residue disorder distribution in the mouse SRY protein. Disorder propensity was evaluated by a set of predictors from the PONDR family, PONDR® FIT, VSL2B, VL3, and VLXT. (C). Per-residue disorder distribution in the human SRY protein. Disorder propensity was evaluated by a set of predictors from the PONDR family, PONDR® FIT, VSL2B, VL3, and VLXT. Scores above 0.5 correspond to disordered residues/regions. (D). Evaluation of the interactivity of the mouse SRY protein (UniProt ID: Q05738) by STRING, which is the online database resource Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes that provides both experimental and predicted interaction information.22 STRING produces the network of predicted associations for a particular group of proteins. The network nodes are proteins. The edges represent the predicted functional associations. An edge may be drawn with up to 7 differently colored lines - these lines represent the existence of the 7 types of evidence used in predicting the associations. A red line indicates the presence of fusion evidence; a green line - neighborhood evidence; a blue line – co-occurrence evidence; a purple line - experimental evidence; a yellow line – text mining evidence; a light blue line - database evidence; a black line – co-expression evidence.22 (E). Solution structure of the fragment of human SRY protein (residues 56–131) corresponding to the DNA binding HMG box domain in a complex with its DNA target site in the promoter of the Müllerian substance gene solved by the multidimensional NMR spectroscopy (PDB ID: 1HRZ).40 (F). Aligned PONDR® VSL2 disorder profiles of mouse (black line) and human (red line) SRY proteins. The localization of the HMG box domain of human protein is shown by gray shadow area.

Figure 1B and 1C show that both mouse and human SRYs are predicted to be highly disordered, with mouse protein being essentially more disordered than its human counterpart. Importantly,Figure 1D indicates than mouse SRY is expected to be involved in multiple interactions with various binding partners. All these findings are in a perfect agreement with known facts that transcription factors are highly disordered proteins and often serve as crucial hubs.39

Figure 1E represents a solution structure of the HMG-box domain of human SRY in a complex with its DNA target site in the promoter of the Müllerian substance gene solved by the multidimensional NMR spectroscopy (PDB ID: 1HRZ),40 whereas Figure 1F shows the aligned PONDR® VSL2 disorder profiles of mouse and human SRYs and illustrates that the disorder propensities of their HMG boxes are very similar. Together with high sequence similarity shown in Figure 1A, this finding suggests that the HMG-box of mouse protein should structurally similar to the human protein. Curiously, 3 overlapped dips in Figure 1F (in the vicinity of residues 69, 96, and 118) roughly correspond to the α-helices found in the DNA-bound human protein (residues 66–81, 89–98 and 103–123).

Finally, Table 1 provide a compelling evidence that mouse SRY possesses numerous potential disorder-based binding sites identified by 3 computational tools specialized in finding such sites. Since many of such sites are located within the highly disordered C-tail of this protein, it is tempting to hypothesize that in addition to its known function of a local organizer of chromatin structure mouse SRY can be involved in crucial protein-protein interactions. In agreement with this hypothesis, recent study revealed that a SRY-interacting protein SIP-1/NHERF2 binds to the mouse SRY via a motif located between residues 93 and 103 within the bridge domain of SRY.38 Importantly, this experimentally established motif involved in the interaction with the PDZ1 domain of SIP-1 protein completely coincides with one of the AIBSs (see Table 1), suggesting that other predicted disorder-based binding motifscan be of functional importance too.

Furthermore, based on the observation that a threshold of at least 3 glutamine blocks in the polyQ tract is required for Sry to transactivate Sox9 in a rat pre-Sertoli cell line, it has been suggested that this microsatellite-encoded domain in rodent SRY protein can act as a genetic capacitor to enable the rapid evolution of biological novelty,41 and that unlike human SRY, mouse protein may use its polyQ domain to activate Sox9 transcription.35 Curiously, recent analysis revealed that this polyQ domain is needed to prevent mouse Sry from proteasomal degradation, and provided a direct support to the hypothesis that this domain acts as a TAD enabling direct induction of the Sox9 transcription by rodent SRY protein.35

Tumor suppressor protein 4.1B/DAL-1

Wang et al. represented a comprehensive overview of a membrane skeletal protein 4.1B/DAL-1.42 4.1B/DAL-1 (differentially expressed in adenocarcinoma of the lung protein 1 or type II brain 4.1 protein) is a large (1087 residues) protein that belongs to the protein 4.1 family and links the plasma membrane to the cytoskeleton or associated cytoplasmic signaling effectors thereby facilitating their activities in various pathways. As a result, the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein plays an important role in different mechanisms that modulate cell growth, motility, adhesion, and cytoskeleton organization and also serves as a broad-spectrum tumor suppressor in a variety of cancers.42

This protein is expressed at high levels in brain, but also can be found in kidney, intestine, testis, and lung.43 Although UniProt reports that 4 isoforms are generated by the pre-mRNA alternative splicing, it is also indicated that additional isoforms may exist (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9Y2J2). Therefore, the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein is a typical representative of the 4.1 family, all members of which are characterized by the presence of a variety of tissue- and development-specific protein isoforms generated by alternative splicing and alternative first exons.44-46 One of the characteristic features of the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein is the presence of the FERM (4.1/ezrin/radixin/moesin) domain at its N-terminal part (residues 110–391) together with 2 other conserved structural domains, spectrin/actin-biding domain (SABD, residues 514–654), and C-terminal domain (CTD, residues 861–1087), and 3 unique domains (U1, U2, and U3) that differ 4.1B from other members of the 4.1 family.42 The U1 domain is an N-terminal headpiece (HP, residues 1–109), the U2 domain is situated between the FERM and the SABD (residues 392–513), and the U3 domain (residues 655–860) lies between the SABD and the CTD.

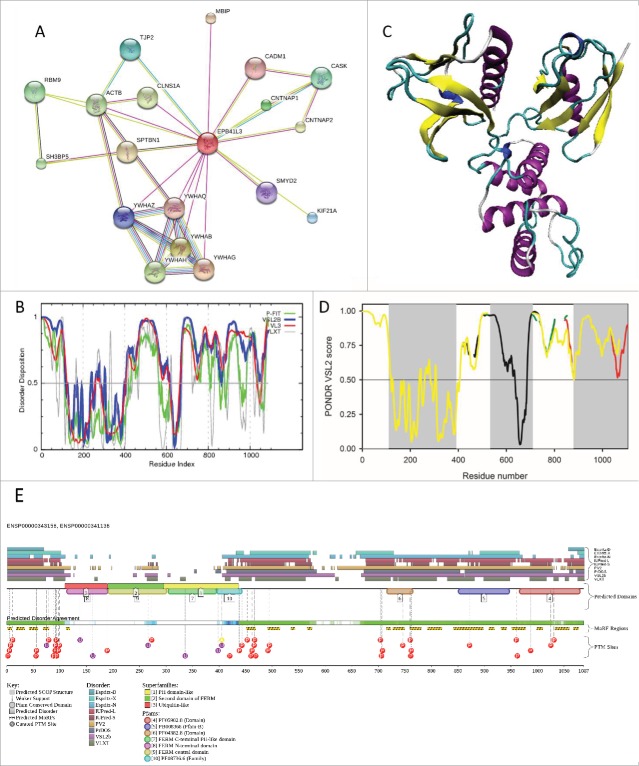

Remarkably, all structural domains of the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein are known to be involved in multiple interactions with various binding partners. For example, the FERM domain is responsible for interaction with tumor suppressor in lung cancer 1 (TSLC-1), cell adhesion molecule 4 (CADM4), protein arginine methyltransferases 3 and 5 (PRMT3 and PRMT5), CD44, Na+ bicarbonate cotransporter 1 (NBC1), membrane palmitoylated proteins 1, 2 and 3 (MPP1, MPP2, and MPP3), chloride channel (pICln), 2 phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), 14–3–3 proteins, contactin-associated proteins Caspr and Caspr2, and paranodin. SABD is obviously involved in interaction with spectrin and actin, whereas CTD is responsible for binding of metabotropic glutamate receptor isoform 8 (mGluR8) and β8-integrin.42 In addition, the 4.1B/DAL-1 can interact with other members of the 4.1 family, merlin and ERM (ezrin/radixin/moesin), and with merlin-interacting βII-spectrin.47 It has been also shown that the residues P353-L390 of the N-terminal FERM domain represent the 14–3–3-binding region of protein 4.1B.48 Figure 2A provides further support for the high interaction potential of the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein by showing the results of the analysis of this protein by STRING.22

Figure 2.

(A). Analysis of the interactivity of the human 4.1B/DAL-1 protein (UniProt ID: Q9Y2J2) by STRING.22 (B). Per-residue disorder distribution in the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein. Disorder propensity was evaluated by a set of predictors from the PONDR family, PONDR® FIT, VSL2B, VL3, and VLXT. Scores above 0.5 correspond to disordered residues/regions. (C). Tertiary structure of the FERM domain (PDB ID: 2HE7; residues 108–390). (D). PONDR VSL2 intrinsic disorder profiles of the alternatively spliced isoforms of the human 4.1B/DAL-1 protein: black line – canonical form (UniProt ID: Q9Y2J2); red line – isoform 2 (UniProt ID: Q9Y2J2–2; differs from the canonical form as follows: 446–446: G → GASVNENHEIYMKDSMSAA; 503–689: missing; 708–719: missing; 784–824: missing); green line – isoform 3 (UniProt ID: Q9Y2J2–3; 446–446: G → GASVNENHEIYMKDSMSAA; 503–689: missing; 708–719: missing; 784–824: missing; 835–1087: missing); yellow line – isoform 4 (UniProt ID: Q9Y2J2–4; 446–446: G → GASVNENHEIYMKDSMSAA; 503–689: missing; 1052–1052: A → E; 1053–1087: missing). The locations of the FERM, SABD and CTD are shown by gray shadow areas. (E). Analysis of disorder propensity and disorder-based functionality of the human 4.1B/DAL-1 protein (UniProt ID: Q9Y2J2) by D2P2 database (http://d2p2.pro/).20

Figure 2B shows that FERM domain represents the mostly structured part of the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein. In agreement with this prediction, Figure 2C represents a crystal structure of the FERM domain and shows that it consists of 3 independently-folded subdomains. Curiously, although FERM is an ordered domain, there is a very strong probability that at least some of its interacting partners are disordered or contain disordered binding motifs that undergo binding induced folding. In other words, it is likely that at least some partners of the FERM domain possess molecular recognition features (MoRFs); i.e., short order-prone motifs that are located within a long disordered region and are able to undergo disorder-to-order transition during the binding to a specific partner. Structure of the complex between the FERM domain of the human 4.1B/DAL-1 protein and a short binding fragment of the TSLC1 cytoplasmic domain (residues 400–411, UniProt ID: Q9BY67) is in agreement with this hypothesis,49 since this structure can be described as a MoRF-based complex, where a short β-MoRF of the TSLC1 interacts with a well-defined hydrophobic pocket in the structural C-lobe of the FERM domain (PDB ID: 3BIN). Importantly, this binding motif is located within the C-terminal tail of TSLC1, which is predicted to be disordered. Furthermore, according to the MobiDB database (http://mobidb.bio.unipd.it/),12,13 some of the STRING identified binding partners of 4.1B/DAL-1 protein are predicted to contain substantial amount of intrinsic disorder. For example, proteins CNTNAP2 (UniProt ID: Q75MA1), β-spectrin (UniProt ID: B4DIF8), protein similar to tight junction protein ZO-2 (UniProt ID: B7Z954), PRO1478 (UniProt ID: Q9P1H0), tight junction protein ZO-2 (UniProt ID: Q9UDY2), similar to tight junction protein 2 (TJP2, UniProt ID: B7Z2R3), and tight junction protein ZO-2 (UniProt ID: B1AN86) are predicted to have 52.4, 45.5, 41.1, 35.4, 34.8, 27.7, and 19.25 % disordered residues, respectively.

Table 1 together with Figures 2B, 2D, and 2E provide further support for the abundance and functional importance of intrinsic disorder in the human 4.1B/DAL-1 protein. In fact, these data show that 4.1B contains several long disordered regions, which are enriched in potential disorder-based binding motifs (Table 1,Figure 2E) and numerous sites of posttranslational modifications, PTMs (Figure 2E). The fact that disordered domains/regions of the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein are densely populated with the phosphorylation sites (see Figure 2E) is in agreement with the well-known notion that phosphorylation50 and many other enzymatically catalyzed PTMs are preferentially located within the IDPRs.51 Another important observation related to the functionally important disordered regions in the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein is the fact that this protein has numerous isoforms produced by alternative splicing. Earlier studies revealed that polypeptide segments affected by alternative splicing are often intrinsically disordered thereby enabling alternative splicing-mediated functional and regulatory diversification of affected proteins while avoiding potential structural complications.52 In agreement with these observations, Figure 2D represents PONDR VSL2 disorder profiles of 4 isoforms of this protein and clearly shows that alternative splicing events mostly affect IDPRs of the 4.1B/DAL-1 protein.

Regulation of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) by cyclin-A2

Bendris et al. analyzed a novel role of cyclin-A2 (Ccna2) in regulation of an epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) associated with loss of cell-to-cell contacts.53 Typically, while considering the link of Ccn2 to cancer, its role in controlling cell proliferation is taken as a major culprit. However, it has been established that in several types of cancer (e.g., renal, colorectal, ovarian, and prostate carcinomas, and oral squamous cell carcinoma), low levels of this protein were associated with more aggressive and invasive forms of tumor,54-58 suggesting some novel roles of Ccna2 in carcinogenesis.58 To delve into this novel tumorigenetic activity of Ccna2, Bendris et al. looked at functions of this protein in an epithelial context, paying special attention to the role of inactivation of Ccna2 in the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT).53 They established that Ccna2-depleted cells showed increased 3D invasive properties, increased formation of tumorospheres, and enhanced invasion. Furthermore, Ccna2 depletion in the mouse mammary gland epithelial cell line NmuMG was correlated with the expression of stem cell markers, suggesting that loss of Cyclin A2 may be related to the initiation of the cancer stem cell capabilities.53

These findings of novel roles of Ccna2 in EMT regulation represents an important addition to the known functions of this protein in regulation of the somatic cell cycle, where it is essential for at least 2 critical points, during the S phase, when it activates cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2), and during the G2 to M transition when it activates CDK1.59-61 Ccna2 and other cyclins are known to play a major role in the substrate recognition by the cyclin-CDK complexes.62,63 Curiously, both CDKs and cyclins are promiscuous binders where a single CDK can interact with various cyclins and a single cyclin can interact with various CDKs.64

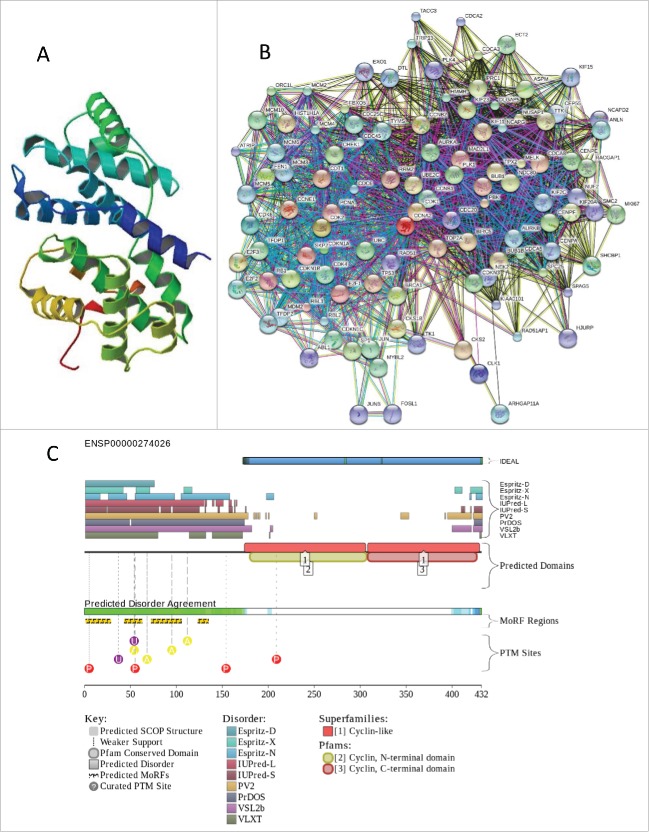

It has been emphasized that, structurally, Ccna2 is characterized by a rigid globular structure, except for its N-terminal part. The globular part of the protein is comprised of 2 sub domains: the N-terminal cyclin box (residues 175–306), conserved among cyclins, and the C-terminal cyclin box fold (CBF, residues 308–430). They both consist of 5 α-helices, and an additional α-helix was found in the N-terminal half of the protein.65Figure 3A represents the tertiary structure of the globular domain of the human Ccna2 (residues 175–432; PDB ID: 1VIN). This globular domain plays an important part in the cyclin-CDF complex formation, where the hydrophobic region (MRAIL motif) of the first α-helix within the N-terminal cyclin box is engaged in interaction with the PSTAIRE motif in the N-terminal lobe of the CDK.66 The aforementioned N-terminal α-helix (residues 176–201 in human protein, ref.67) is considered as an independent structural unit that contribute to the binding of Ccna2 to CDKs68 and is believed to be crucial for the binding specificity of the cyclin-CDK complexes.67

Figure 3.

(A). Crystal structure of the C-terminal half of human cyclin A2 (residues 175–432, PDB ID: 1VIN). (B). Analysis of the interactivity of the human cyclin A2 (UniProt ID: P20248) by STRING.22 (C). Evaluation of the functional intrinsic disorder propensity of the cyclin A2 (UniProt ID: P20248) by D2P2 database (http://d2p2.pro/).20

In addition to CDK1 and CDK2, Ccna2 was shown to interact with p21, p27, and p107,65 as well as with more than 230 other proteins (BioGrid: http://thebiogrid.org/107331). Figure 3B illustrates this fact by showing Ccna2 at the center of a very large protein-protein interaction network generated by STRING.22 Table 1 and Figure 3C shows that the N-terminal tail of human Ccna2 (residues 1–181) is predicted to be highly disordered, contains numerous PTM sites and possesses several disorder-based protein interaction motifs. It is very likely that this disordered nature of the N-tail defines the binding promiscuity of human Ccna2.

Heteromerization and cross-regulation of the channel kinases TRPM6 and TRPM7

Brandao et al. studied cross regulation of 2 important members of the transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) subfamily of cationic ion channels, TRPM6 and TRPM7, which are Ca2+ and Mg2+ permeable ion channels implicated in regulating Mg2+ levels in various cellular contexts.69 Curiously, these channels are functionally non-redundant and neither can compensate for the other's deficiency.70-76 Furthermore, they are clearly involved in important functional cross-talk, since TRPM7 was shown to facilitate TRPM6 plasma membrane localization and since TRPM6 kinase is able to phosphorylate serine residues of TRPM7.73

An important feature of TRPM6 and TRPM7 is their Janus protein kinase-ion channel functionality. In fact, these 2 proteins are the only known fusions between a serine/threonine kinase domain and an ion pore. Kinase domains of these proteins belong to the atypical α kinase family, share 75% sequence identity, and are localized at the cytosolic C-terminus of the ion channels.69,77 Crystal structure of the kinase domain of mouse TRPM7 (UniProt ID: Q923J1) has been solved (e.g.,, PDB ID: 1IA9) and analysis of this structure revealed a striking similarity to eukaryotic protein kinases in the catalytic core (despite the lack of detectable sequence similarity to classical eukaryotic protein kinases) and to metabolic enzymes with ATP-grasp domains.78

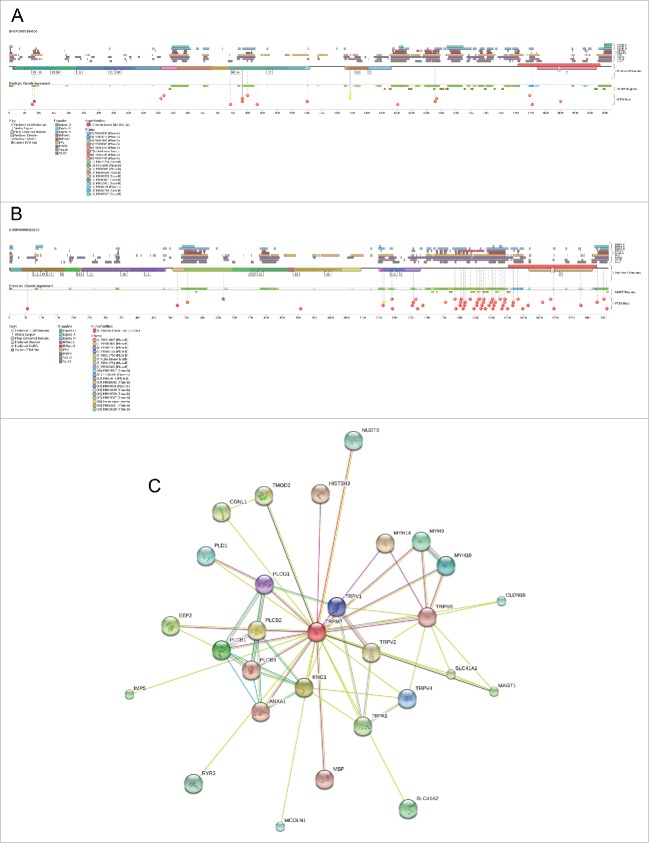

Being ion channels, TRPM6 and TRPM7 are transmembrane proteins with 7 transmembrane helices (residues 742–762, 842–862, 906–926, 940–960, 973–993, 1013–1033, and 1048–1068 in TRPM6 and residues 756–776, 856–876, 919–939, 963–983, 996–1016, 1036–1056, and 1075–1095 in TRPM7). These transmembrane helices are connected by loops ranging in length from ∼10 to ∼80 residues. Both proteins contain long N- and C-terminal cytoplasmic domains (residues 1–741 and 1069–2022 in TRPM6, and residues 1–755 and 1095–1863 in TRPM7). C-terminal tails include kinase domains (residues 1750–1980 and 1592–1822 in TRPM6 and TRPM7, respectively). Table 1 and Figure 4A and 4B show that the N-terminal halves of both proteins are predicted to be mostly disordered except to 2 relatively long disordered regions in the vicinity of residues 540 and 800, whereas except to the kinase domains, the C-terminal halves are predicted to be highly disordered. As with many other transmembrane proteins,79-84 most of the TRPM6 and TRPM7 disordered regions are located inside the cell (see Table 1, where the corresponding residue ranges are shown in bold font). Table 1 and Figure 4A and 4B also illustrates that the PTM sites and the disorder-based sites of protein-protein interactions are predominantly located within the cytoplasmic disordered regions. These observations suggest that the modifiable and pliable cytoplasmic IDPRs are needed for the TRPM6 and TRPM7, which are known to have a rather well-developed protein-protein interaction network with several joint interactors (see Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

(A). Evaluation of the functional intrinsic disorder propensity of the human TRPM6 (UniProt ID: Q9BX84) by D2P2 database (http://d2p2.pro/).20 (B). Evaluation of the functional intrinsic disorder propensity of TRPM7 (UniProt ID: Q96QT4) by D2P2 database (http://d2p2.pro/).20 (C). Analysis of the interactivity of the human TRPM6 (UniProt ID: Q9BX84) and TRPM7 (UniProt ID: Q96QT4) by STRING.22

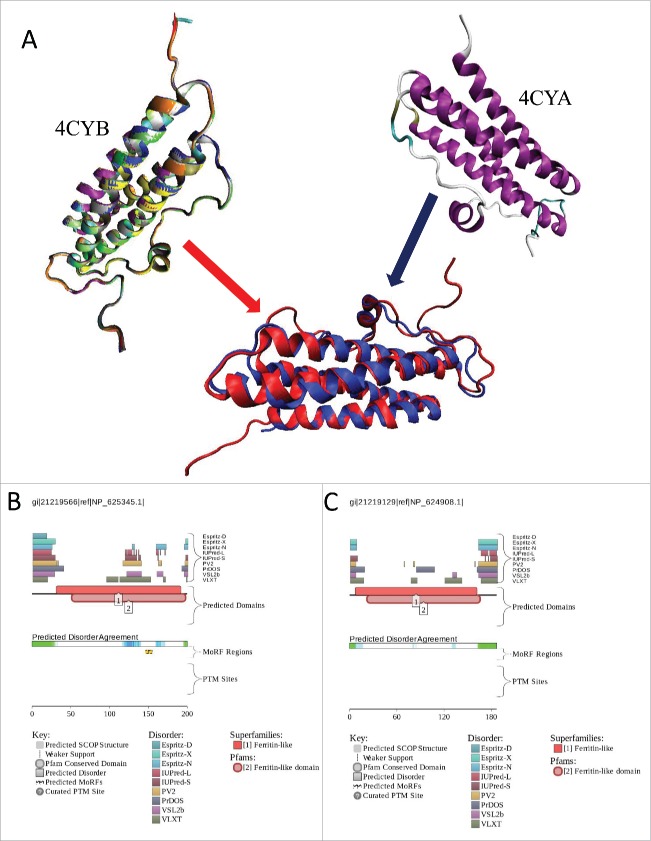

Roles of tails in the biochemical properties of 2 Dps proteins from Streptomyces coelicolor

Hitchings et al. presented functional and structural analysis of 2 members of the DNA protection proteins from starved cells (Dps) protein subfamily, proteins DpsC and DpsA from Streptomyces coelicolor.85 Since the fact that the 27 residues of the N-terminal region of DpsC were disordered in crystal structure of this protein was mentioned in this study (once), and since this paper is dedicated to the analysis of the roles of “tails” in functions of DpsC and DpsA, functional disorder in these from Streptomyces coelicolor is not completely missed. However, disorder was obviously overlooked there.

Dps is a subfamily of a large superfamily of iron-related proteins that are fundamental to the metabolism, control and homeostasis of cellular iron. In addition to various Dps proteins, this superfamily includes classical ferritins (Ftn) and the haem-binding bacterioferritins (Bfr).85 Structurally and functionally, monomeric Dps proteins are similar to Ftns and possess the archetypal ferritin-like structure composed of 4-helix bundle (A, B, C and D helices) and an additional short helix (BC). It was pointed out that in this structure, the N- and Citermini are placed at opposing ends of the bundle, and the fully folded helix pairs (A + B and C + D) remain anti-parallel due to the specific “up-down-down-up” arrangement of this 4-helix bundle.86,87 Figure 5A shows crystal structures of the DpsC and DpsA proteins from Streptomyces coelicolor and illustrates this specific topology, where the BC helix is located within a very long loop and is positioned centrally and orthogonally to the 4-helix bundle. Figure 4A shows that the subunits of the Streptomyces coelicolor DpsC dodecamer are structurally almost identical, possessing slight heterogeneity at their tails. It is also seen that DpsC and DpsA are structurally superimposable, possessing RMSD of 1.25 Å when structurally aligned at 150 residues. Again, largest structural deviations are seen in the terminal regions and in the loops connecting the BC helix to the remaining 4-helix bundle.

Figure 5.

(A). Structural analysis of DpsC (PDB ID: 4CYB, residues 28–200) and DpsA (PDB ID: 4CYA, residues 4–163) Dps proteins from Streptomyces coelicolor. Since structural information on 12 chains constituting the DpsC dodecamer is available, the shown plot represents the results of structural alignment of these monomers using the MultiProt algorithm,107 where structures of different monomers are shown by different color. The MultiProt algorithm107 was also used to structurally align DpsC (shown as a red structure in the aligned plot) and DpsA (shown as a blue structure). (B). Evaluation of the functional intrinsic disorder propensity of DspC (UniProt ID: Q9K3L0) by D2P2 database (http://d2p2.pro/).20 (C). Evaluation of the functional intrinsic disorder propensity of DspA (UniProt ID: Q9R408) by D2P2 database (http://d2p2.pro/).20

Dps proteins assemble to the dodecameric nanocages,86 in which each subunit interfaces with 5 other subunits.86,87 It was also pointed out that most Dps proteins possess poorly conserved terminal extensions or N- and C-tails that extend from the 4-helix bundle, protruding from the surface of the dodecameric cage, and playing different functional roles in Dps proteins from various species.85 Functional repertoire of these tails ranges from participation in the oligomeric assembly to DNA binding, to involvement in the dodecamer stabilization, to playing a role in ferroxidase activity and the ferric oxide deposition.85

In the Streptomyces coelicolor DpsA protein (which is 187 residues long), the N-terminal tail is 15 amino acids long whereas the C-terminal tail consists of the 25 residues. In the crystal structure of this protein, the resolved N- and C-tails contain 12 and 9 residues, respectively.85 There are 18 residues from the C-terminal tail missing from the crystallographic model, with 3 amino acid residues missing from the N-terminal tail.85 In the Streptomyces coelicolor DpsC protein (which is 200 residues long), the N-terminal tail is 45 amino acids long whereas the C-terminal tail consists of the 8 residues. In the DpsC crystal structure, only 17 amino acids from the N-tail were visible in the electron density map, with the other 27 amino acids being disordered, whereas 7 of the 8 residues were resolved in the C-tail.85 In agreement with these observations, Table 1 and Figure 5B and 5C shows that the N- and C-terminal regions of the Streptomyces coelicolor DpsC and DspA proteins are predicted to be disordered. Importantly, it was emphasized that the propensity for intrinsic disorder is unevenly distributed within proteins, being typically more common at protein termini.88 Disordered tails are known to be engaged in a wide range of important functions, some of which are unique for termini and cannot be found in other disordered parts of a protein.88 Some of the interesting examples of the functionally unique disordered termini are histone tails,89-102 termini of ribosomal proteins,103 C-tail of the canonical PTEN,104 and N-tail of the PTEN-long.105

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from Russian Science Foundation RSCF No. 14-24-00131.

References

- 1. Uversky VN. Digested disorder: quarterly intrinsic disorder digest (january/february/ march, 2013). Intrinsically Disordered Proteins 2013; 1:e25496; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/idp.25496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeForte S, Reddy KD, Uversky VN. Digested disorder, issue #2: quarterly intrinsic disorder digest (april/may/june, 2013). Intrinsically Disordered Proteins 2013; 1:e27454; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/idp.27454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reddy KD, DeForte S, Uversky VN. Digested disorder, issue #3: quarterly intrinsic disorder digest (july-august-september, 2013). Intrinsically Disordered Proteins 2014; 2:e27833; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/idp.27833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uversky VN. Unreported intrinsic disorder in proteins: building connections to the literature on IDPs. Intrinsically Disordered Proteins 2014; 2:e36409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Obradovic Z, Peng K, Vucetic S, Radivojac P, Dunker AK. Exploiting heterogeneous sequence properties improves prediction of protein disorder. Proteins 2005; 61 7:176-82; PMID:16187360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/prot.20735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peng ZL, Kurgan L. Comprehensive comparative assessment of in-silico predictors of disordered regions. Curr Protein Pept Sci 2012; 13:6-18; PMID:22044149; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2174/138920312799277938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fan X, Kurgan L. Accurate prediction of disorder in protein chains with a comprehensive and empirically designed consensus. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2014; 32:448-64; PMID:23534882; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/07391102.2013.775969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Obradovic Z, Peng K, Vucetic S, Radivojac P, Brown CJ, Dunker AK. Predicting intrinsic disorder from amino acid sequence. Proteins 2003; 53 6:566-72; PMID:14579347; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/prot.10532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Romero P, Obradovic Z, Li X, Garner EC, Brown CJ, Dunker AK. Sequence complexity of disordered protein. Proteins 2001; 42:38-48; PMID:11093259; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/1097-0134(20010101)42:1%3c38::AID-PROT50%3e3.0.CO;2-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Xue B, Dunbrack RL, Williams RW, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. PONDR-FIT: a meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta 2010; 1804:996-1010; PMID:20100603; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones DT, Cozzetto D. DISOPRED3: Precise disordered region predictions with annotated protein binding activity. Bioinformatics 2014; PMID:25391399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Di Domenico T, Walsh I, Martin AJ, Tosatto SC. MobiDB: a comprehensive database of intrinsic protein disorder annotations. Bioinformatics 2012; 28:2080-1; PMID:22661649; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Potenza E, Domenico TD, Walsh I, Tosatto SC. MobiDB 2.0: an improved database of intrinsically disordered and mobile proteins. Nucleic Acid Res 2015; 43:D315-20; PMID:25361972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Walsh I, Martin AJ, Di Domenico T, Tosatto SC. ESpritz: accurate and fast prediction of protein disorder. Bioinformatics 2012; 28:503-9; PMID:22190692; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics 2005; 21:3433-4; PMID:15955779; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Linding R, Jensen LJ, Diella F, Bork P, Gibson TJ, Russell RB. Protein disorder prediction: implications for structural proteomics. Structure 2003; 11:1453-9; PMID:14604535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.str.2003.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Linding R, Russell RB, Neduva V, Gibson TJ. GlobPlot: exploring protein sequences for globularity and disorder. Nucleic Acid Res 2003; 31:3701-8; PMID:12824398; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkg519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peng K, Radivojac P, Vucetic S, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z. Length-dependent prediction of protein intrinsic disorder. Bmc Bioinformatics 2006; 7:218; PMID:16618368; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1471-2105-7-208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang ZR, Thomson R, McNeil P, Esnouf RM. RONN: the bio-basis function neural network technique applied to the detection of natively disordered regions in proteins. Bioinformatics 2005; 21:3369-76; PMID:15947016; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Oates ME, Romero P, Ishida T, Ghalwash M, Mizianty MJ, Xue B, Dosztanyi Z, Uversky VN, Obradovic Z, Kurgan L, et al. D(2)P(2): database of disordered protein predictions. Nucleic Acid Res 2013; 41:D508-16; PMID:23203878; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gks1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ishida T, Kinoshita K. PrDOS: prediction of disordered protein regions from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acid Res 2007; 35:W460-4; PMID:17567614; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkm363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Minguez P, Doerks T, Stark M, Muller J, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acid Res 2011; 39:D561-8; PMID:21045058; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkq973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Oldfield CJ, Cheng Y, Cortese MS, Romero P, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Coupled folding and binding with α-helix-forming molecular recognition elements. Biochemistry 2005; 44:12454-70; PMID:16156658; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi050736e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cheng Y, Oldfield CJ, Meng J, Romero P, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Mining α-helix-forming molecular recognition features with cross species sequence alignments. Biochemistry 2007; 46:13468-77; PMID:17973494; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi7012273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Disfani FM, Hsu WL, Mizianty MJ, Oldfield CJ, Xue B, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, Kurgan L. MoRFpred, a computational tool for sequence-based prediction and characterization of short disorder-to-order transitioning binding regions in proteins. Bioinformatics 2012; 28:i75-83; PMID:22689782; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meszaros B, Simon I, Dosztanyi Z. Prediction of protein binding regions in disordered proteins. PLoS Comput Biol 2009; 5:e1000376; PMID:19412530; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dosztanyi Z, Meszaros B, Simon I. ANCHOR: web server for predicting protein binding regions in disordered proteins. Bioinformatics 2009; 25:2745-6; PMID:19717576; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. The pairwise energy content estimated from amino acid composition discriminates between folded and intrinsically unstructured proteins. J Mol Biol 2005; 347:827-39; PMID:15769473; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tanaka SS, Nishinakamura R. Regulation of male sex determination: genital ridge formation and sry activation in mice. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71:4781-802; PMID:25139092; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-014-1703-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gubbay J, Collignon J, Koopman P, Capel B, Economou A, Munsterberg A, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. A gene mapping to the sex-determining region of the mouse Y chromosome is a member of a novel family of embryonically expressed genes. Nature 1990; 346:245-50; PMID:2374589; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/346245a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sinclair AH, Berta P, Palmer MS, Hawkins JR, Griffiths BL, Smith MJ, Foster JW, Frischauf AM, Lovell-Badge R, Goodfellow PN. A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature 1990; 346:240-4; PMID:1695712; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/346240a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koopman P, Gubbay J, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R. Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for sry. Nature 1991; 351:117-21; PMID:2030730; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/351117a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Svingen T, Koopman P. Building the mammalian testis: origins, differentiation, and assembly of the component cell populations. Genes Dev 2013; 27:2409-26; PMID:24240231; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.228080.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harley VR, Goodfellow PN. The biochemical role of SRY in sex determination. Mol Reprod Dev 1994; 39:184-93; PMID:7826621; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/mrd.1080390211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhao L, Ng ET, Davidson TL, Longmuss E, Urschitz J, Elston M, Moisyadi S, Bowles J, Koopman P. Structure-function analysis of mouse sry reveals dual essential roles of the C-terminal polyglutamine tract in sex determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U SA 2014; 111:11768-73; PMID:25074915; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1400666111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weiss MA. Floppy SOX: mutual induced fit in hmg (high-mobility group) box-DNA recognition. Mol Endocrinol 2001; 15:353-62; PMID:11222737; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1210/mend.15.3.0617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Coward P, Nagai K, Chen D, Thomas HD, Nagamine CM, Lau YF. Polymorphism of a CAG trinucleotide repeat within sry correlates with B6.YDom sex reversal. Nat Gen 1994; 6:245-50; PMID:8012385; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng0394-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thevenet L, Albrecht KH, Malki S, Berta P, Boizet-Bonhoure B, Poulat F. NHERF2/SIP-1 interacts with mouse SRY via a different mechanism than human SRY. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:38625-30; PMID:16166090; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M504127200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu J, Perumal NB, Oldfield CJ, Su EW, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Intrinsic disorder in transcription factors. Biochemistry 2006; 45:6873-88; PMID:16734424; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi0602718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Werner MH, Huth JR, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Molecular basis of human 46X,Y sex reversal revealed from the three-dimensional solution structure of the human SRY-DNA complex. Cell 1995; 81:705-14; PMID:7774012; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90532-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chen YS, Racca JD, Sequeira PW, Phillips NB, Weiss MA. Microsatellite-encoded domain in rodent sry functions as a genetic capacitor to enable the rapid evolution of biological novelty. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:E3061-70; PMID:23901118; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1300860110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang Z, Zhang J, Ye M, Zhu M, Zhang B, Roy M, Liu J, An X. Tumor suppressor role of protein 4.1B/DAL-1. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71:4815-30; PMID:25183197; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-014-1707-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tran YK, Bogler O, Gorse KM, Wieland I, Green MR, Newsham IF. A novel member of the NF2/ERM/4.1 superfamily with growth suppressing properties in lung cancer. Cancer Res 1999; 59:35-43; PMID:9892180 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Conboy JG, Chan J, Mohandas N, Kan YW. Multiple protein 4.1 isoforms produced by alternative splicing in human erythroid cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 1988; 85:9062-5; PMID:3194408; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Conboy JG, Chan JY, Chasis JA, Kan YW, Mohandas N. Tissue- and development-specific alternative RNA splicing regulates expression of multiple isoforms of erythroid membrane protein 4.1. J Biol Chem 1991; 266:8273-80; PMID:2022644 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tan JS, Mohandas N, Conboy JG. Evolutionarily conserved coupling of transcription and alternative splicing in the EPB41 (protein 4.1R) and EPB41L3 (protein 4.1B) genes. Genomics 2005; 86:701-7; PMID:16242908; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gutmann DH, Hirbe AC, Huang ZY, Haipek CA. The protein 4.1 tumor suppressor, DAL-1, impairs cell motility, but regulates proliferation in a cell-type-specific fashion. Neurobiol Dis 2001; 8:266-78; PMID:11300722; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/nbdi.2000.0376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yu T, Robb VA, Singh V, Gutmann DH, Newsham IF. The 4.1/ezrin/radixin/moesin domain of the DAL-1/Protein 4.1B tumour suppressor interacts with 14-3-3 proteins. Biochemical J 2002; 365:783-9; PMID:11996670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Busam RD, Thorsell AG, Flores A, Hammarstrom M, Persson C, Obrink B, Hallberg BM. Structural basis of tumor suppressor in lung cancer 1 (TSLC1) binding to differentially expressed in adenocarcinoma of the lung (DAL-1/4.1B). J Biol Chem 2011; 286:4511-6; PMID:21131357; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M110.174011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Iakoucheva LM, Radivojac P, Brown CJ, O'Connor TR, Sikes JG, Obradovic Z, Dunker AK. The importance of intrinsic disorder for protein phosphorylation. Nucleic Acid Res 2004; 32:1037-49; PMID:14960716; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/gkh253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pejaver V, Hsu WL, Xin F, Dunker AK, Uversky VN, Radivojac P. The structural and functional signatures of proteins that undergo multiple events of post-translational modification. Protein Sci 2014; 23:1077-93; PMID:24888500; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/pro.2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Romero PR, Zaidi S, Fang YY, Uversky VN, Radivojac P, Oldfield CJ, Cortese MS, Sickmeier M, LeGall T, Obradovic Z, et al. Alternative splicing in concert with protein intrinsic disorder enables increased functional diversity in multicellular organisms. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103:8390-5; PMID:16717195; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0507916103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bendris N, Cheung CT, Leong HS, Lewis JD, Chambers AF, Blanchard JM, Lemmers B. Cyclin A2, a novel regulator of EMT. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71:4881-94; PMID:24879294; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-014-1654-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Li JQ, Miki H, Wu F, Saoo K, Nishioka M, Ohmori M, Imaida K. Cyclin A correlates with carcinogenesis and metastasis, and p27(kip1) correlates with lymphatic invasion, in colorectal neoplasms. Hum Pathol 2002; 33:1006-15; PMID:12395374; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1053/hupa.2002.125774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Aaltomaa S, Lipponen P, Ala-Opas M, Eskelinen M, Syrjanen K, Kosma VM. Expression of cyclins A and D and p21(waf1/cip1) proteins in renal cell cancer and their relation to clinicopathological variables and patient survival. British J Cancer 1999; 80:2001-7; PMID:10471053; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Davidson B, Risberg B, Berner A, Nesland JM, Trope CG, Kristensen GB, Bryne M, Goscinski M, van de Putte G, Florenes VA. Expression of cell cycle proteins in ovarian carcinoma cells in serous effusions-biological and prognostic implications. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 83:249-56; PMID:11606079; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/gyno.2001.6388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wang YF, Chen JY, Chang SY, Chiu JH, Li WY, Chu PY, Tai SK, Wang LS. Nm23-H1 expression of metastatic tumors in the lymph nodes is a prognostic indicator of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2008; 122:377-86; PMID:17918157; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.23096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Arsic N, Bendris N, Peter M, Begon-Pescia C, Rebouissou C, Gadea G, Bouquier N, Bibeau F, Lemmers B, Blanchard JM. A novel function for cyclin A2: control of cell invasion via RhoA signaling. J Cell Biol 2012; 196:147-62; PMID:22232705; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.201102085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nigg EA. Cyclin-dependent protein kinases: key regulators of the eukaryotic cell cycle. BioEssays 1995; 17:471-80; PMID:7575488; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bies.950170603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Morgan DO. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 1997; 13:261-91; PMID:9442875; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Yam CH, Fung TK, Poon RY. Cyclin A in cell cycle control and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 2002; 59:1317-26; PMID:12363035; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-002-8510-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cross FR, Yuste-Rojas M, Gray S, Jacobson MD. Specialization and targeting of B-type cyclins. Mol Cell 1999; 4:11-9; PMID:10445023; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80183-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Roberts JM. Evolving ideas about cyclins. Cell 1999; 98:129-32; PMID:10428024; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81007-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Peeper DS, Parker LL, Ewen ME, Toebes M, Hall FL, Xu M, Zantema A, van der Eb AJ, Piwnica-Worms H. A- and B-type cyclins differentially modulate substrate specificity of cyclin-cdk complexes. EMBO J 1993; 12:1947-54; PMID:8491188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bendris N, Lemmers B, Blanchard JM, Arsic N. Cyclin A2 mutagenesis analysis: a new insight into CDK activation and cellular localization requirements. PloS one 2011; 6:e22879; PMID:21829545; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0022879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Endicott JA, Noble ME, Tucker JA. Cyclin-dependent kinases: inhibition and substrate recognition. Curr Opin Structural Biol 1999; 9:738-44; PMID:10607671; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)00038-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Goda T, Funakoshi M, Suhara H, Nishimoto T, Kobayashi H. The N-terminal helix of Xenopus cyclins A and B contributes to binding specificity of the cyclin-CDK complex. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:15415-22; PMID:11278837; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M011101200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fan JS, Cheng HC, Zhang M. A peptide corresponding to residues asp177 to asn208 of human cyclin a forms an α-helix. Bio Biophysical Res Commun 1998; 253:621-7; PMID:9918778; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Brandao K, Deason-Towne F, Zhao X, Perraud AL, Schmitz C. TRPM6 kinase activity regulates TRPM7 trafficking and inhibits cellular growth under hypomagnesic conditions. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71:4853-67; PMID:24858416; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-014-1647-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Schlingmann KP, Weber S, Peters M, Niemann Nejsum L, Vitzthum H, Klingel K, Kratz M, Haddad E, Ristoff E, Dinour D, et al. Hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia is caused by mutations in TRPM6, a new member of the TRPM gene family. Nat Gen 2002; 31:166-70; PMID:12032568; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Walder RY, Landau D, Meyer P, Shalev H, Tsolia M, Borochowitz Z, Boettger MB, Beck GE, Englehardt RK, Carmi R, et al. Mutation of TRPM6 causes familial hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia. Nat Gen 2002; 31:171-4; PMID:12032570; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ng901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schmitz C, Perraud AL, Johnson CO, Inabe K, Smith MK, Penner R, Kurosaki T, Fleig A, Scharenberg AM. Regulation of vertebrate cellular Mg2+ homeostasis by TRPM7. Cell 2003; 114:191-200; PMID:12887921; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00556-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Schmitz C, Dorovkov MV, Zhao X, Davenport BJ, Ryazanov AG, Perraud AL. The channel kinases TRPM6 and TRPM7 are functionally nonredundant. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:37763-71; PMID:16150690; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M509175200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Jin J, Desai BN, Navarro B, Donovan A, Andrews NC, Clapham DE. Deletion of Trpm7 disrupts embryonic development and thymopoiesis without altering Mg2+ homeostasis. Science 2008; 322:756-60; PMID:18974357; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.1163493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Ryazanova LV, Rondon LJ, Zierler S, Hu Z, Galli J, Yamaguchi TP, Mazur A, Fleig A, Ryazanov AG. TRPM7 is essential for Mg(2+) homeostasis in mammals. Nat Commun 2010; 1:109; PMID:21045827; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/ncomms1108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Woudenberg-Vrenken TE, Sukinta A, van der Kemp AW, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Transient receptor potential melastatin 6 knockout mice are lethal whereas heterozygous deletion results in mild hypomagnesemia. Nephron Physiol 2011; 117:p11-9; PMID:20814221; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000320580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ryazanova LV, Dorovkov MV, Ansari A, Ryazanov AG. Characterization of the protein kinase activity of TRPM7/ChaK1, a protein kinase fused to the transient receptor potential ion channel. J Biol Chem 2004; 279:3708-16; PMID:14594813; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M308820200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yamaguchi H, Matsushita M, Nairn AC, Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the atypical protein kinase domain of a TRP channel with phosphotransferase activity. Mol Cell 2001; 7:1047-57; PMID:11389851; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00256-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Sigalov AB, Aivazian DA, Uversky VN, Stern LJ. Lipid-binding activity of intrinsically unstructured cytoplasmic domains of multichain immune recognition receptor signaling subunits. Biochem 2006; 45:15731-9; PMID:17176095; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi061108f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Minezaki Y, Homma K, Nishikawa K. Intrinsically disordered regions of human plasma membrane proteins preferentially occur in the cytoplasmic segment. J Mol Biol 2007; 368:902-13; PMID:17368479; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. De Biasio A, Guarnaccia C, Popovic M, Uversky VN, Pintar A, Pongor S. Prevalence of intrinsic disorder in the intracellular region of human single-pass type I proteins: the case of the notch ligand Delta-4. J Proteome Res 2008; 7:2496-506; PMID:18435556; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/pr800063u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Xue B, Li L, Meroueh SO, Uversky VN, Dunker AK. Analysis of structured and intrinsically disordered regions of transmembrane proteins. Mol BioSystems 2009; 5:1688-702; PMID:19585006; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1039/b905913j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sigalov AB, Uversky VN. Differential occurrence of protein intrinsic disorder in the cytoplasmic signaling domains of cell receptors. Self/nonself 2011; 2:55-72; PMID:21776336; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/self.2.1.14790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tipparaju SM, Li XP, Kilfoil PJ, Xue B, Uversky VN, Bhatnagar A, Barski OA. Interactions between the C-terminus of Kv1.5 and Kvbeta regulate pyridine nucleotide-dependent changes in channel gating. Pflugers Arch 2012; 463:799-818; PMID:22426702; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00424-012-1093-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hitchings MD, Townsend P, Pohl E, Facey PD, Jones DH, Dyson PJ, Del Sol R. A tale of tails: deciphering the contribution of terminal tails to the biochemical properties of two dps proteins from streptomyces coelicolor. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71:4911-26; PMID:24915944; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-014-1658-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Grant RA, Filman DJ, Finkel SE, Kolter R, Hogle JM. The crystal structure of dps, a ferritin homolog that binds and protects DNA. Nat Struct Biol 1998; 5:294-303; PMID:9546221; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nsb0498-294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gauss GH, Benas P, Wiedenheft B, Young M, Douglas T, Lawrence CM. Structure of the DPS-like protein from sulfolobus solfataricus reveals a bacterioferritin-like dimetal binding site within a DPS-like dodecameric assembly. Biochem 2006; 45:10815-27; PMID:16953567; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi060782u [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Uversky VN. The most important thing is the tail: multitudinous functionalities of intrinsically disordered protein termini. FEBS Lett 2013; 587:1891-901; PMID:23665034; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ausio J, Abbott DW. The many tales of a tail: carboxyl-terminal tail heterogeneity specializes histone H2A variants for defined chromatin function. Biochem 2002; 41:5945-9; PMID:11993987; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/bi020059d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Zheng C, Hayes JJ. Structures and interactions of the core histone tail domains. Biopolymers 2003; 68:539-46; PMID:12666178; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/bip.10303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Lu X, Hansen JC. Revisiting the structure and functions of the linker histone C-terminal tail domain. Biochem Cell Biol 2003; 81:173-6; PMID:12897851; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1139/o03-041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Hansen JC, Lu X, Ross ED, Woody RW. Intrinsic protein disorder, amino acid composition, and histone terminal domains. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:1853-6; PMID:16301309; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.R500022200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Chambers AL, Downs JA. The contribution of the budding yeast histone H2A C-terminal tail to DNA-damage responses. Biochem Society Trans 2007; 35:1519-24; PMID:18031258; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/BST0351519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hadnagy A, Beaulieu R, Balicki D. Histone tail modifications and noncanonical functions of histones: perspectives in cancer epigenetics. Mol Cancer Ther 2008; 7:740-8; PMID:18413789; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Misri S, Pandita S, Kumar R, Pandita TK. Telomeres, histone code, and DNA damage response. Cytogen Gen Res 2008; 122:297-307; PMID:19188699; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1159/000167816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Munshi A, Shafi G, Aliya N, Jyothy A. Histone modifications dictate specific biological readouts. J Genetics Genomics 2009; 36:75-88; PMID:19232306; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1673-8527(08)60094-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Billur M, Bartunik HD, Singh PB. The essential function of HP1 β: a case of the tail wagging the dog? Trend Biochem Sci 2010; 35:115-23; PMID:19836960; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Peng Z, Mizianty MJ, Xue B, Kurgan L, Uversky VN. More than just tails: intrinsic disorder in histone proteins. Mol BioSystems 2012; 8:1886-901; PMID:22543956; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1039/c2mb25102g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ejlassi-Lassallette A, Thiriet C. Replication-coupled chromatin assembly of newly synthesized histones: distinct functions for the histone tail domains. Biochem Cell Biol 2012; 90:14-21; PMID:22023434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. du Preez LL, Patterton HG. Secondary structures of the core histone N-terminal tails: their role in regulating chromatin structure. Sub-Cell Biochem 2013; 61:37-55; PMID:23150245; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-94-007-4525-4_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Fontebasso AM, Liu XY, Sturm D, Jabado N. Chromatin remodeling defects in pediatric and young adult glioblastoma: a tale of a variant histone 3 tail. Brain Pathol 2013; 23:210-6; PMID:23432647; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/bpa.12023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Pepenella S, Murphy KJ, Hayes JJ. Intra- and inter-nucleosome interactions of the core histone tail domains in higher-order chromatin structure. Chromosoma 2014; 123:3-13; PMID:23996014; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00412-013-0435-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Peng Z, Oldfield CJ, Xue B, Mizianty MJ, Dunker AK, Kurgan L, Uversky VN. A creature with a hundred waggly tails: intrinsically disordered proteins in the ribosome. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71:1477-504; PMID:23942625; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00018-013-1446-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Malaney P, Pathak RR, Xue B, Uversky VN, Dave V. Intrinsic disorder in PTEN and its interactome confers structural plasticity and functional versatility. Scientific Rep 2013; 3:2035; PMID:23783762; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/srep02035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Malaney P, Uversky VN, Dave V. The PTEN Long N-tail is intrinsically disordered: increased viability for PTEN therapy. Mol BioSystems 2013; 9:2877-88; PMID:24056727; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1039/c3mb70267g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acid Res 1994; 22:4673-80; PMID:7984417; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Shatsky M, Nussinov R, Wolfson HJ. A method for simultaneous alignment of multiple protein structures. Proteins 2004; 56:143-56; PMID:15162494; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/prot.10628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]