Abstract

The lectin complement pathway is suggested to play a role in atherogenesis. Pentraxin-3 (PTX3), ficolin-1, ficolin-2, ficolin-3, MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated serine protease-3 (MASP-3) and MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated protein-1 (MAP-1) are molecules related to activation of the lectin complement pathway. We hypothesized that serum levels of these molecules may be associated with the incidence of myocardial infarction (MI). In a Norwegian population-based cohort (HUNT2) where young to middle-aged relatively healthy Caucasians were followed up for a first-time MI from 1995–1997 through 2008, the 370 youngest MI patients were matched by age (range 29–62 years) and gender to 370 controls. After adjustments for traditional risk factors, the two highest tertiles of PTX3 and the highest tertiles of ficolin-2 and MASP-3 were associated with MI, with odds ratios (95% confidence interval) of 1.65 (1.10–2.47) and 2.79 (1.83–4.24) for PTX3, 1.55 (1.04–2.30) for ficolin-2, and 0.63 (0.043–0.94) for MASP-3. Ficolin-1, ficolin-3 and MAP-1 were not associated with MI. In a multimarker analysis of all associated biomarkers, only PTX3 and MASP-3 remained significant. PTX-3 and MASP-3 enhanced prediction of MI compared to the traditional Framingham risk score alone (AUC increased from 0.64 to 0.68, p = 0.006). These results support the role of complement-dependent inflammation in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease.

Atherosclerosis is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the industrialized world1. The typical clinical manifestations of advanced atherosclerosis are myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke, often happening without any prior clinical warning2,3. Prediction models based on clinical parameters, such as the Framingham score for calculating the 10-year risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD)4, are imprecise and 15–20% of patients admitted with MI have no major traditional risk factors5. Thus, early molecular or biochemical warning signals are urgently needed.

Chronic low-grade vascular inflammation plays an essential role in the initiation, progression and destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques6. Among the innate immunity components, activation of the complement system has been associated with both pre-lesional stages and the progression of atherosclerotic lesions7. However, the mechanisms that drive the persistent non-resolving inflammation in the vessel wall remain incompletely understood.

Activation of innate immunity relies on a set of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Recently, long pentraxin-3 (PTX3), a PRR in the same family as C-reactive protein, has emerged as a new candidate risk marker of cardiovascular diseases8. Serum PTX3 levels have been associated with disease severity and mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction9, ischemic stroke10, cancer11, acute respiratory distress syndrome12 and sepsis13. PTX3 is released by multiple cells including monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, and activated endothelial cells upon stimulation by IL-1 and TNF-α, cytokines markedly expressed in atherosclerotic lesions. PTX3 recognizes and binds to foreign molecules, leading to activation of the classical and lectin pathways of the complement cascade14,15.

Several studies have investigated the association between mannose-binding-lectin (MBL), the PRR and initiating factors of the lectin pathway of complement activation, and the risk of MI and cardiovascular disease. Previous results from our group demonstrated that MBL deficiency is associated with an increased risk of severe atherosclerotic disease16,17, suggesting that there exists a genetic predisposition related to the inflammatory system that makes some individuals more susceptible to coronary artery disease. However, the results from various studies have been conflicting and the role of MBL remains debated18.

In addition to MBL, five other PRRs have been reported to be able to activate the lectin pathway by the binding to conserved structures present on various microorganisms or altered host cells: Collectin-10 (collectin liver 1, CL-L1, CL-10), collectin-11 (collectin kidney 1, CL-K1, CL-11), ficolin-1 (M-ficolin), ficolin-2 (L-ficolin) and ficolin-3 (H-ficolin). The PRRs are found in complex with the MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated serine proteases (MASPs), i.e. MASP-1, -2 and -319. In addition, two non-enzymatic proteins associated with the PRRs exists: MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated protein (MAP-1 or Map44) and small MBL-associated protein (sMAP, Map19 or MAP-2). MASP-1 and MASP-2 are crucial for lectin pathway activation, whereas the biological role of MASP-3 remains to be elucidated. Recent evidence indicates that MASP-3 is important for conversion of pro-factor D to active factor D, the initiating enzyme of the alternative pathway of complement, but it may also have a down-regulating effect on the lectin pathway20,21. sMAP plays a regulatory role in the activation of the lectin pathway22, whereas MAP-1 has shown to inhibit the lectin pathway of complement activation23.

The complement system is an intricate system consisting of a complicated network of mediators with many interactive effects. We hypothesized that PRRs and their associated proteins in the lectin pathway regulate the immune response in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the association between serum levels of PTX3, ficolins, MASP-3 and MAP-1 in young and middle aged relatively healthy individuals from the general Norwegian population with the future risk of MI. These might represent novel biomarkers for CVD and potential targets for the development of future treatment strategies.

Results

General characteristics investigation

Baseline characteristics of cases and controls are displayed in Table 1. Conventional cardiovascular risk factors were more frequent among cases: They had higher BMI, a more unfavourable lipid profile, and more often hypertension, diabetes, and family history of myocardial infarction. Cases were more often current smokers and had higher Framingham risk scores. Mean age for MI was 53 years (range 29–62).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Cases | Controls | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 366) | (n = 369) | ||

| Gender, female/male | 87/279 | 88/281 | 0.98 |

| Age, years | 48 (47–48) | 48 (47–48) | 0.94 |

| Age at MI, years | 53 (29–62) | — | — |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.4 (27.0–27.8) | 26.5 (26.1–26.9) | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | 193 (53%) | 162 (44%) | 0.02 |

| - Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 140 (139–142) | 136 (135–138) | < 0.001 |

| - Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 85 (84–87) | 83 (82–84) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 (4%) | 4 (1%) | 0.03 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 90 (89–91) | 90 (89–92) | 0.67 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 242 (66%) | 145 (39%) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 6.8 (6.7–6.9) | 6.0 (5.9–6.2) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 2.53 (2.35–2.70) | 2.05 (1.91–2.19) | <0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/L | 1.18 (1.14–1.23) | 1.28 (1.25–1.32) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | |||

| - Former/never | 133 (37%) | 195 (56%) | <0.001 |

| - Current | 226 (63%) | 155 (44%) | |

| Framingham risk score | 13 (13– 14) | 11 (11–12) | <0.001 |

| Family history of MI* | 100 (27%) | 54 (15%) | <0.001 |

Continuous variables are presented as median (95% CI), categorical variables as n (%). *Myocardial infarction before 60 years in first-degree relatives. HDL, high-density lipoprotein; MI, myocardial infarction.

26 (3.5%) and 10 (1.4%) patients had missing data on smoking and creatinine, respectively. Otherwise, missing values for background characteristics were generally low (<0.2%).

Correlation between serum biomarkers and conventional clinical variables

In linear regression, the R2-values were generally low (<0.1), indicating that the variables included explained a fraction of the plethora of variation in biomarker concentration. PTX3 and MAP-1 were not associated with any risk factors. Ficolin-2 (p < 0.001), ficolin-3 (p = 0.03) and MASP-3 (p = 0.03) were associated with BMI, and ficolin-2 was also associated with smoking (p = 0.01). Ficolin-1 was associated with sex (p = 0.002) and creatinine (p = 0.03).

Association of serum biomarkers with the risk of future myocardial infarction

Serum concentrations of the biomarkers are displayed in Table 2. PTX3 (p < 0.001) and ficolin-2 (p < 0.001) were higher among cases, also after adjustments for classical risk factors. MASP-3 was lower among cases (p = 0.03) and this remained significant after adjustments for conventional CVD risk factors.

Table 2. Serum concentrations of the different biomarkers.

| Median concentration (±95% confidence interval) |

P-value |

Missing, % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Unadjusted* | Adjusted | ||

| Pentraxin-3, ng/ml | 2.96 (2.75–3.17) | 2.16 (1.99–2.35) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 5.7% |

| Ficolin-1, μg/ml | 0.44 (0.41–0.46) | 0.47 (0.44–0.51) | 0.31 | 0.63 | 0 |

| Ficolin-2, μg/ml | 5.07 (4.89–5.26) | 4.57 (4.38–4.75) | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0 |

| Ficolin-3, μg/ml | 25.4 (24.3–26.5) | 24.2 (23.1–25.4) | 0.09 | 0.78 | 0.4% |

| MASP-3, μg/ml | 4.50 (4.16–4.87) | 4.98 (4.65–5.34) | 0.033 | 0.03 | 2.0% |

| MAP-1, μg/ml | 0.17 (0.16–0.18) | 0.18 (0.17–0.19) | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0 |

*Unadjusted analysis: P-values from Mann-Whitney U-test. Adjusted analysis: P-values from linear regression with robust standard errors with adjustments for age, sex, body mass index, creatinine, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and smoking status. MASP-3, MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated serine protease-3: MAP-1, MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated protein-1.

PTX3 was weakly correlated with ficolin-2 (Rho = 0.09, p = 0.02) and MASP-3 (Rho 0.09, p = 0.02). MASP-3 was further correlated with ficolin-1 (Rho −0.1, p = 0.01) and ficolin-3 (Rho −0.17, p < 0.001). MAP-1 was correlated with ficolin-2 (Rho 0.14, p < 0.001).

The two highest tertiles of PTX3 were associated with an increased incidence of MI, also after adjustments for traditional risk factors (Table 3). The two highest tertiles of ficolin-2 were also associated with MI, however after adjustments, only the highest tertile remained significant. The two highest tertiles of MASP-3 were associated with a decreased risk of MI, but in the final model, this association remained only for the highest tertile. When including these three biomarkers in the same analysis, only the two highest tertiles of PTX3 and the highest tertile of MASP-3 remained significant in the analysis adjusted for conventional risk factors (Table 4).

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis.

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Pentraxin-3 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 1.72 (1.18–2.50) | 0.01 | 1.65 (1.10–2.47) | 0.02 |

| Tertile III | 2.87 (1.95–4.23) | <0.001 | 2.79 (1.83–4.24) | <0.001 |

| Ficolin-1 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 1.02 (0.71–1.47) | 0.9 | 1.10 (0.74–1.62) | 0.64 |

| Tertile III | 0.79 (0.55–1.14) | 0.21 | 0.77 (0.52–1.13) | 0.18 |

| Ficolin-2 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 1.64 (1.13–2.36) | 0.01 | 1.36 (0.92–2.01) | 0.13 |

| Tertile III | 2.00 (1.39–2.89) | <0.001 | 1.55 (1.04–2.30) | 0.03 |

| Ficolin-3 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 1.36 (0.95–1.96) | 0.10 | 1.20 (0.81–1.77) | 0.36 |

| Tertile III | 1.33 (0.92–1.91) | 0.13 | 1.17 (0.79–1.73) | 0.44 |

| MASP-3 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 0.65 (0.45–0.93) | 0.02 | 0.68 (0.46–1.01) | 0.06 |

| Tertile III | 0.66 (0.46–0.95) | 0.02 | 0.63 (0.43–0.94) | 0.02 |

| MAP-1 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 1.23 (0.85–1.77) | 0.27 | 1.16 (0.78–1.71) | 0.46 |

| Tertile III | 0.90 (0.63–1.30) | 0.59 | 0.86 (0.59–1.27) | 0.45 |

CI, confidence interval; MASP-3, MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated serine protease-3; MAP-1, MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated protein-1; OR, odds ratio.

*Adjusted for sex, age, hypertension (yes/no), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), smoking (never or previous/current), diabetes (yes/no) and body mass index.

Table 4. Results from logistic regression including the three biomarkers that emerged as significant in primary analysis.

| Unadjusted |

Adjusted* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| PTX3 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 1.65 (1.12–2.44) | 0.011 | 1.61 (1.07–2.44) | 0.023 |

| Tertile III | 2.93 (1.96–4.37) | <0.0005 | 2.90 (1.89–4.47) | <0.0005 |

| Ficolin-2 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 1.51 (1.03–2.24) | 0.037 | 1.24 (0.82–1.88) | 0.31 |

| Tertile III | 1.84 (1.24–2.73) | 0.003 | 1.41 (0.92–2.16) | 0.11 |

| MASP-3 | ||||

| Tertile I | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||

| Tertile II | 0.67 (0.45–1.0) | 0.049 | 0.68 (0.45–1.05) | 0.080 |

| Tertile III | 0.56 (0.38–0.82) | 0.003 | 0.52 (0.34–0.79) | 0.002 |

CI, confidence interval; MASP-3, MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated serine protease-3; MAP-1, MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated protein-1; OR, odds ratio.

*Adjusted for sex, age, hypertension (yes/no), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), smoking (never or previous/current), diabetes (yes/no) and body mass index.

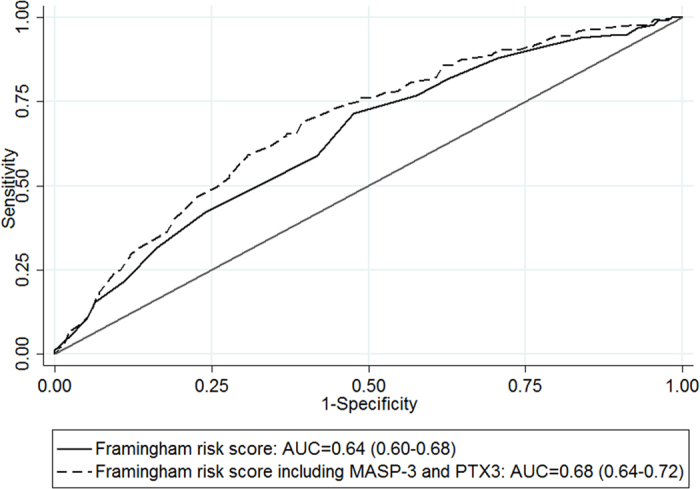

When adding data on PTX3 and MASP-3 to the traditional Framingham score, the area under the receiver-operating characteristics curve (AUC) was significantly increased from 0.64 (0.60–0.68) to 0.68 (0.64–0.72, p = 0.006, Fig. 1). The continuous net reclassification index showed significant improvement (0.35 (0.21–0.49), p < 0.001). The integrated discrimination index was 0.04 (0.03–0.06), p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Comparison of the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (AUC) of the clinical model based on the Framingham risk score, with the model including pentraxin-3 and MBL/ficolin/collectin-associated serine protease-3.

Discussion

The complement system constitutes an important component of innate immunity and atherosclerosis24. In the present study, we found that higher concentrations of PTX3 and ficolin-2, and lower concentrations of MASP-3 were associated with increased risk of MI in middle-aged relatively healthy individuals, independent of conventional CVD risk factors.

The associations of higher PTX3 and ficolin-2 levels with an increased risk of future MI may indicate an influence from a higher activity of the complement system. In line with our findings, higher serum PTX3 levels have been related to CVD risk factors, subclinical atherosclerosis and peripheral vascular diseases, as well as clinical CVD events and incident acute coronary syndromes - independently of CRP and CVD risk factors - in older as well as younger, apparently healthy populations8,25,26. PTX3 is rapidly induced at the tissue level and released into the blood at sites of MI, atherosclerosis, vascular damage or inflammatory lesions27,28,29. Thus, PTX3 is increasingly emerging as a potential biomarker of atherosclerosis and CVD8. Moreover, PTX3 has also been described as a marker of clinically more advanced cardiovascular disease30.

There is increasing evidence that PTX3 possesses atheroprotective properties, suggesting that PTX3 might balance the overactivation of a proinflammatory, proatherogenic cascade27. This was further supported by the demonstration that PTX3 deficiency promotes vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis31. The available evidence therefore suggests that increased levels of PTX3 in patients with CVD reflects a protective physiologic response, which is correlated to disease severity.

A recent study demonstrated that ficolin-2 and MBL are present in human carotid plaques and recognize cholesterol crystals with subsequent activation of the lectin complement pathway32. The present study was not designed to elucidate causal relationships underlying the present associations with MI. However, in previous reports, neither genetic variations influencing blood ficolins nor PTX3 levels influenced the risk of MI17,33. The missing link between the genetic variants determining PTX3 and ficolin-2 levels with the risk of MI suggests that they act as markers of active atherosclerosis and complement activity rather than causal factors.

When performing a multimarker analysis together with PTX3 and MASP-3 as well as adjusting for conventional risk factors, ficolin-2 was no longer significant. The present correlation matrix showed significant, albeit weak correlation between ficolin-2 and PTX3. Previous reports have shown that ficolins interact with PTX3 and MASPs15,34. Nevertheless, the lack of association of ficolin-2 to the risk of MI in the multimarker analysis may suggest that the information added by ficolin-2 was at least partially conveyed by the other markers.

Patients suffering acute MI within the follow-up period presented with lower baseline MASP-3 concentrations. Whereas the enzymatic properties of MASP-1 and MASP-2 in the activation of the lectin complement pathway have been described, the role of MASP-3 remains unclear35. Low levels of MASP-3 may be related to decreased synthesis or increased turnover. Furthermore, we cannot exclude that MASP-3 acts as a marker for other causal relationships. It has been shown that MASPs interact with ficolins, altering the effect of the complement system. An effect of MASP-3 mediated through interactions with other molecules can therefore not be excluded.

In a recent study investigating the associations of components of the lectin pathway and low-grade inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, carotid intima-media thickness and CVD, MASP-3 was associated with endothelial dysfunction, independent of plasma MBL36. The authors suggested a potential role through non-complement pathways. The mechanisms underlying the association between lower MASP-3 concentrations and an increased risk of MI warrants further investigation.

The purpose of this study was not to evaluate the predictive performance of selected biomarkers. Nevertheless, the associations of PTX3, ficolin-2 and MASP-3 may uncover potential new causal mechanisms in the development and progression of coronary heart disease and risk for MI, lead to the generation of new hypotheses and suggest improvements to existing explanatory models. Atherogenesis is characterized by multiple distinct pathways and molecular mechanisms, and our findings underscore the importance of the innate immune response and complement activation. A step further would be to investigate the causal relationships underlying the present associations.

On the other hand, we do not exclude that the described markers may prove useful in a predictive setting. Inclusion of biomarker data significantly improved the AUC, and indicators of predictive ability such as the net reclassification index and integrated discrimination index indicated potential usefulness in clinical prediction. There is a growing interest in developing a multimarker approach for identifying cardiovascular risk37,38,39. The novel markers may be potential targets that can be included in a multimarker panel for predicting CVD and identifying individuals at higher risk of MI, above that of traditional risk factors.

Our study has some limitations: We did not have accurate times to MI to our disposal, and despite exclusion of patients with clinical CVD, the group middle-aged relatively healthy individuals may constitute a heterogeneous study population with subclinical atherosclerosis at different stages.

In conclusion, elevated PTX3, elevated ficolin-2 and low MASP-3 concentrations were associated with increased risk of future MI in young to middle-aged relatively healthy Caucasians. Higher PTX3 and ficolin-2 concentrations may indicate higher complement activity, especially related to the lectin pathway. However, underlying mechanisms and potential use in a predictive setting merits further investigation. Nevertheless, our findings support the involvement of complement-dependent inflammation in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease.

Materials and Methods

The present case-control study was generated from population data in the second wave of the Nord-Trøndelag Health (HUNT2) study, which was matched to data on incident acute MIs. The HUNT2 study was carried out in 1995–97 in the county of Nord-Trøndelag, Norway. This county is fairly representative for Norway as a whole. All inhabitants in the county of Nord-Trøndelag aged 13 and older were invited, and about 75,000 (70%) of those invited participated. Information was collected through comprehensive questionnaires and a clinical examination. A venous blood sample was drawn from attendants above 20 years. The inclusion process is described in detail elsewhere40. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study protocol was approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee in Medicine, Central Norway (project numbers 157–1997 dated 06/11/1997 and 2009.1852 dated 11/20/2009) and the Data Inspectorate of Norway. Informed consent was obtained from all HUNT2 participants.

Data on MI hospitalization was collected from the two primary hospitals in the county of Nord-Trøndelag: Levanger Hospital and Namsos Hospital. From 1995 until 2000 data were registered retrospectively, and from 2001 registration has been done prospectively. The European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology guidelines were used for verification of MI diagnosis. The criteria are elevated troponin T or troponin I together with at least one of the following: (1) symptoms consistent with myocardial infarction and/or (2) ECG changes with development of significant Q wave and/or (3) ECG changes consistent with ischemia (ST segment elevation or depression).

To be eligible for the present study, the participants of HUNT2 had to meet these criteria: available plasma and DNA as well as no previous self-reported cardiovascular disease. 57,133 persons met these criteria. By the end of 2008, 1,689 HUNT2 participants had been admitted with MI and the 370 youngest were selected as cases in the present study. A younger population was particularly selected because the investigated parameters may be less influenced by confounding factors than in an elderly population with comorbidities. Controls matched on age (±2 years) and gender were randomly selected, and all controls were at risk of MI at the time when their corresponding case experienced MI. The same study cohort was described for a previous study investigating polymorphisms in MBL2 and ficolin genes in relation to the risk of MI17.

Clinical variables

Clinical variables such as height, weight and blood pressure were registered as previously described40, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or as diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg, or current use of antihypertensive medication. Information on other medication, such as statins was not available. Concentrations of glucose, creatinine and blood lipids were analysed by standard methods at the General Laboratory at Levanger Hospital. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as total cholesterol >6.2 mmol/L. Smoking was categorized into two groups: never/former or current smokers. The Framingham risk score4 was calculated using the variables in the HUNT2 database (age, HDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive treatment, smoking and diabetes). A positive family history for coronary heart disease was defined as MI before 60 years in a first-degree relative.

Assays

Serum concentrations of ficolin-1, -2 and -3, PTX3, MASP-3 and MAP-1 were determined by sandwich ELISAs using specific in-house produced monoclonal antibodies as previously described13,21,41,42,43,44. All assays were optimized for automated analysis in the 384 well format on Biomek FX (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Statistical analyses

Due to non-normal distribution of several variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate differences in continuous variables. The Chi square test was used to compare categorical variables.

Linear regression with robust standard errors was used to analyse how clinical variables were associated with serum concentration of the biomarkers. The clinical variables included were: age, gender, smoking (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), BMI, diabetes (yes/no), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no) and creatinine. Due to non-normality, either logarithmic transformation or Box-Cox transformation was performed, and extreme outliers were removed from the final models if they substantially altered the results.

Spearman correlation analysis was used to evaluate how the different biomarkers were related to each other. Associations between biomarker concentration and risk of MI were investigated using logistic regression. Biomarkers were divided into tertiles. Traditional risk factors included in the final models were sex, age, hypertension (yes/no), hypercholesterolemia (yes/no), smoking (never or previous/current), diabetes (yes/no) and BMI.

Finally, the improvement in predictive utility was explored with an analysis of the AUC, continuous net reclassification index and integrated discrimination index. Prediction of MI using the Framingham risk score alone was compared to a model combining the Framingham risk score with significant biomarkers from the multimarker analysis.

All tests were two-sided, and results are presented as medians or odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with Stata/MP for Mac, version 11.2, (Stata Corp., College Station, Texas, USA) and R, version 3.2.2 (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Vengen, I. T. et al. Pentraxin 3, ficolin-2 and lectin pathway associated serine protease MASP-3 as early predictors of myocardial infarction - the HUNT2 study. Sci. Rep. 7, 43045; doi: 10.1038/srep43045 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

The HUNT Study is collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine, NTNU - Norwegian University of Science and Technology), Nord-Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Health Authority, and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. We are grateful to the people of Nord-Trøndelag and the personnel at the HUNT Biobank. The Department of Research and Development and clinicians at the Medical Department, Nord-Trøndelag Health Trust, Norway, are acknowledged for their help with data collection and diagnosis validation. The authors also want to thank Mr. Jesper Andresen for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from The Norwegian Council on Cardiovascular Diseases, Novo Nordisk Research Foundation, The Danish Council for Independent Research, Rigshospitalet and The Svend Andersen Research Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions I.V., V.V and P.G. designed the study. I.V. and P.G. performed the laboratory analyses. I.V and V.V. performed the statistical analyses, and T.B.E. contributed to the interpretation of the data. T.B.E. and I.V. drafted the manuscript. V.V. and P.G. revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

References

- Mendis S., Puska P. & Norrving B. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. (World Health Organization, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Das R. R. et al. Prevalence and correlates of silent cerebral infarcts in the Framingham offspring study. Stroke 39, 2929–2935, doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.108.516575 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenja N. et al. Prevalence, extent, and independent predictors of silent myocardial infarction. Am J Med 126, 515–522, doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.11.028 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino R. B. et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 117, 743–753, doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.107.699579 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khot U. N. et al. Prevalence of conventional risk factors in patients with coronary heart disease. Jama 290, 898–904, doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.898 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson G. K. & Hermansson A. The immune system in atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol 12, 204–212, doi: 10.1038/ni.2001 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu F. & Rus H. Complement activation and atherosclerosis. Mol Immunol 36, 949–955 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonacina F., Baragetti A., Catapano A. L. & Norata G. D. Long pentraxin 3: experimental and clinical relevance in cardiovascular diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2013, 725102, doi: 10.1155/2013/725102 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latini R. et al. Prognostic significance of the long pentraxin PTX3 in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 110, 2349–2354, doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000145167.30987.2e (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu W. S. et al. Pentraxin 3: a novel and independent prognostic marker in ischemic stroke. Atherosclerosis 220, 581–586, doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.11.036 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante M. et al. Prognostic and diagnostic potential of local and circulating levels of pentraxin 3 in lung cancer patients. Int J Cancer 138, 983–991, doi: 10.1002/ijc.29822 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri T. et al. Pentraxin 3 in acute respiratory distress syndrome: an early marker of severity. Crit Care Med 36, 2302–2308, doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181809aaf (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastrup-Birk S. et al. Pentraxin-3 serum levels are associated with disease severity and mortality in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. PLoS One 8, e73119, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073119 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauta A. J. et al. Biochemical and functional characterization of the interaction between pentraxin 3 and C1q. Eur J Immunol 33, 465–473, doi: 10.1002/immu.200310022 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y. J. et al. Synergy between ficolin-2 and pentraxin 3 boosts innate immune recognition and complement deposition. J Biol Chem 284, 28263–28275, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009225 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen H. O., Videm V., Svejgaard A., Svennevig J. L. & Garred P. Association of mannose-binding-lectin deficiency with severe atherosclerosis. Lancet 352, 959–960, doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)61513-9 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vengen I. T. et al. Mannose-binding lectin deficiency is associated with myocardial infarction: the HUNT2 study in Norway. PLoS One 7, e42113, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042113 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagowska-Klimek I. & Cedzynski M. Mannan-binding lectin in cardiovascular disease. Biomed Res Int 2014, 616817, doi: 10.1155/2014/616817 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garred P. et al. A journey through the lectin pathway of complement-MBL and beyond. Immuno Rev 274, 74–97, doi: 10.1111/imr.12468 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobo J. et al. MASP-3 is the exclusive pro-factor D activator in resting blood: the lectin and the alternative complement pathways are fundamentally linked. Sci Rep 6, 31877, doi: 10.1038/srep31877 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjoedt M. O. et al. MBL-associated serine protease-3 circulates in high serum concentrations predominantly in complex with Ficolin-3 and regulates Ficolin-3 mediated complement activation. Immunobiology 215, 921–931, doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.10.006 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki D. et al. Small mannose-binding lectin-associated protein plays a regulatory role in the lectin complement pathway. J Immunol 177, 8626–8632 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov V. I. et al. Endogenous and natural complement inhibitor attenuates myocardial injury and arterial thrombogenesis. Circulation 126, 2227–2235, doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.112.123968 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovland A. et al. The complement system and toll-like receptors as integrated players in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 241, 480–494, doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.038 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny N. S., Arnold A. M., Kuller L. H., Tracy R. P. & Psaty B. M. Associations of pentraxin 3 with cardiovascular disease and all-cause death: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29, 594–599, doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.108.178947 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny N. S. et al. Associations of pentraxin 3 with cardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Thromb Haemost 12, 999–1005, doi: 10.1111/jth.12557 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norata G. D., Garlanda C. & Catapano A. L. The long pentraxin PTX3: a modulator of the immunoinflammatory response in atherosclerosis and cardiovascular diseases. Trends Cardiovasc Med 20, 35–40, doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2010.03.005 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolph M. S. et al. Production of the long pentraxin PTX3 in advanced atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22, e10–14 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savchenko A. et al. Expression of pentraxin 3 (PTX3) in human atherosclerotic lesions. J Pathol 215, 48–55, doi: 10.1002/path.2314 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudzik B., Danikiewicz A., Szkodzinski J., Polonski L. & Zubelewicz-Szkodzinska B. Pentraxin-3 concentrations in stable coronary artery disease depend on the clinical presentation. Eur Cytokine Netw 25, 41–45, doi: 10.1684/ecn.2014.0354 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norata G. D. et al. Deficiency of the long pentraxin PTX3 promotes vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 120, 699–708, doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.108.806547 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilely K. et al. Cholesterol crystals activate the lectin complement pathway via ficolin-2 and mannose-binding lectin: implications for the progression of atherosclerosis. J Immunol, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502595 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbati E. et al. Influence of pentraxin 3 (PTX3) genetic variants on myocardial infarction risk and PTX3 plasma levels. PLoS One 7, e53030, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053030 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degn S. E. & Thiel S. Humoral pattern recognition and the complement system. Scand J Immunol 78, 181–193, doi: 10.1111/sji.12070 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yongqing T., Drentin N., Duncan R. C., Wijeyewickrema L. C. & Pike R. N. Mannose-binding lectin serine proteases and associated proteins of the lectin pathway of complement: two genes, five proteins and many functions? Biochim Biophys Acta 1824, 253–262, doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.05.021 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertle E. et al. Distinct longitudinal associations of MBL, MASP-1, MASP-2, MASP-3, and MAp44 with endothelial dysfunction and intima-media thickness: The Cohort on Diabetes and Atherosclerosis Maastricht (CODAM) Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 36, 1278–1285, doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.115.306552 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn M. S. & Klemes A. B. Multimarker approach for identifying and documenting mitigation of cardiovascular risk. Future Cardiol 9, 497–506, doi: 10.2217/fca.13.27 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taqui S. & Daniels L. B. Putting it into perspective: multimarker panels for cardiovascular disease risk assessment. Biomark Med 7, 317–327, doi: 10.2217/bmm.13.15 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Morris N. J., Schaid D. J. & Elston R. C. Power of single- vs. multi-marker tests of association. Genet Epidemiol 36, 480–487, doi: 10.1002/gepi.21642 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmen J. et al. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study 1995–97 (HUNT2): Objectives, contents, methods and participation. Norsk Epidemiologi 13, 19–32 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Munthe-Fog L. et al. Variation in FCN1 affects biosynthesis of ficolin-1 and is associated with outcome of systemic inflammation. Genes Immun 13, 515–522, doi: 10.1038/gene.2012.27 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munthe-Fog L. et al. The impact of FCN2 polymorphisms and haplotypes on the Ficolin-2 serum levels. Scand J Immunol 65, 383–392, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.01915.x (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munthe-Fog L. et al. Characterization of a polymorphism in the coding sequence of FCN3 resulting in a Ficolin-3 (Hakata antigen) deficiency state. Mol Immunol 45, 2660–2666, doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2007.12.012 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjoedt M. O. et al. Serum concentration and interaction properties of MBL/ficolin associated protein-1. Immunobiology 216, 625–632, doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2010.09.011 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]