Abstract

In this issue of Molecular Cell, Gross AM and colleagues (Gross et al., 2016) find a CpG DNA methylation signature in blood cells of patients with chronic well-controlled HIV infection that correlates with accelerated aging

Biological age often differs from chronological age. Some older individuals appear more youthful and are less likely to develop age-related diseases than their age would predict, while some younger individuals prematurely develop age-related conditions. Researchers have searched for biomarkers that correlate with biological age that might act as biological aging clocks. Proposed aging clocks include levels of the steroid dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), tissue accumulation of the auto-fluorescent pigment lipofuscin (Baquer et al., 2009), telomere length, p16INK4a expression levels (Benayoun et al., 2015), and, more recently, CpG DNA methylation (Horvath, 2013). By measuring the methylation status across a large set of CpG sites in blood cells, researchers were able to construct models that predict biological age (Hannum et al., 2013; Horvath, 2013) and show that methylation patterns change prematurely in diseases associated with accelerated aging, such as progeria (Weidner et al., 2014) and Down’s syndrome (Horvath et al., 2015). However, whether this epigenetic signal can be used for more complex diseases with shortened lifespan is uncertain.

Chronic HIV infection, even when viral loads are kept below the level of detection, is associated with early onset of diseases linked to aging, including cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and cancer, and premature death (Deeks, 2011). Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) controls the burden of HIV, without curing the infection, enabling HIV-infected patients to live for many decades, provided they continue their medications. However, even though most viral replication is suppressed, a reservoir of infected cells persists and there is some evidence that viral replication is not completely suppressed. Untreated HIV infection is associated with profound systemic inflammation. Although HAART treatment suppresses much of the inflammation, virally suppressed patients have elevated levels of some pro-inflammatory cytokines even after many years of HAART therapy, suggesting that inflammation is not completely controlled (Deeks, 2011). Persistent inflammation has clearly been linked to accelerated aging in mouse models.

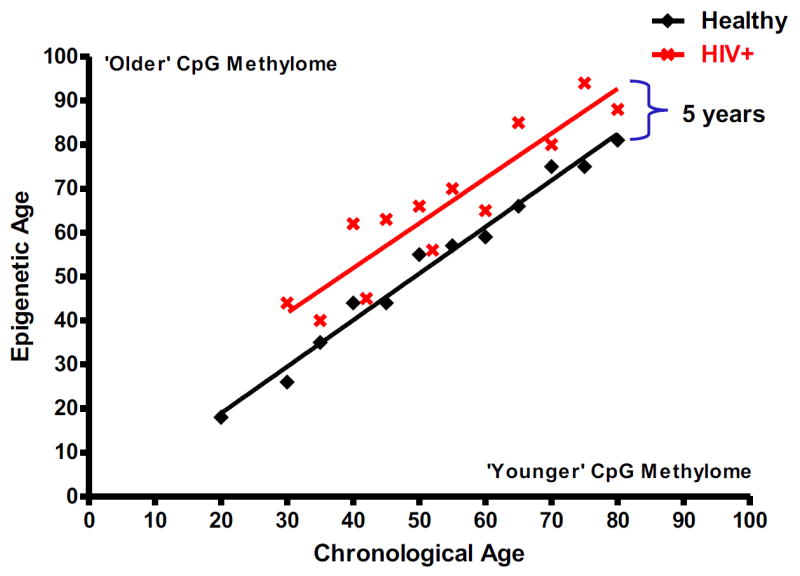

In this issue of Molecular Cell, Andrew Gross and colleagues (Gross et al., 2016), developed and evaluated epigenetic models of aging based on CpG DNA methylation that enabled them to quantify the effects of HIV infection on the rate of aging. More specifically, they compared the patterns of DNA methylation from whole blood samples of 137 HIV-infected HAART-treated males and 44 healthy control individuals. By analyzing a previously validated set of 26,927 age-associated methylation sites, the authors found increased methylation changes in HIV-infected patients beyond their chronological age that suggested about a 5 year increase in aging compared to healthy controls.

Previous epigenetic models (Hannum et al., 2013; Horvath, 2013) predicted chronological age at a population level. Gross and colleagues combined features of both these models to generate a consensus epigenetic model that outperformed either of them, when tested on independent datasets. In addition they further modified their model by incorporating an algorithm that normalizes the methylation patterns based on cell-type composition in the blood. This is particularly important for HIV, as HIV infection reduces CD4+ T cell counts (which constitute a sizeable fraction of nucleated blood cells) in many patients. By applying this new consensus model to HIV-infected donors, Gross et al found an average age acceleration of 4.9 years, both in HAART-treated patients with recent (less than 5 years) or chronic (more than 12 years) HIV infection, suggesting that infection per se rather than the length of time after infection may be linked to accelerated age. These results are in agreement with another study examining the epigenetic age of HAART-treated individuals using brain tissue and blood (7.4 and 5.2 years acceleration respectively) (Horvath and Levine, 2015). Another group found a more severe acceleration of aging (~14 years) by examining methylation patterns from peripheral blood of HIV-infected untreated patients (Rickabaugh et al., 2015). This difference is probably due to the effectiveness of HAART treatment, although the statistical analyses used in these studies were not the same. It will be interesting in the future to take the data from (Rickabaugh et al., 2015) and analyze it with the program developed by (Gross et al., 2016) to determine the extent to which HAART treatment, or when in the course of disease it was started, reduces accelerated aging.

HIV infects both myeloid and lymphoid blood cells and it is likely that hematopoietic stem cells can also be infected. HIV infection also causes chronic activation and increased proliferation of uninfected immune cells. One may thus wonder whether an epigenetic analysis of blood cells is representative of the state of aging of other tissues. In this study, Gross and colleagues compared their methylation analysis in FACS-sorted neutrophils, which are not directly infected, and CD4+ T cells, which are susceptible to infection, using a new cohort of 48 HIV+ and control patients. Although they calculated a 5.7 year increase in biological age of HIV-infected patients based on the CD4 T cell analysis, a much less dramatic effect was observed in neutrophils, suggesting that the aging signature may not apply equally to all cell types. If this method is to be used as a biomarker of aging, it will be important to know how well the signature in the blood correlates with the signature in other tissues. In the future it would be worthwhile to compare the epigenetic state of blood cells in HIV-infected individuals with that of other cells that are not susceptible to infection, such as skin fibroblasts, and to cells from tissues that are prone to diseases associated with accelerated aging, such as the liver or heart. At the same time, to distinguish the consequences of direct blood cell infection from those of chronic inflammation, it would be useful to compare the blood cell epigenetic signature of controlled HIV-infected patients with that of patients who have been infected with other chronic viruses that do not infect blood cells but cause systemic inflammation, such as hepatitis viruses.

In this study, the authors found a subset of methylation changes that correlated with changes observed across aging and another subset, specifically linked to HIV infection. In particular one region appeared to be enriched for methylation changes in response to HIV, independently of aging. This region, consisting of 10 megabases on chromosome 6, had reduced methylation levels in cells from HIV-infected donors. This region contains both histone gene cluster 1 and the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) locus, which encodes for the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins. HLA proteins have important functions in the immune response to HIV infection by presenting antigens to T cells and NK cells. Genetic variations at the HLA locus influence the rate of HIV progression (Fellay et al., 2007). In particular a single nucleotide polymorphism, rs239029, in the HCP5 gene (an endogenous retrovirus) is strongly associated with lower viral levels and a favorable prognosis, although the reason for this association is unknown. Interestingly the hypomethylated CpG sites were concentrated around the HCP5 gene locus, suggesting that its expression and thereby the molecular response to HIV infection may be influenced by CpG DNA methylation of this site.

Several studies in a few diseases have now used C5-methylation signatures as biomarkers of aging. These papers (Gross et al., 2016; Horvath and Levine, 2015; Rickabaugh et al., 2015) have shown that diseases as complex as HIV can be assessed for their effects on aging. As our understanding of chromatin changes that occur with aging grows, the epigenetic clock may be further refined to incorporate additional chromatin modifications. For example, histone methylation has also been shown to change with age or progeria (Benayoun et al., 2015). Other DNA modifications such as the oxidized derivatives of C5-methyl cytosine and N6-adenine methylation could also be incorporated, but their dynamics during aging have yet to be determined. Combining an assessment of these epigenetic marks with CpG methylation might further increase the accuracy of the epigenetic clock for evaluating aging. Since regulating chromatin can alter lifespan in a variety of model organisms (Benayoun et al., 2015), in the future drugs that regulate methylation might be used to slow aging. By accurately determining the biological age of individuals using the epigenetic clock, physicians might be able to develop alternative, more personalized and effective preventive care plans.

Figure 1. Treated HIV infected individuals’ display accelerated aging as assessed by 5mC patterns.

5-methyl cytosine DNA methylation levels across the genome are used to create an epigenetic clock to assess individuals’ age. Blood DNA methylomes of HIV infected HAART treated individuals reveals a ~5 year acceleration of aging.

References

- Baquer NZ, Taha A, Kumar P, McLean P, Cowsik SM, Kale RK, Singh R, Sharma D. Biogerontology. 2009;10:377–413. doi: 10.1007/s10522-009-9226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benayoun BA, Pollina EA, Brunet A. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:593–610. doi: 10.1038/nrm4048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SG. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:141–155. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-042909-093756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellay J, Shianna KV, Ge D, Colombo S, Ledergerber B, Weale M, Zhang K, Gumbs C, Castagna A, Cossarizza A, et al. Science. 2007;317:944–947. doi: 10.1126/science.1143767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross AM, Jaeger PA, Kreisberg JF, Licon K, Jepsen KL, Khosroheidari M, Morsey BM, Shen H, Flagg K, Chen D, et al. Mol Cell. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannum G, Guinney J, Zhao L, Zhang L, Hughes G, Sadda S, Klotzle B, Bibikova M, Fan JB, Gao Y, et al. Mol Cell. 2013;49:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R115. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, Garagnani P, Bacalini MG, Pirazzini C, Salvioli S, Gentilini D, Di Blasio AM, Giuliani C, Tung S, Vinters HV, et al. Aging Cell. 2015;14:491–495. doi: 10.1111/acel.12325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath S, Levine AJ. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:1563–1573. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickabaugh TM, Baxter RM, Sehl M, Sinsheimer JS, Hultin PM, Hultin LE, Quach A, Martinez-Maza O, Horvath S, Vilain E, et al. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidner CI, Lin Q, Koch CM, Eisele L, Beier F, Ziegler P, Bauerschlag DO, Jockel KH, Erbel R, Muhleisen TW, et al. Genome Biol. 2014;15:R24. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]