Abstract

Background & Aims

Reported global incidence and prevalence values for achalasia vary widely, from 0.03 to 1.63/100,000 persons per year and from 1.8 to 12.6/100,000 persons per year, respectively. This study aimed to reconcile these low values with findings from a major referral center, in central Chicago (which has been utilizing high-resolution manometry since 2004 and for all clinical studies since 2005), and have determined the incidence and prevalence of achalasia to be much greater.

Methods

We collected data from the Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse (NMEDW) database (tertiary care setting) of adults residing in Chicago with an encounter diagnosis of achalasia from 2004 through 2014. Patient files were reviewed to confirm diagnosis and residential address. US Census Bureau population data were used as the population denominator. We assumed that we encountered every incident case in the city to calculate incidence and prevalence estimates. Data were analyzed for the city at large and for the 13 zip codes surrounding the Northwestern Memorial Hospital (NMH), the NMH neighborhood.

Results

We identified 379 cases (50.9% female) that met the full inclusion criteria; of these, 246 were incident cases. Among these, 132 patients resided in the NMH neighborhood, 89 of which were incident cases. Estimated yearly incidences were stable over the study period, ranging from 0.77 to 1.35/100,000 citywide (average 1.07/100,000) and from 1.41 to 4.60/100,000 in the NMH neighborhood (average 2.92/100,000). The corresponding prevalence values increased progressively, from 4.68 to 14.42/100,000 citywide and from 15.64 to 32.58/100,000 in the NMH neighborhood.

Conclusion

The incidence and prevalence of achalasia in central Chicago diagnosed using state-of-the-art technology and diagnostic criteria are at least 2–3-fold greater than previous estimates. Additional studies are needed to determine the generalizability of these data to other regions.

Keywords: achalasia, epidemiology, incidence, prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological studies of achalasia are essential in providing insight into this rare disease, but performing accurate epidemiological studies of achalasia is challenging. Globally reported incidence values range widely from 0.03 – 1.63/100,000 persons per year 1–7 and prevalence from 1.8 – 12.6/100,000 persons per year 2, 3, 7, 8 suggesting wide disparities in either the incidence of the disease or in its detection. Most existing estimates were based on achalasia diagnoses utilizing conventional manometry or, in older studies, barium esophagram. 1 The limited available data from the United States were based on small reviews of hospital discharge data 4 or physician surveys. 5 More recently, high-resolution manometry (HRM) has been adopted as a technologic advance that likely improves the standardization of motility testing and improves its diagnostic sensitivity for achalasia. 9, 10 In parallel with the adoption of HRM, an objective classification scheme for esophageal motility disorders (the Chicago Classification) was developed utilizing HRM-specific metrics that likely also enhanced the recognition of achalasia. 11

Our medical center has been a leader in the management of esophageal motility disorders for decades, attracting referrals both from within the Chicago metropolitan area and regionally. We were also early adopters of HRM technology, utilizing this for all of our clinical studies since 2005 and leading the global effort in the development and maturation of the Chicago Classification [CC v3.0]. 11 Based on this experience, during which we encountered hundreds of achalasia patients annually, we hypothesized that achalasia was more common than suggested by existing epidemiological studies. However, getting an accurate estimate of achalasia incidence requires not only a population-based dataset, but also uniform access to high quality diagnostics within that population-based dataset, and that combination is very challenging within the US health care matrix. In fact, to our knowledge, no such dataset exists. In our case, some compromise needed to be made in defining a population-based sample to circumvent referral bias. Hence, we decided to analyze the epidemiology of achalasia in Chicago assuming that we encountered every incident case at our institution, thereby allowing us to use the city demographics as a population-based denominator. We hypothesized that, although this assumption is not true, it will only result in an under-estimation of achalasia incidence and prevalence and that the magnitude of that under-estimation will increase with increasing geographic separation from our institution. Hence, the aim of this study was to estimate the incidence and prevalence of achalasia between 2004 and 2014: 1) in the entire adult population of Chicago, and 2) in the neighborhoods surrounding Northwestern Memorial Hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cases and study design

We conducted a retrospective longitudinal study of achalasia cases using the Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse (NMEDW), a comprehensive and integrated database of Northwestern Medicine electronic health records (EHRs). We collected patient demographics and address histories for all patients ages ≥18 years with an encounter diagnosis of achalasia and/or idiopathic esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction (EGJOO) between 2004 and 2014. Case definition/inclusion criteria included an encounter diagnosis based on the final impression of the treating physician of idiopathic achalasia and/or idiopathic EGJOO and not diagnosed as such in the prior two years and residence within the city of Chicago. As EGJOO is heterogeneous, we included only idiopathic cases that were managed as achalasia and assumed to be instances of early or incompletely expressed achalasia. 11 Dates of diagnosis were determined and diagnoses were confirmed by manual review of diagnostic test reports (i.e., esophageal manometry and barium esophagram) and physicians’ notes performed by one investigator (SS). Subjects were excluded for incorrect coding of achalasia, absence of EHRs available for review, or secondary achalasia such as that attributable to prior fundoplication or mechanical obstruction. The Northwestern University Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (#STU00200613).

NMEDW search procedure/zip codes data extraction

The NMEDW was queried for achalasia cases based on the case inclusion criteria mentioned above using the International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 530.0 for achalasia. The EGJOO cases were identified in NMEDW by performing a free text search of the manometry report notes, as there was no ICD-9 code for this entity. This list was crosschecked with recorded patient address histories to determine which patients also lived in Chicago for at least some time during the study period. Cases were included in prevalence rate calculations during all years that the patient had an active Chicago address on file. If individuals were first diagnosed with achalasia during a year they lived in Chicago, they were also included in the incidence calculations.

We hypothesized that our capture rate for incident achalasia cases would be greatest in the neighborhoods closest to Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Therefore, in addition to calculating the rates for the entire city of Chicago we grouped 13 zip codes surrounding Northwestern Memorial Hospital (60601, 60602, 60603, 60604, 60605, 60606, 60610, 60611, 60613, 60614, 60654, 60657 and 60661) and analyzed that data separately since their residents would be more likely to visit Northwestern than another institution (this will be referred to as NMH Neighborhood throughout this paper). Figure 1 illustrates a map of the city of Chicago highlighting the NMH Neighborhood area and the major academic and community medical centers in the city. Data for the entire city also included that of the NMH Neighborhood.

Figure 1.

Map of the NMH Neighborhood (thick line) and the city of Chicago (thin line) along with the locations of major academic and community medical centers in the city.

Incidence and Prevalence Calculation

Assuming that the population remained fairly stable during the study period, we used the US 2000 Census Bureau population data as the denominator for incidence and prevalence rates for the years 2004 and 2005 and 2010 population data as the denominator for the years from 2006 – 2014. The total adult population for the city of Chicago was 2,136,154 in 2000 and 2,073,968 in 2010. For the NMH Neighborhood, the total adult population was 255,769 in 2000 and 282,331 in 2010. Incidence rates were calculated by dividing the number of new resident cases within each year by the total population, and prevalence rates were calculated by dividing the number of total resident cases within each year by the total population. Cases with unknown dates of diagnosis were mostly diagnosed before 2000 and were included in prevalence, but not incidence, calculations. Rates are reported per 100,000 persons per year.

Statistics

Total annual as well as gender-based incidence and prevalence rates were calculated along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI), as estimated using the Clopper-Pearson interval method. R version 3.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was used for the statistical analysis.

RESULTS

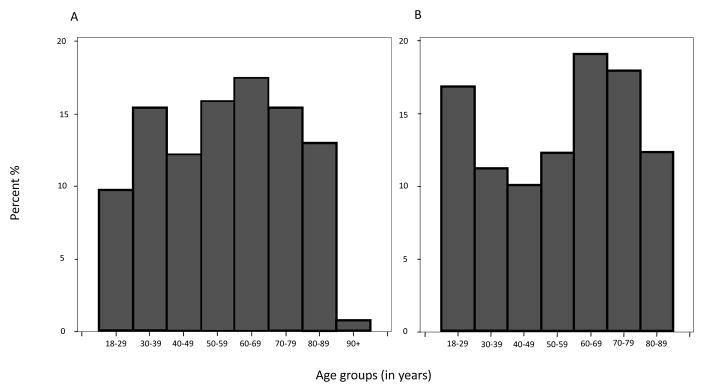

The initial NMEDW query identified 545 potential cases (achalasia and EGJOO combined) that had addresses within Chicago during the study period; additional review excluded 166 cases for various reasons as follows, mostly for incorrect coding: gastroesophageal reflux disease [49], secondary achalasia (previous surgery and/or mechanical obstruction) [20], oropharyngeal dysphagia [13], eosinophilic esophagitis [12], aperistalsis in scleroderma [8], aperistalsis [4], jackhammer esophagus [3], hypertensive peristalsis-nutcracker esophagus [1], esophageal varices [1], esophageal diverticulum [1], rumination syndrome [1], functional dyspepsia [2], peptic ulcer disease [1], gastric outlet obstruction [1], gastroparesis [4], eosinophilic gastroenteritis [1], fake test patient [2], nausea secondary to constipation [1], no objective esophageal disorder identified [34], incomplete work-up [1], no EHRs available to review [5], and diagnosed outside the study period [1]. A total of 379 cases (50.9% female) met full inclusion criteria (11 cases had unknown dates of diagnosis), of which 246 (mean age at diagnosis 56 years, range 20 – 95, 50.4% female) were incident cases. Among the total and incident cases in the city, 23 and 21 patients with EGJOO were included, respectively. Within the NMH Neighborhood, 132 cases (41.7% female) met full inclusion criteria (4 cases had unknown dates of diagnosis), of which 89 (mean age at diagnosis 56 years, range 22 – 89, 38.2% females) were incident cases. Among the total and incident cases in the NMH Neighborhood, 8 and 7 patients with EGJOO were included, respectively. Figure 2 illustrates the age distribution of incident cases in Chicago (Panel A) and the NMH Neighborhood (Panel B) during the entire study period.

Figures 2.

Histogram of age distribution of incident cases in Chicago (Panel A) and the NMH Neighborhood (Panel B) during the entire study period.

Incidence

The incidence of achalasia for Chicago ranged from 0.77 – 1.35/100,000 persons per year and for the NMH Neighborhood from 1.41 – 4.60/100,000 persons per year. The mean incidence over the 11-year period for Chicago was 1.07/100,000 and for the NMH Neighborhood was 2.92/100,000. When we calculated incidence by gender for Chicago, the rates for females ranged from 0.65 – 1.50/100,000 (mean 1.05/100,000) and for males from 0.60 – 1.59/100,000 (mean 1.10/100,000). For the NMH Neighborhood, the rates for females ranged from 0.68 – 4.10/100,000 (mean 2.15/100,000) and for males from 0.73 – 7.34/100,000 (mean 3.73/100,000). The overall incidence varied from year to year but remained relatively stable over the study period. Figure 3 represents the yearly total and gender-based incidence with the 95% CIs for Chicago and the NMH Neighborhood (Panel A: Total, Panel B: Females, Panel C: Males). Male incidence was noticeably greater in the NMH Neighborhood beginning in 2010.

Figure 3.

Incidence rates for Chicago and the NMH neighborhood with 95% CIs (Panel A: Total, Panel B: Females, Panel C: Males).

CI: confidence interval.

Prevalence

Achalasia prevalence for Chicago ranged from 4.68 – 14.42/100,000 persons per year and for the NMH Neighborhood from 15.64 – 32.58/100,000 persons per year. When we calculated prevalence by gender for Chicago, the rates for females ranged from 4.56 – 13.95/100,000 and for males from 4.81 – 14.91/100,000. For the NMH Neighborhood, the rates for females ranged from 11.50 – 28.05/100,000 and for males from 19.94 – 37.45/100,000. The overall prevalence increased throughout the study period. Figure 4 represents the yearly total and gender-based prevalence with the 95% CIs for Chicago and the NMH Neighborhood (Panel A: Total, Panel B: Females, Panel C: Males). Male prevalence was noticeably higher throughout the study period.

Figure 4.

Prevalence rates for Chicago and the NMH Neighborhood with 95% CIs (Panel A: Total, Panel B: Females, Panel C: Males).

CI: confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to reconcile the seemingly low epidemiological estimates of achalasia incidence and prevalence with our recent clinical experience at a major academic referral center for motility disorders in central Chicago suggesting it to be more common. We analyzed data from 2004–2014, a time span during which we utilized HRM and a very consistent state-of-the-art diagnostic approach to achalasia. We approximated a population-based sample by utilizing US census data of Chicago demographics and assuming that we encountered every incident achalasia case in the city. Recognizing that the validity of that assumption was greatest in our immediate neighborhood and less so in the city at large, we calculated our estimates of incidence and prevalence both for the NMH Neighborhood comprised of approximately 275,000 adults and for the city as a whole, comprised of about 2.1 million adults. Consistent with our hypothesis, our major finding was that the incidence of achalasia in the NMH Neighborhood was relatively stable ranging from 1.41 – 4.60/100,000 persons per year over this 11-year span, averaging 2.92/100,000 persons per year. These estimates are about twice the upper limit of previous estimates. Even for the city at large our estimates of achalasia incidence ranged from 0.77 – 1.35/100,000 persons per year averaging 1.07/100,000 persons per year, which is consistent with previous estimates. As for prevalence data, we found this to be consistently greater than previous estimates and to progressively increase throughout the study period, peaking at 32.58/100,000 persons per year in the NMH Neighborhood, almost three times the upper limit of previous estimates. Table 1 summarizes previous studies of achalasia epidemiology globally.

Table 1.

Incidence and prevalence of achalasia globally, in descending order from recent to oldest. Rates are per 100,000 persons/year.

| City/Region | Time period | Incidence rate | Prevalence rate | Case inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Korea 16 | 2007–2011 | 0.39 | 6.29 | ICD-10 code K22.0 |

| Veneto, Italy 6 | 2001–2005 | 1.59 | Not reported | ICD-9-CM code 530.0 of hospital discharge data |

| Alberta, Canada 7 | 1995–2008 | 1.63 | 10.82 | ICD-9-CM code 530.0 and CCP procedure codes 54.92A (endoscopic balloon dilatation) and 54.6 (surgical esophagomyotomy) |

| Leicester, UK 17 | 1986–2005 | 0.89 | Not reported | Hospital discharge data; South Asian population only |

| Iceland 3 | 1952–2002 | 0.55 | 8.7 | ICD codes 530.0 and K22.0. Records were reviewed to excluded miscoded cases |

| Singapore 2 | 1989–1996 | 0.3 | 1.8 | Prospective study, identified new patients referred to motility laboratory of a single hospital |

| Edinburgh, UK 18 | 1986–1991 | 0.8 | Not reported | Prospective study, identified new patients referred for esophageal manometry at a single hospital |

| Zimbabwe 1 | 1974–1983 | 0.03 | Not reported | Review of hospital case notes and operation reports of all black patients with achalasia at 3 hospitals |

| Oxford, UK 19 | 1974–1983 | 0.9 male/0.9 female | 9.99 | Computer-based records of hospital discharges |

| Scotland 19 | 1974–1983 | 1.1 male/1.2 female | 11.2 | Computer-based records of hospital discharges |

| Nottingham, UK 20 | 1966–1983 | 0.5 | 8.0 | Computer-based classification of hospital discharges |

| Virginia, USA 5 | 1975–1978 | 0.6 | Not reported | Questionnaire surveying physicians in Virginia |

| Israel 8 | 1973–1978 | 0.8 | 7.9–12.6 | Screening all regional hospitals and departments of gastroenterology for a diagnosis of achalasia |

| Cardiff, UK 21 | 1926–1977 | 0.4 | Not reported | Records review of all resident patients in Cardiff |

| Rochester, USA 4 | 1935–1964 | 0.6 | Not reported | Records review of all resident patients in Rochester |

ICD: International Classification of Diseases, CCP: Canadian Classification of Procedures.

Although substantially greater than previously reported, our achalasia incidence estimate for the NMH Neighborhood was still likely an under-estimate because it assumed: 1) that every incident achalasia case in the NMH Neighborhood was diagnosed, and 2) that every incident case was managed at NMH. Clearly, neither of these assumptions was true. Achalasia is not a fatal disease and we simply do not know what fraction of cases goes undetected. A very large population-based HRM study would be required to really answer this question. As for the second assumption, although we do command a large market share, the reality of competing insurance networks, the uninsured, and the under-insured make it a virtual certainty that a substantial number of cases are managed elsewhere. However, both of these sources of error result in under-estimating the incidence of achalasia. When the city at large is considered, the magnitude of both of these sources of error increases substantially, but even then the incidence value that we report (1.07/100,000) is in line with the upper limits as detailed in Table 1.

Previous reports (Table 1) have estimated the upper limits of achalasia prevalence as approximately 15 times greater than the incidence. Hence, it is difficult to reconcile the progressive increase in prevalence evident in Figure 4, even as the value now triples that of previous estimates. One could argue that the rising prevalence over time is likely due to the chronic, low-mortality nature of achalasia 12 leading us to simply accumulate cases over time. However, it still should plateau at some point, albeit at a value substantially greater than the incidence value. Given that the mean age of diagnosis in the NMH Neighborhood was 56 years of age and assuming an average life expectancy at age of 56 in the United States is 26.2 years 13, one would anticipate that achalasia prevalence would stabilize at a value about 26 times the incidence or, in this case, at 76/100,000 population, approaching 0.1%. Evidently, even after 11 years, we can anticipate that the trend of increasing prevalence will continue for many years to come. Other possible explanations for rising prevalence are that patients tend to reside in or move to areas close to esophageal centers of excellence such as ours or, more likely, that the increased awareness of the disease and advancement in diagnostics has resulted in increased recognition of the disease.

Previous epidemiological studies of achalasia were based on diagnoses made with conventional manometry. The current study is the first report of achalasia epidemiology in the United States conducted uniformly utilizing HRM in the diagnostic evaluation. HRM, which has been utilized at NMH since 2004 and has been uniformly utilized since 2005, offers improved characterization of esophageal contractility, particularly lower esophageal sphincter (LES) relaxation, an essential diagnostic criterion for achalasia. The integrated relaxation pressure metric, a cornerstone of Chicago Classification criteria, offers improved sensitivity and specificity to diagnose achalasia over conventional manometry. 10 This may well have contributed to our central finding that achalasia is more common than previously thought. Ultimately, it appears that HRM may detect more patients with achalasia than conventional manometry, a premise also supported by a recent randomized European study. 14

As with any retrospective or population-based epidemiological study of rare diseases, our study is subject to and limited by potential biases such as referral bias and difference in access to healthcare resources. Furthermore, our prevalence data may be an overestimate because of referral bias to our center and we may have under-estimated emigration from the population if patients did not update address information in our EHRs. Other potential limitations are accuracy of diagnostic and address information recorded (a general problem with administrative databases). 15 Coding errors may have caused our search strategy to fail to identify and include some patients. However, one strength of our study is that we rigorously reviewed all patient charts to only include patients that had an achalasia diagnosis confirmed. Furthermore, we took the conservative approach of excluding patients with insufficient records for review, even though they may actually have had achalasia.

In conclusion, our study indicates that the incidence of achalasia in central Chicago is at least twice the upper limit of previous estimates from around the world and the prevalence is at least three times greater. We speculate that the higher rates are due to recent advancements in diagnostics (HRM), in diagnostic criteria (the Chicago Classification), and enhanced awareness of the disease. Additional studies are needed to determine the generalizability of these data to other regions.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: grant R01 DK 079902 from the Public Health Service.

An abstract reporting some data of this study was presented as a poster during the Digestive Disease Week meeting in May 2016 in San Diego, CA.

Abbreviation used in this paper

- CC

the Chicago Classification

- CI

confidence interval

- EGJOO

esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction

- EHR

electronic health record

- HRM

high-resolution manometry

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases-Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification

- LES

lower esophageal sphincter

- NMEDW

Northwestern Medicine Enterprise Data Warehouse

- NMH

Northwestern Memorial Hospital

Footnotes

Conflict of interest/financial disclosure: Salih Samo, Dustin A. Carlson, Dyanna L. Gregory, Susan H. Gawel, and Peter J. Kahrilas have nothing to disclose. John E. Pandolfino: Medtronic (Consultant, Grant, Speaking), Sandhill Scientific (Consulting, Speaking), Takeda (Speaking), Astra Zeneca (Speaking).

Author contributions: Salih Samo designed the study, collected and analyzed data, designed graphs, performed literature review, wrote the first draft and approved the final version of the manuscript. Dyanna L. Gregory contributed to study design, collected data, designed graphs, reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. Susan H. Gawel contributed to study design, performed the statistical analysis, designed graphs, reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. Dustin A. Carlson and John E. Pandolfino contributed to study design, reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version. Peter J. Kahrilas designed the study, designed graphs, reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

References

- 1.Stein CM, Gelfand M, Taylor HG. Achalasia in Zimbabwean blacks. S Afr Med J. 1985;67:261–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho KY, Tay HH, Kang JY. A prospective study of the clinical features, manometric findings, incidence and prevalence of achalasia in Singapore. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:791–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birgisson S, Richter JE. Achalasia in Iceland, 1952–2002: an epidemiologic study. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1855–60. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earlam RJ, Ellis FH, Jr, Nobrega FT. Achalasia of the esophagus in a small urban community. Mayo Clin Proc. 1969;44:478–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galen EA, Switz DM, Zfass AM. Achalasia: incidence and treatment in Virginia. Va Med. 1982;109:183–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gennaro N, Portale G, Gallo C, et al. Esophageal achalasia in the Veneto region: epidemiology and treatment. Epidemiology and treatment of achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:423–8. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadowski DC, Ackah F, Jiang B, et al. Achalasia: incidence, prevalence and survival. A population-based study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:e256–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arber N, Grossman A, Lurie B, et al. Epidemiology of achalasia in central Israel. Rarity of esophageal cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1920–5. doi: 10.1007/BF01296119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clouse RE, Staiano A, Alrakawi A, et al. Application of topographical methods to clinical esophageal manometry. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2720–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghosh SK, Pandolfino JE, Rice J, et al. Impaired deglutitive EGJ relaxation in clinical esophageal manometry: a quantitative analysis of 400 patients and 75 controls. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G878–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00252.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3. 0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160–74. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eckardt VF, Hoischen T, Bernhard G. Life expectancy, complications, and causes of death in patients with achalasia: results of a 33-year follow-up investigation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:956–60. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282fbf5e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Actuarial Life Table. Social Security Administration; 2011. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4c6.html. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roman S, Huot L, Zerbib F, et al. High-Resolution Manometry Improves the Diagnosis of Esophageal Motility Disorders in Patients With Dysphagia: A Randomized Multicenter Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:372–80. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Studney DR, Hakstian AR. A comparison of medical record with billing diagnostic information associated with ambulatory medical care. Am J Public Health. 1981;71:145–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim E, Lee H, Jung HK, et al. Achalasia in Korea: an epidemiologic study using a national healthcare database. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:576–80. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.4.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farrukh A, DeCaestecker J, Mayberry JF. An epidemiological study of achalasia among the South Asian population of Leicester, 1986–2005. Dysphagia. 2008;23:161–4. doi: 10.1007/s00455-007-9116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard PJ, Maher L, Pryde A, et al. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edinburgh. Gut. 1992;33:1011–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Variations in the prevalence of achalasia in Great Britain and Ireland: an epidemiological study based on hospital admissions. Q J Med. 1987;62:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Studies of incidence and prevalence of achalasia in the Nottingham area. Q J Med. 1985;56:451–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayberry JF, Rhodes J. Achalasia in the city of Cardiff from 1926 to 1977. Digestion. 1980;20:248–52. doi: 10.1159/000198446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]