Abstract

Pediatric obesity is a public health concern. High attrition from treatment negatively impacts outcomes, particularly among lower income and ethnic minority populations. NOURISH+ is a parent-exclusive childhood weight management treatment targeting at-risk children aged 5–11 years who are overweight or obese. The current study sought to enhance understanding of attrition among at-risk families. NOURISH+ participants completed a survey assessing barriers to treatment adherence. Among low-income, racially diverse families, practical barriers are pressing concerns. The NOURISH+ parent-exclusive approach, although empirically supported, appears inconsistent with caregivers’ expectations. Minimizing practical barriers and enhancing child engagement might reduce attrition and improve outcomes.

Keywords: pediatric obesity, attrition, weight management, parent

Introduction

Pediatric overweight and obesity affect over 30% of children in the U.S.1 African American and Hispanic children, as well as children from low-income households, are at disproportionate risk of these conditions.2,3 Family-centered interventions are the most effective approaches to pediatric obesity treatment.4,5 Moreover, for young children, parent-only approaches demonstrate efficacy and are cost-effective.6 However, although effective pediatric obesity treatments are available, attrition and poor adherence remain significant barriers to positive outcomes.7 Attrition is particularly high among ethnic/racial minority and low-income families, groups which experience disproportionate risk of obesity.8,9

Nourishing Our Understanding of Role modeling to Improve Support and Health (NOURISH+) is a parent-focused, randomized controlled trial targeting racially diverse families with overweight and obese children aged 5–11 years.10 (Please refer to Mazzeo et al., 201210 for details on the trial design, including descriptions of intervention and control groups). NOURISH+ uses several strategies to enhance treatment engagement, including implementing culturally sensitive intervention approaches, providing graduated incentives for completing assessments, making frequent participant contact (e.g., reminder calls and mailings prior to sessions and assessments), offering treatment in convenient locations, and providing childcare.11–13 Despite these efforts, many families do not attend all group sessions and others are lost to follow up or do not attend post-testing (see Participants section for specific attrition details). This study investigated treatment barriers experienced by caregivers previously enrolled in NOURISH+ to inform future iterations of the program and related obesity interventions targeting this high-risk population.

Material and Methods

Participants

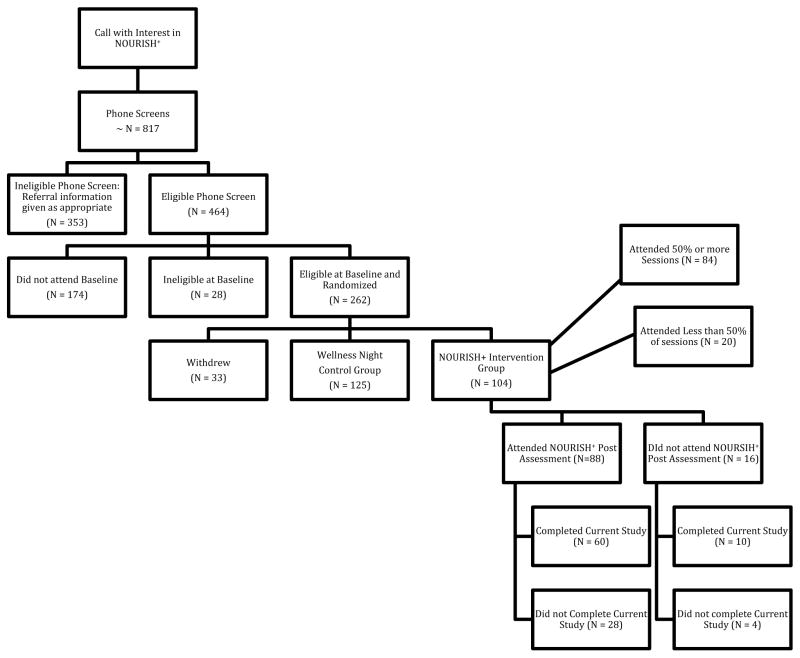

Caregivers previously enrolled in the NOURISH+ intervention (waves 1–15 of this ongoing trial), were re-contacted for this study (regardless of whether they had completed post-testing). NOURISH+ includes baseline assessment, six group sessions, and post-assessment (as well as follow-ups, which are not reviewed in this manuscript). In this study, treatment engagement was operationalized as the number of sessions attended (0–6). Among eligible caregivers, only 7.7% did not attend any sessions following baseline assessment. Session attendance rates were as follows: 31.7% attended at least 50% of the sessions (3 of 6), 68% of eligible caregivers attended at least four of the six sessions, and 19.2% attended all six intervention sessions. The average number of sessions attended was M=3.9, SD=1.8. Additionally, 84.6% of eligible caregivers attended post-assessment. Figure 1 presents the flow of participants through NOURISH+ and this study.

Figure 1.

NOURISH+ Recruitment and Enrollment Flow Chart

Procedure

Caregivers were contacted using their preferred method as indicated at NOURISH+ enrollment. Primary contact was predominantly by phone; e-mail was used when phone calls did not yield contact with participants. After four unsuccessful primary and secondary contact attempts, communication attempts ceased. Caregivers who consented to the current study’s questionnaire are subsequently referred to as “participants” and those who declined or could not be contacted are referred to as “non-participants.”

Measure

The questionnaire used in this study included both quantitative and open-ended items,14 and was based, in part, on an assessment used in an Australian investigation of attrition from an adolescent obesity intervention.14 Additional items for this study were generated by investigators and informed by existing pediatric obesity literature. These 41 items (see Table 1) assessed eight categories of potential barriers to participation: research demands, treatment approach, program components and strategies, clinical factors, comfort participating, practical barriers, individual and family demands, and health and well-being. Participants indicated whether each item represented a barrier to their participation on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 2 (a lot). Qualitative data were obtained via six open-ended items that explored participants’ perspectives on barriers and facilitators to treatment engagement (Table 2).

Table 1.

Severity of each item as a barrier to session attendance (none, low, high) and a mean severity rating for each questionnaire item.

| Questionnaire Item by Category | Frequency of caregiver endorsement | Mean Severity Rating | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not a barrier “0” | Low severity “1” | High severity “2” | Range 0–2 | |

| Research Demands | 1.2 | |||

| 1. I did not like completing the questionnaires | 48 | 19 | 3 | .36 |

| 2. My child and I did not like completing the physical assessment | 58 | 10 | 2 | .20 |

| 3. I had to wait too long to start the program | 67 | 3 | 0 | .04 |

| Treatment Approach | 1.4 | |||

| 4. The program did not deal with the causes of my family’s problems | 54 | 15 | 1 | .24 |

| 5. Instead of working with my child, the program focused too much on me | 41 | 20 | 9 | .54 |

| 6. The program was not working | 59 | 9 | 2 | .19 |

| 7. I would have preferred an individual program | 43 | 19 | 8 | .50 |

| 8. I would have preferred a self-help program | 51 | 14 | 5 | .34 |

| Program Components and strategies | 1.1 | |||

| 9. The behavior change goals were too hard | 60 | 9 | 1 | .16 |

| 10. There were too many behavior change goals involved | 63 | 6 | 1 | .16 |

| 11. The program sessions were boring | 62 | 7 | 1 | .13 |

| 12. The program was difficult to understand | 67 | 2 | 1 | .06 |

| 13. The program took too much time | 61 | 5 | 4 | .19 |

| 14. The topics of the sessions were not relevant to my family | 59 | 8 | 3 | .20 |

| 15. The format was too structured | 67 | 2 | 1 | .06 |

| Clinician Factors | 1.0 | |||

| 16. The leaders way of talking was hard to understand | 68 | 2 | 0 | .03 |

| 17. The leaders had different values or beliefs than me | 65 | 3 | 2 | .10 |

| 18. The leaders put too much pressure on me | 69 | 1 | 0 | .01 |

| 19. The leaders did not seem to have enough qualifications | 68 | 1 | 1 | .04 |

| Uncomfortable Participating | 1.2 | |||

| 20. I did not feel comfortable talking about my family | 67 | 3 | 0 | .04 |

| 21. My child did not want to make an effort to participate in the program | 58 | 9 | 3 | .21 |

| 22. I was nervous about taking part in the program | 55 | 12 | 3 | .26 |

| 23. I did not think my child had a problem | 59 | 7 | 4 | .21 |

| 24. I wasn’t ready to make the changes that the group discussed | 60 | 9 | 1 | .16 |

| 25. I would have preferred the program was given directly to my child instead of me | 52 | 13 | 5 | .33 |

| 26. I didn’t feel like I was making as much progress as other people in the group | 53 | 15 | 2 | .27 |

| Practical Barriers | 1.4 | |||

| 27. Getting to the sessions was difficult because of transportation | 59 | 3 | 8 | .27 |

| 28. I had a long way to travel to sessions | 44 | 8 | 18 | .63 |

| 29. Session times were not convenient | 49 | 14 | 7 | .40 |

| 30. My family responsibilities interfered with coming to sessions | 46 | 17 | 7 | .44 |

| 31. My work schedule interfered with coming to sessions | 56 | 9 | 5 | .27 |

| 32. I wanted to be in the less intensive group/the group that only met one time for the wellness night | 64 | 4 | 2 | .11 |

| Individual and Family Demands | 1.2 | |||

| 33. My family had too many other problems occurring at the same time | 59 | 7 | 4 | .21 |

| 34. There were too many pressures going on around me | 58 | 6 | 6 | .26 |

| 35. I was having financial problems that the group didn’t understand | 62 | 6 | 2 | .14 |

| 36. I did not want to participate because the program interfered with other aspects of my life | 69 | 1 | 0 | .01 |

| 37. Other members of the family made it difficult for me to make the changes I wanted to make | 50 | 13 | 7 | .39 |

| Health and Well Being | 1.1 | |||

| 38. My health made it difficult to participate | 62 | 7 | 1 | .13 |

| 39. I was feeling too unhappy to participate | 69 | 1 | 0 | .01 |

| 40. My child was feeling too unhappy to participate | 64 | 6 | 0 | .09 |

| Attrition | ||||

| 41. I stopped coming because I felt like I missed too many sessions | 64 | 6 | 0 | .09 |

Table 2.

List of open-ended question prompts from attrition survey.

| Open-Ended Questions |

|---|

| 1. What would you say was the issues that made it the most difficult to attend? |

| 2. What do you think was the hardest part for you about completing this study? |

| 3. Was there anything about the program that you felt made it easier to attend? |

| 4. What do you think would help families like yours attend this intervention? |

| 5. If you could make any recommendations to the program, what would they be? |

| 6. What about the leaders? Would you have liked them to be different in any way? What characteristics would you have preferred in a group leader? |

Analyses

SPSS v22 was used for analyses. Frequencies, independent samples t-tests and Mann Whitney U tests were conducted to determine if participants differed significantly from non-participants on demographics (race, parent body mass index [BMI], child BMI percentile, household income and parental education).

Descriptive analyses were conducted for each item. Frequency ratings indicated how often each item was perceived as a barrier to attendance (rating of “1” or “2”) and how often barriers were not relevant to attendance (rating of “0”). For each item, an overall mean severity rating was also calculated (Table 1).

Items were subsequently collapsed into eight categories (research demands, treatment approach, program components and strategies, clinical factors, comfort participating, practical barriers, individual and family demands, and health and well-being) Further, a mean severity rating was calculated for each of the eight categories as well as for each questionnaire item. Correlations between each category and the number of sessions attended were examined. If correlations indicated a significant relation between item category and attendance, a follow up multiple regression was conducted to determine which category item (or items) contributed significantly to the association.

Results

Representativeness of Current Study Sample

Sixty seven percent (N=70; 98.5% female) of eligible caregivers participated in this study; (84.3% of these caregivers completed NOURISH+ post-testing). Participants in this study were representative of the entire NOURISH+ sample with respect to race, parent BMI, and child BMI percentile (p >.05). Of all eligible NOURISH+ participants, 71.2% identified as African American, 21.2% as White, 1.9% as Hispanic, 2.9% as other or multi-racial, 1.0% as American Indian/Alaskan Native and 1.9% of participants declined to provide a racial category. Of those who participated in this study, 71.4% identified as African American, 25.7% as White, and 2.9% as Hispanic/Latino.

Parents’ BMIs were similar in both the overall NOURISH+ sample and the subsample included in this study (p=.98). In both groups, the majority of caregivers (66.6% in overall NOURISH+ and 65.6% in this sample) had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, indicative of obesity. Additionally, there were no significant differences between study participants (M=96.33, SD=4.01, n=69) and non-participants (M=95.71, SD=5.5, n=34) on child BMI percentile, t(101)=.649, p=.518. Further there were no significant differences among child age at baseline between participants (M = 8.86, SD = 1.70) and non-participants (M = 8.06, SD = 2.23), t(95) = 1.963, p = .53.

Differences between the NOURISH+ overall sample and this sample on reported household income and parental education were also explored. Results indicated that current study participants reported higher household income than non-participants (U=670.5, Z=−2.816, p=.005). Lastly, the NOURISH+ sample and this sample reported comparable levels of parental education. In both groups, over half of caregivers had some college education (52.8% in overall NOURISH+ and 52.9% in the current sample).

Factors Associated with Attendance

Session attendance was most strongly associated with practical barriers (r=−.362, p<.001). Specifically, when families perceived practical issues as a large barrier to attendance, they were less likely to attend. A follow up multiple regression was conducted with each practical barrier item as an independent variable and session attendance as the dependent variable, to examine the influence of specific practical barriers on this association. The overall model was significant F(6, 63)=6.357, p<.001, R =.377. However, only one item, session time, accounted for significant variance in attendance (β=−1.306, p<.001).

Evaluation of the items receiving the highest severity rating indicated parental concern regarding child involvement, preference for an individual program, travel distance, session time, and family schedule barriers were among the most pressing barriers to session attendance.

Responses to the open-ended items indicated that many caregivers (n=26) thought NOURISH+ was too parent-oriented, and children were not adequately involved. These parents expressed a desire for enhanced child involvement to improve child motivation, engagement, and understanding. Suggestions included separate child sessions, joint parent/child sessions, more interaction between children and group leaders, activities for children related to intervention content, and opportunities for child physical activity.

Caregivers also detailed difficulties they experienced regarding travel distance and time, and session scheduling. Specific concerns included difficulty obtaining free parking in the program’s urban location (although parking vouchers were provided by study staff), unreliable personal transportation, reliance on public transit, traffic, and trouble prioritizing session attendance while juggling other family responsibilities. Each of these concerns posed barriers to session attendance. Families infrequently endorsed clinician factors, discomfort participating, program components, or family health and well-being as relevant barriers to participation. Although 41.4% of caregivers endorsed the item indicating a preference for an individual program in the quantitative assessment, many noted in their open-ended responses that the group format enabled them to connect with other parents in similar circumstances in a setting that facilitated open dialogue. This result suggests parents benefited from, and enjoyed, the group format.

Discussion

Reducing attrition in pediatric obesity treatments is of paramount importance, particularly among lower income and African American families, who are at high risk for obesity and its comorbidities.1,15 Research has demonstrated the relative efficacy and cost-effectiveness of parent-exclusive pediatric weight management programs.6 Nonetheless, attrition continues to attenuate treatment outcomes. This study examined factors influencing attrition within a parent-exclusive pediatric obesity treatment targeting racially diverse families. Results highlight the ongoing need to enhance retention by reducing practical barriers to participation, and enhancing the fit between intervention structure and parents’ expectations.11,16,17

Current findings are consistent with prior attrition research, which demonstrates that practical barriers and individual and family demands are among the most commonly reported hindrances to program engagement.7,8,11 Families in the current study identified several program barriers that could be addressed by program facilitators (e.g., parking, time, distance, scheduling), thereby increasing the likelihood for optimizing program engagement. However, many of these issues were already addressed by program staff, including providing parking vouchers and offering the program on multiple days and times. Thus, results also suggest that it is unlikely that any one time will be ideal for all families. Future research should consider the use of alternative intervention delivery modalities such as online, interactive, group settings to facilitate treatment access.

Additionally, results indicate that parental perspectives on the appropriate level of child involvement in weight management programs are very important. Although NOURISH+ intentionally focuses on parents as the agents of change for their families, and this rationale is articulated several times during the recruitment, consent, and intervention processes, parents continued to express concern over the lack of direct child engagement. These findings emphasize the need for innovative strategies to increase family-program “fit.” The incorporation of interactive, child-focused activities into family-based treatments might boost both child and parental engagement and decrease attrition. Low-intensity interventions (e.g., a Fitness Night, High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) for children, child-focused nutrition education, meal-planning activities) with enrolled children might address parent concerns without adding excessive intervention components. Parental suggestions via open-ended responses indicated a desire for additional child-centered education regarding nutrition and physical activity (e.g. portion size, healthy snacks, importance of healthy eating, kid-friendly exercises). Current findings suggest parents might be more invested in attending sessions when their children are more involved, and practical barriers are adequately addressed.

This study’s sample is generally representative of the overall NOURISH+ sample. Thus, findings are largely generalizable to all NOURISH+ participants. However, families who participated in this study reported higher incomes than those that did not participate, introducing some potential bias. Also, because there was some time between participants’ completion of NOURISH+ and this study, participants might have had difficulty recalling specific aspects of the program or their participation. Finally, although this study identified recommendations to improve participant retention in parent-focused pediatric obesity treatment, it did not assess the potential impact of these suggestions on outcomes. Future research should attempt to integrate these recommendations into clinical practice and evaluate their impact on attrition.

Despite these limitations, this study does have several strengths. Specifically, it is one of the few to investigate attrition from a culturally sensitive weight management intervention targeting a lower-income, predominantly African American sample.18 This study is also one of the first to describe parental perceptions of program feasibility following a parent-focused intervention as previous studies of patient attrition focus on interventions with relatively equal parent and child involvement. Further, this study utilized a mixed method approach to enhance understanding of barriers and facilitators to program engagement. Future studies should continue to investigate strategies to enhance engagement and reduce attrition in pediatric obesity interventions targeting high risk populations.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the National Institute of Health [R01HD066216]. This clinical trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov [NCT01361243]

We thank Dr. Rosalie Corona for guidance on this project.

Footnotes

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01361243

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker RE, Keane CR, Burke JG. Disparities and access to healthy food in the United States: A review of food deserts literature. Health Place. 2010;16(5):876–884. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalinowski A, Krause K, Berdejo C, Harrell K, Rosenblum K, Lumeng JC. Beliefs about the role of parenting in feeding and childhood obesity among mothers of lower socioeconomic status. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2012;44(5):432–437. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison KK, Lawson HA, Coatsworth JD. The Family-centered Action Model of Intervention Layout and Implementation (FAMILI): the example of childhood obesity. Health Promot Pract. 2012;13(4):454–461. doi: 10.1177/1524839910377966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Wrotniak BH, et al. Cost-effectiveness of family-based group treatment for child and parental obesity. Child Obes. 2014;10(2):114–121. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Golan M. Parents as agents of change in childhood obesity – from research to practice. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1(2):66–76. doi: 10.1080/17477160600644272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball GDC, Perez Garcia A, Chanoine J-P, et al. Should I stay or should I go? Understanding families’ decisions regarding initiating, continuing, and terminating health services for managing pediatric obesity: the protocol for a multi-center, qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):486. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barlow SE, Ohlemeyer CL. Parent Reasons for Nonreturn to a Pediatric Weight Management Program. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2006;45(4):355–360. doi: 10.1177/000992280604500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skelton JA, Irby MB, Beech BM, Rhodes SD. Attrition and family participation in obesity treatment programs: clinicians’ perceptions. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(5):420–428. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazzeo SE, Kelly NR, Stern M, et al. Nourishing Our Understanding of Role Modeling to Improve Support and Health (NOURISH): design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(3):515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hampl S, Paves H, Laubscher K, Eneli I. Patient engagement and attrition in pediatric obesity clinics and programs: results and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2011;128(Suppl) Supplement_2:S59–S64. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0480E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ross MM, Kolbash S, Cohen GM, Skelton JA. Multidisciplinary treatment of pediatric obesity: nutrition evaluation and management. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25(4):327–334. doi: 10.1177/0884533610373771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skelton JA, Beech BM. Attrition in paediatric weight management: a review of the literature and new directions. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e273–e281. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan L, Walkley J, Wilks R. Parent- and adolescent-reported barriers to participation in an adolescent overweight and obesity intervention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(6):1319–1324. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakshman R, Elks CE, Ong KK. Childhood obesity. Circulation. 2012;126(14):1770–1779. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.047738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen CD, Aylward BS, Steele RG. Predictors of attendance in a practical clinical trial of two pediatric weight management interventions. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2012;20(11):2250–2256. doi: 10.1038/oby.2012.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller BML, Brennan L. Measuring and reporting attrition from obesity treatment programs: A call to action! Obes Res Clin Pract. 2015;9(3):187–202. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzeo SE, Kelly NR, Stern M, et al. Nourishing Our Understanding of Role Modeling to Improve Support and Health (NOURISH): design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(3):515–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]