Abstract

Background

Hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy causes an acute increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR). The increase in PVR and right ventricular (RV) afterload leads to acute RV failure, thus reducing left ventricular (LV) preload and output. iNO lowers PVR by relaxing pulmonary arterial smooth muscle without remarkable systemic vascular effects. We hypothesized that with hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy, iNO can be used to decrease PVR and mitigate right heart failure.

Methods

A hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy model was developed using sheep. Sheep received lung protective ventilatory support and were instrumented to serially obtain measurements of hemodynamics, gas exchange and blood chemistry. Heart function was assessed with echocardiography. After randomization to study gas of iNO 20 ppm (n = 9) or nitrogen as placebo (n = 9), baseline measurements were obtained. Hemorrhagic shock was initiated by exsanguination to a target of 50% of the baseline mean arterial pressure. The resuscitation phase was initiated, consisting of simultaneous left pulmonary hilum ligation, via median sternotomy, infusion of autologous blood and initiation of study gas. Animals were monitored for 4 hours.

Results

All animals had an initial increase in PVR. PVR remained elevated with placebo; with iNO, PVR decreased to baseline. Echo showed improved RV function in the iNO group while it remained impaired in the placebo group. After an initial increase in shunt and lactate and decrease in SvO2, all returned towards baseline in the iNO group but remained abnormal in the placebo group.

Conclusion

These data indicate that by decreasing PVR, iNO decreased RV afterload, preserved RV and LV function, and tissue oxygenation in this hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy model. This suggests that iNO may be a useful clinical adjunct to mitigate right heart failure and improve survival when trauma pneumonectomy is required.

Keywords: Inhaled nitric oxide, hemorrhage, pneumonectomy, pulmonary vascular resistance, cardiac function

Background

While pneumonectomy in the setting of trauma is a rare occurrence, in the presence of pulmonary hilar vascular or extensive main stem bronchial injury, pneumonectomy may be the only option. Of the few case series in the literature demonstrating outcomes of these patients, mortality associated with trauma pneumonectomy has been reported to range from 50-100%1-4. Moreover, when pneumonectomy is performed on the background of hemorrhagic shock, the mortality rate is even higher than the mortality rate for pneumonectomy in the setting of isolated bronchial injury1. Overall, the high mortality rates have been attributed to right heart failure1-4.

Right heart failure following combined hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy occurs secondary to an acute increase in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR)2, 4. In animal studies, the increase in PVR seen in pneumonectomy and hemorrhagic shock models has been shown to be greater than the additive effects of each of these situations on their own and irreversible4. Additionally, pneumonectomy and resuscitation have the potential to cause acute lung injury2. This can lead to alveolar hypoxia, a major contributor to pulmonary vasoconstriction and increase in PVR2. Ultimately, these risk factors lead to an increase in right ventricular (RV) afterload and a dysfunctional scenario of which compensatory mechanisms are exceeded, resulting in RV failure, decreased cardiac index, systemic hypoperfusion, tissue hypoxia and death. An effective mechanism for mitigating this problem would include a treatment focused at the source of the increase in PVR, specifically, selective vasodilation of the pulmonary vasculature.

Inhaled nitric oxide (iNO) has been shown to be a selective vasodilator of pulmonary vascular smooth muscle, with minimal or no hemodynamic systemic effects5, 6. The reduction in pulmonary vascular tone and consequently PVR leads to decreased pulmonary arterial pressure and ultimately decreased RV afterload, which mechanistically decreases the workload of the right ventricle and has the potential to prevent right heart failure6. These beneficial properties of iNO have been used to induce vasodilation in primary pulmonary hypertension, ARDS and secondary pulmonary hypertension due to congenital heart disease7. In a non-randomized study of patients with acute right heart failure, iNO was shown to increase cardiac output, stroke volume and mixed venous oxygen saturation, thereby improving hemodynamic parameters, and while not directly measured, has been related to improving RV dysfunction5.

While sparse, the few case studies of the use of iNO in hemorrhagic shock patients requiring trauma pneumonectomy have reported improved cardiac output, reduced pulmonary artery pressures and ultimately improved survival7, 8. However, the impact of iNO to mitigate right heart failure in the presence of hemorrhagic shock and trauma pneumonectomy has not been systematically or directly studied. With this in mind, the purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that iNO could be used to decrease PVR, unload the right ventricle, and attenuate alterations in right heart function, thereby reduce right heart failure in an animal model of hemorrhagic shock and trauma pneumonectomy.

Methods

All methods were approved by the Temple University animal care and use committee in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Animal Preparation: Sheep (n = 19; weight: 23.7 ± 0.71 kg) were anesthetized with intramuscular (IM) injections of buprenorphine hydrochloride (0.005 mg/kg) and ketamine/xylazine (20/2mg/kg), restrained in the supine position, intubated (8.0 mm), immediately instrumented with electrocardiogram leads, pulse oximetry, and an orogastic tube, and placed on lung protective ventilatory support (Servo 300; Siemens, Solna, Sweden) initiated with pressure-controlled (peak inspiratory pressure [PIP] = 18 cmH20, positive end expiratory pressure [PEEP]= 8 cmH2O), synchronized intermittent mechanical ventilation at a rate of 12 br/min with heated and humidified FIO2 (0.40 – 0.60) titrated to SpO2 target of > 90%. Bilateral peripheral leg veins were isolated and cannulated for administration of anesthesia (guaifenesin/ketamine/xylazine at 50/2/0.1 mg/ml; 0.25-2.5 ml/kg/hr), maintenance fluids, and autologous blood. The right carotid artery was cannulated (8 Fr) for continuous blood pressure monitoring and serial sampling of arterial blood chemistry. The left femoral artery (8 Fr) and internal jugular vein (16 Fr) were cannulated for blood withdrawal. The right external jugular vein was cannulated with a thermodilution catheter (7.5 Fr) that was advanced into the pulmonary artery under transduced pressure guidance for continuous monitoring of pulmonary pressures and serial measurement of mixed venous blood chemistry and cardiac output. All sheep were placed on a temperature controlled water-circulating pad and under a warming blanket for temperature support as continuously measured by rectal probe.

Following baseline measurements (blood pressure, heart rate, pulmonary artery pressures, cardiac output, systemic arterial pressures, ventilator settings, arterial and venous blood chemistries), a lung protective strategy was supported by changing the ventilator mode to time-cycled, pressure-limited (plateau pressure < 30 cmH20), tidal volume monitored ventilation (~6 mL/kg), and a median sternotomy was performed. As previously described by Cryer et. al., the left pulmonary hilum was isolated by gentle positioning of umbilical tape to be used subsequently during the resuscitation phase for ligation as an experimental hemodynamic surrogate of pneumonectomy4, and the chest was covered with plastic wrap to minimize temperature and evaporative water loss. Animals were given warm lactated Ringer's (10 ml/kg) to support pre-hilar manipulation of mean arterial pressure and allowed to stabilize for 15-20 mins. Then, previously described baseline measurements were repeated and echocardiography was performed (Zonare z. one ultra-Ultrasound system; 10-3 probe; Zonare Medical Systems, CA, USA). During echocardiography, the animals were randomized to receive placebo (nitrogen; n =9) or study gas (iNO at 20 ppm; n = 9) delivered just proximal to the inspiratory wyre by the modified iNOmax DSIR delivery system for blinded studies (Ikaria/Mallincrodkt; software version 1.05). Only one member of the study team knew the randomization result; this member was responsible for initiating the placebo or study gas.

The surgical table was elevated to the highest point, transducers were re-zeroed and hemorrhagic shock was then created by passive blood flow from the left femoral artery and internal jugular vein into blood collection bags (JorVet™, Jorgensen Laboratories, Inc. Loveland, CO) positioned 114 centimeters below the animal until a target of 50% of baseline mean systemic arterial pressure (MAP) was reached and sustained for 5 mins. Baseline measurements were then repeated. Within 15 mins of hemorrhagic shock, the resuscitation phase was initiated. Resuscitation consisted of simultaneous ligation of the left pulmonary hilum, infusion of withdrawn blood and initiation of placebo or iNO study gas. To account for single lung ventilation, lung protective ventilation was maintained by monitoring tidal volume via pneumotachography and end-tidal carbon dioxide (NICO CO2 monitor, Philips-Respironics, Wallingford, CT), reducing inspiratory pressure-support thus tidal volume by 33% (plateau pressure < 30 cmH20), increasing frequency to prevent hypercapnea (PaCO2 ≤ 60 mmHg), and titrating FIO2 to maintain SpO2 > 90%. Warm lactated Ringer's solution was infused as needed after completion of blood infusion, to return MAP to baseline. In addition to continuous monitoring of vascular pressures, pulse oximetry, and ECG, blood chemistry and cardiac function were serially measured immediately, 30 minutes, then hourly post-resuscitation to 4 hours post injury or until death.

Pulmonary vascular resistance was calculated from mean pulmonary arterial pressure - pulmonary capillary wedge pressure/cardiac output9. All echocardiographic analysis was performed in a blinded manner following the American Society of Echocardiography guidelines. Cardiac function was assessed using eccentricity index as an indication of RV pressure overload, RV dP/dT and LV ejection fraction as a measure of RV and LV systolic function, respectively, and RV and LV fractional area of change (FAC) as an indicator of respective global ventricular function.

Eccentricity index is a measurement of RV pressure vs. volume overload that is based on interventricular septum movement10, 11. Two measurements of the left ventricle are taken, one perpendicular to the septum and one parallel to the septum11. The ratio of these measurements is taken at end systole and end diastole. In a normal patient, the ratio is 1. If RV volume overload is present, the ratio at end systole is 1, but is >1 at end diastole. If RV pressure overload is present, this ratio will be >1 at both end systole and end diastole. RV fractional area of change (FAC) is a measure of global RV function that has been correlated to RV ejection fraction using MRI10. RV FAC is calculated as (RV end diastole area- RV end systolic area)/ RV end diastole area × 10011. This is measured by tracing the RV endocardium in systole and diastole in an apical four chamber view in the following order: from the annulus, the free wall to the apex, back to the annulus along the intraventricular septum10. A similar measurement is made of the LV cavity. A FAC less than 35% is indicative of systolic dysfunction10.

Data and statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft EXCEL and Graph Pad PRISM. Physiological variables were evaluated by multifactorial ANOVA for time and treatment group with repeated measures on time. Treatment group means were compared vertically using the Dunn-Bonferroni procedure and horizontally to their respective baseline and last injury value using linear contrast. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and significance was accepted at the p < 0.05 level.

Results

As shown in Table 1, there were no significant group differences in body weight, baseline systemic or pulmonary arterial pressures, hematocrit, hemoglobin or blood volume withdrawn to achieve 50% mean arterial pressure. Following instrumentation and initiation of study gas, two animals died prior to the 4 hr end-point. Both animals were in the placebo group. One animal died immediately after ligation of the pulmonary hilum in which there was immediate and extensive right ventricular dilation and cardiac arrhythmia. This animal was excluded from complete statistical analysis. The other animal died from systemic hypotension and arrhythmia at the 2 hr time point. All animals in the iNO treated group survived to 4 hrs. As shown in Figs 1-4 and Table 2 respectively, there were no significant intergroup differences in baseline values for PVR, any measure of cardiac function, shunt, lactate, SvO2, PaO2, or PaCO2.

Table 1.

Group comparisons of body weight, baseline vascular pressures, and blood profile.

| Placebo | iNO | |

|---|---|---|

| Weight | 23.1 | 23.6 |

| kg | 0.78 | 1.2 |

| Baseline MAP | 79 | 78 |

| (mmHg) | 5.4 | 7.1 |

| Baseline mPAP | 27 | 26.6 |

| (cm H2O) | 2.9 | 1 |

| Baseline HcT | 30 | 29 |

| (%) | 1.1 | 2.4 |

| Baseline HgB | 10.3 | 10.2 |

| (g/dL) | 0.47 | 0.84 |

| Blood Withdrawn | 21 | 22 |

| (mL/kg) | 2.8 | 3.2 |

mean ± SEM; n=9/group; MAP: mean arterial pressure; mPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; HcT: hematocrit; HgB: hemoglobin

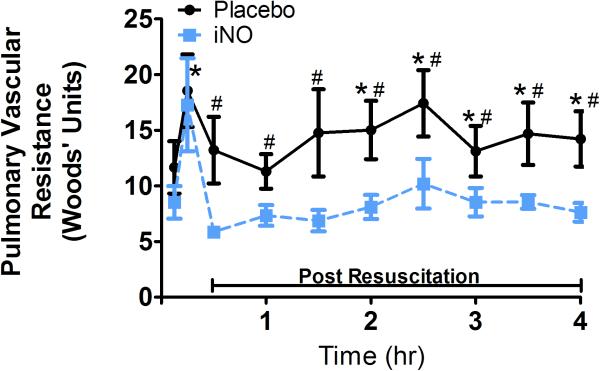

Figure 1. Pulmonary Vascular Resistance.

Pulmonary vascular resistant (PVR) in the placebo and iNO treated groups every 30 minutes from Baseline through 4hrs post resuscitation. (●) placebo (n=9) and (■) iNO (n=9) treated groups. Data shown as mean ± SEM (* p< 0.05 vs baseline; # p< 0.05 vs group)

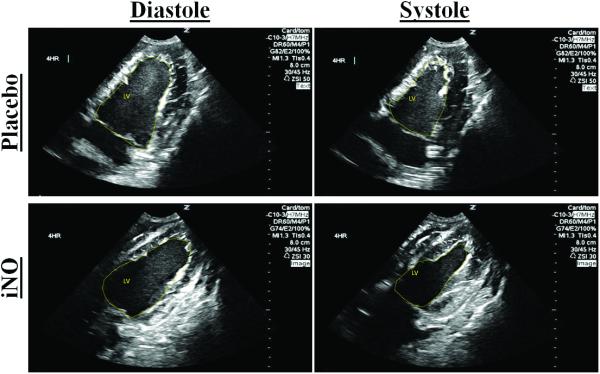

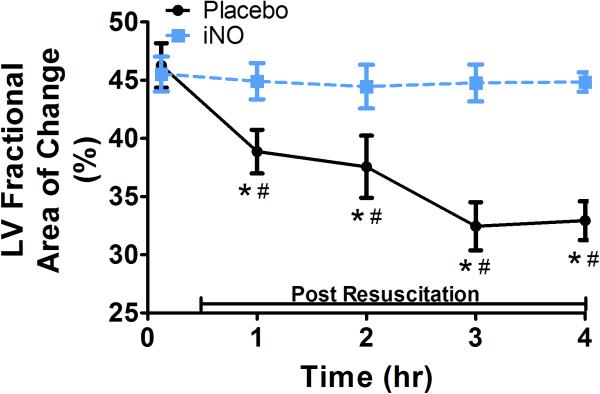

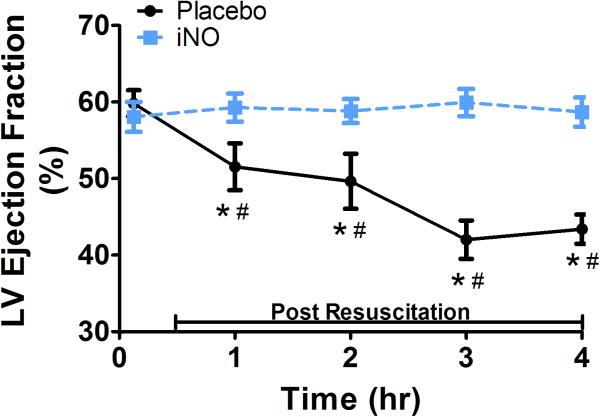

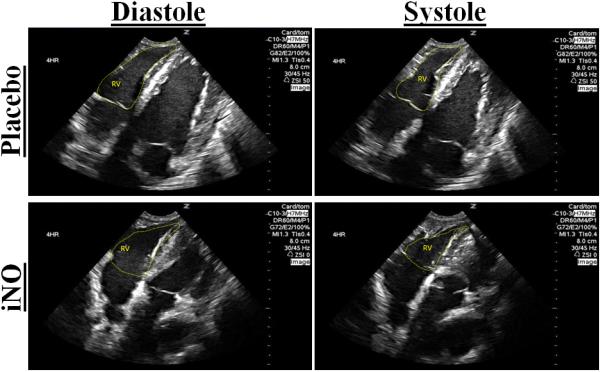

Figure 4. LV Cardiac Function.

(A) Representative traces of the LV areas in diastole and systole in a placebo (top row) and iNO (bottom row) treated animal. These areas were used to calculate the (B) LV fractional area of change (FAC %) and (C) LV ejection fraction (LVEF), over time. (●) placebo (n=9) and (■) iNO (n=9) treated groups. Data shown as mean ± SEM (* p< 0.05 vs baseline; # p< 0.05 vs group)

Table 2.

Group differences in Shunt, Lactate and Mixed Venous Oxygen Saturation as a function of protocol time period.

| Baseline | Initial RP | 4 Hours | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | iNO | Placebo | iNO | Placebo | iNO | |

| Shunt | 4.9 | 4.5 | 22* | 21* | 17.5* | 8.5 §# |

| (%) | 1.6 | 1.1 | 4.4 | 6 | 4.2 | 3.5 |

| Lactate | 1.11 | 1.12 | 3.4* | 2.95* | 6.3* | 3.9*# |

| (mmol/L) | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| SvO2 | 60 | 61 | 27.5* | 29* | 43.2*§ | 61§# |

| (%) | 4.7 | 6.5 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 5.3 | 3.3 |

| PaO2 | 162 | 154 | 81.7* | 89.5* | 135.9*§ | 237.9§*# |

| (mm Hg) | 13 | 12 | 9.7 | 16 | 25 | 21 |

| PaCO2 | 43.2 | 38.3 | 44.5 | 42.2 | 53.6* | 39.1# |

| (mm Hg) | 2.7 | 2.4 | 6.9 | 3.1 | 4.5 | 3.3 |

mean ± SEM; n = 9/group; RP: resuscitation phase

p < 0.05 vs BL

p < 0.05 vs Initial RP

p < 0.05 vs group

Upon initiation of the resuscitation phase, PVR (Fig 1) increased significantly in all animals. In the placebo group, PVR remained elevated from baseline over time. In the iNO group, PVR decreased back towards baseline over time. As shown in Table 2, shunt and lactate increased significantly, SvO2 and PaO2 decreased significantly from baseline initially with the resuscitation phase in both groups. Over time and by 4hr, with placebo, shunt remained elevated relative to baseline, lactate continued to increase, and PaO2 and SvO2, while increasing significantly from the initial resuscitation phase, remained significantly lower than baseline, and PaCO2 was greater than baseline, suggestive of impairment in gas exchange and tissue oxygenation over time. With iNO, shunt, SvO2 and PaO2 improved, and lactate stabilized, reflecting improved tissues oxygenation as compared to placebo treated animals.

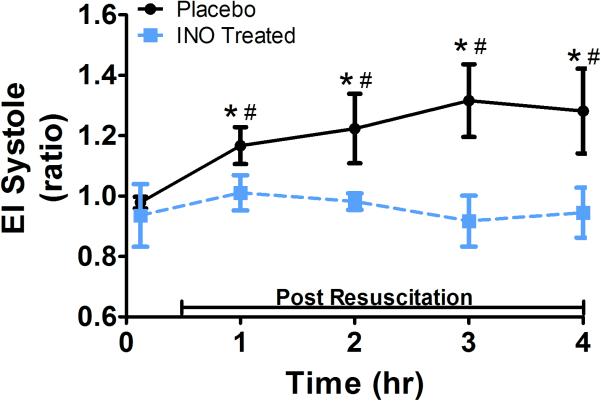

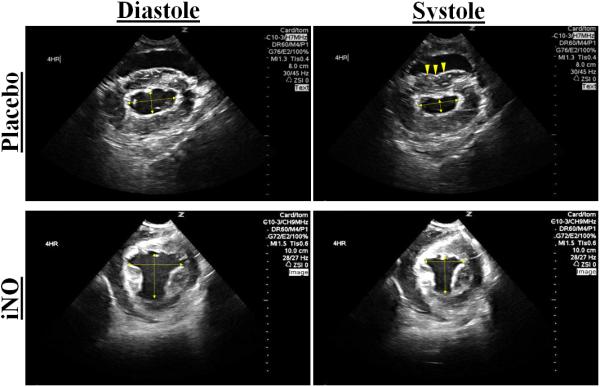

Cardiac function profile is shown in Figs. 2-4 . During the initial resuscitation phase, both placebo and iNO treated groups demonstrated an increase in eccentricity index at end systole (Fig 2) and diastole (not shown), reflective of RV pressure overload. This increase was significantly less in the animals treated with iNO. In the placebo group, the eccentricity index at end systole and diastole continued to increase over time, consistent with a continued increase in RV pressure overload. In contrast, the iNO treated group demonstrated a return to baseline values within 2-3 hours post resuscitation, reflective of return to normal RV pressure loading conditions.

Figure 2. Eccentricity Index.

(A.) Representative 2D short axis echocardiographic images of the left ventricle (LV) in diastole and systole at 4 hr post resuscitation. The placebo images in diastole and systole (top row) shows deformation of the septal wall vs. the iNO treated animal who has maintained a normal cardiac dimensional ratio (bottom row). (B.) The mean eccentricity index (EI) systole (ratio) at baseline, 1,2,3, and 4 hrs post resuscitation in the (●) placebo (n=9) and (■) iNO (n=9) treated groups. Data shown as mean ± SEM (* p< 0.05 vs baseline; # p< 0.05 vs group)

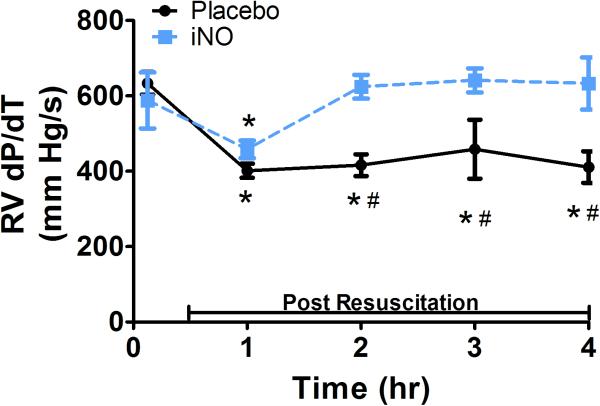

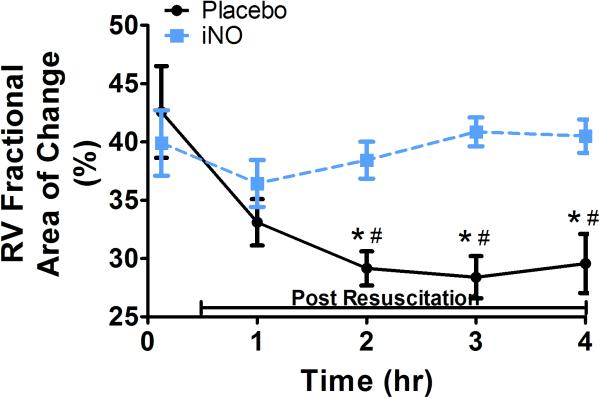

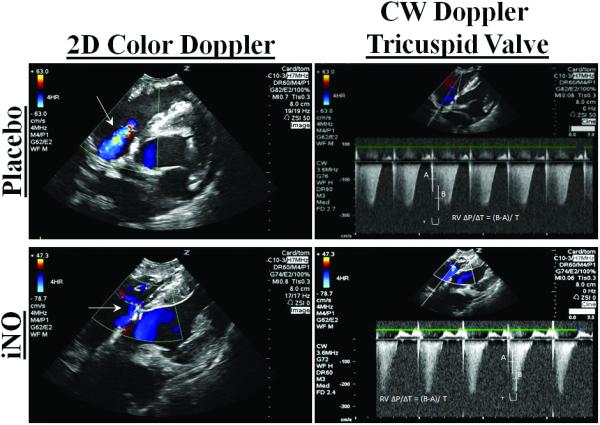

With respect to systolic contractile function, RV dP/dt (Fig 3b) decreased significantly initially post resuscitation in both groups, continued to decrease in the placebo treated animals, and returned to baseline within 2 hrs in animals treated with iNO, reflective of preserved RV contractility. There were significant group differences in bilateral ventricular contractile function as reflected by RV and LV FAC, measurements of global ventricular systolic function. As shown in Fig 3d and Fig 4b respectively, both RV and LV FAC were significantly lower in animals treated with placebo gas as compared to iNO. In addition, while continuing to decrease over time in placebo treated animals suggesting continual impairment of function, RV and LV FAC remained relatively stable in the iNO treated animals. As shown in Fig 4c the group difference in LV function was further demonstrated by the significantly lower and continual decrease in LV ejection fraction over time in animals treated with placebo gas in contrast to the relative stability of this parameter in animals treated with iNO.

Figure 3. RV Cardiac Function.

(A.) Representative 2D color (left column/continuous wave (CW) (right column) Doppler images of the right ventricular (RV) inflow tract 4 hrs post resuscitation in a placebo (top row) and an iNO (bottom row) treated animal. The placebo animals had greater regurgitation during systole vs. the iNO treated animals. (B) RV dP/dT, was calculated from the CW Doppler of the regurgitation flow at baseline, 1,2,3, and 4 hrs post resuscitation. (C) Representative traces of the RV areas in diastole and systole in a placebo (top row) and iNO (bottom row) treated animal. These areas were used to calculate the (D) RV fractional area of change (RV FAC%) at baseline, 1,2,3 and 4 hrs post resuscitation in each group. (●) placebo (n=9) and (■) iNO (n=9) treated groups. Data shown as mean ± SEM (* p< 0.05 vs baseline; # p< 0.05 vs group)

Discussion

This study demonstrates that iNO mitigated the increase in pulmonary vascular resistance, thus decreasing right ventricular afterload and risk of right ventricular failure following combined hemorrhage and pneumonectomy in the sheep. Our animal model, similar to the pig model previously reported by Cryer et. al.4 simulated the clinical situation of patients who have central hilar injuries causing hemorrhagic shock and who require pneumonectomy for control. Upon ligation, with the removal of one of the two parallel circuits of the pulmonary circulation, there was an acute and robust increase in PVR in both groups of animals. Cardiac instability, including right ventricular dilation, and hemodynamic compromise was observed as previously reported in both animal and humans1-4, 7, 8. In our study, animals treated with placebo gas demonstrated progressive right heart failure as has been demonstrated in humans with hemorrhagic shock and trauma pneumonectomy3; whereas, animals treated with iNO demonstrated the return of elevated PVR back to baseline and preserved right ventricular function.

The return of PVR towards baseline supports the notion that iNO was effectively delivered to the alveolar-capillary membrane to diffuse into the pulmonary smooth muscle cells, activate soluble guanylate cyclase to convert GTP to cGMP thereby increasing intracellular concentrations of cGMP thus facilitating pulmonary vascular smooth muscle relaxation and decrease in PVR. Animals that received iNO had less RV pressure overload (eccentricity index), preserved RV systolic function (RV dp/dt, RV FAC), and preserved LV function (LV EF, LV FAC). Functionally, an interpretation of this finding is that this translated to preserved tissue oxygenation, as demonstrated by the stabilized lactate values and the return of mixed venous oxygen saturation to baseline values. Preservation of RV function and tissue oxygenation seen with iNO in the present study is consistent with that previously demonstrated in humans with acute right heart failure. In this regard, patients in acute right heart failure treated with iNO were reported to respond with a decrease in PVR, pulmonary pressures, increased cardiac output and ultimately improved tissue perfusion5. Several case studies suggest the saluatory effect of iNO on survival following hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy 7, 8. One report described survival following pneumonectomy subsequent to bilateral blunt thoracic injury in which iNO was initiated post-operatively and maintained for 4 days 8. Another case study reported a 24 year old patient with a right pulmonary artery injury who received pneumonectomy with initial worsened RV function, who was then treated with iNO experienced reduced pulmonary artery pressures, improved cardiac output and ultimately survived7.

In contrast, in animals that received placebo gas (nitrogen), PVR remained elevated which was associated with worse RV function than animals treated with iNO. The placebo animals experienced continued RV pressure overload, decreased global RV systolic function, abnormal motion of the interventricular septum and ultimately reduced LV EF. This translated to poorer tissue oxygenation, as demonstrated by the blood lactate levels, which remained elevated in these animals and the persistently low mixed venous oxygen saturation. The impaired right heart function seen in the placebo animals is consistent with current theories that increased RV afterload (via increased right ventricular end diastolic volume) ultimately decreased RV ejection fraction4, 5, leads to decreased left ventricular end diastolic volume (preload) and ultimately decreased cardiac output5. Additionally, RV afterload in this scenario may be increased due to the combination pulmonary vasoconstriction, decreased vascular compliance and microvascular plugging4. This is likely exacerbated by hemorrhagic shock, in which thromboxane release and leukostasis have the potential to interfere with vascular recruitment, leading to vasoconstriction and plugging that further reduces the ability of the RV to compensate ultimately leading to RV failure4. These vascular effects also have the potential to lead to pulmonary edema, precipitating worsening hypoxemia and potentially worsening pulmonary hypertension2. This vicious cycle of hypoxemia and pulmonary hypertension leading to RV failure contributes to the demise of these patients as the RV is not able to compensate for the vast increase in PVR.

Our data suggest that iNO is able to selectively vasodilate the pulmonary vasculature, thus decreasing PVR in the setting of hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy. This decrease in PVR leads to reduction in RV afterload and preserved RV and LV function. Ultimately, this yields improved tissue oxygenation and potentially survival, in cases when the right heart struggles to compensate in the face of increased afterload.

There are several unique strengths of this study. In contrast to previous pre-clinical studies, we chose to initiate iNO treatment simultaneous with surgical and volume resuscitation. In this regard, our study offers insight to the potential prophylactic application of iNO in the setting of hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy. In addition, in an attempt to minimize confounding variables which could impact interpretation, we chose to restrict rescue management to surgical resection, return of autologous blood, and iNO rather than to other additional support of hemodynamic and metabolic status with vasopressors and buffers. Some limitations of the present study should be noted. We recognize that in comparison to massive hilar hemorrhage our method of hemorrhage from central and peripheral vessels does not present the same clinical challenges with respect to surgical, vascular control, and blood collection for autotransfusion. Based on our interest in the immediate hemorrhagic shock and pneumonectomy resuscitation period, we chose a 4 hour study window as previously described4. As such, from this observation period we can speak only to the short-term benefits of iNO. Nonetheless, our degree of hemorrhage, study period and alterations in lactate levels paralleled the acuity and intensity experienced by our clinical Trauma team and lends insight to the saluatory rescue potential of this approach. Other potential considerations are related to echocardiography. Whereas all measurements were performed by experienced sonographers, they were performed with the open-chest approach which may limit translation to the clinical experience. We recognize that certain echocardiography measurements are load dependent and that loading conditions are likely to change over time in a study of this nature. With this in mind, given that both groups were managed in the same way apart from the study gas, we submit that this would impact each group comparably. By nature, there is an element of subjectivity in echocardiogram analyses which may potentially lead to variations in interpretation. This variation was minimized by having all echocardiograms evaluated by the same skilled sonographer. As such, we believe that this is not a likely source of bias in our study.

Summarily, these data provide strong evidence that iNO can be a useful treatment to decrease PVR and reduce RV afterload. Within this context, this study suggests that iNO can be a useful clinical adjunct to mitigate right heart failure and potentially improve survival in the face of hemorrhagic shock when pneumonectomy is required. Further research is warranted to determine iNO management strategies (ie. dose, duration, weaning; longer durations of shock, with hilar hemorrhage) in this patient population.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sandy T. Baker, MLAS for his contribution in overall laboratory support, Gennaro Calendo, BS for his supportive role in animal preparation, and Lucas Ferrer, MD and Sarah Koller, MD for their contribution in preparing the applications to the institutional animal care and use committee and to Ikaria/Mallincrodkt.

Materials and/or personnel involved with this project were supported by grants received from Ikaria/Mallincrodkt (LOS) and the DoD/ONR (MRW: N000141210810; N000141210597).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: All authors have completed the appropriate disclosure forms

This manuscript was presented at the 75th annual meeting of the American Association for the Surgery for Trauma, September 14-17, 2016, in Waikoloa, Hawaii.

Author Contribution: L.O.S. and M.R.W. were responsible for overall experimental design and were directly involved with study implementation, data collection/analysis, and interpretation, and manuscript development. A.L.L. was involved in study implementation, data collection/analysis and interpretation and manuscript development. L.A.P. and J.W., T.E.S., M.W., and R.M.B. were involved in study implementation, data collection/analysis/interpretation and manuscript review. A.G., A.P., and T.S. were involved with review of results and interpretation with specific attention to clinical translation.

References

- 1.Alfici R, Ashkenazi I, Kounavsky G, Kessel B. Total pulmonectomy in trauma: a still unresolved problem--our experience and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2007;73(4):381–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgartner F, Omari B, Lee J, Bleiweis M, Snyder R, Robertson J, Sheppard B, Milliken J. Survival after trauma pneumonectomy: the pathophysiologic balance of shock resuscitation with right heart failure. Am Surg. 1996;62(11):967–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halonen-Watras J, O'Connor J, Scalea T. Traumatic pneumonectomy: a viable option for patients in extremis. Am Surg. 2011;77(4):493–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cryer HG, Mavroudis C, Yu J, Roberts AM, Cue JI, Richardson JD, Polk HC., Jr. Shock, transfusion, and pneumonectomy. Death is due to right heart failure and increased pulmonary vascular resistance. Ann Surg. 1990;212(2):197–201. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199008000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhorade S, Christenson J, O'Connor M, Lavoie A, Pohlman A, Hall JB. Response to inhaled nitric oxide in patients with acute right heart syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(2):571–579. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.2.9804127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths MJ, Evans TW. Inhaled nitric oxide therapy in adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(25):2683–2695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra051884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nurozler F, Argenziano M, Ginsburg ME. Nitric oxide usage after posttraumatic pneumonectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(1):364–366. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein Y, Kishinevsky E, Konichezky S, Bregman G, Klein M, Kashtan H. Postoperative Management after Pneumonectomy for Blunt Thoracic Trauma. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2007;33(4):422–424. doi: 10.1007/s00068-007-6033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellofiore A, Chesler NC. Methods for measuring right ventricular function and hemodynamic coupling with the pulmonary vasculature. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41(7):1384–1398. doi: 10.1007/s10439-013-0752-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudski LG, Lai WW, Afilalo J, Hua L, Handschumacher MD, Chandrasekaran K, Solomon SD, Louie EK, Schiller NB. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(7):685–713. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryan T, Petrovic O, Dillon JC, Feigenbaum H, Conley MJ, Armstrong WF. An echocardiographic index for separation of right ventricular volume and pressure overload. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5(4):918–927. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80433-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]