Abstract

Objective

Optimal patient selection for lower extremity revascularization remains a clinical challenge among the hemodialysis-dependent (HD). The purpose of this study was to examine contemporary real world open and endovascular outcomes of HD patients to better facilitate patient selection for intervention.

Methods

A regional multicenter registry was queried between 2003 and 2013 for HD patients (N = 689) undergoing open surgical bypass (n = 295) or endovascular intervention (n = 394) for lower extremity revascularization. Patient demographics and comorbidities were recorded. The primary outcome was overall survival. Secondary outcomes included graft patency, freedom from major adverse limb events, and amputation-free survival (AFS). Multivariate analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors for death and amputation.

Results

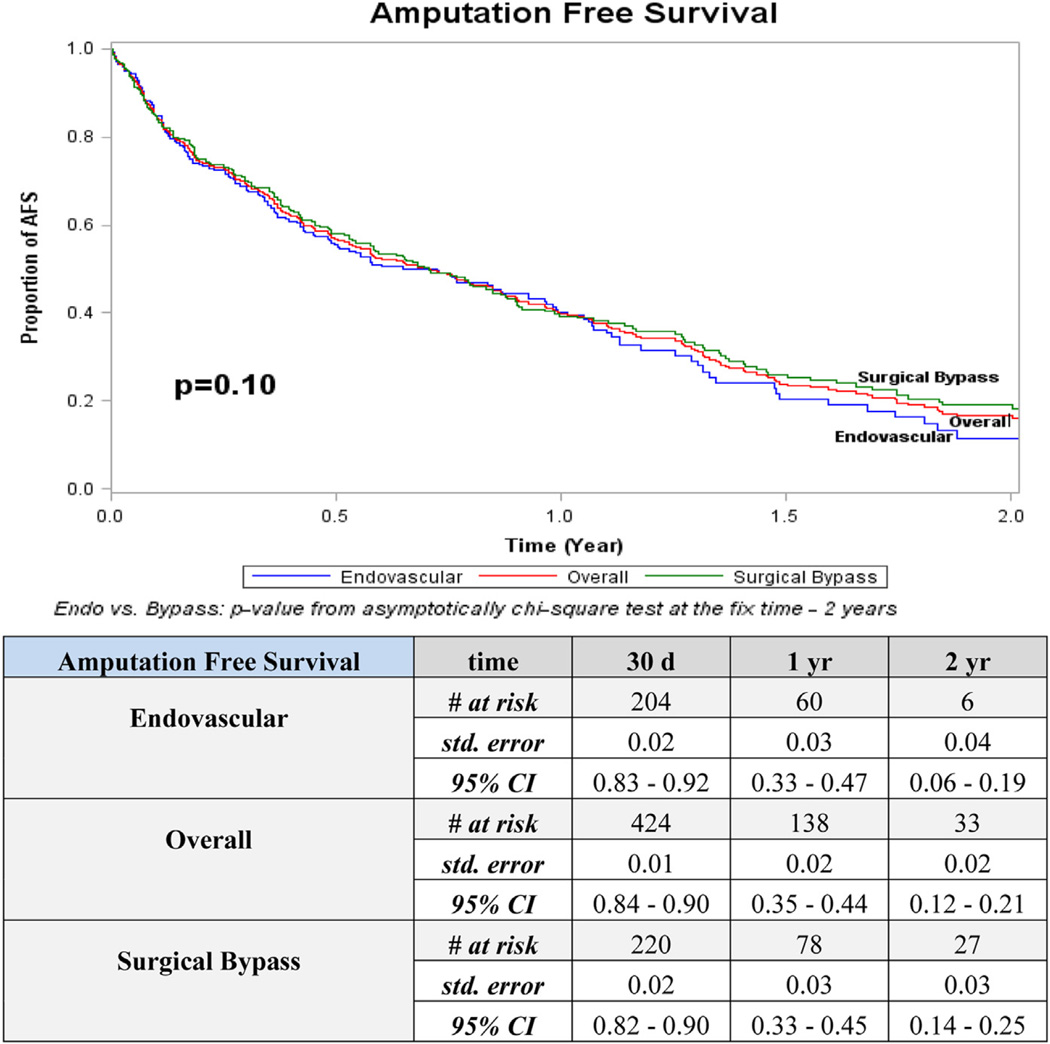

Among the 689 HD patients undergoing lower extremity revascularization, 66% were male, and 83% were white. Ninety percent of revascularizations were performed for critical limb ischemia and 8% for claudication. Overall survival at 1, 2, and 5 years survival remained low at 60%, 43%, and 21%, respectively. Overall 1- and 2-year AFS was 40% and 17%. Mortality accounted for the primary mode of failure for both open bypass (78%) and endovascular interventions (80%) at two years. Survival, AFS, and freedom from major adverse limb event outcomes did not differ significantly between revascularization techniques. At 2 years, endovascular patency was higher than open bypass (76% vs 26%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28–0.71; P = .02). Multivariate analysis identified age ≥80 years (hazard ratio [HR], 1.9; 95% CI, 1.4–2.5; P < .01), indication of rest pain or tissue loss (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3–2.6; P < .01), preoperative wheelchair/bedridden status (HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1<2.1; P < .01), coronary artery disease (HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2<1.9; P < .01), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1<1.8; P = .01) as independent predictors of death. The presence of three or more risk factors resulted in predicted 1-year mortality of 64%.

Conclusions

Overall survival and AFS among HD patients remains poor, irrespective of revascularization strategy. Mortality remains the primary driver for these findings and justifies a prudent approach to patient selection. Focus for improved results should emphasize predictors of survival to better identify those most likely to benefit from revascularization.

Overall survival among hemodialysis-dependent (HD) patients undergoing lower extremity (LE) revascularization remains the crux for surgical decision making in this challenging patient population. Despite advances in surgical techniques, there has been little improvement in outcomes among these patients. In fact, 2-year overall survival rates following LE bypass in this population remain 23% to 52%.1–6 With less than 25% of HD patients with a foot lesion alive at 5 years, the prognosis of a HD patient with peripheral artery disease (PAD) remains worse than most cancers.7 Furthermore, PAD is a common and growing problem in HD patients. PAD has been shown to affect nearly one-third of patients on HD,8 and, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, end-stage renal disease (ESRD) has increased by 600% over the past three decades. The advent and evolution of catheter-based therapies, however, may offer a less morbid therapeutic alternative for limb salvage in this patient population, though contemporary outcomes remain limited.

With an increasingly prevalent population of highly morbid HD patients with PAD, it is necessary to discern methods to optimize the delivery of LE revascularization. Interestingly, studies that demonstrated dismal survival reported satisfactory graft patency and limb salvage rates (60%–74% and 50%–85% at 2 years, respectively).1–6 The contrast between poor survival and acceptable patency implies that many patients die from causes unrelated to their affected extremity. Thus, further work should focus on identifying HD patients with increased survival potential that can derive benefit from undergoing revascularization.

Therefore, the goal of this project was to conduct a contemporary, multicenter analysis of HD patients undergoing lower extremity revascularization. We queried patients within the Vascular Study Group of New England (VSGNE) to better understand relationships between revascularization, ESRD, and patient- and limb-related outcomes.

METHODS

Subjects and database

Data was collected using the VSGNE regional quality improvement registry. Included subjects were HD who underwent LE revascularization at or distal to the common iliac artery (n = 689) over the study interval (2003–2013). The overall group was stratified by revascularization technique: open surgical bypass (n = 295) and endovascular revascularization (n = 394). Patient demographics, comorbidities, and surgical characteristics were recorded. Indications for revascularization primarily included critical limb ischemia (rest pain, tissue loss, acute limb threatening ischemia) and a small subset of patients (<10%) with claudication. Aortic procedures were excluded.

Definitions

All included procedures were identified as the first revascularization noted for each patient. Although some patients ultimately underwent either open or catheter-based reintervention during the study period, clinical outcomes were associated with the index procedure.

Outcome measures

Patient demographics and surgical characteristics of the cohort were analyzed and stratified by revascularization technique. Analysis of short- and long-term outcomes were similarly examined by overall, surgical, and endovascular techniques. Follow-up reporting was done at 30 days, and 1, 2, and 5 years. The main outcome measure was overall survival. Secondary outcomes examined were patency, freedom from major adverse limb event (MALE), and amputation-free survival (AFS). Patency was confirmed at discharge and follow-up by clinical exam and duplex study and considered either patent (primary, primary-assisted, or secondary) or occluded. MALE included any ipsilateral amputation or vascular reintervention (surgical or endovascular) on the initial side of revascularization. AFS required the absence of either amputation or death. Deaths were censored to examine impact of failure modes on AFS and amputation-free rates were calculated.

Statistical methods

Patient demographics and procedure characteristics were compared between groups using χ2 test for categorical variables. Time-to-event end-points at the fixed time point were estimated using Kaplan-Meier analysis and contrasted using asymptotical χ2 test. Log-rank test was also applied to compare overall survival functions stratified by number of risk factors. Cox proportional hazard model was performed to identify risk factors and calculate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals. All tests were considered statistically significant at 0.05. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects verified that our study did not utilize identifiable private patient information and therefore was exempt from Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects review.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

The majority of patients were male (66%; n = 455), in their sixth decade (31%; n = 210), and Caucasian (83%; n = 575). Typical vascular risk factors and comorbidities were present, with a notable 80% prevalence of concomitant diabetes (Table I). Increased rates of prior smoking (55% vs 51%; P = .05), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD; 30% vs 22%; P = .01), and hypertension (97% vs 94%; P = .05) were seen in the open compared with the endovascular group.

Table I.

Patient and procedural characteristics

| Patient demographics | Overall (N = 689) |

Surgical open bypass (n = 295) |

Endovascular (n = 394) 686 segments |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| <60 | 182 (26) | 74 (25) | 108 (27) | .35 |

| 60–69 | 210 (31) | 84 (29) | 126 (32) | |

| 70–79 | 191 (28) | 92 (31) | 99 (25) | |

| >80 | 106 (15) | 45 (15) | 61 (16) | |

| Male gender | 455 (66) | 194 (66) | 261 (66) | .90 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Never | 194 (28) | 69 (23) | 125 (32) | .05 |

| Past | 362 (53) | 162 (55) | 200 (51) | |

| Current | 132 (19) | 63 (21) | 69 (18) | |

| CAD | 342 (50) | 158 (54) | 184 (47) | .08 |

| COPD | 174 (25) | 89 (30) | 85 (22) | .01 |

| CHF | 296 (43) | 130 (44) | 166 (42) | .63 |

| HTN | 655 (95) | 286 (97) | 369 (94) | .05 |

| DM | ||||

| None | 135 (20) | 60 (20) | 75 (19) | .67 |

| Any diabetes | 554 (80) | 235 (80) | 319 (81) | |

| Ambulatory status | ||||

| Amb | 379 (55) | 159 (54) | 220 (56) | .16 |

| Amb w/ assistance | 207 (30) | 100 (34) | 107 (27) | |

| Wheelchair | 84 (12) | 31 (11) | 53 (14) | |

| Bedridden | 17 (3) | 5 (2) | 12 (3) | |

| Living | ||||

| Home | 618 (90) | 271 (92) | 347 (88) | .10 |

| Nursing home/homeless | 71 (10) | 24 (8) | 47 (12) | |

| Indication | ||||

| CLI (rest pain/tissue loss/acute ischemia) | 617 (90) | 276 (95) | 341 (90) | .027 |

| Claudication | 52 (8) | 15 (5) | 37 (10) | |

| Procedure characteristics | ||||

| Urgency | ||||

| Elective | 448 (65) | 200 (68) | 248 (63) | .41 |

| Urgent | 230 (33) | 91 (31) | 139 (35) | |

| Emergent | 11 (1) | 4 (1) | 7 (2) | |

| At-or below-knee target | 617 (63) | 242 (82) | 375 (55) | <.01 |

| Above-knee target | 363 (37) | 52 (18) | 311 (45) | <.01 |

Amb, Ambulatory; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, congestive heart failure; CLI, critical limb ischemia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

Data are presented as number (%).

Critical limb ischemia (rest pain, tissue loss, acute ischemia) was the indication for surgery in 90% (n = 617) of the overall cohort and 82% (n = 505) of those patients who presented with tissue loss/ulceration. Claudication accounted for less than 10% (n = 71) of patients undergoing surgery. Preoperatively, the majority of patients (90%; n = 618) lived at home; however, nearly half (45%; n = 308) needed assistance with ambulation.

Procedural characteristics

The majority of target vessels revascularized were at or below the knee (63%; n = 617). In the surgical group, the most frequent bypass was a common femoral to a below-knee target. Most often vein conduit was used (70%; n = 208) as single-segment vein (95%; n = 281). In the endovascular group, 55% (n = 375) of procedures were done on at or below knee vessels. Most often these patients had only one lesion treated (71%; n = 491) with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) alone (68%; n = 467). Of patients receiving more than one endovascular treatment, the second treatment was often cryoplasty, mechanical atherectomy, or laser atherectomy (Table II, A and B).

Table II.

| A, Surgical characteristics of hemodialysis-dependent (HD) patients undergoing open bypass | |

|---|---|

| Surgical open bypass (295 patients) | No. (%) |

| Origin vessel | |

| Femoral (ext iliac/com fem/profunda) | 188 (64) |

| AK (SFA/AK pop) | 70 (24) |

| BK (BK pop/tibial) | 36 (12) |

| Recipient vessel | |

| AK (SFA/profunda/AK pop/com fem) | 52 (18) |

| BK (BK pop/TP trunk/AT/PT/peroneal/DP ankle/PT ankle/tarsal/plantar) | 242 (82) |

| Bypass conduit | |

| Vein (no prosthetic) | 208 (71) |

| Prosthetic | 86 (29) |

| No. vein segments | |

| ≤1 segment | 281 (95) |

| >1 segment | 13 (4) |

| B, Characteristics of endovascular interventions among 394 hemodialysis-dependent (HD) patients with 686 total segments treated | |

|---|---|

| Endovascular intervention (394 patients, 686 segments) |

No. (%) |

| Target vessel | |

| Femoral (common iliac/ext iliac/com fem/profunda) | 120 (18) |

| AK (SFA) | 191 (28) |

| BK (pop/TP trunk/AT/PT/peroneal) | 375 (55) |

| Number of lesions treated | |

| 1 | 491 (72) |

| 2 | 95 (14) |

| ≥3 | 67 (10) |

| First treatment type | |

| PTA (PTA/cutting balloon) | 467 (68) |

| Stent (self-expand/balloon-expand/stent graft) | 102 (15) |

| Other (cryoplasty/laser atherect/mechanical atherect) | 89 (13) |

| Second treatment type | |

| PTA (PTA/cutting balloon) | 149 (22) |

| Stent (self-expand/balloon-expand/stent graft) | 125 (18) |

| Other (cryoplasty/laser atherect/mechanical atherect) | 384 (56) |

AK, Above knee; AK Pop, above-knee popliteal; AT, anterior tibial; BK, below-knee; Com Fem, common femoral; DP, dorsalis pedis; Ext, external;PT, posterior tibial; SFA, superficial femoral artery; TP, tibial-peroneal.

AK, Above knee; AT, anterior tibial; BK, below-knee; com fem, common femoral; ext, external; PT, posterior tibial; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; SFA, superficial femoral artery; TP, tibial-peroneal.

Short- and long-term outcomes

Short-term outcomes are displayed in Table III. Compared with open bypass, the endovascular group had lower rates of stroke (nonapplicable vs 1%), myocardial infarction (non-applicable vs 5%), and a higher likelihood of discharge to home (68% vs 41%; P < .001 for each).

Table III.

Short-term outcomes and disposition status for the overall cohort and by revascularization technique

| At discharge outcomes |

Overall (N = 689) |

Surgical open bypass (n = 295) |

Endovascular (n = 394) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death in hospital | 26 (4) | 15 (5) | 11 (3) | .149 |

| Any stroke | 2 (<1) | 2 (1) | NA | <.001 |

| MI | 14 (2) | 14 (5) | NA | <.001 |

| Disposition | ||||

| Home | 389 (57) | 120 (41) | 269 (68) | <.001 |

| Rehab unit | 160 (23) | 95 (32) | 65 (17) | |

| Nursing home | 109 (16) | 64 (22) | 45 (11) |

MI, Myocardial infarction.

Data are presented as number (%).

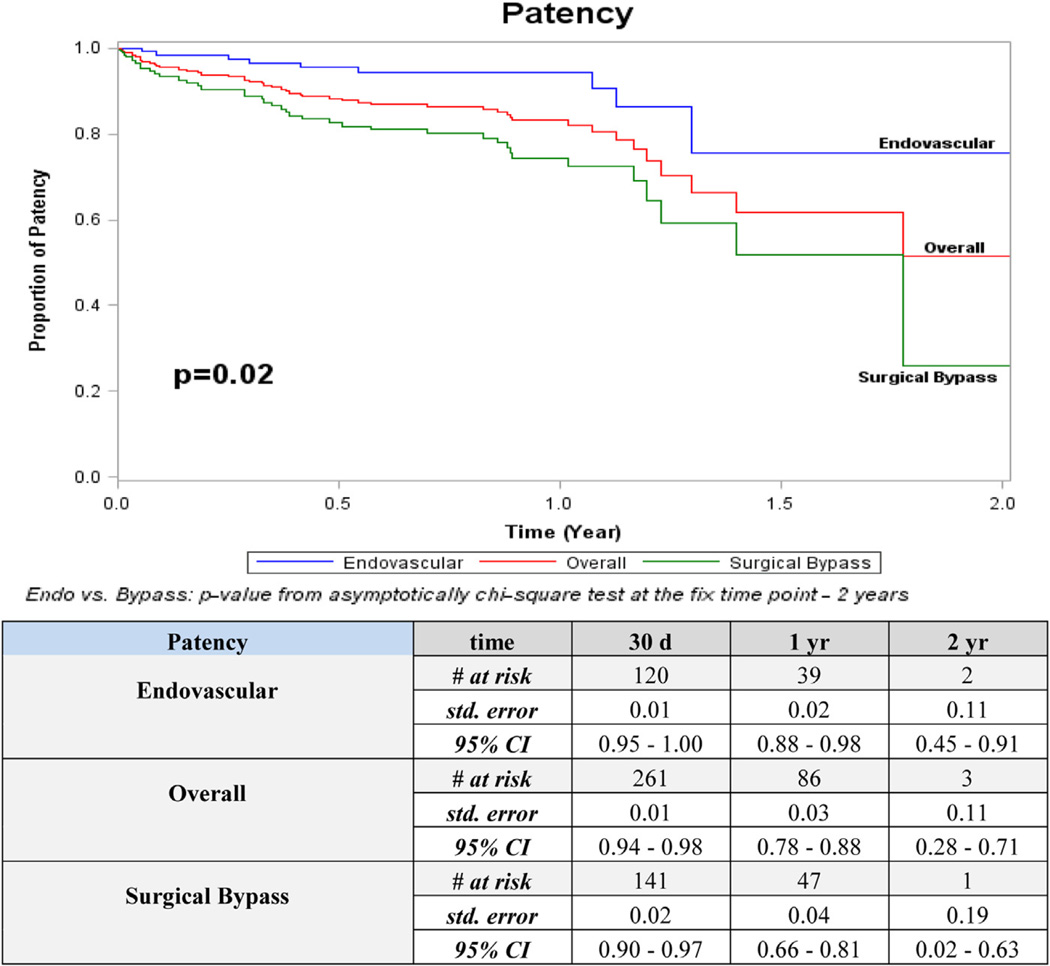

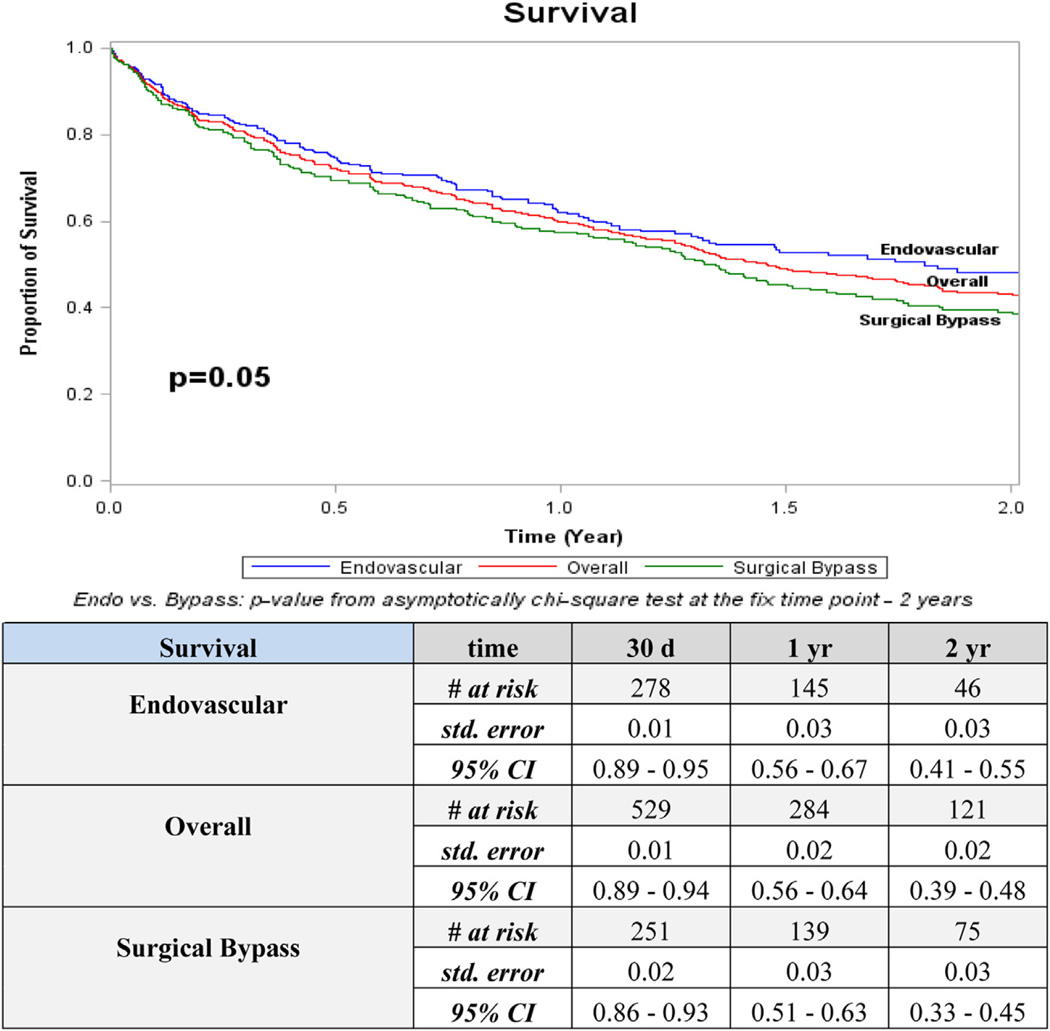

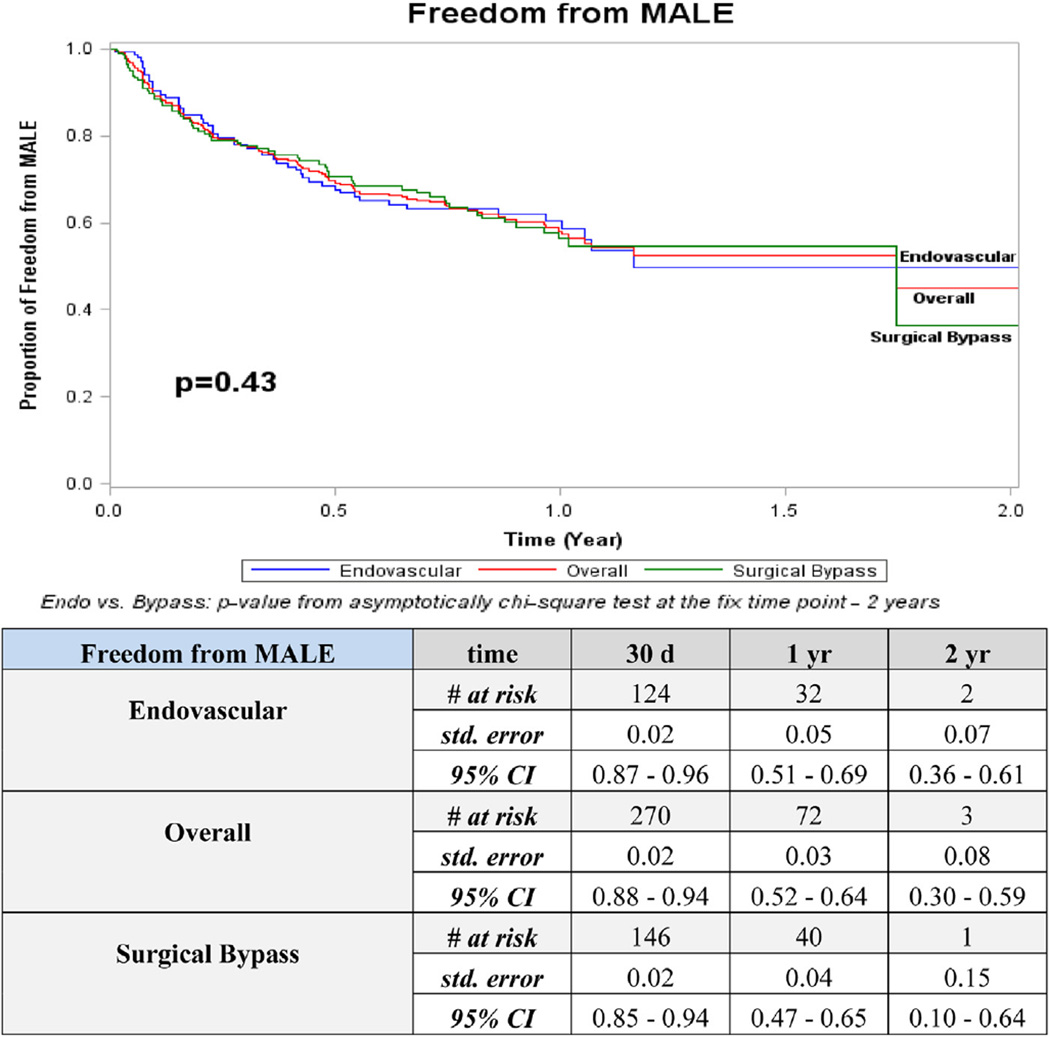

Overall 2-year outcomes for patency (52%) and freedom from MALE (45%) were higher than AFS (17%) and overall survival (43%; Figs 1–4). The distribution of events of AFS were analyzed, and nearly 80% of failures in both open surgical (78%; 155/198) and endovascular revascularization (80%; 134/167) were due to deaths, while the remaining 20% were attributed to amputation. Long-term outcomes were especially poor, with only 20% overall survival and <5% AFS at 5 years. Overall amputation-free rates at 1 and 2 years were 72% and 62%, respectively.

Fig 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves for patency. CI, Confidence interval; d, days; Endo, endovascular; std, standard; yr, year.

Fig 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves for survival. CI, Confidence interval; d, days; Endo, endovascular; std, standard; yr, year.

Patency was the sole statistically significant outcome that differed between open and endovascular revascularization strategies. At 2 years, 76% of endovascular revascularizations were patent compared with 26% for open surgical bypass (P = .02; Fig 1). This pattern persisted at all time points when below-knee recipient vessels of open bypass were compared with below-knee target vessels of the endovascular group (P = .003). Amputation with a patent limb occurred in 7% (n = 41) of the overall group, 5% (n = 15) in surgical bypass, and 9% (n = 26) in the endovascular group (P ≤ .001 between surgical bypass and endovascular). No other significant differences were detected between revascularization strategies for freedom from MALE, AFS, or overall survival.

Risk factors for death and amputation

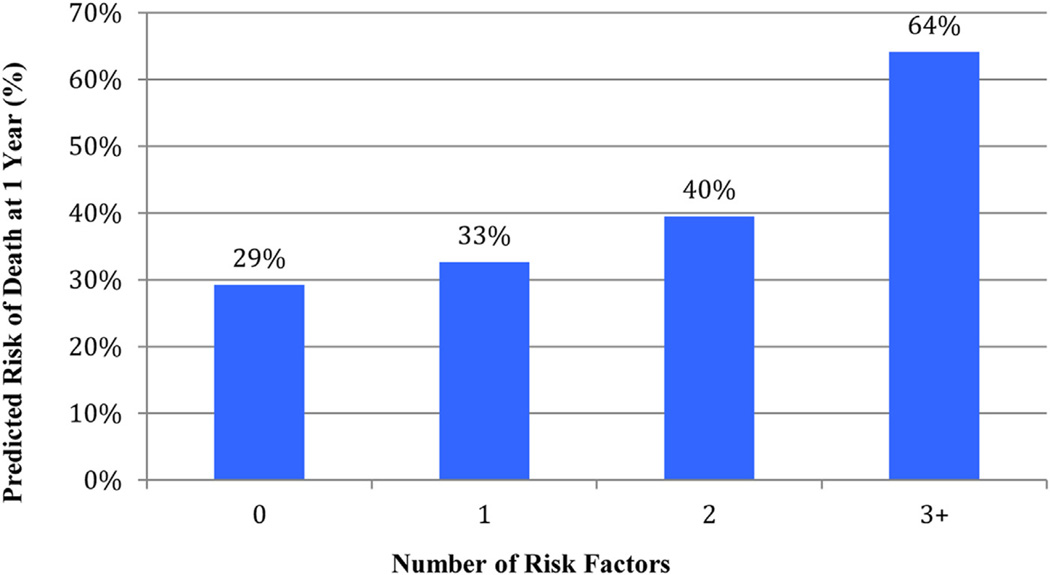

Cox proportional hazard models were performed to determine predictors of death among those without amputation (Table IV). Age ≥80 years old (HR 1.9; P < .01), coronary artery disease (CAD; HR, 1.5; P < .01), COPD (HR, 1.4; P = .01), dependent preoperative ambulation status (HR, 1.5; P < .01), and an indication of rest pain/tissue loss (HR, 1.8; P < .01) each were independent risk factors for mortality. The additive effect of multiple risk factors present showed a dramatic increase in predicted 1-year mortality (Fig 5). Rest pain/tissue loss was independently associated with amputation (HR, 4.1; P = .05).

Table IV.

Cox proportional hazard regression model for death in patients without amputation, overall cohort (N = 512)

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≥80 | 1.9 | 1.4–2.5 | <.01 |

| Any CAD | 1.5 | 1.2–1.9 | <.01 |

| Any COPD | 1.4 | 1.1–1.8 | .01 |

| Preoperative ambulatory status - wheelchair/bedridden | 1.5 | 1.1–2.1 | .01 |

| Indication - rest pain/tissue loss | 1.8 | 1.3–2.5 | <.01 |

CAD, Coronary artery disease; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HR, hazard ratio.

Fig 5.

Predicted risk of 1-year mortality by number of risk factors present.

DISCUSSION

This contemporary analysis of HD patients undergoing lower extremity revascularization demonstrates extremely finite survival in this frail patient population despite advances in both medical and interventional therapies. Moreover, utilization of endovascular vs open surgical therapy demonstrated no significant impact on overall survival. Furthermore, this analysis identified five independent and additive risk factors for 1-year mortality (age ≥80, CAD, COPD, preoperative ambulation status, rest pain/tissue loss), which may offer value in optimizing patient selection for revascularization.

HD has been well identified as a prominent risk factor associated with inferior outcomes in infrainguinal revascularization. Compared with non-ESRD patients, multiple studies examining lower extremity bypass have previously shown HD patients experience decreased patency, decreased limb salvage, and lower survival rates.9–15 Similarly, ESRD has been associated with inferior endovascular outcomes as well.16–19 However, these series tended to be smaller single center studies focusing on either open surgical1,2,4,5,15,20 or endovascular revascularization outcomes.16,18,21 Despite this, several studies and conventional wisdom have historically supported early vascular surgery referral and potential revascularization among ESRD patients.22–24 To date, however, there lacks direct comparison between open and endovascular techniques in contemporary practice of an HD-specific cohort. These data addressed this gap and examined outcomes of a regional HD cohort overall and by open and endovascular revascularization technique.

Accordingly, there are several important limb- and patient-related findings to highlight. Overall limb-rated outcomes were better than survival indices. Two-year freedom from MALE (45%), patency (52%), and amputation-free rates (62%) were within previously cited literature ranges.25–27 Indeed, the notion of proceeding with lower extremity revascularization in patients with ESRD and having 2-year patency and amputation-free rates over 50% is encouraging. These overall limb-related outcomes were higher than overall survival (43%) and AFS (17%) and consistent with observations of previous studies indicating acceptable limb salvage but poor survival in the HD population (Supplementary Table, online only).25–27

Limb-related outcomes were also examined by revascularization technique. Patency was the only category where a significant difference was detected between operative strategies. Interestingly, endovascular therapy showed better patency than open bypass at 2 years (76% vs 26%; P = .02). Previous studies have not stratified comparison of open and endovascular techniques in HD-specific cohorts. Although improved patency with endovascular revascularization may seemingly reinforce an “endovascular first” approach in highly morbid patients, those undergoing endovascular therapy in this study had fewer comorbidities when compared with open surgical candidates, thereby limiting comparison in this observational analysis.

Fewer than a quarter (17%) of the patients in our cohort achieved an AFS greater than 2 years, and less than half (43%) were alive at the same time point. These results remain within previous literature reported ranges at similar time points (AFS, 15%–23%2,25,26 and survival, 20%–50%1,2,4,7,28,29) and highlight a lack of temporal improvement in treatment of HD patients with critical limb ischemia.

Interestingly, stratification of survival and AFS showed no clinically substantial difference between open and endovascular methods (at 2 years, survival 39% vs 48% and AFS 19% vs 12%; P = nonsignificant for both). To date, this magnitude of comparison of open and endovascular techniques in a HD-specific cohort has not been performed. These data suggest no survival advantage between open or endovascular strategy in lower extremity revascularization of HD patients.

Our review of the failure modes in patients with HD and severe PAD confirmed most clinicians’ anecdotal experience that an overwhelming majority of HD patients fail due to death rather than amputation. In the overall cohort and by revascularization technique, 80% of failures were due to death, while amputation accounted for only 20%. These data further emphasize the inherent mortality associated with HD patients and the paramount importance of identifying those with survival potential to benefit from revascularization.

To this effect, multivariate risk factor analysis showed a near doubling of risk with age ≥80 years and four additional risk factors significantly associated with death at 1 year (Table IV). Furthermore, Fig 5 clearly demonstrates the additive effect of multiple risk factors and has several implications in helping surgeons choose which HD patients are the optimal candidates for revascularization. For example, a HD patient with three risk factors has nearly a two-out-of-three chance (64%) of not surviving 1 year after their procedure. Identification of such significant mortality risk is relevant to both the vascular surgeon and the patient as they decide on treatment options and develop realistic expectations. The same multivariate analysis for amputation showed rest pain and/or tissue loss highly associated with increased amputation. Combined, these risk analyses for death and failed limb salvage help identify when to avoid revascularization entirely and consider primary amputation or continued medical or palliative therapy.

Our study has several limitations. First, the VSGNE database is a voluntary quality improvement registry with self-reported outcomes. Although it is audited biannually and has shown 99% completeness in collecting bypass procedures,30 follow-up within the endovascular database was 58%. This may confound analysis of the endovascular group and limit the generalizability of these endovascular outcomes. Nonetheless, this is the largest study thus far comparing endovascular and open outcomes of a HD-specific population. As such, this work acts as preliminary data toward improving care of a high-risk population. Second, it was not possible to measure the effect of patients who received the alternative revascularization technique subsequent to their index procedure (ie, crossover). Less than 10% of patients in each cohort (7.8% of endovascular and 6.5% of open bypass patients) subsequently received a revascularization of the other technique. As this study has shown that most patients clinically succumb for indications unrelated to their PAD, it is unlikely that this small crossover group had a significant impact on our primary outcome, survival. Lastly, as this study is retrospective in nature, it is possible that there were significant anatomic differences between the open and endovascular groups. Thus, we remain unable to conclude the optimal treatment for lower extremity revascularization in HD patients. However, the goal was to describe contemporary outcomes and risk factors of open and endovascular revascularization in an HD-specific cohort rather than exclusively define best treatment modality.

CONCLUSIONS

Outcomes following lower extremity revascularization of HD patients remained poor and demonstrated little observational differences between endovascular and open bypass techniques. Death constituted the major mode of failure for both revascularization methods. Five independent risk factors for death (age ≥80 years, CAD, COPD, dependent preoperative ambulation status, and rest pain/tissue loss) were identified that showed an additive increased risk of 1-year mortality. These data provide a contemporary update on the outcomes of lower extremity revascularization among HD patients and offer a risk assessment tool to better identify patients with improved survival potential to benefit from revascularization.

Supplementary Material

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves for freedom from major adverse limb event (MALE). CI, Confidence interval; d, days; Endo, endovascular; std, standard; yr, year.

Fig 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves for amputation-free survival (AFS). CI, Confidence interval; d, days; Endo, endovascular; std, standard; yr, year.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

Presented at the 2014 Vascular Annual Meeting of the Society for Vascular Surgery, Boston, Mass, June 5-7, 2014.

Additional material for this article may be found online at www.jvascsurg.org.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: JF, PG, DS, AH

Analysis and interpretation: JF, PG, DS, VP, BN, JK, YZ, AH

Data collection: JF, PG, DS, YZ

Writing the article: JF, PG, DS

Critical revision of the article: JF, PG, DS, VP, BN, JK, YZ, AH

Final approval of the article: JF, PG, DS, VP, BN, JK, YZ, AH

Statistical analysis: JF, PG, DS, YZ

Obtained funding: JF, PG, DS, AH

Overall responsibility: JF

REFERENCES

- 1.Baele HR, Piotrowski JJ, Yuhas J, Anderson C, Alexander JJ. Infrainguinal bypass in patients with end-stage renal disease. Surgery. 1995;117:319–324. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80208-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biancari F, Kantonen I, Matzke S, Alback A, Roth WD, Edgren J, et al. Infrainguinal endovascular and bypass surgery for critical leg ischemia in patients on long-term dialysis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2002;16:210–214. doi: 10.1007/s10016-001-0161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leers SA, Reifsnyder T, Delmonte R, Caron M. Realistic expectations for pedal bypass grafts in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Vasc Surg. 1998;28:976–980. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70023-0. discussion: 981-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korn P, Hoenig SJ, Skillman JJ, Kent KC. Is lower extremity revascularization worthwhile in patients with end-stage renal disease? Surgery. 2000;128:472–479. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyerson SL, Skelly CL, Curi MA, Desai TR, Katz D, Bassiouny HS, et al. Long-term results justify autogenous infrainguinal bypass grafting in patients with end-stage renal failure. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:27–33. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.116350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Townley WA, Carrell TW, Jenkins MP, Wolfe JH, Cheshire NJ. Critical limb ischemia in the dialysis-dependent patient: infrainguinal vein bypass is justified. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2006;40:362–366. doi: 10.1177/1538574406293739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orimoto Y, Ohta T, Ishibashi H, Sugimoto I, Iwata H, Yamada T, et al. The prognosis of patients on hemodialysis with foot lesions. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58:1291–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajagopalan S, Dellegrottaglie S, Furniss AL, Gillespie BW, Satayathum S, Lameire N, et al. Peripheral arterial disease in patients with end-stage renal disease: observations from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Circulation. 2006;114:1914–1922. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owens CD, Ho KJ, Kim S, Schanzer A, Lin J, Matros E, et al. Refinement of survival prediction in patients undergoing lower extremity bypass surgery: stratification by chronic kidney disease classification. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:944–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodney PP, Nolan BW, Schanzer A, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Stanley AC, Stone DH, et al. Factors associated with death 1 year after lower extremity bypass in Northern New England. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodney PP, Nolan BW, Schanzer A, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Bertges DJ, Stanley AC, et al. Factors associated with amputation or graft occlusion one year after lower extremity bypass in northern New England. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta PK, Ramanan B, Lynch TG, Sundaram A, MacTaggart JN, Gupta H, et al. Development and validation of a risk calculator for prediction of mortality after infrainguinal bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:372–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McPhee JT, Nguyen LL, Ho KJ, Ozaki CK, Conte MS, Belkin M. Risk prediction of 30-day readmission after infrainguinal bypass for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2013;57:1481–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arvela E, Soderstrom M, Alback A, Aho PS, Tikkanen I, Lepantalo M. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) as a predictor of outcome after infrainguinal bypass in patients with critical limb ischemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;36:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramdev P, Rayan SS, Sheahan M, Hamdan AD, Logerfo FW, Akbari CM, et al. A decade experience with infrainguinal revascularization in a dialysis-dependent patient population. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:969–974. doi: 10.1067/mva.2002.128297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brosi P, Baumgartner I, Silvestro A, Do DD, Mahler F, Triller J, et al. Below-the-knee angioplasty in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Endovasc Ther. 2005;12:704–713. doi: 10.1583/05-1638MR.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kudo T, Chandra FA, Ahn SS. Long-term outcomes and predictors of iliac angioplasty with selective stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:466–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandez N, McEnaney R, Marone LK, Rhee RY, Leers S, Makaroun M, et al. Predictors of failure and success of tibial interventions for critical limb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.04.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iida O, Nakamura M, Yamauchi Y, Kawasaki D, Yokoi Y, Yokoi H, et al. Endovascular treatment for infrainguinal vessels in patients with critical limb ischemia: OLIVE registry, a prospective, multicenter study in Japan with 12-month follow-up. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:68–76. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.975318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peltonen S, Biancari F, Lindgren L, Makisalo H, Honkanen E, Lepantalo M. Outcome of infrainguinal bypass surgery for critical leg ischaemia in patients with chronic renal failure. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1998;15:122–127. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(98)80132-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werneck CC, Lindsay TF. Tibial angioplasty for limb salvage in highrisk patients and cost analysis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009;23:554–559. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortmann J, Gahl B, Diehm N, Dick F, Traupe T, Baumgartner I. Survival benefits of revascularization in patients with critical limb ischemia and renal insufficiency. J Vasc Surg. 2012;56:737–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.02.049. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Hare AM, Bertenthal D, Sidawy AN, Shlipak MG, Sen S, Chren MM. Renal insufficiency and use of revascularization among a national cohort of men with advanced lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:297–304. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01070905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lantis JC, 2nd, Conte MS, Belkin M, Whittemore AD, Mannick JA, Donaldson MC. Infrainguinal bypass grafting in patients with end-stage renal disease: improving outcomes? J Vasc Surg. 2001;33:1171–1178. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.115607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biancari F, Arvela E, Korhonen M, Soderstrom M, Halmesmaki K, Alback A, et al. End-stage renal disease and critical limb ischemia: a deadly combination? Scand J Surg. 2012;101:138–143. doi: 10.1177/145749691210100211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakano M, Hirano K, Iida O, Soga Y, Kawasaki D, Suzuki K, et al. Prognosis of critical limb ischemia in hemodialysis patients after isolated infrapopliteal balloon angioplasty: results from the Japan below-the-knee artery treatment (J-BEAT) registry. J Endovasc Ther. 2013;20:113–124. doi: 10.1583/11-3782.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albers M, Romiti M, De Luccia N, Brochado-Neto FC, Nishimoto I, Pereira CA. An updated meta-analysis of infrainguinal arterial reconstruction in patients with end-stage renal disease. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johnson BL, Glickman MH, Bandyk DF, Esses GE. Failure of foot salvage in patients with end-stage renal disease after surgical revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:280–285. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(95)70142-7. discussion: 285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez LA, Goldsmith J, Rivers SP, Panetta TF, Wengerter KR, Veith FJ. Limb salvage surgery in end stage renal disease: is it worthwhile? J Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;33:344–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cronenwett JL, Likosky DS, Russell MT, Eldrup-Jorgensen J, Stanley AC, Nolan BW, et al. A regional registry for quality assurance and improvement: the Vascular Study Group of Northern New England (VSGNNE) J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:1093–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.012. discussion: 1101-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.