Abstract

We report the synthesis and self-assembly of two lipophilic 2′-deoxyguanosine (G) derivatives whose fluorescence intensity is modulated by self-assembly into supramolecular G-quadruplexes (SGQs). Whereas both derivatives self-assemble isostructurally, one shows up to 100% emission enhancement while the other shows initial enhancement, followed by 10% quenching. Thus, the rotational restrictions resulting from self-assembly are enough to induce significant changes in emission, but it is critical to consider the specific interactions between fluorophores since they will determine the ultimate emission signature. These findings could open the door to the development of luminescent supramolecular sensors and probes.

Graphical Abstract

The fluorescence intensity of 8-aryl-2’-deoxyguanosine derivatives enables monitoring the formation of supramolecular G-quadruplexes, opening the door to sensors and probes.

The increasing complexity of both the supramolecular systems under study and the environments where they operate, requires the concomitant development of suitable characterization methods. Absorption and emission spectroscopies are valuable alternatives that have been applied extensively in the study of supramolecular systems. For example, phenomena such as Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)1–3 have enabled studies of precise assemblies4, 5 while aggregation induced emission (AIE)6, 7 is more suitable for polymeric or ill-defined aggregates. These and related strategies have opened the door to studies in complex biological environments and the increasing application of supramolecular systems to address problems of biomedical relevance. 8

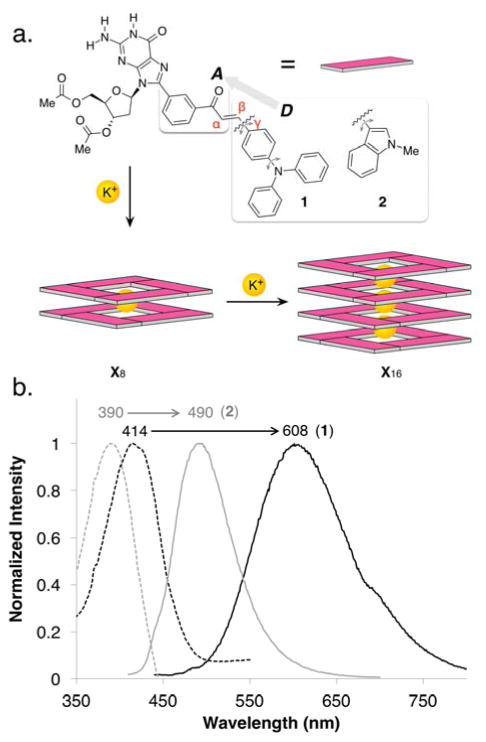

Guanosine (G) and related derivatives are versatile recognition motifs for the development of functional supramolecular nanostructures.9, 10 They self-assemble to form hydrogen-bonded planar tetramers, which upon further stacking (promoted by cations such as K+) lead to supramolecular G-quadruplexes or SGQs (Figure 1). We have developed a family of 8-(m-acetylphenyl)-2′-deoxyguanosine derivatives, where the strategic incorporation of a meta-carbonyl moiety as a hydrogen-bond acceptor leads to the reliable formation of very robust hexadecameric SGQs in both organic and aqueous media.11 This family of derivatives enabled the development of functional supramolecules such as self-assembled dendrimers,12 stimuli-responsive assemblies13–15 and drug carriers.16

Figure 1.

(a) Kekulé representations of derivatives 1 and 2, and schematic depiction of their potassium cation promoted self-assembly into supramolecular G-quadruplexes (SGQs) (X8 and X16). The grey double-headed arrows highlight bonds whose rotations are expected to be restricted by self-assembly. The derivatives were designed to contain an electron donor (D) group to complement the m-carbonyl moiety, which acts as both electron acceptor (A) and inducer for the formation of a hexadecamer. (b) Absorption (dashed line) and emission (solid line) of derivatives 1 (black line) and 2 (grey line) in CH3CN (see Table 1 and Supporting Information for more details).

NMR methods continue to provide an invaluable tool to study the structure and dynamics of SGQs in vitro. However, the study of SGQs in biological environments continues to require the development of compatible alternative methods such as microscopy, to provide a signature for their formation. We have taken advantage of FRET to evaluate the formation of a host-guest complex between a hydrophilic SGQ and the anti-cancer drug doxorubicin.17 Despite its usefulness, FRET and related methods are limited to the study of heteromeric assemblies, or homomeric assemblies made of components labelled with two different dyes.

A number of fluorescent G-derivatives have been reported in recent years as probes for biophysical studies of DNA oligonucleotides,18–22 to study the structure and dynamics of DNA G-quadruplexes,23–25 and to develop biosensors based on aptamers that contain DNA G-quadruplex motifs.26–28 There have also been reports of lipophilic fluorescent G-derivatives, though their emission properties were not used to track self-assembly.29–32 Even with all these efforts, the lack of G-derivatives that show a characteristic luminescence signature as a function of the molecularity of the supramolecular assembly prompted us to perform the present study.

There are two basic strategies for the development of fluorescent G-derivatives: (1) grafting a fluorophore to the structure; or (2) modifying the structure such that it becomes a fluorophore.21,23 Our design incorporates an electron donor (D) moiety conjugated with the meta-carbonyl phenyl group (Figure 1a). The latter acts as both the electron acceptor (A) (to enable intramolecular charge transfer) and a key element that promotes the formation of hexadecameric SGQs in both organic and aqueous media.11 Thus, the complementary D group should maximize the changes in fluorescence while maintaining the attractive interactions to counteract the steric repulsions between the fluorophores. The decrease in degrees of freedom in the supramolecular state, relative to the monomers of 1 and 2, should hinder the internal rotation around the bonds separating the “D” and “A” moieties with a concomitant enhanced emission. This strategy has been effectively implemented in the context of lipid analogues within a membrane, nucleosides covalently attached to nucleic acids, and amino acids analogues incorporated into proteins.21, 33 In here we test the suitability of this strategy in the context of SGQs.

In principle, self-assembly should lead to a more restricted environment, but will it be enough to produce the desired signature emission? Will other interactions affect the emission properties, and if so, to what extent? And while the ultimate goal is to develop hydrophilic fluorescent G-derivatives that give a signature signal upon assembly in biological environments, the lipophilic derivatives described here offer advantages like: (1) simpler synthesis and purification; (2) enable the determination of their inherent changes in luminescence upon self-assembly due to restricted rotations around the fluorophore (i.e., microviscosity),21, 33 with minimal complications due to solvent effects such as changes in the micropolarity surrounding the chromophores.34

The two compounds evaluated in the work presented here provided two sizes and shapes, ranging from the bulkier 135 to smaller 2. Furthermore, both compounds have photophysical properties in the visible part of the spectrum, which is critical for future biological applications, and to minimize competing photoreactions that have been previously reported by us.36

The synthesis of both compounds relied on the reaction of the meta-acetyl group with readily available aldehydes to obtain both G-derivatives 1 and 2 containing chalconyl moieties.37 These derivatives and their intermediates were characterized by standard techniques (e.g., NMR, IR, HRMS).38 1H NMR spectra show that the Claisen-Schmidt condensation leads to the exclusive formation of the trans alkenes, as suggested by the J coupling constants for the olefinic protons that range from 15.2–15.6 Hz. Despite the modifications to the guanine base, the signals corresponding to the ribose sugar are essentially unchanged between derivatives 1 and 2.

Both derivatives 1 and 2 are fluorescent, and showed unusually large Stokes shifts (Figure 1b; Table 1; Figures S15, S16),38 which is associated with a large change between ground and excited state dipoles.39 The particularly high Stokes shift for 1 (194 nm) hints to an excited state charge transfer, a characteristic property of the diphenylamine moiety.34 Large Stokes shifts is a highly desirable feature in fluorescent biological probes as it decreases emission reabsorption.40

Table 1.

Photophysical properties for 1 and 2 in CH3CN.

| λabs | λem | Ss | εc1 | Φfa | Brightness (ε Φ) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 414 | 608 | 194 | 31.5 | 0.03 | 899 |

| 2 | 390 | 490 | 110 | 25.5 | 0.05 | 1352 |

The values for λabs, λem, and Stokes shift (Ss) are in nm, while εc is in 103 M−1cm−1.

Fluorescence quantum yields were determined using perylene (Φf = 0.92 in EtOH) as standard as described in the Supporting Information.11

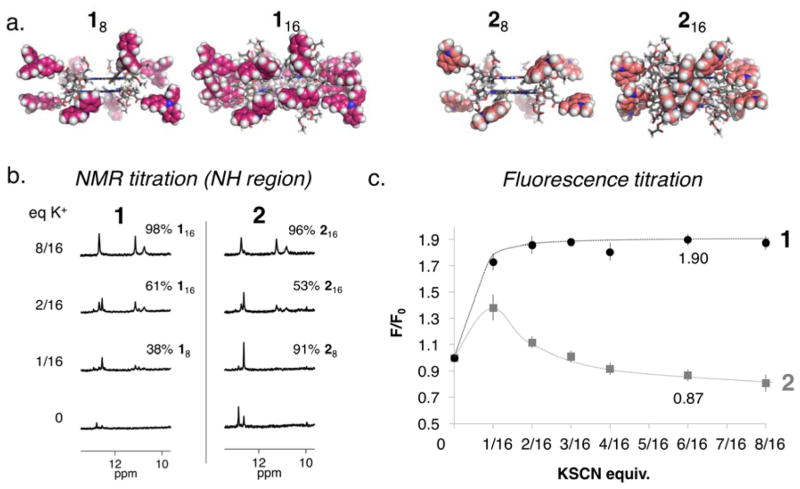

Self-assembly of 1 and 2 was thoroughly characterized through a combination of 1D and 2D NMR, and ESI-MS experiments (Figure S14–S24).38 Titration of the derivatives with KSCN (as the potassium source41) showed the emergence of the signature 1H NMR peaks corresponding to a hexadecameric SGQ (Figures 2b, S17, S20). 2D NOESY experiments also reveal the signature cross-peaks characteristic of a hexadecameric SGQ (Figures 3, S18, S21).38 ESI-MS shows signals corresponding to supramolecular [116•K3]3+ and [216•K3]3+ ions, as well as other species present in the gas phase (Figure S23–S24).

Figure 2.

a) Molecular models showing the arrangements of the fluorophore moieties (depicted in space-filling representations) in 1 and 2, as octamers (18 and 28) and hexadecamers (116 and 216). b) Titration of 1 and 2 with KSCN, monitored by 1H NMR. Spectral window shows the N1-H region, displaying the characteristic peaks of an SGQ. See figures S14–S19 for full spectra. Equivalents of KSCN shown on the left. Percentage of hexadecamer or octamer indicated at the right of each spectrum. c) Fluorescence intensity ratios of 1 and 2 as function of equivalents of KSCN added (ex. wavelength: 500 nm (1) and 450 nm (2), em/ex slit 5 nm, 600V, CH3CN, 5 mM). Measurements done in triplicate. Error bars included for all measurements.

Figure 3.

a) 2D NOESY spectra (CD3CN, 0.5 equiv KSCN) showing selected correlations (in purple) corresponding to the interactions indicated in the model. b) Model showing the relationships for some of the signature cross-peaks seen in the G-quadruplex core.48

The emission intensity of 1 increases steadily with its self-assembly into an octameric SGQ (38% of 18 at 1/16 equiv K+) effectively doubling after the equilibrium has shifted towards the hexadecameric SGQ (98% of 116 at 1/2 equiv K+) (Figure 2b, 2c).38 Computer modelling studies of 18 and 116 reveal that stacking interactions between the (para-diphenylamino)-phenyl fluorophores are hindered by their geometric arrangement and steric bulk (Figure 2a). The rigidity imparted within the SGQ reduces the energy dissipation via non-radiative pathways, thus enhancing the fluorescence emission. These observations are consistent with the behaviour of other fluorescent nucleoside analogues with push-pull fluorophores21, 42 and other molecules exhibiting the AIE phenomenon.7, 43 The freely rotating single bonds in 1 are a requirement for the steady enhancement of fluorescence upon assembly (Figure 1).44

Like 1, the addition of 1/16 equiv of KSCN to a solution of 2 leads to an enhanced fluorescence emission intensity due to the equilibrium shifting from loosely bound aggregates to an octameric SGQ 28 (Figure 2b, 2c). In contrast to 1, however, formation of a hexadecameric SGQ 216 (promoted by further addition of KSCN) leads to a decrease in emission to about 80% of the initial intensity. These results are consistent with a process whereby formation of an octameric SGQ 28 restricts the degrees of freedom of the fluorophores due to enhanced steric crowding, but with minimal stacking interactions between the fluorophores (Figure 2a, right). In the hexadecameric SGQ 216, however, increased steric crowding makes π–π interactions inevitable between the indole moieties with the concomitant emission quenching (Figure 2a, left).

The new family of fluorescent G-derivatives presented here is attractive for a number of reasons: (1) easy synthesis from commercially available aldehydes, making them amenable for the preparation of chemical libraries (as has been reported for biologically active chalcones)45,46,47; (2) self-assembly into precise hexadecameric SGQs; and (3) self-assembly enhanced emission in the visible part of the spectrum with large Stokes shifts. These experiments in organic media enable the isolation of contributions from changes in the microviscosity around the fluorophores as a function of the assembly state, with minimal complications due to the large changes in micropolarity expected from analogous studies in aqueous media. Similar compounds could open the door for the development of luminescent sensors for potassium and other cations. Furthermore, since we have demonstrated that related hydrophilic G-derivatives can self-assemble isostructurally in aqueous environments,11 the findings described here augur well for the future development of supramolecular probes for biological studies. Ongoing studies in our group are aimed toward these goals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the NIH-SCoRE (Grant No. 5SC1GM093994). DSB and LDR thank the NIH-MBRS-RISE Program (2R25GM061151) and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (DSB) for fellowships.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental details, characterization and spectral data (PDF). See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.Lakowicz J. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Springer; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.James JR, Oliveira MI, Carmo AM, Iaboni A, Davis SJ. Nat Methods. 2006;3:1001–1006. doi: 10.1038/nmeth978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benz A, Singh V, Mayer TU, Hartig JS. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:1422–1426. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett ES, Dale TJ, Rebek JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3818–3819. doi: 10.1021/ja0700956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellano RK, Stephen LC, Colin N, Rebek JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7876–7882. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ding D, Li K, Liu B, Tang BZ. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:2441–2453. doi: 10.1021/ar3003464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong Y, Lam JWY, Tang BZ. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:5361–5388. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15113d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma X, Zhao Y. Chem Rev. 2014;115:7794–7839. doi: 10.1021/cr500392w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis JT, Spada GP. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:296–313. doi: 10.1039/b600282j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lena S, Masiero S, Pieraccini S, Spada GP. Chem Eur J. 2009;15:7792–7806. doi: 10.1002/chem.200802506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.García-Arriaga M, Hobley G, Rivera JM. J Org Chem. 2016;81:6026–6035. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rivera LR, Betancourt JE, Rivera JM. Langmuir. 2011;27:1409–1414. doi: 10.1021/la103961m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Betancourt JE, Martín-Hidalgo M, Gubala V, Rivera JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3186–3188. doi: 10.1021/ja809612d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Betancourt JE, Rivera JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:16666–16668. doi: 10.1021/ja9070927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martín-Hidalgo M, Rivera JM. Chem Commun. 2011;47:12485–12487. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14965b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Betancourt JE, Subramani C, Serrano-Velez JL, Rosa-Molinar E, Rotello VM, Rivera JM. Chem Commun. 2010;46:8537–8539. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04063k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rivera JM, Martín-Hidalgo M, Rivera-Ríos JC. Org Biomol Chem. 2012;10:7562–7565. doi: 10.1039/c2ob25913c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matsumoto K, Takahashi N, Suzuki A, Morii T, Saito Y, Saito I. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:1275–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.11.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito Y, Suzuki A, Imai K, Nemoto N, Saito I. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:2606–2609. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinohara Y, Matsumoto K, Kugenuma K, Morii T, Saito Y, Saito I. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:2817–2820. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinkeldam RW, Greco NJ, Tor Y. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2579–2619. doi: 10.1021/cr900301e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tainaka K, Tanaka K, Ikeda S, Nishiza K-i, Unzai T, Fujiwara Y, Saito I, Okamoto A. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4776–4784. doi: 10.1021/ja069156a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vummidi BR, Alzeer J, Luedtke NW. ChemBioChem. 2013;14:540–558. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dumas A, Luedtke NW. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:2044–2051. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dumas A, Luedtke NW. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:18004–18007. doi: 10.1021/ja1079578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manderville RA, Wetmore SD. Chem Sci. 2016;7:3482–3493. doi: 10.1039/c6sc00053c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanchard DJM, Cservenyi TZ, Manderville RA. Chem Commun. 2015;51:16829–16831. doi: 10.1039/c5cc07154b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sproviero M, Manderville RA. Chem Commun. 2014;50:3097–3099. doi: 10.1039/c3cc49560d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.González-Rodríguez D, Janssen PGA, Martín-Rapún R, De Cat I, De Feyter S, Schenning APHJ, Meijer EW. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:4710–4719. doi: 10.1021/ja908537k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martić S, Wu G, Wang S. Inorg Chem. 2008;47:8315–8323. doi: 10.1021/ic800899b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng X, Moriuchi T, Kawahata M, Yamaguchi K, Hirao T. Chem Commun. 2011;47:4682–4684. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10774g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng X, Moriuchi T, Sakamoto Y, Kawahata M, Yamaguchi K, Hirao T. RSC Adv. 2012;2:4359–4363. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haidekker MA, Theodorakis EA. Org Biomol Chem. 2007;5:1669–1678. doi: 10.1039/b618415d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grabowski ZR, Rotkiewicz K, Rettig W. Chem Rev. 2003;103:3899–4032. doi: 10.1021/cr940745l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The triphenylamino motif is also commonly used to prepare luminescent materials; for selected examples see: Shirota Y, Kageyama H. Chem Rev. 2007;107:953–1010. doi: 10.1021/cr050143+.

- 36.Rivera JM, Silva-Brenes D. Org Lett. 2013;15:2350–2353. doi: 10.1021/ol400610x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.For an example of the use of donor-acceptor type chalcones used for cation sensing see: Rurack K, Bricks JL, Reck G, Radeglia R, Resch-Genger U. J Phys Chem A. 2000;104:3087–3109.

- 38.See Supporting Information for details.

- 39.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. 3. Springer; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The long emission wavelengths (ca 610 nm) of derivative 1 are very attractive as red-shifted emitters have better tissue penetrating properties, making them more suitable for in vivo imaging studies, two-photon microscopy Pawlicki M, Collins HA, Denning RG, Anderson HL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:3244–3266. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805257.

- 41.The use of other ions to promote the formation of SGQs has been previously studied by us Cfr Martín-Hidalgo M, García-Arriaga M, González F, Rivera JM. Supramol Chem. 2015;27:174–180. doi: 10.1080/10610278.2014.924626.

- 42.Hopkins PA, Sinkeldam RW, Tor Y. Org Lett. 2014;16:5290–5293. doi: 10.1021/ol502435d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwok RTK, Leung CWT, Lam JWY, Tang BZ. Chem Soc Rev. 2015;44:4228–4238. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00325j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.This is reminiscent of the mechanism by which the GFP’s fluorophore increases its emission through the inhibition non-radiative energy dissipation processes; Sample V, Newman RH, Zhang J. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:2852–2864. doi: 10.1039/b913033k.

- 45.Powers DG, Casebier DS, Fokas D, Ryan WJ, Troth JR, Coffen DL. Tetrahedron. 1998;54:4085–4096. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou B, Xing C. Med Chem. 2015;5:388. doi: 10.4172/2161-0444.1000291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JS, Bukhari SNA, Fauzi NM. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:4761. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S86242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Models were constructed using a methodology similar to that described by us previously; García-Arriaga M, Hobley G, Rivera JM. J Org Chem. 2016;81:6026–6035. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b01113.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.