Introduction

Psychological and social impacts of disasters undermine the long-term well-being of affected populations. Integrated, community based MHPSS interventions potentially improve emotional, social, and mental well-being. Post emergency, a focus on mental health, paired with professional understanding of disaster effects, can improve community mental health services. Moderate to severe psychological distress develops in 30 to 50% of disaster affected people. The incidence of common mild to moderate mental disorder (mood and anxiety disorders) is expected to increase by 5 to 10%, and incidence of severe mental disorders may rise by 1 to 2%.1

Mental Health Standards and Indicators presented in the 2011 Sphere Handbook provide reference for the acute emergency phase of a humanitarian crisis.2 The main objectives of a disaster setting MHPSS intervention endeavor to: A) improve emotional, mental and social well-being of beneficiaries,3 B) enhance resilience and empower individuals to tackle emotional reactions to critical events,4 C) manage stress and its related disorders to prevent development of more severe mental health problems,5 D) support families and groups by activating support networks,6,7 E) increase MH awareness, mitigate stress and restore social and cultural constructs in communities;6,7 and F) ensure provision of MHPSS services to address more severe mental problems.8

Capacity building for mental health service providers (community psychosocial and non-specialized healthcare providers) is often a pre-requisite for evidence-based MHPSS intervention in disaster affected populations.9 Mental health effects of disaster are best addressed through existing services, and capacity building initiatives to enhance these services; rather than the development of parallel systems.10 MHPSS interventions in complex emergencies should begin with a clear vision toward longer term goals for community mental health services.11

Saraceno12 relates that a professional approach to disasters’ effects, paired with a post-emergency focus on mental health, can provide opportunity for MH system development. Enhancing MH care is an important component of health system strengthening. Countries have improved their MH services following major manmade or natural disasters.13-16 After the Haiti earthquake, one response of the World Health Organization (WHO) focused on MHPSS for affected populations as well as improvement of MH services.17

MHPSS needs and services in Haiti

There is no epidemiological study on the prevalence of mental illness in Haiti. Pre earthquake studies on conjugal violence found high levels of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and somatic symptoms.18 After the 2008 hurricane in Gonaives, a majority of nutritional program beneficiaries suffered from depression.19 In 2011, there were only 0.2 psychiatrists and 0.04 psychologists per 100,000 Haitians, and number of persons treated in MH outpatient facilities was 48.3 per 100,000.20 Comparatively, in the neighboring Dominican Republic, in 2011, there were 1.3 psychiatrists and 3.3 psychologists per 100,000 and 384.1 persons per 100,000 were treated in MH outpatient facilities.21 Most services provided by MH professionals in Haiti were in the private sector, and based primarily in the capital Port-au-Prince.22 Many Haitians, especially of lower education and economic status, made use of traditional practitioners for mental illness. These practitioners included herbalists (dokte fey); and male (houngan) or female (mambo) voodoo priests. Also, Christian churches helped people cope with mental and emotional issues.23 Past efforts have mobilized community resources to sensitize the population to the social and public health issues such as violence against women, HIV/AIDS and children’s rights. These grassroots organizations brought self-help methods and support groups to people facing traumatic life events and stressors.22

An estimated 220,000 people lost their lives and over 300,000 were injured in the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Roughly 2.8 million people were affected and nearly 1.5 million found themselves without a home.17 It was estimated that there were 190,000 people in Port-au-Prince alone suffering from symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).24 Headaches, sleeping problems, anxiety and fatigue were being reported in more than half the families in displacement camps. Almost one-third of families reported a major distress indicator (panic attack, serious withdrawal, or suicide attempt) in at least one family member.25 Existing MH service organizations were affected through destruction of infrastructure and death of staff. Most of these organizations, with help from the international community, resumed some activities very rapidly.

After the earthquake, interventions were coordinated through the Cross-Cluster Working Group on MHPSS directed by UNICEF and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). WHO led this working group and actively partnered with the Haitian Ministry of Public Health and Population (MPHP) to support MHPSS interventions. At one point this working group included more than 110 organizations providing MHPSS.17 One of those organizations, the Dutch international non-governmental organization (INGO) Cordaid delivered a community-based integrated MHPSS intervention of service delivery and capacity building for providers. Cordaid’s project was designed to improve the well-being of the earthquake-affected population by reducing levels of distress and enhancing resilience in the targeted communities. Simultaneously, the intervention aimed to ensure provision of MHPSS services for more severe MH illness. This study of Cordaid’s program provides description, evaluation, and discussion of the intervention’s contribution to community based MH care and psychosocial support services in post-earthquake Haiti.

Methods

Setting, provider, participants

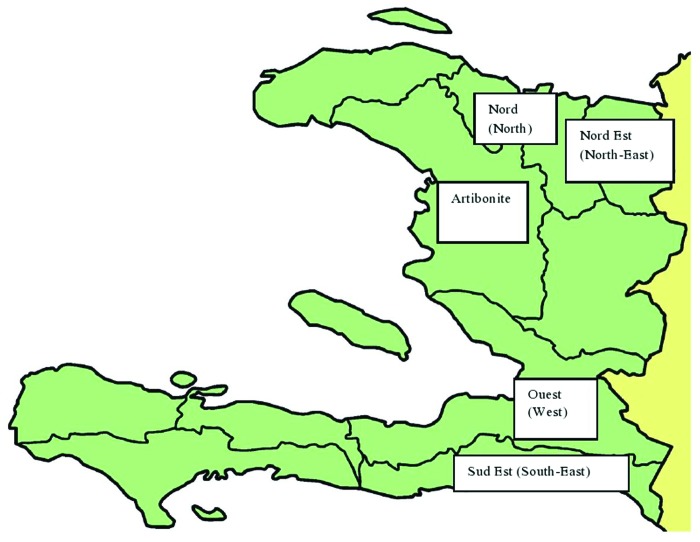

Cordaid’s MHPSS programming was conducted from October 2010 to June 2012 in five departments of Haiti with estimated total population of 7,139,705.26 Selection of areas for intervention was done in consultation with the major donor European Community Humanitarian Office (ECHO) and local non-governmental (NGO) partners. Selections were based on population needs and geographic locations of partners. The economy of Haiti primarily depends on the agricultural sector, mainly small scale subsistence farming. Even before the 2010 earthquake, the economy was vulnerable to damage from frequent disasters. The economies of all departments suffered severe setbacks in January 2010, when the 7.0 magnitude earthquake destroyed much of the capital city.27 An extensive literature review and a comprehensive field-based assessment concluded that MHPSS should be one priority for health sector interventions post-earthquake.28

Cordaid began its program with the hiring of one expatriate psychiatrist with extensive post-disaster experience and 12 local staff members. The local staff included two general practitioners, five psychologists, and five social workers; selected through a field-based interview process. This group formed Cordaid’s multi-disciplinary MHPSS team in charge of project implementation. Five smaller teams of psychologists and social workers were later formed and dispatched to targeted departments. The expatriate psychiatrist and the two general practitioners administered the program from a Port-au-Prince base; with frequent visits to the field. Senior local consultants were used throughout the project as trainers and supervisors.

The 12 local NGO partners chose 190 community psychosocial workers and 115 non-specialized healthcare providers from five departments to staff their programs (Fig. 1, Table 1). Community psychosocial workers were selected based on a keen interest in assisting the affected population and a broad knowledge of their community. Non-specialized healthcare providers were selected based on existing responsibility for general health care in their communities. Staff selected included general practitioners, nurses, psychologists, social workers and non- mental health specialists. Non-specialist healthcare providers also were selected based on keen interest in the training provided by the program and a commitment to the ongoing practice of general healthcare after program completion. Personal characteristics and professional qualifications were also considered. Senior local consultants were also chosen; those roles were filled by psychiatrists, general practitioners, psychologists, and social workers.

Figure 1. Map of Haiti and its departments.

Table 1. Departments in Haiti with their estimated population, number of direct beneficiaries and the breakdown of training participants.

| Department | Number of trained psychosocial community workers | Number of trained non-specialized healthcare providers | Number of direct beneficiaries | Estimated population of department (source and year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nord (North) |

25 | 13 | 13,948 | 970,495 (IHSI,2009) |

|

Ouest (West) |

80 | 60 | 52,527 | 3.664,620 (IHSI,2009) |

|

Nord Est (North East) |

20 | 14 | 12,897 | 358,277 (IHSI,2009) |

| Artibonite | 33 | 16 | 24,238 | 1.571,020 (IHSI,2009) |

|

Sud Est (South East) |

32 | 12 | 11,581 | 575,293 (IHSI,2009) |

| TOTAL | 190 | 115 | 115,191 | 7.139,705 |

Direct beneficiaries were selected by local NGO partners based on inclusion criteria determined by the Cordaid team and ECHO. The main criterion was belonging to a population affected by the earthquake whether remaining in an affected area or moving as an internally displaced person (IDP) to another department. The host populations in departments assisting IDPs could also be beneficiaries if they had need for MHPSS. The selected population of direct beneficiaries was 55% female, 45% male. Children under five totaled 17.8% of beneficiaries and those between six and 17 y were 23.7% of this population. Senior citizens over 65 y comprised 0.13% of the total group.

Intervention

Objective

This study evaluates a community-based integrated MHPSS intervention that was designed to improve the emotional, mental and social aspects of the well-being of beneficiaries. Specific objectives of the intervention included reducing levels of distress, strengthening resilience, building MHPSS capacity of community psychosocial workers / non-specialized healthcare providers, and providing MH services for the treatment of more severe disorders.29 The objectives and the content of the community-based integrated MHPSS intervention were discretely designed by the Cordaid’s MHPSS team after close and regular discussion with local mental health experts and Haitian NGO partners (Table 2 and 3).

Table 2. Title, objective and content of each level of MHPSS training intervention.

| No. | Title of the training | Learning objective | Content of training |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Basic training of community psychosocial workers | To become familiar with MHPSS, most common MH problems and basic MHPSS interventions in communities | Definition of MHPSS, Psychosocial interventions, Resilience, Vulnerable groups, Stress / Distress, PTSD, Bereavement, Anxiety, Depression, Psychosis, Communication skills, Stress management, First psychological aid, Problem solving, Individual psychological and family and group support |

| 2. | Advanced training of community psychosocial workers | To learn practical skills in providing MHPSS interventions in communities | Verbal and non-verbal communication, Exploration of personal stressful events, Identification of personal anxiety, Learning to relax, Learning how to conduct support group, Learning about family support, Playing with children, Cognitive therapy, Diary sheet for somatic problems, Sleep diary exercise, PTSD and domestic violence (psychodrama) |

| 3. | Final training of community psychosocial workers | To become familiar with specific MH problems and MHPSS to vulnerable groups and to learn about mental health system | Child abuse, Disability by mental problems, Community mobilization, Psycho-education, Working with children, Anger management, Conflict resolution, MH system, MH educational resources |

| 4. | Basic training of non-specialized healthcare providers | To become familiar with most common MH problems and basic MHPSS interventions in general healthcare and role of traditional healing system | Stress / Distress, Priority MH conditions, Depression, Self-harm, Psychosis, Developmental and Behavioral disorders, Epilepsy, Medically unexplained complaints, Alcohol and Drug disorders, PTSD, General principles of care, Psychosocial interventions, Family and peer support, Essential MH medicines, Effects of stressors on children, MHPSS within traditional healing system |

| 5. | Advanced training of non-specialized healthcare providers | To learn practical skills in providing MHPSS in general healthcare and to learn about organization of general healthcare services, referral system and collaboration with traditional healers | Case studies of Psychosis, Depression, Bipolar disorder, Behavioral and Developmental disorders, Alcohol and Substance abuse, Dementia, Epilepsy and emotional somatic symptoms, Examples of problem solving therapy for sleep problem and cognitive therapy for depression, Organization of general healthcare services and referral system, Collaboration between traditional healers and health system |

| 6. | Final training of non-specialized healthcare providers | To become familiar with MH diagnostic tools and MH emergencies, MH problems of vulnerable groups and to learn about public MH system and community MH services | Psychiatric history and mental status examination, Psychiatric emergencies, Behavioral and emotional disorders in children, Mental retardation, Mental problems in women, Disability by mental disorders, Psycho-education, Public MH system, Integrating MH into primary healthcare, MH policy, Educational MH resources |

Note: Cordaid's MHPSS local managerial team received training on all above mentioned topics.

Table 3. Title, objective, and content of community-based MHPSS activities.

| No. | Title of the activity | Objective of the activity | Content of the activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Individual psychosocial support | To manage stress and enhance resilience of individuals | stress management, positive coping strategies, problem solving, first psychological aid, anger management, psycho-education |

| 2. | Group / Family psychosocial support | To manage stress and enhance resilience in families and groups | peer-support groups, family support groups, stress management |

| 3. | Community mobilization and sensitization | To manage stress and enhance resilience in communities | mobilization and sensitization of communities around MH issues, psycho-education |

| 4. | Recreational and Occupational / Vocational activities | To mitigate the effects of stress in communities | summer camps for children, celebrations of different local and international holidays, musical events, football and domino championships, cooking classes |

| 5. | MH consultations | To ensure provision of MHPSS services for people with more severe MH problems. | MH consultations by non-specialized healthcare providers |

Design

The MHPSS intervention lasted 18 mo, with three cycles totaling 90 h of training provided to separate groups of the community psychosocial workers and the non-specialized healthcare providers. Training group size varied from seven to 33 people. A one-day MHPSS joint-workshop for both groups in selected areas aimed to improve coordination between communities and the health system. Weekly individual, family and group MHPSS sessions were provided to targeted communities. Occasional activities occurred for community mobilization, sensitization, recreation, and focus on occupations and vocations (Table 3). Trained community psychosocial workers referred beneficiaries with more severe MH problems for consultations with the trained non-specialized healthcare providers.

The intervention had 4 stages: 1) development of manuals for community psychosocial workers and non-specialized healthcare providers, 2) actual training of the two groups, 3) delivery of the community-based MHPSS intervention delivered by the trained psychosocial workers and 4) MH consultations by the trained healthcare providers to people with more severe MH problems.

Initially, manuals were developed for the workers to be trained. WHO’s module for psychosocial caregivers developed after the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan30 was adapted to the Haitian context and used as a manual for community psychosocial workers. MHPSS presentations for that group were developed by the expatriate psychiatrist and translated by Cordaid's managerial team into the local language (Creole). The manual and presentations for the non-specialized healthcare providers were based on the mhGAP Intervention Guide developed by the WHO.31 Training of trainers for Cordaid's local managerial team was held in Cordaid's office in Port-au-Prince. This team then held training sessions for community psychosocial workers and non-specialized healthcare providers in the premises of local NGO partners in each of five targeted departments. The training staff included the Cordaid's local managerial team, one international and three local psychiatrists, eight senior local psychologists and five senior local social workers. Active adult learning methods and participatory approaches were preferred to formal lecturing, although all these methods were used. Trained community psychosocial workers delivered MHPSS activities in targeted communities and referred people with more severe MH problems for consultations with the trained non-specialized healthcare providers.

Evaluation

The training intervention was evaluated according to the following criteria: 1) trainee satisfaction with training; 2) enhancement of trainee theoretical MHPSS knowledge; and 3) on-the-job implementation of newly acquired MHPSS knowledge and skills by the trainees. All 190 community psychosocial workers and 115 non-specialized healthcare providers were evaluated for the first two criteria. For the third on-the-job criterion, all community psychosocial workers were evaluated; but only 15 of the trained healthcare providers were evaluated.

Valuable feedback was gained from a 4-point Likert scale survey28 on satisfaction with various aspects of training including: 1) clarity of presentations; 2) usefulness of knowledge gained on MHPSS issues; 3) ability of trainees to transfer knowledge gained; 4) time allocated for questions; 5) treatment of participants during the training; and 6) appropriateness of training materials to the Haitian context. A 2item multiple choice knowledge tests designed by Cordaid’s ex-pat psychiatrist and translated by Cordaid’s MHPSS team into French were used to evaluate knowledge of participants’ pre and post each training level. Tested knowledge categories included: 1) stress/stress related problems and disorders; 2) common and severe MH problems and disorders; 3) MHPSS interventions for community psychosocial workers; 4) MHPSS interventions for non-specialized healthcare providers; and 5) the public MH system and community MH services. The tests were in French because the majority of training participants were able to understand questions in French. The face validity of the tests was determined by local trainers, as a representative sample of the training participants in the population of interest. The content validity of the tests was determined by the international staff, and it was satisfactory. Finally, the on-the-job implementation of newly acquired MHPSS knowledge and skills, namely the community-based MHPSS intervention implemented by the psychosocial workers and the MH consultations performed by the non-specialized healthcare providers, were evaluated. Observation and evaluation occurred during supportive supervisions in the field which were conducted by Cordaid's local MHPSS team, the expatriate psychiatrist and local consultants.

The evaluation of the community-based MHPSS intervention was performed using quantitative community surveys with randomly selected representative samples of direct beneficiaries in all departments. A 7-point Likert well-being scale was created based on the integrated programming for well-being intervention.3 It provided valuable information in regard to satisfaction of beneficiaries with different aspects of their well-being (economic, family, social, emotional, mental and spiritual). The 5-point Likert distress scale was a modified 14-item perceived stress scale32 and the 7-point Likert resilience scale was a modified 14-item resilience scale33 (Table 4). All scales were finalized by Cordaid’s expatriate psychiatrist and translated by Cordaid’s MHPSS team into French and /or Creole. Local trainers provided assistance for translation from French into the local language (Creole).The face validity of all instruments was determined by local trainers, as a representative sample of the earthquake-affected population and training participants. The content validity was determined by the international staff and senior local consultants, and it was satisfactory.

Table 4. Questions on 7- item Likert distress and resilience scale.

| Question No. | 7-item Likert distress scale | 7-item Likert resilience scale |

|---|---|---|

| 1. |

How often in the past month: Have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? |

I agree / disagree with following statement: I usually manage one way or another |

| 2. | How often have you felt nervous or stressed? | I feel that I can handle many things in time |

| 3. | Have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal and family problems? | I can get through difficult times because I have experienced difficulties before |

| 4. | Have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | I have self-discipline |

| 5. | Have you been able to control irritations in your life? | I keep interested in things |

| 6. | Have you had family disputes? | I can usually find something to laugh about |

| 7. | Have you been angered because of things that were outside of your control? | My life has meaning |

Results

MHPSS training intervention

At one year, the MHPSS training intervention increased the likelihood that the 190 psychosocial workers would properly provide community-based MHPSS activities. It also increased the likelihood that the 115 non-specialized healthcare providers would properly manage MH problems in general healthcare. The results were evaluated every three to four months, at the beginning and at the end of each training cycle. The calculated averages were based on individual scores per participant. Tested knowledge was improved for all trainees in 4 out of 5 departments. A large majority of the participants expressed satisfaction with all aspects of the training, although community psychosocial workers were more satisfied than non-specialized healthcare providers (Table 5).

Table 5. Improvement of knowledge and satisfaction of training participants.

| Knowledge improvement (%) | % of satisfied participants (with all aspects of training) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Training of psychosocial community workers | Training of non-specialized healthcare providers | Training of psychosocial community workers | Training of non-specialized healthcare providers |

| Ouest (West) | 21.7 | 27.9 | 90.5 | 69.8 |

| Artibonite | 19.7 | 26.5 | 85.3 | 76.3 |

| Nord (North) | 24.7 | 24.1 | 90.9 | 71.9 |

| Nord-Est (North-East) | 20.4 | 24.1 | 98.1 | 75 |

| Sud-Est (South-East) | 4 | 22 | 91.3 | 80.8 |

| TOTAL AVERAGE | 18.1 | 24.9 | 91.2 | 74.8 |

MH Consultations by Providers

Community psychosocial workers identified more severe MH disorders in 1% of the total number of beneficiaries, and referred these individuals for consultations. Of those referred, about one third received MH consultations by the trained non-specialized healthcare providers. Altogether, 616 MH consultations were performed by those providers in four departments

(Table 6).The majority of severe MH problems were described as epilepsy, depression and psychosis. Three-fourths of referred beneficiaries received the psychosocial support intervention as well as medications, and the remainder received only psychosocial support. Supervisors’ observations suggested that overall a good level of cooperation was achieved between community psychosocial workers and non-specialized healthcare providers, but there was a persistent gap between results achieved in training and the practices observed in patient encounters.

Table 6. Percentage of referred beneficiaries with consultations by providers.

| Department | % of referred beneficiaries who received consultations by non-specialized healthcare providers | % of referred beneficiaries who received medications |

No. of consultations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st consultation | 2nd consultation |

|||

| Artibonite | 48 | 52 | 54,9 | 165 |

| Nord-East (North-East) |

36.5 | 63,6 | 83,2 | 138 |

| Sud-Est (South East) |

13.3 | 86,7 | 70 | 248 |

| Ouest (West) | 39.3 | 60,7 | 95 | 65 |

| TOTAL Average | 34.3 | 65.8 | 75.8 | 616 |

Community-based MHPSS intervention

After the community-based MHPSS intervention, the surveyed level of well-being of direct beneficiaries improved and surveyed level of distress was reduced in all five departments (Table 7). The initial evaluations of well-being and distress took place at the start of the community MHPSS intervention in each department, and the final evaluation was accomplished one year later after the end of the intervention. The averages were based on individual scores of representative samples of beneficiaries. The sample size ranged from 398 to 429 people based on size of targeted population of the department. The calculated Pearson correlation coefficient of 0, 92 (P < .05) showed high correlation between reduced level of distress and improved well-being of beneficiaries. Resilience was measured as an indicator of a smaller complementary 6-mo project intervention which took place in four departments after the end of main one year project, and it was measured at the beginning of intervention and again at the end of six months.

Table 7. Results of community-based MHPSS intervention on well-being, level of distress and resilience of beneficiaries.

| Improvement (%) | Reduction (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Well-being | Resilience | Level of distress |

| Ouest (West) | 30.2 | 29.1 | 51.1 |

| Artibonite | 14 | 38.6 | 40.1 |

| Nord (North) | 30.9 | 56 | |

| Nord-Est (North-East) | 42.5 | 28.4 | 49.4 |

| Sud-Est (South-East) | 16.9 | 28.1 | 41.1 |

| TOTAL AVERAGE | 26.9 | 31.1 | 47.5 |

Discussion

This study adds to the growing evidence on community-based integrated MHPSS interventions provided in post-disaster settings as emergency assistance. In addition it explores the attempt to enhance access to community MH care and psychosocial support services in resource poor settings as part of the post-disaster intervention.11 The rationales for selecting a community-based integrated MHPSS intervention in Haiti were the neglected MH sector, the gap between MH needs and services before the earthquake22 and the increased MHPSS needs after the earthquake.17 In responding to MHPSS needs of the population in post-earthquake Haiti, it was important to take a broad integrated approach that included more than the provision of direct services.34 The study showed that the aims of MHPSS interventions in disaster settings were met. The interventions contributed to: A) improved well-being of targeted beneficiaries; B) strengthening of their resilience; C) management of stress and stress related problems; D) activation of family and social support networks; E) mitigation of the effects of stress in communities; and F) provision of MHPSS services for those with more severe mental disorders. Attributing these results solely to this intervention is not justified as other factors may have contributed as well. These factors included other interventions by NGOs, the passage of time, and gradual return to normal life.35 Other modalities of MHPSS intervention applied by NGOs in Haiti included: a) local and foreign mental health professionals providing short-term direct clinical care for mental health disorders; b) the training of lay volunteers, local psychologists and general practitioners on MHPSS issues; c) organization of child friendly spaces; d) individual and group psychological support; e) recreational activities for beneficiaries; and f) advocating for mental health issues.36 The effects of Cordaid’s interventions may have been greater in many areas of the intervention where MHPSS was not offered by any other NGO.

It is estimated that the majority of people recover from stress and return to normal life sometime after disaster, even without any intervention.1 However, natural recovery from stress and return to normal life was slow for the majority of Haitians because major stressors arose even after the earthquake; e.g., political unrest, cholera outbreak, living in IDP camps and food insecurity. These stressors affected the trainers as well as the beneficiaries. The training environment was difficult due to huge loss of life, extensive destruction, political unrest, and cholera. In spite of the situation, the average improvement in MHPSS knowledge after trainings was similar to that achieved with MH trainings in other countries faced with disasters and/or complex emergencies.37-39 The satisfaction of participants with training ranged between 70–98%. Comparatively, satisfaction with the MH training in Grenada ranged between 67–93%.37 Overall, the training of community psychosocial workers was successful in gradually building their capacity to provide an effective community-based MHPSS intervention. Although the great majority of non-specialized healthcare providers expressed much interest in training, a significant number of them were not satisfied with various aspects of the training. Those aspects were specifically time allocated for questions and adaptability of training materials to the Haitian context.29 With respect to actual on-the-job performance during MH consultations, supervisions in the field confirmed that it was more difficult for non-specialized healthcare providers to implement newly acquired skills than to understand them. Although community psychosocial workers were able to identify a small percentage of beneficiaries with more severe MH problems in need of referral, only one third of them received MH consultations by non-specialized healthcare providers. Financial incentive with non-specialized healthcare providers was negotiated and agreed upon before the intervention, but they considered it later as still not sufficient to provide MH consultations to all referred beneficiaries. Professionally, non-specialized healthcare providers lacked incentive in the form of professional advancement. Those beneficiaries who received the first consultation were two times more likely to receive the second one (Table 6). Likely, six months allocated to MH consultations was not enough time to significantly increase their number. In Afghanistan, the number of consultations by non-specialized healthcare providers increased from 659 to well over 3,000 in a period of two years.15

Limitations

The major internal limiting factor of this intervention was the lack of a control group. Unfortunately, the results in the intervention group could not be compared with the status of those in the targeted areas who did not participate. Also, there were no formal instruments to determine face and content validity of the scales and tests employed. Another internal limiting factor was the pressure of time, constrained by the parameters scheduled for the INGO to deliver the intervention. Therefore, MH consultations by non-specialized healthcare providers started only during the six-month complementary project intervention after the main project’s one-year duration had ended. The interpretation of results was also limited. The results showed that the community-based MHPSS intervention improved well-being, decreased levels of distress and increased the resilience of the targeted population. However, it was not possible to single out the MHPSS activity which contributed most to these outcomes.35

The described program has been able to change the actual clinical practices of non-specialized healthcare providers only to a limited extent. This also limited the planned improvement of access to community MH services in targeted departments. Training is just one of the factors required for sustainable changes in MH practices of non-specialized healthcare providers. Other factors required are: successful cooperation with government; administrative policies promoting the integration of MH care into general health services; motivated and incentivized non-specialized healthcare providers and MH care professionals ready to develop community MH services; and supervision of non-specialized healthcare providers by MH professionals.40 The relative lack of these factors in Haiti presented external limitations for portions of this intervention. Technical support from expatriate specialists on a full time basis would better ensure the necessary guidance for Cordaid's MHPSS team, inexperienced with such projects.35 MH Coordinators on the ground are crucial in steering MH programs around the many challenges of integrating mental health care into general healthcare.40 A lack of practical in-service training for non-specialized healthcare providers was also a limiting factor for this intervention. MH trainings in other countries showed the importance of in-service training.38,39 Practice-oriented MH trainings for non-specialized healthcare providers and ongoing clinical supervision in the basic healthcare system also lead to increased demand for and access to MH services.15 The Shared Care Model, in which joint consultations are held between non-specialized healthcare providers and MH specialists, is a recommended means of providing ongoing training and support.40 In Haiti, the shortage of psychiatrists22 was a serious external limiting factor for implementing a Shared Care Model.

Strengths

This study presented a variety of outcome indicators, and therefore, to the best of our knowledge, it is the most detailed description of a community-based integrated MHPSS intervention in Haiti, post-earthquake. There are other descriptions of similar types of interventions in Haiti post-earthquake, but those have a shortage of outcome data.8,34 Cordaid’s MHPSS intervention was evidence-based and it used a unique monitoring and evaluation system, based on targets and indicators set in the inception phase.35 Outcomes including: improvement of well-being and resilience, stress reduction, and improvement of MHPSS knowledge of providers; were properly addressed in the framework of the project proposal.29 One limitation of many MHPSS projects worldwide is a lack of outcome indicators that measure impact on actual life circumstances of beneficiaries.11 Cordaid’s MHPSS program contributed to the demystification of mental health/psychosocial problems and related interventions in Haiti.35 Beneficiaries in five out of 10 departments of Haiti were able to receive scientific explanations and evidence-based intervention for their MH problems/ disorders; rather than treatment by traditional practitioners that might be based on mysticism, tradition and individual experiences. Cordaid’s intervention contributed to more open access to MH care by integrating that care into general healthcare; as WHO has recommended.40 This was the first documented program in Haiti to offer a comprehensive longitudinal training of non-specialized healthcare providers using the mhGAP Intervention Guide of the World Health Organization.31 Many other NGOs implemented MHPSS trainings in Haiti;8,28,36 but they used a narrower scope and did not employ the mhGAP Intervention Guide. The Cordaid's training intervention took into consideration immediate emergency MHPSS needs and the longer-term objective of improving MH services in a resource-poor developing country, post-disaster. The entire intervention was in tune with recommendations of local MH professionals who were supportive of the training of community psychosocial workers and non-specialized healthcare professionals. These local MH professionals also supported the plan to address access to community-based MH care and psychosocial support services.41,42 Given the technical support of the WHO, the Haitian MPHP also approved of the training of non-specialized healthcare providers in basic MH care and the enhancement of access to MHPSS at the level of primary health care.17 The approach of Cordaid was consistent with other relevant international recommendations on provision of MHPSS in emergency settings.1,2,10

The MHPSS intervention was shown to be culturally competent and acceptable to community stakeholders as indicated by the high level of community engagement throughout the program. The high level of engagement in this intervention is best evidenced by the participation of more than 100,000 direct beneficiaries, located in 5 of the 10 departments of Haiti. This level of local support is important because community stakeholders can play a critical role in achieving better outcomes in the field of MH care and psychosocial well-being.15

Recommendations and future perspectives

This study from Haiti shows that even within a fragile and resource-poor context, post-disaster, it is possible to improve access to MH care and psychosocial support services over a relatively short period of time. Further evidence-based studies of community level integrated MHPSS interventions in resource-poor, disaster-mediated settings are recommended. Future research might focus not only on output indicators quantified by intervention (e.g., trainings delivered, beneficiaries participating); but also on outcome indicators that measure impacts on quality of life (e.g., well-being, resilience, ability to function in daily life). Therefore, it is necessary to develop standardized tools to measure outcomes for MHPSS interventions.11

It is also important for future research to address the feasibility and quality of various MHPSS interventions in different countries, especially post-disaster. Each country has its specific economic, political and cultural context, and its people have a specific collective memory and mentality which can affect program implementation. For example, Bijoux mentioned a prevailing individualism impacting the provision of MH care services in Haiti.23 One measure of quality of a delivered MHPSS intervention is to determine if scarce resources are used in an efficient and effective way.12 Improvement of MH care and psychosocial support services should follow the WHO Six Building Block approach for strengthening the health system of a country.43 Although disasters can provide an opportunity for improving access to MH care and psychosocial support services;12 the rapid increase in service delivery that is often valued and typical in post-disaster situations may not be sustainable in the longer-term.15 Also it is important to assure that local governments and NGOs meet their contractual obligations;14,28 and their activities should be properly and frequently monitored.28 Financial sustainability of gains achieved through post-disaster MHPSS interventions remains problematic.14 The inclusion of well-defined MHPSS interventions in the Basic Package of Health Services of a country is recommended to improve sustainability of MHPSS interventions that have begun during an emergency period.15 More sustainable progress can be achieved by use of cyclical, long-term MHPSS interventions by foreign and local MH players.14,15 Best results can likely be achieved if local players gradually assume full responsibility for the development of enhanced MH services, using a strategic approach that is consistent throughout the region.16,44

Conclusions

This prospective, semi-quantitative study has demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of one community-based integrated MHPSS intervention in one resource-poor developing country, post-disaster. The training of community psychosocial workers was a more successful quality improvement intervention than the training of non-specialized healthcare providers. This community-based MHPSS intervention resulted in improved well-being, improved resilience and reduced distress in beneficiaries, but it is difficult to single out the particular MHPSS activities which were helpful to beneficiaries. The comprehensive intervention has potential to be reproduced in other resource poor settings and / or post-disaster environments, especially in developing countries where MH services may have been neglected over time. Close attention should be placed on the design of an intervention, so that the local cultural context and population specific features set the stage for a successful program.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to following donors for providing funding for mental health/psychosocial programming in Haiti: The European Commission’s Humanitarian Aid department (ECHO), Cordaid under grant No. 104299, and Cordaid and Trocaire under grant No. 103063.

References

- 1.van Ommeren M, Saxena S, Saraceno B. . Mental and social health during and after acute emergencies: emerging consensus?. Bull World Health Organ 2005; 83:71 - 5, discussion 75-6; PMID: 15682252 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Sphere Project. Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in humanitarian response, 2011. Available at: http://www.spherehandbook.org/. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 3.Williamson J, Robinson M. . Psychosocial interventions, or integrated programming for well-being. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2006; 4:4 - 25 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajkumar AP, Premkumar TS, Tharyan P. . Coping with the Asian tsunami: perspectives from Tamil Nadu, India on the determinants of resilience in the face of adversity. Soc Sci Med 2008; 67:844 - 53; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.014; PMID: 18562066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Komesaroff PA, Sundram S. Challenges of post-tsunami reconstruction in Sri Lanka: health care aid and the Health Alliance. Medical journal of Australia, 2006; 184 (1): 23-26. Available at: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2006/184/1/challenges-post-tsunami- reconstruction-sri-lanka-health-care-aid-and-health. Accessed 17 November 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Richters A, Dekker C, Scholte FW. . Community based sociotherapy in Byumba, Rwanda. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2008; 6:100 - 16; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/WTF.0b013e328307ed33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholte WF, Verduin F, Kamperman AM, Rutayisire T, Zwinderman AH, Stronks K. . The effect on mental health of a large scale psychosocial intervention for survivors of mass violence: a quasi-experimental study in Rwanda. PLoS One 2011; 6:e21819; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0021819; PMID: 21857908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose N, Hughes P, Ali S, Jones L. . Integrating mental health into primary health care settings after an emergency: lessons from Haiti. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2011; 9:211 - 24 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahoney J, Chandra V, Gambheera H, De Silva T, Suveendran T. . Responding to the mental health and psychosocial needs of the people of Sri Lanka in disasters. Int Rev Psychiatry 2006; 18:593 - 7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/09540260601129206; PMID: 17162703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). IASC Guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. IASC, 2007. Available at: http://www.humanitarianinfo.org/iasc/pageloader.aspx?page=content-subsidi-tf_mhps-default. Accessed 15 November 2013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Perez-Salez P, Liria AF, Baingana F, Ventevogel P. . Integrating mental health into existing systems of care during and after complex humanitarian emergencies. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2011; 9:345 - 57 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, Sridhar D, Underhill C. . Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2007; 370:1164 - 74; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X; PMID: 17804061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones LM, Ghani HA, Mohanraj A, Morrison S, Smith P, Stube D, Asare J. . Crisis into opportunity: setting up community mental health services in post-tsunami Aceh. Asia Pac J Public Health 2007; 19:60 - 8; PMID: 18277530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ventevogel P, Ndayisaba H, van de Put W. . Psychosocial assistance and decentralized mental health care in post conflict Burundi 2000-2008. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2011; 9:315 - 31 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ventevogel P, van de Put W, Faiz H, van Mierlo B, Siddiqi M, Komproe IH. . Improving access to mental health care and psychosocial support within a fragile context: a case study from Afghanistan. PLoS Med 2012; 9:e1001225; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001225; PMID: 22666183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budosan B, Jones L, Wickramasinghe WAL, Farook AL, Edirisooriya V, Abeywardena G, Nowfel MJ. After the wave: A pilot project to develop mental health services in Ampara district, Sri Lanka, post-tsunami. Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, 2008. Available at: http://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/53. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 17.Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Earthquake in Haiti – one year later. Report on the health situation, 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/hac/crises/hti/haiti_paho_jan2011_eng.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 18.Benjamin R. Violence conjugale en Haiti: Un defi a relever. Revue haïtienne de santé mentale, 2010; (1):125-138. Available at: http://www.haitisantementale.ca/pdf/violence.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 19.Clouin L. Pratique de soin et santé mentale en Haiti: Rapport d’evaluation, 2009. Available at: http://mhpss.net/wp-content/uploads/group-documents/83/1305808729-Eval_MH-CP_05-2009_Hati-1.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 20.World Health Organization-Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. Mental health atlas – Haiti, 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles/en/index.html. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 21.World Health Organization - Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse. Mental health atlas – Dominican Republic, 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/atlas/profiles/en/index.html. Accessed 15 November 2013

- 22.World Health Organization. Culture and mental health in Haiti: A Literature Review, 2010. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/emergencies/culture_mental_health_haiti_eng.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2013

- 23.Bijoux L. Évolution des conceptions et de l’intervention en santé mentale en Haïti. Revue haïtienne de santé mentale, 2010; (1):83-90. Available at: http://www.haitisantementale.ca/pdf/conceptionpdf. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 24.Caron J. Quelques réflexions sur la situation actuelle d’Haïti, la prévention des maladies mentales et la promotion de la santé mentale de sa population. Revue haïtienne de santé mentale 2010; (2): 107-134. Available at: http://www.haitisantementale.ca/article.php3?id_article=108&id_rubrique=14. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 25.International Organization for Migration (IOM). Assessment of the psychosocial needs of Haitians affected by the January 2010 Earthquake. IOM - Port au Prince, 2010. Available at: http://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/shared/shared/mainsite/activities/health/mental-health/Assessment-Psychosocial-Needs-Haitians-Affected-by-January-2010-Earthquake.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 26.Insitut Haitien de Statistique et D'Informatique (IHSI). Population totale, population de 18 ans et plus, menages et densites estimes en 2009, March, 2009. Available at: http://ihsi.ht/pdf/projection/POPTOTAL&MENAGDENS_ESTIM2009.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 27.Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The world fact book- Haiti, 2013. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ha.html. Accessed 15 November 2013

- 28.Budosan B, Bruno RF. . Strategy for providing integrated mental health / psychosocial support in post-earthquake Haiti. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2011; 9:225 - 36 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordaid. Project proposals and final reports on community-based integrated MHPSS programming in Haiti, 2011 and 2012. INGO Cordaid, The Hague, The Netherlands.

- 30.World Health Organization- Pakistan. Mental health module for psychosocial care givers. In Training Manual for District and PHC Physicians, 2005. WHO - Islamabad, Pakistan. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings, 2010. Available at: www.who.int/mental_health/mhgap. Accessed 15 November 2013. [PubMed]

- 32.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. . A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24:385 - 96; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2307/2136404; PMID: 6668417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gail MW, Young HM. The 14-item resilience scale, 1987 Available at: http://www.resiliencescale.com/en/rstest/rstest_14_en.html. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 34.Schinina G, Aboul HM, Ataya A, Dieuveut K, Marie-Ade'le S. . Psychosocial response to the Haiti earthquake: the experiences of International Organization for Migration. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2010; 8:158 - 64; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1097/WTF.0b013e32833c2f78 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kortmann G, Mathurin E, Henrys K. Final Evaluation of the MHPS program of Cordaid in Haiti, 2010-2011. Public Health Consultants, 2011. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lecomte Y. La santé mentale en Haiti: le nouvel eldorado? Revue haitienne de santé mentale, 2010; (2). Available at: http://www.haitisantementale.ca/revue_n2/n2art1.pdf Accessed November 17 2013.

- 37.Kutcher S, Chehil S, Roberts T. . An integrated program to train local health care providers to meet post-disaster mental health needs. Rev Panam Salud Publica/Pan. Am J Public Health 2005; 18:338 - 45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Budosan B, Jones L. Evaluation of effectiveness of mental health training program for primary health care staff in Hambantota district, Sri Lanka, post-tsunami. Journal of Humanitarian Assistance, 2009. Available at: http://sites.tufts.edu/jha/archives/509. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 39.Hijazi Z, Weissbecker I, Chammay R. . The integration of mental health into primary health care in Lebanon. Intervention (Amstelveen) 2011; 9:265 - 78 [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. Integrating mental health into primary care: A global perspective, 2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/Integratingmhintoprimarycare2008_lastversion.pdf; Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 41.Lecomte Y, Raphael F. Les modèles d’intervention dans une politique de santé mentale en Haïti. Revue haïtienne de santé mentale, 2010; (2):13-30. Available at: http://www.haitisantementale.ca/article.php3?id_article=108&id_rubrique=14. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 42.Raphael F. Réflexions sur la santé mentale dans une nouvelle Haïti. Revue haïtienne de santé mentale, 2010; (1): 157-165. Available at: http://www.haitisantementale.ca/pdf/reflexion.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 43.World Health Organization. Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO's Framework for Action, 2007. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf. Accessed 15 November 2013.

- 44.Vijoy V. Development of trained manpower for mental health services in South Asia. Paper presented at 3rd International Conference of South Asian Federation of Psychiatric Associations, 2007. Kaluthara, Sri Lanka.