Abstract

Children and adolescents with long-term physical conditions (LTPCs) are at greater risk of developing psychosocial problems. Screening for such problems may be undertaken using validated psychometric instruments to facilitate early intervention. A systematic review was undertaken to identify clinically utilized and psychometrically validated instruments for identifying depression, anxiety, behavior problems, substance use problems, family problems, and multiple problems in children and adolescents with LTPCs. Comprehensive searches of articles published in English between 1994 and 2014 were completed via Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane CENTRAL databases, and by examining reference lists of identified articles and previous related reviews. Forty-four potential screening instruments were identified, described, and evaluated against predetermined clinical and psychometric criteria. Despite limitations in the evidence regarding their clinical and psychometric validity in this population, a handful of instruments, available at varying cost, in multiple languages and formats, were identified to support targeted, but not universal, screening for psychosocial problems in children and adolescents with LTPCs.

Keywords: screening, depression, anxiety, children, adolescents, chronic illness

Introduction

More than 10% of children and adolescents worldwide are affected by long-term physical conditions (LTPCs), including asthma, diabetes, and epilepsy.1 These individuals are more prone to a range of psychosocial problems including depression, anxiety disorders, behavior disorders, and posttraumatic disorder.1-9 The prevalence of formal psychiatric disorder in children with LTPCs is estimated at between 29% and 34%,10 and pediatricians often lack the confidence to identify such disorders.11 Medical complications of psychiatric problems include poorer treatment adherence, increased hospitalization, and the development of long-term complications.12,13 Although some studies have shown that children with LTPCs such as cancer can cope well,14,15 others have shown they experience more emotional and behavioral problems, even following the completion of treatment.16

Children with LTPCs often minimize distress when asked directly, and parental depression, which is more common in such families, can contribute to the underreporting of children’s mental health symptoms by caregivers.17-20 Symptoms of psychological problems in these children are likely to overlap not just with each other but also with those of their physical conditions.21,22 For instance, somatic symptoms such as low energy, loss of appetite, and difficulty getting to sleep can be both features of depression and side-effects of chemotherapy. Even subclinical psychological symptoms in children with LTPCs can be associated with significant emotional and relational problems.23 Early intervention requires the timely identification of psychosocial problems.24 Despite World Health Organization criteria25 being fulfilled for the screening of many such problems in this population, there are no well-known formal screening programs for identifying psychosocial difficulties in children and adolescents with LTPCs. Currently, psychosocial screening is often undertaken in pediatric settings using nonvalidated techniques such as HEEADSSS assessment.26 Over the past few decades, a number of psychometric instruments have been developed to identify problems in single or multiple psychosocial domains. Many of these have been used in children with LTPCs, but their psychometric properties with this group have not formally been evaluated.10

Previous reviews of psychometric instruments for identifying psychosocial problems in children and adolescents have focused on the clinical utility and psychometric properties of such instruments in the general population. Given that children and adolescents with LTPCs are a higher risk group and that cutoff scores designed for use with the general population may lead to an over- or underestimation of true rates of problems in this cohort, this systematic review was undertaken to identify psychometric instruments that have been used in studies of children and adolescents with LTPCs and to assess their utility as screening tools from both clinical and psychometric viewpoints. Specifically, this review was designed to identify suitable instruments for identifying (a) depression, (b) anxiety, (c) behavior problems, (d) substance use problems, (e) family problems, and (f) multiple problems in this clinical population.

Methods

Literature Search Strategy

Articles detailing the use of psychometric instruments for either identifying or measuring change in one or more of the 6 types of psychosocial problems mentioned above, that had been published in English between 1994 and 2014, were sourced via Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and Cochrane CENTRAL databases accessed between December 20 and 31, 2014 (see the appendix); from reference lists of articles identified from the database searches; and from previous reviews of psychometric instruments for use with children and adolescents.27,28 Abstracts were reviewed by 2 authors (HT and HM), and complete articles were reviewed and a subset identified for data extraction and analysis by all 4 authors (HT, HM, KM, and KG). The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO on January 19, 2015 (Registration Number: CRD42015016021).

Evaluation of Instruments

Psychometric instruments were compared on the basis of clinical properties, including the type of LTPCs with which they had been tested, the time required for completion, available formats, and cost for their use. In addition, they were compared according to their psychometric properties within the child and adolescent LTPC population. Based on the recommendations of previous studies,27-29 the “ideal screening instrument” for each condition was expected to have been tested against a gold standard for screening or identifying cases of psychological disorder in one or more populations of children and adolescents with LTPCs (either an in-depth sophisticated clinical interview with an empathic and experienced interviewer or a scale that had been demonstrated to be as good as such an interview). It was also expected to possess good sensitivity (the probability of having a positive test result among those patients who have a positive diagnosis), specificity (the probability of having a negative test result among those patients who have a negative diagnosis), positive predictive value (the probability of having a positive diagnosis among those patients having a positive test result), and negative predictive value (the probability of having a negative diagnosis among those patients having a negative test result). Finally, it was expected to have good validity (eg, internal consistency Cronbach’s α > 0.829) and reliability (eg, interrater reliability > 0.430) and clear cut points for case identification in children and adolescents with LTPCs. As a meta-analysis was not planned, no formal assessment of risk of bias was undertaken.

Results

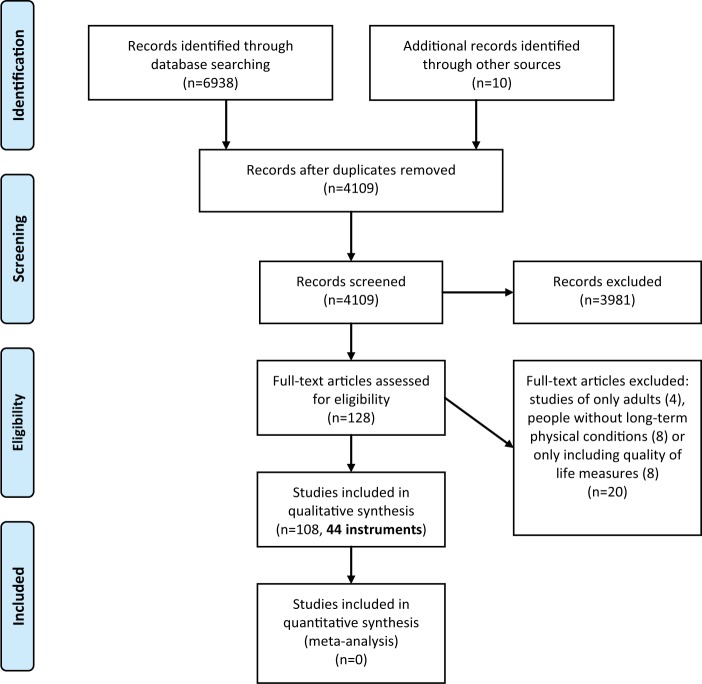

Results are presented in accordance with PRISMA guidelines.31 A total of 4105 abstracts were extracted and reviewed using the search strategy described above, and 57 potential screening instruments were identified (Figure 1). Of these, 13 instruments were subsequently excluded as they were found to either have been used only in children without LTPCs or adult populations, or because they only included quality of life measures. Forty-four suitable scales were evaluated as outlined in Table 1. Further details regarding these scales can be found via the manuals and websites listed in Table 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Table 1.

Clinical and Psychometric Properties of Identified Instruments.

| Name: Author, Year | Description: (a) Number of Items (Subscalesa); (b) Completed by C/P/T/CL/TAb; (c) Languages -Eng/Spa/Fre/Ger/Other (Number)c; (d) Electronic Version—C/W/Nild; (e) Google Scholar Citationse |

Conditions Identified

|

Clinical Properties: (a)Age Range (years); (b) Time to Complete (Minutes); (c) Cost per Use | Psychometric Properties in Children and Adolescents With LTPCs: (a) Sens/Spec/PPV/NPV/Validity (α > 0.8)/Reliability (IRR > 0.4); (b) Validated Against Gold Standard—Yes/No; (c) Clear Cut Point for Case Identification—Yes/No | Use With Children and Adolescents With LTPCs: (a) Conditions; (b) Ages of Participants (Range or Mean in Years); (c) Used for Identification (ID) or Measuring Change (C) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | Behavior | Substance | Family | |||||

| Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI); Beck, Epstein, Brown, Steer, Kazdin (1998)60 | (a) 21 (0) (b) C, TA (c) Eng, Spa (d) C, W (e) 34 506 |

X | (a) 17-80 (b) 5-10 (c) US$3.88 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Asthma121

(b) 16-21 (c) ID |

||||

| Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition (BASC-2); Reynolds, Kamphaus (2004)32 | (a) TRS = 105-165 items, PRS = 139-175 items, self-report = 30 minutes (5s) (b) C, P, T, CL (c) Eng (d) C (e) 3113 |

X | X | X | (a) 2-5; 6-11; 12-21 (b) 10-20 (c) US$3.97 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia,122 medulloblastoma,123 recurrent abdominal pain124

(b) 2-21 (c) ID |

||

| Beck Depression Inventory–Revision (BDI-II); Beck, Steer, Brown (1996)33 | (a) 21 (0) (b) C, TA (c) Eng, Spa (d) C, W (e) 1569 |

X | (a) 13-80 (b) 5 (c) US$2.08 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Asthma,121 beta-thalassemia,125 cancer,126 primary dysmenorrhea,127 polycystic ovarian syndrome,128 various (asthma, diabetes, epilepsy)129

(b) 8-21 (c) ID |

||||

| Beck Depression Inventory–Fast Screen (BDI-FS); Beck, Steer, Brown (2000)34 | (a) 7 (0) (b) C (c) Eng, Spa (d) Nil (e) 6 |

X | (a) 13-80 (b) 5 (c) US$1.16 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Cancer130

(b) 16-30 (c) ID |

||||

| Brief Symptom Inventory–18 (BSI-18); Derogatis (2001)35 | (a) 18 (3s) (b) C (c) Eng, Spa (d) C, W (e) 4649 |

X | (a) >18 (b) 4 (c) US$2.08 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Asthma,121 cancer,131 cancer,132 irritable bowel syndrome133

(b) 14-39 (c) ID + C |

||||

| Beck Youth Inventories (BYI-II); Beck, Beck, Jolly (2001)36 | (a) 20 (5s) (b) C (c) Eng (d) Nil (e) 342 |

X | X | X | (a) 7-18 (b) 5-10 per scale (×5) (c) US$9.14 (for all 5) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Asthma,134 brain tumours135

(b) 7-18 (c) ID + C |

||

| Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL); Achenbach (1991)37 | (a) 100 (1.5-5 y/o = 7s empirical, 5s DSM-related; 6-18 y/o = 8s empirical, 6s DSM-related) (b) P (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Spa, Other (84) (d) C, W (e) 13 013 |

X | X | X | (a) 1.5-5; 6-18 (b) 10-15 (c) US$1.80 |

(a) Sens = 36, Spec = 91, PPV = 80, NPV = 58, Val = N/A, Rel = N/A (b) Yes (c) No |

(a) 22q11.2 deletion syndrome,136 acute leukaemia,137 acute lymphoblastic leukaemia,138 asthma,139 asthma,140 asthma,141 asthma,142 bladder exstrophy and epispadias,143 brain tumours,144 cancer,126 cancer,145 cerebellar astrocytoma,134 cloacal exstophy,146 congenital heart disease,147 congenital heart disease,148 congenital heart disease,149 congenital heart disease,150 craniofacial anomalies,151 diabetes,152 diabetes,153 encopresis,154 encopresis,155 epilepsy,156 epilepsy,157 epilepsy,158 epilepsy,159 juvenile idiopathic arthritis,160 Kawasaki disease,161 kidney disease,162 kidney disease,163 liver transplant patients,164 liver transplant patients,165 liver transplant patients,166 lung transplant patients,167 phenylketonuria,168 port wine stains,169 Prader-Willi syndrome,170 various (asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis),171 various (asthma, cystic fibrosis, hematological/oncological conditions),172 various (asthma, diabetes, epilepsy),129 various (diabetes, epilepsy),173 various (asthma, coeliac disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, Friedriech’s ataxia, arthrogryposis/visual impairment, lymphedema)174

(b) 0-20 (c) ID + C |

||

| Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ); Rothbart, Ahadi, Hershey (1994)68 | (a) 191 (15s) (b) P (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Spa, Other (16) (d) Nil (e) 1445 |

X | (a) 3-7 (b) 60 (c) Available for research on request |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Sickle cell disease175

(b) 7-14 (c) ID |

||||

| Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist-Revision 1 (CCSC-R1*); Ayers, Sandler (1999)38 | (a) 54 (13s) (b) C (c) Eng (d) Nil (e) 38 |

X | (a) N/A (b) N/A (c) N/A |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Various (asthma, coeliac disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, Friedreich’s ataxia, arthrogryposis/visual impairment, lymphedema)174

(b) 10-14 (c) ID + C |

||||

| Children’s Depression Inventory 2 (CDI, now CDI-2); Kovacs (1980)39,85 | (a) 28 (4s) (b) C, P, T (c) Eng, Spa (d) C, W (e) 2161 |

X | (a) 7-17 (b) 5-15 (c) US$6.60 |

(a) Sens = 27, Spec = 95, PPV = 84, NPV = 57, Val = N/A, Rel = N/A (b) Yes (c) No |

(a) 22q11.2 deletion syndrome,176 alopecia,177 asthma,141 cancer,126 cancer,178 childhood cancer survivors,179 diabetes,180 diabetes,153 diabetes,181 epilepsy,156 epilepsy,182 familial Mediterranean fever,183 hepatitis B,184 kidney disease,185 lung transplant patients,167 obesity,186 psoriasis,187 recurrent abdominal pain,188 systemic lupus erythematosus,189 vitiligo,190 various (cancer, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, others),191 various (asthma, diabetes, cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease, Friedreich’s ataxia, arthrogryposis/visual impairment, lymphedema)174

(b) 5-20 (c) ID + C |

||||

| Children’s Depression Rating Scale–Revised (CDRS-R); Poznanski, Cook, Carroll (1979)40 | (a) 17 (0) (b) CL (c) Eng, Ger, Other (1) (d) Nil (e) 442 |

X | (a) 6-12 (b) 15-20 (c) US$2.00 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Sickle cell disease192

(b) 6-18 (c) ID |

||||

| The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D, now CESD-R*); Radloff (1979)41 | (a) 20 (9g) (b) C, CL (c) Eng (d) Nil (e) 355 |

X | (a) Able to read/use a computer (b) 5-10 (c) Available free of charge online |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Central adrenal insufficiency,193 congenital heart disease194

(b) 12-25 (c) ID + C |

||||

| Conners (now Conners 3); Conners, Wells, Parker, Sitarenios, Diamond, Powell (1997)69 | (a) 324 (99 (C), 110 (P), 115 (T)) (17s) (b) C, P, T, CL (c) Eng, Spa (d) C, W (e) 2188 |

X | (a) 6-18 (b) 20 (c) US$10.61 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Diabetes195

(b) 6-16 (c) ID |

||||

| Childhood Psychopathology Measurement Schedule (CPMS); Malhotra, Varma, Verma, Malhotra (1998)42 | (a) 75 (8g) (b) C, CL (c) Eng, Other (1) (d) Nil (e) 58 |

X | X | X | (a) 4-14 (b) N/A (c) N/A |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Atopic dermatitis,196 acute lymphoblastic leukaemia197

(b) 3-19 (c) ID |

||

| The Development and Well-Being Assessment (DAWBA); Goodman, Ford, Richards, Gatward, Meltzer (2000)43 | (a) 118 sides of paper (0) (b) C, P, T, TA (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Other (17) (d) W (e) 818 |

X | X | X | (a) 5-16 (b) 90 (c) Paper version downloadable free of charge (for noncommercial purposes) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Recurrent headache and abdominal pain198

(b) 5-17 (c) ID |

||

| Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA); Herjanic, Reich (1982)44 | (a) Variable, >1600 (18g) (b) CL, TA (c) Eng (d) C (e) 993 |

X | X | X | X | X | (a) 6-17 (b) 60-120 (c) US$1000 (software only), paper price to be determined |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) 22q11.2 deletion syndrome136

(b) 12 (M) (c) ID |

| Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-IV); Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, et al (2000)45a) | (a) ~3000 (6d) (b) C, CL, TA (c) Eng, Spa (d) C (e) 2407 |

X | X | X | X | (a) 6-17 (b) Up to 120 (c) ~US$700 (for installation of computer version) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Asthma,199 asthma,200 asthma,201 Duchenne muscular dystrophy,202 various (diabetes, sickle cell disease)203

(b) 5-23 (c) ID |

|

| Dominic Interactive (DI); Valla, Bergeron, Berube, Gaudet, St-Georges (1994)46 | (a) 91 (7g) (b) C (c) Eng (d) C (e) 38 |

X | X | X | (a) 6-11 (b) 15 (c) US$6.00 (requires $50 one-off program fee in addition) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Recurrent headache204

(b) 6-11 (c) ID |

||

| Family Adaptation and Cohesion Scales (FACES III, now FACES IV); Olson, Portner, Lavee (1985)72 | (a) 62 (6s) (b) C, P (c) Eng, Fre, Gre, Spa, Other (4) (d) Nil (e) 206 |

X | (a) ≥12 (b) N/A (c) US$95 (package) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Diabetes205

(b) 1-14 (c) ID + C |

||||

| McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD); Epstein, Baldwin, Bishop (1983)73 | (a) 60 (7s) (b) C, P (c) Eng, Fre, Spa (d) Nil (e) 2476 |

X | (a) ≥13 (b) 15-20 (c) Available free of charge on application to the authors |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia122

(b) 2-10 (c) ID |

||||

| Family Environment Scale (FES); Moos (1975)74 | (a) 90 (10s) (b) C, P (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Spa, Other (18) (d) W (e) 4228 |

X | (a) ≥11 (b) 15-20 (c) US$2.00 (minimum purchase 50) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Chronic encopresis,155 kidney disease,162 various (asthma, diabetes, cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease, Friedreich’s ataxia, arthrogryposis/visual impairment, lymphedema)174

(b) 2-18 (c) ID + C |

||||

| Feetham’s Family Functioning Survey (FFFS); Roberts, Feetham (1982)75 | (a) 26 (3s) (b) P (c) Eng, Other (2) (d) Nil (e) 122 |

X | (a) >18 (parents only) (b) 10 (c) Japanese and Chinese versions available free of charge |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

Various (asthma, leukemia, cardiac conditions, others)205

(b) 1-17 (c) ID + C |

||||

| General Health Questionnaire–28 (GHQ-28); Goldberg (1972)47 | (a) 28 (4s) (b) C (c) Eng, Other (38) (d) Nil (e) 4130 |

X | X | X | X | (a) ≥18 (b) 3-8 (c) US$4.98 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Diabetes,206 various (asthma, epilepsy)207

(b) 1-25 (c) ID + C |

|

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Zigmoid, Snaith (1983)48 | (a) 14 (2s) (b) C (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Other (11) (d) W (e) 22 082 |

X | X | (a) ≥17 (b) 2-5 (c) US$0.95 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Cystic fibrosis208

(b) 15(M) (c) ID |

|||

| The Hopkins Symptom Checklist 25 (HSCL25); Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, Covi (1984)49 | (a) 25 (5g) (b) CL (c) Eng, Other (1) (d) Nil (e) 3707 |

X | (a) N/A (b) 60-90 (c) N/A |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Diabetes209

(b) 6-18 (c) ID |

||||

| The Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia–Present and Lifetime (K-SADS-PL); Kaufman, Birmaher, Brent, et al (1996)50 | (a) 82 + 5 diagnostic supplement modules (0) (b) CL (c) Eng, Other (1) (d) Nil (e) 4883 |

X | X | X | (a) 6-18 (b) 45-75 (c) Available free of charge for most purposes |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) 22q11.2 deletion syndrome,136 cerebral palsy,210 epilepsy,211 epilepsy,159 recurrent abdominal pain,188 various (chronic fatigue syndrome, juvenile idiopathic arthritis)212

(b) 5-18 (c) ID + C |

||

| Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC, now MASC-2*); March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, Conners (1997)61 | (a) 100 (7s) (b) C, P (c) Eng (d) C, W (e) 1724 |

X | (a) 8-19 (b) 15 (c) US$4.40 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Epilepsy,156 systemic lupus erythematosus189

(b) 8-17 (c) ID |

||||

| The Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ); Angold, Costello, Messer, Pickles, Winder (1995) 51 | (a) 33 (0) (b) C, P (c) Eng (d) Nil (e) 43 |

X | (a) 8-18 (b) 5-10 (c) Available free of charge online |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Heart/lung transplant patients,213 heart/lung transplant patients149

(b) 0-17 (c) ID |

||||

| Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT, now PAT 2.0); Kazak, Prusak, McSherry, Simms, Beele, Rourke, Alderfer, Lange (2001)53 | (a) 69 (7s) (b) P (c) Eng, Spa, Others (N/S) (d) C (e) 84 |

X | X | X | (a) <18 (b) 10 (c) Available free of charge on request from the authors |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Cancer,107 survivors of childhood cancer,108 congenital heart disease,109 inflammatory bowel disease,111 kidney transplant patients,112 sickle cell disease214

(b) 0-18 (c) ID |

||

| Pediatric Symptom Checklist (PSC); Jellinek, Murphy (1988)53 | (a) 35 (3s) (b) C, P (c) Eng, Fre, Spa, Ger, Other (17) (d) W (e) 260 |

X | X | X | (a) 4-16 (b) 10 (c) Available free of charge online |

(a) Sens = 36, Spec = 95, PPV = 88, NPV = 60, Val = N/A, Rel = N/A (b) Yes (c) No |

(a) Various (unspecified)215

(b) 4-15 (c) ID |

||

| UCLA Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index for DSM-IV (PTSD RI); Steinberg, Brymer, Decker, Pynoos (2004)62 | (a) 22 (1d) (b) C (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Spa, Other (12) (d) Nil (e) 64 |

X | (a) 6-18 (b) 20 (c) US$1.00 for 1 software license (minimum software licenses 25) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Traumatic physical injury216

(b) 12-18 (c) ID |

||||

| Revised Behavior Problem Checklist (RBPC); Quay, Peterson (1987)70 | (a) 89 (6s) (b) P, T (c) Eng (d) Nil (e) 531 |

X | (a) 5-18 (b) 20 (c) US$4.40 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy217

(b) N/S (c) ID |

||||

| Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale, Second Edition (RCMAS-2); Reynolds, Richmond (1985)63 | (a) 49 (5s) (b) C (c) Eng, Spa (d) Nil (e) 1501 |

X | (a) 6-19 (b) 10-15 (c) US$2.00 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) 22q11.2 deletion syndrome,176 asthma,141 various (asthma, diabetes, cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease, Friedreich’s ataxia, arthrogryposis/visual impairment, lymphedema)174

(b) 5-18 (c) ID + C |

||||

| Self-administered Psychiatric Scales for Children and Adolescents (SAFA); Cianchetti, Fascello (2001)54 | (a) 174 (6s) (b) C (c) Other (1) (d) Nil (e) 14 |

X | X | (a) 8-18 (b) 30-60 (c) N/A |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Childhood obesity186

(b) 9(M) (c) ID |

|||

| Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED); Birmaher, Khetarpal, Brent et al (1997)64 | (a) 41 (5s) (b) C, P (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Spa, Other (5) (d) C, W (e) 1194 |

X | (a) 8-18 (b) 10 (c) Available free of charge online |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Asthma,60 polycystic ovarian syndrome,128 recurrent abdominal pain124

(b) 7-19 (c) ID + C |

||||

| Semistructured Clinical Interview for Children and Adolescents (SCICA); Achenbach, McConaughy (1994)55 | (a) 224 (18s) (b) C, TA (c) Eng, Far, Other (2) (d) W (e) 7 |

X | X | X | (a) 6-18 (b) 60-90 (c) US$1.80 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Asthma,140 chronic kidney disease162

(b) 6-15 (c) ID |

||

| Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R); Derogatis (1992)56 | (a) 90 (9y) (b) C (c) Eng, Fre, Spa (d) C, W (e) 239 |

X | X | (a) ≥13 (b) 12-15 (c) US$3.05 |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Central adrenal insufficiency,193 lung transplant patients,167 recurrent abdominal pain124

(b) 5-25 (c) ID + C |

|||

| Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ); Goodman (1997)57 | (a) 25 (5s) (b) C, P, T (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Spa, Other (77) (d) C, W (e) 6196 |

X | X | X | X | (a) 4-17 (b) 5 (c) Available free of charge online |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Adenotonsillar hypertrophy,218 asthma,219 asthma,220 cerebral palsy,210 epilepsy,221 Kawasaki disease,162 kidney transplant patients,222 nephrotic syndrome,223 polycystic ovarian syndrome,128 recurrent headache and abdominal pain,198 various (asthma, cerebral palsy, diabetes, epilepsy, obesity)224

(b) 3-18 (c) ID |

|

| State Trait Anxiety Inventory– Children (STAI-C); Spielberger, Edwards (1973)65 | (a) 40 (2s) (b) C, TA (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Spa, Other (23) (d) C (e) 891 |

X | (a) ≥9 (b) 20 (c) US$2.00 (minimum purchase 50) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Cancer,179 cancer,126 encopresis,152 epilepsy,182 heart disease,194 hepatitis B,183 kidney disease,225 psoriasis,187 vitiligo,190 various (asthma, diabetes, spina bifida),226 various (asthma, heart disease, muscular dystrophy, others),205 various (alopecia areata, epilepsy),177 various (cancer, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease, others)191

(b) 1-20 (c) ID + C |

||||

| Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale (TMAS); Taylor (1953)66 | (a) 38 (0) (b) C (c) Eng (d) W (e) 3313 |

X | (a) N/A (b) 10-15 (c) Available free of charge online |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Dysmenorrhea127

(b) 14-20 (c) ID |

||||

| The Vernon Post Hospital Behavior Questionnaire (VPHQ); Vernon, Schulman, Foley (1966)58 | (a) 25 (6s) (b) P (c) Eng (d) Nil (e) 313 |

X | X | X | (a) N/A (b) N/A (c) N/A |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Various (asthma, heart disease, muscular dystrophy, others)205

(b) 1-17 (c) ID + C |

||

| Youth Asthma-Related Anxiety Scale (YAAS); Bruzzese, Unikel, Shrout, et al (2011)67 | (a) 9 (2s) (b) C, P (c) Eng, Spa (d) Nil (e) 5 |

X | (a) N/A (b) N/A (c) N/A |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Asthma63

(b) 10-16 (c) ID |

||||

| Youth Self-Report (YSR); Achenbach (1987)59 | (a) 112 (14s) (b) C (c) Eng, Fre, Ger, Spa, Other (70) (d) C, W (e) 3691 |

X | X | X | (a) 11-18 (b) 15 (c) US$60 (minimum purchase 50) |

(a) N/A (b) No (c) No |

(a) Bladder exstrophy and epispadias,222 congenital heart disease,148 congenital heart disease,150 chronic headache,227 lung transplant patients,167 various (asthma, cancer, diabetes, others),228 various (asthma, cystic fibrosis, hematologic/oncological conditions),172 various (asthma, diabetes, epilepsy)129

(b) 5-20 (c) ID |

||

Abbreviations: C, change; ID, identification; IRR, interrater reliability; M, mean; N/A, not applicable; NPV, negative predictive value; N/S, not stated; PPV, positive predictive value; Sens, sensitivity; Spec, specificity.

Newer version available.

Subscales: s, subscale; d, domain; g, symptom group.

Completion of instrument: C, child/adolescent/patient; P, parent/caregiver (may include family members ≥12 years of age); T, teacher/childcare provider; CL, clinician; TA, trained administrator (may or may not be a clinician, teacher).

Languages: Eng, English; Fre, French; Ger, German; Spa, Spanish; Other, other languages (details available via authors).

Online completion: C, computer-based scoring available; W, website-based scoring available; Nil, not available.

Citation numbers: Relate to the version used in the identified studies, not previous or subsequent versions.

Table 2.

Key Websites or References for Identified Instruments.

| Instrument | Website or Reference |

|---|---|

| BAI | Beck Anxiety Inventory [Internet]. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Clinical; ©2015 [Cited December 13, 2015]. Available from: http://www.pearsonclinical.com/psychology/products/100000251/beck-anxiety-inventory-bai.html#tab-training |

| BASC-2* | Behavior Assessment System for Children, Third Edition (BASC-3) [Internet]. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Clinical; ©2015 [Cited December 13, 2015]. Available from: https://www.pearsonclinical.com.au/products/view/566#pricing=&tabs=0 |

| BDI-II | Beck Depression Inventory [Internet]. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Clinical; ©2015 [Cited December 13, 2015]. Available from: http://www.pearsonclinical.com/psychology/products/100000159/beck-depression-inventoryii-bdi-ii.html |

| BDI-FS | Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-Fast Screen for Medical Patients: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 200034 |

| BSI 18 | Brief Symptom Inventory 18 [Internet]. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Clinical; ©2015 [Cited December 13, 2015]. Available from: http://www.pearsonclinical.com/psychology/products/100000638/brief-symptom-inventory-18-bsi-18.html |

| BYI-II | Beck Youth Inventories–Second Edition (BYI-II) [Internet]. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Clinical; ©2015 [Cited December 13, 2015]. Available from: http://www.pearsonclinical.com/psychology/products/100000153/beck-youth-inventories-second-edition-byi-ii.html# |

| CBCL | Child Behavior Checklist [Internet]. Burlington, VT: ASEBA; ©2015 [Cited December 14, 2015]. Available from: http://www.aseba.org/ |

| CBQ | Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Dev. 2001;72(5):1394-1408. |

| CCSC-R1 | Camisasca E, Caravita SCS, Milani L, et al. The Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist–Revision 1: a validation study in the Italian population. TPM Test Psychom Methodol Appl Psychol. 2012;19(3):197-218. |

| CDI 2 | Kovacs M. [Internet]. Cheektowaga, NY: Multi-Health Systems; ©2004-2015 [Cited December 14, 2015]. Available from: http://www.mhs.com/product.aspx?gr=edu&id=overview&prod=cdi2 |

| CES-D* | Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. [Internet]. Torrance, CA: WPS; ©2015 [Cited December 14, 2015]. Available from: http://www.wpspublish.com/store/p/2703/childrens-depression-rating-scale-revised-cdrs-r#purchase-product |

| CDRS-R | The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale. [Internet]. San Clemente, CA: Center for Innovative Public Health Research; ©2015 [Cited December 14, 2015]. Available from: http://cesd-r.com/cesdr/ |

| Conners* | Conners 3 [Internet]. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Clinical; ©2015 [Cited December 14, 2015]. Available from: https://www.pearsonclinical.com.au/products/view/92#tabs=0 |

| CPMS | Malhotra S, Varma VK, Verma SK, et al. Childhood psychopathology measurement schedule: development and standardization. Indian J. Psychiatry. 1988;30(4):325-331. |

| DAWBA | DAWBA [Internet]. London, England: youthinmind; ©2009 [Cited December 14, 2015]. Available from: http://www.dawba.info/a0.html |

| DICA | Reich W, Welner Z, Herjanic B. [Internet]. Melbourne, Australia: Psych Press; ©2016 [Cited January 8, 2016]. Available from: http://www.psychpress.com.au/Psychometric/product-page.asp?ProductID=88#expand |

| DISC-IV | Fisher P, Lucas L, Lucas C, Sarsfield, Shaffer D. [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; ©2006 [Cited December 14, 2015]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/limited_access/interviewer_manual.pdf |

| DI | Dominic Interactive [Internet]. Westmount, Canada: Dominic Interactive; ©2009 [Cited December 14, 2015]. Available from: http://www.dominic-interactive.com/index_en.jsp |

| FACES III | FACES IV [Internet]. Minneapolis, MN: Life Innovations, Inc; ©2006 [Cited December 15, 2015]. Available from: http://www.facesiv.com/

Family Adaptability and Cohesion Scale [Internet]. Los Angeles, CA: The National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; ©2014 [Cited December 15, 2015]. Available from: http://www.nctsn.org/content/family-adaptability-and-cohesion-scale |

| FAD | Family Assessment Device [Internet]. Los Angeles, CA: The National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; ©2013. [Cited December 15, 2015]. Available from: http://www.nctsn.org/content/family-assessment-device |

| FES | Moos BS, Moos RH [Internet]. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden Inc; ©2002 [Cited December 15, 2015]. Available from: http://www.mindgarden.com/96-family-environment-scale#horizontalTab1 |

| FFFS | Roberts CS, Feetham SL. Assessing family functioning across three areas of relationships. Nurs Res. 1982;31(4):231-235. Family Nursing [Internet]. Kobe, Japan: Family Health Care Nursing; ©2013 [Cited December 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.familynursing.org/fffs/ |

| GHQ-28 | General Health Questionnaire [Internet]. London, England: GL-Assessment; ©2015 [Cited December 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.gl-assessment.co.uk/products/general-health-questionnaire/general-health-questionnaire-faqs |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [Internet]. London, England: GL-Assessment; ©2015 [Cited December 16, 2015]. Available from: http://www.gl-assessment.co.uk/products/hospital-anxiety-and-depression-scale-0 |

| HSCL25 | Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, et al. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1-15 |

| K-SADS-PL | Diagnostic Interview Kiddie-SADS-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) [Internet]. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh; ©1996 [Cited December 18, 2015]. Available from: http://www.psychiatry.pitt.edu/sites/default/files/Documents/assessments/ksads-pl.pdf |

| MASC | Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children–2nd Edition [Internet]. Cheektowaga, NY: Multi-Health Systems; ©2015. [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: https://ecom.mhs.com/(S(4uxe4l553naha2zh4z0tjv55))/product.aspx?gr=cli&prod=masc2&id=overview |

| MFQ | The MFQ [Internet]. Durham, NC: Duke University; ©2008 [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: http://devepi.duhs.duke.edu/instruments.html |

| PAT | The Psychosocial Assessment Tool [Internet]. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; ©2015 [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/psychosocial-assessment.aspx |

| PSC | Pediatric Symptom Checklist [Internet]. Boston, MA: Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Psychiatry; ©2015 [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: http://www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/services/psc_about.aspx |

| PTSD RI | UCLA Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index for DSM IV [Internet]. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA; ©2012 [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: http://www.nctsn.org/content/ucla-posttraumatic-stress-disorder-reaction-index-dsm-iv |

| RBPC | Revised Behavior Problem Checklist (RBPC)–PAR Edition [Internet]. Lutz, FL: PAR; ©2012 [Cited December 20, 2015] Available from: http://www4.parinc.com/Products/Product.aspx?ProductID=RBPC |

| RCMAS | RCMAS-2 [Internet]. Cheektowaga, NY: Multi-Health Systems; ©2015 [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: http://www.mhs.com/product.aspx?gr=edu&prod=rcmas2&id=overview |

| SAFA | Franzoni M, Monti M, Pellicciari A, et al. SAFA: a new measure to evaluate psychiatric symptoms detected in a sample of children and adolescents affected by eating disorders. Correlations with risk factors. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:207-214 |

| SCARED | Screen for Childhood Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED) [Internet]. San Diego, CA: The California Evidence Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare; ©2015 [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: http://www.cebc4cw.org/assessment-tool/screen-for-childhood-anxiety-related-emotional-disorders-scared/ |

| SCICA | ASEBA Semistructured Clinical Interview for Children & Adolescents (SCICA 6/18) [Internet]. Lutz, FL: PAR; ©2012 [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: http://www4.parinc.com/Products/Product.aspx?ProductID=SCICA |

| SCL-90-R | Symptom Checklist-90-Revised [Internet]. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Clinical; ©2015. [Cited December 20, 2015]. Available from: http://www.pearsonclinical.com/psychology/products/100000645/symptom-checklist-90-revised-scl-90-r.html# |

| SDQ | SDQ [Internet]. London, England: youthinmind; ©2009 [Cited December 22, 2015]. Available from: http://www.sdqinfo.com/ |

| STAI-C | State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children [Internet]. Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden Inc; ©2002 [Cited December 23, 2015]. Available from: http://www.mindgarden.com/146-state-trait-anxiety-inventory-for-children |

| TMAS | Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale [Internet]. Reading, MA: Psychology Tools; ©2015 [Cited December 23, 2015]. Available from: https://psychology-tools.com/taylor-manifest-anxiety-scale/ |

| VPHQ | Karling M, Hägglöf B. Child behaviour after anaesthesia: association of socioeconomic factors and child behaviour checklist to the Post-Hospital Behaviour Questionnaire. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(3):418-423 |

| YAAS | Bruzzese J, Unikel L, Shrout PE, et al. Youth and Parent Versions of the Asthma-Related Anxiety Scale: development and initial testing. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2011;24(2):95-105 |

| YSR | Youth Self-Report 11-18 [Internet]. Los Angeles, CA: The National Center for Child Traumatic Stress; ©2012 [Cited December 28, 2015]. Available from: http://www.nctsn.org/content/youth-self-report-11-18 |

Newer version available.

Depression

Twenty-eight instruments for identifying depression in children and adolescents with LTPCs were found by our search (Table 1). These included the BASC-2,32 BDI-II,33 BDI-FS,34 BSI 18,35 BYI-II,36 CBCL,37 CCSRC-R1,38 CDI,39 CDRS-R,40 CESD,41 CPMS,42 DAWBA,43 DICA,44 DISC-IV,45 DI,46 GHQ-28,47 HADS,48 HSCL 25,49 K-SADS-PL,50 MFQ,51 PAT,52 PSC,53 SAFA,54 SCICA,55 SCL-90-R,56 SDQ,57 VPHQ,58 and YSR.59 Of these, the only instruments to have been psychometrically investigated by Canning10 in a single sample of 112 children and adolescents with multiple LTPCs, aged 9 to 18 years from a tertiary care medical center in the United States, were the CBCL, CDI, and PSC, all of which were compared with the DISC-IV intensive structured clinical interview as a gold standard. In this study, all 3 instruments demonstrated low sensitivity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value, but high specificity.

Anxiety

Twenty-eight instruments for identifying anxiety in children and adolescents with LTPCs were identified by our search (Table 1). These included the BAI,60 BASC-2,32 BYI-II,36 CBCL,37 CPMS,42 DAWBA,43 DICA,44 DISC-IV,45 DI,46 GHQ-28,47 HADS,48 K-SADS-PL,50 MASC,61 PAT,52 PSC,53 PTSD RI,62 RCMAS,63 SAFA,54 SCARED,64 SCICA,55 SCL-90-R,56 SDQ,57 STAI-C,65 TMAS,66 VPHQ,58 YAAS,67 and YSR.59 None of these instruments had been validated as a screening tool for anxiety in the target population, either against a gold standard or other instrument. Nor had any sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, or negative predictive values been reported by any of the authors of these studies.

Behavior Problems

Eighteen instruments for identifying behavior problems in children and adolescents with LTPCs were found by our search (Table 1). These included the BASC-2,32 BYI-II,36 CBCL,37 CBQ,68 Conners,69 CPMS,42 DAWBA,43 DICA,44 DISC-IV,45 DI,46 GHQ-28,47 K-SADS-PL,50 PSC,53 RBPC,70 SCICA,55 SDQ,57 VPHQ,58 and YSR.59 Of these, the CBCL, SDQ, and YSR were the most commonly used, and only the CBCL had specifically been validated with this population.10

Substance Use Problems

Only 2 instruments for identifying substance use problems in children and adolescents with LTPCs were found by our search, namely, the DICA44 and DISC-IV45 (Table 1). Neither of these instruments was purpose-designed as an instrument for rating substance use problems and both identified these issues as part of a broader DSM-IV71 aligned assessment process in research settings. Neither instrument had been validated as a screening tool for substance use problems in the target population, either against a gold standard or other instrument, and no sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, or negative predictive values have been reported by any of the authors of these studies.

Family Problems

Seven instruments for assessing family problems were identified by our search, namely, the DICA,44 FACES III,72 FAD,73 FES,74 FFFS,75 PAT,52 and SDQ57 (Table 1). None of these instruments had been validated as a screening tool for family problems in the target population, either against a gold standard or other instrument. Nor had any sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive values, or negative predictive values been reported by any of the authors of these studies.

Multiple Problems

Of the instruments we found, the DICA44 was the only one that identified all 5 types of problem, namely, depression, anxiety, behavior, substance use problems, and family issues. The DISC,45 GHQ-28,47 and SDQ57 being broad screening instruments identified 4 of these problems (the first two excluding family issues, the third excluding substance use problems). The combination of depression, anxiety, and behavior problems was identified by the BASC-2,32 BYI-II,36 CBCL,37 CPMS,42 DAWBA,43 DI,46 K-SADS-PL,50 SCICA,55 VHPQ,58 and YSR.59 The combination of depression, anxiety, and family problems was identified by the PAT.52 Overall, none of our identified instruments proved to be a clinically viable instrument for easily identifying all of these problem areas in children and adolescents with LTPCs.

Discussion

Children and adolescents with LTPCs remain at greater risk of developing psychosocial problems. Despite enthusiasm from public health and funding bodies to routinely identify and address common childhood mental health problems as early as possible in high-risk groups,76-79 there is inadequate evidence to recommend doing so using currently available psychometric instruments.80,81 Targeted screening using some of these tools is probably more valid. Of the 44 potential instruments evaluated by us, none met the criteria for an “ideal screening instrument” outlined prior to the commencement of the review and most had only had confirmation of their psychometric properties within the general population.

Previous reviewers of psychometric instruments for children and adolescents have had varying views, as outlined below, partly due to differences in focus and partly due to when their reviews were undertaken. Myers,27,82 Brookes,28 Stocking,83 and Quittner84 have conducted the most comprehensive reviews of instruments for identifying depression and anxiety. Myers82 recommended the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS85) and Reynolds Child Depression Scale (RCDS86) for the identification of depression in the general population, and a combination of the clinician-rated CDRS-R40 and patient-rated CDI-287 for identifying depression in clinical populations, the latter instruments being more sensitive to clinical change. Both Brookes28 and Stocking83 identified significant limitations in the KSADS,50 DISC,45 DICA,44 BDI,33 Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS88), and Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS89) for identifying depressive symptoms, and the BDI-II,33 CDI-2,87 CES-D,41 and RADS85 in identifying “caseness.” A recent consensus statement on the identification of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis88 recommended that the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-990) should be routinely used to screen children with the condition over the age of 12 years as it is brief, reliable, has valid optimal cutoff scores for detecting psychological symptoms that map onto DSM-591 criteria, and is free and available in all major languages. Unfortunately, no studies of children and adolescents with LTPCs using the PHQ-9 were identified by our search, leaving us unable to comment on this recommendation. The BDI-FS34 was designed for “evaluating symptoms of depression in patients reporting somatic and behavioral symptoms that may be attributable to biological, medical, alcohol, and/or substance abuse” and has been shown to be better than the PHQ-9 at discriminating between depressive and somatic symptoms.92 Although most studies have focused on its use in primary care and only one study in children with LTPCs was identified by us, it shows some promise.

Myers and Brookes favored the MASC and SCARED for identifying anxiety, due to their clear constructs, adequate internal psychometric properties, ability to discriminate between anxiety and depression, response formats that should detect treatment effect, short screening forms, and parallel parent-report forms. Myers and Brookes disagreed on the value of the RCMAS63 and STAI C,65 with the latter favoring these instruments. Brooks and Kutcher additionally identified the CBCL,37 K-SADS-PL,50 and ADIS-C/P93 as viable instruments for detecting anxiety. Quittner recommended the GAD-794 for identifying anxiety in children over the age of 12 years with cystic fibrosis.

Comprehensive reviews of instruments for identifying behavior disorders in children and adolescents95,96 have previously recommended the Conners,69 Swanson Nolan and Pelham IV Questionnaire (SNAP-IV),97 Attention Deficit Disorder Evaluation Scale (ADDES-298), and ADHD Symptom Rating Scale (ADHD-SRS99) for identifying combined/hyperactive symptoms of ADHD; the Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scale (BADDS100) for identifying inattention; the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI101), the Sutter-Eyberg Student Behavior Inventory–Revised (SESBI-R102), and the New York Teacher Rating Scale for Disruptive and Antisocial Behavior (NYTRS103) for assessing broad constructs of disruptive behavior disorder; and the Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD104) for evaluating youth with conduct disorder.

A number of well-validated, specific, and brief instruments exist for identifying substance use problems in young people including the CRAFFT105 substance abuse screening test, recommended by Pilowsky106 following a recent review of screening instruments for adolescent substance abuse in primary care settings; the Personal Experience Short Questionnaire (PESQ107), recommended by Farrow108 during a similar review for the Washington State Division of Alcohol and Substance Abuse; and newer instruments such as the Substances and Choices Scale (SACS109) and the Teen Addiction Severity Index (T-ASI110). Despite their lack of use and psychometric validation with children and adolescents with LTPCs, their specific design for identifying substance use problems, cost, and ease of use probably make them better choices for the targeted identification of such problems in clinical settings compared with the DICA44 or DISC-IV.45

The FACES III,72 FAD,73 FES,74 and FFFS75 were exclusively designed to assess family functioning, and despite lack of psychometric validation in children and adolescents with LTPCs, they had all been shown to be of some clinical use in this population. Out of all the identified instruments, the PAT 2.052,111,112 is the most extensively researched and promising screening instrument for systemic issues within families of children and adolescents with LTPCs. It is linked to a triaging system, based on the Pediatric Psychology Preventative Health (PPPH) model113 to ensure appropriate referrals are made, and information provided to the treating team. It has been researched in families of children with conditions such as cancer,52 congenital heart disease,114 inflammatory bowel disease,115 and kidney transplants.116 While it has shown good discrimination in terms of family and parental psychosocial difficulties and behavior problems, it has not specifically been researched as a screener for childhood or adolescent anxiety or depression.

This review provides a snapshot of instruments that have been used in children and adolescents with LTPCs and some information regarding their nature. There are a number of other considerations to be factored in when deciding which screening instruments to use for identifying psychosocial problems in this population, when to use such instruments, and how to do so. All scales are not built equal. Briefer scales such as the MFQ designed for quick identification of conditions are less comprehensive, but more practical to use in clinical settings than comprehensive assessment questionnaires such as the DISC-IV.117 Although clinician-rated scales have been shown to be more accurately predict outcomes than self-report scales, the former are more commonly used, are more relevant to patient-centered care,118 and the 2 scales are best used in combination for optimum result. Newer scales are more accurate than older scales, particularly in discriminating between overlapping constructs such as anxiety and depression.29 However, the former have a longer track record and clinicians may be more familiar with them. If identification of “cases” rather than symptoms is important, checklists that are aligned with diagnostic manuals such as the DSM-571 are probably more useful than those that rate symptoms continuously using different paradigms. Online or electronically available scales allow for efficient data analysis, but can be costly and off-putting for those with less familiarity with technology. Finally, acceptability and validity of scales in different languages and cultures is important to establish as some instruments such as the GAD7 have been shown to be less accurate in some groups (eg African Americans) than others.119

Limitations of this review include the fact that only instruments used in studies of children and adolescents with LTPCs were included in the main analysis and other newer and potentially useful scales that have been not similarly researched may have been excluded. In addition, few instruments had psychometric data pertaining to the target population and assumptions of efficacy had to be made for most instruments based on their properties within the general population. Strengths of the review include the wide range of LTPCs with which identified instruments had been used and the correlation of our findings with those of key reviews of these instruments in the wider population to enable recommendations for clinicians and researchers that are based on the most up-to-date evidence.

Overall, in our opinion, the best instruments identified by us for targeted screening for psychosocial problems in children and adolescents with LTPCs are as follows. For depression, the clinician-rated CDRS-R40 and patient-rated CDI-2,87 BDI,32 and PHQ-990 are the easiest to use and best regarded instruments, with the BDI-FS34 showing promise. For anxiety, the self/parent-rated MASC-2,61 SCARED,64 and GAD-794 all have satisfactory appeal. Behavior problems are best identified using the parent-rated SDQ57 and CBCL,37 and ADHD is best identified using the self/parent/teacher-rated Conners-3.69 Substance use problems are best screened for using the well-established self-rated CRAFFT105 and PESQ107 or newer but easier to use scales such as the SACS109 and T-ASI.110 Family problems are best identified using the parent-rated PAT 2.0,52 and finally, depending on their combination, multiple problems may be screened for using a limited range of instruments including the parent-rated BASC-3,32 SDQ,57 and PAT 2.0.52

Just as important as screening is what comes after it. Care pathways and provision of high-quality care should be in place before the implementation of any targeted or universal screening programme.120 Future research should include more in-depth evaluation of existing instruments in children and adolescents with LTPCs and the development of more specific instruments for identifying psychosocial problems in this population.

Conclusions

For now, clinicians should continue to be vigilant regarding the greater likelihood of psychosocial problems in children and adolescents with LTPCs and should only use recommended instruments in a targeted manner to support clinical judgment within an established continuum of care.

Author Contributions

HT: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript; gave final approval; agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

HM: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript.

KG: Contributed to analysis and interpretation; drafted the manuscript; critically revised the manuscript.

KM: Contributed to conception and design; contributed to acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafted the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anne Wilson for her assistance with data extraction and the Starship Foundation New Zealand for supporting some of KG’s time on this project (Grant number SF985).

Appendix

Keywords Used for Ovid Medline Database Search on December 30, 2014

Mass Screening/

screen$.tw.

identif$.tw.

detect$.tw.

(routine$ adj3 (ask$ or question$)).tw.

assess*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier]

risk.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier]

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7

psychological problem*.tw.

exp stress, psychological/

((emotion* or psycholog* or mental or mental health) adj3 (stress* or problem* or disturb* or aspect* or state* or ill*)).tw.

child psychology/

adolescent psychology/

psychosocial.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier]

9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14

ANXIETY DISORDERS/ or AGORAPHOBIA/ or NEUROCIRCULATORY ASTHENIA/ or OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE DISORDER/ or PANIC DISORDER/ or PHOBIC DISORDERS/ or STRESS DISORDERS, TRAUMATIC/ or STRESS DISORDERS, POST-TRAUMATIC/ or anxiety, separation/ or neurotic disorders/

(anxi* or generali* anxiety disorder* or GAD or obsessive compulsive or OCD or phobi* or obsess* or compulsi* or panic or phobi* or ptsd or posttrauma* or post trauma* or social phobia or panic attack* or neurotic or neurosis).tw.

((procedur* or treat* or manage*) adj3 anxiety).tw.

((hospi* or clinic*) adj3 anxiety).tw.

16 or 17 or 18 or 19

MOOD DISORDERS/ or AFFECTIVE DISORDERS, PSYCHOTIC/ or BIPOLAR DISORDER/ or CYCLOTHYMIC DISORDER/ or DEPRESSIVE DISORDER/ or DEPRESSION, POSTPARTUM/ or DEPRESSIVE DISORDER, MAJOR/ or DEPRESSIVE DISORDER, TREATMENT-RESISTANT/ or DYSTHYMIC DISORDER/ or SEASONAL AFFECTIVE DISORDER/ or AFFECTIVE SYMPTOMS.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier]

(mood disorder* or affective disorder* or bipolar i or bipolar ii or (bipolar and (affective or disorder*)) or mania or manic or cyclothymic* or depression or depressive or depressed or dysthymi* or anhedoni* or affective symptoms).tw.

21 or 22

15 or 20 or 23

infant*.tw.

child*.tw.

adolesc*.tw.

(baby or babies or newborn* or new-born* or neonat* or neo-nat* or toddler* or preschool* or pre-school* or schoolchild* or school-child* or boy* or girl* or teen* or preteen* or pre-teen* or youth* or young* person* or young people* or pediatr* or paediatr* or juveni* or minors).tw.

25 or 26 or 27 or 28

exp pain/

exp complex regional pain syndromes/

exp rheumatic diseases/

exp neoplasms/

exp diabetes mellitus/

exp asthma/

exp brain injuries/

exp brain damage, chronic/

exp inflammatory bowel diseases/

exp anemia, sickle cell/

exp skin diseases/

Chronic Disease/

Cystic Fibrosis/

Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia/

respiratory tract disease/ or exp bronchiectasis/

Kidney Failure, Chronic/

heart diseases/ or exp heart defects, congenital/

exp liver diseases/

((chronic* or longterm* or long-term*) adj5 (condition* or ill* or disease*)).tw.

(kidney* or renal or cystic or heart or cardiac or colon or lung or lungs or asthma* or diabet* or rheumat* or arthrit* or fibromyalg* or cancer* or neoplas* or tumor* or tumour* or malignan* or carcinoma* or respirat* or bronchi* or epilep* or eczema or dermati* or leuk* or liver).tw.

((brain or head) adj5 (trauma* or injur*)).tw.

(bowel* adj5 (condition* or disease* or illness* or inflam*)).tw.

brain diseases/ or brain abscess/ or brain diseases, metabolic/ or brain neoplasms/ or cerebrovascular disorders/ or encephalitis/ or epilepsy/ or hydrocephalus/ or hypoxia, brain/

30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52

8 and 24 and 29 and 53

limit 54 to (english language and yr = “1994 -Current”)

randomized controlled trial/

controlled clinical trial.pt.

randomi#ed.ab.

placebo*.ab.

randomly.ab.

trial.ab.

clinical trials as topic.sh.

groups.ab.

56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63

exp animals/ not humans.sh.

64 not 65

55 and 66

Psychological Distress.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier]

8 and 29 and 53 and 68

limit 69 to (english language and yr = “1994 -Current”)

70 and 66

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Part of this study was funded by the Starship Foundation New Zealand, Grant SF985.

References

- 1. Eiser C. Effects of chronic illness on children and their families. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 1997;3:204-210. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenbaum P. Prevention of psychosocial problems in children with chronic illness. CMAJ. 1998;139:293-295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiland SK, Pless IB, Roghmann KJ. Chronic illness and mental health problems in pediatric practice: results from a survey of primary care providers. Pediatrics. 1992;89:445-449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Newacheck PW, McManus MA, Fox HB. Prevalence and impact of chronic Illness among adolescents. Am J Dis Childhood. 1991;145:1367-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gortmaker SL, Walker DK, Weitzman M. Chronic conditions, socioeconomic risks and behavioral problems in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1990;85:267-276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cadman D, Boyle M, Szatmari P, Offord DR. Chronic illness, disability and mental and social wellbeing; finding of the Ontario child health study. Pediatrics. 1987;79:805-813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pless IB, Roghmann KJ. Chronic illness and its consequences: observations based on three epidemiologic surveys. J Pediatr. 1971;79:351-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Boscarino JA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and physical illness: results from clinical and epidemiologic studies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:141-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Price J, Kassam-Adams N, Alderfer MA, Christofferson J, Kazak A. Systematic review: a reevaluation and update of the Integrative (Trajectory) Model of Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2016;41:86-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Canning EH, Kelleher K. Performance of screening tools for mental health problems in chronically ill children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:272-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kutner L, Olson CH, Schlozman S, Goldstein M, Warner D, Beresin EV. Training pediatric residents and pediatricians about adolescent mental health problems: a proof of concept pilot for a proposed national curriculum. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32:429-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. La Greca AM, Follansbee D, Skyler JS. Developmental and behavioral aspects of diabetes management in youngsters. Child Health Care. 1990;19:132-139. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Delamater AM, Kurtz SM, Bubb J, White NH, Santiago IV. Stress and coping in relation to metabolic control in adolescents with type-1 diabetes. Dev Behav Pediatr. 1987;8:136-140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phipps S, Klosky JL, Long A, et al. Posttraumatic stress and psychological growth in children with cancer: has the traumatic impact of cancer been overestimated? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:641-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yallop K, McDowell H, Koziol-McLain, Reed PW. Self-reported psychosocial wellbeing of adolescent childhood cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17:711-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sawyer MG, Antoniou G, Toogood I, Rice M. Childhood cancer: a two year prospective study of the psychological adjustment of children and parents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1736-1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Breslau N, Staruch KS, Mortimaer EA. Psychological distress in mothers of disabled children. Arch J Dis Child. 1982;136:682-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Engstrom I. Parental distress and social interaction in families with children with inflammatory bowel disease. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991;30:904-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Walker LS, Ford MB, Donald WD. Cystic fibrosis and family stress: effects of age and severity of illness. Pediatrics. 1987;79:239-246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mulhern RK, Fairclough DL, Smith B, Douglas SM. Maternal depression, assessment methods and physical symptoms affect estimates of depressive symptomatology among children with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 1992;17:313-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cavanaugh SV, Clark DC, Gibbons RD. Diagnosing depression in the hospitalized medically ill. Psychosomatics. 1983;24:809-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Clark DC, Cavanaugh SV, Gibbons RD. The core symptoms of depression in medical and psychiatric patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1983;171:705-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ritter EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depression in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:66-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Quittner AJ, Abbott J, Georgiopoulos AM, et al. International Committee on Mental Health in Cystic Fibrosis: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and European Cystic Fibrosis Society consensus statements for screening and treating depression and anxiety. Thorax. 2016;71:26-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wilson JM, Jungner G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease (World Health Organization Public Health Paper No. 34). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goldenring J, Rosen D. Getting into adolescent heads: an essential update. Contemp Pediatr. 2004;21:64. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Myers K, Winters NC. Ten-year review of rating scales. I: overview of scale functioning, psychometric properties, and selection. J Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:114-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Brooks SJ, Kutcher S. Diagnosis and measurement of anxiety disorders in adolescents: a review of commonly used instruments. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. 2003;13:351-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Streiner DL. A checklist for evaluating the usefulness of rating scales. Can J Psychiatry. 1993;38:140-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cohen J. A coefficient for agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37-46. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, Altman DG. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med. 2010;7(2):e1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reynolds C. Behavior Assessment System for Children. New York, NY: John Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory–II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-FastScreen for Medical Patients: Manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Derogatis LR. BSI 18, Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. New York, NY: NCS Pearson; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beck JS. Beck Youth Inventories. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation/Harcourt Brace; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ayers TS, Sandler IN. Manual for the children’s coping strategies checklist & the How I Coped Under Pressure Scale. http://prc.asu.edu/docs/CCSC-HICUPS%20%20Manual2.pdf. Published 1999. Accessed January 17, 2017.

- 39. Kovacs M. The Children’s Depression Inventory: A Self-Rating Depression Scale for School-Aged Youngsters (Unpublished manuscript). Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Poznanski EO, Cook SC, Carroll BJ. A depression rating scale for children. Pediatrics. 1979;64:442-450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385-401. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Malhotra S, Varma VK, Verma SK, Malhotra A. Childhood Psychopathology Measurement Schedule: development and standardization. Indian J Psychiatry. 1988;30:325-331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, Gatward R, Meltzer H. The Development and Well-Being Assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:645-655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Herjanic B, Reich W. Diagnostic Interview for Children and Adolescents (DICA). St Louis, WA: Department of Psychiatry, Washington University School of Medicine; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Valla JP, Bergeron L, Bérubé H, Gaudet N, St-Georges M. A structured pictorial questionnaire to assess DSM-III-R-based diagnoses in children (6-11 years): development, validity, and reliability. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1994;22:403-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Goldberg DP. The Detection of Psychiatric Illness by Questionnaire: A Technique for the Identification and Assessment of Non-Psychotic Psychiatric Illness. London, England: Oxford University Press, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatry Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19:1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Ryan N. Kiddie-SADS-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL). Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh, School of Medicine; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Angold A, Costello EJ. Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ). Durham, NC: Developmental Epidemiology Program, Duke University; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kazak AE, Prusak A, McSherry M, et al. The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT): pilot data on a brief screening instrument for identifying high risk families in pediatric oncology. Fam Syst Health. 2001;19:303-317. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jellinek MS, Murphy JM, Robinson J, Feins A, Lamb S, Fenton T. Pediatric Symptom Checklist: screening school-age children for psychosocial dysfunction. J Pediatr. 1988;112:201-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cianchetti C, Sannio Fascello G. Scale psichiatriche di autosomministrazione per fanciulli e adolescenti (SAFA). Firenze, Italy: Organizzazioni Speciali; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH. Child Behavior Checklist: Semistructured Clinical Interview for Children and Adolescents (SCICA). Burlington, VT: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Derogatis LR. SCL-90-R: Administration, Scoring of Procedures Manual-II for the Revised Version and Other Instruments of the Psychopathology Rating Scale Series. Towson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38:581-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vernon DT, Schulman JL, Foley JM. Changes in children’s behavior after hospitalization: some dimensions of response and their correlates. Am J Dis Child. 1966;111:581-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56:893-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1997;36:554-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:96-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, et al. The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): scale construction and psychometric characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:545-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Spielberger CD, Edwards CD. STAIC Preliminary Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children (“How I Feel Questionnaire”). Sunnyvale, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Taylor JA. Manifest Anxiety Scale. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Bruzzese JM, Unikel LH, Shrout PE, Klein RG. Youth and parent versions of the Asthma-Related Anxiety Scale: development and initial testing. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2011;24:95-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Rothbart MK, Ahadi SA, Hershey KL, Fisher P. Investigations of temperament at three to seven years: the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire. Child Dev. 2001;72:1394-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Conners CK. Conners’ Rating Scales–Revised: User’s Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Quay HC, Peterson DR. Manual for the Revised Behavior Problem Checklist. Miami, FL: Department of Psychology, University of Miami; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 71. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 72. Olson DH, Portner J, Lavee Y. Faces III Manual. St Paul, MN: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9:171-180. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Moos RH. Evaluating Correctional and Community Settings. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Roberts CS, Feetham SL. Assessing family functioning across three areas of relationships. Nurs Res. 1982;31:231-235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Semansky R, Koyanagi C, Vandivort-Warren R. Behavioral health screening policies in Medicaid programs nationwide. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:736-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health and Task Force on Mental Health Policy statement—the future of pediatrics: mental health competencies for pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2009;124:410-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. US Preventative Task Force. Screening and treatment for major depressive disorder in children and adolescents. US Preventative Task Force recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1223-1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. The NICE Guideline on the Management of Management and Treatment of Depression in Adults. Updated edition Leicester, England: British Psychological Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Northern California Training Agency. Mental Health Screening and Assessment Tools for Children: Literature Review. Davis, CA: Northern California Training Agency; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ozonoff S. Early detection of mental health and neurodevelopmental disorders: the ethical challenges of a field in its infancy. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2015;56:933-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Myers K, Winters NC. Ten-year review of rating scales. II: scales for internalizing disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:634-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Stocking E, Degenhardt L, Lee YY, et al. Symptom screening scales for detecting major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of reliability, validity and diagnostic utility. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:447-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Quittner AJ, Goldbeck L, Abbott J, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with cystic fibrosis and parent caregivers: results of the International Depression Epidemiological Study across nine countries. Thorax. 2014;69:1090-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Reynolds WM. Professional Manual for the Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Reynolds WM, Graves A. Reliability of Children’s Reports of Depressive Symptomatology. J Abnorm Child Psychology. 1989;17:647-655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kovac M. Children’s Depression Inventory 2 (CDI 2). North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Montgomery SA, Asberg MA. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509-515. [Google Scholar]

- 91. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Kliem S, Mößle T, Zenger M, Brähler E. Reliability and validity of the Beck Depression Inventory–Fast Screen for medical patients in the general German population. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:236-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Silverman WK, Albano AM. The Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for Children (ADIS-C/P). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 94. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Collett BR, Ohan JL, Myers KM. Ten-year review of rating scales. V: scales assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1015-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Collett BR, Ohan JL, Myers KN. Ten-year review of rating scales. VI: scales assessing externalizing behaviors. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:1143-1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Swanson JM. SNAP-IV Scale. Irvine, CA: University of California Child Development Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 98. McCarney SB. The Attention Deficit Disorders Evaluation Scale, Home Version: Technical Manual. 2nd ed. Columbia, MO: Hawthorne Educational Service; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Holland ML, Gimpel GA, Merrell KW. ADHD Symptoms Rating Scale Manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 100. Brown TE. Brown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scales for Children and Adolescents. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 101. Eyberg S, Boggs SR, Reynolds LA. Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory. Portland, OR: University of Oregon Health Sciences Center; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 102. Funderburk BW, Eyberg SM. Psychometric characteristics of the Sutter Eyeberg Student Behavior Inventory—a school behavior rating scale for use with preschool children. Behav Assess. 1989;11:297-313. [Google Scholar]

- 103. Miller LS, Klein RG, Piacentini J, et al. The New York Teacher Rating Scale for Disruptive and Antisocial Behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:359-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Frick PJ, Hare RD. Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD) Technical Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 105. Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:591-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Pilowksy DJ, Wu LT. Screening instruments for substance use and brief interventions targeting adolescents in primary care: a literature review. Addict Behav. 2013;38:2146-2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Winters KC. Personal Experience Screening Questionnaire (PESQ). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 108. Farrow JA, Smith WR, Hurst MD. Adolescent Drug and Alcohol Assessment Instruments in Current Use. Seattle, WA: Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Christie G, Marsh R, Sheridan J, et al. The Substances and Choices Scale (SACS): the development and testing of a new alcohol and other drug screening and outcome measurement instrument for young people. Addiction. 2007;102:1390-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]