Abstract

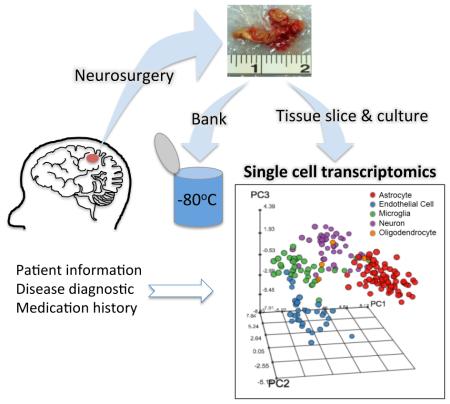

Investigation of human CNS disease and drug effects has been hampered by the lack of a system that enables single cell analysis on live adult patient brain cells. We developed a culturing system, based on a papain-aided procedure, for resected adult human brain tissue removed during neurosurgery. We performed single-cell transcriptomics on over 300 cells permitting identification of oligodendrocytes, microglia, neurons, endothelial cells, and astrocytes after 3 weeks in culture. Using deep sequencing, we detected over 12,000 expressed genes including hundreds of cell-type enriched mRNAs, lncRNAs and pri-miRNAs. We describe cell-type and patient specific transcriptional hierarchies. Single-cell transcriptomics on cultured live adult patient derived cells is a prime example of the promise of personalized precision medicine. As these cells derive from subjects ranging in age into their sixties, this system permits human aging studies previously possible only in rodent systems.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The adult human brain is composed of an intricate network of multiple cell types that interact in direct and indirect ways. Diseases and drugs uniquely and differentially target these various cell types. Single cell studies allow the highest resolution to assess this variability and cell type specific effects. Most past single cell neuronal cell work has been performed in rodents (Dueck et al., 2015; Miyashiro et al., 1994; Tasic et al., 2016; Zeisel et al., 2015). Cell type studies in humans have been largely limited to post mortem studies (Hawrylycz et al., 2015; Lake et al., 2016), cancer cell lines, and more recently, acute harvest of cells from patients (Darmanis et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). While these studies provide valuable human transcriptomic information, the cells’ acute harvest provides no means for morphological or long-term functional investigation other than sequencing. Cell selection methods limit the collection to subpopulations of each cell type and nuclei sequencing likely results in an incomplete picture of the entire transcriptome. Some studies have focused on human embryonic stem cell (ES) and iPS derived neurons to create iN (induced neuron) cells that can produce de novo synaptic connections (Zhang et al., 2013). For studying human CNS disease and drug effects, patient-derived fibroblasts used for iPS cells and stem cells are distinctly affected by disease and drug therapy. Developing and validating a model system that is easily manipulated to investigate the function and responsiveness of a broad range of cell types in the human brain is needed. A culture system that supports long term survival of multiple adult cell types harvested from the adult human brain would enable an understanding of human cell type specific gene regulation without the confounding effects of species differences, cell line effects or those introduced by trans-differentiation.

We have developed a culturing system for healthy adult human brain cells from patient biopsies collected at the time of surgery. These cells were cultured up to 84 days in vitro (DIV) and analyzed with deep sequencing of hundreds of single cells to obtain their individual RNA expression profiles. The single cell resolution of this study allows us to measure the range and variance of expression of key genes and shows that mouse-derived cell type markers can be inappropriate discriminators of human cell types (Darmanis et al., 2015; Hawrylycz et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). Use of human sourced enriched gene lists supported by functional pathway analysis resulted in consistent identification of cell types and subtypes using multiple bioinformatic and statistical methods (K-means clustering, GO annotation enrichment, etc.). We further identified cell type enriched pri-miRNA and lncRNA as well as potential transcription factor control pathways of genes that are candidates for driving the expression of subpopulations of the cell type defining genes.

We find that cells maintain their cell type classification throughout their time ex vivo. Morphological analysis of transcriptome-profiled cells suggests that transcriptionally distinct cell types can have a wide range of cell morphology in culture (Zhang et al., 2016) that we extend to other cell types. The human culturing system allows long-term maintenance and characterization of cells derived from a broad range of age groups (the oldest subject assessed was 63 years old). Importantly, such primary cell cultures by design will be absent their in vivo cellular connections as the natural microenvironment has been disrupted and hence will be somewhat different from their in vivo cellular counterparts. However the ease of use and decades of fundamental and clinical data resulting from primary cells suggests that cultured adult human brain cells will be useful in understanding the fundamentals of neuronal cell functioning and responsiveness. This adult human primary cell culture resource provides a means for CNS drug testing.

Results

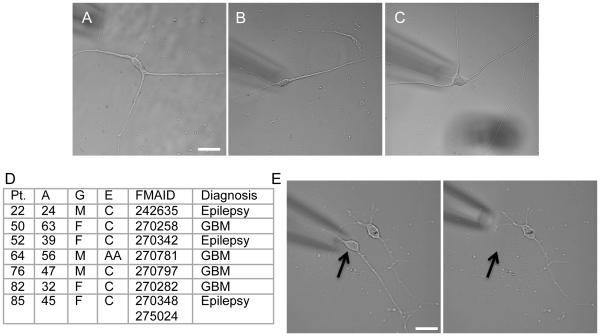

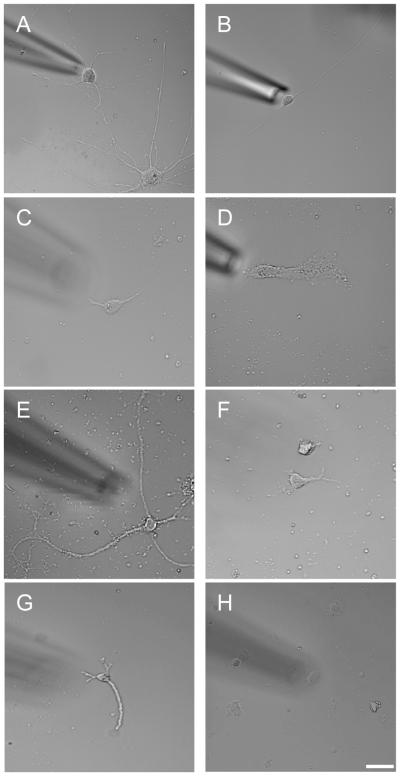

Cortical and hippocampal biopsies were collected from seven patients at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Three of the patients were diagnosed with epilepsy and the remainder diagnosed with a brain tumor, e.g. glioblastoma -WHO grade IV- at a distance from the cortical biopsy site (6.825±2.484mm standard deviation, Fig. S1). Four were Caucasian females, two Caucasian males, and one African American male, ranging in age from 24 to 63 years. Tissues were delivered to the laboratory in ice-cold oxygenated aCSF approximately 10 minutes post excision. The tissue was dissociated, plated, and maintained in an incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2. The cells in primary cell culture displayed complex morphological characteristics with smooth processes when present and no obvious vacuoles, highlighting their overall health (Chen et al., 2011), Fig. 1A-C). Cells were collected by pipette aspiration between 1 and 84 days after plating (Fig. 1E, Table S1). The age of cells that don’t divide is the age of the donor plus the time in culture. For cells such as astrocytes that divide, the cell age is mixed based upon the number of cell divisions that occurred in the patient and subsequently in culture. Each single cells (Fig. 1D) RNA was aRNA amplified and deep sequenced. On average, we obtained approximately 22.5M uniquely mapping reads per sample of which approximately 60% exonic reads mapped to an average of 12,000 genes. When compared with publically available GTEX tissue transcriptome data, these single cell transcriptomes had the greatest overlap with the whole brain tissue samples of all brain cell types (Fig. S1).

Fig 1. Healthy long term adult human brain cell cultures.

(A-C) Representative healthy brain cells at 2, 4 and 8 weeks in culture, respectively. scale bar: 20μm. (D) Summary of patient information including age, gender, ethnicity, FMAID for biopsy location, and diagnosis (M-male, F-female, C-Caucasian, AA-African American, GBM-Glioblastoma, Pt. 85 also had samples harvested from the hippocampus in addition to the cortical FMAID listed). (E) Images of culture pre- (left) and post-harvest (right) of a single cell using micropipette aspiration. scale bar: 20μm (See also Fig S1)

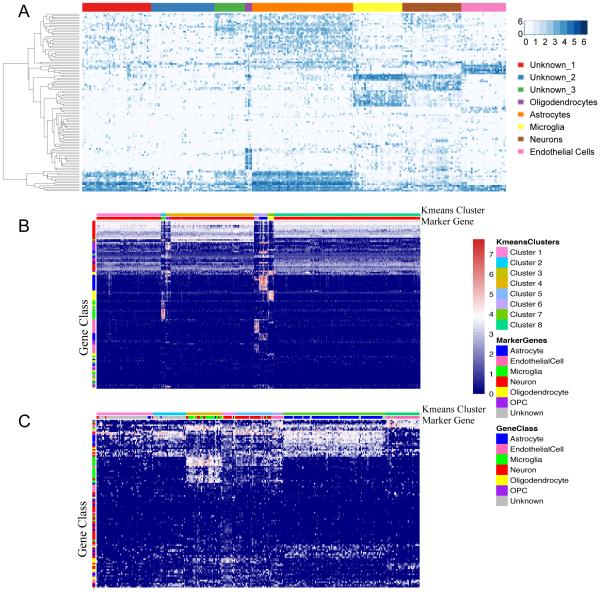

Marker and pathway based identification of human brain cell types

In order to identify cell classes from the transcriptome data we first clustered based upon cell-type marker expression. In our and other groups’ experiences, mouse cell type markers sometimes fail to provide strong discrimination of comparable human brain cell types (Darmanis et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2016). To obtain an initial classification, we used a list of 129 “marker genes” that have been used to successfully discriminate between multiple human brain cell types (Darmanis et al., 2015). In Fig 2, of the 303 adult human brain cells that met our quality standards, we used k-means clustering (k=8; see methods) to group 187 single cells into 5 classes (5-oligodendrocytes, 35-microglia, 42-neurons, 32-endothelial cells, 73-astrocytes) with the remainder of the cells falling into three unknown classes (49, 45, and 22 cells respectively, Fig. 2A, Table S1). Although many of these unknown cells share some gene expression patterns with astrocytes, they were unable to be confidently classified into the six cell type gene sets. Importantly, the presence of aged adult human cortical neurons in long-term primary cell culture stands in distinction to the mouse system where it has been difficult to perform primary culture of adult mouse cortical neurons.

Fig 2. Identification of cell types using human and cross-species markers.

(A) Using human cell type markers, cells fell into eight transcriptional groups representing oligodendrocytes, microglia, neurons, astrocytes, endothelial cells and unknown. (B) Mouse homologs of the human curated cell type marker gene list were used to cluster the ~1600 mouse cortical single cell transcriptomes reported in Tasic et al. showing strong concordance with the original papers groupings. (C) We used human homologs of 109 mouse genes described in the Tasic et al. to carry out the same k-means clustering showing concordance with our groupings but more varied expression and less defined expression patterns for each grouping.

To examine the effectiveness of human-curated gene lists for revealing mouse cell types, and vice-versa, we examined k-means clustering (k=8) of previously described mouse single cell data (Tasic et al., 2016). First, we used mouse homologs of a human curated gene list (Darmanis et al., 2015) to cluster the ~1600 mouse cortical single cell transcriptomes reported in Tasic et al. There is a high degree of concordance in the original paper’s cell type annotations and cluster membership using homologous human curated genes (Fig. 2B). We found overlap between the original cell type annotation and new clusters as follows: astrocytes, 100% in cluster 6; neurons 99.8% in cluster 4, 99.7% in cluster 1, and 99.2% in cluster 8; endothelial cells 74.7% in cluster 5, microglia 95.6% in cluster 2; and OPC 100% in cluster 7 and 71.4% in cluster 3. We also used human homologs of 109 mouse genes described by Tasic et al. to carry out the same k-means clustering on our data (Fig. 2C). These mouse markers successfully clustered many brain cell types; however, there were large groups of genes that were expressed in multiple clusters meaning they were not cell type specific in the human.

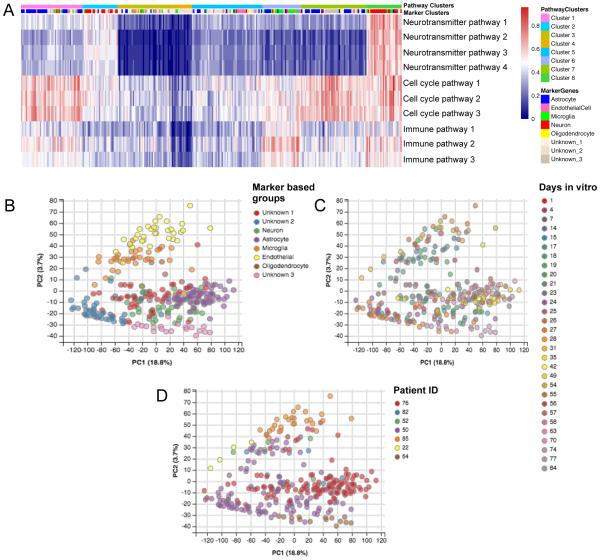

We next augmented the initial classification by assessing the activation of signaling pathways central to each putative cell type’s function. We curated a list of publically available pathway databases and scored each pathway’s activation levels. The pathways included four neurotransmitter release pathways to represent neuronal function, cell cycle pathways to represent dividing cells such as astrocytes, and immune response pathways to represent microglial function. K-means clustering (k=8) was performed on each pathway for all samples (Fig. 3A, Table S2). There was substantial overlap between the pathway clustering and the marker based cell type classifications. Astrocytes were the most common type in cluster 1 (55%) and cluster 7 (46%), cluster 4 was mostly cells from the unknown_2 cell type, while microglia were the most common type in cluster 6 (48%), and the neurons made up 71% of cluster 8 (Table S3). Endothelial cells and oligodendrocytes were spread over all of the clusters without a major dominant cluster assignment, as there were no suitably unique pathways for their functions in the pathway databases. Limits in the available curation of pathways in relation to specific cell function constrained the resolution of this analysis but neurons in marker gene analysis showed the highest degree of neurotransmitter pathway activation, microglial cells showed distinct immune pathway activation, and astrocytes showed the highest degree of cell-cycle pathway activation.

Fig 3. Pathway activity based and unsupervised clustering of data.

(A) K-means clustering of cells based on pathway activity (see Table S2 for exact pathway names) – top bar: pathway cluster, bottom bar: marker based cell type. (B) PCA analysis of the entire expressed (non-null) transcriptome showing clusters that correspond well with the cell types determined by k-means clustering using only human cell type marker genes. (C) Identical PCA analysis color-coded based on days in vitro (DIV) showing DIVs spread across clusters. (D) Identical PCA analysis color-coded based on patient source ID showing that although there is a primary patient representing the majority of points in each cell type, each cell type cluster does have multiple patients represented. (See also Fig S3)

We examined the dispersion patterns for the total transcriptome in contrast to the curated gene sets discussed (above). Fig 3 C-E show 2D PCA ordination of the whole transcriptome with covariates (Fig. 3B, cell type assignments by curated genes; Fig. 3C culture dates; Fig. 3D patient ID). Although cultures from some patients were enriched in a given cell type, each cell type was seen in multiple patients highlighting a cell type robustness that extends beyond a single patient’s mRNA signature. Additionally, although we were limited by sample availability, cells of varying DIV were represented in each patient and each cell type. Further, PC1 separation was not dominated by any of the covariates suggesting no dominant batch effects.

Stability of cell classification

We sought to characterize moderate to low abundance transcripts by high-depth sequencing. As it is more common to sequence single cell data to lower depth, we examined the impact of reducing sequencing coverage by creating randomly down sampled datasets of 1 million (M), 0.5 million, and 0.1 million reads (see Methods). The effects of down sampling depend upon the relative frequency distribution of the transcripts and therefore different cell types and gene classes maybe impacted differently. We examined the impact of number of of genes, segregated by marker defined cell type and gene classes (Fig. S3). Over all cell types and gene classes, down sampling resulted in a loss of ~52%, 60%, and 77% of the observed genes for 1M, 0.5M, and 0.1M sequencing depth. The greatest loss occurs for the neuron transcriptomes, with loss of ~63%, 77%, and 85%, respectively for 1M, 0.5M, and 0.1M sequencing depth; while the least loss is seen in the astrocyte cells with ~36%, 44%, and 65%, respectively for the same set of sequencing depths. For the different gene classes examined here (transcription factors, lncRNAs, pri-miRNAs and signal pathway genes), no particular class seemed more or less affected than the overall loss rate (other than transcription factors in neurons), suggesting that genes belonging to these classes are evenly distributed within the frequency distribution. Nevertheless, we note that at a low sequencing depth of 0.1M reads, we fail to see between ~55% to 88% of genes in transcription regulation pathways. Down sampling had negligible impact on classification by the PLDA function with less than 1% change in accuracy from the original full dataset for all cell types and all down-sampled treatments. This result is consistent with the idea that shallow depth sequencing can be useful for identification of major cell types although lower abundance genes critical to specific cellular function and specification will be missing. These data also highlight the fact that these cell classifications and some subclassifications could be documented with 100’s of cells as compared to the 1000’s of cells that have been reported elsewhere.

Classifying brain cells by morphology and non-coding RNA profiles

For each of the sequenced cells, we imaged the cell prior to harvest to capture its morphology. We estimated a morphological classification tree using six morphological features scored from the images taken prior to RNA collection: (1) gross cell size; (2) cell shape; (3) cell process; (4) process complexity; (5) cell margin; and (6) cytosol/nuclear ratio (Table S1). Multiple morphologies were observable for each cell type (Fig. 3). Maximum parsimony method was used (Swofford et al., 1996) and morphological trees were computed using the TBR heuristic search option in the program PAUP* (Swofford, 2003). We identified 31 distinct morphological groups where all cells within each group had the same constellation of morphological features (Fig. S2). The maximum parsimony tree split into two major branches, broadly separated into cells that were generally bigger with either simple or complex processes and cells that were generally smaller without processes. Cell boundary states or cytosol/nuclear ratio features did not co-vary with cell subclasses. Particular morphological features showed variable association with the transcriptional cell types. For example, there were putative astrocytes with both complex and simple processes (Fig. 3 A,B), putative microglia with cell bodies that were very similarly sized or much larger than their nuclei (Fig. 3 C,D), large and small putative neurons (Fig 3 E,F), and putative endothelial cells with and without processes (Fig. 3 G,H). As suggested by the representative images of the range of morphologies (Fig. 3), examining cell morphology within each transcriptional cell type showed variable distribution of morphological traits for many cell types. We found that the vast majority of astrocytes were both large (98%) and had processes (99%), endothelial cells were mostly large (86%) but only 45% had processes, 67% of microglia were large and 58% had processes, and 65% of neurons were large and 78% had processes. The oligodendrocytes were divided with regard to size and process presence but the small sample size in that class made it difficult to characterize (Table S1). To match the threshold used to select the cell type markers, we used 60-fold enrichment to identify genes associated with process bearing cells. These genes were significantly enriched in GO terms such as synapse, neuron projection, cell junction and axon (bonferroni corrected p=0.003, 0.004, 0.02, and 0.05 respectively) thus suggesting the possibility that higher expression of these genes either results from or is responsible for the presence of processes.

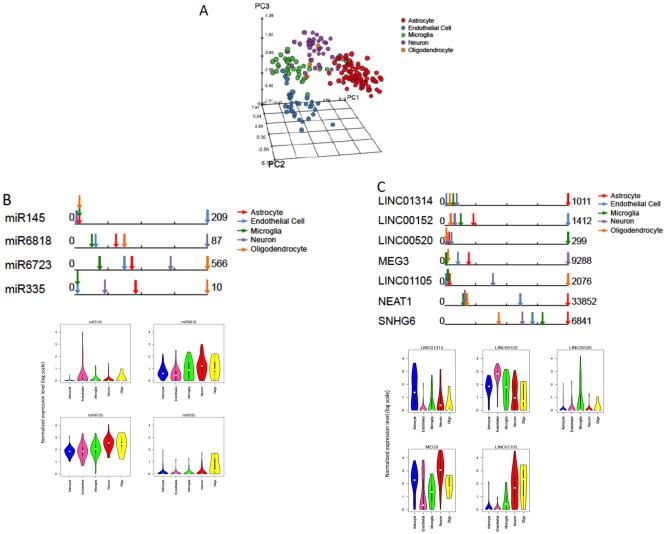

We next assessed non-coding RNA expression, lncRNA and pri-miRNA, as possible discriminators of cell types due to their role in simultaneously modulating multiple genes. Using a curated list of 935 lncRNAs (Amaral et al., 2011) to perform a k-means cluster analysis (k=8) of all of our samples, we found that there were lncRNA clusters, each strongly associated with marker-based cell types: cluster 2 with 69% endothelial cells, cluster 6 with 71% astrocytes, cluster 1 with 55% neurons, cluster 5 with 80% microglia, and cluster 8 with 80% oligodendrocytes (Fig. 4A, Table S1). A similar analysis of the 30 pri-miRNAs in our data showed that clusters found using only pri-miRNAs was generally disconcordant with marker gene based clusters, although there was one cluster with a high degree of overlap with microglia.

Fig 4. Range of cell morphology.

Astrocytes were observed with both complex (A) and simple processes (B), microglia had cell bodies that were very similarly sized (C) or much larger than their nuclei (D). We observed both large (E) and small (F) neurons and endothelial cells with (G) and without processes (H) scale bar: 20μm (See also Table S1 and Fig S2).

Cultured adult human brain cells lacked stem cell signatures

Although the cells analyzed were cultured from normal tissue harvested during the course of surgery, we wanted to evaluate the possible expression of proto-oncogene mRNA expression in the cells from the cancer patients (Vogelstein et al., 2013) to rule out the possibility that we had cultured oncogenic cells. We found enrichment of only 1 proto-oncogene (EGFR) in the cells from the cancer patients over those from epilepsy patients. In addition, the tumor suppressor p53 is also expressed at similar or elevated levels in these cells from patients across all diseases suggesting the normal anti-oncogenic function of p53 is intact in these cells. As many of these samples are sourced from patients with glioblastoma, we are cognizant of the phenomenon of brain cells de-differentiating to a stem cell nature during tumorigenesis indicated by a loss of mature cell type markers and the increased expression of Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc and Klf4 (Friedmann-Morvinski et al., 2012; Li et al., 2011). Expression levels of these genes across diseases in our sample set did not show broad expression of these markers except for Sox2 expression that was present across cells of all diseases and not restricted to gliobastoma samples. Furthermore, Sox2 is known to be expressed by astrocytes and is therefore alone not a good measure of stem-like phenotype (Xia and Zhu, 2015). There was 1 cell out of 300 that did have expression of the 4 stem-cell genes but it fell into one of the unknown cell type categories. This suggests that we are able to detect stem cells but that the vast majority of our cells are adult, mature and differentiated cells.

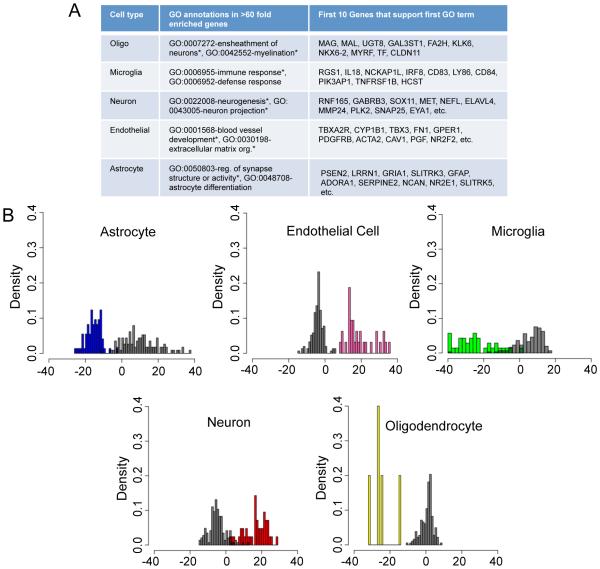

Cell-type enriched markers for human brain cells

Using our marker gene-based classification, we examined cell type-specific gene expression patterns to detect new markers. Again, to match the threshold used to identify cell type markers, we first identified genes that were enriched >60 fold in each cell type as compared to every other cell type in a pairwise fashion. This analysis produced hundreds of additional candidate cell type markers for human cells (Table S4). We performed a GO term enrichment analysis for these genes and found significant enrichment of immune response genes in microglia, neuron ensheathment annotations in oligodendrocytes, neurogenesis and projection development in neurons, blood vessel and extracellular matrix organization genes in endothelial cells, and astrocyte differentiation and synapse support genes in astrocytes (Fig. 5A).

Fig 5. Noncoding RNAs are enriched in cell types and can discriminate cell types.

(A) 3D PCA analysis of normalized lncRNA expression shows dispersion patterns that are generally consistent with marker based cell types. (B) Average normalized pri-miRNA expression in each cell type for significantly differentially expressed pri-miRNAs and the distribution of expression highlighted by the violin plot which shows the probability density for each pri-miRNA and (C) Normalized lncRNA expression levels highlighting lncRNAs enriched in a single cell type (first 5 lncRNAs), enriched in multiple cell types (NEAT1), and SNGH6 which is highly expressed in all cell types (See also Fig S5) and violin plot showing the probability density for each lnc RNA.

In addition to these individual genes, we used Penalized Linear Discriminant Analysis (PLDA) to find a weighted linear combination of genes that would have high utility for identifying each cell type (Witten and Tibshirani, 2011). We extracted discriminant axis for each cell type against every other cell type (Fig. 5B). The PLDA functions resulted in cross-validation (1:1) accuracy of 97%, 97%, 99%, 89%, and 99%, respectively for marker defined astrocytes, neurons, endothelial cells, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. The genes with large absolute value loading coefficients in the PLDA axis overlapped significantly with the original 129 marker genes (Table S5). The PLDA generated highly accurate classifiers using the whole transcriptome, with the penalization constraint to sparsely utilize the gene features. We examined the distribution of absolute value of the coefficient loadings for each cell type (Fig. S4), which showed that most of the information is concentrated within top 20 genes. It is desirable to reduce the feature set as much as possible, both to guard against over-fitting. Therefore, we constructed new PLDA classifiers based on top 20 genes for each cell type. Cross-validation (1:1) accuracy ranged from 94% to 99%, showing the utility of this reduced discriminant function (Table S6). We used the reduced PLDA function to analyze the cells in the three previously unknown clusters (Fig. 2A) and were able to assign identities to 45 of 116 unknown cell types (Table S7). We propose the PLDA functions will have utility for identification of human cell types and for deconvolving cell mixtures into single cell frequency counts (by expressing a tissue expression value as linear combinations of these discriminant axes).

Cell-type specific transcription factor binding sites, pri-miRNAs and lncRNAs in human brain cells

Using the genes enriched in each cell type, we asked if there was potentially shared control of the genes by cell-type specific transcription factor and/or miRNA binding motifs enriched in those genes using the ToppGene suite (Chen et al., 2009). Though there was some overlap between oligodendrocytes and neurons, every cell type had unique transcription factors that potentially controlled their enriched genes’ expression (Table S7). For example, oligodendrocyte enriched genes had enrichment in AP4 and MyoD (likely due to homology with OLIG1/2, (Hernandez and Casaccia, 2015)) transcription factor binding sites while many microglial genes have potential to be controlled by PEA3. Neuronal genes had enrichment of multiple transcription factor and miRNA biding sites.

The presence of pri-miRNAs in our transcriptome was expected as pri-miRNAs have poly-A tails that can be amplified in our procedure. We performed differential expression analysis to identify cell type-enriched pri-miRNAs (Fig. 4B). We found that MIR6723 is more highly expressed in neurons than in astrocytes, endothelial cells and microglia while MIR6818 is more highly expressed in neurons than in astrocytes and endothelial cells. MIR1199 and MIR335 are more highly expressed in oligodendrocytes than in any other cells. MIR145 is more highly expressed in the endothelial cells than astrocytes, microglia and neurons. It has been shown previously that endothelial cells express MIR145 for critical regulation of smooth muscle cells in the peripheral vasculature (Hergenreider et al., 2012). Our study suggests that endothelial cells in the brain also express MIR145, which targets genes related to adherens junction and tight junction pathways. MIR335, which is highly expressed in oligodendrocytes, targets genes related to neurotrophin signaling pathway (Vlachos et al., 2012).

To identify cell type-dependent long noncoding RNAs, we performed differential expression analysis on Lncs by cell type. Among 935 lncRNAs, 113 lncRNAs are differentially expressed across cell types (Figs. 5 and S5). There was a range of expression from strong single cell type enrichment (i.e. LINC01314-astrocytes, LINC00152-endothelial cells, LINC00520-microglia, MEG3-neurons, LINC01105-oligodendrocytes) to enrichment in a subset of cell types (i.e. NEAT1-high in astrocytes and endothelial cells) to shared expression across all cell types (i.e. SNHG6, Fig. 4C). Previously, Meg3 which we found to be enriched in neurons, has previously been found in GABAergic neurons (Mercer et al., 2010)..

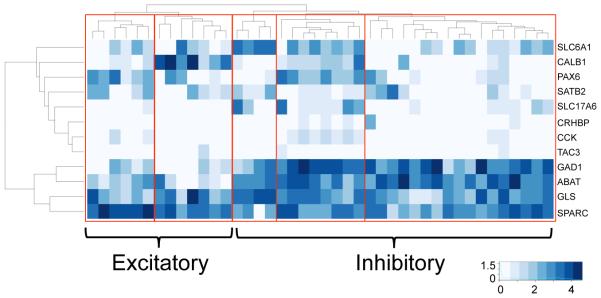

mRNA profiles predict neuronal subclasses

Some of the CNS cell types have well known subclasses. For example, neurons are often categorized as excitatory or inhibitory; other researchers have argued for seven to sixteen neuronal subtypes in human and at least 28 in mouse (Darmanis et al., 2015; Lake et al., 2016; Zeisel et al., 2015). In an attempt to subdivide the adult human neurons into finer subclasses, we used a curated list of possible excitatory or inhibitory markers (Darmanis et al., 2015; Fish et al., 2011; Takamori, 2006). Marker expression suggested a mixed biology with many cells expressing both excitatory and inhibitory markers, that has been observed previously in other species. We hierarchically clustered the neurons using this gene list and found that the cells fell into five clusters and many displayed the possibility of co-release of neurotransmitters (Fig. 6). Cluster 1 had relatively high expression of SPARC suggesting cells undergoing significant remodeling and neurite outgrowth. Cluster 2 had high expression of calbindin 1 (CALB1) and almost no expression of glutamate decarboxylase 1/2 (GAD1/2, often used markers of inhibitory neurons) suggesting that this cluster represents a group of CALB1+ excitatory neurons (Chard et al., 1995; Punnakkal et al., 2014). Groups 3 and 5, with their expression of GAD1, are likely both inhibitory although finer distinction was not obvious. Group 4 has mid-level expression for many excitatory and inhibitory linked genes although stronger expression of inhibitory markers highlighting an example of cells exhibiting co-release probability. These findings show the importance of single-cell resolution phenotyping of neuronal subclasses to accurately assess the range of unique possible cell types that may result in mixed neurobiology.

Fig 6. Cell type specific analysis.

(A) Summary of enrichment of GO terms for each cell type. * indicates GO terms significantly enriched <0.05 with bonferroni correction, others listed are <0.05 without correction (B) Histogram of PLDA score distribution for each of the five different cell types. The X-axis of each plot shows the PLDA scores while the histogram shows the scatter of the cells. Top colored panels show the cell type of interest while the black bar panels show the other cell types (See also Tables S4-8 and Fig S3).

Identification of patient-associated miRNAs and transcription factors

Though these cells were from multiple patients with varying diseases, disparate ages and whose cells were cultured for different lengths of time, there remained underlying patient-based transcriptional patterns that were shared between cells. By grouping the samples by patient, we identified a differentially expressed gene list defined as expressed >60 fold over at least 4 other patients and performed enrichment analysis for many factors using ToppGene (Chen et al., 2009). For example, there were 351 genes that were enriched in samples from patient 52 (Table S8) excluding those that were specifically linked to a cell type (as listed in Table S1). This gene set showed significant enrichment in being controlled by the ETS2, ELF1, and PEA3 transcription factors whereas a similar analysis of patient 64 showed regulation by a number of transcription factors including E2F, E2F1, and many others but also showed strong regulation by miRNAs (for example: 519a, 500, 24, 1284 and 29c, p<0.05 bonferroni corrected). Similar analyses were completed for all patients. They highlight a variety of shared and distinct control patterns of genes across patients including precursor miR expression. Interestingly, patients 64 and 85 share very little in common including exhibiting different diagnoses, genders, and ethnicities; however, both show enrichment of miR29 a, b and c binding sites in their enriched gene set suggesting that there is some other environmental or genetic commonality resulting in the need for similar regulation of miR29 regulated genes.

Single cell drug-induced transcriptome modifications

We also attempted to dissect the patterns of gene expression associated with patient drug treatment history. To identify these genes, we compared expression patterns within each drug-treated samples type to non-drug-treated samples using a recently developed Single Cell Differential Expression (SCDE) package (Kharchenko et al., 2014). Because of the inevitable uneven sampling of drug treatments between patients, many of the treatment factors were compounded and power for distinguishing effects was low. After correction for multiple testing, in endothelial cells we found association in Keppra and Dexamethasone treatment (compounded together) for the genes (adjusted p-value in parenthesis): GFAP (0.002), CD14(0.041), HTRA3 (0.041), PDPN (0.041). Other suggestive cell type/drug/gene differential test results are listed in Table S9. These data will benefit from additional patient samples from similarly drug treated individuals.

Discussion

Investigating human disease and cellular response to drug therapy is most appropriately performed in humans. Such experiments are most conveniently performed in a culture system for ease of access, solution perfusion, manipulation, and imaging. Until now, there has not been an adult human brain cell culturing system for such studies. Herein we report the ability to culture healthy adult primary brain cells for months. Although adult rodent brain cell cultures are difficult to generate, human brain cell cultures did not suffer the same attrition. The cells exhibited healthy morphologies and maintained strong cell type marker RNA expression, suggesting that these cells thrive as their true cell types not as a shadow of their original robustness. This system allows for the investigation of human disease and drug effects at the single cell level with the added capability of performing testing in a cell type specific manner.

In our desire to analyze single human brain cell transcriptomes and cellular variability in expression profiles, we have deep sequenced over 300 hundred single cells from adult human brain primary cell cultures enabling us to identify various cell types. Conventional wisdom would suggest that each type of cell has a set of known markers whose abundant presence consistently defines a cell phenotype (Redwine and Evans, 2002; Xu et al., 2010). Recent work in mice using Cre-mediated fluorescent tagging of marker positive cells, has begun to highlight the range of cell types in mice expressing each presumptively canonical cell-specific markers (Tasic et al., 2016). Similarly, our study has shown that adult human brain cells also exhibit non-celltype restricted expression of many such “canonical” markers however other RNAs can serve as appropriate markers. .

This cell type subgroup analysis led us to three conclusions. First, although we have samples from multiple ages, diseases, and drug treatments, we found that the cell type expression profiles were robust enough to stand out amongst this biological variation. Secondly, we have a better idea of the variability in gene expression that results in subclasses of cells in the human brain. For example, markers found using populations of cells would suggest a simplicity and almost bimodal (on/off) expression of these genes between cell types which is generally not observed for mRNA in the human system. Often marker genes derived from mouse studies are not highly expressed and are sometimes absent in human cells in the celltype they are presumed to define. A network of genes relevant to the cell’s function whose expression determines the cell’s fate including lncRNAs and pri-miRNAs, appears to be more relevant to cell identity, rather than the high expression of any one given mouse cell type derived “marker”. Lastly, in part by comparing expression patterns in our cultured cells to those harvested acutely from patient brains, we find that there is an resiliency to the cell type expression profiles (Darmanis et al., 2015) and in vivo morphology (Darmanis et al., 2015; Fields, 2013) that is maintained in our cultures that makes this system useful for studying primary oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells, astrocytes, microglia, and multiple classes of interneurons and excitatory neurons just to name a few.

Morphology alone was not the best differentiator of these human cultured cells. In rodents, by contrast, a trained researcher can easily differentiate between a neuron and astrocyte based on classical shapes. Expanding upon the recent findings (Zhang et al., 2016), we found that the morphology of cultured human astrocytes is less distinct and more complex than that of rodent cultured astrocytes. There seems to be a larger number of cell type associated morphologies than in rodent cultured cells possibly to meet the uniquely complex system demands on each cell in the human system. Just as our preconceived notions about marker gene expression based upon rodent studies are more complex in the human system, so too are the expected responsivities of human cells. The transcriptomes of adult human cells suggest a broader range of expression of surface channels and receptors than in the mouse with a likely broader range of functional responses to stimuli. This is predicted by the higher complexity of networks required to perform higher level functioning in humans.

In addition to morphological differences between human brain cells and those from lower species, the defining genes that are used as markers as well as those that drive that cell’s functional phenotype can be distinct. While mouse-derived oligodendrocyte markers were the most successful at distinguishing human oligodendrocytes from other cell types (high expression of ~60% of mouse oligodendrocytes markers in the majority of human oligodendrocytes), mouse-derived neuronal markers were less successful (high expression of ~3% of expressed mouse neuronal markers in the majority of human neurons (Cahoy et al., 2008)). This may in part be due to the greater genetic diversity of human patients in comparison to that of inbred mouse strains. These realities highlight the necessity of using human cells for human disease and drug studies.

In clustering these neurons into neuronal subtypes, we found that the expression profiles were more complex than expected. Interestingly, although cluster 1 in Fig 5 had the highest level of SPARC, all other neuronal clusters also expressed the gene suggesting a continual need and capacity for neural remodeling (Andres et al., 2011). Cluster 1’s low level expression of many genes is in line with the possibility that they are highly plastic cells able to adjust as the network needs require. We hypothesize that stem cells have a low level of expression of a wide range of genes allowing for more rapid differentiation into a mature cell as the need arises and these cells clusters exhibit this profile feature. Similarly, cluster 4’s mid-level expression of many genes suggests a progenitor cell classification while its strong expression of GAD1 and ABAT suggest that they are inhibitory. Together, this suggests a lack of full commitment to a single cell type perhaps enabling the plasticity of the human brain to be directed by specific microenvironmental signaling cues. Cluster 2’s high expression of calbindin 1 (CALB1) which is involved in synaptic plasticity in excitatory neurons (Chard et al., 1995) and near absence of GAD1 and GAD2, suggests that this group is excitatory although CALB1 has also been found in GABAergic neurons of the human cortex (del Rio and DeFelipe, 1996). Groups 3 and 5 have strong expression of inhibitory genes and low expression of many excitatory genes, suggesting that they are inhibitory neurons; however, there was a small but noticeable amount of expression of traditionally excitatory neuron linked genes highlighting the likelihood of cells that co-release multiple neurotransmitters.

This mixed expression again suggests the functional plasticity required by and built into the human nervous system. Some of these cell groups contrast to those observed by others (Darmanis et al., 2015), in which 5 communities of interneurons were composed of cells co-expressing PAX6/RELN, CPLX3/SPARC/SV2C, and a distinct group of PVALB+ cells among other distinctions. In our adult cells while we found that the majority of PVALB+ cells fell in a single class, it was the class that had low to mid level expression of many genes. We did not find a strong correlation between PAX6 and RELN although they were co-expressed in some cases or within the CPLX3/SPARC/SV2C gene combination. In fact, in contrast to SPARC, CPLX3 and SV2C had low and sporadic expression in our analysis. The transcriptional complexity we have observed has been functionally shown by others wherein neurons may not express single neurotransmitters, for example a neuron can express both glutamate and GABA and be responsible for both types of signaling. This co-expression of conventional excitatory and inhibitory markers is abundant in our adult cultured human neurons and suggests a dramatically altered cellular ipseity. The complexity of these data highlights how difficult it is to determine a finite number of transcription-based cellular subclasses that meaningfully exist, At the extreme each cell is a transcriptional and physiological “unicorn” exhibiting unique transcriptional profiles and physiological interactions with the transcriptome providing a “hypothesis as to presumptive cell function”. The cellular environment plays upon the cells transcriptome to produce cells of needed function hence the observed transcriptional plasticity.

Even with the variability of adult human neuronal cell transcriptomes that we describe there appears to be overriding cellular regulatory hierarchies with general cell type, such as neuron or endothelial cell, being consistent across patients and diseases while there is also a patient specific transcriptome that can define an overall patient expression pattern. As there are many distinguishable cell types this set of discriminators must exert their function on top of the patient specific discriminators. These transcriptional networks likely result from hierarchical epigenetic modification of cellular genomes highlighting the need for a robust single cell epigenomic platform.

Although our drug-effect analyses were underpowered, we were able to predict some long-lasting (6 weeks post-removal from on board patient drug therapy) drug-induced changes in cell type specific gene expression. This long-lasting effect suggests an epigenetic effect of these drugs upon the patient. With more patients-derived samples, this approach may prove to be informative in drug efficacy studies as well as in assessing potential adverse side effects. As such the techniques in this study are potentially useful as an approach to personalized precision medicine.

We have successfully cultured 6 major classes of brain cells, identified enriched RNAs in each class, found systems that likely control this gene enrichment, and have predicted alterations in gene expression that are the result of in vivo therapeutic interventions in multiple cell types. Further, it is clear that many RNAs should be designated as cell type selective rather than cell type specific as the marker will likely be greatly enriched in one cell type but also be expressed in other cell types in a non-defining manner. Primary culturing of adult brain cells from human biopsies has allowed us to capture the range of expression for each cell type and to glimpse the plasticity built into the human system. In addition to providing a model system to study human disease and drug treatments, these data have provided insight into the plasticity and range of phenotypes inherent in human brain cells that are necessary for the proper functioning of the human brain.

Experimental Procedures

Neurosurgery harvest

Adult human brain tissue was collected at the Hospital of University of Pennsylvania (IRB#816223) using standard operating procedures for enrollment and consent of patients,. Human brain tissue collection, handling, and de-identification of patient clinical data also followed standard operating procedures. The approximate region of cortex the specimen was collected from was identified using Brodmann area maps, which were then linked to the publically available Foundational Model of Anatomy ontology (http://bioportal.bioontology.org/ontologies/FMA) (see Fig 1A and Fig S1A). Using cortex or hippocampal tissue that was resected as part of a neurosurgical procedure for the treatment of epilepsy or brain tumors, we collected a 5x5x5mm block of tissue. This tissue was immediately transferred to a sterile container with ice-cold sucrose artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) solution (in mM: CaCl2-2H2O 2, glucose 10, KCl 3, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 2.5, MgCl2-6H2O 1, sucrose 202, with 5% CO2 and 95% O2 gas mixture) for transfer to the laboratory. Sucrose aCSF was oxygenated for at least an hour before the scheduled surgery to keep the brain tissue alive during transport. Tissues arrived in the laboratory ~10 minutes post excision.

Culturing

Brain tissue was digested using papain (20 U: Worthington), incubated for 10-15 minutes at 37°C, followed by Leupeptin (papain inhibitor, 100uM; Sigma Aldrich) to stop the reaction. After enzymatic dissociation, centrifugation (1500rpm for 3mins) followed by gentle mechanical dissociation was performed with a fire-polished glass pasteur pipet. The cells were counted in an Autocounter (Invitrogen) using trypan blue (1 %; Sigma Aldrich) to exclude dead cells. Cells were plated on poly-L-lysine (0.1 mg/ml; Sigma Aldrich) coated 12mm coverslips at a density of 3×104 per coverslip. Cultures were incubated at 37°C, 95 % humidity, and 5 % CO2 in medium (Neurobasal, B27-1%, Penicillin Streptomycin-1%; Thermo-Fisher). Media was changed by replacing 50% fresh media every three days.

Morphology

Images were taken before harvest and analyzed. Six features were scored: (1) gross cell size with three states, 0 = small, 1 = medium, and 2 = large; (2) cell shape with three states, 0 = radial and round, 1 = rod, 2 = radial and amorphous; (3) cell process with three states, 0 = no processes, 1 = uni-directional processes, and 2 = multi-directional processes; (4) process complexity with three states, 0 = no process, 1 = simple processes, 2 = complex processes; (5) cell margin with two states, 0 = smooth, 1 = rough; (6) cytosol/nuclear ratio with two states, 0 = small and 1 = large.

Amplification, library, sequencing, read processing

Single cells were harvested using a microcapillary pipette (Morris et al., 2011). Samples were snap frozen until processing. Three rounds of standard aRNA amplification were completed followed by Truseq stranded library generation as outlined by Illumina without the initial fragmentation step (Eberwine et al., 1992; Hashimshony et al., 2012). Samples were sequenced using either an Illumina Hiseq 2500 or Nextseq 500. After sequencing, reads were de-multiplexed with CASAVA software package, version 1.8.2 (Illumina, Inc). Reads were processed with the PennSCAP-T Pipeline (https://github.com/safisher/ngs). Sequence alignments were performed with STAR (Dobin et al., 2013). Exonic reads that uniquely mapped to the Genome Reference Consortium Human Reference 38 (GRCh38/Hg38) were processed with VERSE (BioRXiv) using a hierarchical assignment scheme and the GENCODE 21 transcriptome. Samples with greater than two million uniquely mapping reads and greater than 20% exonic mapping were included in analysis. Reads were normalized for differences in sequencing depth across samples prior to all further analyses by scaling raw read counts by sample-specific size factors as estimated in DESeq (Anders and Huber, 2010).

ComputationalAnalysis

GTEX

Similarity in gene expression between single cells in this study and multiple tissues in the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) dataset (GTEx Consortium, 2013), a large-scale public resource for human gene expression across tissues, was performed by digitizing the read counts of top-ranked highly expressed genes for each cell in this study according to several threshold (from 0 to 500, interval 10). We calculated median across samples within each tissue and digitized the read counts of top genes based on the median. We computed Jaccard similarity coefficient of the digitized read counts between each single cell and each tissue.

PCA

Principal component analysis was performed using the R package inside of IDV (http://kim.bio.upenn.edu/software/idv.shtml). Clustering was performed on the full transcriptome excluding genes with zero expression in all cells to eliminate clustering based on null-expression. The plot was then color coded to show the covariates for each comparison (marker based cell type, DIV, patient ID).

K-Means

K-means clustering of markers, pri-miRNAs, and lncRNAs was performed using the R package inside of IDV (http://kim.bio.upenn.edu/software/idv.shtml). To assess the appropriate number of clusters for the k-means algorithm, we carried out 2-fold and 5-fold cross validation experiments. For k = 2 to 15. For each cross validation experiment, we randomly split the data into training and test and computed the k-means centroids on the training data. The test data membership was fit to the closest centroid from the training data and the sum within cluster distance of the test data was defined as prediction error. Randomized cross validation experiments were repeated 10 times for each k. Fig X.1 and X.2 shows the prediction error and its standard error as a function of k. We established an elbow in the reduction of prediction error between k = 6 and k = 8 (cf., (Miligan, 1985)). We expected seven different types of cells (excitatory neurons, inhibitory neurons, astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, oligodendrocytes precursor cells, and endothelial cells). To allow for additional cell types, we chose k = 8 as for the cluster model choice. To identify the best k-means clusters, we tuned nstart option of kmeans function in R package (nstart=1000).

Gene annotations

The list of lncRNAs was the union of the human lncRNAs found in the lncRNA database (Amaral et al., 2011) and genes beginning with “LINC” annotated in gencode.v21 as Level-1,2 exons. Significant enrichment of miRNA and transcription factor binding sites in the enriched genes for each patient and cell type was determined using the ToppGene suite (Chen et al., 2009). Significant enrichment of GO terms in genes enriched in each cell class was determined using the GO Enrichment Analysis Suite as curated by the Gene Ontology Consortium (Gene Ontology Consortium, 2015).

Pathway analysis

To find pathway-derived subgroups, we used neuron-related functions, immune-related functions, cell cycle and signaling-related pathways from Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) v5.1 (Liberzon et al., 2011). We focused on curated pathway gene sets from online pathway databases such as BioCarta, KEGG and Reactome. Pathway activity is defined as the percentage of genes with >10 normalized reads in a pathway. The k-means method was used for clustering pathway activity in order to identify pathway-dependent cell types.

PLDA expression analysis

We identified the genes that best discriminate between each cell type and other cell types, using penalized linear discriminant analysis (LDA) (Witten and Tibshirani, 2011). The penalized LDA is a classification technique that by adopting sparsity constraints achieves feature selection. When the standard estimate for the within-class covariance matrix is singular, the usual discriminant rule cannot be applied. By considering L1 and fused lasso penalties on the discriminant vectors, we can solve the problem efficiently. In this study, the penalized LDA was implemented in the R package ‘penalizedLDA’. The lasso penalty tuning parameter lambda = 1e-04 was used from several trials, and the number of discriminant vectors was equal to the number of classes minus 1, since it must be no greater than the number (classes - 1).

Random sampling and sequencing depth

To assess the effect of a reduced sequencing depth, we used "sample" (https://travis-ci.org/alexpreynolds/sample), a function based on the algorithm developed by Jeffrey S. Vitter (Vitter, 1985) that randomly samples read pairs from a SAM file. We generated a series of down-sampled data sets where a subset of 1 million, 0.5 million, 0.1 million mapped reads were randomly sampled from the original data set in this study, repeating 25 times for each down-sampled level. To see how many genes are expressed in the original data and down-sampled data sets, we compared the number of detected genes between the sets. Detected genes are defined as genes with raw read > 0 in at least 70% of samples for each cell type. To examine whether reduced sequencing depth affects prediction accuracy, we applied the PLDA function generated by the original data set to the down-sampled data set.

Differential expression

For differential expression analysis of pri-miRNA and lncRNAs, we carried out one-way ANOVA using cell type as a factor. For multiple corrections, we applied the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Morphology analysis

For morphology grouping and covariance analysis, cell size, cell process, and process complexity were treated as ordered states while remaining features were treated as unordered states. Cells with identical feature scores were grouped as a single unit, resulting in a total of 31 morphologically distinct groups. Morphological trees were computed with the maximum parsimony method (Swofford et al., 1996) using the TBR heuristic search option in the program PAUP* (Swofford, 2003).

Drug-mediated differential expression

Single cell differential expression (SCDE) analysis was used to find differences in mean gene expression between drug-treated cells and drug-untreated cells. Cells were given a specific cell type using the Benjamini-Hochberg method for multiple testing correction (Kharchenko et al., 2014).

Supplementary Material

Fig 7. Multiple excitatory and inhibitory neuronal subtypes.

Heatmap of neuronal gene expression with hierarchical clustering of cells based on expression of canonical excitatory and inhibitory marker genes. Red boxes highlight distinct expression patterns of critical genes. (left to right) 2 excitatory and 3 inhibitory neuronal clusters are clear based on expression of GAD1 and patterns of other critical neuronal genes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Moorwood for processing some of the single cell samples, Jamie Shallcross for running the analysis pipeline, and our clinical research coordinators: Tim Prior, Kelsey Nawalinski, Katherine Murphy, and Eileen Maloney. This study was supported by the NIH Single Cell Analysis Program U01 MH098953.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions

JMS processed samples and did preliminary data analysis. YJN performed advanced data analysis. JL and JYS developed the culture protocol and JL generated cultures, imaged and harvested cells. TJB, MPG, JW amplified the samples and made libraries. HD, SAF, and MK provided assistance with analysis. GHB, SB, HIC, DKK, THL DMO performed surgeries. MSG performed surgeries and recruited patients. AVU and JAW developed SOPs for enrollment/consent of patients/live tissue transport, recruited patients, maintained de-identified patient database, and performed tissue dissociation. DS processed samples and performed sequencing. TB provided expertise on drug effects. JMS, JYS, YJN, JK, JHE planned experiments and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

Accession Numbers

The accession number for the RNA-seq data reported in this paper is dbGaP: phs000833.v5.p1.

References

- Amaral PP, Clark MB, Gascoigne DK, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. lncRNAdb: a reference database for long noncoding RNAs. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39:D146–151. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anders S, Huber W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome biology. 2010;11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres RH, Horie N, Slikker W, Keren-Gill H, Zhan K, Sun G, Manley NC, Pereira MP, Sheikh LA, McMillan EL, et al. Human neural stem cells enhance structural plasticity and axonal transport in the ischaemic brain. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2011;134:1777–1789. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS, Xing Y, Lubischer JL, Krieg PA, Krupenko SA, et al. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chard PS, Jordan J, Marcuccilli CJ, Miller RJ, Leiden JM, Roos RP, Ghadge GD. Regulation of excitatory transmission at hippocampal synapses by calbindin D28k. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:5144–5148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Bardes EE, Aronow BJ, Jegga AG. ToppGene Suite for gene list enrichment analysis and candidate gene prioritization. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37:305–311. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Tran S, Sigler A, Murphy TH. Automated and quantitative image analysis of ischemic dendritic blebbing using in vivo 2-photon microscopy data. Journal of neuroscience methods. 2011;195:222–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darmanis S, Sloan SA, Zhang Y, Enge M, Caneda C, Shuer LM, Hayden Gephart MG, Barres BA, Quake SR. A survey of human brain transcriptome diversity at the single cell level. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112:7285–7290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1507125112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Rio MR, DeFelipe J. Colocalization of calbindin D-28k, calretinin, and GABA immunoreactivities in neurons of the human temporal cortex. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1996;369:472–482. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960603)369:3<472::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dueck H, Khaladkar M, Kim TK, Spaethling JM, Francis C, Suresh S, Fisher SA, Seale P, Beck SG, Bartfai T, et al. Deep sequencing reveals cell-type-specific patterns of single-cell transcriptome variation. Genome biology. 2015;16:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0683-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberwine J, Yeh H, Miyashiro K, Cao Y, Nair S, Finnell R, Zettel M, Coleman P. Analysis of gene expression in single live neurons. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:3010–3014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields RD. Neuroscience: Map the other brain. Nature. 2013;501:25–27. doi: 10.1038/501025a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish KN, Sweet RA, Lewis DA. Differential distribution of proteins regulating GABA synthesis and reuptake in axon boutons of subpopulations of cortical interneurons. Cerebral cortex. 2011;21:2450–2460. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann-Morvinski D, Bushong EA, Ke E, Soda Y, Marumoto T, Singer O, Ellisman MH, Verma IM. Dedifferentiation of neurons and astrocytes by oncogenes can induce gliomas in mice. Science. 2012;338:1080–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.1226929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gene Ontology Consortium Gene Ontology Consortium: going forward. Nucleic acids research. 2015;43:1049–1056. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GTEx Consortium The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nature genetics. 2013;45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimshony T, Wagner F, Sher N, Yanai I. CEL-Seq: single-cell RNA-Seq by multiplexed linear amplification. Cell reports. 2012;2:666–673. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawrylycz M, Miller JA, Menon V, Feng D, Dolbeare T, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Jegga AG, Aronow BJ, Lee CK, Bernard A, et al. Canonical genetic signatures of the adult human brain. Nature neuroscience. 2015;18:1832–1844. doi: 10.1038/nn.4171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hergenreider E, Heydt S, Treguer K, Boettger T, Horrevoets AJ, Zeiher AM, Scheffer MP, Frangakis AS, Yin X, Mayr M, et al. Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:249–256. doi: 10.1038/ncb2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez M, Casaccia P. Interplay between transcriptional control and chromatin regulation in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Glia. 2015;63:1357–1375. doi: 10.1002/glia.22818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharchenko PV, Silberstein L, Scadden DT. Bayesian approach to single-cell differential expression analysis. Nature methods. 2014;11:740–742. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake BB, Ai R, Kaeser GE, Salathia NS, Yung YC, Liu R, Wildberg A, Gao D, Fung HL, Chen S, et al. Neuronal subtypes and diversity revealed by single-nucleus RNA sequencing of the human brain. Science. 2016;352:1586–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Li A, Glas M, Lal B, Ying M, Sang Y, Xia S, Trageser D, Guerrero-Cazares H, Eberhart CG, et al. c-Met signaling induces a reprogramming network and supports the glioblastoma stem-like phenotype. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:9951–9956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016912108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberzon A, Subramanian A, Pinchback R, Thorvaldsdottir H, Tamayo P, Mesirov JP. Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) 3.0. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:1739–1740. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer TR, Qureshi IA, Gokhan S, Dinger ME, Li G, Mattick JS, Mehler MF. Long noncoding RNAs in neuronal-glial fate specification and oligodendrocyte lineage maturation. BMC neuroscience. 2010;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miligan GW, Cooper MC. An examination of procedures for determining the number of clusters in a data set. Psychometrika. 1985;50:159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Miyashiro K, Dichter M, Eberwine J. On the nature and differential distribution of mRNAs in hippocampal neurites: implications for neuronal functioning. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:10800–10804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.23.10800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J, Singh JM, Eberwine JH. Transcriptome analysis of single cells. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redwine JM, Evans CF. Markers of central nervous system glia and neurons in vivo during normal and pathological conditions. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2002;265:119–140. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-09525-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. PAUP* Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) Version 4.0b10 for UNIX. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL, Olsen GJ, Waddell PJ, Hillis DM. Phylogenetic inference. In: Hillis DM, Moritz C, Mable BK, editors. Molecular Systematics. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland: 1996. pp. 407–514. [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S. VGLUTs: 'exciting' times for glutamatergic research? Neuroscience research. 2006;55:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasic B, Menon V, Nguyen TN, Kim TK, Jarsky T, Yao Z, Levi B, Gray LT, Sorensen SA, Dolbeare T, et al. Adult mouse cortical cell taxonomy revealed by single cell transcriptomics. Nature neuroscience. 2016;19:335–346. doi: 10.1038/nn.4216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachos IS, Kostoulas N, Vergoulis T, Georgakilas G, Reczko M, Maragkakis M, Paraskevopoulou MD, Prionidis K, Dalamagas T, Hatzigeorgiou AG. DIANA miRPath v.2.0: investigating the combinatorial effect of microRNAs in pathways. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:498–504. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr., Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339:1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten DM, Tibshirani R. Penalized classification using Fisher's linear discriminant. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B, Statistical methodology. 2011;73:753–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2011.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia M, Zhu Y. The regulation of Sox2 and Sox9 stimulated by ATP in spinal cord astrocytes. Journal of molecular neuroscience : MN. 2015;55:131–140. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0393-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel A, Munoz-Manchado AB, Codeluppi S, Lonnerberg P, La Manno G, Jureus A, Marques S, Munguba H, He L, Betsholtz C, et al. Brain structure. Cell types in the mouse cortex and hippocampus revealed by single-cell RNA-seq. Science. 2015;347:1138–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Pak C, Han Y, Ahlenius H, Zhang Z, Chanda S, Marro S, Patzke C, Acuna C, Covy J, et al. Rapid single-step induction of functional neurons from human pluripotent stem cells. Neuron. 2013;78:785–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, Caneda C, Plaza CA, Blumenthal PD, Vogel H, Steinberg GK, Edwards MS, Li G, et al. Purification and Characterization of Progenitor and Mature Human Astrocytes Reveals Transcriptional and Functional Differences with Mouse. Neuron. 2016;89:37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.