Large-scale cancer genomics discovery projects, such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) among others, have systematically characterized the molecular lesions in human cancer genomes, thereby laying the foundation for precision cancer medicine. However, a curated set of somatic variants with established relevance to cancer biology is essential for clinical annotation and for use in computational data analysis. We have created DoCM, a Database of Curated Mutations in cancer (http://docm.info), as an open-source, openly-licensed resource to enable the cancer research community to aggregate, store, and track biologically important cancer variants.

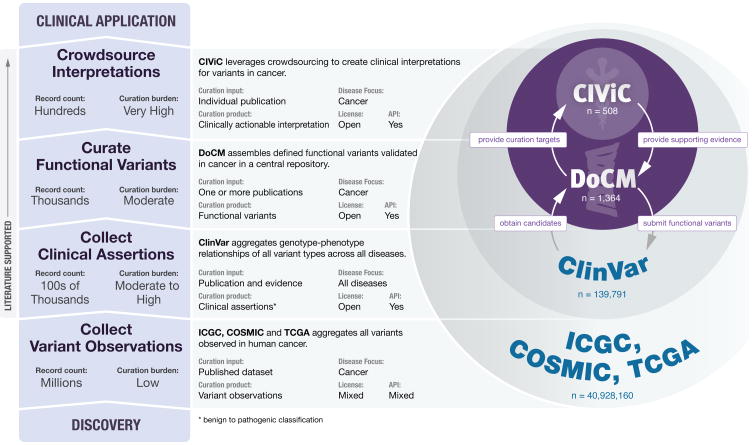

A variety of somatic cancer variant databases exist that help identify important variants, including gene-level 1, variant-level 2,3, and clinically-focused variant interpretation databases 4-6. These resources have greatly increased our understanding of the landscape of clinically and biologically relevant cancer variants, and when used in aggregate provide an understanding of the relevance of specific variants. DoCM is a curated repository that facilitates the aggregation of gene/variant information for variants with prognostic, diagnostic, predictive or functional roles from these resources as well as individually curated publications (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1). The data model and batch submission process (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Figures 2-4) used by DoCM places it at a critical intersection between the two major tradeoffs of curated resources: comprehensiveness of variants and curation burden (Figure 1). In a rapidly changing landscape of genes and variants for which new information is steadily accumulating, an automated batch submission and review system allows DoCM curations to scale easily.

Figure 1. DoCM supports existing curation initiatives while occupying a critical niche that balances comprehensiveness and curation burden.

DoCM accepts variant batch submission of arbitrary size and varying complexity, allowing the resource to be agile and comprehensive. The DoCM data model limits curation burden, while permitting the entry of genes and variants with high quality functional data. DoCM also aggregates functionally important variants from many other quality resources. CIViC, a knowledgebase of clinical interpretations of variants in cancer (http://civicdb.org), is focused on summarizing and aggregating evidence of clinically actionable variants into clinical interpretations. ClinVar aggregates structured variant records and clinical assertions, but has largely been focused on germline variants. Variant observation databases, like ICGC, COSMIC, and TCGA, attempt to report the totality of somatic variants observed in patients to-date. All of these databases are complimentary and inform each other.

Curation of the literature to produce a high quality set of pathogenic somatic variants is not trivial and it is unrealistic that one group could independently keep pace with the ever-expanding cancer genomics literature (Supplementary Figure 5). Hence, we have designed DoCM as an open resource that can coordinate contributions from research and clinical practitioners in cancer genomics. Once important variants are identified, they require significant curation efforts to format and standardize the variants in a structured way for storage and retrieval in a relational database (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figure 6). A set of such curated variants can be contributed to DoCM by batch submission at http://docm.genome.wustl.edu/variant_submission, whereupon they are reviewed and evaluated by DoCM editors for possible inclusion. DoCM is licensed under the creative commons attribution license (CC BY 4.0), allowing academic and industry researchers to freely access the content.

DoCM provides easy access to a current and accurate list of functionally important cancer variants with clear provenance, based on peer-reviewed journal citations. The content of DoCM may be accessed via a web interface or a documented application programming interface (API). To illustrate the utility of DoCM, we performed a focused knowledge-based variant discovery study to identify pathogenic variants missed in 1,833 cases across four TCGA projects (Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figure 7). Validation sequencing data from 93 of these cases showed that at least one functionally important variant in DoCM was recovered in 41% of cases (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Data 1-2, Supplementary Figure 7-9, Supplementary Table 2-4). As genomics evolves into the era of precision medicine and our understanding of the etiology of molecular lesions grows, community curation along with our ongoing efforts will allow DoCM to adapt, refine, and expand with the field.

Supplementary Figures, Tables and Methods

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Lee Trani, Jennifer Hodges, and Aye Wollam who helped with manual review of variant calls. Tim Ley, Ron Bose, Ramaswamy Govindan, and Siddhartha Devarakonda provided valuable input in the curation of DoCM. James Eldred helped oversee the development of the website. David Larson provided valuable input for the analysis performed. MG was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NIH NHGRI K99HG007940). OLG was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NIH NCI K22CA188163). This work was supported by a grant to Richard K. Wilson from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NIH NHGRI U54HG003079).

Footnotes

Author contributions: B.J.A. wrote the manuscript, was responsible for supervising all curation of the literature, initial design of the web interface, testing, creating the knowledge-based variant calling strategy, analysis, initial design of validation sequencing experiment, and figure creation. M.N.K.C, M.G., O.L.G, E.R.M, and A.H.W contributed text and revised the manuscript. A.C.C. designed and implemented the web interface, database, and API. B.J.A., A.C.C., M.G., A.H.W, and J.F.M. made contributions to the code. J.F.M. was the lead user experience web developer. M.G., O.L.G., E.R.M., and A.H.W. provided beta testing feedback. M.N.K.C., J.K., and A.H.W. curated publications to include mutations in DoCM. R.S.F., M.G., O.L.G., and E.R.M. designed and supervised validation sequencing. M.G., O.L.G., and E.R.M. supervised analysis. O.L.G, M.G., E.R.M, and R.K.W provided funding.

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Van Allen EM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing and clinical interpretation of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples to guide precision cancer medicine. Nat Med. 2014;20:682–688. doi: 10.1038/nm.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forbes SA, et al. COSMIC: exploring the world's knowledge of somatic mutations in human cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D805–811. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, et al. International Cancer Genome Consortium Data Portal--a one-stop shop for cancer genomics data. Database (Oxford) 2011;2011 doi: 10.1093/database/bar026. bar026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeh P, et al. DNA-Mutation Inventory to Refine and Enhance Cancer Treatment (DIRECT): a catalog of clinically relevant cancer mutations to enable genome-directed anticancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1894–1901. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dienstmann R, et al. Standardized decision support in next generation sequencing reports of somatic cancer variants. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:859–873. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacConaill LE, et al. Prospective enterprise-level molecular genotyping of a cohort of cancer patients. J Mol Diagn. 2014;16:660–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.