Abstract

Objectives

We sought to examine near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) imaging findings of aortocoronary saphenous vein grafts (SVGs).

Background

SVGs are prone to develop atherosclerosis similar to native coronary arteries. They have received little study using NIRS.

Methods

We examined the clinical characteristics and imaging findings from 43 patients who underwent NIRS imaging of 45 SVGs at our institution between 2009 and 2016.

Results

The mean patient age was 67 ± 7 years and 98% were men, with high prevalence of diabetes mellitus (56%), hypertension (95%), and dyslipidemia (95%). Mean SVG age was 7 ± 7 years, mean SVG lipid core burden index (LCBI) was 53 ± 60 and mean maxLCBI4mm was 194 ± 234. Twelve SVGs (27%) had lipid core plaques (2 yellow blocks on the block chemogram), with a higher prevalence in SVGs older than 5 years (46% vs. 5%, p=0.002). Older SVG age was associated with higher LCBI (r=0.480, p<0.001) and higher maxLCBI4mm (r=0.567, p<0.001). On univariate analysis, greater annual total cholesterol exposure was associated with higher SVG LCBI (r=0.30, p=0.042) and annual LDL-cholesterol and triglyceride exposure were associated with higher SVG maxLCBI4mm (LDL-C: r=0.41, p=0.020; triglycerides: r=0.36, p=0.043). On multivariate analysis, the only independent predictor of SVG LCBI and maxLCBI4mm was SVG age. SVG percutaneous coronary intervention was performed in 63% of the patients. An embolic protection device was used in 96% of SVG PCIs. Periprocedural myocardial infarction occurred in one patient.

Conclusions

Older SVG age and greater lipid exposure are associated with higher SVG lipid burden.

Introduction

Saphenous veins grafts (SVGs) are commonly used during coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG), in spite of high rates of early and late failure (1–6). Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) is an imaging modality that can detect lipid core plaque (LCP) in the vessel wall with high sensitivity and specificity. NIRS has been used to characterize native coronary arteries, demonstrating its ability to identify culprit plaques responsible for acute coronary syndromes (ACS) (7–10). NIRS-detected LCP in non-culprit vessels has been associated with higher risk for major adverse cardiac events (MACE) at one year (11), suggesting that NIRS may be able to assist with risk stratification. SVG lesions often have complex characteristics as assessed by angiography (2,12,13), intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) (13–17), and optical coherence tomography (OCT) (18,19), but only one study has examined SVGs using intravascular NIRS (20). We examined SVG NIRS imaging findings and their association with patient clinical characteristics, including lipid exposure since bypass grafting (21).

Methods

Patient population

We examined the clinical characteristics and imaging findings from 43 patients who underwent NIRS imaging of 45 SVGs at our institution between 2009 and 2016 as part of the Lipid cORe Plaque Association With CLinical Events Near-InfraRed Spectroscopy (ORACLE-NIRS) Registry (Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT02265146). Data were collected and entered retrospectively and prospectively into a dedicated database. Patients who underwent clinically indicated cardiac catheterization and NIRS or NIRS-IVUS imaging were enrolled in the registry. The cohort included patients with various indications for imaging, including angiographic follow-up one year after bypass graft surgery as part of a research protocol (n=11) (CABG-PRO: Cardiac Catheterization for Bypass Graft Patency Rate Optimization trial, NCT01063491)(22) and angiographic follow-up one year after SVG stenting as part of another research protocol (n=2) (SOS-Xience V: Study of the Xience V Everolimus-eluting Stent in Saphenous Vein Graft Lesions, NCT00911976)(23). The indications for diagnostic coronary angiography and NIRS imaging are summarized in Figure 1. NIRS was performed in order to further clarify angiographic findings and to assist in risk stratification. SVG PCI was performed as clinically indicated.

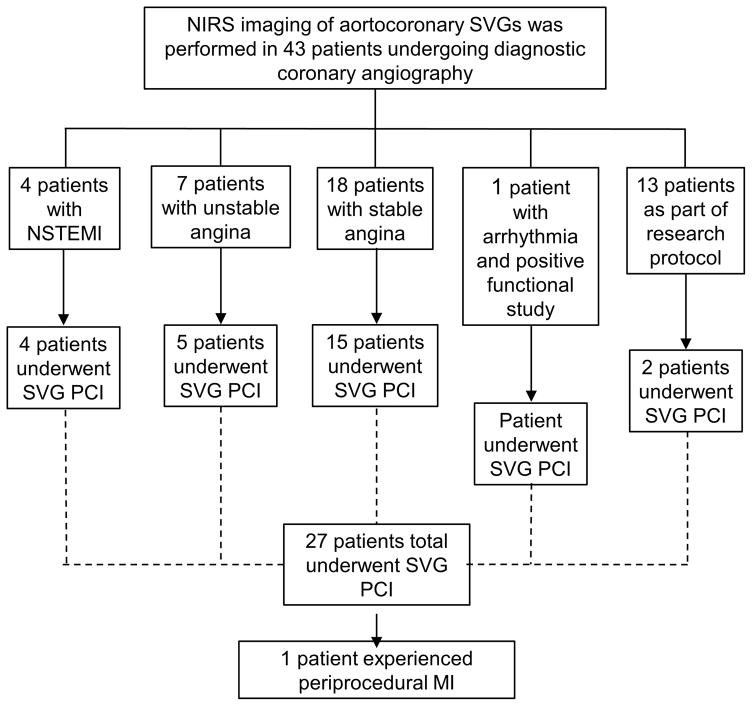

Figure 1.

Indications and outcomes of diagnostic coronary angiography and NIRS imaging in the study population. Of 43 patients who underwent coronary angiography and NIRS imaging, saphenous vein graft percutaneous coronary intervention was indicated in 27 patients.

Femoral access was used in all cases and intravenous heparin or bivalirudin was administered for anticoagulation during the catheterization procedure, at the discretion of the operator. NIRS-IVUS imaging was performed after intragraft administration of nitroglycerin (100–200mcg). Periprocedural myocardial infarction was defined as creatine-kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) elevated to more than three times the upper limit of normal (ULN; 6.3 ng/dL at our institution). The study was approved by the institutional review board.

Lipid Exposure

Lipid exposure was calculated using the method described by Zhu et al. (21). All available lipid assays from the date of the most recent CABG surgery until 3 months after the date of NIRS imaging were obtained. Measurements for total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) were plotted against time, and the area under the curve was calculated for each patient and each graft. Values for total lipid exposure for each patient were divided by the number of years between the first and last lipid measurement to obtain an annual lipid exposure for total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-C, and LDL-C. A daily lipid exposure was calculated by dividing the annual lipid exposures by 365 days. Annual lipid exposures were correlated with NIRS imaging findings.

Near-infrared spectroscopy analysis

NIRS images were acquired with a 3.2 French catheter that simultaneously co-registers IVUS data (InfraRedx, Burlington, MA). A built-in automated pullback and rotation device allowed a uniform speed of 0.5 millimeters per second and 960 rotations per minute. Data were transferred to DVDs for storage and offline analysis using EchoPlaque 4 Analysis Software (INDEC Medical Systems, Santa Clara, CA). All NIRS measurements were performed prior to PCI.

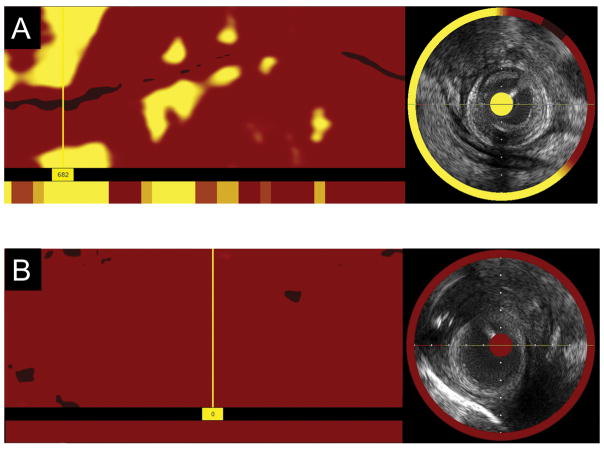

Raw NIRS data were processed by a NIRS algorithm developed using histology as the gold standard for lipid detection (24). Prospective studies have validated this algorithm for LCP detection with a receiver-operating characteristic area-under-the-curve of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.76–0.85). The algorithm constructs a virtual color image called a chemogram for each pullback, which maps the probability of the presence of lipid in the vessel wall, with yellow color representing higher probability of lipid and red representing low probability of lipid (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Examples of saphenous vein grafts from the study population.

A) Longitudinal chemogram and ring chemogram in a 10 year old saphenous vein graft. The maxLCBI4mm is 682 and is indicated by the location of the marker.

B) Longitudinal chemogram and ring chemogram in a one year old saphenous vein graft. The maxLCBI4mm is 0.

LCBI, lipid core burden index.

The lipid core burden index (LCBI) is a measure of the lipid burden for a given length of vessel, calculated by dividing the number of yellow pixels by the total number of pixels available, multiplied by 1000 (LCBI range: 0–1000). The maxLCBI4mm is a measure that identifies the highest LCBI of a 4mm segment within the vessel of interest. For the purpose of this study, a LCP of interest was defined as a region with a maxLCBI4mm >500.

IVUS analysis

Offline IVUS analysis was performed for all pre-intervention IVUS pullbacks available for the study SVGs using EchoPlaque, version 4.0 (INDEC Medical Systems, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Luminal and external media borders were contoured for frames at free stepping intervals approximately 5mm apart. Quantitative IVUS measurements performed were the following: vessel volume, plaque volume, and lumen volume; plaque burden (plaque volume divided by vessel volume); and minimum luminal area and diameter. A plaque on IVUS was defined as an area of plaque burden of at least 40% on at least three consecutive IVUS frames (25).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation, and discrete variables were reported as percentages. Continuous normally distributed variables were compared using Student’s t-test and continuous non-parametric variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Discrete variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Correlations between two continuous variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. All statistical analysis was performed using JMP Software, Version 12.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A two-sided p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

The mean patient age was 67 ± 7 years and 98% were men, with high prevalence of diabetes mellitus (56%), hypertension (95%), and dyslipidemia (95%). The clinical characteristics of the patient population are summarized in Table 1. Mean SVG age was 7 ± 7 years.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study patients.

| Demographics | n=43 |

|---|---|

| Age* | 67 ± 7 |

| Gender (%) | 98 |

| Diabetes (%) | 56 |

| Hypertension (%) | 95 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 95 |

| Tobacco use (%) | 23 |

| Statin use (%) | 95 |

|

| |

| Periprocedural serum lipids | |

|

| |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL)* | 148 ± 52 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL)* | 77 ± 37 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)* | 36 ± 13 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL)* | 185 ± 143 |

|

| |

| Annual lipid exposures | |

|

| |

| Annual total cholesterol exposure (mg/dL)* | 60178 ± 12743 |

| Annual triglyceride exposure (mg/dL)* | 68385 ± 32443 |

| Annual HDL cholesterol exposure (mg/dL)* | 14413 ± 3445 |

| Annual LDL cholesterol exposure (mg/dL)* | 33468 ± 13552 |

|

| |

| Daily lipid exposures | |

|

| |

| Daily total cholesterol exposure (mg/dL)* | 165 ± 35 |

| Daily triglyceride exposure (mg/dL)* | 187 ± 89 |

| Daily HDL cholesterol exposure (mg/dL)* | 39 ± 9 |

| Daily LDL cholesterol exposure (mg/dL)* | 92 ± 37 |

Mean ± standard deviation

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Angiographic characteristics

The angiographic and IVUS characteristics of the SVGs in the study population are summarized in Table 2. There was a total of 95 SVGs in the cohort, with a mean of 2.2 SVGs per patient. Sixty-three of the SVGs were diseased (defined as stenosis ≥30% on angiography), with a mean of 1.5 diseased SVGs per patient. Nine SVGs were occluded (defined as 100% stenosis), with a mean of 0.2 occluded SVGs per patient. Diseased SVGs were significantly more likely to have LCPs than non-diseased SVGs (33% vs. 0%, p=0.044).

Table 2.

Angiographic and IVUS characteristics of SVGs in the study population

| Overall number of SVGs | SVGs ≥5 years | SVGs <5 years | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angiographic characteristics | N=95 | n=51 | n=44 | |

|

| ||||

| Mean number of SVGs per patient* | 2.2±0.6 | 2.2±0.7 | 2.2±0.5 | 0.93 |

| Number of diseased SVGs | 63 | 42 | 21 | 0.006 |

| Mean number of diseased SVGs per patient* | 1.5±0.9 | 1.8±0.8 | 1.1±0.9 | |

| Number of occluded SVGs | 9 | 1 | 8 | |

| Mean number of occluded SVGs per patient* | 0.2±0.6 | 0.3±0.7 | 0.1±0.2 | 0.069 |

| Mean SVG % stenosis in vessel studied by NIRS* | 60±34 | 76±18 | 42±38 | <0.001 |

| Mean SVG % stenosis in PCI target vessel* | 81±13 | |||

|

| ||||

| IVUS characteristics | N=21 | n=6 | n=15 | |

|

| ||||

| Number of SVG plaques | 54 | |||

| Mean number of SVG plaques per patient* | 2.8±2.4 | 4.2±3.9 | 2.4±1.6 | 0.36 |

| Mean number of plaques per SVG* | 2.6±1.7 | 3.5±2.0 | 2.2±1.5 | 0.19 |

| Number of LCPs in SVGs | 7 | 7 | 0 | |

| Mean number of LCPs per SVG* | 0.3±0.8 | 1.2±1.2 | 0 | 0.058 |

| Mean minimum luminal area in SVG (mm2)* | 5.8±2.6 | 5.5±2.1 | 5.9±2.8 | 0.70 |

| Mean minimum luminal diameter in SVG (mm)* | 2.4±0.6 | 2.3±0.3 | 2.5±0.6 | 0.40 |

| Mean SVG vessel volume (mm3)* | 1018±341 | 1010±115 | 1020±402 | 0.93 |

| Mean SVG lumen volume (mm3)* | 632±241 | 579±87 | 653±280 | 0.37 |

| Mean SVG plaque volume (mm3)* | 386±140 | 431±87 | 368±155 | 0.25 |

| Mean SVG plaque burden (%)* | 39 | 43 | 37 | 0.13 |

mean±standard deviation

NIRS Imaging

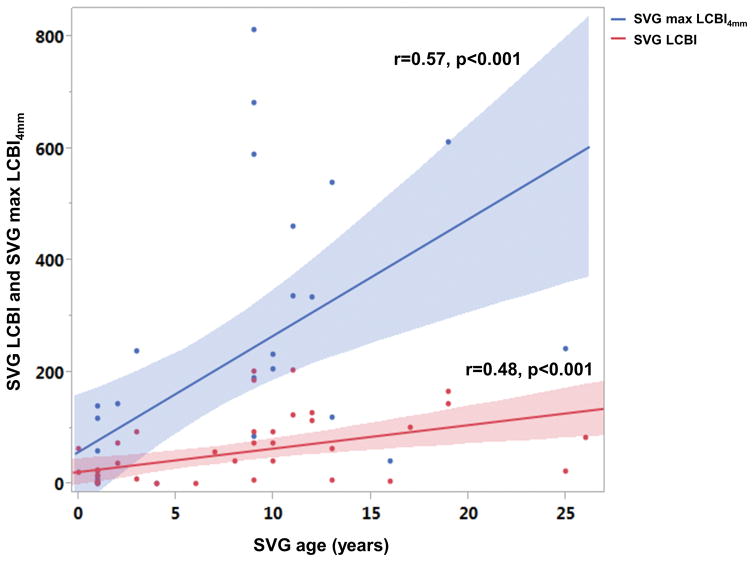

NIRS imaging was performed in 45 SVGs. In cases where more than one SVG was available for imaging, the selection of SVG(s) for NIRS was at the discretion of the operator. NIRS was performed using a single-modality catheter in 24 SVGs; a dual-modality NIRS-IVUS catheter was used to perform NIRS in the remaining 21 SVGs. Mean SVG LCBI was 53 ± 60 and mean maxLCBI4mm was 194 ± 234. Twelve of the SVGs (27%) had LCPs (2 yellow blocks on the block chemogram) and 5 of them (11%) had large SVG lipid core plaques (maxLCBI4mm>500). There was higher prevalence of LCPs (2 yellow blocks on block chemogram) in SVGs older than 5 years (5% vs. 46%, p=0.002) (Figure 2). On univariate analysis, older SVG age was associated with higher LCBI (r=0.480, p<0.001) (Figure 3) and higher maxLCBI4mm (r=0.567, p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Relationship between SVG age and SVG LCBI and SVG max LCBI4mm.

SVG, saphenous vein graft; LCBI, lipid core burden index.

IVUS Characteristics

The IVUS characteristics of the SVGs in the study population are summarized in Table 2. There were a total of 54 plaques in 21 SVGs, with a mean of 2.6 plaques per SVG and 2.8 plaques per patient. Seven (13%) of these 54 plaques were lipid core plaques. The mean minimum luminal area was 5.8mm2; the mean minimum luminal diameter was 2.4 mm. The mean plaque burden was 39%. SVGs ≥5 years and older were associated with numerically greater plaque burden (43% vs. 37%, p=0.13), numerically smaller minimum lumen area (5.5 vs. 5.9 mm2, p=0.70), and numerically smaller minimum luminal diameter (2.3 vs. 2.5 mm, p=0.40).

Of the seven LCPs with available IVUS data, positive remodeling was observed in two cases, while the remaining five SVGs exhibited negative remodeling at the plaque site. Five of the plaques were eccentric.

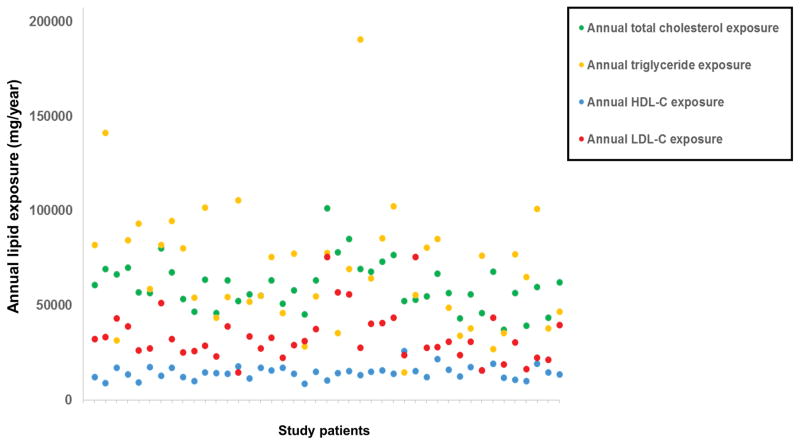

Lipid exposure

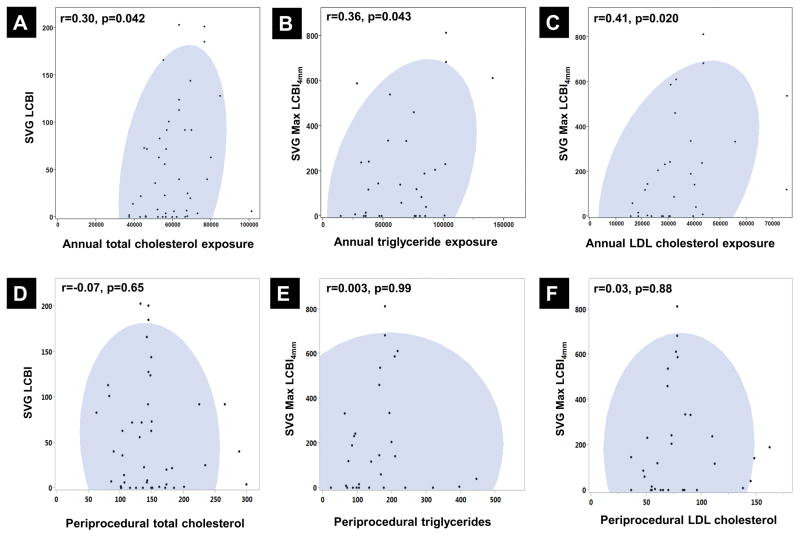

The mean periprocedural lipid measurements and annual lipid exposures for the study population are shown in Table 1 and Figure 4. Greater annual lipid exposure was associated with NIRS measures of lipid burden, while single periprocedural lipid measurements showed no association with NIRS measures (Figure 5). Annual total cholesterol exposure was associated with high SVG LCBI (r=0.30, p=0.042). Annual LDL cholesterol exposure and triglyceride exposure were associated with higher SVG maxLCBI4mm (LDL-C: r= 0.41, p= 0.020; triglycerides: r=0.36, p=0.043).

Figure 4.

Annualized lipid exposures in the study population.

HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Figure 5.

A) Relationship between annual total cholesterol exposure and SVG LCBI

B) Relationship between annual triglyceride exposure and SVG max LCBI4mm

C) Relationship between annual LDL-cholesterol exposure and SVG max LCBI4mm

D) Relationship between periprocedural total cholesterol and SVG LCBI

E) Relationship between periprocedural triglycerides and SVG max LCBI4mm

F) Relationship between periprocedural LDL cholesterol and SVG max LCBI4mm

SVG, saphenous vein graft; LCBI, lipid core burden index; LDL, low-density lipoprotein

Multivariate analysis showed that SVG age was the only independent predictor of LCBI (beta coefficient 3.7, p=0.005) and higher maxLCBI4mm (beta coefficient 14.8, p=0.030).

SVG Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Twenty-seven out of 43 (63%) patients underwent SVG PCI (Figure 1). The mean SVG % stenosis among patients who underwent SVG PCI was 81% vs. 20% (p<0.001) in those who did not undergo SVG PCI. There was a total of 28 PCI target SVGs; of these, an LCP was present at the target site in 10 (36%). The proportion of PCI target vessels with LCPs did not differ significantly among patients with various indications for catheterization. Thrombus was observed at the PCI target in two cases. An embolic protection device was used in 27 SVG PCIs (96%). Only one of 27 patients experienced periprocedural myocardial infarction. Histologic analysis of debris captured by the embolic protection devices was not performed, but slow flow was noted in one of the study patients during SVG PCI.

Discussion

The main finding of our study is that LCPs are relatively commonly found in SVGs and that older SVG age and lipid exposure is associated with higher incidence of LCP.

The progression of atherosclerosis in saphenous vein grafts has been well described (26–28). In a large study with angiographic follow-up at 4–5 years, SVG age was an important predictor of progression of atherosclerosis (29). In accord with these findings, our intravascular imaging study showed that time since bypass grafting is independently associated with atherosclerosis measured as lipid burden using NIRS imaging, likely due to prolonged exposure to atherosclerosis risk factors, such as hyperlipidemia and hypertension, similar to native coronary arteries.

Consistent with the NIRS findings, angiographic stenosis was significantly greater among SVGs aged 5 years and older (76% vs. 42%, p<0.001). As expected, the IVUS data available for our cohort indicates that older SVGs tended to have greater plaque burden and smaller luminal minimum luminal area and diameter, findings associated with negative remodeling.

The SVGs analyzed in our study had a relatively low prevalence of LCPs (13% of IVUS-defined plaques were LCPs), all of which occurred in the SVGs aged 5 years or older. Despite the relatively low proportion of LCPs, the mean plaque burden was relatively high (39%), indicating that the vein graft disease observed in this cohort could be due to intima/media hyperplasia and fibrosis.

There was no association between a single periprocedural lipid assay and SVG LCBI or maxLCBI4mm, but annualized lipid exposures showed a significant relationship with NIRS imaging parameters on univariate analysis. Our findings show that greater SVG LCBI is seen in patients with greater annual total cholesterol exposure since bypass grafting, and greater maxLCBI4mm is seen in patients with greater annual LDL-C and triglyceride exposure. The association between higher triglyceride exposure and LCP is consistent with the previously described relationship between hypertriglyceridemia and late myocardial infarction following bypass grafting (30). Zhu and colleagues calculated annualized lipid exposure for 436 SVGs and showed that graft failure was associated with increased total cholesterol/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C exposure (21). Although our study did not assess long-term outcomes, NIRS lipid burden in non-culprit vessels has been shown to be associated with cardiovascular events during follow-up (11).

The only other study of SVGs using NIRS has shown a moderate relationship between lesion LCBI and preprocedural HDL-cholesterol measurements (r=−0.43, p=0.04), but no relationship with other lipid measurements (3). This difference in observed relationships is likely due to the temporal variability in lipid levels; annualized lipid exposure represents a more robust measure than a single lipid measurement.

Interventions directed at specifically preventing SVG atherosclerosis are important, given that post-CABG patients frequently continue to suffer from the same coronary artery disease risk factors that had contributed to development of advanced coronary disease requiring surgical revascularization (31). Our study shows that even relatively well-controlled lipid levels may provide a significant exposure over time, with the development of LCPs in SVGs occurring after 5 years in about half of SVGs. The beneficial impact of lipid-lowering therapy in prolonging SVG patency has been demonstrated (32–34).

Consistent with current guidelines (35) the use of embolic protection for SVG stenting was high in the study population, explaining the low incidence of periprocedural myocardial infarction.

Limitations

Our study is limited by the retrospective design and relatively small study population; however, it is the largest NIRS study performed in SVGs. The study may have been underpowered to detect an association between NIRS parameters and serum lipid levels. Larger NIRS studies of SVG patients will clarify these relationships. Additionally, NIRS could have limited ability to detect lipid in the relatively large SVG lumen. Although lipid detection using NIRS has been validated in native coronary arteries, such studies have not been performed in non-native vessels.

For practical reasons and to minimize risk, in most cases only one SVG was imaged using NIRS, which may have resulted in selection bias. In addition, selection bias may have been introduced by inclusion of asymptomatic patients undergoing angiography as part of participation in a research study, as described in the Methods section. NIRS-IVUS data was available for only a portion of the study cohort.

The method used to calculate lipid exposure depended on retrospective chart review of all available lipid assays. The frequency of lipid measurements varied greatly between patients, and may have impacted the precision of the calculation. Patients with higher lipid levels may have had more frequent measurements due to monitoring of therapy, and thus had more accurate lipid exposure calculations than patients with physiological lipid levels. In addition, the method used to calculate the lipid exposure required estimation of the area under the curve of the lipid measurements using a numerical integration method, which may have introduced a small degree of error. Lastly, the mostly male study population may limit the generalizability of our findings to women.

Conclusions

Greater SVG lipid burden is seen in older SVGs and in patients with greater lipid exposure. SVG age is an independent predictor of NIRS lipid burden.

Acknowledgments

The ORACLE-NIRS registry was supported by a research grant from InfraRedx, Inc.

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.1 REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for importing data from external sources.

The study was also supported by CTSA NIH Grant UL 1-RR024982.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Dr. Muller: consultant, InfraRedx.

Dr. Banerjee: research grants from Gilead and the Medicines Company; consultant/speaker honoraria from Covidien and Medtronic; ownership in MDCARE Global (spouse); intellectual property in HygeiaTel.

Dr. Brilakis: consulting/speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular, Asahi, Boston Scientific, Elsevier, Somahlution, St Jude Medical, and Terumo; research support from Boston Scientific and InfraRedx; spouse is employee of Medtronic.

Remaining authors: none

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009; 42(2):377–81.

References

- 1.Safian RD. Accelerated atherosclerosis in saphenous vein bypass grafts: a spectrum of diffuse plaque instability. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2002;44:437–48. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2002.123471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitzgibbon GM, Kafka HP, Leach AJ, Keon WJ, Hooper GD, Burton JR. Coronary bypass graft fate and patient outcome: angiographic follow-up of 5,065 grafts related to survival and reoperation in 1,388 patients during 25 years. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:616–26. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00206-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campeau L, Enjalbert M, Lesperance J, Bourassa MG, Kwiterovich P, Jr, Wacholder S, Sniderman A. The relation of risk factors to the development of atherosclerosis in saphenous-vein bypass grafts and the progression of disease in the native circulation. A study 10 years after aortocoronary bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:1329–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198411223112101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourassa MG, Enjalbert M, Campeau L, Lesperance J. Progression of atherosclerosis in coronary arteries and bypass grafts: ten years later. Am J Cardiol. 1984;53:102C–107C. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90759-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hess CN, Lopes RD, Gibson CM, Hager R, Wojdyla DM, Englum BR, Mack MJ, Califf RM, Kouchoukos NT, Peterson ED, et al. Saphenous vein graft failure after coronary artery bypass surgery: insights from PREVENT IV. Circulation. 2014;130:1445–51. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.008193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grondin CM, Campeau L, Lesperance J, Enjalbert M, Bourassa MG. Comparison of late changes in internal mammary artery and saphenous vein grafts in two consecutive series of patients 10 years after operation. Circulation. 1984;70:I208–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madder RD, Goldstein JA, Madden SP, Puri R, Wolski K, Hendricks M, Sum ST, Kini A, Sharma S, Rizik D, et al. Detection by near-infrared spectroscopy of large lipid core plaques at culprit sites in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:838–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madder RD, Husaini M, Davis AT, Van Oosterhout S, Harnek J, Gotberg M, Erlinge D. Detection by near-infrared spectroscopy of large lipid cores at culprit sites in patients with non-st-segment elevation myocardial infarction and unstable angina. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ccd.25754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madder RD, Smith JL, Dixon SR, Goldstein JA. Composition of target lesions by near-infrared spectroscopy in patients with acute coronary syndrome versus stable angina. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:55–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.963934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madder RD, Wohns DH, Muller JE. Detection by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy of lipid core plaque at culprit sites in survivors of cardiac arrest. J Invasive Cardiol. 2014;26:78–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oemrawsingh RM, Cheng JM, Garcia-Garcia HM, van Geuns RJ, de Boer SP, Simsek C, Kardys I, Lenzen MJ, van Domburg RT, Regar E, et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy predicts cardiovascular outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2510–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman S, Zadina K, Moritz T, Ovitt T, Sethi G, Copeland JG, Thottapurathu L, Krasnicka B, Ellis N, Anderson RJ, et al. Long-term patency of saphenous vein and left internal mammary artery grafts after coronary artery bypass surgery: results from a Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canos DA, Mintz GS, Berzingi CO, Apple S, Kotani J, Pichard AD, Satler LF, Suddath WO, Waksman R, Lindsay J, Jr, et al. Clinical, angiographic, and intravascular ultrasound characteristics of early saphenous vein graft failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:53–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jim MH, Hau WK, Ko RL, Siu CW, Ho HH, Yiu KH, Lau CP, Chow WH. Virtual histology by intravascular ultrasound study on degenerative aortocoronary saphenous vein grafts. Heart Vessels. 2010;25:175–81. doi: 10.1007/s00380-009-1185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi T, Makuuchi H, Naruse Y, Sato T, Fujiki T, Ninomiya M, Ogata K, Komiyama N. Assessment of saphenous vein graft wall characteristics with intravascular ultrasound imaging. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;46:701–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03217805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murphy GJ, Angelini GD. Insights into the pathogenesis of vein graft disease: lessons from intravascular ultrasound. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2004;2:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaneda H, Terashima M, Takahashi T, Iversen S, Felderhoff T, Grube E, Yock PG, Honda Y, Fitzgerald PJ. Mechanisms of lumen narrowing of saphenous vein bypass grafts 12 months after implantation: an intravascular ultrasound study. Am Heart J. 2006;151:726–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adlam D, Antoniades C, Lee R, Diesch J, Shirodaria C, Taggart D, Leeson P, Channon KM. OCT characteristics of saphenous vein graft atherosclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:807–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ybarra LF, Weisz G, Rached FH, Perin MA, Caixeta A. Early saphenous vein graft in-stent neoatherosclerosis by optical coherence tomography. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30:1462e15–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood FO, Badhey N, Garcia B, Abdel-karim AR, Maini B, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Analysis of saphenous vein graft lesion composition using near-infrared spectroscopy and intravascular ultrasonography with virtual histology. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:528–33. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu YY, Hayward PA, Hare DL, Reid C, Stewart AG, Buxton BF. Effect of lipid exposure on graft patency and clinical outcomes: arteries and veins are different. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45:323–8. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezt261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotsia AP, Papafaklis MI, Michael TT, Rangan BV, Peltz M, Roesle M, Jessen M, Willis B, Christopoulos G, Nakas G, et al. Serial Multimodality Evaluation of Aortocoronary Bypass Grafts During the First Year After CABG Surgery. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1341–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brilakis ES, Lichtenwalter C, Abdel-karim AR, de Lemos JA, Obel O, Addo T, Roesle M, Haagen D, Rangan BV, Saeed B, et al. Continued benefit from paclitaxel-eluting compared with bare-metal stent implantation in saphenous vein graft lesions during long-term follow-up of the SOS (Stenting of Saphenous Vein Grafts) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:176–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gardner CM, Tan H, Hull EL, Lisauskas JB, Sum ST, Meese TM, Jiang C, Madden SP, Caplan JD, Burke AP, et al. Detection of lipid core coronary plaques in autopsy specimens with a novel catheter-based near-infrared spectroscopy system. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:638–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, de Bruyne B, Cristea E, Mintz GS, Mehran R, McPherson J, Farhat N, Marso SP, et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parang P, Arora R. Coronary vein graft disease: pathogenesis and prevention. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:e57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70486-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harskamp RE, Lopes RD, Baisden CE, de Winter RJ, Alexander JH. Saphenous vein graft failure after coronary artery bypass surgery: pathophysiology, management, and future directions. Ann Surg. 2013;257:824–33. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288c38d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalan JM, Roberts WC. Morphologic findings in saphenous veins used as coronary arterial bypass conduits for longer than 1 year: necropsy analysis of 53 patients, 123 saphenous veins, and 1865 five-millimeter segments of veins. Am Heart J. 1990;119:1164–84. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(05)80249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Domanski MJ, Borkowf CB, Campeau L, Knatterud GL, White C, Hoogwerf B, Rosenberg Y, Geller NL. Prognostic factors for atherosclerosis progression in saphenous vein grafts: the postcoronary artery bypass graft (Post-CABG) trial. Post-CABG Trial Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:1877–83. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00973-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Brussel BL, Plokker HW, Ernst SM, Ernst NM, Knaepen PJ, Koomen EM, Tijssen JG, Vermeulen FE, Voors AA. Venous coronary artery bypass surgery. A 15-year follow-up study. Circulation. 1993;88:II87–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boatman DM, Saeed B, Varghese I, Peters CT, Daye J, Haider A, Roesle M, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery patients undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography have multiple uncontrolled coronary artery disease risk factors and high risk for cardiovascular events. Heart Vessels. 2009;24:241–6. doi: 10.1007/s00380-008-1114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Post Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Trial I. The effect of aggressive lowering of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and low-dose anticoagulation on obstructive changes in saphenous-vein coronary-artery bypass grafts. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:153–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701163360301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Azen SP, Mack WJ, Cashin-Hemphill L, LaBree L, Shircore AM, Selzer RH, Blankenhorn DH, Hodis HN. Progression of coronary artery disease predicts clinical coronary events. Long-term follow-up from the Cholesterol Lowering Atherosclerosis Study. Circulation. 1996;93:34–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kulik A, Voisine P, Mathieu P, Masters RG, Mesana TG, Le May MR, Ruel M. Statin therapy and saphenous vein graft disease after coronary bypass surgery: analysis from the CASCADE randomized trial. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:1284–90. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.04.107. discussion 1290–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Cercek B, Chambers CE, Ellis SG, Guyton RA, Hollenberg SM, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–651. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]