Abstract

Soil ecosystems worldwide are subjected to marked modifications caused by anthropogenic disturbances and global climate change, resulting in microbial diversity loss and alteration of ecosystem functions. Despite the paucity of studies, restoration ecology provides an appropriate framework for testing the potential of manipulating soil microbial communities for the recovery of ecosystem functioning. We used a reciprocal transplant design in experimentally altered microbial communities to investigate the effectiveness of introducing microbial communities in degraded soil ecosystems to restore N-cycle functioning. Microbial diversity loss resulted in alternative compositional states associated with impaired N-cycle functioning. Here, the addition of complex microbial communities to these altered communities revealed a pivotal role of deterministic community assembly processes. The diversity of some alternative compositional states was successfully increased but without significant restoration of soil N-cycle functioning. However, in the most degraded alternative state, the introduction of new microbial communities caused an overall decrease in phylogenetic diversity and richness. The successful soil colonization by newly introduced species for some compositional states indicates that priority effects could be overridden when attempting to manipulate microbial communities for soil restoration. Altogether, our result showed consistent patterns within restoration treatments with minor idiosyncratic effects. This suggests the predominance of deterministic processes and the predictability of restoration trajectories, which could be used to guide the effective management of microbial community assemblages for ecological restoration of soils.

Introduction

Soil microorganisms form one of the largest biodiversity reservoirs on earth. They also have essential roles in ecosystem functions such as biogeochemical cycling (Falkowski et al., 2008; Wagg et al., 2014). However, biodiversity loss is now recognized as one of the main threats confronted by soils (Commission of the European Community, 2006), with increasing evidence that this can alter ecosystem functioning and stability (Bardgett and van der Putten, 2014; Wagg et al., 2014). Only recently, soil microorganisms have become of interest in restoration ecology as key soil engineers that may be manipulated to re-establish biodiversity and functions in degraded ecosystems (Young et al., 2005; Heneghan et al., 2008). Nevertheless, most work in restoration ecology is still focused on plants (Kardol and Wardle, 2010). Microorganisms are at best used to study the belowground impact of re-introducing flora (Smith et al., 2003) or to promote plant establishment through symbiotic interactions (Requena et al., 2001). For example, Kardol et al. (2008) investigated whether the introduction of microorganisms by spreading soil from a donor late succession site would facilitate grassland restoration. The unsuccessful establishment of late successional plant species was attributed to poor colonization of the soil by the introduced microorganisms. On the other hand, Smith et al. (1998) found that inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi promotes the development of early successional tallgrass prairie communities. These discrepancies illustrate the need for studies using a microbial community-wide restoration approach to assess the establishment and survival of microorganisms for successful ecological restoration of soils.

Restoring soil functioning is challenging, as microbial ecosystem dynamics are complex, nonlinear and partly unpredictable (Nemergut et al., 2013). Historical contingency, known as priority effects, varies between species and environments and can prevent colonization by late-arriving species (Vannette and Fukami, 2014). The occurrence of alternative stable states during colonization processes can also impede the complete recovery of community structure and ecosystem functions, as shown in other systems (Moreno-Mateos et al., 2012). However, our understanding of the role of species interactions and of idiosyncratic effects in the restoration trajectory of microbial biodiversity and functioning is limited despite being crucial (Harris, 2009; Laughlin, 2014). Here, we examined the effectiveness of introducing microbial communities in altered communities, to recover soil biodiversity and functioning. We hypothesized that priority effects and the biodiversity level of the already-established communities but also of the newly introduced communities are of importance for community assembly and successful restoration. The influence of the relatedness between the already-established communities and the newly introduced communities on priority effects was assessed using a reciprocal transplant experiment by introducing microbial communities from two different soils into a third sterile soil previously colonized by each of the other community. We focused on nitrogen cycling as a model ecosystem function because of its importance for plant nutrition and recent evidence that it has crossed a critical threshold in terms of safe operating space for humanity (Rockstrom et al., 2009).

Materials and methods

Soil sampling and experimental design

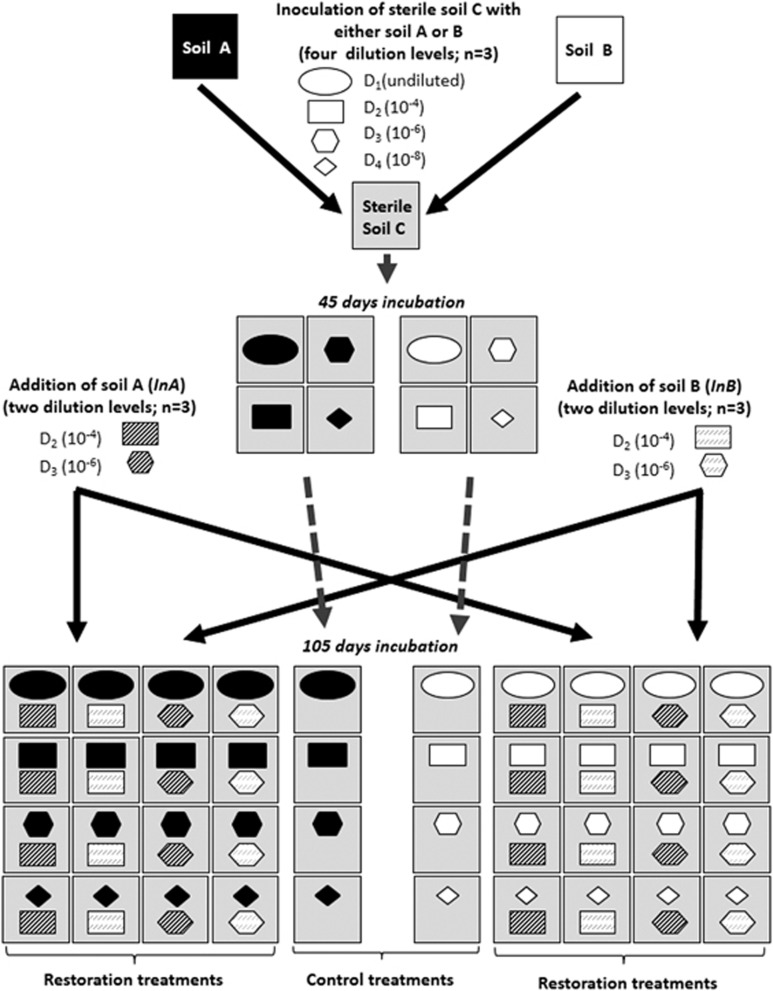

Soil samples were collected from three sites: Epoisses, France (47° 30' 22.1832'' N, 4° 10' 26.4648'' E), Ulleråker, Sweden (59° 49' 54.5700'' N, 17° 39' 1.9008'' E) and Lusignan, France (46° 26' 4.9560'' N, 0° 7' 20.8380'' E), hereafter named A, B and C, respectively. Soil properties are described in Table S1. At each sampling site, soil was collected from three locations ca. 20 m apart from one another, by pooling five soil cores (20 cm depth) from 1 m × 1 m area at each location. All following steps were conducted by keeping the three replicate samples for each soil independent. All soils were sieved to 4 mm. Soil C was sterilized by γ-radiation (35 kGy; Conservatome, Dagneux, France) and inoculated with dilutions of microbial communities from either soil A or B to avoid any ‘home-field advantage'. Soil suspensions were made for both soils A and B by mixing 100 g equivalent dry mass soil with 150 ml sterile distilled water using a ultraviolet-sterilized blender. Soil suspensions were then serially diluted to create a diversity gradient of soil microorganisms ranging from undiluted (D1) to diluted 10−4 (D2), 10−6 (D3) and 10−8 (D4) suspensions, and 5 ml of suspension was subsequently inoculated into 147 ml plasma flasks containing 50 g dry of sterile soil C (n=21) for each of the eight combinations of inoculum soil type and inoculum dilution level (Figure 1) to reach 70% of the water-holding capacity. The plasma flasks were then closed with sterile lids and the inoculated microcosms incubated at 20 °C at a soil moisture ranging between 60% and 70% of the water-holding capacity. At days 44 and 105, three replicates of each combination of inoculum soil type and inoculum dilution were used for analyses of total bacterial diversity and composition, abundance of N-cycle microbial guilds and determination of soil extractable ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−) pool sizes.

Figure 1.

Experimental design. Diluted suspensions (ovals: undiluted D1, rectangles: 10−4 dilution D2, hexagons: 10−6 dilution D3, diamonds: 10−8 dilution D4) of two soil microbial communities A (black color) and B (white color) were separately inoculated into a sterile soil C (gray color) at day 0. At day 45, established microcosms of each dilution treatment and each soil were re-inoculated (InA or InB) in triplicates with two diluted suspensions (shaded rectangles: 10−4 dilution D2, shaded hexagons: 10−6 dilution D3) of either soil A (black shades) or B (gray shades) and incubated until day 105. Three replicate microcosms of each dilution level and of each microbial community were not re-inoculated and used as controls at day 105.

Ecological rescue experiment

To assess the effect of restoration of microbial diversity, all microcosms were re-inoculated after 45 days with a suspension of either soil A or B at two dilution levels (10−4: D2, and 10−6: D3), in a reciprocal transplant design as described below (Figure 1). Thirty-two treatment combinations were generated, that are eight combinations of inoculum soil type (A or B) and inoculum dilution level (D1, D2, D3, or D4) × four combinations of restoration soil type (A or B) and restoration dilution level (D2 or D3), with n=3 for each combination. Microcosms were incubated at 20 °C and maintained at between 60% and 70% water-holding capacity by regular addition of sterile water. To compensate for decreasing nutrient availability in our closed systems, all microcosms were watered at day 45 with 5 ml of a sterile soil nutrient solution based on a dilution of the sterile soil C. This was obtained by mixing 100 g equivalent dry mass of soil C with 150 ml sterile distilled water in an ultraviolet-sterilized blender, centrifuging (4700 rpm, 20 min, 4 °C) and filtering the soil supernatant using a sterile membrane (0.45 μM pore size). After 105 days, the soils from all the 120 remaining microcosms were used to determine the diversity of the total microbial community, the abundance of N-cycle microbial guilds, soil extractable ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−) pool sizes, and total mineral N content.

Nitrogen cycling

Soil nitrate and ammonium concentrations, which reflect the net balance between actual N fluxes resulting from different N-transforming processes, were used as proxies of the overall functioning of the N-cycle in soil. Mineral nitrogen pools (NO3− and NH4+) present in the soil were extracted using 50 ml of KCl 1 M that was added to ca. 10 g fresh soil, shaken (80 rpm for 1 h at room temperature), filtered and kept frozen until quantification according to ISO 14256-2. Quantification was performed using at least two blanks in each series by colorimetry (BPC global 240 photometer).

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted from 250 mg dry-weight soil samples according to ISO standard 11063 ‘Soil quality-Method to directly extract DNA from soil samples' (Petric et al., 2011). In brief, samples were homogenized in 1 ml extraction buffer (1 M Tris–HCl pH=8, 0.5 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid pH=8, 1 M NaCl, 20% polyvinylpyrrolidone, 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate) for 30 s at 1600 rpm in a mini-bead beater cell disrupter Mikro-DismembratorS (B. Braun, Biotech International, Germany) and incubated at 70 °C for 15 min with vortexing every 5 min. Soil and cell debris were removed by centrifugation (14 000 g, 1 min, 4 °C). Proteins were removed by incubation for 10 min on ice with 1/10 volume with sodium acetate 3 M pH=5.5. Nucleic acids were precipitated for 3 h at −20 °C with ice-cold isopropanol and the resulting pellet was suspended in 100 μl of TE pH=8 at 4 °C overnight. Precipitated DNA was then double-purified using polyvinylpyrrolidone (Sigma-Aldrich, UK) and Sepharose 4B (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) spin columns. Finally, soil DNA integrity was checked by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel and total DNA concentration in each sample was quantified by fluorometry using a Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Quantification of microbial communities

Total bacterial and fungal communities were quantified using 16S rRNA and ITS primer-based qPCR assays, respectively (Muyzer et al., 1993; Ochsenreiter et al., 2003; Schoch et al., 2012). Quantification of the bacterial and archaeal ammonia oxidizers was performed according to Tourna et al. (2008) and Leininger et al. (2006), whereas quantification of denitrifiers was performed according to Henry et al. (2004 and 2006). For this purpose, the genes encoding catalytic enzymes of ammonia-oxidation (bacterial and archaeal amoA) and of nitrite reduction (nirK, nirS) were used as molecular markers. Reactions were carried out in a ViiA7 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Quantification was based on the increasing fluorescence intensity of the SYBR Green dye during amplification. The real-time PCR assays were carried out in a 15 μl reaction volume containing SYBR green PCR Master Mix (Absolute Blue QPCR SYBR Green Low Rox Mix, Thermo Fisher Scientific (Villebon sur Yvette, France), 1 μM of each primer, 250 ng of T4 gene 32 (QBiogene, Illkirch, France) and 0.5 ng of DNA as previously described (Bru et al., 2011). Three independent replicates were used for each real-time PCR assay. Standard curves were obtained using serial dilutions of linearized plasmids containing appropriated cloned targeted genes from bacterial strains or environmental clones. PCR efficiency for the different assays ranged from 70 to 99%. No template controls gave null or negligible values. The presence of PCR inhibitors in DNA extracted from soil was estimated by mixing a known amount of standard DNA with soil DNA extract prior to qPCR. No inhibition was detected in any case.

Amplicon generation and 454 pyrosequencing

A two-step PCR approach was used for amplification of the V3–V4 bacterial hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene according to Berry et al. (2011). The first step was to run on three subsamples that were subsequently pooled. It consisted of 1 μM forward primer 515F 5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′, 1 μM reverse primer 806R 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′ (Eurogentec Seraing, Belgium), together with 10 × buffer with MgSO4 (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Baines, France), 1U Pfu DNA polymerase, 2 μM dNTPs (MP Biomedicals, Illkrich, France), 250 ng T4 gp32 bacteriophage (MP Biomedicals) and 0.5 ng DNA template in a final volume of 25 μl. Reaction conditions were as follows: 2 min at 95 °C followed by 20 cycles of 30 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 53 °C and 60 s at 72 °C on an MJ Research PTC-200 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). In the second step, 1 μl of the pooled PCR products of the first step was amplified in triplicate in a 10-cycle PCR using the forward primers preceded by 10 basepair-long barcodes, the sequencing key and the forward sequencing adapter; the reverse primers being preceded by the sequencing key and the reverse sequencing adapter only. The final PCR products were pooled and extracted from 2% agarose gel with the QIAEX II kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and finally quantified using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit (Invitrogen). Pyrosequencing was performed by Genoscreen sequencing service (Lille, France) on a Roche 454 FLX Genome Sequencer using Titanium chemistry (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France).

Bioinformatic analysis of the 16S rRNA amplicons

The sequences obtained were analyzed using QIIME pipeline software (Caporaso et al., 2010b). Sequences of poor quality (score<25 on a 50 basepair sliding window) or shorter than 240 base pairs were removed. Reference-based chimera detection was performed using Greengene's representative set of 16S sequences and >1'183'662 quality-filtered reads were clustered in operational taxonomy units (OTUs) at 97% similarity using USEARCH (Edgar, 2010). Representative sequences for each OTU (4'318 OTUs retrieved) were then aligned using PyNAST (Caporaso et al., 2010a) and their taxonomy assigned using the greengenes database (http://greengenes.lbl.gov/cgi-bin/nph-index.cgi). A phylogenetic tree was then constructed using FastTree (Price et al., 2009). Raw sequences were deposited at the NCBI under the accession number SRP057201. The process of raw sequence submission was performed using the make.sra command of Mothur software (Schloss et al., 2009).

Diversity metrics, that is, Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity (Faith, 1992), richness (observed species) and evenness (Simpson's reciprocal index), describing the structure of microbial communities were calculated based on rarefied OTU tables (1500 sequences per sample). Unweighted and weighted UniFrac distance matrices (Lozupone and Knight, 2005) were also computed to detect global variations in the composition of microbial communities. Only Principal Coordinates Analyses of unweighted UniFrac distance matrix is displayed.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in R Studio (version 3.0.2) using the following R packages: vegan (Oksanen et al., 2013), RColowBrewer (Neuwirth, 2011), gplots (Bonebakker et al., 2012), car (Fox et al., 2014), fdrtool (Klaus et al., 2014) and igraph (Csardi and Nepusz, 2006). Differences in gene copy abundance (16S rRNA, AOA and AOB), total nitrogen, ammonium and nitrate concentrations, and α-diversity indexes were tested using ANOVAs followed by Tukey's honestly significant difference (HSD) tests. Variance-partitioning techniques were used to explain variations of different nitrogen pools (that is, ammonium or nitrate) by variations of microbial communities, based on their abundance (16S rRNA, AOA and AOB), structure (retrieved as coordinates on the first two axes of an unweighted UniFrac-based NMDS) and diversity (observed species and Faith's PD). This analysis was performed using the varpart function of the vegan R package.

To reduce the search space for co-occurrence testing, we focused our analysis on OTUs for which the total abundance (summed up in the panel of 48 control samples) was above 48 counts and that had been detected in at least half of the samples. Thus, 244 OTUs were kept for subsequent analyses. For network inference, we considered a valid co-occurrence between two OTUs to be detected as a robust (Spearman's ρ>0.65 or <−0.65) and significant correlation (false discovery rate<0.05). We further sought community structure within the main connected network using the Modulated Modularity Clustering tool (Stone and Ayroles, 2009) based on Spearman's correlation. Modulated modularity clustering was performed using the web interface provided (http://mmc.gnets.ncsu.edu/). A ‘nearest-shrunken centroid' approach (Tibshirani et al., 2002) was performed to detect OTUs that were particularly representative of each dilution level using the pamr library under the R software.

Results and Discussion

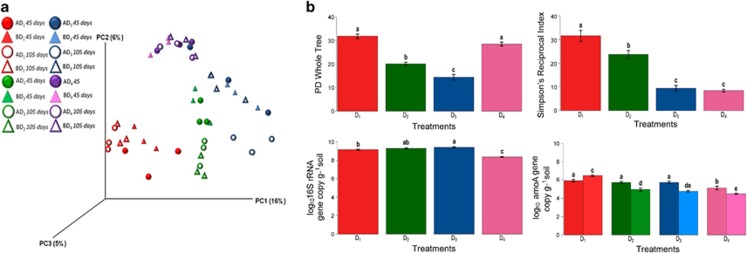

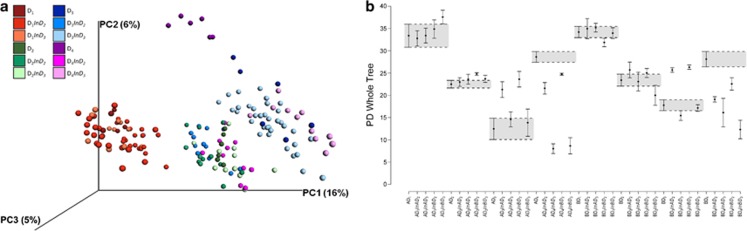

Degraded soil microbial diversity states were generated using a removal-by-dilution approach by introducing serial dilutions (undiluted: D1, 10−4: D2, 10−6: D3, 10−8: D4) of two different soil microbial communities (A: Epoisses, France and B: Ulleråker, Sweden) into a pre-sterilized soil (C, Lusignan; France) to avoid ‘home-field advantage' that is, an advantage of microorganisms returning to their native soil (Figure 1, Supplementary Table S1). This controlled experimental strategy also offers the advantage of circumventing confounding effects owing to the soil type, which are inherent to naturally assembled communities with different diversity levels. Microbial community assembly and diversity was assessed by sequencing 16S rRNA gene after 45 and 105 days of incubation. Of the 721 and 839 observed OTUs present in the undiluted inocula from soils A and B, respectively, ~45% and 44% were detected in the soil after 105 days (Supplementary Table S2). Analyses of the phylogenetic structure of soil suspension communities used for inoculation also showed a significantly larger weighted UniFrac distance of 0.3 between inocula from soils A and B, compared with a distance of ~0.2 between the resulting soil communities after colonization (Supplementary Figure S1). This indicates that the physico-chemical properties of the receiving soil regulated the recolonization patterns of inoculated microbial communities, which is consistent with previous studies (Delmont et al., 2014). Similarly, principal coordinates analysis of unweighted UniFrac distances between samples revealed a stronger clustering of the established microbial communities according to their initial dilution levels rather than to their soil of origin (Figure 2a). This strong clustering between replicate samples also indicates reproducible assemblies of microbial communities. Altogether, these results suggest that microbial communities were assembled via deterministic rather than stochastic processes (Nemergut et al., 2013), and provide evidence for habitat filtering, that is, the non-random establishment and survival of individuals with respect to abiotic local characteristics.

Figure 2.

Abundance, diversity and structure of altered bacterial communities. (a) Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) of the unweighted UniFrac distance matrix representing differences in community structure of control microcosms at four dilution levels. Triangles and circles indicate control microcosms inoculated with communities from soils A and B, respectively. D1, D2, D3 and D4 dilutions are represented by red, green, blue and pink colors, respectively, with closed and open symbols at days 45 and 105, respectively. (b) Diversity levels and community abundances at four dilution levels across soil communities A and B. Faith's PD and Simpson's reciprocal index are represented, as well as abundances of total bacteria (16S rRNA), and ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA, dark colors) and bacteria (AOB, light colors). Values are mean±s.d. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences according to Tukey's test (α=0.05). Colors are the same as in a.

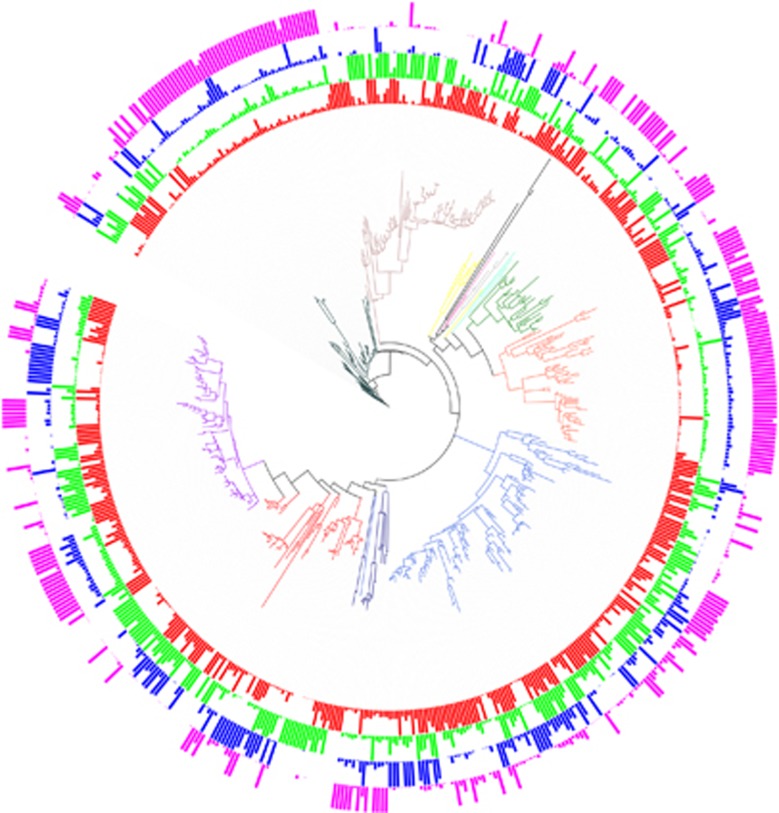

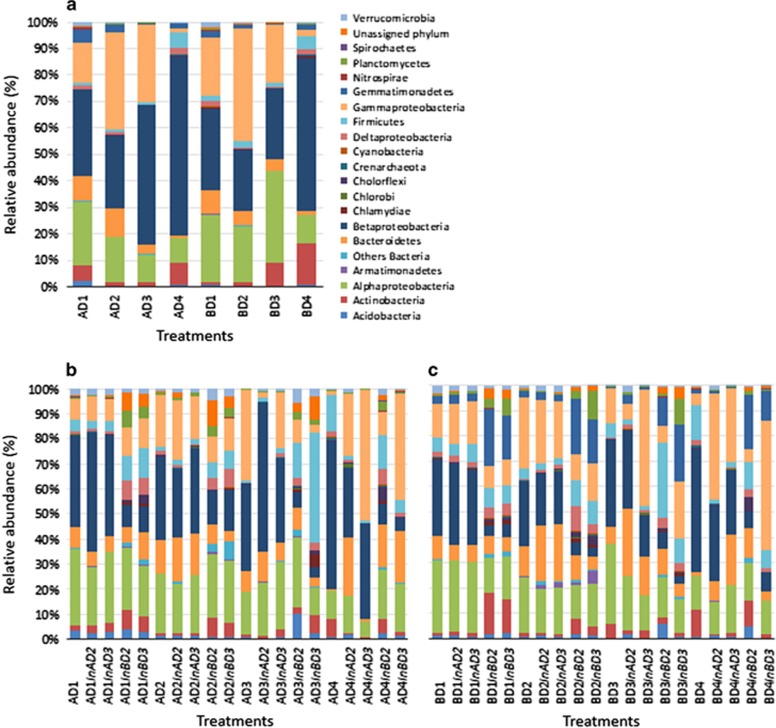

Although increased dilution led to a significant decrease in overall bacterial diversity, we observed different patterns depending on the diversity index considered. Simpson's reciprocal index significantly decreased from D1 to D3, whereas Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity index was significantly greater in D1 and D4 microcosms (Figure 2b). This was concomitant with a decrease in the relative abundance of certain OTUs between D1 and D3 along with greater abundance of phylogenetically diverse OTUs in D4 (Figure 3). Likewise, community composition analyses suggest that dilution followed by interspecific interactions during the colonization process (Martorell and Freckleton, 2014) resulted in two alternative community compositional states (Figure 3 and 4a, Supplementary Table S2). The first state, observed in D1, D2 and D3, consisted of a gradually impoverished community with decreasing phylogenetic diversity and species richness levels (Figure 2b and Supplementary Table S2). In this state, microbial communities were dominated by α-, β- and γ-proteobacteria (Figure 4a). Network analysis revealed significant negative co-occurrence between members of γ-proteobacteria and members of the Actinobacteria and Firmicutes phyla (Supplementary Figure S2). A nearest-shrunken centroid approach detected members of the γ-proteobacteria as indicator species of the D1 state (Supplementary Figure S2). The second state, found in D4 microcosms, was characterized by a high phylogenetic diversity but a low evenness (Figure 2b and Supplementary Table S2). A stronger dominance of the β−Proteobacteria at the expense of the α and γ-Proteobacteria (Figure 4a) was observed for this state. OTUs mainly belonged to the genus Ralstonia, with also members of the Actinobacteria and Firmicutes phyla detected as indicator species of D4. In contrast to D1, D2 and D3, this altered community in D4 did not reach soil-carrying capacity, as reflected by its significantly lower 16S rRNA gene copy numbers after both 45 and 105 days (Figure 2b and Supplementary Figure S3). This suggests that the species present in this second state were not capable of exploiting all the niches available in the sterilized soil, even after 3-month incubation period. Similarity in community composition and diversity levels for all dilution treatments between incubation days 45 and 105 highlights the stability of the two compositional states over time (Figure 2a and Supplementary Table S2). Persistence of a low biodiversity state has been shown for plant communities after cessation of nutrient enrichment (Isbell et al., 2013). However, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first experimental demonstration of the existence of alternative and stable states in bacterial communities caused by a loss of biodiversity and distinct assembly during soil colonization.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic placement and relative abundance of 16S rRNA OTUs at four different dilution levels across soil communities A and B. Relative abundance at the D1, D2, D3 and D4 dilution levels from both bacterial communities are represented by red, green, blue and pink plain circles, respectively. The relative abundance of each OTU has been normalized to the maximum abundance of this OTU across dilutions and is therefore bounded between 0 and 1. Branches are colored according to the phylum assignment of each OTU (Acidobacteria: yellow, Actinobacteria: orange red, Bacteroidetes: rosy brown, Chloroflexi: aquamarine, Firmicutes: dark green, Gemmatimonadetes: light green, Planctomycetes: black, α-proteobacteria: light blue, β-proteobacteria: purple, δ-proteobacteria: navy blue, γ-proteobacteria: red and Verrucomicrobia: gray). The online tool Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) was used to prepare this figure (http://itol.embl.de/).

Figure 4.

Community composition in control and restored microcosms. (a) At day 45 in control microcosms established with communities from soils A and B, at different dilution levels. (b) At day 105 in control and restored microcosms containing the pre-established communities from soil A. Samples are labeled according to the following scheme: AD1InAD2 stands for microcosms established with Dilution 1 from soil A and re-inoculated with Dilution 2 from soil A. (c) At day 105 in control and restored microcosms containing the pre-established communities from soil B. Samples are labeled according to the following scheme: BD1InAD2 stands for microcosms established with Dilution 1 from soil B and re-inoculated with Dilution 2 from soil A.

The functional impact of the induced loss of diversity was strong and significant on soil N cycling, as showed by changes in NH4+ and NO3− pool sizes (Supplementary Figure S4). After both 45 and 105 days, the significant decrease in total mineral nitrogen pool size from D1 to D4 was accompanied by a drastic switch in the net balance between mineral nitrogen forms, from dominant nitrate forms in the D1 communities to an altered N-cycle with dominant ammonium forms in the more diluted microbial communities (Supplementary Figure S4). These results indicate a rather stable N pool equilibrium in our experimental system, with soil N cycling remaining impaired over time. Lower NO3− pools are consistent overall with a significantly reduced abundance of bacterial and archaeal ammonia oxidizers (Figure 2b). A significant decrease in the abundance of denitrifiers that can reduce NO3− into N2 was also observed (Supplementary Figure S5). Based on these results, we hypothesize that the degraded microbial community states in D2, D3 and D4 microcosms resulted primarily in altered oxidation of ammonium into nitrate by nitrification, compromising N cycling and resulting in NH4+ accumulation. This is in agreement with theoretical predictions suggesting that narrow processes carried out by phylogenetically constrained groups of microorganisms, such as nitrification, are more sensitive to disturbance than broad processes carried out by many different microbial groups, such as mineralization (Griffiths et al., 2001; Schimel and Schaeffer, 2012). We observed a significant gradual reduction of soil NH4+ pool size in the D2, D3 and D4 microcosms as dilution increased (Tukey's HSD test, P<0.05), likely reflecting the hindered capacity of altered soil microbial communities to degrade organic nitrogen. This gradual decrease was not related to changes in the abundance of fungi, which are important players in soil mineralization processes, as no significant differences were observed between the D2, D3 and D4 microcosms (Supplementary Figure S6). This indicates that even broad processes such as mineralization may be hampered by high rates of species loss. By combining abundance, diversity and community structure data, and using variance-partitioning techniques (Legendre and De Caceres, 2013), we identified the diversity level × community structure interaction as the main driver (contributing ca. 28% of the variance) of observed differences in N-cycle functioning. This confirms that both species richness and community membership hold a pivotal role in the regulation of ecosystem functioning (Peter et al., 2011; Philippot et al., 2013; Nemergut et al., 2014) and that microbial functional redundancy alone is not enough to sustain ecosystem functioning in the face of degraded diversity.

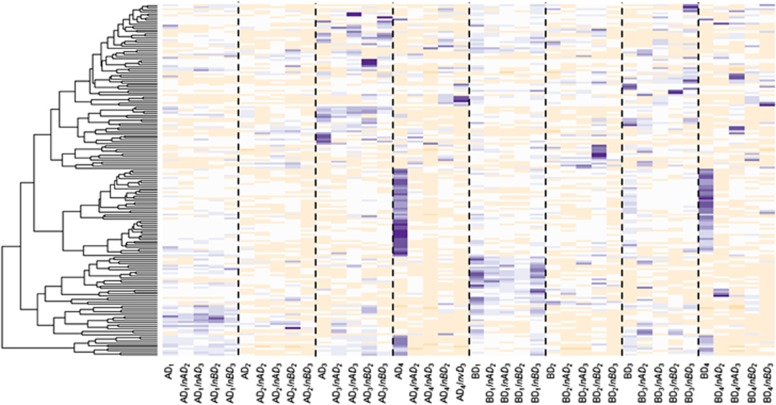

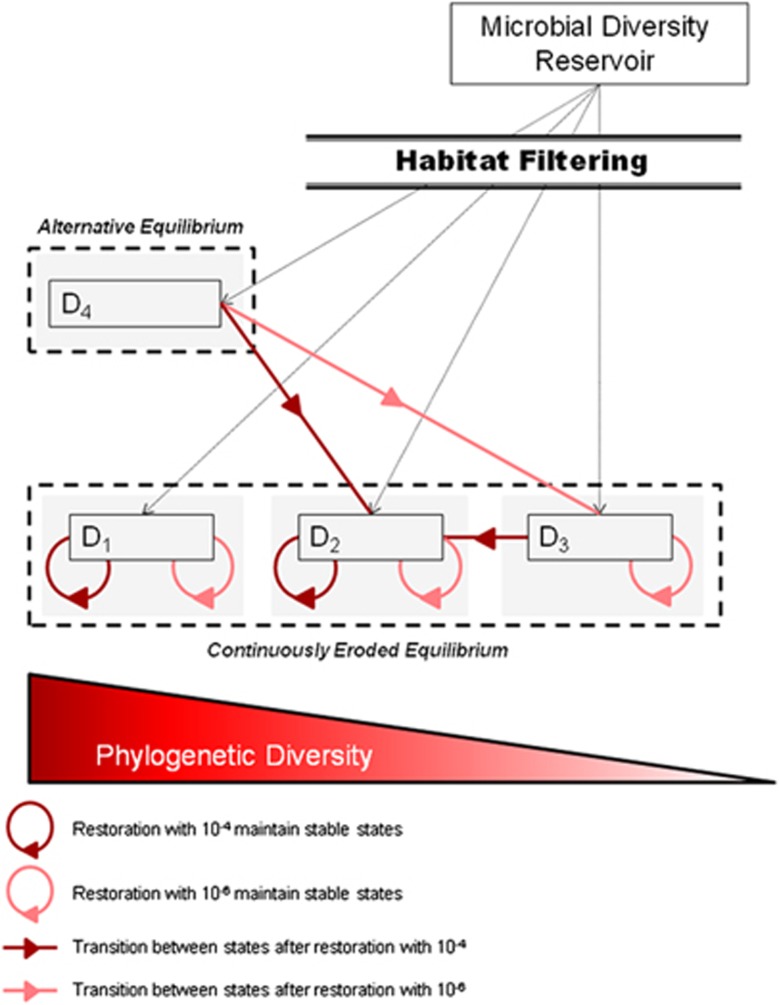

Rescue of soil biodiversity and functioning was attempted in the experimentally altered communities after 45 days, by reinoculating diluted suspensions (10−4 or 10−6) of the microbial communities from soils A or B using a reciprocal transplant design (Figure 1). The structure of the already-established D1 and D2 communities remained largely unchanged after re-inoculation, whatever the soil origin or dilution level (Figure 5, Supplementary Table S2). Indeed, the majority of the OTUs were shared between control and restored microcosms (Supplementary Figures S7 and S8), suggesting that colonization by the newly added species was restricted to a small fraction of available niche space, possibly owing to a low amount of available resources or intense competition with resident species (Nemergut et al., 2013). The analysis of the relative proportion of the different phyla/classes indicates that whatever the soil origin of the already-established D1 and D2 communities, re-inoculation by the community from soil B had a stronger effect than re-inoculation by the community from soil A (Figures 4b and c). These results illustrate the importance of historical contingency and priority effects in the dynamics of microbial communities (Fukami, 2015), that is, how the order in which species (or groups of species) colonize a substrate influences the assembly of communities (Chase, 2003), as previously revealed in simplistic experimental communities (Tan et al., 2012). Nevertheless, both Faith's PD and Simpson's reciprocal index along with species richness in D3 microcosms increased significantly after re-inoculation with the less-diluted soil suspensions (Figure 5b, Supplementary Table S2). Thus, between 354 and 467 new OTUs successfully established in the D3 microcosms after restoration (Supplementary Figures S7 and S8). This was concomitant with a shift toward a D2-type structure of communities (Figure 5a). The degraded community compositional state reached in D4 microcosms showed the poorest resistance to colonization by the newly added communities (Figures 5 and 6). Microbial community structure in D4 was more similar to those of D2- or D3-type communities after they had been re-inoculated with 10−4 or 10−6 soil suspensions, respectively, whereas the control D4 microcosms remained largely unchanged (Figures 2a and 5a). This was mirrored by the loss of 417 to 587 OTUs after addition of the 10−4 or 10−6 diluted soil suspensions, compared with the control D4 microcosms (Supplementary Figures S7 and S8). Strong differences were also observed on the heatmap of the 173 most abundant OTUs, with the replacement of OTUs that were found only in the D4 microcosms (Figure 6). As a result, in spite of supposedly greater diversity after the addition of new microbial communities, significantly lower diversity was observed in D4, with phylogenetic diversity dropping to the levels found in D2 or D3 microcosms (Tukey's HSD test, P<0.05; Figure 5b). We also found a stronger decrease of species richness in D4 after adding the 10−6 then after adding the 10−4 diluted soil suspensions, which indicates that introduction of a smaller number of species can have a stronger detrimental effect (Supplementary Table S2). A significant increase in bacterial abundance was observed in the restored D4 microcosms compared with the D4 control microcosms (Supplementary Figure S3). Altogether, these findings indicate that the newly introduced microbial species in D4 microcosms have not only filled the niche left vacant by the pioneering colonizers, but also have outcompeted many of them. This is consistent with resource-based niche theory linking the establishment of potential invaders to local resource availabilities and the features of resident species (Tilman, 2004). Adding species to the alternative D4-specific degraded state deeply changed its compositional structure and resulted in a lower diversity, demonstrating the instability of this alternative equilibrium to increased biodiversity and identifying it as a repellor state (Suding et al., 2004) (Figure 7). In experiments reported so far, only single or a few species were inoculated to assess the fate of beneficial or pathogenic microorganisms in soil (Jiang et al., 2010; Van Elsas et al., 2012). Our results obtained by re-introducing species-rich communities show that the establishment of newly introduced microbial communities is dependent on the diversity of the established ones but that priority effects could be overridden in restoration attempts. Given that the outcome of the restoration attempt was not random and depended on both microbial composition and diversity, our results suggest that it could be possible to optimize the establishment of introduced microorganisms based on the species present in the native and inoculated communities. In practice, this could be achieved by adding materials such as compost, manure or biochar carrying the microbial communities mostly likely to establish. This is consistent with a novel view of community interchange events or ‘community coalescence', which could permit targeted manipulation of microbial assemblages for application in restoration ecology but also in sustainable agriculture, medicine or industry (Rillig et al., 2015).

Figure 5.

Bacterial community structure and diversity in control and restored microcosms. (a) Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) of the unweighted UniFrac distance matrix representing differences in community structure at four dilution levels of control and restored microcosms at day 105. D1, D2, D3 and D4 dilutions from control microcosms are represented by red, green, blue and pink plain circles respectively. Restored microcosms D1, D2, D3 and D4 are represented by orange, light green, light blue and violet plain circles respectively. Owing to a limited effect of soil origin, the A and B soil communities have not been distinguished to simplify the figure. For each dilution, the control microcosms have been joined by a colored line. (b) Phylogenetic Diversity levels of control and restored communities at four dilution levels. Means±s.e.m are represented. The gray-shaded areas correspond to the interval between the control mean−s.e.m. and the control mean+s.e.m for each treatment. Samples are labeled according to the following scheme: AD1InAD2 stands for Dilution 1 from soil A inoculated with Dilution 2 from soil A.

Figure 6.

Heatmap of the relative abundances of the 173 most abundant OTUs in control and restored microcosms after 105 days incubation. Colors range from white (absence) to beige (low abundance) and dark blue (high abundance). OTUs were clustered based on their relative abundance profiles across treatments. Samples are labeled according to the following scheme: AD1InAD2 stands for Dilution 1 from soil A re-inoculated with Dilution 2 from soil A.

Figure 7.

Box and arrow representation of the state and transition model describing changes in the diversity and structure of microbial communities before and after restoration.

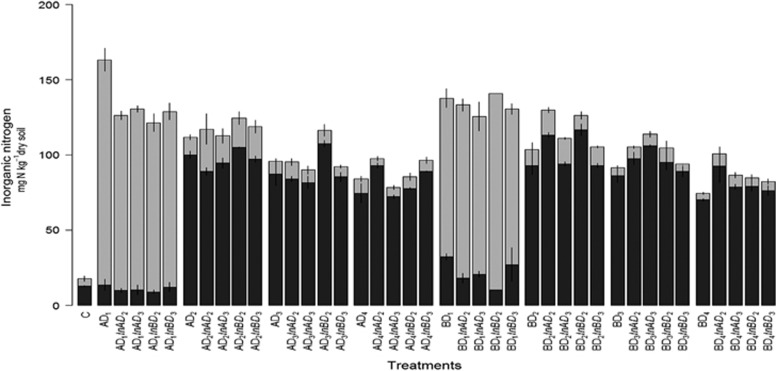

The analysis of soil mineral nitrogen pool sizes revealed only slight differences related to the addition of new microbial communities. Thus, NO3− pool size was still low in D2, D3 and D4 microcosms despite re-inoculation. This is consistent with the drastically different structure between D1 communities, in which nitrification occurred, and the D2, D3 and D4 restored communities. Ammonium pool sizes showed no clear trend despite significantly increased pool sizes in some microcosms after species addition, suggesting improved effectiveness of mineralization (Figure 8). This is further supported by the interaction between community diversity level and structure accounting for 36% of observed differences in N pools. Our work highlights the limits of ecological rescue of communities by exerting leverage on community assembly processes for impaired soil functions such as N cycling.

Figure 8.

Soil mineral nitrogen pool sizes in control and restored communities. Samples are labeled according to the following scheme: AD1InAD2 stands for microcosms established with Dilution 1 from soil A and inoculated with Dilution 2 from soil A. Dark gray indicates the NH4+ pool and light gray the NO3− pool. Means±s.d. of data are plotted.

The community-wide restoration approach evaluated in this study showed that attempting to rescue degraded soil biodiversity by adding complex microbial communities strongly depends on the nature and strength of species interactions. Ecological restoration even leads to an overall decrease in phylogenetic diversity and richness in systems that were in an alternative equilibrium state. However, we also demonstrated that priority effects could be overridden if the right combination of competitive species is provided, allowing community resilience toward a stable equilibrium. More generally, our results indicate that processes affecting the assemblage of microbial communities are mostly deterministic. A better understanding of these processes would therefore open the way for targeted microbial assemblages in the perspective of the restoration of the biological properties of degraded terrestrial ecosystems.

Acknowledgments

The sequences of genes reported in this paper are available at NCBI SRA under the accession number SRP057201. This research was supported by the European Commission within the EcoFINDERS project (FP7-264465) and the Conseil Régional de Bourgogne. In memory of Diana Nemergut.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on The ISME Journal website (http://www.nature.com/ismej)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bardgett RD, van der Putten WH. (2014). Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 515: 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D, Ben Mahfoudh K, Wagner M, Loy A. (2011). Barcoded primers used in multiplex amplicon pyrosequencing bias amplification. Appl Environ Microbiol 77: 7846–7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonebakker RG, Liaw WHA, Lumley T, Maechler M, Magnusson A, Moeller S et al. (2012). R package 'gplots' version 3.0.1.

- Bru D, Ramette A, Saby NP, Dequiedt S, Ranjard L, Jolivet C et al. (2011). Determinants of the distribution of nitrogen-cycling microbial communities at the landscape scale. Isme J 5: 532–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R. (2010. a). PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics 26: 266–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK et al. (2010. b). QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7: 335–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase JM. (2003). Community assembly: when should history matter? Oecologia 136: 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Community. (2006). Proposal for a directive of the European parliament and of the council establishing a framework for the protection of soil and amending directive.

- Csardi G, Nepusz T. (2006). The igraph software package for complex network research. Int J Complex Syst 1695: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Delmont TO, Francioli D, Jacquesson S, Laoudi S, Mathieu A, Nesme J et al. (2014). Microbial community development and unseen diversity recovery in inoculated sterile soil. Biol Fertil Soils 50: 1069–1076. [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. (2010). Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26: 2460–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith DP. (1992). Conservation evaluation and phylogenetic diversity. Biol Conserv 61: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Falkowski PG, Fenchel T, Delong EF. (2008). The microbial engines that drive Earth's biogeochemical cycles. Science 320: 1034–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J, Weisberg S. (2011). An {R} Companion to Applied Regression, Second Edition. Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA. Available from http://socserv.socsci.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion.

- Fukami T. (2015). Historical contingency in community assembly: Integrating niches, species pools and priority effects. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 46: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths BS, Ritz K, Wheatley R, Kuan HL, Boag B, Christensen S et al. (2001). An examination of the biodiversity-ecosystem function relationship in arable soil microbial communities. Soil Biol Biochem 33: 1713–1722. [Google Scholar]

- Harris J. (2009). Soil microbial communities and restoration ecology: facilitators or followers? Science 325: 573–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneghan L, Miller SP, Baer S, Callaham MA Jr, Montgomery J, Pavao-Zuckerman M et al. (2008). Integrating soil ecological knowledge into restoration management. Restor Ecol 16: 608–617. [Google Scholar]

- Henry S, Baudoin E, Lopez-Gutierrez JC, Martin-Laurent F, Brauman A, Philippot L. (2004). Quantification of denitrifying bacteria in soils by nirK gene targeted real-time PCR. J Microbiol Methods 59: 327–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry S, Bru D, Stres B, Hallet S, Philippot L. (2006). Quantitative detection of the nosZ gene, encoding nitrous oxide reductase, and comparison of the abundances of 16S rRNA, narG, nirK, and nosZ genes in soils. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 5181–5189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isbell F, Tilman D, Polasky S, Binder S, Hawthorne P. (2013). Low biodiversity state persists two decades after cessation of nutrient enrichment. Ecol Lett 16: 454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Tan J, Pu Z. (2010). An experimental test of Darwin's naturalization hypothesis. Am Nat 175: 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardol P, Van der Wal A, Martijn Bezemer T, de Boer W, Duyts H, Holtkamp R et al. (2008). Restoration of species-rich grasslands on ex-arable land: Seed addition outweighs soil fertility reduction. Biol Conserv 141: 2208–2217. [Google Scholar]

- Kardol P, Wardle DA. (2010). How understanding aboveground-belowground linkages can assist restoration ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 25: 670–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaus B, Strimmer K, Strimmer MK. (2014). R package 'fdrtool' version 1.2.15.

- Laughlin DC. (2014). Applying trait-based models to achieve functional targets for theory-driven ecological restoration. Ecol Lett 17: 771–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P, De Caceres M. (2013). Beta diversity as the variance of community data: dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol Lett 16: 951–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leininger S, Urich T, Schloter M, Schwark L, Qi J, Nicol GW et al. (2006). Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature 442: 806–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozupone C, Knight R. (2005). UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 71: 8228–8235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martorell C, Freckleton RP. (2014). Testing the roles of competition, facilitation and stochasticity on community structure in a species-rich assemblage. J Ecol 102: 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Mateos D, Power ME, Comin FA, Yockteng R. (2012). Structural and functional loss in restored wetland ecosystems. PLoS Biol 10: e1001247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer G, de Waal EC, Uitterlinden AG. (1993). Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 59: 695–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemergut DR, Schmidt SK, Fukami T, O'Neill SP, Bilinski TM, Stanish LF et al. (2013). Patterns and processes of microbial community assembly. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 77: 342–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemergut DR, Shade A, Violle C. (2014). When, where and how does microbial community composition matter? Front Microbiol 5: 497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwirth E. (2011). RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer palettes. R package version: 1.0-5.

- Ochsenreiter T, Selezi D, Quaiser A, Bonch-Osmolovskaya L, Schleper C. (2003). Diversity and abundance of Crenarchaeota in terrestrial habitats studied by 16S RNA surveys and real time PCR. Environ Microbiol 5: 787–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, Minchin PR, O'Hara R et al. (2013). vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.0-3. 2012.

- Peter H, Beier S, Bertilsson S, Lindstrom ES, Langenheder S, Tranvik LJ. (2011). Function-specific response to depletion of microbial diversity. Isme J 5: 351–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petric I, Philippot L, Abbate C, Bispo A, Chesnot T, Hallin S et al. (2011). Inter-laboratory evaluation of the ISO standard 11063 ‘Soil quality—Method to directly extract DNA from soil samples'. J Microbiol Methods 84: 454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippot L, Spor A, Henault C, Bru D, Bizouard F, Jones CM et al. (2013). Loss in microbial diversity affects nitrogen cycling in soil. Isme J 7: 1609–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. (2009). FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 26: 1641–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requena N, Perez-Solis E, Azcon-Aguilar C, Jeffries P, Barea JM. (2001). Management of indigenous plant-microbe symbioses aids restoration of desertified ecosystems. Appl Environ Microbiol 67: 495–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rillig MC, Antonovics J, Caruso T, Lehmann A, Powell JR, Veresoglou SD et al. (2015). Interchange of entire communities: microbial community coalescence. Trends Ecol Evol 30: 470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockstrom J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson A, Chapin FS 3rd, Lambin EF et al. (2009). A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 461: 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimel JP, Schaeffer SM. (2012). Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Front Microbiol 3: 348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB et al. (2009). Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol 75: 7537–7541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, Robert V, Spouge JL, Levesque CA et al. (2012). Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 6241–6246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MR, Charvat I, Jacobson RL. (1998). Arbuscular mycorrhizae promote establishment of prairie species in a tallgrass prairie restoration. Can J Bot 76: 1947–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RS, Shiel RS, Bardgett RD, Millward D, Corkhill P, Rolph G et al. (2003). Soil microbial community, fertility, vegetation and diversity as targets in the restoration management of a meadow grassland. J Appl Ecol 40: 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stone EA, Ayroles JF. (2009). Modulated modularity clustering as an exploratory tool for functional genomic inference. PLoS Genet 5: e1000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suding KN, Gross KL, Houseman GR. (2004). Alternative states and positive feedbacks in restoration ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 19: 46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J, Pu Z, Ryberg WA, Jiang L. (2012). Species phylogenetic relatedness, priority effects and ecosystem functioning. Ecology 93: 1164–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R, Hastie T, Narasimhan B, Chu G. (2002). Diagnosis of multiple cancer types by shrunken centroids of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 6567–6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilman D. (2004). Niche tradeoffs, neutrality, and community structure: a stochastic theory of resource competition, invasion, and community assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10854–10861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourna M, Freitag TE, Nicol GW, Prosser JI. (2008). Growth, activity and temperature responses of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms. Environ Microbiol 10: 1357–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Elsas JD, Chiurazzi M, Mallon CA, Elhottova D, Kristufek V, Salles JF. (2012). Microbial diversity determines the invasion of soil by a bacterial pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 1159–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vannette RL, Fukami T. (2014). Historical contingency in species interactions: towards niche-based predictions. Ecol Lett 17: 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagg C, Bender SF, Widmer F, van der Heijden MG. (2014). Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 5266–5270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young TP, Petersen DA, Clary JJ. (2005). The ecology of restoration: historical links, emerging issues and unexplored realms. Ecol Lett 8: 662–673. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.