Summary

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles, remodeling and exchanging contents during cyclic fusion and fission. Genetic mutations of mitofusin (Mfn) 2 interrupt mitochondrial fusion and cause the untreatable neurodegenerative condition, Charcot Marie Tooth disease type 2A (CMT2A). It has not been possible to directly modulate mitochondrial fusion, in part because the structural basis of mitofusin function is incompletely understood. Here we show that mitofusins adopt either a fusion-constrained or fusion-permissive molecular conformation directed by specific intramolecular binding interactions, and demonstrate that mitofusin-dependent mitochondrial fusion can be regulated by targeting these conformational transitions. Based on this model we engineered a cell-permeant minipeptide to destabilize fusion-constrained mitofusin and promote the fusion-permissive conformation, reversing mitochondrial abnormalities in cultured fibroblasts and neurons harboring CMT2A gene defects. The relationship between mitofusin conformational plasticity and mitochondrial dynamism uncovers a central mechanism regulating mitochondrial fusion whose manipulation can correct mitochondrial pathology triggered by defective or imbalanced mitochondrial dynamics.

Mitochondria fuse to transfer genetic information and promote mutual repair through content exchange. Mitochondrial outer membrane tethering and fusion mediated by mitofusins (Mfn) 1 and 2 is essential for embryonic development1–3and tissue homeostasis4–6. Multiple mutations that provoke Mfn2 dysfunction can cause the untreatable neurodegenerative condition, Charcot Marie Tooth disease type 2A (CMT2A)7. The obligate initial step in mitochondrial fusion is formation of mitochondria-mitochondria tethers. Mitofusins on different mitochondria undergo GTPase-independent trans-dimerization through anti-parallel binding of their extended carboxy terminal α-helical domains8. Conventional wisdom is that mitofusins exist constitutively in an “active” extended molecular conformation permissive for tethering, but specific contextual data on other possible structural determinants of mitofusin-mediated mitochondrial tethering are lacking. Here, based on domain similarity between human mitofusins and the prototypical dynamin superfamily protein bacterial dynamin-like protein (DLP)9 we posited that mitofusins can adopt a more folded molecular conformation. Such conformational plasticity might be experimentally and therapeutically manipulated to enhance or suppress mitochondrial tethering and subsequent tethering-dependent organelle fusion.

Conformational malleability of Mfn2

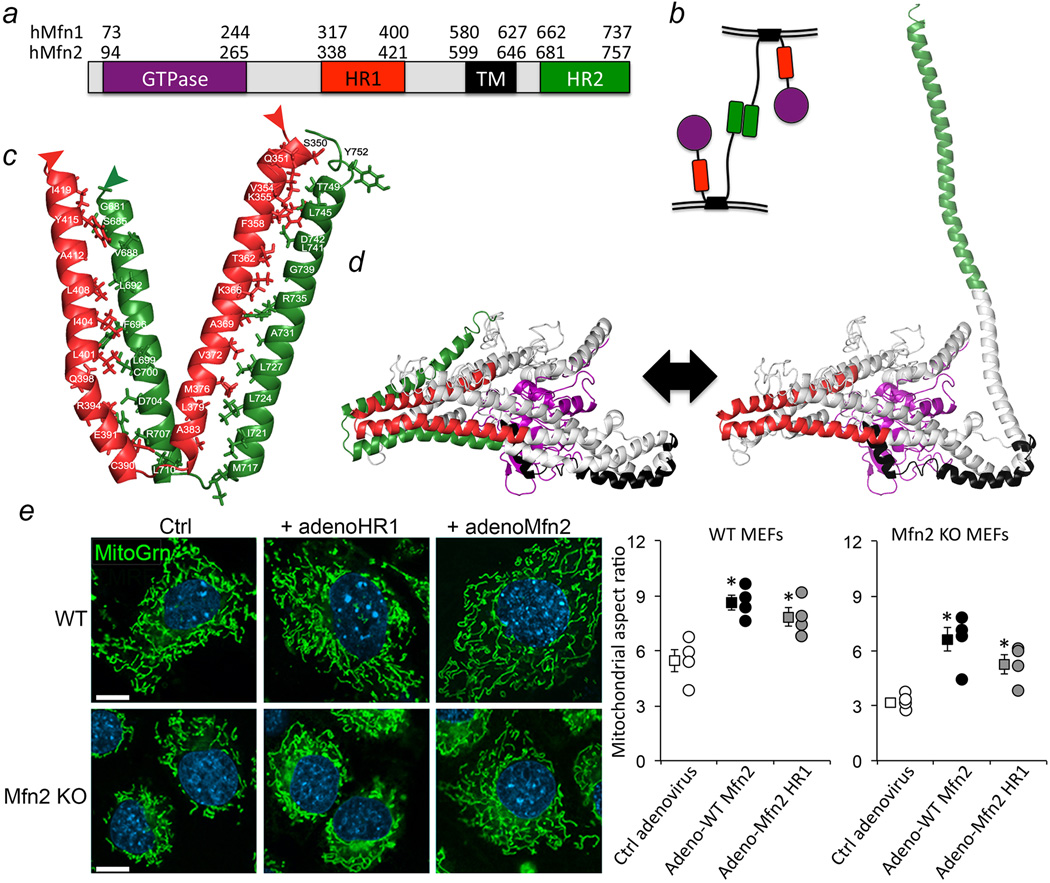

Mfn1 and Mfn2 share an amino terminal GTPase domain followed by a first coiled-coiled heptad repeat region (HR1), two adjacent small transmembrane domains, and a carboxyl terminal second coiled-coiled heptad repeat region (HR2) (Figure 1a). Amino acid conservation is highest in the GTPase, transmembrane and HR2 regions (Extended Data Figure. 1a). HR2 domains extending from Mfn molecules on different mitochondria dimerize to tether the molecules (Figure 1b)8. HR2 can also bind HR110. Using the crystal structure of bacterial DLP9 to model Mfn2 we refined identities of HR2 amino acids that mediate inter-molecular HR2-HR2 tethering8 (Extended Data Figure. 1b; Supplemental video 1). The DLP structure predicts that these same amino acids mediate intra-molecular antiparallel binding of HR2 to HR1 (Figure 1c; Extended Data Figure. 1c; Supplemental video 2). Local unfolding and bending of the HR1 α-helix at amino acids 384–387 (REQQ) contains it within the core Mfn2 globular structure, restraining HR2 that we predict bends at amino acids 712–715 (QEIA) (Figures 1c, 1d left; Supplemental video 3). This configuration would not be conducive for mitochondrial tethering, which requires cytosolic extension of HR2 (Figure 1d right; Supplemental video 4).

Figure 1. Intramolecular interactions between Mfn2 HR1 and HR2 modulate mitochondrial fusion.

a. Domain model of Mfn structure. GTPase is purple, HR1 is red, transmembrane (TM) domain is black, HR2 is green. Amino acid numbers are for human Mfn1 and Mfn2. b. Mfn-Mfn interacting in trans to produce mitochondrial tethering that precedes outer membrane fusion. c. Intra-molecular hMfn2 HR1 (red) - HR2 (green) interactions based on crystal structures of bacterial DLP. d. Homology model of hMfn2 showing putative constrained/inactive (left) and extended/active (right) conformations. e. Confocal images of MEFs expressing β-gal (Ctrl), hMfn2 HR1 fragment or fully functional wild-type (WT) hMfn2. MitoTracker Green (MitoGrn) stains mitochondria, blue Hoechst stains nuclei. Quantitative results are to the right. Group data are mean±SEM; *=P<0.05 vs Ctrl (ANOVA) in 4 independent experiments for each condition. Scale bars are 10 microns.

Manipulating fusion with HR1 minipeptides

We examined the functional import of intra-molecular Mfn2 HR1-HR2 binding by introducing into murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) a recombinant Mfn2 HR1 fragment containing the sequences predicted to mediate intra-molecular HR1-HR2 binding (adeno-HR1). Competition of intra-molecular HR1-HR2 interactions by free HR1 should unfold the protein, extend the terminal HR2 arm, and promote mitochondrial tethering/fusion. Indeed, adeno-HR1 increased mitochondrial aspect ratio (length/width, reflecting fusion) in both wild type (WT) and Mfn2 null11 MEFs (Figure 1e). Thus, conformational plasticity and reversible intra-molecular HR1-HR2 binding can be as important as inter-molecular HR2-HR2 binding for Mfn functioning.

To localize HR1-HR2 binding domains we used adenovirus to express minipeptides flanking the HR1 REQQ bend. We engineered into each minipeptide mutations substituting glycines (Gly, which increases flexibility in the secondary structure) or prolines (Pro, which breaks the α helix) for centrally positioned leucines (Leu). Adeno428-448 and its Gly- and Pro-substituted mutants did not affect mitochondrial fusion, whereas adeno367-384Gly and adeno398-418Gly consistently had opposing effects on mitochondrial morphology (Extended Data Figure. 2).

Adeno-HR1, adeno367-384Gly and adeno398-418Gly altered mitochondrial aspect ratio in MEFs expressing Mfn1 or Mfn2 in any combination, but not in MEFs completely lacking mitofusins (Extended Data Figure. 2a). Thus, Mfn2 HR1-derived minipeptides modulate mitochondrial fusion mediated by either Mfn1 or Mfn2. Adeno367-384Gly and adeno398-418Gly did not adversely impact mitochondrial polarization status (Extended Data Figure. 2b) or Parkin recruitment and mitophagy induced by mitochondrial uncoupling (Extended Data Figure. 2c), which are also impacted by mitofusins12,13.

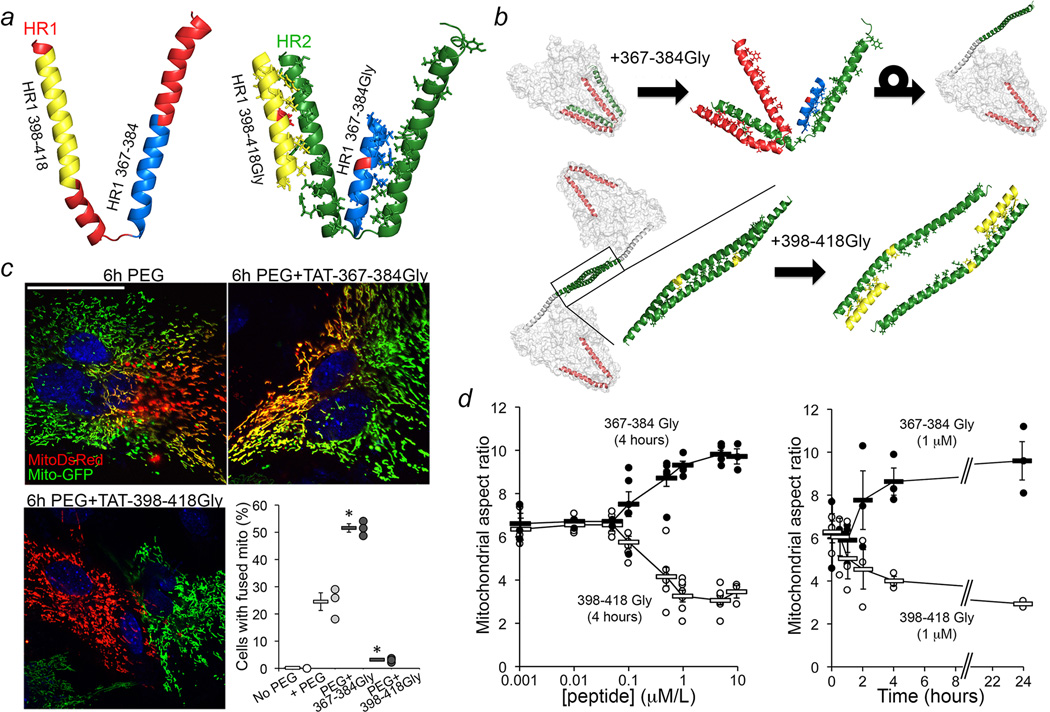

According to our Mfn2 molecular model, fusion-promoting 367-384Gly should bind amino acids 716–736 near the Mfn2 carboxyl-terminus (Figure 2a). Competition of intra-molecular HR1-HR2 binding here by the peptide would release HR2 from its HR1 anchor and permit it to unfold into a cytosol-extended conformation (Figure 2b). By contrast, fusion-suppressing 398-418Gly should bind HR2 at amino acids 682–701 (Figure 2a), thus interrupting HR2-HR2 interactions essential to trans Mfn-Mfn tethering (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Adenovirally-expressed Gly-substituted minipeptides derived from Mfn2 HR1 regulate Mfn-mediated mitochondrial fusion.

a. Derivation of HR1 minipeptides and their predicted binding to HR2. Red shows critical Gly substitution. b. Ribbon representations showing (top) TAT-367-384Gly (blue) interrupting intra-molecular HR1-HR2 binding, and (bottom) TAT-398-418Gly (yellow) interrupting the inter-molecular HR2-HR2 interaction essential to mitochondrial tethering. c. Mitochondrial content exchange (red-green overlay) 6h after PEG-mediated cell fusion. Scale bar is 20 µm. N=3 experiments measuring ~50 cells each; *=P<0.01 vs +PEG (ANOVA and Tukey’s test). d. TAT minipeptide dose-response at 4 hours (left, n=6 or 7) and time-course of 1 µM effects (right, n=3). Group data are mean±SEM.

We studied our minipeptides after synthesizing them as cell-permeant C-terminal TAT47–57 conjugates. Fusion-mediated mixing of mitochondrial contents14 was more than doubled by 1 µM TAT-367-384Gly for 6 hours, whereas 1 µM TAT-398-418Gly completely suppressed mitochondrial fusion (Figure 2c). Mitochondrial aspect ratio changed in parallel (Figure 2d), with EC50 values of 280±90 nM and 250±90 nM for TAT-367-384Gly and TAT-398-418Gly effects, respectively (Figure 2d; Extended Data Figure. 3a). Mitochondrial dynamics protein abundance (Extended Data Figure. 3b, 3c), Mfn2 GTPase activity (Extended Data Figure. 4a), and mitochondrial polarization and cell viability (Extended Data Figure. 4b) were unaffected by the minipeptides.

HR1 minipeptides alter Mfn2 conformation

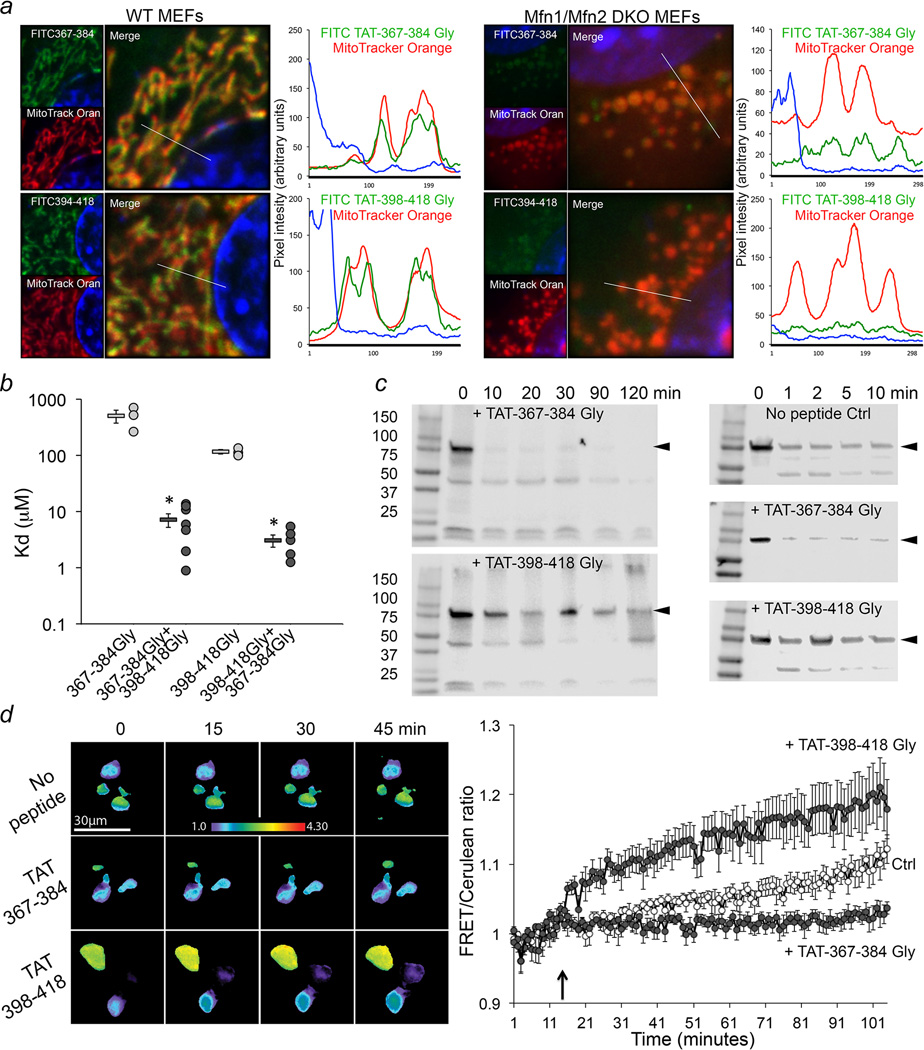

Additional studies validated the conformational shift mechanism of minipeptide action: FITC-labeled TAT-peptides decorated mitochondria in normal cells, but not cells lacking mitofusins (Mfn1/Mfn2 DKO MEFs) (Figure 3a). Binding of minipeptides to recombinant Mfn2 was positively cooperative (Figure 3b), consistent with destabilization of highly folded Mfn2 by 367-384Gly that facilitates 398-418Gly binding to newly extended carboxyl-terminal HR2 domains. We demonstrated that TAT-367-384Gly promoted Mfn2 HR2 unfolding and extension by showing that it accelerated carboxyl terminal-directed proteolytic digestion of Mfn2 (TAT-398-418Gly had the opposite effect) (Figure 3c). Finally, we determined that TAT-398-418Gly promotes a more folded Mfn2 conformation using Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) of hMfn2 tagged at the amino terminus with mCerulean1 and the carboxyl terminus with mVenus1 (Figure 3d). Collectively, the data in Figures 2 and 3 demonstrate that the effects of Mfn2 HR1-derived minipeptides on mitochondrial fusion derive from their ability to promote or suppress Mfn2 unfolding and HR2 extension.

Figure 3. Molecular effects of HR1-derived TAT-minipeptides on Mfn2.

a. Confocal localization of FITC-labeled TAT-minipeptides (green) in WT MEFs (left) and Mfn null MEFs (Mfn1/Mfn2 DKO; right). Red mitochondria were stained with MitoTracker Orange; blue is nucleus (Hoechst). Line-scans are to the right of their respective images. Representative of >20 images/group. Scale bars are 5 microns. b. Peptide binding to Mfn2. Group data are mean±SEM; n = 3 studies for baseline and 6 or 7 studies for cooperativity. * = P<0.05 vs same peptide alone (t-test). c. Carboxypeptidase protection assays. Anti-Mfn2 recognizes HR2 (hMfn2 amino acids 661-758). Arrows show Mfn2; gel source data are in Extended Data Figure. 1. d. Mfn2 live cell FRET studies. Representative images are on the left; quantitative data (mean±SEM, n=10) are to the right. Arrow indicates time of TAT-peptide addition.

Correcting mitochondrial fusion defects

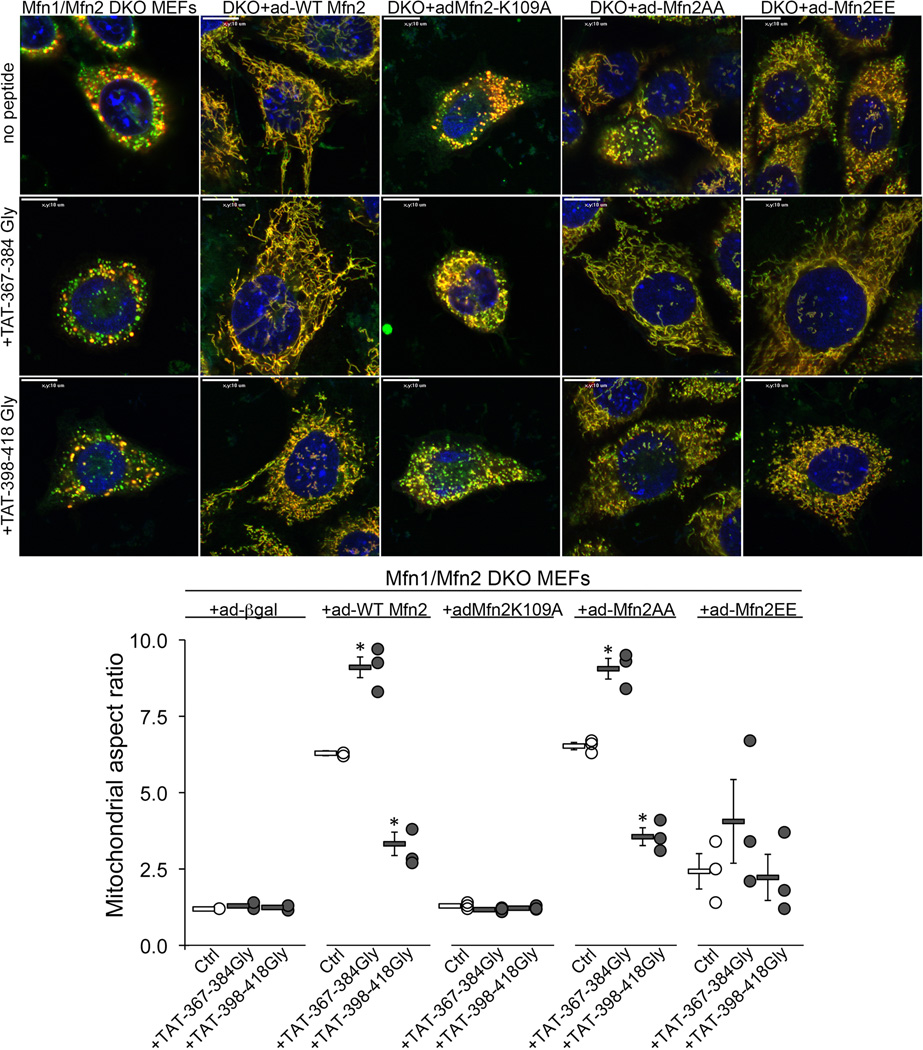

Pathological mitochondrial fragmentation in CMT2A is caused by nonsense or damaging non-synonymous Mfn2 mutations7. Compound nonsense Mfn2 mutations in autosomal recessive CMT2A are simulated by Mfn2 gene ablation. TAT-367-384Gly treatment for 24 hours normalized mitochondrial aspect ratio of Mfn2 KO MEFs (Extended Data Figure. 5). However, TAT-367-384Gly did not correct mitochondrial fragmentation in Mfn1/Mfn2 null MEFs after adenoviral introduction of mouse Mfn2 K109A, a GTPase defective mutant15 (although mitochondrial clumping suggested enhanced mitochondria-mitochondria tethering in the absence of organelle fusion) (Extended Data Figure. 6). An Mfn2 AA mutant with normal fusion activity but defective Parkin binding (T111 and S442 alanine mutants12,13) responded like WT Mfn2.

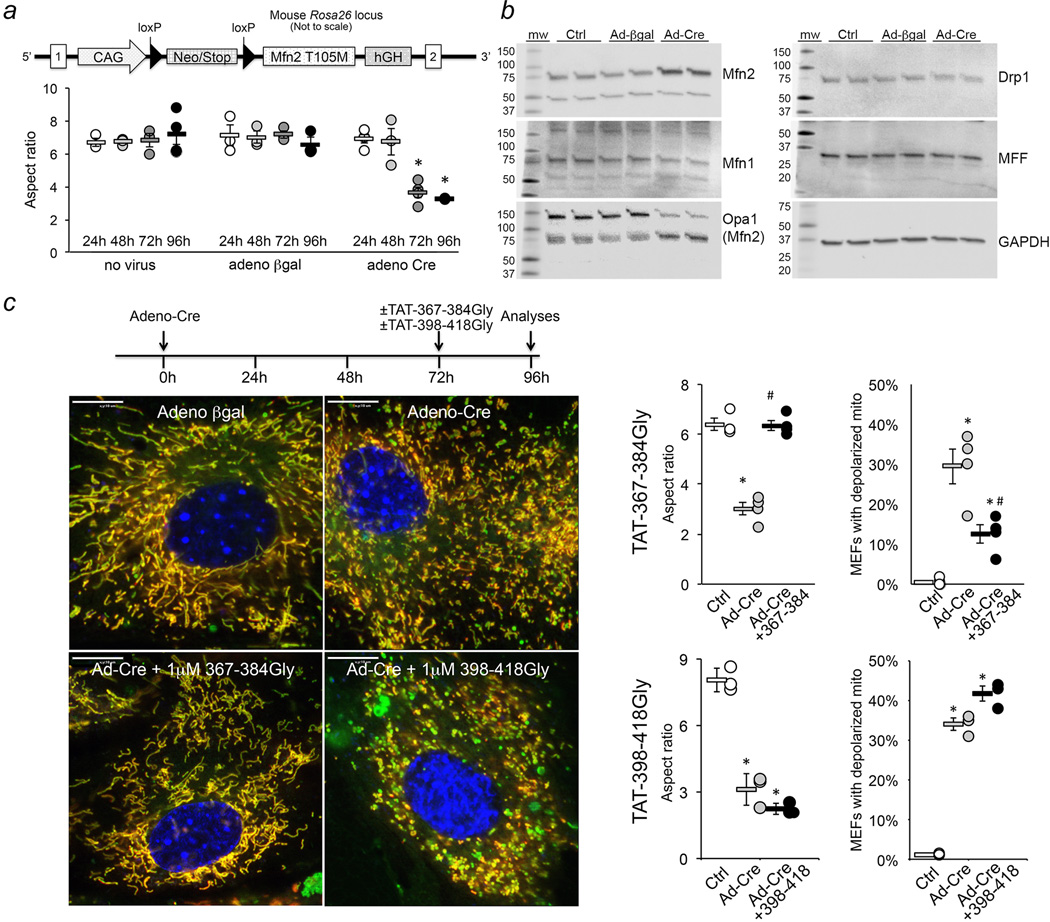

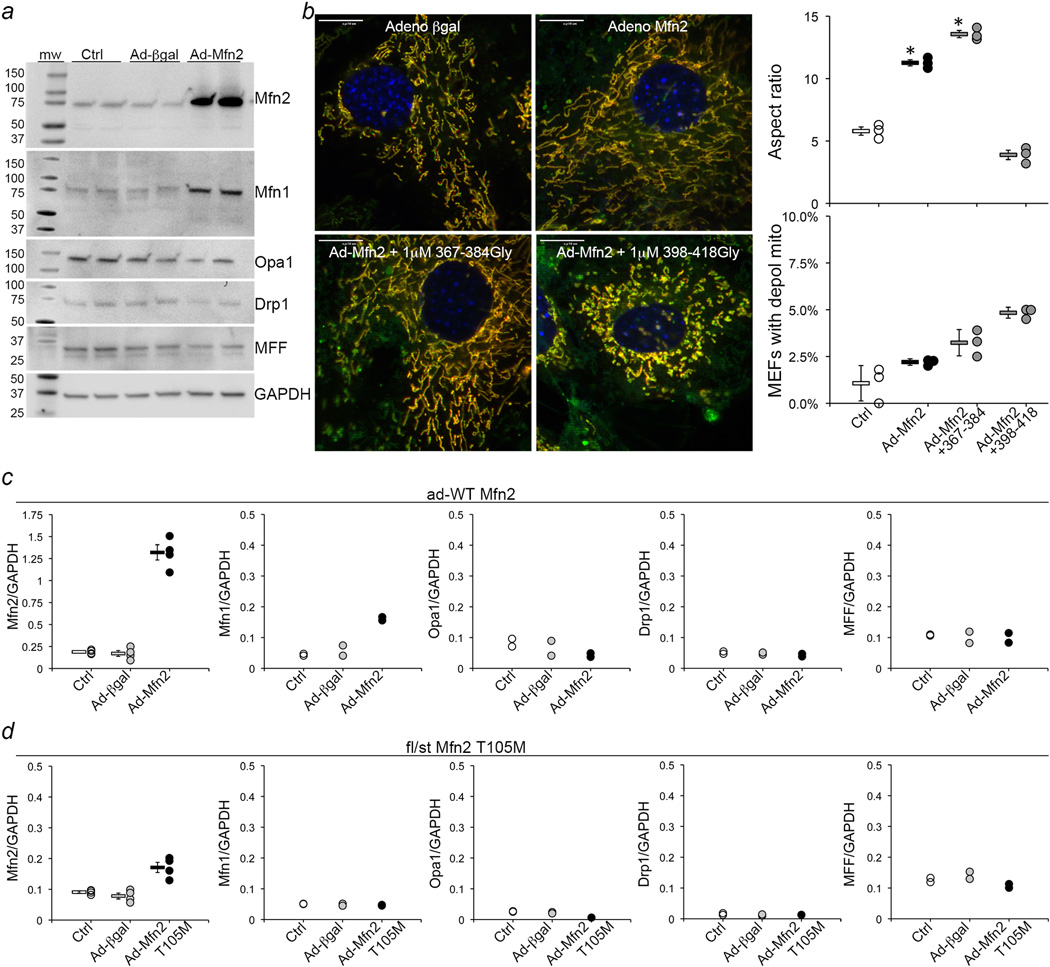

These findings hinted at therapeutic potential of compelling endogenous normal mitofusins into their active unfolded conformation in order to overcome dominant inhibition by GTPase-defective Mfn2 mutants in diseases like CMT2A. We tested this notion in MEFs expressing the CMT2A-causal mutant hMfn2 T105M16,17 as a conditional flox/stop (fl/st) transgene (Figures 4a and 4b). Mitochondria of Mfn2 T105M fl/st MEFs fragmented and depolarized after adenoviral-Cre application (Figures 4a and 4c), but 1 µM TAT-367-384Gly rapidly reversed mitochondrial abnormalities (Figure 4c). (Further suppressing mitochondrial fusion with TAT-398-418Gly aggravated mitochondrial dysmorphology and exacerbated mitochondrial depolarization induced by Mfn2 T105M; Figure 4c). Parallel adenoviral expression of WT Mfn2 at more than twice the levels of Mfn2 T105M (5-fold vs 2-fold) provoked neither mitochondrial nor cellular toxicity (Extended Data Figure. 7).

Figure 4. TAT-367-384Gly normalizes mitochondrial dysmorphology induced by the CMT2A mutant Mfn2 T105M.

a. (top) Schematic representation of the conditional T105M transgene construct. (bottom) Time course of mitochondrial fragmentation after adeno-Cre mediated induction of Mfn2 T105M. Group data are mean±SEM, N=3; *=P<0.05 vs 24h same treatment group (ANOVA). b. Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial dynamics factors in Mfn2 T105M MEFs treated as indicated above; gel source data are in Extended Data Figure. 1 and quantitation is in Extended Data Figure 8d. c. Confocal micrographs (representative of >15/group) showing mitochondrial fragmentation evoked by Mfn2 T105M, its normalization 24h after application of 1 µM TAT-367-384Gly, and its exaggeration 24h after 1 µM TAT-367-384Gly. Experimental design is depicted above. Scale bars are 10 microns. On the right are group data; N=3 or 4. Group data are mean±SEM; *=P<0.05 vs Ctrl, #=P<0.05 vs Ad-Cre (ANOVA).

Repairing neuronal CMT2A pathology

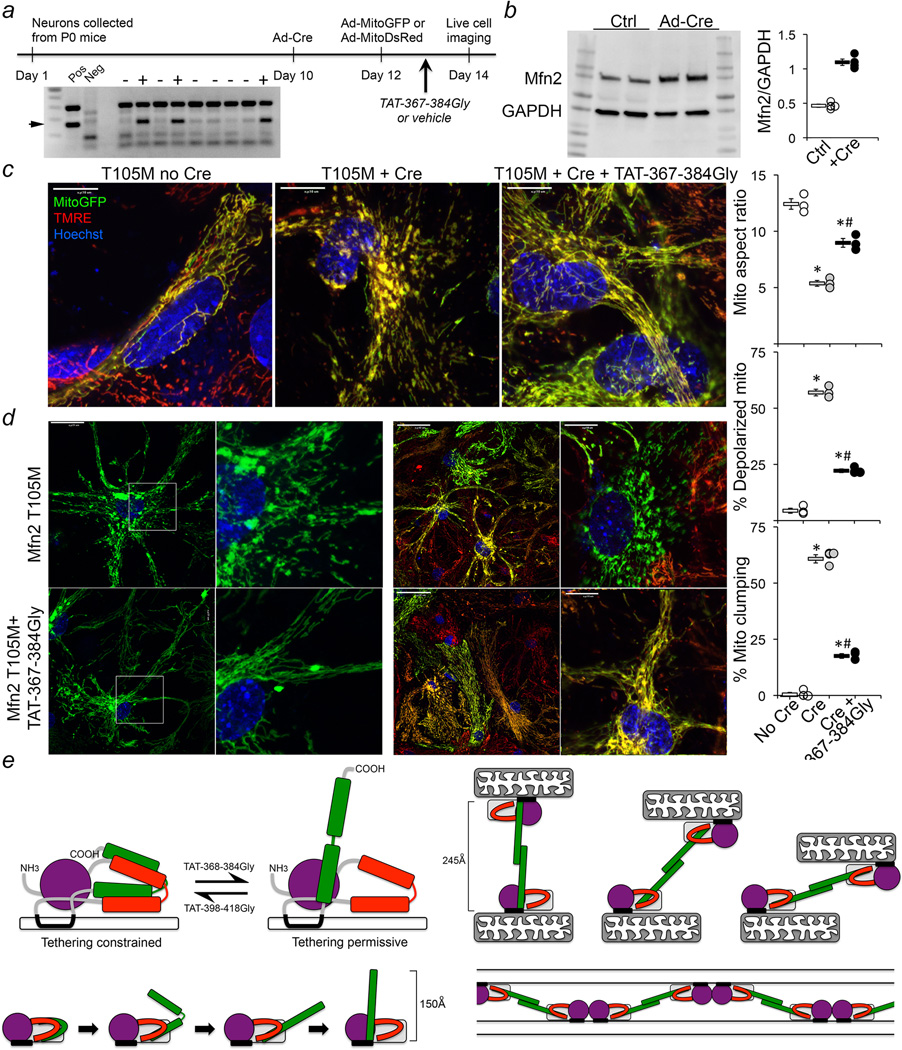

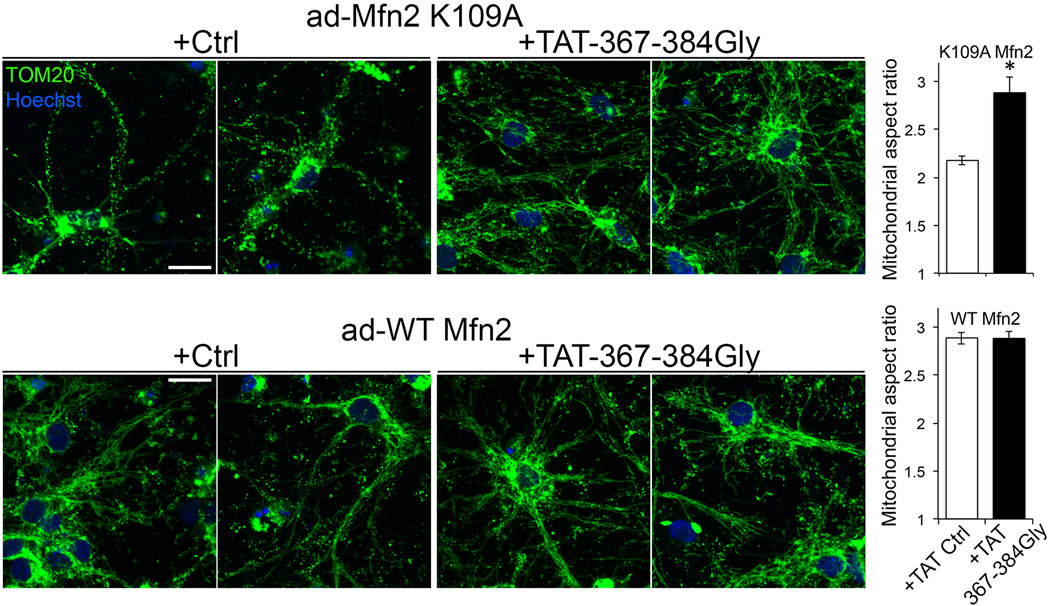

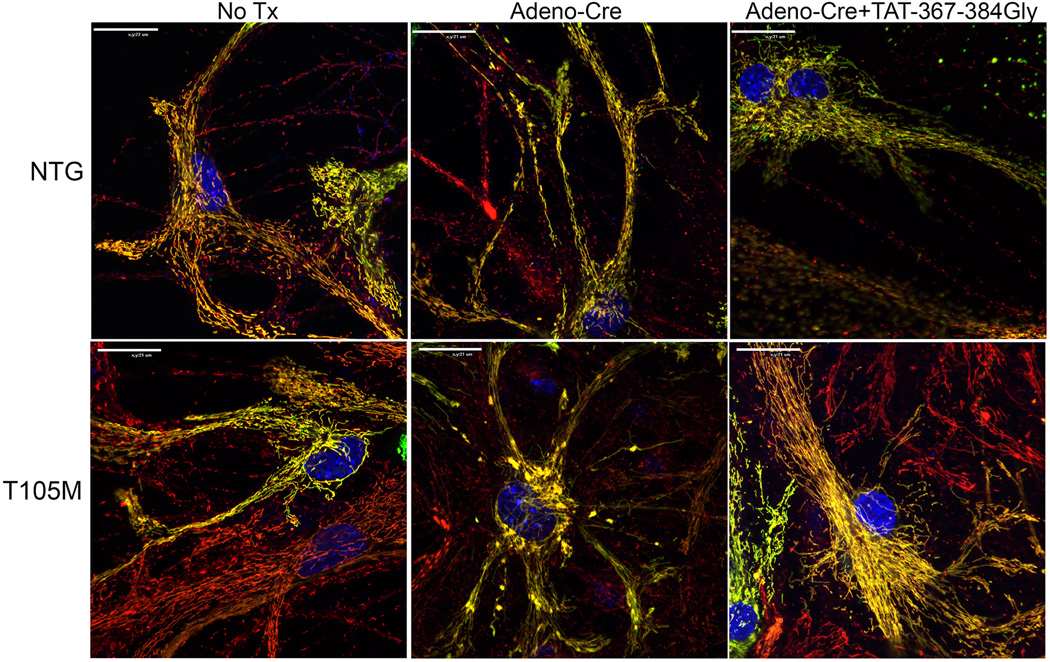

The relevant cell type in CMT2A is neurons. TAT-367-384Gly corrected mitochondrial pathology in cultured rat motor neurons transfected with the engineered GTPase-defective mutant Mfn2 K109A (Extended Data Figure. 8). We further tested fusion promotion by conformational manipulation of Mfns in a model of a naturally-occurring human CMT2A mutation: cultured neurons from mouse pups carrying the conditional Mfn2 T105M fl/st expression allele (Figure 5a). Live cell analyses demonstrated that adeno-Cre induction of Mfn2 T105M (Figure 5b) evoked widespread neuronal mitochondrial dysmorphology with fragmentation and partial depolarization (Figures 5c, 5d; Extended Data Figure. 9). Mitochondrial clumping was prevalent after Mfn2 T105M induction, consistent with interrupting GTP-dependent mitochondrial fusion while not interfering with GTPase-independent mitochondrial tethering (Figure 5d). TAT-367-384Gly (1 µM) application for 24 hours largely reversed these abnormalities (Figures 5c and 5d; Extended Data Figure. 9).

Figure 5. TAT-367-384Gly corrects mitochondrial pathology in CMT2A Mfn2 T105M mouse neurons.

a. Experimental design. Inset shows PCR genotyping of a Mfn2 T105M fl/st transgene (arrow) mouse litter whose pups were used for neuron harvesting and culture. b. Immunoblot of Mfn2 expression in T105M fl/st cortical neurons 72h after adeno-Cre or adeno-β-gal (Ctrl) (quantitative data to the right are n=4); gel source data are in Extended Data Figure. 1. c. Merged live confocal images of cultured neurons without (no Cre) and with (+ Cre) Mfn2 T105M induction, and in Mfn2 T105M-induced neurons 24h after addition of 1 µM TAT-367-384Gly. Scale bars are 10 microns. d. Mfn2 T105M expressing neurons without (top) and with (bottom) 24h treatment with 1 µM TAT-367-384Gly. Scale bars are 40 microns in low power images and 10 microns in high power images. Quantitative data are to the right; each point is result from one of 3 independently-established Mfn2 T105M neuronal cultures, each with 3 biological replicates of ~20 neurons. Group data are mean±SEM; * = P<0.01 vs no Cre; # = P<0.01 vs T105M+Cre. e. (left) Schematic depiction of the folded/HR2-constrained (left) and unfolded/HR2-extended (right) mitofusin conformations; HR2 unfolding is below. (right) HR2 flexing at Gly 623/642 after trans-association of HR2 domains; molecular patch formed between mitochondria by coincident GTP-dependent/GTPase domain-mediated cis Mfn2 dimerization is below.

Discussion

Here, by combining computational modeling based on the crystal structure of bacterial DLP with functional interrogation of intra-molecular interactions using engineered competing peptides we provide evidence for two functionally distinct conformational states of mammalian mitofusins. Opposing effects of the engineered minipeptides on mitochondrial fusion were linked to their reciprocal modulation of mitofusin HR1 folding/unfolding.

The canonical representation of Mfn1 and Mfn2 as described by Chan and colleagues8 is a molecule anchored to the outer mitochondrial membrane by a transmembrane domain, having both amino and carboxyl structures extending perpendicularly into the cytosol. This resembles an unfolded mitofusin conformation optimal for mitochondrial tethering, and therefore permissive for fusion. Our model suggests, however, that the core globular Mfn molecule is adherent to the mitochondrial membrane. Moreover, in the resting or tethering non-permissive state HR2 is restrained by antiparallel intra-molecular binding to HR1; destabilization of HR1-HR2 binding unfolds and extends HR2 into the cytosol, i.e. into a tethering-permissive state.

Conformational plasticity has important implications for mitochondrial gap distance maintained by Mfn-Mfn tethering, variously reported as 78±37A18 or 159±30A8. Based on a calculated HR2 arm length of 150A beginning from the putative Gly “shoulder” at the carboxyl terminus of the transmembrane domain (hMfn1 Gly 623; hMfn2 Gly 642), and accounting for the 60 amino acid overlap of the HR2-HR2 homodimer, the maximal tethered mitochondrial gap distance according to our model would be 245A. However, flexing of each Mfn HR2 at its shoulder would retract tethered mitochondria into close juxtaposition (Fig. 5e), narrowing the gap. The crystal structure of bacterial DLP indicates that GTP binding promotes its dimerization at GTP domains9. The same GTP-dependent event for Mfn2 would, with concomitant trans-dimerization of HR2 domains, create a multimeric molecular patch between two adjoining mitochondria, greatly facilitating GTP-dependent outer membrane fusion (Fig. 5e). Thus, Mfn structural malleability may be important not only to initiate tethering, but to facilitate the progression from organelle tethering, to apposition, to union.

In designing our conformation-altering minipeptides we contemplated the difficulty of destabilizing a constrained Mfn structure using peptides identical to the parent HR1 domains with which they were intended to compete. Accordingly, we substituted rotational Gly residues for Leu residues facing away from the putative HR1-HR2 (367-384Gly) and HR2-HR2 (398-418Gly) interaction sites. The importance of minipeptide flexibility at these sites was confirmed by their functional inactivation by rigid Pro substituted at the same positions.

Our fusogenic cell-permeant peptide, TAT-367-384Gly, reversed mitochondrial dysmorphology and depolarization in otherwise normal MEFs and cultured neurons expressing either the artificial GTPase-deficient K109A Mfn2 mutant or the naturally occurring human CMT2A GTPase mutant, Mfn2 T105M. Because TAT-367-384Gly did not correct mitochondrial pathology induced by Mfn2 K109A in mitofusin null cells, we conclude that rescue of the in vitro CMT2A models accrues from enhanced mitochondrial tethering/fusion mediated by endogenous normal Mfn1 and Mfn2. Most CMT2A mutations, including Mfn2 T105M, are autosomal dominant; patients have one mutant Mfn2 allele, one normal Mfn2 allele, and two normal Mfn1 alleles7. Thus, rather than relying on genetic engineering to correct or silence Mfn2 gene mutations, an approach of pharmacologically unfolding endogenous normal mitofusins to promote mitochondrial tethering and enhance fusion could prove beneficial in CMT2A and pathophysiologically-related diseases.

Methods

Cell lines

Wild-type MEFs were prepared from E10.5 C57/b6 mouse embryos. SV-40 T antigen-immortalized Mfn1 null (CRL-2992), Mfn2 null (CRL-2993) and Mfn1/Mfn2 double null MEFs (CRL-2994) originally developed by David Chan2 were purchased from ATCC. MEFs conditionally expressing the human Mfn2 T105M mutation were prepared from E10.5 embryos of C57BL/6-Gt(ROSA)26Sor[tm1(CAG-MFN2*T105M)Dple]/J mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Stock No: 025322). All cell lines were tested for mycoplasma and found to be mycoplasma free. MEFs were maintained in DMEM containing 4.5g/L glucose (or galactose when specified) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1× nonessential amino acids, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100U/ml penicillin and 100ug/ml streptomycin.

Cultured mouse neurons

Hippocampal and cortical neurons were prepared from individual P0-P1 mouse pups using a modification of methods described for rat neuronal culture21. Mouse pups were genotyped after the fact to determine presence or absence of the MFN2*T105M transgene; neurons derived from mice lacking the transgene were designated as normal controls. After 10 days of culture neurons were infected with Adeno-Cre or Adeno-βgal control (50 MOI). 72 hours later 1 µM TAT-367-384Gly or vehicle was added. Live neurons were imaged as described below.

Cultured rat motor neurons

Motor neurons were isolated from E17 Sprague-Dawley rats and cultured as described22. After 10 days in culture neurons were infected twice, 8 hours apart, with 50 MOI of adenoviral WT-Mfn2 or K109A Mfn2 and treated with 1 µM TAT-367-384Gly or control TAT peptide for 24 hours. Mitochondria of formalin-fixed neurons were labeled with anti-TOM20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); neurons were stained with Hoechst 33342. Laser confocal imaging using a 63× oil objective was used to identify isolated mitochondria for determination of aspect ratio.

Adenoviral stocks

Empty adenovirus (Ad-CMV-Null; #1300) and adenoviruses expressing β-Galactosidase (Ad-CMV-b-Gal; #1080) or Cre recombinase (Ad-CMV-iCre; #1045) were from Vector Biolabs. Adenoviral expression vectors for hMfn2 HR1 and the minipeptides and their Gly or Pro mutants were generated and amplified using standard methods. Adenoviral vectors were added to MEFs at 50% confluence at an MOI of 100. Adeno-PA-GFP (mitoGFP) and adeno-mitoDsRed2 (both from SignaGen Laboratories) were added to cultured mouse neurons at an MOI of 10 or 50.

Antibodies and immunoblotting

Anti-Mfn1 (sc-50330) and -Opa1 (sc393296) were from Santa Cruz. Anti-Mfn2 (ab56889) -Drp1 (ab56788), and -GAPDH (ab8245) were from Abcam. Anti-MFF (17090-1-ap) was from Proteintech. Cell protein lysates were size-separated on 10% SDS-PAGE gels, transferred onto nylon membranes, incubated with primary antibody and detected with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody (Cell Signaling, 7076S, 1:4000) or goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Thermo Scientific, 31460, 1:4000) using ECL enhanced chemiluminescence substrate (PerkinElmer, NEL105001EA) on a Li-COR Odyssey system for digital acquisition. Gel source data are in Supplementary Figure 1

Carboxypeptidase protection assay of Mfn2

Mitochondrial membranes were prepared6 from mouse hearts overexpressing human Mfn213 and digested with 200 ng/ml each carboxypeptidases A and B (Sigma-Aldrich) for increasing times at room temperature, followed by immunoblotting using an antibody (Abcam ab56889) specific to hMfn2 HR2.

Live cell imaging

MEFs or neurons were grown on chamber slides and infected with recombinant adenoviri for 48–72 hours unless otherwise indicated. MEFs were stained with MitoTracker Green (200 nM, Invitrogen M7514) and Hoechst (10mg/ml, Invitrogen H3570), with or without tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE; 200 nM, Invitrogen T-669). Neuronal mitochondria were labeled with adenoviral-expressed mitoGFP plus TMRE, or with adeno-mitoDsRed for time-lapse studies. Cover slips were loaded onto a chamber (Warner instrument, RC-40LP) in modified Krebs-Henseleit buffer (138 mM NaCl, 3.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 15 mM Glucose, 20 mM HEPES and 1 mM CaCl2) at room temperature and visualized on a Nikon Ti Confocal microscope equipped with a 60× 1.3NA oil immersion objective. For mitophagy studies MEFs were stained with MitoTracker Green and infected with adeno-mcherry Parkin or stained with LysoTracker Deep Red (50 nM, Invitrogen L-7528); carbonylcyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP, 10 µM for 1 hour) was applied as a positive control. Mitochondrial fusion was measured at 2 and 6 hours after PEG-mediated cell fusion of MEFs treated 48 hours previously with adeno-mitoGFP or adeno-mitoDsRed14. Laser confocal fluorescence was excited with 561 nm (MitoTracker Green, GFP, FITC), 637 nm (TMRE, LysoTracker Red, mcherry-Parkin, MitoTracker Orange) or 408 nm (Hoechst) laser diodes.

Image analysis

Mitochondrial aspect ratio was calculated using automated edge detection and Image J software as described6. Mitochondrial depolarization was calculated as % of green mitochondria visualized on MitoTracker Green and TMRE merged images, expressed as green/(green + yellow mitochondria) × 100. Parkin aggregation was calculated as % of cells with mitochondrial clumping of mcherry-Parkin6. Lysosomal engulfment of mitochondria was identified by co-localization of LysoTracker Red and MitoTracker Green6.

TAT-minipeptide design, synthesis and use

We designed three polypeptides derived from Mfn2, two from the HR1 region flanking its REQQ bend and one from the adjacent C-terminal area between HR1 and the transmembrane domain. Since these peptides are derived from α helical domains we attempted to conserve their secondary structure by maintaining a length of ~20 amino acids, which was predicted to create a stable α helix of about 5 turns. We considered that the native ~20 amino acid polypeptides might not effectively compete with the endogenous HR1-HR2 interactions as they each represent only a portion of the overall HR1 interacting domain. Therefore, we generated two analogs for each of the three polypeptides, substituting either Gly or Pro for a mid-peptide Leu. We predicted that substituting Gly for the central Leu residues would increase rotational flexibility of the peptide and enhance its ability to compete for and interfere with endogenous inter-domain interactions in intact Mfn2. Conversely, we reasoned that peptides in which Pro substituted for the central Leu residue would be less active as the α helix would be kinked, thus limiting competition for endogenous interactions. The nine polypeptides were expressed using adenovirus as mini-genes for screening and initial characterization. The two biologically active polypeptides, Mfn2 367-384Gly and 398-418Gly, were chemically synthesized and introduced into cells using TAT47–57 conjugation, which enabled transmembrane delivery20. Except for dose-response studies, 1 mM stock concentrations of TAT-minipeptides in sterile water were applied to cultured MEFs at a dilution factor of 1:1000 or 1:200 to achieve final concentrations of 1 or 5 µM.

Parent peptide sequences (central Leu that was mutationally substituted is bold) are:

Mfn2 367-384: DIAEAVRLIMDSLHMAAR

Mfn2 398-418: QDRLKFIDKQLELLAQDYKLR

Mfn2 428-448: RQVSTAMAEEIRRLSVLVDDY

GTPase assay

Minipeptide effects on Mfn2 GTPase activity were evaluated by incubating recombinant Mfn2 (100 ng, OriGene, Rockville, MD) with 1 µM control TAT peptide, TAT-367-384Gly, or TAT-398-418Gly for 15 minutes prior to addition of 0.5 mM GTP for 1 hour at 37 °C. GTPase activity relative to no-peptide control was measured using a colorimetric GTPase assay kit (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Minipeptide-Mfn2 binding assay

Mfn2 was bound to carboxylic acid sites of AGILE (Nanomedical Diagnostics, San Digeo CA) graphene chips23 as previously described24. Minipeptides were applied at varying concentrations (500 nM – 1 mM) and the change in sensor chip charge recorded for 15 min. Responses of 25 sensors on a single assay chip were averaged. A Hill equation fit was used to derive Kd. All samples were identical prior to allocation of treatments and analyses were performed by an observer blinded to the experimental conditions.

Mfn2 FRET assay

mCerulean1 and mVenus were cloned onto the 5’ and 3’ ends of hMfn2 cDNA in pcDNA3.1 and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Lipofectamine-transfected biosensor-expressing HEK 293T cells were imaged on an Olympus IX81 ZDC inverted microscope under 40× magnification. mCerulean was excited at 436 nm with emission at 480 nm. mVenus was excited at 500 nm with emission at 535 nm. FRET was imaged with excitation at 436 nm and emission at 535 nm. Studies were performed after adding GTPγS (1 mM, Sigma-Aldrich) to suppress Mfn2 GTPase activity. Live cell FRET data were acquired every 60 seconds for 15 minutes before and 90 minutes after addition of TAT-minipeptides (5 µM).

Computational modeling of Mfn2 structure

The I-TASSER (Iterative Threading ASSEmbly Refinement) hierarchical approach to protein structure was used to derive a structural model of Mfn219. Structural templates are identified from the PDB database through sequence similarity searches (threading); The top ten solutions were based on the bacterial dynamin-like protein structures in the PDB (ID: 2J69). The confidence of each model is quantitatively measured by C-score calculated based on the significance of threading template alignments and the convergence parameters of the structure assembly simulations. C-score is typically in the range of [−5, 2], where a C-score of a higher value signifies a model with a higher confidence and vice-versa. C-score in the top solution was −1.14. Another measure of the quality of a predicted structure is its estimated TM score. TM-score is a scale for measuring structural similarity and is estimated based on the C-score and protein length following the correlation observed between these qualities. A TM-score > 0.5 indicates a model of correct topology and a TM-score < 0.17 means a random similarity. The estimated TM-score of the top solution is 0.57±0.15. Energy minimization and analysis of the structure was performed with MAESTRO tools (Maestro, version 10.5, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2016). PYMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. Version 1.7; Schrödinger, LLC: New York, 2014) was used for preparing images and videos.

Statistical analyses

Sample size for mitochondrial studies was established a priori based on published experiments having similar endpoints6; experimental variance was similar between study groups and cell lines. Data are reported as mean±SEM. Statistical comparisons (two-sided) used one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test for multiple groups or Student’s t-test for paired comparisons. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

Extended Data

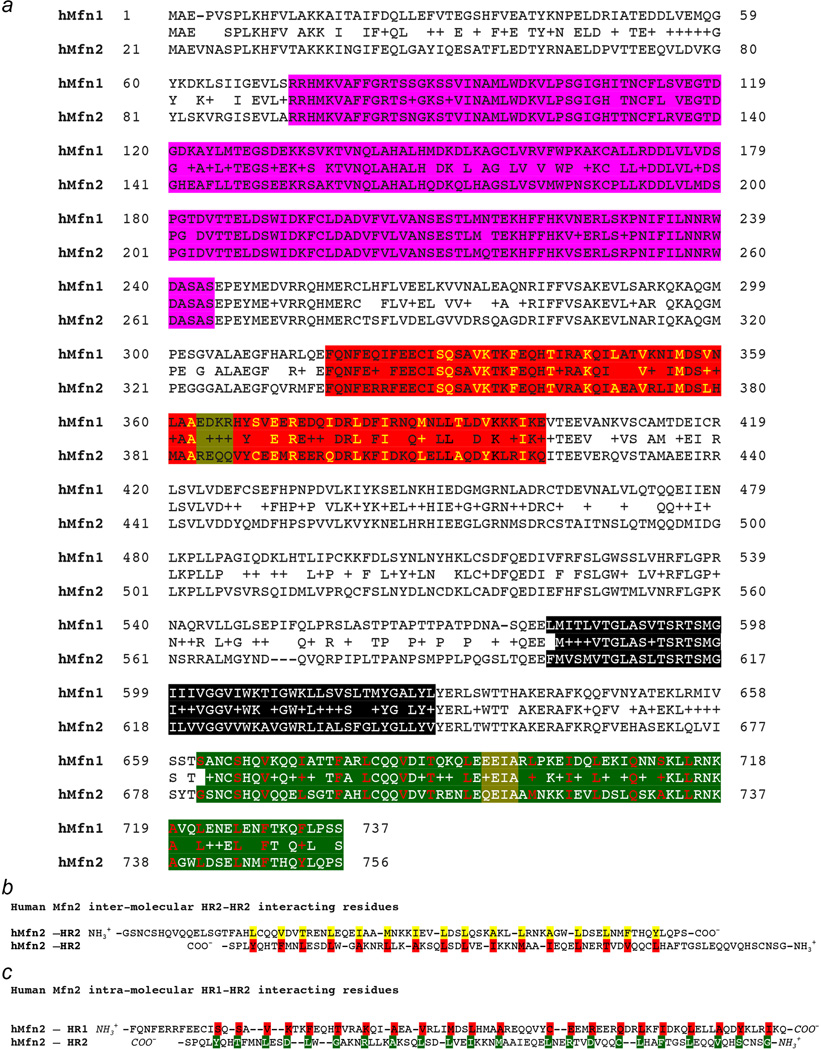

Extended Data Figure 1. Interacting domains in human mitofusins.

a. Amino acid alignment of human Mfn1 and Mfn2. Conservative amino acid substitutions are indicated by +. Mfn domains are color-coded as in Fig 1a: purple is GTPase, red is HR1, black is TM, green is HR2. Yellow amino acids in HR1 and red amino acids in HR2 are residues central to inter- or intra-molecular binding. Areas where local unfolding of HR1 and HR2 α-helices occurs are highlighted yellow-green. b. Antiparallel inter-molecular Mfn2 HR2-HR2 binding as predicted from reference 8. c. Intra-molecular Mfn2 HR1-HR2 binding as depicted in Figure 1c and Supplemental video 2.

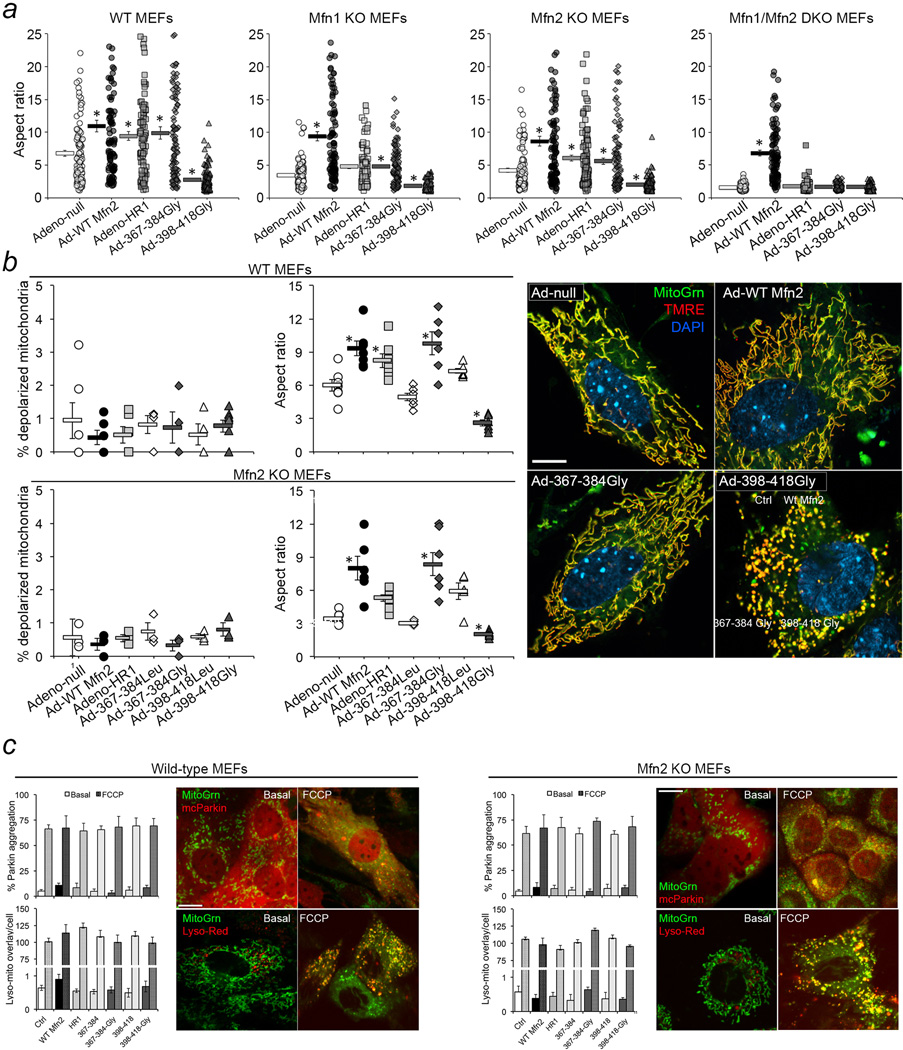

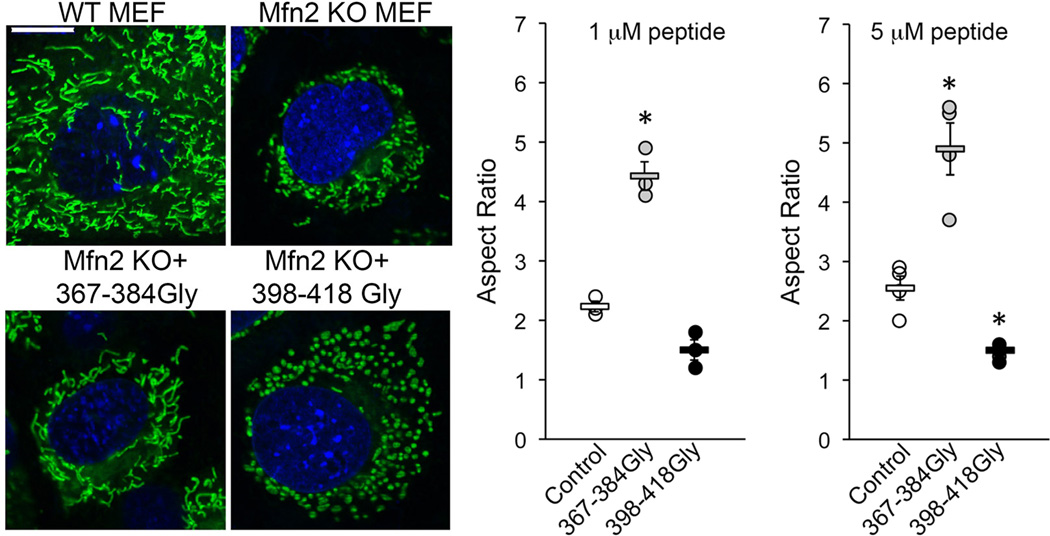

Extended Data Figure 2. Adenovirally-expressed Gly-substituted mini-peptides derived from Mfn2 HR1 specifically regulate Mfn-mediated mitochondrial fusion.

a. Changes in mitochondrial aspect ratio provoked by adeno-367-384Gly and adeno-398-418Gly in MEFs having different Mfn expression profiles, compared to adeno-WT Mfn2 and adeno-(Mfn2) HR1. Each point is the aspect ratio of an individual mitochondrion; Group data are meanαSEM; *=P<0.05 vs adeno-null (ANOVA). Exact numbers of mitochondria measured from 4 or 5 separate experiments per condition are shown on the figure. b. Mitochondrial polarization status and aspect ratio in WT and Mfn2 KO MEFs expressing WT Mfn2 or fragments thereof. Each point is the mean of ~20 mitochondria from ~5 cells in the number of independent experiments indicated on the graph. Group data are meanαSEM; *=P<0.05 vs ad-null Ctrl (ANOVA). Representative (of 15–40 images/group) merged confocal images of WT MEFs infected with ad-Mfn2 or the two biologically active Ad-peptides are to the right; scale bar is 10 microns. c. MitoTracker Green and m-cherry Parkin (top) or Lyso-Red (bottom) co-stained WT or Mfn2 KO MEFs before (left) or 1 hour after (right) treatment with 50 nM FCCP. Group data are meanαSEM; there were no differences between groups (ANOVA; n=3 independent experiments per condition). Scale bars are 10 µm.

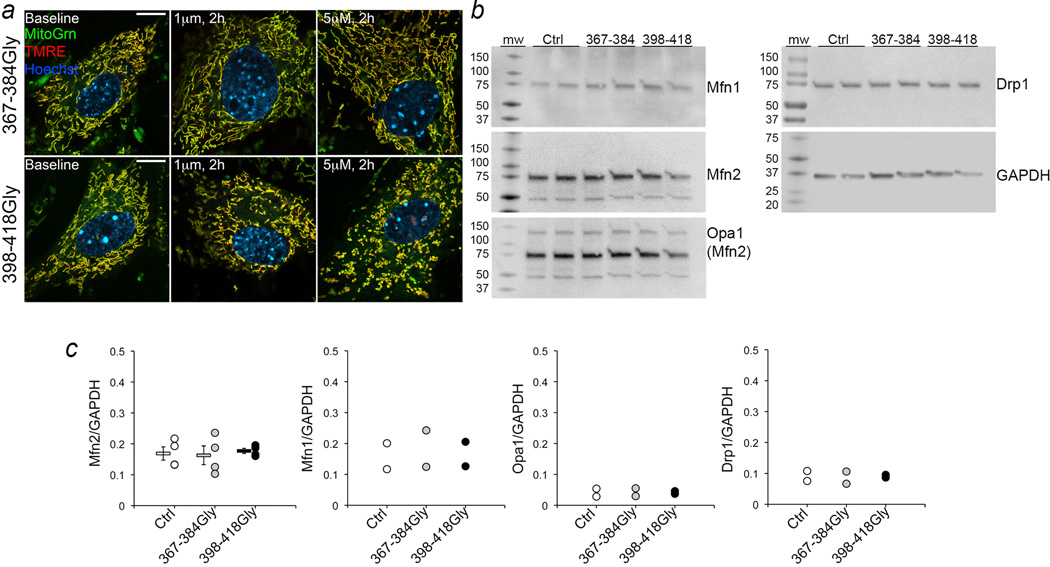

Extended Data Figure 3. Effects of TAT-conjugated mini-peptides on MEFs.

a. Merged confocal images (representative of 30) of mitochondria in MEFs 2 hours after application of TAT-367-384Gly (top) or TAT-398-418Gly (bottom). Complete dose-response relationship is in Figure 2d. b. Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial dynamics proteins 4 hours after application of TAT-367-384 Gly or TAT-398-418 Gly. Opa1 is the inner mitochondrial membrane fusion protein Optic atrophy 1; Drp1 is the fission protein Dynamin related protein 1. Opa1 immunoblot was co-probed for Mfn2. c. Immunoblot quantitation. MeanαSEM; N=4 for Mfn2;, n=2 for all other proteins. Un-cropped original blots are in supplementary information Figure 1.

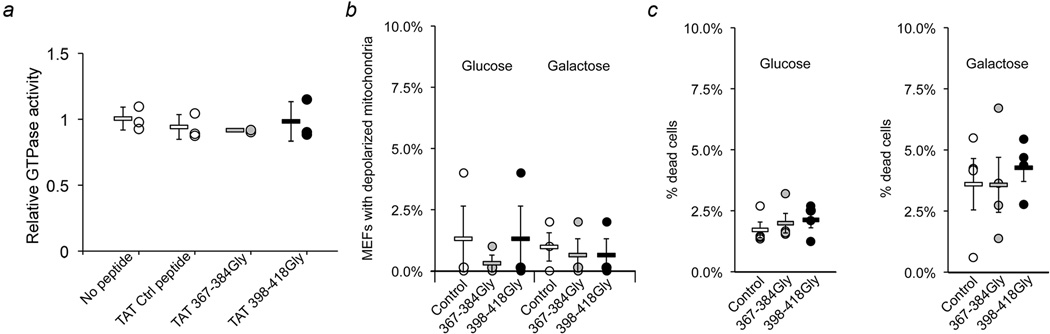

Extended Data Figure 4. Mfn2 HR1-derived TAT-mini-peptides do not suppress GTPase activity, impair mitochondrial polarization, or increase cell death.

a. Relative GTPase activity of recombinant Mfn2 is shown with respect to a no-Peptide control. Background signal from no GTP blank was subtracted from each value prior to normalization. Mean αSD of 3 independent experiments. b and c. Mitochondrial depolarization was assessed as loss of TMRE staining (b) and cell death was assessed as ethidium bromide uptake (c) in WT MEFs cultured in 4500 mg/L glucose (left) or galactose (right) treated with or without 1 µM TAT-mini-peptide for 24h. N=3 or 4 independent experiments per condition. All group data in panels a-c are mean α SEM. There were no significant differences between TAT-mini-peptide treatment groups (ANOVA).

Extended Data Figure 5. TAT-367-384Gly rescues mitochondrial dysmorphology in a cell model of autosomal recessive CMT2A. (left).

Representative (of 15–20/group) confocal micrographs of MitoTracker green/Hoechst stained Mfn2 KO MEFs at baseline or 24h after application of mini-peptide; a representative normal MEF is shown for comparison. Mean normal MEF mitochondrial aspect ratio is 6.2. Group data are meanαSEM; * is P<0.05 vs control (ANOVA), n=3 or 4 per group. Scale bar is 10 microns.

Extended Data Figure 6. Minipeptide effects on dysfunctional Mfn2 mutants.

WT Mfn2 or the indicated mutants were expressed for 48 h using adenoviri (ad) in Mfn null MEFs (Mfn1/Mfn2 DKO). TAT minipeptides or vehicle (sterile water) were added and mitochondrial morphometry assessed 24 hours later. Images (representative of 15/group) are merged MitoTracker Green (green) and TMRE (red). Scale bars are 10 µm. Quantitative data for aspect ratio is shown below (n=3/condition). Group data are meanαSEM; *=P<0.05 vs same-group Ctrl (ANOVA).

Extended Data Figure 7. WT Mfn2 expression to parallel Mfn2 T105M expression studies.

a. Immunoblot analysis of mitochondrial dynamics proteins in cultured MEFs transduced with ad-βgal (viral control) or Ad-Mfn2 (adenoviral wild-type human Mfn2). Mfn2 expression increased 5-fold over uninfected Ctrl; apparent increased Mfn1 signal is cross immunoreactivity with Mfn2 as shown by slightly faster migration. b. Merged confocal images (MitoTracker Green and TMRE; representative of 15/group) of MEFs expressing WT Mfn2 and treated with TAT-minipeptides as shown. Quantitative data (n=3 independent experiments) are on the right. Group data are meanαSEM; * = P<0.05 vs Ctrl by one-way ANOVA. Scale bars are 10 µm. c. Immunoblot quantifications for panel a. d. Immunoblot quantifications for Figure 4b, for comparison. N=4 for Mfn2; n=2 for all other proteins. Y axis scales are identical except Mfn2 in (panel c), which is expanded to accommodate high (5× normal) ad-WT Mfn2 expression level.

Extended Data Figure 8. TAT-367-384Gly corrects mitochondrial fragmentation provoked by Mfn2 K109A in cultured rat motor neurons.

Representative (of > 20/group) anti-TOM20/Hoechst images of formalin-fixed cultured neurons infected with adeno-Mfn2K109A (top) or adeno-WT Mfn2 (bottom) and treated for 24 h with 1 µM TAT control (Ctrl) or TAT-367-384Gly minipeptide. Scale bars are 10 microns. Experimental n per treatment group is shown on the graph. Data are meanαSEM;*=P<0.05 vs Ctrl (Student’s t-test).

Extended Data Figure 9. TAT-367-384Gly reverses mitochondrial pathology in cultured Mfn2 K109A mouse neurons.

Live-cell confocal imaging of MitoGFP (green)/ TMRE (red)/ Hoechst (blue nuclei) stained mouse hippocampal neurons (representative of >30 images/group). Normal control neurons from nontransgenic (NTG) mouse pups are on top; Mfn2 T105M fl/st transgenic mouse neurons are on bottom. Adeno-MitoGFP was added at low titers to enhance visualization of individual neurons. Note mitochondrial fragmentation and clumping after adeno-Cre induced induction of Mfn2 T105M, and reversal after 24h of TAT-367-384Gly treatment. Scale bars are 20 microns.

Supplementary Material

Purple is GTPase domain, red is HR1, black is transmembrane domain, green is HR2.

Purple is GTPase domain, red is HR1, black is transmembrane domain, green is HR2.

Purple is GTPase domain, red is HR1, black is transmembrane domain, green is HR2.

Purple is GTPase domain, red is HR1, black is transmembrane domain, green is HR2.

White frames show cropping

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institutes of Health HL59888, HL128441 (GWD), HL128071 (RNK and GWD), CA178394 (EG), MH078823 (SM), CA205262 (LH), HL52141 (DM-R) and American Cancer Society PF-15-135-01-CSM (SKD). AF is supported by a fellowship from Societa' Italiana ipertensione arteriosa SIIA. GWD is the Philip and Sima K. Needleman endowed Professor.

GWD and DM-R have applied for a patent for using fusion-modifying peptides in diseases with abnormal mitochondrial dynamics. DM-R is a founder of MitoConix, but none of this work was supported by or performed in collaboration with the company.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author contributions

GWD, DM-R, RNK, LH, and SM conceived of or designed the research. GWD wrote the manuscript. AF, JAF, GG performed functional studies of minipeptides in MEFs. AF, AB, OK performed functional studies of minipeptides in neurons. AF and GWD performed minipeptide mitochondrial colocalization. AF performed immunoblotting. NQ performed peptide-Mfn2 binding studies. OK performed Mfn2 GTPase assays. SKD, LH, YC performed Mfn2 FRET. EG and NB performed computational modeling and domain interaction analyses. EG, NB, GWD, RK generated structural images. Reprints and permissions information are available at www.nature.com/reprints.

The other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Chan DC. Fusion and fission: interlinked processes critical for mitochondrial health. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:265–287. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen H, et al. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasahara A, Cipolat S, Chen Y, Dorn GW, 2nd, Scorrano L. Mitochondrial fusion directs cardiomyocyte differentiation via calcineurin and Notch signaling. Science. 2013;342:734–737. doi: 10.1126/science.1241359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell. 2007;130:548–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, et al. Mitochondrial fusion is required for mtDNA stability in skeletal muscle and tolerance of mtDNA mutations. Cell. 2010;141:280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song M, Mihara K, Chen Y, Scorrano L, Dorn GW., 2nd Mitochondrial fission and fusion factors reciprocally orchestrate mitophagic culling in mouse hearts and cultured fibroblasts. Cell Metab. 2015;21:273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bombelli F, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2A: from typical to rare phenotypic and genotypic features. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1036–1042. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koshiba T, et al. Structural basis of mitochondrial tethering by mitofusin complexes. Science. 2004;305:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1099793. doi:10.1126/science.1099793 305/5685/858 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Low HH, Lowe J. A bacterial dynamin-like protein. Nature. 2006;444:766–769. doi: 10.1038/nature05312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang P, Galloway CA, Yoon Y. Control of mitochondrial morphology through differential interactions of mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e20655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H, et al. Mitofusins Mfn1 and Mfn2 coordinately regulate mitochondrial fusion and are essential for embryonic development. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;160:189–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211046. doi:10.1083/jcb.200211046 jcb.200211046 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Dorn GW., 2nd PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science. 2013;340:471–475. doi: 10.1126/science.1231031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gong G, et al. Parkin-mediated mitophagy directs perinatal cardiac metabolic maturation in mice. Science. 2015;350:aad2459. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2459. 10.1126/science.aad2459. Epub 2015 Dec 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H, Chomyn A, Chan DC. Disruption of fusion results in mitochondrial heterogeneity and dysfunction. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:26185–26192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503062200. doi:M503062200 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M503062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Detmer SA, Chan DC. Complementation between mouse Mfn1 and Mfn2 protects mitochondrial fusion defects caused by CMT2A disease mutations. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:405–414. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calvo J, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 caused by mitofusin 2 mutations. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:1511–1516. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.284. 10.1001/archneurol.2009.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Detmer SA, Vande Velde C, Cleveland DW, Chan DC. Hindlimb gait defects due to motor axon loss and reduced distal muscles in a transgenic mouse model of Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2A. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:367–375. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picard M, et al. Trans-mitochondrial coordination of cristae at regulated membrane junctions. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6259. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7259. 10.1038/ncomms7259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang J, et al. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat Methods. 2015;12:7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mochly-Rosen D, Das K, Grimes KV. Protein kinase C, an elusive therapeutic target? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2012;11:937–957. doi: 10.1038/nrd3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobieski C, Jiang X, Crawford DC, Mennerick S. Loss of Local Astrocyte Support Disrupts Action Potential Propagation and Glutamate Release Synchrony from Unmyelinated Hippocampal Axon Terminals In Vitro. J Neurosci. 2015;35:11105–11117. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1289-15.2015. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1289-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W, et al. The ALS disease-associated mutant TDP-43 impairs mitochondrial dynamics and function in motor neurons. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:4706–4719. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt319. 10.1093/hmg/ddt319. Epub 2013 Jul 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mackin C, Palacios T. Large-scale sensor systems based on graphene electrolyte-gated field-effect transistors. Analyst. 2016;141:2704–2711. doi: 10.1039/c5an02328a. 10.1039/c5an02328a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qvit N, Disatnik MH, Sho E, Mochly-Rosen D. Selective Phosphorylation Inhibitor of Delta Protein Kinase C-Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase Protein-Protein Interactions: Application for Myocardial Injury in Vivo. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:7626–7635. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02724. 10.1021/jacs.6b02724. Epub 2016 Jun 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Purple is GTPase domain, red is HR1, black is transmembrane domain, green is HR2.

Purple is GTPase domain, red is HR1, black is transmembrane domain, green is HR2.

Purple is GTPase domain, red is HR1, black is transmembrane domain, green is HR2.

Purple is GTPase domain, red is HR1, black is transmembrane domain, green is HR2.

White frames show cropping

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).