Abstract

Objective

Recent randomized controlled trials have shown that age significantly affects the outcome of carotid revascularization procedures. This study used data from the Society for Vascular Surgery Vascular Registry (VR) to report the influence of age on the comparative effectiveness of carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and carotid artery stenting (CAS).

Methods

VR collects provider-reported data on patients using a Web-based database. Patients were stratified by age and symptoms. The primary end point was the composite outcome of death, stroke, or myocardial infarction (MI) at 30 days.

Results

As of December 7, 2010, there were 1347 CEA and 861 CAS patients aged <65 years and 4169 CEA and 2536 CAS patients aged ≥65 years. CAS patients in both age groups were more likely to have a disease etiology of radiation or restenosis, be symptomatic, and have more cardiac comorbidities. In patients aged <65 years, the primary end point (5.23% CAS vs 3.56% CEA; P = .065) did not reach statistical significance. Subgroup analyses showed that CAS had a higher combined death/stroke/MI rate (4.44% vs 2.10%; P < .031) in asymptomatic patients but there was no difference in the symptomatic (6.00% vs 5.47%; P = .79) group. In patients aged ≥65 years, CEA had lower rates of death (0.91% vs 1.97%; P < .01), stroke (2.52% vs 4.89%; P < .01), and composite death/stroke/MI (4.27% vs 7.14%; P < .01). CEA in patients aged ≥65 years was associated with lower rates of the primary end point in symptomatic (5.27% vs 9.52%; P < .01) and asymptomatic (3.31% vs 5.27%; P < .01) subgroups. After risk adjustment, CAS patients aged ≥65 years were more likely to reach the primary end point.

Conclusions

Compared with CEA, CAS resulted in inferior 30-day outcomes in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients aged ≥65 years. These findings do not support the widespread use of CAS in patients aged ≥65 years.

Stroke is the third leading cause of death and the leading cause of serious long-term disability in the United States.1,2 Several landmark randomized clinical trials since the 1990s have demonstrated the benefits of carotid end-arterectomy (CEA) compared with medical therapy in subgroups of patients with carotid artery occlusive disease.3–6 To date, many still consider CEA to be the “gold standard” for carotid revascularization procedures.

Since its introduction almost 2 decades ago, carotid angioplasty and stenting (CAS) has been touted as an alternative in patients at high risk for surgery.7,8 However, the efficacy of CAS compared with CEA remains unclear.9,10 Furthermore, increasing age has been shown to have a negative effect on the outcomes of CAS.10–14 The potential benefit of CAS in patients of increasing age therefore remains unclear.

The Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS) Vascular Registry (VR) on carotid procedures was developed to collect long-term outcomes for patients treated with CEA and CAS.15 As the first societal registry to enroll CEA and CAS patients, the SVS-VR is one of the largest published databases of carotid revascularization procedures in the United States. This study used the SVS-VR to evaluate the age-stratified comparative effectiveness of CEA and CAS. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) will likely revisit the National Coverage Decision (NCD) on CAS in the near future; therefore, we used 65 years as the cutoff because this is the age for Medicare eligibility.

METHODS

SVS-VR data are reported by providers through Web-based electronic data capture. The measurement schedule includes baseline preoperative information, such as patient demographics, medical history, carotid symptom status, preprocedural diagnostic imaging, laboratory results, and procedural information, including clinical utility, procedural and predischarge complications, as well as follow-up information such as postprocedural death, stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), and other morbidity.

All data entered into the VR are fully compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations and are auditable. All data reports and analyses performed included only deidentified and aggregated data. Additional details regarding the SVS-VR have been previously discussed.15 New England Research Institutes Inc (NERI, Watertown, Mass) maintains the online database. Funding for the administration and database management of the VR has been provided by the SVS (Chicago, Ill).

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure is a composite of the incidence of death, stroke, or MI. Stroke is defined as any nonconvulsive, focal neurologic deficit of abrupt onset persisting >24 hours. The ischemic event must correspond to a vascular territory. An MI is classified as either a Q wave MI in which one of the following criteria is required: (1) chest pain or other acute symptoms consistent with myocardial ischemia and new pathologic Q waves in two or more contiguous electrocardiogram (ECG) leads; or (2) new pathologic Q waves in two or more contiguous ECG leads and elevation of cardiac enzymes; or non-Q wave MI, which is defined as a creatine kinase (CK) ratio >2 and CK-MB >1 in the absence of new, pathologic Q waves. Analysis of the 30-day outcomes was based on only those patients who had at least a 30-day follow-up visit (>16 days) or who experienced an end point (death, stroke, or MI) ≥30 days of treatment.

Statistical methods

Tests of statistical significance were conducted with χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categoric variables and analysis of variance for continuous variables. Descriptive statistics are listed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and percentage (frequency) for categoric variables. Subset analyses were performed using the two-tailed t-test for continuous variables and the χ2 or Fisher exact test, as necessary, for discrete and categoric data. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (OR) were used to compare the primary outcomes across treatment groups and are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The ORs were adjusted for any significant baseline factors using logistic regression model. Differences were considered significant at P < .05. All statistical analyses were performed by NERI using SAS software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

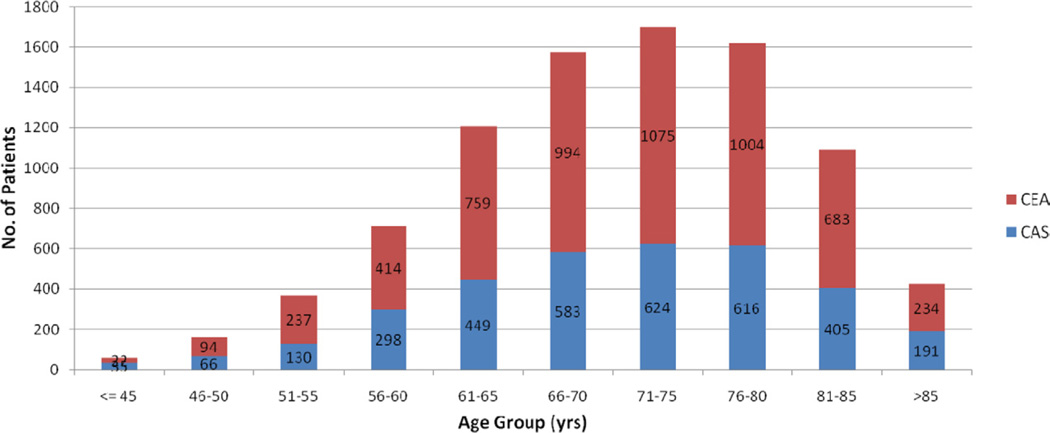

For the purpose of this report, data collected in the VR from the beginning of electronic data entry on July 11, 2005 to December 7, 2010 were analyzed. There were 8913 patients with 30-day follow-up data, of which 2208 (24.8%) were aged <65 and 6705 (75.2%) were aged ≥65 years. For those aged <65 years, 1347 (61.0%) underwent CEA and 861 (39.0%) had CAS. In patients aged ≥65 years, 4169 (62.2%) underwent CEA and 2536 (37.8%) had CAS. The age distribution of patients in this study can be found in the Fig.

Fig.

Age distribution and procedure for patients. CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy.

Patient characteristics can be found in Table I. In both age groups, patients undergoing CEA and CAS had similar sex and race distribution. However, the CAS subgroups had more patients with radiation (8.2% vs 0.1% [<65 years] and 3.8% vs 0.2% [≥65 years]) and restenosis (21.6% vs 0.8% [<65 years] and 24.5% vs 1.5% [≥65 years]) as the etiology of carotid artery disease. In those treated with CAS, the rate of symptomatic patients was higher (50.3% vs 43.4% [<65 years] and 43.9% vs 36.3% [≥65 years]). The CAS groups also had a higher prevalence of several medical comorbidities. The use of antiplatelet agents was more prevalent in CAS patients (95.9% vs 91.2% [<65 years] and 97.5% vs 89.3% [≥65 years]). The CAS groups also had a higher number of patients with baseline ultrasound-documented stenosis >80% (77.5% vs 71.1% [<65 years] and 76.8% vs 68.7% [≥65 years]) or contralateral stenosis >70% (30.9% vs 22.0% [<65 years] and 27.2% vs 18.7% [≥65 years]).

Table I.

Baseline demographics, disease etiology, medical history, and carotid evaluation

| Variablea | Patients<65 years |

Patients≥65 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA (n = 1347) |

CAS (n = 861) |

Pb | CEA (n = 4169) |

CAS (n = 2536) |

Pb | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, years | 58.3 (35–64) | 57.7 (18–28) | .0130 | 75.1 (65–98) | 75.4 (65–96) | .0557 |

| Male sex | 60.1 (809) | 59.3 (511) | .7401 | 58.3 (2429) | 59.9 (1520) | .1768 |

| White race | 89.7 (1208) | 88.7 (764) | .4825 | 93.6 (3901) | 93.4 (2368) | .7520 |

| Etiology | ||||||

| Atherosclerosis | 98.5 (1327) | 65.2 (561) | <.0001 | 98.0 (4086) | 70.3 (1784) | <.0001 |

| Dissection | 0.2 (3) | 2.4 (21) | 0.1 (4) | 0.3 (7) | ||

| Fibromuscular dysplasia | 0.1 (2) | 0.1 (1) | 0.1 (3) | 0.2 (4) | ||

| Radiation | 0.1 (1) | 8.2 (71) | 0.2 (7) | 3.8 (96) | ||

| Trauma | 0.1 (1) | 0.7 (6) | 0.0 (1) | 0.1 (2) | ||

| Restenosis | 0.8 (11) | 21.6 (186) | 1.5 (61) | 24.5 (621) | ||

| Other | 0.1 (2) | 1.7 (15) | 0.2 (7) | 0.9 (22) | ||

| Carotid symptoms | ||||||

| Symptomatic | 43.4 (585) | 50.3 (433) | .0016 | 36.3 (1513) | 43.9 (1114) | <.0001 |

| Medical history | ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 41.5 (559) | 51.6 (444) | <.0001 | 50.3 (2097) | 60.6 (1538) | <.0001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 16.1 (217) | 19.9 (171) | .0239 | 16.7 (697) | 23.8 (603) | <.0001 |

| Valvular heart disease | 4.8 (65) | 3.9 (34) | .3316 | 9.3 (386) | 7.3 (184) | .0043 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | 6.6 (89) | 7.8 (67) | .2936 | 14.9 (621) | 16.6 (421) | .0616 |

| Congestive heart failure | 6.0 (81) | 12.0 (103) | <.0001 | 8.5 (356) | 14.6 (371) | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | 80.9 (1090) | 79.2 (682) | .3248 | 85.0 (3542) | 83.8 (2125) | .2001 |

| Diabetes | 31.9 (430) | 36.4 (313) | .0316 | 31.4 (1311) | 32.4 (821) | .4291 |

| Transient ischemic attack | 20.2 (272) | 23.3 (201) | .0783 | 19.4 (807) | 24.5 (621) | <.0001 |

| Stroke | 22.0 (297) | 29.3 (252) | .0001 | 21.3 (890) | 24.6 (625) | .0017 |

| COPD | 16.9 (228) | 20.1 (173) | .0598 | 17.8 (742) | 19.6 (497) | .0656 |

| Chronic renal failure | 3.0 (40) | 2.7 (23) | .6814 | 3.6 (149) | 4.1 (105) | .2388 |

| Transient monocular blindness | 6.8 (91) | 10.3 (89) | .0027 | 4.9 (204) | 6.7 (171) | .0014 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 44.5 (600) | 36.7 (316) | .0003 | 46.0 (1916) | 37.8 (959) | <.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal ulcer/bleeding | 1.8 (24) | 2.6 (22) | .2146 | 3.1 (131) | 4.9 (124) | .0003 |

| Current or past smoker | 73.4 (989) | 69.2 (596) | .0324 | 55.8 (2326) | 57.4 (1456) | .1944 |

| Cancer | 6.2 (83) | 18.0 (155) | <.0001 | 15.3 (636) | 19.3 (490) | <.0001 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.3 (18) | 1.2 (10) | .7202 | 1.4 (60) | 1.1 (28) | .2423 |

| ASA grade ≤2 | 90.3 (1216) | 91.6 (789) | .2797 | 90.9 (3789) | 91.8 (2328) | .1999 |

| NYHA scale ≤3 | 95.5 (1287) | 88.3 (760) | <.0001 | 95.0 (3959) | 89.0 (2258) | <.0001 |

| Antiplatelet use | 91.2 (1229) | 95.9 (826) | <.0001 | 89.3 (3723) | 97.5 (2473) | <.0001 |

| Carotid evaluation | ||||||

| Baseline ultrasound >80% | 71.1 (887/1247) | 77.5 (538/694) | .0023 | 68.7 (2688/3912) | 76.8 (1708/2225) | <.0001 |

| Contralateral stenosis >70% | 22.0 (274/1243) | 30.9 (212/686) | <.0001 | 18.7 (728/3895) | 27.2 (600/2208) | <.0001 |

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CAS, carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Continuous variables are presented as mean (range); categoric variables as percentage (number).

P value for age was found using t-test. All others found using the Fisher exact test.

Patients aged <65 years

In patients aged <65 years (Table II), the difference in the primary outcome of composite death/stroke/MI (3.56% CEA vs 5.23% CAS; P = .0647) did not reach statistical significance. There were also no statistically significant differences in the individual end points of death, stroke, or MI. After risk adjustment for significant baseline factors, including etiology (atherosclerosis), presence of coronary artery disease, recent MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, stenosis >80%, and use of antiplatelet agents, gents, CEA was associated with a lower risk of MI (OR, 0.259; 95% CI, 0.068–0.985; P = .0474; Table III). After risk adjustment, there remained no statistically significant differences in the rates of death, stroke, or the combined primary end point in patients aged <65 years. In the symptomatic subgroup, there was no difference in the primary end point (5.47% CEA vs 6.00% CAS; P = .7848; Table IV). Although there was no difference in individual end points in the asymptomatic subgroup, the composite death/stroke/MI end point was lower for CEA (2.10% vs 4.44%; P = .0306). After risk adjustment, no differences remained in outcomes between symptomatic patients aged <65 years (Table V). The risk of MI approached statistical significance (OR, 0.189; 95% CI, 0.035–1.025; P = .0534) in asymptomatic patients, but there was no difference in the risk for the primary end point (OR, 0.501; 95% CI, 0.208–1.208; P = .1236; Table VI).

Table II.

Thirty-day outcomes for patients aged <65 years by procedurea

| 30-day events | Age < 65 years, % (n) |

Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAS (n = 861) |

CEA (n = 1347) |

||

| Mortality | 1.16 (10) | 0.74 (10) | .3594 |

| Stroke | 3.48 (30) | 2.82 (38) | .3797 |

| MI | 0.93 (8) | 0.30 (4) | .0716 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 5.23 (45) | 3.56 (48) | .0647 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; MI, myocardial infarction.

Outcomes were defined as occurring intraoperatively, before discharge, or between discharge and 30 days. Rates are per-patient.

P values were based on the Fisher exact test.

Table III.

Risk-adjusted odds ratios (OR) for patients <65 yearsa

| Event | CEA (vs CAS) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | Pb | OR | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Death | 0.636 | 0.264–1.536 | .3147 | 0.911 | 0.256–3.242 | .8852 |

| Stroke | 0.804 | 0.494–1.308 | .3798 | 0.681 | 0.379–1.225 | .1996 |

| MI | 0.318 | 0.095–1.058 | .0617 | 0.259 | 0.068–0.985 | .0474 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 0.670 | 0.442–1.015 | .0591 | 0.664 | 0.398–1.110 | .1185 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusted ORs calculated after adjusting for atherosclerosis, presence of coronary artery disease, recent MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, stenosis >80% on ultrasound, and use of antiplatelets agents.

P values were based on the χ2 test.

Table IV.

Thirty-day outcomes for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients <65 years by treatment arma

| 30-day events | Symptomatic, % (n) |

Asymptomatic, % (n) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA (n = 585) |

CAS (n = 443) |

Pb | CEA (n = 762) |

CAS (n = 428) |

Pb | |

| Death | 0.68 (4) | 0.92 (4) | .7290 | 0.79 (6) | 1.40 (6) | .3679 |

| Stroke | 4.79 (28) | 4.62 (20) | >.9999 | 1.31 (10) | 2.34 (10) | .2394 |

| MI | 0.17 (1) | 0.69 (3) | .3177 | 0.39 (3) | 1.17 (5) | .1447 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 5.47 (32) | 6.00 (26) | .7848 | 2.10 (16) | 4.44 (19) | .0306 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; MI, myocardial infarction.

Outcomes were defined as occurring intraoperatively, predischarge, or between discharge and 30 days. Rates are per-patient.

P values were based on the Fisher exact test.

Table V.

Risk-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for symptomatic patients aged <65 yearsa

| 30-day events | CEA (vs CAS) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | Pb | OR | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Death | 0.738 | 0.184–2.969 | .6692 | 2.389 | 0.275–20.759 | .4297 |

| Stroke | 1.038 | 0.577–1.868 | .9011 | 0.730 | 0.370–1.441 | .3642 |

| MI | 0.245 | 0.025–2.368 | .2245 | 0.309 | 0.026–3.686 | .3530 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 0.906 | 0.532–1.544 | .7161 | 0.811 | 0.429–1.532 | .5182 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusted ORs calculated after adjusting for atherosclerosis, presence of coronary artery disease, recent MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, stenosis >80% on ultrasound imaging, and use of antiplatelet agents.

P values were based on the χ2 test.

Table VI.

Risk-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for asymptomatic patients aged <65 yearsa

| 30-day events | CEA (vs CAS) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | Pb | OR | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Death | 0.558 | 0.179–1.742 | .3152 | 0.445 | 0.090–2.192 | .3194 |

| Stroke | 0.556 | 0.229–1.346 | .1932 | 0.695 | 0.206–2.339 | .5567 |

| MI | 0.334 | 0.080–1.406 | .1349 | 0.189 | 0.035–1.025 | .0534 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 0.462 | 0.235–0.908 | .0250 | 0.501 | 0.208–1.208 | .1236 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusted ORs calculated after adjusting for atherosclerosis, presence of coronary artery disease, recent MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, stenosis >80% on ultrasound imaging, and use of antiplatelet agents.

P values were based on the χ2 test.

Patients aged ≥65 years

Patients aged ≥65 years (Table VII) undergoing CEA had a lower incidence of death (0.91% vs 1.97%; P = .0003) and stroke (2.52% vs 4.89%; P < .0001). There was no difference in the rate of MI (1.39% CEA vs 1.30% CAS; P = .8280). Overall, the composite death/stroke/MI rate (4.27% vs 7.14%; P < .0001) was significantly lower in patients undergoing CEA. After risk adjustment, CEA remained associated with lower rates of death (OR, 0.592; 95% CI, 0.356–0.985; P = .0436), stroke (OR, 0.459; 95% CI, 0.335–0.628; P < .001), and composite death/stroke/MI (OR, 0.593; 95% CI, 0.459–0.765; P < .001) in patients aged >65 years (Table VIII).

Table VII.

Thirty-day outcomes for patients aged ≥65 years by procedurea

| 30-day events | Age ≥65 y ears, % (n) |

Pb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAS (n = 2536) |

CEA (n = 4169) |

||

| Death | 1.97 (50) | 0.91 (38) | .0003 |

| Stroke | 4.89 (124) | 2.52 (105) | <.0001 |

| MI | 1.30 (33) | 1.39 (58) | .8280 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 7.14 (181) | 4.27 (178) | <.0001 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; MI, myocardial infarction.

Outcomes were defined as occurring intraoperatively, predischarge, or between discharge and 30 days. Rates are per-patient.

P values were based on the Fisher exact test.

Table VIII.

Risk-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for patients aged ≥65 yearsa

| 30-day events | CEA (vs CAS) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | Pb | OR | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Death | 0.457 | 0.299–0.699 | .0003 | 0.592 | 0.356–0.985 | .0436 |

| Stroke | 0.503 | 0.386–0.655 | <.0001 | 0.459 | 0.335–0.628 | <.0001 |

| MI | 1.070 | 0.696–1.645 | .7576 | 1.086 | 0.648–1.819 | .7551 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 0.580 | 0.469–0.718 | <.0001 | 0.593 | 0.459–0.765 | <.0001 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence interval; MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusted ORs calculated after adjusting for atherosclerosis, presence of coronary artery disease, recent MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, stenosis >80% on ultrasound imaging, and use of antiplatelet agents.

P values were based on the χ2 test.

Subgroup analyses also demonstrated CEA was associated with lower rates of the primary end point in symptomatic (5.95% vs 9.52%; P= .0007) and asymptomatic (3.31% vs 5.27%; P = .0032) patients (Table IX). After risk adjustment, CEA continued to be associated with lower risks of stroke in symptomatic (OR, 0.475; 95% CI, 0.313–0.720; P = .0005) and asymptomatic (OR, 0.474; 95% CI, 0.292–0.767; P = .0024) patients (Tables X and XI). The risk of composite death/stroke/MI was also lower in symptomatic (OR, 0.475; 95% CI, 0.313–0.720; P = .0005) and asymptomatic (OR, 0.474; 95% CI, 0.292–0.767; P = .0024) patients.

Table IX.

Thirty-day outcomes for symptomatic and asymptomatic patients ≥65 years by treatment arma

| 30-day events | Symptomatic, % (n) |

Asymptomatic, % (n) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA (n=1513) |

CAS (n=1114) |

Pb | CEA (n=2656) |

CAS (n=1422) |

Pb | |

| Death | 1.26 (19) | 2.42 (27) | .0340 | 0.72 (19) | 1.62 (23) | .0087 |

| Stroke | 3.77 (57) | 6.73 (75) | .0008 | 1.81 (48) | 3.45 (49) | .0016 |

| MI | 1.72 (26) | 1.62 (18) | .8789 | 1.20 (32) | 1.05 (15) | .7591 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 5.95 (90) | 9.52 (106) | .0007 | 3.31 (88) | 5.27 (75) | .0032 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; MI, myocardial infarction.

Outcomes were defined as occurring intraoperatively, predischarge, or between discharge and 30 days. Rates are per-patient.

P values were based on the Fisher exact test.

Table X.

Risk-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for symptomatic patients ≥65 yearsa

| 30-day events | CEA (vs CAS) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | Pb | OR | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Death | 0.512 | 0.283–0.926 | .0267 | 0.660 | 0.320–1.363 | .2619 |

| Stroke | 0.542 | 0.381–0.772 | .0007 | 0.475 | 0.313–0.720 | .0005 |

| MI | 1.065 | 0.581–1.952 | .8395 | 0.992 | 0.485–2.031 | .9829 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 0.601 | 0.449–0.806 | .0007 | 0.585 | 0.413–0.830 | .0026 |

CAS, Ccarotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusted ORs calculated after adjusting for atherosclerosis, presence of coronary artery disease, recent MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, stenosis >80% on ultrasound imaging, and use of antiplatelet agents.

P values were based on the χ2 test.

Table XI.

Risk-adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for asymptomatic patients ≥65 yearsa

| 30-day events | CEA (vs CAS) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

|||||

| OR | 95% CI | Pb | OR | 95% CI | Pb | |

| Death | 0.438 | 0.238–0.807 | .0081 | 0.546 | 0.265–1.124 | .1005 |

| Stroke | 0.516 | 0.345–0.772 | .0013 | 0.474 | 0.292–0.767 | .0024 |

| MI | 1.144 | 0.617–2.119 | .6692 | 1.379 | 0.629–3.020 | .4224 |

| Death/stroke/MI | 0.615 | 0.449–0.843 | .0025 | 0.649 | 0.443–0.953 | .0273 |

CAS, Carotid artery stenting; CEA, carotid endarterectomy; CI, confidence intervals, MI, myocardial infarction.

Adjusted ORs calculated after adjusting for atherosclerosis, presence of coronary artery disease, recent MI, congestive heart failure, stroke, stenosis >80% on ultrasound imaging, and use of antiplatelet agents.

P values were based on the χ2 test.

DISCUSSION

Since its introduction in the 1990s, CAS has offered an alterative to CEA in the treatment of carotid artery stenosis. In March 2005, CMS approved coverage for CAS in symptomatic patients who were at high risk for CEA. Since that time, the comparative effectiveness of CEA and CAS continues to be debated despite the publication of results from two large randomized clinical trials.9,10 Furthermore, the influence of age on clinical outcomes remains unclear.

Although some small series have reported excellent results of CAS in octogenarians,16,17 most studies have demonstrated that advanced age is an independent predictor of in-hospital death and stroke after CAS. In the lead-in phase of the Carotid Revascularization Endarterectomy vs Stenting Trial (CREST), periprocedural events after CAS were significantly affected by patient age.11 The 30-day periprocedural stroke and death rate increased with age: 1.7% for patients aged <60, 1.3% for those 60 to 69, 5.3% for those aged 70 to 79, and 12.1% for those aged ≥80 years. Stanziale et al12 reported that octogenarians undergoing CAS had a higher rate of 30-day stroke, MI, or death (9.2% vs 3.4%) than nonoctogenarians.

In a study of 5297 patients from the Carotid ACCU-LINK/ACCUNET Post Approval Trial to Uncover Rare Events (CAPTURE 2) trial, combined death/stroke rates were significantly higher for octogenarians than for nonoctogenarians (4.5% vs 3.0%) as were stroke rates (3.8% vs 2.4%).13 CREST data comparing the effect of age on the outcomes of CAS vs CEA showed an interaction between age and treatment efficacy, with a crossover at an age of ~70 years; CAS tended to show greater efficacy at younger ages and CEA at older ages.10 In a pooled analysis of three trials (Endarterectomy Versus Angioplasty in Patients With Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis [EVA-3S], Stent-Supported Percutaneous Angioplasty of the Carotid Artery versus Endarterectomy [SPACE], and International Carotid Stenting Study [ICSS]) of patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis who could undergo surgery at standard risk, age was the only subgroup variable that significantly modified the treatment effect.14 In patients aged <70 years, the 120-day stroke or death risk was 5.8% in CAS and 5.7% in CEA; in patients aged ≥70 years, there was an estimated twofold increased risk with CAS vs CEA (12.0% vs 5.9%).

To understand why CAS in elderly patients is often associated with poorer outcomes, several factors need to be considered. Analyses of complications of CAS have highlighted the significant contribution of embolization originating from sources proximal to the treated lesion.18,19 Because neurologic events can occur in the contralateral hemisphere as well as before the internal carotid lesion is crossed, manipulation with wires, catheters, and sheaths in tortuous or diseased access vessels can contribute to the complications seen with CAS. Elderly patients are more likely to have heavily calcified aortic arches than younger patients20 and to have other unfavorable anatomic characteristics (such as arch elongation, common carotid or innominate stenosis, and tortuosity) that increase the technical difficulty of performing CAS.21 In addition to anatomic considerations, patients aged >70 years with significant carotid stenosis may have compromised intracranial collaterals and thus have poor cerebral reserve.22 Older patients may thus be more sensitive to minor cerebral emboli, which may contribute to a higher stroke risk during CAS.

Although the studies mentioned here have noted the varying outcomes in octogenarians as well as in those older and younger than 70, the age of 65 years was used in this study. With publication of CREST and ICSS, two large clinical trials of carotid revascularization, we concluded that CMS would likely revisit the NCD on CAS in the near future. As such, the patients in this study were subdivided into those who would and would not qualify for Medicare coverage by their age. Data from the SVS-VR were used to analyze 30-day outcomes for 8913 patients who underwent carotid revascularization procedures. In patients aged <65 years old, outcomes of CEA and CAS were comparable, with no statistically significant differences in the unadjusted rates of death, stroke, and MI. Although there remained no difference in the composite end point, patients aged <65 years undergoing CEA had a lower risk of MI (OR, 0.259; P = .0474) than those undergoing CAS.

This finding differs from the results of CREST, in which the incidence of periprocedural MI was lower in the stenting group.10 In this study, the rates of MI in CEA patients (0.30% in <65 and 1.39% in ≥65 years) were lower than those reported in all patients from CREST (2.3%) but were higher than the rate (0.4%) reported in the pooled European trials.10,14 In evaluating patients aged ≥65 years, CEA was associated with lower rates of death (0.91% vs 1.97%; P = .0003), stroke (2.52% vs 4.89%; P< .0001), and the primary composite end point of death/stroke/MI (4.27% vs 7.14%; P < .0001). After risk adjustment, CEA continued to be associated with lower risks of death (OR, 0.592; P = .0436), stroke (OR, 0.459; P < .0001), and death/stroke/MI (OR, 0.593; P < .0001). The outcomes of CAS in patients aged ≥65 years remained inferior to those with CEA when patients were divided into the symptomatic and asymptomatic subgroups.

The results in this study may differ slightly from those published in CREST because the data from the SVS-VR represent real-world outcomes. The SVS-VR is available to all clinical facilities and providers in the United States wishing to participate. As such, although the VR suffers from self-reporting bias, it includes a broad collection of institutions and physicians, thus possibly presenting data that coincide with results found in the real world.

In addition, CAS has a significant procedurally related learning curve, and numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of operator experience in the clinical success of CAS.23–26 Implanting physicians in CREST were certified only after a satisfactory evaluation of their experience, results, and participation in a lead-in phase of training.10 This type of credentialing and monitoring process certainly does not exist in routine practice on a national level. Studies of carotid revascularization have demonstrated different results in actual practice compared with those reported in clinical trials.

Outcome disparities have been shown in Medicare patients undergoing CEA, who had a much higher perioperative mortality rate than that reported in trials, even among institutions that participated in the randomized studies.27 A more recent study also showed that patients undergoing CAS who participated in company-sponsored postmarketing surveillance studies had less baseline neurologic disease and lower mortality rates compared with CAS patients who did not participate in the studies.28 As such, practice guidelines and policy changes may be more appropriately based on findings of comparative effectiveness seen in real-world settings as opposed to efficacy demonstrated in carefully controlled clinical trials.

Several limitations of this study warrant further discussion. The main limitation is that data from registries such as the SVS-VR are not designed to mimic clinical trials. Thus, not all clinical factors that result in treatment bias can be readily identified. Anatomic information (such as plaque characteristic, degree of vessel tortuosity, calcification) and other important factors (such as operator experience) were not available, and any confounding effects these factors may have on the study outcomes cannot be adequately analyzed.

There are also limitations specific to secondary data analyses of databases such as the SVS-VR. We must again note that data are self-reported by treating physicians and institutions. The potential effect of reporting bias within the SVS-VR has been investigated and discussed.7 Finally, as with all studies using registry data, the collected information is retrospective. However, data from independent and verifiable registries still can provide valuable information about clinical outcomes in the absence of randomized evidence.

CONCLUSIONS

The results from this multicenter observational study demonstrated that CAS was associated with higher rates of postoperative complications compared with CEA. Although CAS may be preferred over CEA in some situations because of certain medical risk factors or anatomic considerations, identification for this subset of patients was beyond the scope of this study. However, the current available evidence simply does not support the widespread use of CAS. Our analysis of data from a registry on carotid revascularization procedures found that patients aged ≥65 years old undergoing CAS had higher rates of death and stroke, and combined death/stroke/MI, than those undergoing CEA. The findings in this report do not support the widespread use of CAS in patients aged ≥65 years old.

Acknowledgments

The analysis of the SVS Vascular Registry carotid data set was supported exclusively by funds from the Society for Vascular Surgery (SVS).

APPENDIX.

SVS Outcomes Committee

Gregorio A. Sicard (Chair), Ellen D. Dillavou, Patrick J. Geraghty, Philip P. Goodney, Gregg S. Landis, Louis L. Nguyen, Joseph Ricotta, Marc L. Schermerhorn, Flora S. Siami (ad hoc), and Rodney A. White.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest: none.

The editors and reviewers of this article have no relevant financial relationships to disclose per the JVS policy that requires reviewers to decline review of any manuscript for which they may have a competition of interest.

Presented at the Thirty-sixth Annual Spring Meeting of the Peripheral Vascular Surgery Society, Chicago, Ill, June 15, 2011.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: JJ

Analysis and interpretation: JJ, CK, FS

Data collection: CK, FS

Writing the article: JJ, CK, FS

Critical revision of the article: JJ, BR, JR, CK, FS, GS

Final approval of the article: JJ, BR, JR, CK, FS, GS

Statistical analysis: CK, FS

Obtained funding: GS

Overall responsibility: JJ

REFERENCES

- 1.Heron MP, Hoyert DL, Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: final data for 2006. Natl Vital Statist Rep. 2009;57:1–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K. Heart disease stroke statistics-2009 updates A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:e1–e161. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) Investigators. Benefit of carotid endarterectomy for patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:445–453. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.European Carotid Surgery Trialist’s Collaborative Group. Randomized trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC, European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) Lancet. 1998;351:1379–1387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, et al. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1491–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16146-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks MP, Dake MD, Steinberg GK, Norbash AM, Lane B. Stent placement for artery and venous cerebrovascular disease: preliminary experience. Radiology. 1994;191:441–446. doi: 10.1148/radiology.191.2.8153318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yadav JS, Roubin GS, Iyer S, Vitek J, King P, Jordan WD, et al. Elective stenting of the extracranial carotid arteries. Circulation. 1997;95:376–381. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Carotid Stenting Study investigators. Ederle J, Dobson J, Featherstone RL, Bonati LH, van der Worp HB, et al. Carotid artery stenting compared with endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis (International Carotid Stenting Study): an interim analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:985–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brott TG, Hobson RW2nd, Howard G, Roubin GS, Clark WM, Brooks W, et al. CREST investigators. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:11–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hobson RW2nd, Howard VJ, Roubin GS, Brott TG, Ferguson RD, Popma JJ, et al. CREST investigators. Carotid artery stenting is associated with increased complications in octogenarians: 30-day stroke and death rates in the CREST lead-in phase. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40:1106–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanziale SF, Marone LK, Boules TN, Brimmeier JA, Hill K, Makaroun MS, et al. Carotid artery stenting in octogenarians is associated with increased adverse outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaturvedi S, Matsumura JS, Gray W, Xu C, Verta P CAPTURE 2 Investigators Executive Committee. Carotid artery stenting in octogenarians: periprocedural stroke risk predictor analysis from the multicenter Carotid ACCULINK/ACCUNET Post Approval Trial to Uncover Rare Events (CAPTURE 2) clinical trial. Stroke. 2010;41:757–764. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.569426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonati LH, Fraedrich G. Carotid Stenting Trialists’ Collaboration. Age modifies the relative risk of stenting versus endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis-a pooled analysis of EVA-3S, SPACE and ICSS. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2011;41:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sidawy AN, Zwolak RM, White RA, Siami FS, Schermerhorn ML, Sicard GA, et al. Risk-adjusted 30-day outcomes of carotid stenting and endarterectomy: results from the SVS vascular registry. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo GM, Kibbe MR, Eskandari MK. Carotid artery stenting in octogenarians: is it too risky? Ann Vasc Surg. 2005;19:812–816. doi: 10.1007/s10016-005-7977-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bacharach JM, Slovut DP, Ricotta J, Sullivan TM. Octogenarians are not at increased risk for periprocedural stroke following carotid artery stenting. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammer FD, Lacroix V, Duprez T, Grandin C, Verhelst R, Peeters A, et al. Cerebral microembolization after protected carotid artery stenting in surgical high-risk patients: results of a 2-year prospective study. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fairman R, Gray WA, Scicli AP, Wilburn O, Verta P, Atkinson R, et al. for the CAPTURETrial Collaborators. The CAPTURE registry: analysis of strokes resulting from carotid artery stenting in the post approval setting: timing, location, severity, and type. Ann Surg. 2007;246:551–556. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181567a39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bazan HA, Pradhan S, Mojibian H, Kyriakides T, Dardik A. Increased aortic arch calcification in patients older than 75 years: implications for carotid artery stenting in elderly patients. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:841–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam RC, Lin SC, DeRubertis B, Hynecek R, Kent KC, Faries PL. The impact of increasing age on anatomic factors affecting carotid angio-plasty and stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:875–880. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaer RA, Shen J, Rao A, Cho JS, Abu Hamad G, Makaroun MS. Cerebral reserve is decreased in elderly patients with carotid stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:569–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmadi R, Willfort A, Lang W, Schillinger M, Alt E, Gschwandtner ME, et al. Carotid artery stenting: effect of learning curve and intermediate-term morphological outcome. J Endovasc Ther. 2001;8:539–546. doi: 10.1177/152660280100800601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin PH, Bush RL, Peden E, Zhou W, Kougias P, Henao E, et al. What is the learning curve for carotid artery stenting with neuroprotection? Analysis of 200 consecutive cases at an academic institution. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2005;17:113–125. doi: 10.1177/153100350501700211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verzini F, Cao P, De Rango P, Parlani G, Maselli A, Romano L, et al. Appropriateness of learning curve for carotid artery stenting: an analysis of periprocedural complications. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44:1205–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gray WA, Rosenfield KA, Jaff MR, Chaturvedi S, Peng L, Verta P CAPTURE2 Investigators and Executive Committee. Influence of site and operator characteristics on carotid artery stent outcomes: analysis of the CAPTURE 2 (Carotid ACCULINK/ACCUNET Post Approval Trial to Uncover Rare Events) clinical study. JACC Cardiovasc Intv. 2011;4:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wennberg DE, Lucas FL, Birkmeyer JD, Bredenberg CE, Fisher ES. Variation in carotid endarterectomy mortality in the Medicare population: trial hospitals, volume, and patient characteristics. JAMA. 1998;279:1278–1281. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.16.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeh RW, Kennedy K, Spertus JA, Parikh SA, Sakhuja R, Anderson HV, et al. Do postmarketing surveillance studies represent real-world populations? A comparison of patient characteristics and outcomes after carotid artery stenting. Circulation. 2011;123:1384–1390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.991075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]