Abstract

Context:

Very few women assume the role of head athletic trainer (AT). Reasons for this disparity include discrimination, motherhood, and a lack of interest in the position. However, data suggest that more women seek the head AT position in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division II and III settings.

Objective:

To examine the barriers female ATs face as they transition to the role of head AT.

Design:

Qualitative study.

Setting:

Divisions II and III.

Patients or Other Participants:

In total, 77 female ATs participated in our study. Our participants (38 ± 9 years old) were employed as head ATs at the Division II or III level.

Data Collection and Analysis:

We conducted online interviews with all participants. They journaled their reflections to a series of open-ended questions pertaining to their experiences as head ATs. Data were analyzed following a general inductive approach. Credibility was secured by peer review and researcher triangulation.

Results:

Organizational and personal factors emerged as the 2 major themes that described challenges for women assuming the role of the head AT. Organizational barriers were defined by gender stereotyping and the “good old boys” network. Personal influences included a lack of leadership aspirations, motherhood and family, and a lack of mentors.

Conclusions:

Female ATs working in Divisions II or III experienced similar barriers to assuming the role of the head AT as those working in the Division I setting. Stereotyping still exists within collegiate athletics, which limits the number of women in higher-ranking positions; however, a lack of desire to assume a higher position and the desire to balance work and home inhibit some women from moving up.

Key Words: sex, leadership, stereotyping, motherhood

Key Points

Motherhood and the desire to have work-life balance inhibit some female athletic trainers (ATs) from moving up to leadership positions in the collegiate athletics setting.

As more women assume leadership positions, such as that of the head AT, potentially more younger women will experience mentorship and seek out these positions as well.

Not all female ATs have professional goals that include the role of the head AT. However, gender stereotyping and the “good old boys” network persist as barriers to the role for those women who do pursue it.

Asteady influx of women has entered the profession of athletic training, with almost 54% of current National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) members being women.1 Several factors have been described as responsible for the marked growth of women in the field, including strong female leaders who have broken down barriers to working within this setting and 3 female NATA presidents.2 Despite the number of female athletic trainers (ATs) employed at the collegiate level and advancement of women within the NATA, women have struggled to attain the position of head AT.2,3 It is estimated that only 19.5% of head AT positions are held by women,3 and many of these positions appear to have resulted from promotion within an organization, rather than an active pursuit of the role.4 Researchers have speculated on the factors inhibiting career advancement for women to the role of head AT, and those who have examined it have linked several interrelated factors to female underrepresentation.

One barrier to advancement for female ATs appears to be low aspirations for leadership or administrative roles, which are strongly influenced by an overall aversion to the duties of the head AT as well as to providing medical care to football players (a role often connected to the head AT position).5 Moreover, female ATs often struggle more than male ATs with the demands related to working in the profession, particularly in the collegiate setting.4,6,7 Working as an AT in the collegiate setting has been described as demanding because the time expectations, numerous changes in work schedules, and frequent travel can make it difficult to balance other roles such as spouse, caregiver, or mom.8 The position of head AT is often synonymous with other leadership positions such as athletic director or school administrator, positions that may increase time demands on the individual assuming the role. For the AT, these demands are often in addition to patient care obligations, which alone can place great strain on the individual. In separate studies, Gorant5 and Mazerolle et al4 found that the position of head AT can seem daunting for women and unappealing due to the effect it may have on one's personal life.

Gorant5 and Mazerolle et al4 focused solely on female head ATs at National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I universities. It has been suggested that more women assume head AT positions in the other collegiate divisions. For example, Acosta and Carpenter3 reported that 36.8% of head ATs in the Division III setting were women. Why more women hold positions in the other levels of the collegiate setting is unknown, as researchers who examined differences among division levels often reported none, particularly in satisfaction and career intentions.9 A recent mixed-methods study10 demonstrated that ATs employed in the non-Division I collegiate setting experienced comparable levels of work-life conflict as ATs in the Division I setting. The ATs employed in the non-Division I setting reported that the number of hours and days they worked, in addition to role overload related to low staffing and number of athletes, negatively affected their work-life balance.10 These findings highlight that challenges related to work-life balance extend beyond the Division I setting. What differentiated ATs in the non-Division I setting, however, was a shortened contract length (less than 12 months), which they felt helped improve work-life balance.10 Although these results suggest that organizational factors compound the work-life balance interface, this may be only a small portion of the problem. A multilevel framework has been suggested within sports as a means to describe the work-life interface, which may influence career advancement and solicitation of leadership positions.11 The framework suggests that sex and cultural ideologies can influence work-life balance and career intentions.11

A decline in female ATs is noted in the profession after the age of 30,7 most notably in the collegiate setting. Despite the multifactorial reasons for the decline, many women persist within the field and assume leadership roles. Those who persist are likely in positions that allow them to satisfactorily and efficiently assume all their roles, which may include mother, caretaker, spouse, and AT.12,13 With that in mind, our purpose was to expand our knowledge of the experiences of women in the role of the head AT, using the work of Mazerolle et al4 as our platform and extending the investigation into the other levels in the collegiate setting. Our study was guided by the following questions:

-

1.

What were the challenges faced by female ATs who were currently employed in the role of the head AT?

-

2.

What barriers existed for the female ATs in the transition to the role of the head AT?

-

3.

What role did the level of competition play in female head ATs' experiences in pursuing and maintaining their leadership positions?

METHODS

Research Design

We used asynchronous in-depth online journaling as a means to gain insights into our female head ATs working in the Division II and III settings. We felt the online platform would provide rich data and a convenient yet confidential means of reaching our targeted population. Online interviewing, via journaling, allows participants the flexibility to complete the interview at their leisure, and this is important for a group of potential participants whose spare time is limited due to involvement in multiple competing roles. We feel confident that this type of interviewing, although devoid of participant and researcher interactions, can produce rich, insightful data as the participants are afforded an extended amount of time to reflect upon the question raised instead of having to respond immediately.14 The institutional review board of the University of Connecticut, Storrs, approved the study.

Participants

A total of 77 female ATs who were employed as a head AT at the Division II or III level participated in our study. They were 38 ± 9 (range, 24−57) years old and had an average of 14 ± 8 (range, 1−33) years of athletic training experience.

Work Life

Our participants worked on average 55 ± 9 (range, 30−75) hours per week, had 11 ± 1 month contracts (range, 9−12 months), and had been in the role of head AT for 9 ± 8 (range, 1−30) years.

Personal Life

Of our 77 participants, 39% (n = 30) were single, 46.8% (n = 36) were married, 9.1% (n = 7) were divorced or separated, and 5.2% (n = 4) did not specify status. Of these women, 35% (n = 27) had children.

Recruitment Strategies

We petitioned the NATA membership database for the names and contact information of those members who were employed at the collegiate level, were women, and self-identified as head ATs (n = 216). This reflected our criterion sample.15 The database is not able to differentiate among the levels within the collegiate setting; so to obtain this information, we sent an e-mail invitation containing a link to a demographic survey via Qualtrics (Provo, UT) to the 216 female head ATs identified by the NATA. To improve our response rate, 2 weeks after our initial request we sent a follow-up e-mail to the contact list. Of the 216 e-mails sent, 140 head ATs responded. Of those 140 responses, 122 women indicated working outside the Division I setting. We recruited from this group.

Data-Collection Procedures

After identifying our sample pool, we sent individual e-mails to the 122 volunteers. Contained within our e-mail was an explanation of the purpose of our study and the request for their voluntary participation. Completing the structured, online interview implied consent. We asked our participants to provide responses to a series of demographic questions that were about their personal (age, marital status, etc) and professional (years as an AT, hours worked per week, etc) experiences. The open-ended portion of the questionnaire was related to their work experiences, perceptions of their role as a head AT, and balancing life and athletic training responsibilities (Appendix). The interview guide was used previously by Mazerolle et al4 to study female head ATs in the Division I setting.

Data Analysis and Trustworthiness

We analyzed our data using the principles of a general inductive process, which allows us to manage in-depth and large datasets.16 Our first step was to evaluate the transcripts holistically by interpretatively reading them, examining them for major findings, and focusing on the meanings of the participants' comments and thoughts. On the second and third evaluations, attention was given to the coding process; we looked for commonalities and repetitive thoughts and experiences related to the female ATs' professional development. We also began to organize our codes within the margins of our transcripts and responses to our questions. Finally, we reevaluated our categorizations and labels, grouping them and determining the frequency of responses, reporting only those findings that represented 50% of our participants' experiences.

To ensure trustworthiness of our data, we used data saturation, a peer review, and multiple-analyst triangulation. As described by Siegle,17 data saturation can be viewed as prolonged engagement, at which point we were unable to uncover any new findings or commonalities in experiences. Our peer reviewer was an outside researcher who has a strong understanding of qualitative analyses and sex and gender concerns in leadership and athletics. Once we had finalized the general inductive analyses, our peer confirmed the analyses. We provided our peer with the transcripts, coding sheets, and our operational definitions of our findings and associated supporting data. Before the review, we triangulated our independent reviews of the data to come to an agreement on the findings.

RESULTS

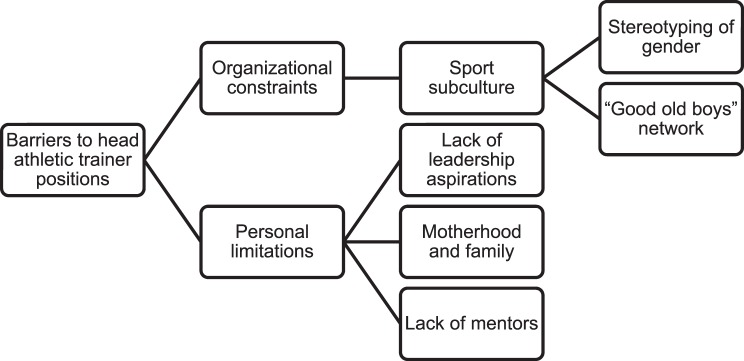

We identified 4 barriers for women seeking or assuming the role of head AT in the Division II or III setting (Figure). Those barriers appeared to originate within either organizational constraints or individual limitations. We describe each barrier with supporting quotes from our participants in the subsequent sections.

Figure.

Barriers to the role of the head athletic trainer for women in the Division II and III settings.

Barriers

Organizational Constraints

The overall theme of organizational constraints reflects the barriers that can manifest within sport organizations, as they pertain to discrimination and views on women in athletics. The constraints emanated from 2 primary areas, the subculture of sport and the network that has developed in which men promote men. These constraints emerge from existing sociocultural influences that suggest women have certain social roles within sport organizations that often do not include managerial or leadership positions. These stereotypes or labeling based on gender often emerge from societal expectations that identify women, unlike men, as not prepared or equipped to handle the rigors of those natural-leader roles.18,19

Sport Subculture

Many of our participants discussed the challenges of the sport subculture as a barrier to the role of head AT. The subculture was described as one that does not support women as leaders, likely due to the ideologies of traditional sex roles, which exclude women from being able to succeed in that role. One participant said, “Let's face it. There is sexism in athletics.” They also commented on coaches and some administrators who took issue with women being in leadership or decision-making positions. One participant explained:

Most of my challenges are from coaches who do not like to acknowledge a female in a position of power. I am the first female head AT at this school, and it did not go over well. The longer I am at the school, the less it is an issue. I am sure most people face a little hostility when taking over a new position. The worst part was having known these coaches for 3 years prior to taking over and them still treating me like garbage just to test me. I feel like I am immediately underestimated because of my appearance (petite female).

Others shared reasons for struggling to assume positions of leadership in college athletics, including “school administrators who didn't want a female AT.” Statements that spoke to sex as a barrier to the role of head AT were focused on the organizational concerns surrounding gender stereotyping and the “good old boys” club that have been used to describe the climate of collegiate athletics.

Stereotyping of Gender

Gender stereotyping emerged from the data as the generalizations that women are unable to complete or fulfill the role of head AT due to their gender. The stereotype was often viewed negatively, as described by 1 female head AT who shared her thoughts on being in a leadership role:

I think there is still a misconception about a woman being able to do the job of a head AT and make the calls that a head AT needs to make, whether that is firing someone or dealing with a catastrophic circumstance. There is still a negative perception about what men can do as versus women.

Another participant highlighted the concept of stereotyping and traditional beliefs about a woman's role:

I believe that society doesn't typically place a female in that role, especially at the collegiate level, because the head [AT] is usually the person to take care of the major male sports. Some administrators feel that men are better suited to take care of men.

Stereotyping was also mentioned by many others, but as noted by another participant, the idea that a woman cannot work in a male sport continues to create an organizational gender barrier in collegiate athletics:

I believe the stereotyping belief that only males can cover football is another reason why females are not given a chance [to be a head AT]. However, if an institution looks at it carefully, a female could be a head and have a separate football coverage, and care can be maintained.

The topic of medical care and the direct link to football and the role of the head AT emerged as part of the stereotyping theme. This was showcased in the previous quote and the statement of another participant:

The first is that these positions [head ATs] are primarily are [sic] held by males for 1 main reason, that position usually works directly with football. The idea of hiring a female to work with football seems to be that of a foreign one still. I am of the position that, if someone can do the job and do it well, it does not matter their sex. It seems that they are allowing female assistants or GAs [graduate assistants] to work with football, but when it comes down to direct responsibility, they are not willing, for whatever reason, to hire a female. I find it difficult to also understand why the head [AT]/director of sports medicine must be the one that works with football.

Our participants consistently described a culture that was rooted in gender inequity and collegiate athletics having a male-dominated subculture. The culture facilitated a “mindset that the male is supposed to be the head athletic trainer.” One female said, “I believe all women in the profession face similar challenges, not identical, but similar.” She depicted the challenges women face in collegiate athletics:

In the male-dominated culture that is athletics, there are many people that have treated me and other women differently than their male counterparts. I don't believe I would have faced some of the situations w[h]ere coaches question me, or speak to me in a certain way, if [I] were not female.

In response to a question regarding having more women assume leadership roles, such as the head AT position, another participant replied, “Remove the stereotype that it is a man's job.” Societal expectations and traditional viewpoints about the role women can play in athletics also shaped the stereotyping of the head AT role.

Good Old Boys Club

The good old boys club was an organizational concern for women navigating the role of head AT. The verbiage referenced the mentality that men in collegiate athletics keep promoting men or male peers and, therefore, women are unable to break into the administrative or leadership ranks. It can be referred to as the male-dominated social network and speaks to the strategic connections men capitalize on to promote other men. One participant shared, “It is a man's world in athletics. You just have to find a way to be one of the guys.” Another participant reflected:

I believe that the stereotype of the good old boys club still exi[s]ts at my current institution. This makes it very difficult, as of the 11 sports that our institution has, there are only 2 female coaches.

Another female head AT explained how this mentality can influence hiring decisions in college athletics:

Good old boy attitude is prevalent in this area. I think, too, that certain administrators are reluctant to hire women, as they might think that they will want to pursue a family someday, and then [leave] her job. That can sway them to hire a male over a female.

Our participants discussed the idea that the limited number of female head ATs is a direct result of the continued favoritism toward men in collegiate athletics. That is, men perceive the role to be a man's job and attempt to continue to hire men into those roles.

Personal Limitations

The theme of personal limitations identifies those barriers that resulted from the woman's own personal values and characteristics. Personal limitations emerged as a result of self-reflection on individual attributes or goals in and out of the workplace.

Lack of Leadership Aspirations

Although our participants were currently in positions of leadership (ie, head ATs), very few had aspired to become a head AT. Common responses or reflections on their “pursuit” or “assumption” of the role included, “I didn't pursue it and didn't want it.” Another participant commented:

I had no aspirations of becoming a head [AT]. I was very happy as an assistant and felt it afforded me the opportunity to practice clinically (work with teams) as well as have some administrative duties.

Many spoke of not “envisioning” themselves as head ATs but taking advantage of opportunities to assume the role. For example, one shared, “Prior to the head position opening, no, I did not envision myself as head athletic trainer.” When asked about her career path, one explained her career trajectory:

Essentially, the person in the position left last October, and I was not ready to leave or report to someone new. I made it known that I would be interested in taking the job. When I originally started as an [AT], I was not interested in becoming a head [AT]. I could only see the extra work and stress that it caused my then boss.

Similar to the previous quote, another participant assumed the role of head AT because of turnover, not active pursuit:

I did not seek a head AT position. I was originally promoted due to a resignation. The university chose to promote me in lieu of doing a search because they eliminated the position I originally held in order to cut salary dollars.

Not wanting the associated stress or responsibility was also a barrier to assuming the role, as another participant described: “I never saw myself as a head trainer because I didn't think I could handle all the responsibility, but I am glad I accepted this position.”

Motherhood and Family

Our participants believed that motherhood was the major roadblock to more women pursuing or being named to the position of head AT. Motherhood as a barrier to career advancement in athletic training was discussed by our participants who were mothers or aspiring mothers and those who had not considered starting families yet. Simply put, our participants, regardless of family status, believed that motherhood played a major role in career planning and decision making. Of our 77 participants, 27 had children, and 22 were married with children. The theme of motherhood can be summarized by 1 comment, the “belief that you can't have family and the career you choose.” Our respondents all had similar thoughts and perceptions as to why women in athletic training were not in leadership roles, such as the head AT. One participant, a mother of 2, said, “I do think that the family situation plays a major reason why females are not in head athletic trainer positions.” A participant who was balancing motherhood and her role as a head AT questioned her future as a head AT:

I just had a baby 3 months ago and returned to work this week. It is a lot of responsibility to be a head [AT], a mom of 2 kids, and a wife. It may be easier to be an assistant [AT], during this stage of my life.

Another participant who was married but did not have children had a similar reflection on women wanting to avoid more work-related responsibilities in order to have more time at home. Interestingly, she also reflected on gender-related roles as a mediating factor in seeking more responsibility at work, such as the role of the head AT:

. . . the family thing, as I think females are more content to take the assistant position, and have more free time. I hear many married [athletic trainers] with children stating that their children are more important than their job. I have met more than a few male [athletic trainers] who value their job over their family.

More details on why motherhood affects the choice to not pursue or assume the role focused on the time commitment needed in athletic training. One participant related her thoughts on the demands of collegiate athletics:

The demands of the job, it is very difficult to work 40 to 60 hours a week plus travel and then to raise a family. The female is usually the primary caregiver, so in the end, she chooses to raise her family over athletics.

The impression that the role of head AT is stressful and a great deal of responsibility was common; coupled with being a mother, this was viewed as a hurdle to more women actively pursuing or remaining in the position of head AT. For example, the next 2 quotes from our participants illustrate this idea of role incongruity:

I think some of it is that females don't want that much responsibility if they have a family to take care of as well. Many females are moms also or aspire to be moms and don't feel they want to take on that much responsibility that will take them away from their children.

Being a head athletic trainer is a lot of pressure, stress, and responsibility. I believe that it is harder for a woman who wants to start or have a family to be a head athletic trainer due to her responsibilities both at home and at work. In order for a woman to be successful as a head athletic trainer, she must have a great support system both at home and at work.

Another woman, who was single, was honest about her career goals once she starts a family. In response to why women are not in head athletic training roles, she wrote:

Family! I know, when I am ready to start a family, I may have to change positions. I hope not, but the reality of it is I will. If you want to have children and actually spend a decent amount of time with them, then being a head athletic trainer is unrealistic.

A married participant said that her lack of work-life balance was a direct reason why she did not start a family. In fact, she likely sacrificed having one to continue in her role as a head AT. She was candid:

Challenges that I face currently is the work-life balance; there does not seem to [be] very much of it in college athletics. I struggle with this on a yearly basis, and yet to figure out how to solve it. I firmly believe that my marriage suffered from a lack of attention to the 12- to 13-hour work days, 7 days a week at work. I wanted to have a family, but that does not feel like an option as women, in athletic training, as a head athletic trainer. If I do take a personal day, I am made to feel guilty for taking time to care for personal matters.

Balancing motherhood and head AT roles was challenging because of the demands of each role; our participants indicated that the role of the head AT is often unyielding and requires time and personal sacrifice. The comments of 1 participant, a married but childless head AT, summarize the idea of motherhood and its influence on career planning. That is, gender norms, traditional ideologies, and individual family values can affect a woman's career plans:

I think, if I were to have children in the future, I would run into a lot of challenges while trying to be a athletic trainer. One challenge I would see myself having is guilt, guilt of not being there as often for my child or guilt that my job is not being done to the standard that I would like or normal[ly] do. Travel would be very hard with teams; to leave your family for a full weekend is difficult, especially when the child is small. I feel that women with families, no matter what occupation, do struggle with the work-life balance, and more often than not, the family wins out, and career is second. I feel that this is much more predominate in athletic training, and most women, when they decide to have a family, they get out of college athletics and move to a work environment that is more conducive to having a family.

Lack of Mentors

The paucity of women in head AT roles was characterized as a barrier to others assuming the role in the future. One participant, who was new to her role and navigating her professional goals, noted, “I have never met a female athletic trainer at the D [Division] III level who was a mother. I have no one to look to or learn from.” She continued to address the effect it could have on her commitment and longevity: “It can be hard to remain focused on my future.” One participant speculated on the low number of women in collegiate athletics:

I would say it may be partly because there were not that many female head [ATs] when I was in school; so we didn't have the role models to look up to and say that we can be in those positions.

Another participant suggested that the low number of females in head AT roles was

. . . partially due to the need for strong female athletic trainers to step up and prove that they can be successful in the role. If someone in a higher position is not seeing the abilities that a female can possess in that role, it may be harder to hire them.

Some comments reflected that, at this time, there were very few women in the head AT position demonstrating a woman succeeding in the role. One participant indicated the influence the lack of females assuming and being retained as head ATs has had on her outlook for the future: “[N]one of my mentors at the college level who are female have children. This is discouraging to me.”

Many of our participants addressed the limited number of role models—that is, women who were currently succeeding in collegiate athletics as head ATs—as a direct contributor to the low numbers. Interestingly, 1 participant identified the impression she could make on future women wanting to be head ATs:

I've spoken with dozens of female ATs who avoid head AT positions or university AT jobs because they assume it's impossible to have a relationship/marriage/family while doing the job. I wonder if I am invisible. I've been married 14 years, and my husband and I have a wonderful, well-adjusted 11-year-old son who grew up in a fantastic environment. I can assure you that those that choose education and/or PT or other non-AT careers for this reason are not better partners/spouses/mothers than me simply because of that reason. If attitudes of women in AT [athletic training] were better, we'd see more women in university leadership positions.

DISCUSSION

A paucity of women in leadership positions is common in many professions but is often highlighted within collegiate athletics as a male-dominated environment.3,5 Researchers20,21 have identified several common barriers to role advancement, including gender and role stereotyping, the good old boys club, hiring and recruitment practices, and dual-earning career couples. Much like Mazerolle et al,4 we found comparable barriers (ie, sex, motherhood) to the role of the head AT position. Expanding upon the work of Mazerolle et al,4 we observed that barriers to the role of the head AT in the Division II or III setting can be attributed to organizational influences, including stereotyping. We also learned, however, that many individual factors, such as motherhood, lack of leadership aspirations, and the scarcity of female mentors, create barriers to women assuming the role of the head AT.

Roadblocks to women advancing to leadership or administrative roles have often been linked to gender role theory, which suggests that women are not equipped to succeed because they are not wired to successfully navigate the expectations associated with the roles.22 Underrepresentation of women in leadership roles is evident in collegiate athletics, especially within athletic training, where only a small percentage of those women are in positions of leadership (ie, head AT). As our participants described, gender discrimination continues to contribute to exits from collegiate athletics, which supports the results of other researchers,4,5,23,24 and gender discrimination limits the advancement of women into roles of leadership.

Societal norms have driven the dogma that women should “take care of” and men should “take charge”; this has led to the bias that women cannot hold leadership roles.25 Several of our participants shared their challenges in assuming the head AT position, as administrators were reluctant to hire a woman. Despite the number of female head ATs in the Division II and III settings being larger than in the Division I setting, organizational barriers such as those identified by Mazerolle et al4 do exist. Discussions of sexism, stereotyping, and the good old boys club permeated our data and speak to major barriers to career advancement for women in male-dominated professions: prejudice against women due to preconceived stereotypes of traditional role assignments and the appropriateness of their assuming these conventional roles.26,27

Often, the ideal leader is decisive, assertive, and independent, traits that parallel those of the “ideal man.” In contrast, women are supposed to be nice, caretaking, and selfless. Psychologists talk about 2 sets of qualities: communal and agentic. Communal qualities are linked with compassion, sympathy, kindness, sensitivity, and gentleness, all qualities typically associated with women. Agentic qualities are linked with ambition, self-confidence, aggressiveness, forcefulness, and assertiveness, all qualities associated with men. Agentic traits are also associated with the qualities of a leader. The dichotomy between traditionally feminine qualities and the qualities thought necessary for leadership places female leaders in a double bind. Behaviors that suggest self-confidence or assertiveness in men often appear arrogant or abrasive in women. Meanwhile, women in positions of authority who display a conventionally feminine style may be liked but not respected. They are deemed too emotional to make tough decisions and too soft to be strong leaders. Consider performance feedback as an example of the double bind women face. Research28−30 has shown that accomplished, high-potential women who are evaluated as competent managers often fail the likability test. Conversely, competency and likability tend to go hand in hand for similarly accomplished men.

A possible explanation for this double bind can be found within role congruity theory. Role congruity theory22 predicts that women will be less likely than men to emerge as leaders when expectations for the leader role differ from gender stereotypes. Eagly and Karau22 developed this theory, which proposes that a group will be positively evaluated when its characteristics are recognized as matching the typical societal norms. According to this theory, prejudice toward female leaders occurs because of inconsistencies between traditional female stereotypes and those associated with successful leaders.

According to Eagly and Karau,22 this incongruity between leadership roles and traditional female roles can lead to 2 forms of prejudice: (1) viewing women as potential leaders less favorably than men and (2) judging behavior that is typical of successful leaders less favorably when performed by a woman. A consequence is that attitudes are less positive toward women than men as leaders and hypothetical leaders. It may therefore be more difficult for women to become leaders and to achieve success in leadership roles. Role congruity helps to explain how macro-level constructs can impede a woman's ability to attain and succeed in leadership roles.

Interestingly, despite the larger number of women assuming leadership roles outside the Division I setting, our participants indicated that a roadblock to these positions coincides with a lack of desire or aspiration for higher rank. Gorant5 identified this barrier in athletic training, and as we noted in our participants, Mazerolle et al4 too found that women in athletic training did not necessarily foresee themselves becoming head ATs. In many cases, similar to those in the Mazerolle et al4 study, our participants were given opportunities to assume the role of the head AT through retirement, departure, or other circumstances. So although many organizational barriers do exist, individual factors, such as lifestyle preferences or personality, may also influence a woman's career planning and experiences navigating a career in athletic training. A lifestyle that is viewed as adaptable appears to be more favorable to women31,32; that is, they want careers that allow for a balance between work and home life. Perhaps, this desire drives a female AT to avoid seeking leadership roles because she is concerned that they will not afford enough flexibility and time to create an adaptive lifestyle.31,32 As we did, Gorant5 found that active mentoring is deficient for many women and may serve as a hindrance to others wanting to serve in this role. As a result, the perception that women cannot assume leadership roles is implied, and the numbers continue to remain low.

Another barrier unique to the athletic training literature was the lack of mentors for our participants. Our respondents shared that very few women are in head AT positions, which indirectly serves as a barrier to career advancement. That is, because they were not mentored by female ATs serving as leaders, they received a message that women cannot succeed in the role or do not want the role altogether. This is an interesting finding, as within the mentoring literature, the sex of the mentor has not been linked to a successful relationship.33 Possibly, our participants drew upon the idea of observation in social learning theory.34 That is, behaviors may be driven by reinforcement, and in our case, a lack of reinforcement due to a limited number of women working as head ATs in the collegiate setting. Although this is partly true, as observed by Gorant5 and Mazerolle et al,4 women tend to be cautious in seeking leadership roles, which can often bring added stress and responsibility and are often linked to sport assignment (that is, the head AT is often the person working with the football team). Parallel to Gorant,5 our participants discussed gender, lack of aspiration, and lack of mentors for the primary medical care assignments (football) as barriers for women.

Motherhood has also been described as a barrier to career advancement and climbing the administrative ladder.21 The barrier emerges as a byproduct of what is described by Hakim31 as a lifestyle preference that is adaptive and based on a desire to balance paid work and family time. The responsibility for rearing children, along with other domestic care responsibilities, has remained with the mother, which serves as the catalyst to halt career advancement or prompt reconsideration of career goals. The barrier of motherhood for our participants was a manifestation of both organizational factors (hours worked, work schedules) and individual facets (personality, family values). Simply, they acknowledged that the time constraints and work demands associated with athletic training, not including the increase in administrative responsibilities, severely limit the time and energy available to take care of their family and personal needs. Being childless was a catalyst for the female head ATs in the study by Mazerolle et al4 of the Division I setting. Successful navigation of the role of the head AT was possible because the women could focus on the pursuit and completion of those time-consuming aspects of the job and did not need to care for their families. That description was best supported by 1 of our participants, who had just given birth to her second child and was considering her longevity in the head AT role, as balancing both seemed to be unmanageable.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Our data were presented from the perspective of the female AT, and in our study and Mazerolle et al,4 the concept of gender stereotyping was discussed as a major barrier. This finding is from the perspective of only female head ATs; thus, future authors should investigate whether administrators are reluctant to hire female ATs for the reasons cited in this study. Several organizations exist in collegiate athletics to help support the growth and development of women leaders as well as those who aspire to serve in leadership roles. Perhaps studying the successes and the influence these organizations (eg, Women's Sports Foundation, National Association of Collegiate Women Athletics Administrators) have on female leaders in collegiate sports will encourage women to overcome the barriers we identified.

Using an online platform to collect our data was fruitful, as it allowed us to obtain a larger sample than would be possible in the traditional qualitative research study. However, we could not follow up with each of the participants regarding their responses or experiences. Although data saturation was reached and our sample was robust for a qualitative study, a more in-depth look at these barriers could assist in the development of effective strategies to circumvent these concerns. Moreover, authors who have examined women in leadership roles within athletics have used other platforms that allow interactions (focus groups) among the participants, which has afforded them the chance to expand upon their thoughts and corroborate those experiences.

Finally, we surveyed women currently serving in the role of head AT within these settings, and their experiences showcased the need for mentoring and continued support of women who aspire to become leaders. Future researchers should attempt to capture the experiences of women early in their careers, particularly as they develop their career plans and aspirations. It is possible that, if mentoring occurs early and opportunities to develop leadership skills are available, more women will seek and persist in these roles.

CONCLUSIONS

Women in athletic training face gender bias and discrimination,4,24,35 and these challenges appear to create barriers to career advancement and promotion into head AT roles. A lack of mentors or role models emerged as a barrier for our participants. That is, they believed that the scarcity of women in head AT roles is because of a deficiency of women seeking, assuming, and remaining in the position. This is interesting because Eddy and Cox26 demonstrated a direct link between being mentored and women advancing up the administrative ladder. Within athletic training, Pitney et al33 suggested that mentors are fundamental to helping the AT navigate the bureaucracy in collegiate athletics. Thus, as more women successfully assume the role of head AT and are able to mentor others, more will likely be promoted. Quite possibly, early mentoring for female ATs may be necessary, and like the organizations that currently exist to support the growth of women who want to be leaders in sports, athletic training may too want to create such an informal or formal support network.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Laura Burton, PhD, and John Borland, PhD, for their roles as peer reviewers.

Appendix. Interview Questionsa

-

1.

Can you explain and describe how you got to your current position, starting with your education and all the jobs you have held since then until now?

-

2.

Why did you pursue the position of head athletic trainer?

a. Before you became a head athletic trainer, did you envision yourself as a head athletic trainer? If yes, why? If not, why not?

b. What experiences prepared you for your role of head athletic trainer?

c. Have there been people in your life that have helped you reach the position of head athletic trainer?

-

3.

What challenges have you faced in the pursuit of your career goals?

a. Are these challenges similar to others in your current position?

b. What challenges have you faced based upon your gender?

-

4.

What challenges have you faced in your position as a head athletic trainer?

a. Have your challenges reflected the level of intercollegiate athletics?

-

5.

Why do you think the numbers are low for females to assume the role of the head athletic trainer? Or why do you think the percentages are not more equitable concerning male vs female?

-

6.

What advice would you give to female athletic trainers who have aspirations to pursue the head athletic trainer position?

-

7.

What factors do you believe influence an athletic trainer's pursuit of the role of head athletic trainer? Do you think these factors are different based on gender?

-

8.

In your opinion why are there a limited a number of female athletic trainers in the position of head athletic trainer?

-

9.

What changes do you think need to be made to increase the number of women in head athletic trainer positions?

-

10.

What changes need to be made on an organizational level to encourage more women to pursue these jobs?

-

11.

How can athletic administrators influence this gendering practice?

a Adapted with permission and presented unedited. Mazerolle SM, Burton LJ, Cotrufo RJ. The experiences of female athletic trainers in the role of the head athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2015;50(1):71−81.

REFERENCES

- 1. Membership statistics. National Athletic Trainers' Association Web site. http://members.nata.org/members1/documents/membstats/index.cfm. Accessed February 23, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Martin L. The role of women in athletic training: a review of the literature. Skyline: Big Sky Undergrad J. 2013;1(1):13. http://skyline.bigskyconf.com/journal/vol1/iss1/13/?utm_source=skyline.bigskyconf.com%2Fjournal%2Fvol1%2Fiss1%2F13&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages. Accessed February 23, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Acosta RV, Carpenter LJ. Women in intercollegiate sport a longitudinal, national study: thirty-seven year update: 1977–2014. Women in Sport Web site. http://www.acostacarpenter.org. Accessed February 23, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mazerolle SM, Burton LJ, Cotrufo RJ. The experiences of female athletic trainers in the role of the head athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 1: 71– 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gorant J. Female Head Athletic Trainers in NCAA Division I( Football IA) . Athletics: How They Made it to the Top [dissertation]. Kalamazoo: Western Michigan University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Naugle KE, Behar-Horenstein LS, Dodd VJ, Tillman MD, Borsa PA. Perceptions of wellness and burnout among certified athletic trainers: sex differences. J Athl Train. 2013; 48 3: 424– 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kahanov L, Eberman LE. Age, sex, and setting factors and labor force in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2011; 46 4: 424– 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mazerolle SM, Ferraro EM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Factors and strategies that contribute to work-life balance of female athletic trainers employed in the NCAA Division I setting. Athl Train Sport Health Care. 2013; 5 5: 211– 222. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Terranova AB, Henning JM. National Collegiate Athletic Association division and primary job title of athletic trainers and their job satisfaction or intention to leave athletic training. J Athl Train. 2011; 46 3: 312– 318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Eason CM. Experiences of work-life conflict for the athletic trainer employed outside the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I clinical setting. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 7: 748– 759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Work-family conflict in coaching I: a top-down perspective. J Sport Manage. 2007; 21 3: 377– 406. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mazerolle SM, Gavin K. Female athletic training students' perceptions of motherhood and retention in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2013; 48 5: 678– 684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mazerolle SM, Goodman A. ATs with children: finding balance in the collegiate practice setting. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2011; 16 3: 9– 12. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mann C, Stewart F. The online interviewer. : Internet Communication and Qualitative Research: A Handbook for Researching Online. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications; 2005: 152. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pitney WA, Parker J. Qualitative Research in Physical Activity and the Health Professions. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thomas D. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006; 27 2: 237– 246. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siegle D. Trustworthiness. University of Connecticut Web site. http://researchbasics.education.uconn.edu/trustworthiness/. Accessed February 23, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Parks JB, Russell RL, Wood PH, Robertson MA, Shewokis PA. The paradox of the contended working woman in intercollegiate athletics administration. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1995; 66 1: 73– 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lovett DJ, Lowry CD. “Good ol boys” and “good ol girls” clubs: myth or reality? J Sport Manage. 1994; 8 1: 27– 35. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eagly AH, Carli LL. Through the Labyrinth: The Truth About How Women Become Leaders. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Booth CL. Certified Athletic Trainers' Perceptions of Gender Equity and Barriers to Advancement in Selected Practice Settings [dissertation]. Grand Forks: University of North Dakota; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev. 2002; 109 3: 573– 598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ohkubo M. Female Intercollegiate Athletic Trainers' Experiences With Gender Stereotypes [master's thesis]. California: San Jose State University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Burton LJ, Borland JF, Mazerolle SM. “They cannot seem to get past the gender issue”: experiences of young female athletic trainers in NCAA Division I intercollegiate athletics. Sport Manag Rev. 2012; 15 3: 304– 317. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Galloway BJ. The glass ceiling: examining the advancement of women in the domain of athletic administration. McNair Scholars Research Journal. 2012;5(1):6. http://commons.emich.edu/mcnair/vol5/iss1/6/?utm_source=commons.emich.edu%2Fmcnair%2Fvol5%2Fiss1%2F6&utm_medium=PDF&utm_campaign=PDFCoverPages. Accessed February 23, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eddy PL, Cox EM. Gendered leadership: an organizational perspective. New Dir Community Coll. 2008; 142: 69– 79. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Whisenant WA, Pedersen PM, Obenour BL. Success and gender: determining the rate of advancement for intercollegiate athletic directors. Sex Roles. 2002; 47 9−10: 485– 491. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lyness KS, Thompson DE. Above the glass ceiling? A comparison of matched samples of female and male executives. J Appl Psychol. 1997; 82 3: 359– 375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Budig M. Male advantage and the gender composition of jobs: who rides the glass elevator? Soc Problems. 2002; 49: 258– 277. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Eagly AH, Carli LL. Women and the labyrinth of leadership. Harv Bus Rev. 2007; 85 9: 62– 71, 146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Women, Hakim C. careers, and work-life preferences. Br J Guid Counsel. 2006; 34 3: 279– 294. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hakim C. Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century: Preference Theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pitney WA, Ehlers GE, Walker SE. A descriptive study of athletic training students' perceptions of effective mentoring roles. Inter J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2006; 4 2: 1– 8. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bandura A, Walters RH. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mazerolle SM, Borland JF, Burton LJ. The professional socialization of collegiate female athletic trainers: navigating experiences of gender bias. J Athl Train. 2012; 47 6: 694– 703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]