Abstract

Trauma signature (TSIG) analysis is an evidence-based method that examines the interrelationship between population exposure to a disaster, extreme event, or complex emergency, and the inter-related physical and psychological consequences for the purpose of providing timely, actionable guidance for effective mental health and psychosocial support that is organically tailored and targeted to the defining features of the event.

A series of TSIG case studies has been published since 2011 and TSIG analyses of recent disasters are in process. Disaster Health intends to expedite and feature novel TSIG research focusing on late-breaking disaster events.

At the current stage of development, expert consensus is sought for refining the TSIG methodology using a Delphi process. The overarching goal is to create a fully operational system to provide timely guidance for adapting disaster behavioral health support to the salient psychological risk factors in each disaster.

Keywords: trauma signature analysis, TSIG, mental health, psychosocial, disaster response

Introduction and Rationale for Trauma Signature (TSIG) Analysis

Each disaster leaves an imprint on the affected population, a singular “signature.” A critical unmet need in the field of disaster mental/behavioral health is the capability to tailor mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) to the unique constellation of psychological risk factors operating within each disaster event. We have developed and introduced Trauma Signature (TSIG) analysis to the fields of disaster mental/behavioral health and disaster public health in response to this identified need.1-6 We define TSIG analysis in the following manner:

Trauma signature (TSIG) analysis is an evidence-based method that examines the interrelationship between population exposure to a disaster, extreme event, or complex emergency and the interrelated physical and psychological consequences for the purpose of providing timely, actionable guidance for effective mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS)—or disaster behavioral health (DBH)* support—that is organically tailored and targeted to the defining features of the event.

According to Shultz et al. 2013 (in press),3 “TSIG examines the extent to which disaster survivors were exposed to empirically-documented risk factors for psychological distress and mental health disorders. Grounded on the Disaster Ecology Model, TSIG is premised on the assumption that each disaster exposes the affected population to a novel pattern of traumatizing hazards, loss, and change. This singular “signature” of exposure risks is a predictor (or series of predictors) of the psychosocial and mental health consequences. Disaster-specific analysis is important because, as Kessler and team have documented across a spectrum of international disasters, “secondary stressors unique to a particular disaster situation have more impact than the disasters themselves” in determining the prevalence of post-disaster mental disorders.”7

Too frequently, MHPSS response to disasters is unguided, uncoordinated, and unscientific. For example, in our TSIG analysis of the 2010 Haiti earthquake1,8 it was evident that MHPSS was never prioritized. The disaster behavioral health response that was cobbled together in Haiti evidenced many serious deficits (Table 1) including: self-deployment and arrival on-scene of many uninvited personnel, lack of coordination among response teams, provision of non-evidence-informed services loosely labeled as “psychosocial,” provision of services such as critical incident stress debriefing (CISD) that are known to be ineffective and potentially harmful for survivors, provision of services that were not culturally-adapted or language-appropriate for Haiti, premature cessation of many services, and minimal or no program evaluation. From the perspective of responders, there was a lack of pre-deployment guidance about the specific stressors that would be encountered, and lack of on-scene psychological support, leading to high rates of traumatization among response personnel.

Table 1. Prevailing challenges and deficits in mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS).

| Mass convergence of responders to the disaster scene |

| Failure to prepare responders for the event-specific psychological stressors they will encounter |

| Provision of non-evidence-based “psychosocial” programs to disaster survivors |

| Failure to target programs for survivors to the event-specific psychological risks |

| Failure to conduct on-scene disaster mental/behavioral health needs assessments |

| Failure to identify persons at high risk for psychological impairment and psychopathology |

| Lack of disaster mental/behavioral health services maintained throughout recovery |

| Absence of ongoing monitoring of survivor mental/behavioral health status |

| Failure to evaluate MHPSS intervention effectiveness and efficacy |

Haiti is not a “one-off” instance of deficient MHPSS response. What occurred in Haiti reflects pervasive and prevailing challenges (Table 1). Fortunately these serious limitations can and should be swiftly redressed. Risk factors for disaster-related psychological distress and impairment have been documented empirically. Disaster-specific risk factors can be identified from disaster situation reports issued in the early aftermath allowing MHPSS response to be tailored and timed to the defining features of the event. It is time to infuse science into MHPSS response; we need evidence-based support and intervention. TSIG analysis can make an important contribution.

TSIG Analysis in the Context of Evidence-Based MHPSS Disaster Response

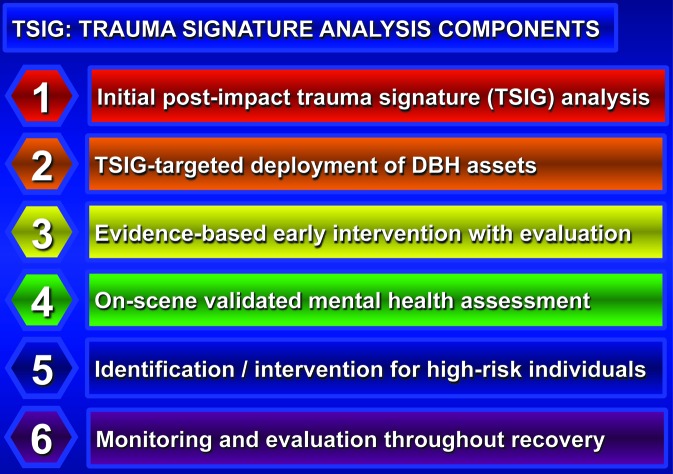

Optimal MHPSS response1,2 that incorporates TSIG analysis can be summarized as a sequence of six steps (see also Figure 1): 1) initial TSIG analysis to guide response based on the defining features of the disaster or potentially-traumatizing event (PTE), 2) TSIG-guided preparation of responders for what to expect and deployment of appropriate response assets, 3) delivery and evaluation of evidence-informed early interventions, 4) implementation of onsite validated disaster behavioral health needs assessment, 5) identification and intervention with individuals at high risk for disaster-related psychological distress, impairment, or psychopathology, and 6) continuous monitoring of responder and survivor mental health throughout recovery with comprehensive (“end-to-end”) evaluation of the MHPSS response.

Figure 1. Optimal mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS): Six sequential steps

While the components that are uniquely contributed by TSIG analysis are primarily incorporated into steps 1 and 2, in order to achieve optimal MHPSS response, significant quality improvement is needed and desirable for steps 3–6.

An electronic appendix, entitled “Operationalizing TSIG” (www.landesbioscience.com/journals/disasterhealth/CommArt-Sup.pdf) provides details for each of the six steps in the categories of description, rationale, operationalization, unmet needs, research questions, and opportunities.9

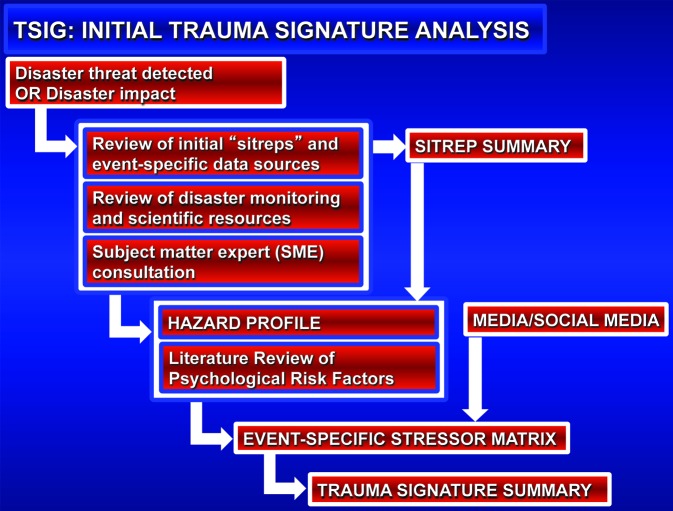

Framework for the Initial TSIG Analysis

The initial TSIG analysis is the first step of six that comprise an optimal evidence-based MHPSS response (summarized in Figure 1). As illustrated in Figure 2, Initial TSIG analysis consists of these elements: 1) characterization of the affected communities (geographic scope, numbers affected, demographics); 2) real-time collection and synthesis of information from disaster situation reports (“sitreps”) issued regularly in the early days and weeks post-impact; 3) identification and data collection from disaster monitoring and scientific resources specific to the disaster event (e.g., United States Geological Survey (USGS) earthquake data on the Haiti earthquake, National Hurricane Center (NHC) data on Superstorm Sandy); 4) consultation with disaster sciences subject matter experts (e.g., USGS geophysicists for Haiti earthquake, NHC meteorologists for Superstorm Sandy); 5) construction of a hazard profile based on open-source data developed in the preceding steps; 6) review and integration of the scientific literature on evidence-based risk factors for psychological distress and psychopathology for persons exposed to the event-specific hazards; 7) incorporation of information on disaster stressors identified anecdotally in media and social media accounts of the event; 8) creation of an event-specific stressor/risk factor matrix that is cross-referenced with the evidence-based literature (stressors are enumerated by disaster phase within the categories of exposure to hazard, loss, and change), ccounts, cross-referenced with the evidence-based literature; and 9) generation of a TSIG summary for the disaster based on the estimated psychological severity of exposures to hazards, loss, and change.

Figure 2. Initial post-impact trauma signature analysis

Several key points in this process require more explanation. Initial TSIG analysis is triggered when a disaster alert or warning is issued, or when disaster strikes without warning. Local disaster response is activated immediately and higher-level response (regional, national, international) is brought into play as needed depending upon the scale of the event. For major events, publicly-accessible disaster situation reports (sitreps) are generated and hosted on websites such as the Global Disaster Alert and Coordination System (GDACS), United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Assistance, and ReliefWeb within the early hours or days,

Hazard profile. To create the hazard profile that provides a scientifically-sound description of the event, TSIG begins with review of disaster data including sitreps from governmental and NGO agencies and available data from disaster monitoring and scientific resources. Subject matter experts (SMEs) may be contacted to assure that the event is correctly described from a disaster sciences perspective. This step describes the physical forces of harm that impact the human population in harm’s way in order to characterize “exposure to hazard.” Disaster epidemiologic data are also collected on numbers of deaths, injuries, displaced, affected.

Psychological risk factor/stressor matrix. The next step involves matching the scientific event description to the ever-expanding literature on psychological risk factors (for distress, disorder, and psychiatric diagnosis). This is summarized in a “stressor matrix”: risk factors are arrayed by disaster phase for categories of exposure to hazard, loss, and change. News media and social media feeds may also be incorporated at this stage to enrich the list of stressors.

Trauma signature summary. The final step in the initial TSIG analysis involves the construction of a summary table of salient psychological risk factors, grouped into categories of exposure to hazard, loss, and change with an estimate of the “exposure severity” for each risk factor.

TSIG Case Studies

To demonstrate the feasibility of conducting TSIG analysis, we developed a series of disaster case studies, beginning with post hoc analyses of historical disasters and progressing to real-time analyses of unfolding events. Our first TSIG case study was performed on data from the 2010 Haiti earthquake which we described as “a potent example of the rare catastrophic event where all major risk factors for psychological distress and impairment are prominent and compounding.”1

Our TSIG case studies have been wide-ranging, including examples of natural, human-generated, and hybrid disasters, and complex emergencies.1-6,8,10-17 In addition to TSIG analyses for the 2010 Haiti earthquake,1,8,10 we performed analyses on other natural disaster events including the 2011 US, Super Tornado Outbreak,11 2009 and 2011 river floods in the Upper Midwest,4,12,13 and 2012 Superstorm Sandy.5,6 In the realm of hybrid (interacting natural and human-generated components), we carefully analyzed the 2011 Great East Japan Disaster.3,14 The 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill provided an application of TSIG for an anthropogenic (human-generated) event.10 In the realm of complex emergencies/humanitarian crises, we have examined patterns of internal displacement in Colombia15,16 and the Russia-Georgia conflict in South Ossetia.17

With each case study, the research literature database of evidence-based research studies is expanded. The case studies have provided an open invitation for colleagues with interest in a particular disaster event to join with us both in authorship and in advancing the TSIG methodology. TSIG developers and co-authors have presented a series of invited papers, workshops, and institutes to introduce the methodology and actively seek feedback. These forums have included an open invitation to join us in collaboration.18-28 Currently, an international cadre of co-authors and co-developers spans five continents.

Ongoing Development and Refinement of the TSIG Model

Development, refinement, and validation of the TSIG approach is accelerating. We are actively seeking opportunities to automate and operationalize TSIG. This will ultimately require database capabilities and a dedicated staff. However, at present we are soliciting additional disaster case studies, consulting with subject matter experts, creating the structure for the literature database, and launching an Internet-based Delphi process in 2013 to develop expert consensus regarding the methodology. We will then seek opportunities to partner with lead response agencies in real-world, real-time applications of the TSIG process. Once refined, our intention is to develop a practical system that can help infuse evidence-based science into the decision-making process for matching MHPSS response to the defining features of the disaster event. TSIG is designed to contribute to the creation of MHPSS response that increasingly approaches the attributes of optimal response outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Attributes of optimal response for mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS).

|

Response teams invited and official permission granted Ideally there will be a “gatekeeper” function in place to deny unauthorized access to the scene by groups that self-elect to deploy. |

|

Response teams composed of asset-typed, credentialed personnel This assures that persons who come to the scene have been appropriately trained and vetted including background checks. Personnel on-scene should have a clear job description and defined reporting lines. |

|

Responder units arrive fully equipped and self-sustaining Responders should create a “light footprint” on the scene, bringing value added while not usurping scarce resources. |

|

Responders trained in disaster survival skills Responders should be able to function in austere post-disaster environments to minimize the likelihood of injury or illness that will create a burden on the team and the limited health services capacity and capabilities following disaster. |

|

Responders thoroughly briefed on the nature of the event Responders should arrive prepared to address the specific event, bringing the right tools and personnel. |

|

Responders prepared psychologically for the specific event Responders should know the specific psychological stressors they will encounter, verify their readiness to respond given knowledge of the on-scene environment, receive briefing on coping strategies, and bring psychosocial support personnel and resources for the team. |

| Responders provide their specialized services in a manner that optimizes survivor safety, calming, connectedness, self- and community efficacy, and instills hope |

|

Response tailored to enhance resilience of the affected community When possible and appropriate, responders should actively engage the survivors in the response and recovery process to increase individual and community efficacy and to foster resilience. |

|

Response documented, evaluated, critiqued with full accountability Response actions and activities should be carefully logged, evaluated, assessed for effectiveness, and critiqued to determine strengths and weaknesses of the response. Such an after action review should include plans for redressing failures of response and for ongoing quality improvement. Constructive feedback, practical training/retraining, and necessary operational modifications should be implemented in a timely manner. |

Supplementary Material

Submitted

02/14/13

Accepted

02/14/13

Footnotes

disaster behavioral health (DBH) support - preferred US terminology

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- 1.Shultz JM, Marcelin LH, Madanes SB, Espinel Z, Neria Y. . The “Trauma Signature:” understanding the psychological consequences of the 2010 Haiti earthquake. Prehosp Disaster Med 2011; 26:353 - 66; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S1049023X11006716; PMID: 22336183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shultz JM, Kelly F, Forbes D, Verdeli H, Leon GR, Rosen A, et al. . Triple threat trauma: evidence-based mental health response for the 2011 Japan disaster. Prehosp Disaster Med 2011; 26:141 - 5; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S1049023X11006364; PMID: 22107762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shultz JM, Forbes D, Wald D, Kelly F, Solo-Gabriele HM, Rosen A, et al. . Trauma signature of the Great East Japan Disaster provides guidance for the psychological consequences of the affected population. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013; In press http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/dmp.2013.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shultz JM, McLean A, Herberman Mash HB, Rosen A, Kelly F, Solo-Gabriele HM. . Youngs Jr. GA, Jensen J, Bernal O, Neria Y. Mitigating flood exposure: Reducing disaster risk and trauma signature. Disaster Health 2013; 1; In press http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/dish.23076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shultz JM, Neria Y. The Trauma Signature of Hurricane Sandy: A Meterological Chimera. Online at: The 2x2 Project, Columbia University, Mailman School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology. Published 14 November 2012. Available at: http://the2x2project.org/the-trauma-signature-of-hurricane-sandy/

- 6.Shultz JM, Walsh L, Neria Y. . Meteorological Chimera: Examining the Trauma Signature of Superstorm Sandy. Disaster Health 2013; 1 In press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Petukhova M, Hill ED, WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. . The importance of secondary trauma exposure for post-disaster mental disorder. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2012; 21:35 - 45; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S2045796011000758; PMID: 22670411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shultz JM, Marcelin LH, Espinel Z, Madanes SB, Allen A, Neria YA. Haiti Earthquake 2010: Psychosocial Impacts. In: Bobrowsky, P. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Natural Hazards. Dordrecht, Heidelberg, London, New York: Springer Publishing, 2013 (in press). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shultz JM. Whitepaper: Operationalizing TSIG. Available on the Disaster Health website at: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/disasterhealth/CommArt-Sup.pdf.

- 10.Shultz JM, Neria Y, Espinel Z, Marcelin LH, Madanes S. Trauma Signature Analysis: Rapid Post-Impact / Pre-Deployment Guidance for Mental Health Response. Presented at: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) 26th Annual Meeting (Panel: Global Perspectives in Planning for, Responding to, and Recovering From Disaster), Le Centre Sheraton Montreal Hotel, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 5 November 2010.

- 11.Shultz JM, Herberman Mash HB, Rosen A, Espinel Z, Kelly F, Neria Y. The Trauma Signature of the 2011 U.S. Super Tornado Outbreak. Presented at: 2nd International Preparedness and Response to Emergencies and Disasters (IPRED II) Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 16/17 January 2012. IPRED II Abstract Book, p. 240.

- 12.McLean AJ, Shultz JM. . Flood Disaster Averted: Red River Resilience. Presented at: 17th World Congress on Disaster & Emergency Medicine, Beijing, China, 3 June 2011. Prehosp Disaster Med 2011; 26:Suppl. 1 s139; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S1049023X1100433X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shultz JM, McLean AJ, Rosen A, Youngs GA, Jensen J, Neria Y. A Tale of Two Cities: Flooding and Effects on Community Resilience (Poster). Presented at: 2nd International Preparedness and Response to Emergencies and Disasters (IPRED II) Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 16/17 January 2012. IPRED II Abstract Book, p. 253.

- 14.Shultz JM, Espinel Z, Kelly F, Neria Y. Examining the Trauma Signature of the Japan Tsunami/Nuclear Crisis. Presented at: Social Bonds and Trauma Through the Life Span: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) 27th Annual Meeting, Baltimore Marriott Waterfront Hotel, Baltimore, MD, 4 November 2011.

- 15.Espinel Z, Shultz JM, Ordonez A, Neria Y. Colombia’s Internally Displaced Persons: The Trauma Signature. Presented at: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) 28th Annual Meeting, J.W. Marriott Los Angeles at L.A. LIVE, Los Angeles, CA, 2 November 2012.

- 16.Shultz JM, Bueno Ramirez AM, Espinel Z. Posada Villa JA. Herberman Mash HB, McCoy CB, Neria Y. Displaced within Borders: Colombia’s Humanitarian Crisis. Presented at: 2nd International Preparedness and Response to Emergencies and Disasters (IPRED II) Conference, Tel Aviv, Israel, 16/17 January 2012. IPRED II Abstract Book, p. 236.

- 17.Migline V, Shultz JM. . Psychosocial Impact of the Russian Invasion of Georgia in 2008. Presented at: 17th World Congress on Disaster & Emergency Medicine, Beijing, China, 1 June 2011. Prehosp Disaster Med 2011; 26:Suppl. 1 s110; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1017/S1049023X11003438 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shultz JM, Neria Y, Espinel Z, Kelly F. Trauma Signature Analysis: Evidence-Based Guidance for Disaster Mental Health Response. Presented at: 17th World Congress on Disaster & Emergency Medicine, Beijing, China, 31 May 2011.

- 19.Shultz JM, Kelly F, Espinel Z, Neria Y. Rapid Evidence-Based Guidance for Post-Impact Disaster Mental Health Response: Trauma Signature (TSIG) Analysis. Presented at: Social Bonds and Trauma Through the Life Span: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) 27th Annual Meeting, Baltimore Marriott Waterfront Hotel, Baltimore, MD, 2 November 2011.

- 20.Shultz JM. . Trauma Signature Analysis. Presented at: Innovation and Results: Surviving the Times. The Joint Commission 2012 Accreditation Standards Update. Westin Lombard Yorktown Hotel. Lombard 2011; IL:60148 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shultz JM. Trauma Signature Analysis: Targeting Mental Health and Psychosocial Support to the Defining Features of the Disaster Event. Presented at: 21st Annual Surviving Trauma Conference, Hilton Pensacola Gulf Front Hotel, Pensacola Beach, Florida, 18 November 2011.

- 22.Shultz JM, Bernal O, Espinel Z. Trauma Signature (TSIG) Analysis: Science-Based Actionable Guidance for Disaster Mental Health Response. Presented at: XVIII International Congress of Group Psychotherapy and Group Processes, Cartagena, Colombia, 21 July, 2012.

- 23.Shultz JM. Targeting Disaster Behavioral Health Response to the Defining Features of the Disaster Event: The Trauma Signature. Presented at: International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) 28th Annual Meeting. Panel: Achieving Integration of Disaster Behavioral Health and Public Health: Practice, Analysis, Policy, and Planning. J.W. Marriott Los Angeles at L.A. LIVE, Los Angeles, CA, 2 November 2012.

- 24.Shultz JM. Trauma Signature Analysis: Guidance for Disaster Behavioral Health Response. Presented at: Telfer School of Managment Health Systems Research Seminar Series. University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 27 November 2012.

- 25.Shultz JM. Targeting Mental Health and Psychosocial Support to the Defining Features of the Disaster Event: The Trauma Signature. Presented at: EnRiCH International Network for Collaborative Practice & Community Engagement. Chateau Laurier Hotel, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, 29 November 2012.

- 26.Shultz JM. Mental Health Issues During a Large-Scale Disaster. Presented at: Hospital Disaster Planning, Preparations, and Response Symposium: An All-Hazards Approach. Jackson Memorial Hospital, Miami, FL, 15 February, 2013.

- 27.Shultz JM. Trauma Signature Analysis: Disaster Mental Health and Security During Extreme Events. Presented at: Health and Human Security. World-Wide Human Geography Data Working Group, Conference Center of the Americas, U.S. Southern Command, Doral, FL, 27 February 2013.

- 28.Shultz JM, Espinel Z. Environmental Variability and Trauma Signature Analysis: Psychological Dimensions of Disasters and Extreme Events Presented at: Environmenal Variability Considerations for Force Health Protection. USSOUTHCOM, DoD SME, and Partnering Nations LNO Roundtable Meeting, Conference Center of the Americas, U.S. Southern Command, Doral, FL, 12 March 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.