Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate the effects of intravenous ketorolac on early postoperative pain in patients with mandibular fractures, who underwent surgical repair.

Methods:

This prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted in Shahid Rajaei Hospital, affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences during a 1-year period from 2015 to 2016. We included a total number of 50 patients with traumatic mandibular fractures who underwent surgical repair. Patients with obvious contraindications to ketorolac such as asthma, renal dysfunction, peptic ulceration, bleeding disorders, cardiovascular disease, mental retardation, or allergy to ketorolac or NSAIDS, were excluded. The patients were randomly assigned to receive intravenous ketorolac (30 mg) at the end of operation in post anesthesia care unit immediately upon the onset of pain (n=25), or intravenous distilled water as placebo (n=25). Postoperative monitoring included non-invasive arterial blood pressure, ECG, and peripheral oxygen saturation. The postoperative pain was evaluated by a nurse using visual analog scale (VAS) (0–100 mm) pain score 4 hours after surgery and was compared between the two study groups.

Results:

Overall we included 50 patients (25 per group) in the current study. The baseline characteristics including age, gender, weight, operation duration, anesthesia duration and type of surgical procedure were comparable between two study groups. Those who received placebo had significantly higher requirements for analgesic use compared to ketorolac group (72% vs. 28%; p=0.002). Ketorolac significantly reduced the pain intensity 30-min after the operation (p<0.001). There were no significant side effects associated with ketorolac.

Conclusion:

Intravenous single-dose ketorolac is a safe and effective analgesic agent for the short-term management of mild to moderate acute postoperative pain in mandibular fracture surgery and can be used as an alternative to opioids.

Key Words: Ketorolac, Postoperative pain, Mandibular Fracture, Surgery, Analgesic

Introduction

Maxillofacial injury occurs in approximately 5-33% of patients experiencing severe trauma [1]. Injuries to the maxillofacial region may be particularly debilitating. It is the region of specialized functions such as vision, hearing, olfaction, respiration, mastication and speech. Important vascular and neural structures which are intimately associated are present in this region and the psychological impact of disfigurement may also add to the level of resulting morbidity [2]. The prevalence of mandible fractures was more prevalent in male patients, especially during the 3rd decade of their lives. The most common cause was road traffic accident and the more frequently affected region was condyle of the mandible [3,4]. Inadequate postoperative pain relief may delay recovery, lead to a prolonged hospital stay, and increased medical costs [5]. Ketorolac is an injectable non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (non-selective cyclooxygenase inhibitor), blocks cyclooxygenase in the arachidonic acid cascade, thereby inhibiting the formation of prostaglandins with strong analgesic activity. When the ketorolac is administered intravenously, the initial analgesic response occurs within 30 minutes, and the time interval before which the peak of concentration is reached is 1 to 2 hours [6]. The onset of ketorolac analgesia is much slower than the onset of opioid analgesia. Compared with opioids, ketorolac 30 mg exhibited analgesic activity and pain relief equivalent to that of meperidine 50 mg and 100 mg intramuscularly and may be more cost-effective than intravenous morphine [7-9]. Previous studies investigated the administration of ketorolac wide acceptance in the treatment of postoperative pain in a variety of surgical procedures. It reduces opioid consumption by 25 to 45 percent and thereby lowers opioid-related side effects such as ileus, nausea, vomiting and shorter stay in hospital [5,10,11]. Ketorolac is used for moderate pain relief; and it may be used to treat severe pains when combined with opioids, reducing the opioid dose [12,13]. The adverse effects of ketorolac are gastrointestinal disturbances and renal impairment; however, the reported incidence is low and clinically insignificant [6]. We postulated that single dose administration of ketorolac in patients undergoing maxillofacial surgeries will significantly reduce the postoperative pain. Thus, the aim of this study was to determine the effects of intravenous ketorolac during the immediate postoperative period on postoperative pain in patients undergoing mandibular fracture surgery.

Materials and Methods

Study population

This randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial was carried out from March 2015 to April 2016, in Shahid Rajaei Hospital, affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. Institutional review board (IRB) and medical ethics committee approvals were obtained from the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.REC.1394.55). The trial was registered with Iranian registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT201607271674N13).The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, October 2008 (49th General Assembly of the World Medical Association). Written informed consents were obtained from eligible patients or by their legally authorized representative. We include those with mandibular fracture who were candidate for surgery under general anesthesia in the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. All the included patients were ASA I and aged between 16 and 47 years. Patients were included if they had no systemic diseases and no history of any drug consumption. Patients with a previous history of allergy to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, asthma, ischemic heart disease, renal failure and those who did not sign the informed consent were excluded from the study.

Randomization and Intervention

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio using a computer-generated table of random numbers. According to this table, numbers between 0 and 4 were allocated to the placebo and numbers between 5 and 9 were allocated to ketorolac groups. The first group of patients was given 30 mg of intravenous Ketorolac (C.T. Pharma, Rasht, Iran) at the end of the operation in post anesthesia care unit (PACU) immediately upon the onset of pain (n=25). The second group of patients was given intravenous placebo (1cc distilled water) immediately upon the onset of pain. The drug was administered by a nurse who was blind toward the study groups. The patients were also blind toward the drug they were receiving.

Anesthesia protocol

The general anesthesia method was similar for all patients. Intravenous 0.1 mg/kg morphine was administered to induce anesthesia. Induction was achieved with 2.5 mg/kg of propofol, 3 µg/kg of fentanyl, and 0.5 mg/kg of atracurium. Maintenance of anesthesia was achieved by infusion of 100 µg/kg/min propofol and 0.1 µg/kg/min remifentanil. All patients were monitored intraoperatively for heart rate, continuous ECG, non-invasive blood pressure (NIBP), and peripheral oxygen saturation by pulse-oximeter.

Outcome measurement

The nurses who recorded the data of pain and drug complications were blind regarding the grouping. The difference in postoperative pain between pretreated and post-treated side in each patient was assessed by three primary end-points: pain intensity as measured by a 100-mm visual analogue scale for 4 hours, time to rescue analgesic, postoperative analgesic consumption. Secondary endpoint included incidence of any adverse events of ketorolac in the recovery room. Pain intensity at rest was measured at selected intervals with a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS; 0 - no pain to 100 - worst possible pain). The pain severity was assessed by a blind operator every 5 minutes until 30 min, 1, 2, and 4 hours postoperatively. Rescue analgesia was administered at VAS≥40 mm, in the form of intravenous pethidine 1 mg/kg. All the patients were monitored in the post-anesthesia recovery room for the first 4 hours (every 5 minutes until 30 min, 1, 2, and 4 hours postoperatively regarding heart rate, non-invasive blood pressure, and pulse oximetry. Adverse events and postoperative complications were recorded throughout the study period.

Statistical Analysis

To estimate the required sample size, a pilot study was conducted by measuring VAS after surgery on 10 patients receiving intravenous ketorolac or distilled water. The VAS scores 4 hours after surgery in Groups "Placebo" and “Ketorolac" were 43.1±14.9 and 20.0±10.1, respectively. We aimed to demonstrate a difference of 100 mm in the VAS pain score 2 hours after surgery between the groups. With a two-tailed α=0.05 and a power of 80%, 24 patients needed in each group. Considering a loss to follow up rate of 10%, we entered 55 patients in the study. Descriptive analyses were performed on all baseline variables including means and standard deviations, medians, frequency and percentages, as appropriate. Independent t-test was used for comparing parametric variables and chi-square test for proportions between groups. To compare baseline pain score and time to onset analgesia, Mann-Whitney test was used. In addition, Wilcoxon signed Ranks was used for the comparison of pain score before and after of ketorolac administration. Statistical analysis was performed by statistical package for social sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) version 17. A 2-sided p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

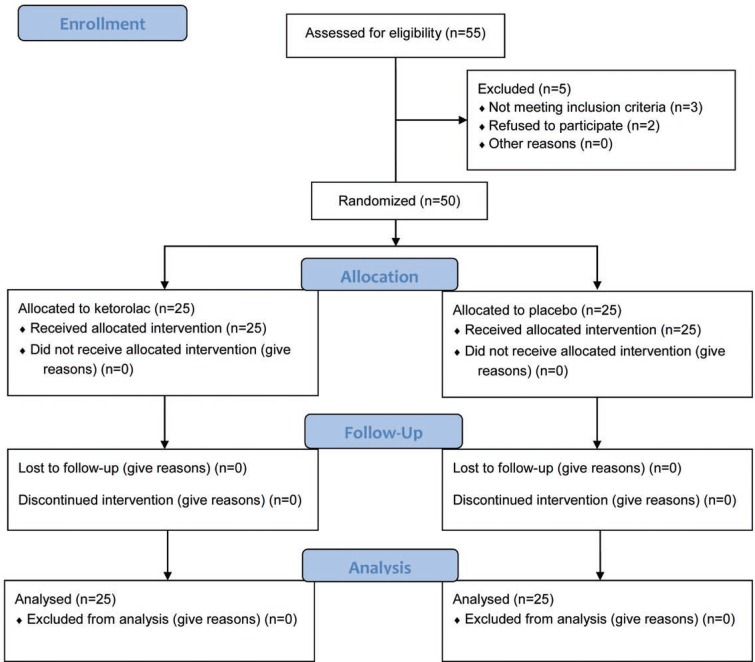

A total of 55 patients were eligible to enter the study, of whom 2 patients refused to participate in the study and 3 did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 50 patients that signed consent forms (consisting of control group, 25; and experimental group, 25). No patient was lost from the study due to adverse events or study complications (Figure 1). The results showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups regarding age (p=0.155) and sex (p=0.999). The baseline characteristics of the patients in two study groups are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram of the study

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 50 patients with mandibular fractures undergoing surgery in two study groups

| Ketorolac (n=25) | Placebo (n=25) | p - value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 29.64 ± 8.225 | 26.40 ± 7.599 | 0.155 |

| Sex | |||

| Men (%) | 15 (60%) | 15 (60%) | 0.999 |

| Women (%) | 10 (40%) | 10 (40%) | |

| BMI | 21.46±3.07 | 21.30±2.55 | 0.840 |

| Operation duration (hr) | 2.56±0.939 | 1.94±0.666 | 0.010 |

Those who receive ketorolac had significantly shorter time to perceptible pain relief and onset of analgesia activity when compared to controls (p<0.001). The severity of baseline pain (the pain before intervention) was comparable between two study groups (p=0.999). The pain intensity did not decreased significantly within 30 minutes in placebo group while it decreased significantly in those who received ketorolac (p<0.001). The occurrence of VAS score >1 (need for treatment) evaluated serially from the recovery room did not reveal any significant difference between the ketorolac and placebo groups within 1 hour (p=0.490), 2 hours (p=0.999) and 4 hours postoperatively (p=0.725) (Table 2). The need for rescue analgesic within 1 hour after surgery was significantly lower in those who received ketorolac when compared to placebo (28% vs. 72%; p=0.002). However two study group were comparable regarding rescue analgesic after 4 hours (16% vs. 24%; p=0.480). There were no identifiable postoperative complications associated with the use of ketorolac. The study outcomes are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparing the study outcomes in 50 patients with mandibular fractures undergoing surgery in two study groups

| Ketorolac (n=25) | Placebo (n=25) | p - value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to onset of analgesia (min) | 18.8 ± 6.65 | 30 ± 1.85 | ˂0.001 |

| Pain intensity | |||

| Baseline | 2.76 ± 0.87 | 2.72 ± 0.73 | 0.999 |

| 1 hour | 0.40±0.50 | 0.52±0.65 | 0.131 |

| 2 hours | 0.96±0.54 | 0.69±0.68 | 0.108 |

| 4 hours | 1.08±0.49 | 1.04±0.68 | 0.135 |

| VAS a >1 | |||

| 1 hour | 0 (0%) | 2 (8%) | 0.490 |

| 2 hours | 3 (12%) | 3 (12%) | 0.999 |

| 4 hours | 4 (16%) | 6 (24%) | 0.725 |

| Analgesic requirement | |||

| 1 hour | 7 (28%) | 18 (72%) | 0.002 |

| 4 hours | 4 (16%) | 6 (24%) | 0.480 |

VAS: Visual Analogue Scale

Conflict of interest:

None Declared.

References

- 1.Shahim FN, Cameron P, McNeil JJ. Maxillofacial trauma in major trauma patients. Aust Dent J. 2006;51(3):225–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2006.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghodke MH, Bhoyar SC, Shah SV. Prevalence of mandibular fractures reported at Dental College, aurangabad from february 2008 to september 2009. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2013;3(2):51–8. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.122428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodisson D, MacFarlane M, Snape L, Darwish B. Head injury and associated maxillofacial injuries. N Z Med J. 2004;117(1201):U1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poorian B, Bemanali M, Chavoshinejad M. Evaluation of Sensorimotor Nerve Damage in Patients with Maxillofacial Trauma; a Single Center Experience. Bull Emerg Trauma. 2016;4(2):88–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oderda GM, Said Q, Evans RS, Stoddard GJ, Lloyd J, Jackson K, et al. Opioid-related adverse drug events in surgical hospitalizations: impact on costs and length of stay. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(3):400–6. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinha VR, Kumar RV, Singh G. Ketorolac tromethamine formulations: an overview. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2009;6(9):961–75. doi: 10.1517/17425240903116006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fricke JR, Angelocci D, Fox K, McHugh D, Bynum L, Yee JP. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of ketorolac and meperidine in the relief of dental pain. J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;32(4):376–84. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1992.tb03850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith LA, Carroll D, Edwards JE, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single-dose ketorolac and pethidine in acute postoperative pain: systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84(1):48–58. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bja.a013381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rainer TH, Jacobs P, Ng YC, Cheung NK, Tam M, Lam PK, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of intravenous ketorolac and morphine for treating pain after limb injury: double blind randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2000;321(7271):1247–51. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7271.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulo A, van de Velde M, van Calsteren K, Smits A, de Hoon J, Verbesselt R, et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous ketorolac following caesarean delivery. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2012;21(4):334–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Oliveira GS, Agarwal D, Benzon HT. Perioperative single dose ketorolac to prevent postoperative pain: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(2):424–33. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182334d68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhiu S, Chung SA, Kim WK, Chang JH, Bae SJ, Lee JB. The efficacy of intravenous ketorolac for pain relief in single-stage adjustable strabismus surgery: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Eye (Lond) 2011;25(2):154–60. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carney DE, Nicolette LA, Ratner MH, Minerd A, Baesl TJ. Ketorolac reduces postoperative narcotic requirements. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(1):76–9. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.20011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gandhi K, Heitz JW, Viscusi ER. Challenges in acute pain management. Anesthesiol Clin. 2011;29(2):291–309. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Argoff CE. Recent management advances in acute postoperative pain. Pain Pract. 2014;14(5):477–87. doi: 10.1111/papr.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White PF, Raeder J, Kehlet H. Ketorolac: its role as part of a multimodal analgesic regimen. Anesth Analg. 2012;114(2):250–4. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31823cd524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bugada D, Lavand'homme P, Ambrosoli AL, Klersy C, Braschi A, Fanelli G, et al. Effect of postoperative analgesia on acute and persistent postherniotomy pain: a randomized study. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27(8):658–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rastogi B, Singh V, Gupta K, Jain M, Singh M, Singh I. Postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic cholecystectomy by preemptive use of intravenous paracetamol or ketorolac: A comparative study. Indian Journal of Pain. 2016;30(1) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Miranda N, Diaz A, Silva C, Morales O. Comparison of morphine, ketorolac, and their combination for postoperative pain: results from a large, randomized, double-blind trial. Anesthesiology. 2005;103(6):1225–32. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200512000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reinhart DI. Minimising the adverse effects of ketorolac. Drug Saf. 2000;22(6):487–97. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200022060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]