Abstract

Background:

Cervical spine fractures occur in 2.6% to 4.7% of trauma patients aged 65 years or older. Mortality rates in this population ranges from 19% to 24%. A few studies have specifically looked at dysphagia in elderly patients with cervical spine injury.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to evaluate dysphagia, disposition, and mortality in elderly patients with cervical spine injury.

Settings and Design:

Retrospective review at an the American College of Surgeons-verified level 1 trauma center.

Methods:

Patients 65 years or older with cervical spine fracture, either isolated or in association with other minor injuries were included in the study. Data included demographics, injury details, neurologic deficits, dysphagia evaluation and treatment, hospitalization details, and outcomes.

Statistical Analysis:

Categorical and continuous data were analyzed using Chi-square analysis and one-way analysis of variance, respectively.

Results:

Of 136 patients in this study, 2 (1.5%) had a sensory deficit alone, 4 (2.9%) had a motor deficit alone, and 4 (2.9%) had a combined sensory and motor deficit. Nearly one-third of patients (n = 43, 31.6%) underwent formal swallow evaluation, and 4 (2.9%) had a nasogastric tube or Dobhoff tube placed for enteral nutrition, whereas eight others (5.9%) had a gastrostomy tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placed. Most patients were discharged to a skilled nursing unit (n = 50, 36.8%), or to home or home with home health (n = 48, 35.3%). Seven patients (5.1%) died in the hospital, and eight more (5.9%) were transferred to hospice.

Conclusion:

Cervical spine injury in the elderly patient can lead to significant consequences, including dysphagia and need for skilled nursing care at discharge.

Key Words: Cervical spine fracture, dysphagia, elderly, enteral feeding, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic injuries are a frequent source of morbidity and mortality worldwide. It has been estimated that trauma results in 37 million emergency room visits and 2.6 million hospital admissions annually.[1] Trauma has been found to be the 7th leading cause of death in those 65 years of age or older.[2] It has also been estimated that by 2050 this age group will represent 25% of the USA population.[2] The prevalence of cervical spine fractures in those aged 65 years or older ranges from 2.6% to 4.7%.[3] As life expectancy continues to increase and the Baby Boomer generation ages, there will be a larger number of people 65 years of age or older and a correspondingly higher proportion of elderly individuals that will be involved in accidents resulting in cervical spine injuries. These injuries can be potentially devastating to the elderly patient, and preexisting comorbidities can have a significant impact on outcomes. Previous studies have shown mortality rates of 21%–30% in those ≥65 years of age, but have not focused primarily on isolated cervical spine fractures.[3,4]

One potential complication associated with cervical spine injury is dysphagia. Dysphagia in the elderly patient may necessitate short-term placement of a Dobhoff feeding tube or potentially a more long-term placement of a gastrostomy tube. Patient's disposition status could have an effect on the choice of enteral access. A few studies have specifically looked at dysphagia in the elderly patient with a cervical spine injury.

Commonly, patients that survive cervical spine fractures are unable to be discharged home and are discharged to a rehabilitation facility or skilled nursing facility.[3,4] This could potentially be a permanent change for a person that was previously living independently. Data regarding disposition and potential enteral feeding options will provide clinicians with an improved ability to counsel not only patients but their families in regards to prognosis and long-term outcomes. The purpose of this study was to evaluate dysphagia, disposition, and mortality in elderly patients with cervical spine injury.

METHODS

A retrospective review was conducted of all patients 65 years of age or older that were admitted with a cervical spine fracture, either isolated or in association with other relatively minor injuries, to an American College of Surgeons-verified level 1 trauma center between January 01, 2001 and December 31, 2011. Eligible patients also had data available regarding the presence of dysphagia. As a screening tool, the trauma center's registry was queried to identify trauma patients 65 years of age or older with a cervical spine fracture and an Injury Severity Score (ISS) <15. Patient data were then retrieved from the trauma registry as well as from patients' medical records, which were reviewed to verify that a cervical spine fracture was present, and as either an isolated injury or with only other minor injuries. Patients with minor injuries that would not be expected to impact hospital course or outcomes were included in the study. Minor injuries were defined as abrasions, lacerations, contusions, extremity fractures, and American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Grade 1 or 2 intraabdominal injuries.

Once a cervical spine injury was confirmed, variables collected from the medical record included: demographics (age, gender, race), patient transport information, ISS and Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS), Glasgow coma scale score, ultrasound (Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma) findings, comorbidities on admission, medications on admission, arrived intubated or intubated on arrival, neurologic events, individual injuries and need for operative or procedural management, sensory and motor deficits, complications, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission and length of stay, ventilator requirements, invasive adjuncts (tracheostomy, gastrostomy tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube), swallow evaluation, need for nasogastric tube or Dobhoff feeding tube for enteral nutrition, delayed diagnosis, do not resuscitate or code status, comfort care, hospital length of stay, discharge destination (i.e., home, rehabilitation, skilled nursing facility, etc…), mortality, and unanticipated readmission or reintubation.

All patients admitted with cervical injury were given a clinical bedside swallow evaluation by the intensive care nurse. A bedside evaluation was conducted once the patient was alert, appropriate to commands and could sit upright. The evaluation first involved giving the patient one ice chip. If the patient exhibited no difficulty swallowing and no cough, they were then given a teaspoon of water to swallow. Again, if there was no cough or difficulty swallowing, the patient was given 30 ml of water. If the patient had no difficulty swallowing this and was without cough, they were given 90 ml of water to swallow. If the patient was able to ingest the 90 ml of water without a cough or difficulty swallowing, they were cleared for oral intake. The patients that were able to tolerate all three phases of the bedside evaluation were considered to be without dysphagia and comprised our “no dysphagia” study group. If the patient showed any evidence of difficulty swallowing or a cough during the bedside evaluation at any stage, a speech therapist was consulted to administer a formal swallow evaluation. In all cases in which a speech therapy consultation was ordered, the patient was found to have dysphagia, and those patients comprised our “dysphagia” study group.

The Institutional Review Board of Via Christi Hospitals Wichita, Inc., approved this study for implementation.

Continuous data are reported as the mean ± the standard deviation of the mean and frequencies are reported for categorical data. Primary comparisons were made between the patients with or without dysphagia. Continuous variables were compared using one-way analysis of variance. Categorical data were compared using Chi-square analysis or the Fisher's exact test when appropriate. All tests were two-tailed, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Somers, New York, USA).

RESULTS

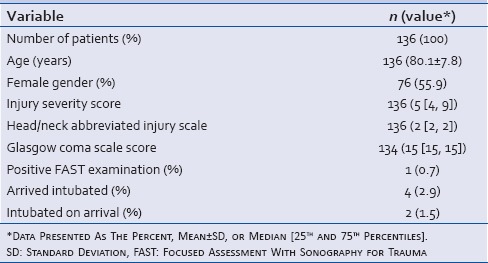

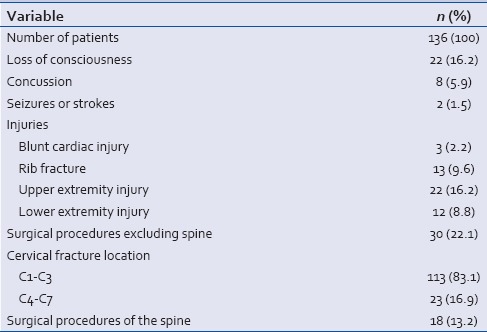

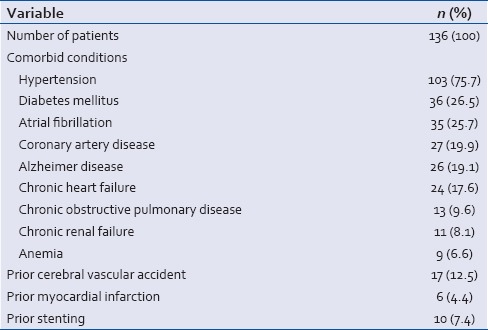

A total of 136 patients met the study inclusion criteria. A summary of our study population is provided in Tables 1–3. Patients were predominately female (55.9%) and Caucasian (n = 126, 92.6%), with an average age of 80.1 years [Table 1]. The median ISS was 5 and head/neck AIS was 2. The majority of patients were transported to our trauma center from another facility or hospital (n = 91, 66.9%). The most common comorbidities identified were hypertension (75.7%), diabetes mellitus (26.5%), and atrial fibrillation [25.7%; Table 2]. The majority of patients were on an anti-hypertensive (n = 95, 69.9%) and/or an anticoagulant, which included aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin (n = 75, 55.1%). Other common medications at the time of injury included diuretics (n = 52, 38.2%), lipid-lowering agents (n = 41, 30.1%), and B-blockers (n = 39, 28.7%). Approximately 16% of patients suffered a loss of consciousness and concussions were sustained in 5.9% of patients [Table 3]. There was no associated lung, intraabdominal, or pelvic injuries identified. The most common injuries observed in addition to the patient's cervical spine injury were upper extremity injuries (16.2%), rib fractures (9.6%), and lower extremity injuries (8.8%). With these additional injuries, 22.1% of patients (n = 30) had surgical procedures, excluding spine surgery, performed. Eighteen patients (13.2%) required a surgical procedure of the spine.

Table 1.

Study patient demographics, injury severity, and trauma procedures

Table 3.

Procedures performed and injury characteristics

Table 2.

Patient comorbidities at the time of admission

All 136 patients who met study inclusion criteria were confirmed with computed tomography imaging of the cervical spine to have a fracture. Two patients (1.5%) had a sensory deficit alone, 4 (2.9%) had a motor deficit alone, and 4 (2.9%) had a combined sensory and motor deficit. Only one of these patients (0.7%) required insertion of a short-term feeding tube for enteral nutrition. This was a patient with a motor deficit related to a prior stroke. The majority of patients arrived to the hospital with a Miami J Collar for neck stabilization during transport (n = 130, 95.6%).

Of the 136 patients in the study, 93 (68.4%) passed their clinical bedside swallow evaluation, and these patients represented our “no dysphagia” group. Nearly one-third of patients (n = 43, 31.6%) failed a clinical bedside swallow evaluation and required a formal swallow evaluation performed by a speech therapist. All of these patients (n = 43) showed signs of dysphagia and comprised our “dysphagia” study group. Short-term feeding tubes (nasogastric tubes or Dobhoff feeding tubes) were placed in a total of 4 dysphagia patients (2.9%), while long-term feeding tubes (gastrostomy tubes) were placed in a total of 8 dysphagia patients (5.9%), 1 of which had a short-term feeding tube placed initially. Eight of the dysphagia patients (5.9%) underwent surgical repair of their spinal injury, and another 5 (3.7%) underwent Halo fixation for their injury. Ten no dysphagia patients (7.4%) required surgical repair of their spinal injury while 3 (2.2%) underwent halo fixation of their injury.

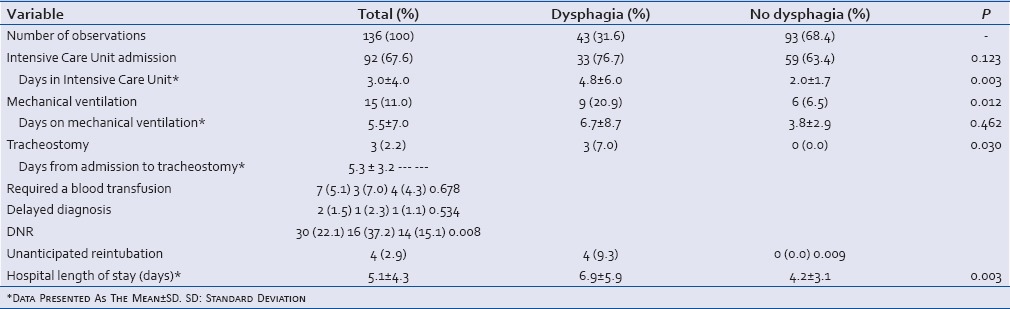

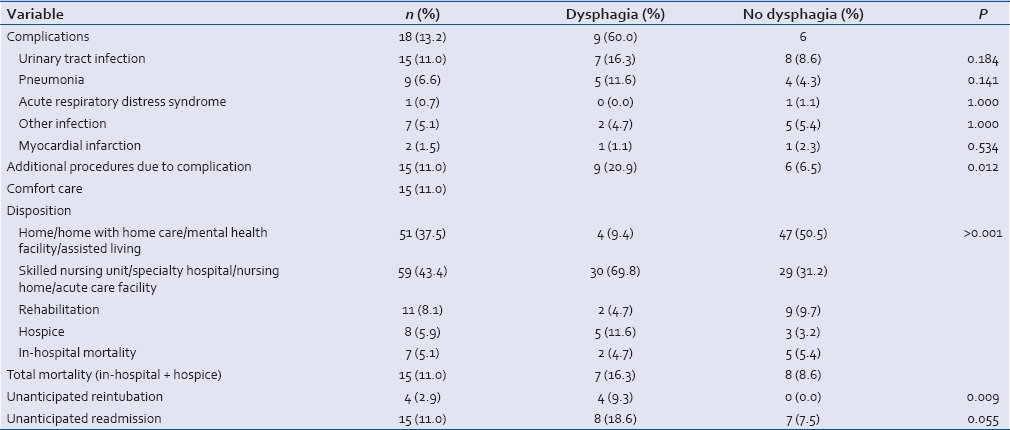

The majority of patients were admitted to an ICU (67.6%), and the mean and median length of stay in the ICU were 3.0 and 2 days, respectively [Table 4]. Mechanical ventilation was required in 11.0% of patients and the mean and median number of days on the ventilator was 5.3 and 3 days, respectively. The mean length of hospital stay was 5.1 days. The most common complication identified in the patient population was a urinary tract infection (11.0%). Other observed complications are detailed in Table 5. Infections, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and line infections did not occur. Thrombotic complications such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus were also not observed in this population.

Table 4.

Hospitalization details

Table 5.

Complications and disposition

The largest proportion of patients were discharged to a skilled nursing unit (n = 50, 36.8%). The next largest group was discharged to home or to home with home care [n = 48, 35.3%; Table 5]. Nine point six percent of patients were discharged to a rehabilitation facility or assisted living. In-hospital mortality was found to be 5.1% among the population. An additional 5.9% were discharged to hospice and presumed to have died. Taking into consideration in-hospital mortality and hospice discharge, the overall expected mortality was 11.0%.

A comparison was made between patients with dysphagia (n = 43) and those without dysphagia [n = 93, Tables 4 and 5]. Patients with dysphagia were older than those without dysphagia (82.8 ± 6.9 vs. 78.8 ± 7.9 years, respectively; P = 0.006), and interestingly, more often suffered from Alzheimer's disease (n = 17, 39.5% vs. n = 9, 9.7%, P < 0.001). While not significant, there was a trend for more patients with dysphagia to have arrived at the hospital intubated than those without dysphagia (n = 3, 7.0% vs. n = 1, 1.1%, P = 0.093). Those with dysphagia also required more additional procedures due to complications [20.9% vs. 6.5%, P = 0.012; Table 5], although complication rates were not different between the groups. While those with dysphagia were not admitted to the ICU more often (76.7% vs. 63.4%) they did have longer ICU stays than those without dysphagia (4.8 vs. 2.0 days, P = 0.003). As expected, those with dysphagia were placed on mechanical ventilation more often (20.9% vs. 6.5%, P = 0.012), but they were not ventilated longer than those without dysphagia when mechanical ventilation was required (6.7 vs. 3.8 days). The only patients requiring tracheostomy (7.0% vs. 0.0%, P = 0.030) or a surgical gastrostomy (n = 8, 18.6% vs. n = 0, 0.0%, P < 0.001) were those with dysphagia. Those with dysphagia were also hospitalized longer than those without dysphagia (6.9 vs. 4.2 days, P = 0.003). In-hospital mortality was not greater in those with dysphagia (4.7% vs. 5.4%), but those with dysphagia were more often discharged to a skilled nursing unit (62.8, vs. 24.7%) or to hospice (11.6 vs. 3.2%) as compared to those without dysphagia who were more often discharged to home or home with home health (47.3 vs. 9.4%, P < 0.001). Unanticipated readmissions (18.6%, vs. 7.5%, P = 0.055) and unanticipated reintubations (n = 4, 9.3% vs. 0, 0.0%, P = 0.009) were more common in those with dysphagia.

DISCUSSION

A cervical spine fracture in an elderly patient (≥65 years of age) can result in significant morbidity and mortality. Previous studies have estimated the mortality rate in this population to range from 21% to 30%.[5,6,7] In 2008, Golob et al.[3] reported a mortality rate of 25%, which is in line with the published literature, but higher than the 5.1% in-hospital mortality rate found in our study. However, their study included patients with associated traumatic injuries, which may have contributed to the higher mortality rate. In comparison to our findings, the majority of their patients were male (56.0%) and more severely injured with a mean ISS of 17. Ninety-one percent of their patients were admitted to the ICU and 58% required ventilator assistance as compared to 67.6% and 11.0% for patients in our study, respectively. Similar to our findings, this study reported favorable outcomes in 44% of patients (discharge to home or rehabilitation facility) and unfavorable outcomes in 56% (death, discharge to skilled nursing facility or long-term acute care facility). Damadi et al.[4] also reported a higher mortality rate of 24% resulting from higher ISSs, with a mean ISS of 16. This study did not report whether patients had any additional traumatic injuries, although it is likely that it did considering their mean ISS. When looking at isolated cervical spine fractures, the estimated mortality rate may actually be lower than what had previously been reported in the literature as other studies have reported higher mortality rates, but also have higher ISS. Injuries other than those of the cervical spine are likely the cause of the increased ISS and mortality rates cited in prior reports.

There have been limited studies that have examined dysphagia following a cervical spine fracture. In 2008, Malik et al. reported one patient to have transient swallowing difficulty after anterior cervical spine stabilization.[8] An additional study by Garfin et al.[9] in 1986 reported three patients with dysphagia following the use of a Halo fixation device. Eight of our patients were treated with a Halo device. In our study, 31.6% of patients (n = 43) underwent formal swallow evaluation with a speech therapist with confirmed dysphagia. Five of these patients were treated by Halo fixation and an additional eight required other operative repair. We had anticipated that in our population of patients, whose primary injury was a cervical spine fracture, there would be a higher incidence of dysphagia. Of the patients in this study, a total of eight patients (5.9%) had a short-term feeding tube (nasogastric tube or Dobhoff feeding tube) placed, whereas only eight more (5.9%) had a surgical feeding tube placed. These findings raise the question as to whether a mandatory formal swallow evaluation is necessary for all patients following a cervical spine injury. It seems reasonable for a bedside clinical evaluation to be performed by nursing staff and if the patient fails the bedside evaluation, then a more formal swallow evaluation with a speech therapist should be performed.

Another important consideration with cervical spine fracture patients is discharge destination. It is possible that patients who had previously been living independently may be unable to return home. Few studies have specifically looked at discharge destination in patients in whom the primary injury was a cervical spine fracture. Gulati et al.[10] reported 37% of patients were able to be discharged home and 33% of patients were dismissed to a nursing home or community hospital. Golob et al.[3] reported that 17% of patients were able to be discharged home, 27% to a rehabilitation facility, and 30% to a skilled nursing facility or long-term acute care facility. About one-third of the elderly patients in our study were able to return home, but 43.4% of patients were discharged to a skilled nursing facility, nursing home, or long-term acute care facility. These patients may have lived at home before their injury, or they may have been returning to the level of care they received before their injury, but this information was not collected as part of this investigation. Additional long-term studies would be of interest to determine whether patients that had been discharged to skilled nursing care or rehabilitation were able to eventually be discharged to home and returned to their previous level of function.

CONCLUSIONS

Cervical spine injuries, either isolated or associated with other minor injuries, in the elderly patient have the potential to lead to significant long-term consequences. Dysphagia can be a particularly challenging complication following a cervical spine injury in an elderly patient, and in our study was associated with increased length of stay and higher rates of discharge to skilled nursing care. At our institution, we do not routinely require swallow evaluations in our patients with cervical spine injuries. However, in this study, we found that nearly one-third of patients underwent a formal swallow evaluation. This raises the question as to whether elderly patients should routinely undergo a swallow evaluation when a cervical spine injury is identified. Nearly one-third of affected patients required skilled nursing care following their injury, with 17.2% dying or being made comfort care during their hospitalization; findings consistent with previously reported data. Physicians need to be cognizant of the potential for these problems to counsel patients and their families following cervical spine fracture.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Case for Funding Trauma Research. National Trauma Institute. 2012. Oct 2, Available from: http://www.nationaltraumainstitute.org/the_case_for_trauma_funding.html.

- 2.ATLS Student Course Manual 8th Edition. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golob JF, Jr, Claridge JA, Yowler CJ, Como JJ, Peerless JR. Isolated cervical spine fractures in the elderly: A deadly injury. J Trauma. 2008;64:311–5. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181627625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damadi AA, Saxe AW, Fath JJ, Apelgren KN. Cervical spine fractures in patients 65 years or older: A 3-year experience at a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 2008;64:745–8. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3180341fc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spivak JM, Weiss MA, Cotler JM, Call M. Cervical spine injuries in patients 65 and older. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:2302–6. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199410150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin ZN, Arthur M, Mullins RJ, Hart RA. Variations in injury patterns, treatment, and outcome for spinal fracture and paralysis in adult versus geriatric patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:796–802. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000119400.92204.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majercik S, Tashjian RZ, Biffl WL, Harrington DT, Cioffi WG. Halo vest immobilization in the elderly: A death sentence? J Trauma. 2005;59:350–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000174671.07664.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik SA, Murphy M, Connolly P, O'Byrne J. Evaluation of morbidity, mortality and outcome following cervical spine injuries in elderly patients. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:585–91. doi: 10.1007/s00586-008-0603-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garfin SR, Botte MJ, Waters RL, Nickel VL. Complications in the use of the halo fixation device. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:320–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gulati A, Yeo CJ, Cooney AD, McLean AN, Fraser MH, Allan DB. Functional outcome and discharge destination in elderly patients with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:215–8. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]