A guiding maxim for disaster health professionals is “think locally, act globally.” This is the inversion of the well-worn mantra, “think globally, act locally,” that has been variously attributed to French-born American environmentalist René Jules Dubos and to Friends of the Earth founder David Brower. The original phrasing is perfectly relevant for disaster management. When disaster strikes, emergency response starts locally and expands to incorporate resources from increasingly higher levels, up to the point where capacity is able to match the demands of the disaster event. So why is the obverse, “think locally, act globally,” also particularly on-point for disaster health professionals? There are multiple reasons based on the nature of disasters.

First, by definition, disaster health response relies upon outside help

“A disaster is an encounter between forces of harm and a human population in harm's way, influenced by the ecological context, in which the demands exceed the coping capacity of the disaster-affected population.”1 Disasters impose demands that overwhelm the response resources in the localities where they occur. Therefore, an infusion of outside aid and support is urgently needed.

In a globalized world, disaster health professionals are called upon to respond to each other's extreme events. Creating capabilities to “act globally” when disasters strike elsewhere is becoming increasingly important.

Based on the nature of disasters, strengthening disaster resilience depends upon networking response capacities across communities, regions, and nations, a direct application of the principle “think locally, act globally.”

Second, considering the “place” dimension, most disasters don't happen “here”

Taken at face value, the expression, “think locally, act globally” refers to the place dimension. For the current discussion, consider the geospatial distribution of disaster events.

For disaster health professionals who operate within a specified jurisdiction, a primary responsibility is to start by “thinking locally,” planning effectively for potential extreme events that may affect the home turf. When formulating a hazard vulnerability assessment for the community, one of the fundamentals is determining the types of disasters that can occur locally and with what likelihood, and to rule out very low probability events. For example, while it is self-evident that winter storms do not occur directly along the equator, a lesser-known fact is that neither do tropical cyclones (hurricanes, typhoons, cyclones - the explanation appears in the fourth point below)!

For any particular locality, some types of disasters simply cannot occur and among the litany of extreme events that could pose a significant risk, most occur elsewhere at any given moment.

While planning and preparedness needs to start at home, response must be global based on where disasters actually occur. The geospatial patterning of disasters visually clarifies the need to think locally, act globally.

Third, in the “time” dimension, most disasters don't happen “here and now”

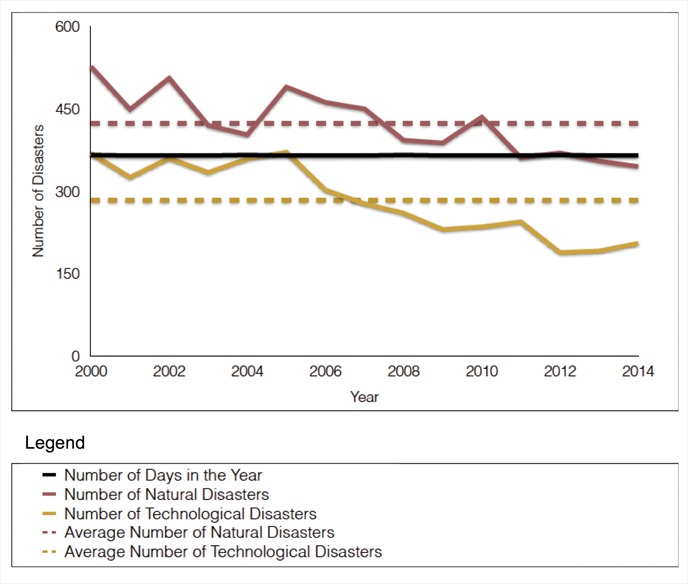

Disasters are locally rare, but globally common (Figure 1). Natural disasters occur with a frequency of slightly more than one per day (for years 2000-2014: 1.16 natural disasters per day).2,3 Technological disasters occur with a frequency of slightly less than one per day (for the 15 years 2000-2014: 0.78 technological disasters per day).2,3

Figure 1.

Annual numbers of natural and technological disasters, 2000-2014.

Violent acts associated with armed conflict occur with a frequency of multiple deadly attacks per day. Complex emergencies and humanitarian crises are continuous and ongoing realities. So, globally, disasters are frequent events. Conversely, disasters are rare phenomena in most communities that are not active conflict zones.

“Today's” disasters are usually not happening “here and now,” in close proximity to the local community. As a corollary, most of today's opportunities for action - engaging in disaster health response and recovery - are occurring in global settings outside of the local jurisdiction.

The temporal perspective, the sequencing of disasters in time, illustrates the paradox that disasters are always striking somewhere but only infrequently happening nearby, so to be part of the action, think locally, act globally.

Fourth, from the perspective of natural disaster risk, there is a strong tendency for these events to concentrate in “hotspots”

Natural disasters are not distributed evenly around the world. Instead, some regions experience specific types of natural disasters with elevated frequency or periodicity. So, on their respective home fronts, some disaster health professionals will be busier – both thinking and acting - than others. Here are 3 examples:

River floods

Consider populations that make their homes in fertile river valleys that are prone to seasonal flooding. Citizens of Fargo, North Dakota, USA, experienced severe inundation along the frigid Red River of the North in April 1997; thereafter, Fargo's “flood fighters” successfully fended off 14 consecutive years of river rises above flood stage.4

Tropical cyclones

Consider large urban centers and multitudes of communities that have populated coastal areas in semi-tropical latitudes bordering the 7 tropical cyclone “basins.” These coastal dwellers regularly experience impacts from tropical storms, typhoons, cyclones, and hurricanes with strong winds, drenching rains, and storm surge.5

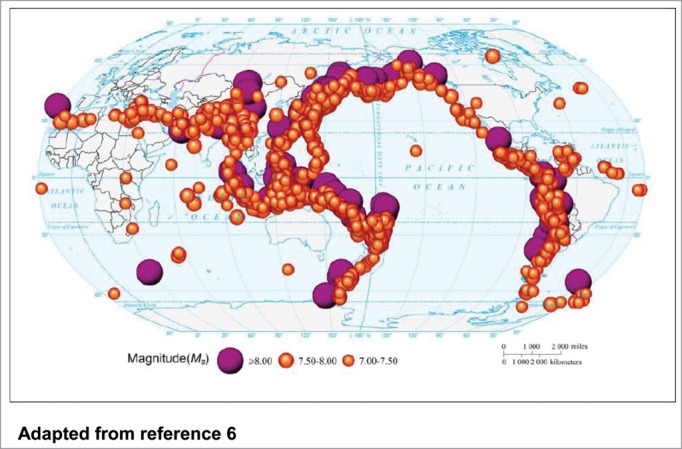

Earthquakes

Consider large proportions of the world's inhabitants living in areas with elevated risks for earthquakes. Seismically active regions have been plotted with precision on world maps and they closely align with the earth's crustal masonry; geophysical disasters tend to occur along tectonic plate boundaries (Figure 2).6

Figure 2.

Historical event locations of earthquakes ms >7.00, 1900-2009. Adapted from reference 6.

In terms of types of disasters, it is important to clarify that a hotspot for one is not a hotspot for all. As a potent example, Indonesia is recognized as the most hazardous nation on earth for both earthquakes and volcanoes. Indonesia was the point of origin of the earthquake-triggered 2004 Southeast Asia tsunami. This multi-island nation is situated directly over the equator, floating in some the planet's warmest ocean waters. Monumental thunderheads rise above the sea surface. Yet Indonesia has almost no risk for tropical cyclones. Why? The effect of the earth's rotation that “spins” thunderstorms into tropical cyclones only operates at distances exceeding 500 km north or south of the equator.5

Human actions are profoundly affecting the frequency and severity of natural disasters. The expanding human population, coupled with increasing settlement in disaster hotspots and collective behaviors that increase risks on a planetary level, have combined to amplify the likelihood of natural disasters.

As disaster health professionals gain expertise and specialize, some will be called upon regularly to respond to particular types of disasters. Even with the tendency for natural disasters to cluster in hotspots, the countable active events taking place in global hotspots at any point in time are much more likely to be happening in distant sites than local.

From the vantage of natural disaster risk, disaster health professionals, especially subject matter experts, are guided to think locally, act globally.

Fifth, non-intentional human-generated (“anthropogenic”) disasters are increasing in prominence as human technologies proliferate and sporadically fail, producing a concatenation of risks

The global population is both enlarging and urbanizing, leading to occupational specialization, interdependency, and increasing reliance on human technologies. In turn, technological disasters occur regularly, including widespread power blackouts (example: 2006 European power blackout affecting 15 million persons), hazardous materials spills (example: 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico7), transportation crashes (example: 2013 Alvia train derailment in Santiago de Compostela, Spain), radiation emergencies at nuclear power plants (example: 2011 reactor meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan8), structural collapses (example: 2013 Savar garment factory building collapse, Bangladesh) and incendiary events (example: 2015 explosion at a chemical warehouse, Tianjin, China).

The field of disaster management is becoming professionalized and increasingly sophisticated. Event-specific disaster health expertise and response capabilities are becoming available but in a limited number of locales; for optimal response, these assets need to be activated and deployed to the scene of a major technological incident. Many technological disasters are highly focalized events so the response may initially rely upon local “generalists” until they can be supplemented by outside expert resources. Once the reinforcements arrive, skills and “person power” can be combined synergistically to create a disaster response that is proportional to the demands of the situation.

Anthropogenic disaster risks require the ability to improvise and adapt a disaster health response to the novel features of the event, and to import resources as needed; this represents a very pragmatic application of think locally, act globally.

Sixth, risks associated with intentional human-generated (“anthropogenic”) events represent one of the most compelling reasons to think locally, act globally

Intentional acts of mass violence span the gamut from declared war to armed insurgency to acts of terrorism. Harm is intended and perpetrated by humans against humans.

A powerful rationale for disaster health professionals to “think locally, act globally” is based on the fact that this is precisely the strategy employed by terrorist groups – with devastating effect. In a world of asymmetric engagement, there have been repeated attacks that have been conceived by a handful of belligerents and launched from faraway locales to strike deep into the core of nations with vastly superior military might (September 11, 2001 attacks, 2004 Madrid train bombings, 2005 London “tube” attacks). The blatant audacity of these incidents routinely takes the targeted nations by surprise.

Further complicating the situation, the terrorist organizations themselves are morphing into unexpected forms, making it more difficult to prepare for attacks. For example, the ascendant rise to power of a succession of terrorist organizations in the Middle East has been a game changer. These groups experiment continuously with promotional strategies that have swelled their ranks and created converts willing to cause catastrophe around the world. Tactics have included the shrewd use of social media to attract and radicalize disaffected youth, and the dissemination of media of high cinematographic quality portraying military invasions, atrocities, and desecration of historic artifacts, justified as righteous acts.

Terrorism is “psychological by design,”9 and the outcomes of these attacks are far-reaching and enduring, including fundamental shifts in societal behaviors (air travel) and worldviews (perceptions regarding personal safety, optimism, and beliefs in positive futures), negative economic impacts, and pervasive, lingering distress. These attributes especially describe the legacy of the attacks of September 11, 2001.9

Psychologically speaking, terrorism congeals the “perfect storm” of stressors: 1) acts of terrorism are unpredictable, incorporating the element of surprise to amplify the impact; 2) acts of terrorism are unfamiliar (terrorists “think the unthinkable” and then perpetrate these acts); 3) acts of terrorism appear to be uncontrollable; and 4) the threat of terrorism is “unrelenting.”9

Meanwhile, the failure to adopt a “think locally, act globally” philosophy has relegated many nations to the “reactive” posture of planning extensively for a finite and logical set of disaster scenarios – primarily variations on historical “known” events. The upside of this approach is the construction of comprehensive plans for a spectrum of disaster events. The downside of this approach is to broadcast the scenarios that disaster planners are envisioning along with the game plans for response. As a byproduct, this process also telegraphs the “playbook” to those who wish to cause harm and facilitates the “enemy” in devising attacks that end-run around current planning initiatives. Furthermore, planning exhaustively for highly specified scenarios is doomed to failure because real-world events will not hold to script – and terrorists write their own. Terrorism has achieved global reach in part because active minds have been thinking circles around conventional wisdom. This has not been adequately matched on the side of disaster planning and preparedness.

Facing the proliferation of intentional, human-caused disasters, societal health and preservation demands that disaster health professionals think locally, act globally.

Seventh, disasters are complex phenomena

Disasters cascade.10 When disasters strike, things go rapidly from bad to worse as consequences multiply.10

Disaster math does not work according to the probabilities of chance. The frequency of disaster occurrence, as well as the convolutions of spin-off complications, is not readily predicted by traditional methods. As a simple example, only a few years after the risk estimates are published, communities are battered by the “100-year” storm or submerged by the “500-year” flood. In 2015, California has experienced a “1,200-year” drought. During the Great East Japan disaster, tsunami waves easily overtopped the supposedly insurmountable seawalls around the Fukushima Daichii nuclear power plant, scuttling the reactors and also the calculated projections of probable tsunami wave heights, based on historical experience. Disaster planning, from local to global, needs to use better math that is informed by the complexity of disaster events.

In the realm of technological disasters, no one predicted the challenges inherent in plugging a pipe, so the Deepwater Horizon wellhead blowout resulted in 87 days of unabated petroleum flow into the Gulf of Mexico. Moreover, the very human ingenuity that has delivered a series of technological triumphs also has a tendency to go off the tracks, sometimes literally, as evidenced by the spate of recent deadly rail crashes (examples: 2013 passenger train derailment in Santiago de Compostela, Spain; 2013 runaway oil train explosion in Lac Mégantic, Canada).

In the realm of natural disasters, Mother Nature is not constrained to behave according to the principals of logic. Nevertheless, sometimes planners are spot-on. The flooding of New Orleans that occurred during Hurricane Katrina in 2005 had been predicted with precision in the 2004 “Hurricane Pam” simulation. Tragically, no action was taken based on this knowledge and harm was compounded by failing to warn and evacuate citizens who were known to be in danger, resulting in the preventable loss of hundreds of lives.

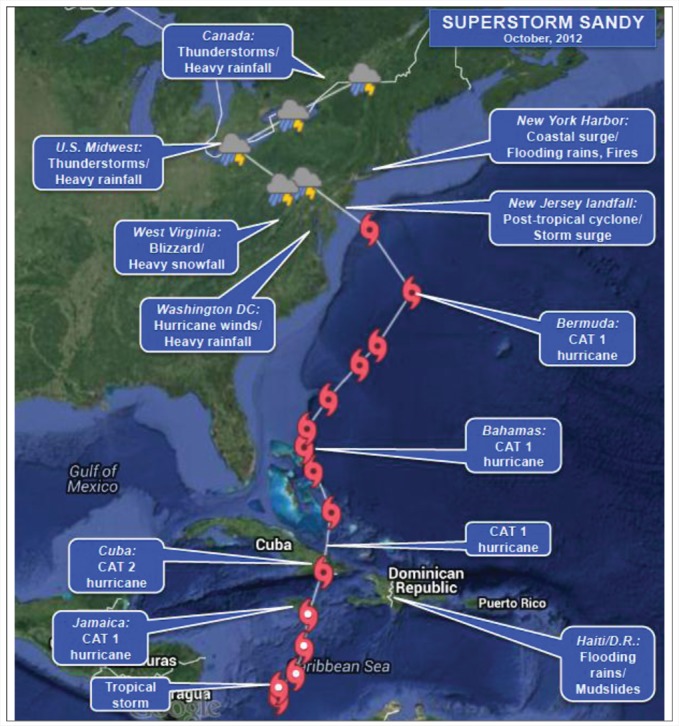

Disasters throw curve balls. Because of the “emergent” properties of complex systems, some disasters that initially appear to be typical and tame may evolve into devastating monster events. Case in point: consider the damage and disruption wrought by “Superstorm” Sandy. In late October 2012, starting out as a meandering Caribbean tropical storm, Sandy strengthened slightly to Category 1 hurricane status as it passed directly over Jamaica and then reached high Category 2 intensity over Cuba before the winds settled back to Category 1. Sandy gave no indication of being a “super” storm except for its very broad canopy. Sandy would ultimately roam across a vast expanse of global real estate (impacting 8 nations and 24 US states) while maintaining a relatively low intensity cyclonic circulation.

We have previously described Sandy as a “meteorological chimera” because the storm presented so many different “faces” along its trajectory – tropical storm, hurricane, mudslide, coastal surge event, storm surge event, windstorm, thunderstorm, winter storm, flood – creating a constant challenge for disaster response (Figure 3).11,12 Along its path, Sandy crippled human-made infrastructures of all sorts, submerging East River tunnels, flooding the New York City subway system, and knocking out electrical power to millions.

Figure 3.

Superstorm Sandy, 2012. Multiple hazard presentations along the storm trajectory.

As an indicator of complex systems as work, Sandy was characterized by the curious juxtaposition of a very late season tropical storm that joined forces with a very early season winter storm to produce havoc. Researchers speculate that global climate change contributed to Superstorm Sandy's formation over unseasonably warm Caribbean waters.

Grounded on the fact that the risk landscape is globally networked and disaster complexity creates rippling consequences, disaster health professionals must think locally, act globally.

Concluding thoughts

Disasters cause disasters. Disaster events rapidly scale upward and grow complex and their consequences circumnavigate the globe. This is readily demonstrated in the case of airborne pandemic diseases. The speed with which the H1N1 influenza wrapped around the planet to become the dominant strain of influenza in 2009 was breathtaking. World citizens were spared from mass mortality only by the fact that the 2009 virus was neither highly pathogenic nor virulent. There will be a very different saga if a future influenza strain more closely approximates the highly-lethal “slate-wiper” influenza of 1918/1919 that killed 50–100 million persons on a much more sparsely populated planet.

Periodic wake-up calls, like pandemic influenza, punctuate the steady cadence of multiple daily disaster events, reminding disaster health professionals to think - and prepare - locally, but to increasingly prioritize our capabilities to act - and respond - globally.

References

- 1.Shultz JM, Espinel Z, Galea S, Reissman DE. Disaster ecology: implications for disaster psychiatry In: Ursano RJ, Fullerton CS, Weisæth L, Raphael B (eds): Textbook of Disaster Psychiatry. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2007. p. 69-96. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guha-Sapir D, Hoyois P, Below R. Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2013: The Numbers and Trends. Brussels, Belgium: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) EM-DAT international disaster database. Brussels, Belgium Available at: http://www.emdat.be. Accessed 22 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shultz JM, McLean A, Herberman Mash HB, Rosen A, Kelly F, Solo-Gabriele HM, Youngs GA Jr., Jensen J, Bernal O, Neria Y. Mitigating flood exposure: reducing disaster risk and trauma signature. Disaster Health 2013; 1(1):30-44; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/dish.23076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shultz JM, Russell JA Espinel Z. Epidemiology of tropical cyclones: the dynamics of disaster, disease, and development. Epidemiol Rev 2005; 27(1):21-35; PMID:15958424; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/epirev/mxi011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M, Zou Z, Xu G, Shi P. Mapping earthquake risk of the world In: IHDP/Future Earth-Integrated Risk Governance Project Series: World Atlas of Natural Disaster Risk. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2015. p. 25-39. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shultz JM, Walsh L, Garfin DR, Wilson FE, Neria Y. The 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill: the trauma signature of an ecological disaster. J Behav Health Serv Res 2015; 42(1):58-76; PMID:24658774; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11414-014-9398-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shultz JM, Forbes D, Wald D, Kelly F, Solo-Gabriele HM, Rosen A, Espinel Z, McLean A, Bernal O, Neria Y. Trauma signature of the Great East Japan Disaster provides guidance for the psychological consequences of the affected population. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013; 7(2):201-14; PMID:24618172; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/dmp.2013.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shultz JM, Espinel Z, Flynn BW, Hoffman Y, Cohen RE. DEEP PREP: All-Hazards Disaster Behavioral Health Training. Tampa, Florida: Disaster Life Support Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shultz JM, Espinola M, Rechkemmer A, Cohen MA, Espinel Z. Prevention of disaster impact and outcome cascades In: Israelashvili M, Romano JL (eds.), Cambridge Handbook of International Prevention Science. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shultz JM, Neria Y. The trauma signature of Hurricane Sandy: a meterological chimera. Online at: The 2´2 project, Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology. Published 14 November 2012 Available at: http://the2´2project.org/the-trauma-signature-of-hurricane-sandy/ Accessed 22 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neria Y, Shultz JM. Mental health effects of Hurricane Sandy: characteristics, potential aftermath, and response. JAMA 2012; 308(24):2571-2; PMID:23160987; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.2012.110700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]