Abstract

Context:

Motherhood has been identified as a barrier to the head athletic trainer (AT) position. Role models have been cited as a possible facilitator for increasing the number of women who pursue and maintain this role in the collegiate setting.

Objective:

To examine the experiences of female ATs balancing motherhood and head AT positions in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division II and III and National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics settings.

Design:

Qualitative study.

Setting:

National Collegiate Athletic Association Divisions II and III and National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics.

Patients or Other Participants:

A total of 22 female head ATs (average age = 40 ± 8 years) who were married with children completed our study. Our participants had been certified for 15.5 ± 7.5 years and in their current positions as head ATs for 9 ± 8 years.

Data Collection and Analysis:

We conducted online interviews with all participants. Participants journaled their reflections on a series of open-ended questions pertaining to their experiences as head ATs. Data were analyzed following a general inductive approach. Credibility was confirmed through peer review and researcher triangulation.

Results:

We identified 3 major contributors to work-life conflict. Two speak to organizational influences on conflict: work demands and time of year. The role of motherhood, which was more of a personal contributor, also precipitated conflict for our ATs. Four themes emerged as work-life balance facilitators: planning, attitude and perspective, support networks, and workplace integration. Support was defined at both the personal and professional levels.

Conclusions:

In terms of the organization, our participants juggled long work hours, travel, and administrative tasks. Individually and socioculturally, they overcame their guilt and their need to be present and an active part of the parenting process. These mothers demonstrated the ability to cope with their demanding roles as both moms and head ATs.

Key Words: mentorship, work-life balance, gender

Key Points

This group of female head athletic trainers who were also mothers experienced conflicts among their roles.

They coped with these demanding roles by planning, being adaptable, relying on support, and integrating the roles.

Having a realistic but positive attitude reduced stress and improved their outlook.

Women have long faced the challenge of balancing work and family. Despite recent reports that suggested men face similar burdens as women do, a 2013 Pew Research survey1 indicated that women were still 3 times more likely than men to face hardships. Hardships may stem from role overload, feelings of guilt about and responsibility for the household, domestic and child-rearing duties, and work-related expectations and the need for balance. Ninety percent of working mothers reported experiencing conflict while trying to balance their personal, family, and work demands and responsibilities.2 The conflict is often stimulated by a host of factors, including organizational constraints, which may include time spent at work (38% of working mothers spend 50+ hours per week at work1), travel requirements, the need to be present (“face time”) to complete work tasks, and inflexible work schedules.3,4 Conflict is also exacerbated by a variety of individual contributors, such as the need to parent and complete household responsibilities such as cooking, cleaning, laundry, and other domestic tasks.3–6 Work-life conflict does not result from a single factor (eg, working too much) but from a multitude of interconnected elements, such as the workplace climate, job-related responsibilities, and the individual's family values and beliefs.

Over the last 5 years, attention to the work, life, and family interface has increased within athletic training.7–10 The concerns have manifested for many reasons but largely because of relationships identified between professional attrition and work-life conflict.8–10 In a recent study of burnout and general wellness, Naugle et al11 found that female athletic trainers (ATs) struggled with balancing multiple demanding roles, such as parenthood and athletic training. Kahanov et al12 suggested that female ATs are departing the profession at a quicker rate than male ATs because of challenges from balancing the roles of an AT and mother. Although male ATs also experience and report conflicts, female ATs may perceive them to be of greater concern and a reason to depart.11,12 The work setting has also stimulated this departure for ATs: the collegiate setting has seen a marked decline in female versus male ATs.10,12 The sport culture, and collegiate athletics in particular, is known for long, irregular hours that often extend beyond a 40-hour workweek into the nighttime and weekends.13 Furthermore, the sport culture is heavily rooted in the concept of face time,14 which describes the importance of being visible and available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week to fulfill work-related responsibilities and expectations. The need for face time leads to inflexible work scheduling, confounding the individual's ability to find balance. Mazerolle et al15 suggested that female ATs make the choice to leave the collegiate setting and, at times, the athletic training profession because of the long hours worked and the strain they place on the ability to succeed in the roles of both mother and AT.

The concept that success in one role (eg, AT) limits success in another role (eg, mother) has emerged as a reason to not pursue a leadership role within athletic training.16 Although work-life enrichment is increasingly recognized as a benefit of working while simultaneously engaging in a parental role,17,18 athletic training leaders do not seem to be helped by this benefit.16 Over the last few decades, Acosta and Carpenter19 have demonstrated a marked difference in the number of women in leadership roles, particularly in athletic training (eg, head AT role). Many women seem to shy away from leadership roles in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting, but more assume these roles in non–Division I settings,19 and motherhood has been suggested as a major reason.16 Although the Division I setting has been described as demanding and grueling, the atmosphere of the non–Division I setting (ie, Divisions II and III and the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics) has been depicted as more balanced and less stressful because of more reasonable expectations related to performance, revenue, and academic standards.20 This reason, among others, may attract more female ATs to seek and remain in leadership roles despite becoming mothers.

The purpose of our study was to gain an appreciation for the experiences of working mothers balancing the roles of AT and leader by serving as head ATs in the non–Division I setting. We specifically focused on the challenges mothers face regarding work-life balance and the strategies they use to balance the demands on them as working mothers. We believe this is important because Mazerolle et al16 suggested that motherhood appears to be a major barrier to assuming a head AT role within the Division I setting; according to Acosta and Carpenter,19 only 17.5% of all Division I head ATs were women. The total percentage of female head ATs was 30.7%, but a majority of these women were in the Division II or III setting. Thus, the barrier of motherhood may be less challenging in these settings than in the Division I setting. Our study was guided by the following questions: (1) Which factors contribute to conflicts between work and home life for the female head AT who is also a mother? (2) What strategies can help to facilitate a balance between work and home life?

METHODS

Research Design

We used a phenomenologic design to examine the experiences of female ATs serving as head ATs in the collegiate setting outside of Division I. The central premise of phenomenologic research is to intentionally understand the collective experiences of individuals who share a similar phenomenon.21 In our case, we were concerned with how our participants balanced their roles as mothers, ATs, and leaders within their sports medicine departments (head ATs). Phenomenologic research is based on the descriptive meanings that are often gathered in an interview format structured around the phenomenon being studied. Although traditional research uses the one-on-one interview, we used an online medium as a means to collect information about our participants' lived experiences. No prescribed way of interviewing has been documented in the literature22,23; however, key fundamentals must be present for the participants to share their experiences through openness and reflection.23 We created open-ended questions that avoided directing or guiding but rather allowed participants a platform to share their personal opinions and experiences.

Participants

A total of 22 female head ATs (average age = 40 ± 8 years) who were married with children completed our study. Our participants had been certified for 15.5 ± 7.5 years and in their current positions as head ATs for 9 ± 8 years. Most of our participants were employed via 11-month contracts (range = 9–12 months), and they worked on average 50 ± 9 hours per week. For the purposes of this study, we specifically targeted mothers who were female head ATs employed in the non–Division I setting.

Data-Collection Methods

Instrument Development

Before obtaining institutional review board approval, we developed a structured interview guide. The first set of questions was closed ended and designed to gain demographic information, including age; years of experience; position type; and other personal (eg, marital status), institutional, and organizational (eg, hours worked, travel) variables. The second set of questions was open ended and focused on participants' experiences as mothers, ATs, and leaders or managers. The questions were derived from the previous literature15 and our intended purpose of the study. We also borrowed questions from Mazerolle et al,16 who investigated the experiences of female head ATs in the Division I setting (Appendix). We conducted a peer review of our instrument with a female AT who had published extensively in the area of qualitative methods and professional topics such as retention and work-life balance. Then, before data collection, we had 2 female head ATs with children pilot the study. They were instructed to complete the study's outlined procedures, and then we solicited feedback individually through e-mail to make any changes they believed necessary. All comments involved grammar or the flow of questioning; appropriate edits were made before launching the study.

Recruitment and Procedures

From the National Athletic Trainers' Association membership database, we solicited the names and contact information of those members who were women employed at the collegiate level and identified as head ATs (N = 216). The National Athletic Trainers' Association database does not differentiate among the divisions within the collegiate setting, so we sent an e-mail invitation containing a link to a demographic survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) to the 216 female head ATs. Two weeks after our initial request, we sent a follow-up e-mail to the contact list. Of the 216 e-mails sent, 140 head ATs responded. Of those 140 responses, 18 indicated that they worked in the Division I setting, with 122 women employed in other divisions.

We then sent individual e-mails to those women who had identified as working in the Division II, Division III, or National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics setting (n = 122). Our e-mail explained the purpose of our study and asked for their voluntary participation in the online interview. Interested individuals clicked on the icon provided within the e-mail and proceeded to a series of open-ended questions regarding their experiences as an AT and a head AT. Consent was implied by completing the structured online interview. A total of 77 participants completed the survey, of whom 22 met our criterion of being married with children.

Data Analysis

We followed the process for phenomenologic data analysis as prescribed by Colaizzi24:

-

1.

A general analysis of the transcript data was performed through a cursory reading of each interview.

-

2.

On the second reading of each transcript, specific statements regarding the phenomenon under study were identified and labeled.

-

3.

Labels were based on meaning and context as they pertained to the phenomenon.

-

4.

The labels were evaluated and then grouped, according to meaning, with other labels within each individual transcript.

-

5.

The final presentation of the data was representative of the phenomenon and included an extraction of textual data.

-

6.

We validated the findings by engaging in researcher triangulation and peer review.

Credibility

Both authors are female ATs who have worked in the non–Division I collegiate setting. To address any potential bias, we independently disclosed any potential concerns to each other to help ensure the trustworthiness of the data. Although both authors worked in the collegiate setting, neither of us held the position of head AT. Both authors experienced challenges related to work-life balance in our professional careers. Any biased results would not benefit our attempts to better understand the influence of motherhood on female head ATs. Therefore, any potential bias was checked against our strong desire to objectively understand the perceptions of the participants. However, it was important for us to maintain a high level of sensitivity to subjectivities by using a team approach. Additionally, we used the strategy of bracketing25 to demonstrate validity of the data-collection and analysis process and to reduce the risk of researcher bias. The process allowed us to remove our previous beliefs and experiences as much as possible in order to fully appreciate the experiences of our participants. The bracketing process began with the initial conception of the structured interview guide and the purposeful selection of the online data-collection method. We prepared the interview guide in an open-ended format to engage in each participant's reflection on her experiences and not direct her. We also had 2 female ATs, a sport management researcher, and an athletic training researcher review the interview guide before implementation. This review was calculated, as we hoped to reduce researcher bias and avoid leading our participants to respond in a specific way. Although the online interview reduced our ability to follow up, it allowed our participants to share their feelings confidentially.26

In addition to the bracketing technique, to secure credibility, we used a peer-review process and researcher triangulation. The peer was an independent researcher who was trained in qualitative methods and currently works as an AT. Her perspectives provided a stakeholder check as we navigated the analysis process. Upon completion of the phenomenologic analyses, we shared our findings with the peer to gain triangulation. We conducted the analyses independently and then discussed the results by sharing coding sheets and extracted data to support the emergent findings. This process yielded agreement and the findings presented in the subsequent section.

RESULTS

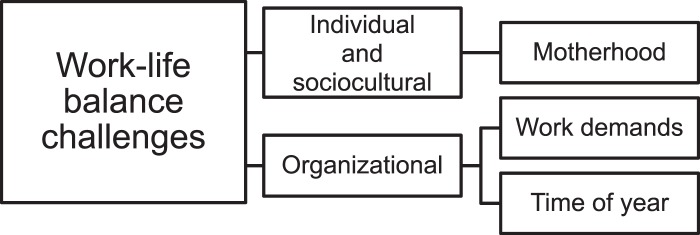

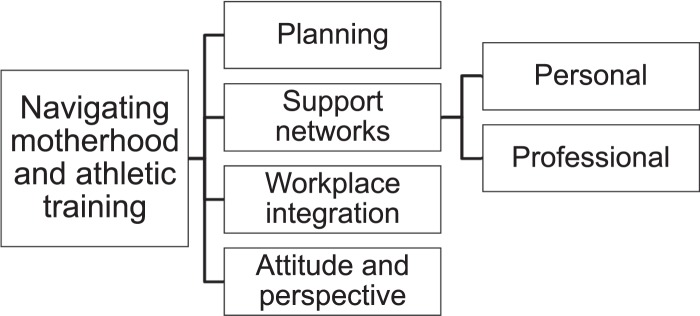

We identified 3 major contributors to work-life conflict (Figure 1). Two speak to the organizational influences on conflict: work demands and time of year. The role of motherhood was more of a personal contributor that precipitated conflict for our ATs. Our data analysis also revealed 4 major strategies (Figure 2) used by female ATs balancing motherhood and the role of head AT in the non–Division I setting. When in place, the strategies we present helped our female ATs create a balance among the roles of mother, AT, and supervisor (head AT). We present the findings with supporting quotes from our participants.

Figure 1. .

Challenges facing female athletic trainers balancing motherhood and head athletic trainer positions.

Figure 2. .

Strategies used to balance motherhood and athletic training.

Inhibitors of Work-Life Balance

Asked to describe their work-life balance, respondents candidly illuminated experiences of conflict as they tried to juggle their roles as head ATs and mothers. Comments included simple responses such as “work-life balance??? If I figure out any of that I will let you know”; “I would say work unfortunately comes first more often, but I am trying to work on that”; “life balance is in the negative”; and “the balance is poor.” Other participants provided greater details of their struggles to find time to balance their lives. Conflicts were stimulated primarily by 2 organizational factors: work demands and the time of year, but we identified 3 factors in our participants' responses that they felt contributed to their experiences of imbalance: (1) motherhood, (2) work demands, and (3) time of year.

Motherhood

Our participants shared their struggles with balancing their roles as working mothers. That is, assuming the role of mother in addition to the role of head AT can be challenging and stimulate conflict. One AT said candidly, “Being a mom is hard enough without the amount of time we spend in the athletic training room and with team practice and game schedules. If we have to travel too, that increased the burden.” Other comments regarding the effect of motherhood and athletic training on work-life balance were “not just being a head athletic trainer, but in general being an athletic trainer and mother has impacted the time I have to spend with my family”; “I have been in athletic training for 25 years, my kids are in their last year as elementary students, I wish I could have been able to be involved more, but I couldn't”; and “I miss my daughter growing up from August to May. I miss soccer games, school activities.”

In addition to their absences from school and extracurricular activities, many of our participants shared their guilt regarding work and family time. That is, the motherhood role added feelings of guilt because they could not be in 2 places at once. Several participants shared, “my biggest challenge is feeling guilty”; “I experience challenges like all working mothers do, guilt time”; and “my biggest challenge is having to cover athletic events when my own children are playing sports. I am not able to watch their games, as I am instead taking care of other people's children—that is hard.”

Work Demands

Our respondents noted that hours worked and travel were their primary facilitators of work-life conflict. One AT stated, “My work-life balance is very poor. I spend about 70 hours a week at work, leaving me exhausted and not wanting to participate in any activities outside of work.” Another had a similar comment about the number of hours worked per day: “balance is poor, as I work at least 13-hour days during the [academic] year.” Many others also journaled about their struggles with long work days and weeks. For instance, one AT responded to a question about her current work-life balance: “it is very difficult as I work at least 11-hour days, if not more sometimes. It's mainly work and a little bit of life.”

Time of Year

Several participants illustrated the struggle with the ebbs and flows of the year and their effects on work-life balance. During certain times of the year, work demands are high and life has to be placed on hold. For example, one AT wrote, “work-life balance can be horrible, especially during the months of August through November. The spring is better, but it's the best during June and July.” The day-to-day demands on the AT during the academic year were evident in an AT's reflections on work-life balance. She observed, “I do not have a balance. I am too busy with work, getting harassed at work. So my work-life balance only exists in the summer.” Another woman described the constraints of the non–Division I setting with regard to time of year: “It is tough [to find balance] when at a small school, working multiple sports so I am in season from August to June. There really isn't any downtime to take advantage until the summer.” Another AT highlighted the relationship between work demands and time of year, sharing her struggles with work-life balance. She commented,

I definitely work a lot of hour[s] (50–70 per week), so the “life” part is greatly impacted. There is always an ebb and flow to the year. I do have greater balance during the summer months compared to the fall/winter.

Many of our participants also indicated that their contracts were 12-month appointments, so although patient-care responsibilities were reduced during the summer, they continued to have other requirements and obligations to manage.

Facilitators for Work-Life Balance

Despite challenges with finding work-life balance, our ATs used various strategies to find work-life balance (Figure 2). The tactics were mostly on the individual level (planning, attitude), but others were on an organizational level (eg, support networks, workplace integration). In combination, they helped to establish work-life balance.

Planning

Our participants discussed the importance of planning and being organized as a means to fulfill the roles of mother, AT, and supervisor. One shared the need for organization and planning within both domains: that is, knowing what needs to be done and when help can create balance. She addressed her strategy to find balance, saying,

I have a structured schedule both at work and home. That seems to work for everyone. There are always schedule changes that come up, but for the most part we have on what is going on each [day] of the week who is doing what at both home and at work. I consider myself extremely organized, which helps.

A similar strategy was used by another participant, whose mantra was “Plan, plan, plan.” She continued, “I try to know my schedule 2 weeks or more in advance, if something comes up unexpected than I make arrangements.” Another woman described the need to plan and multitask as ways to successfully balance multiple demanding roles:

It's difficult for a lot of mothers to take time away from their own children for their student-athletes. Multitasking is an absolute necessity for someone who is a mother and head AT. Knowing where to put your time and energy is hard to balance sometimes but I make it work.

The concepts of planning ahead and developing a routine were also emerging aspects of the planning theme. Many of our participants were aware of their family's needs and, in order to meet those needs as well as their work responsibilities, planned ahead for domestic tasks. For example, they made dinners or lunches in advance, arranged visits from the family, or made time to talk with their families while at work. One respondent stated, “I make dinner ahead of time for the few nights my husband might not be able to cook, and I won't be home to help.” The importance of figuring out what works best for the family was discussed by several of the participants. One, for instance, commented,

Find a regimen that works for you and your family. For example, cook dinner before you leave for work or on the weekends and then freeze it, so your husband can just reheat it. Plan a night for them to visit you at work. Plan ahead.

The need to be proactive and plan was important for our participants. Communicating the plan to their families was also important in managing the roles of mother, AT, and supervisor.

Attitude and Perspective

The attitude and perspective theme speaks to our participants' outlook on managing motherhood and athletic training in a way that was realistic, positive, and focused. This theme is best supported by one woman's observation about balancing her roles:

Motherhood and full time work is not easy, regardless of the profession. If this (athletic training) is what you want to do, do it. Don't make excuses, and don't expected [sic] to be treated differently (because you are a mother/female). Learn how to relax and enjoy your time when you are not at work by empowering and giving responsibility and ownership to your staff, without pulling out the “kid card.”

Many of our participants discussed their perspectives on their obligations and realizing that sometimes, “you get done what you get done.” This is best supported by the remarks of one participant, who said, “Something in my life will not get enough attention (just depends on if it will be athletic training or my family).” Another AT was honest in admitting, “I don't make excuses, I get the job done [at home and work]. I do my job as well as the dishes, lunches, laundry, taxi service, etc.” Another participant believed her strengths helped her balance life, sharing, “I am an extremely driven person, so I put everything I have into both my home and work life.”

Being realistic and accepting was also important in creating the sense of balance. One AT realized that it was not possible to make every sporting event or school event, but she couldn't “beat herself up about it.” So she maintained this mentality: “If I miss a soccer game, I have to look forward to the next opportunity to see her shine.” Another respondent highlighted the need for flexibility while still being fully engaged in each of her roles. She described her philosophy on celebrating special occasions throughout the year as

[r]ealizing that some celebrations may not occur on the day, but you make the time for birthdays, holidays, and when they happen make sure that you are fully committed to that occasion and not be concerned about what is going on at work.

Another aspect of the attitude and perspective theme was investing in one role at a time to successfully balance the demands of motherhood and head AT. That is, when engaging in the mother role, the focus should be on that role only and work spillover into home life should be minimized. For example, one participant noted, “When I am at work all I think about [is] work and when I am at home all I think about is home. You can not think about both at the same time and do a good job when you are [in] one location.”

Other participants had similar mindsets: “When I am home, I am present…I do not bring work home with me”; “Making family time a priority when I have ‘off' time at work”; and “I spend every minute when I am home, with my son. I tell him how much I love him, no matter how tired I am.”

Support Networks

The importance of having a support network materialized from our participants' comments (Figure 2). They recognized the need for support, both at home (personally) and from their colleagues and supervisors (professionally). One respondent said the path to success in balancing the roles of mother and head AT included “support systems.” However, these support systems do not occur in isolation; a female AT must have personal and professional support networks to simultaneously navigate motherhood and head AT duties. One participant explained, “you have to have a supportive boss/supervisor and spouse in order to balance both [roles].” Another participant advised women aspiring to balance motherhood and a leadership role to “have a good support system that includes family, friends, and students.”

Personal Support Networks

For this group of female head ATs, personal support networks included their spouses and family members. Achieving work-life balance was attributed to “I have support at home,” “having a supportive husband,” and “we have a lot of family around that helps us out!” Support was also garnered when family members understood and appreciated that athletic training is a demanding career. Regarding making it all work, one AT commented, “First and foremost having an understanding family. Without them I would not be here today.”

Having a spouse who could shoulder the load and understand the dynamics of collegiate athletics and athletic training was also part of the home support network. Being flexible and being supportive of the lifestyle were cited consistently by these ATs. For example, one said, “I married someone who respects what I do and doesn't mind the hours. We make it work.” Another woman candidly wrote, “I am fortunate to have a very supportive husband. If I did not have him I would never have been able to do my job and raise my family.” Spousal support ranged from help with day care drop-off and pickup to making time to integrate home life into the work life. As one woman observed, “We do things as a family. That might mean dinner is at 8:30.”

The importance of reciprocity in sharing the load at home was discussed by several participants. On the topic of balancing her demands, one AT said, “My support system at home is the best. My husband can take care of my daughter when I cannot be there, and I do the same for him.” Understanding by their spouses was key to succeeding as a head AT and mother: “choose a spouse that understands you and your career choice as well as goals [and] that can make all the difference.”

Professional Support Networks

The importance of support within the workplace also emerged as important to finding balance as female head ATs. This was cultivated by both the head AT herself (“I work in and foster a family oriented environment”) and by the staff (“I think I am able to manage motherhood, specifically at my current job because the staff works together to raise the children in the department”). Discussions of work-life balance centered on the development of a family-friendly, family-oriented atmosphere that was based on support and sharing family values. This was articulated by one woman who noted, “I really lucked out with the [workplace] atmosphere here. Everyone has a family and everyone is family orientated. So we all love when each other's kids come to visit.” We asked our participants for tips and advice they would share with young female ATs who may aspire to be mothers and head ATs. Several referred to finding the right workplace, one that includes support networks and people who have similar family values.

Workplace Integration

The philosophy of work-life integration challenges the traditional mindset that work and personal lives are separate and neither spills into the other. Permeable borders among work, home, and personal roles allowed our respondents to create balance. They stated that having a workplace that integrated family and work through what was viewed as a “family-orientated” atmosphere was key to their work-life balance. One participant observed, “I am not afraid to have my son join me at work. He is well behaved and welcomed, but I also do not abuse the privilege.”

Workplace integration was supported at the coworker level by several participants, who said, “My coworkers are in love with [my] daughter which makes it easy to bring her to work,” and “I work with great people, so if I have to bring my child to work, that isn't a problem. My staff loves to see my child when we come in.” A family-friendly workplace and workplace integration were also endorsed at the administrator level, as discussed by another participant regarding her success as a head AT and mother: “I am also very lucky to have an athletic director that allows me to take my kids with me or have them at games with me when time allows.” She demonstrated the importance of a supportive supervisor in order to embrace work-life integration.

Simply put, workplace integration worked because the head AT's support systems (both personal and professional) agreed that work-life balance was beneficial. This was summarized by one woman's comments: “My boys loved coming to practice when they were young, and I developed a support system by hiring responsible college students as nannies who became a part of our family.”

DISCUSSION

Assuming a leadership role in any field can be stressful and demanding, which can create challenges in achieving work-life balance. Athletic trainers serving in leadership roles, such as head AT, can struggle to find a balance as they need to juggle and manage responsibilities that can require time that extends beyond normal work hours.27 Regardless of their role in the collegiate setting, ATs experience challenges with work-life balance, which can affect career planning.15 Career advancement in athletic training has been linked to parenting.15 In fact, motherhood has been documented as a primary barrier to women assuming leadership positions, particularly the head AT role, in collegiate athletics.16 The challenges of managing the time needed to fulfill both roles seemed to concern the female AT because the leadership position required even more time than was already necessary to succeed as a staff AT. The Division I environment has often been synonymous with an intense work setting that demands time, energy, and resources and limits an individual's ability to pursue outside activities.15,28 Thus, the non–Division I environment has been discussed as a possibly more favorable workplace because of a mentality that is less “win at all costs” and more balanced between academic and athletic success. Acosta and Carpenter19 reported that more women assumed the head AT role in the non–Division I setting; because motherhood appears to keep women from assuming the head AT role in the Division I setting, we sought to understand why more mothers work outside Division I.

Inhibitors of Work-Life Balance

Head ATs are prone to experiences of role overload, which leads to conflict between personal and professional demands.29 So, comparable with the findings of Mazerolle et al,16 we too found that work-life conflict exists in the non–Division I setting. Our results, like those of previous researchers,20 suggest that collegiate level is not a major factor in work-life conflict. Organizational challenges did exist for our working mothers and were cited as barriers to finding balance, particularly the long hours worked and a limited number of days off. For others working in the collegiate setting,20 work-life conflict arises because of the expectation and need for ATs to be present and provide medical coverage. Time of year has emerged of late as another confounding element to the work-life interface for the collegiate AT20,30 and was also problematic for our female ATs. Although the summer months have traditionally been viewed as an opportunity for personal rejuvenation and time away from the athletic training room, recent changes to summer conditioning and practice rules have affected the AT's work-life balance.31 These changes occurred within the Division I setting, but the majority of our participants were contracted for 11 months, which can negatively influence work-life balance in a way that is similar.

Limited time is often the major antecedent to conflict, especially for those individuals working in collegiate athletics,3,32,33 a demanding and often inflexible subculture that requires face time. As suggested by Dixon and Bruening,3,4 conflict manifests because of an interaction of individual, sociocultural, and organizational factors. Therefore, despite documentation of organizational factors as stimuli for conflict, other factors can coexist. Sex differences have become less central within the work-life interface, yet women still tend to report more challenges with balancing multiple roles.11,15 In fact, work and life challenges have been cited as major inhibitors for women assuming leadership roles in athletic training.16 Our findings appear to show that individual (eg, motherhood), sociocultural (eg, feelings of guilt associated with motherhood), and organizational (eg, work demands, nature of the job) factors precipitate work-life conflict for women in leadership roles, lending credence to the Dixon and Bruening4 model illustrating the complexity of the work-life interface. Henderson34 described the “superwoman syndrome” in which external (eg, societal) pressures and self-imposed expectations and values plague the working woman. The idea is that working mothers in leadership roles must be able to “do it all,” successfully meeting their roles in each aspect of their lives. The working mother's dilemma then manifests, as she never feels as if she can do everything well.35

In athletic training, little attention has been given to the traditional sex ideologies of women as caretakers and men as breadwinners. A recent investigation by Mazerolle and Eason36 presented a mindset shared by our participants, which suggested that women do place more emphasis on family and the role of caretaker, a dogma that creates the platform for conflict. Because of prevailing societal gender norms, women characteristically have a harder time managing both work and family responsibilities, and they report constantly feeling as if they must prove their worth.37 Women who work and have children, regardless of marital status, often experience feelings of guilt, self-doubt, and degradation because they feel aberrant.38–40 Social norms not only make women feel that they have to choose work or family but also impart a negative social connotation in choosing work over family. A few of the women shared feelings of guilt when they needed to spend time away from their families or miss their children's activities because of work-related obligations. These feelings suggest that sex ideologies can play a role in the work-life interface, and as found by Mazerolle and Eason,36 ATs who are mothers (or intend to be mothers someday) want positions that afford them the flexibility to successfully balance both roles. In the end, the working mother must find an atmosphere that allows her to feel less guilt and provides the time to be successful as both a mother and an AT.35

Facilitators of Work-Life Balance

Our participants shared that planning was an integral part of their ability to find work-life balance and manage their expectations as working mothers. Lists, prioritization, and multitasking were time-management practices suggested by working mothers to create sanity and balance. These tactics are not isolated to working mothers but did appear to be necessary tools to permit balance for our participants.41 Several researchers42,43 in the area of work-life balance encouraged women to identify what was most important to them, personally and professionally, and then to budget time and energy for those roles accordingly. Athletic trainers reported using time-management strategies such as prioritization as a way to find work-life balance. Winterstein et al44 suggested that ATs use to-do lists to balance personal and professional obligations and ensure time for all activities. Therefore, our findings, although unique, highlight the need to be organized and efficient with use of time.

To fulfill the desire to care for their families while balancing the expectations to provide medical coverage at work, our participants planned ahead. Discussions about making meals ahead of time, having a routine, and being creative with schedules highlighted our working mothers' attempts to continue to be caretakers while also being breadwinners. These tactics speak to the importance of multitasking, being proactive, and thinking ahead, the same practices recommended to help female leaders and supervisors succeed in creating balance.45 Hakim46 suggested this mentality favors an adaptive lifestyle, which allows a woman to engage both at home and for paid work without having to invest more in one role than another. Women who persist in athletic training, particularly in the collegiate setting, appear to meet the criteria outlined by Hakim regarding lifestyle preferences, as they want to engage equally in home life and paid work.36

Our respondents were very aware that they needed personal and professional support networks in place to balance their roles as working mothers. Although these findings are not surprising, as prior authors27,47 have linked the need for support networks and achieving work-life balance, they illustrate that women in leadership roles can find balance. Working mothers who are successful in finding a balance do so because they have intentionally developed an effective support network that consists of friends, family, and coworkers.48,49 This allows for a teamwork approach, sharing the load in balancing domestic, household, and organizational responsibilities that individually can be stressful but in combination can become overwhelming. Intentional planning and support can lead to a more manageable outlook on life.49

Head ATs need to not only create their own work-life balance but also to model it. Our participants, like those studied by Mazerolle et al29 and Goodman et al,27 wanted to cultivate a workplace that allowed their staff members to find work-life balance and, thus, also allowed them to attain work-life balance. As observed by Winterstein et al,44 a shared value system among peers and supervisors is important in achieving work-life balance in athletic training. Finding a workplace that fits the family-friendly or family-oriented model has been described as important for ATs because it not only allows for job sharing and teamwork in the workplace but can, in addition, encourage the individual to capitalize on the benefits of job sharing. The professional support networks described by our participants mimic those noted by other researchers29,30 and demonstrate the connection with workplace integration. A supportive, collegial workplace can facilitate integration; those providing support agree that it works. Kossek et al50 characterized this as a workplace climate that informally supports work-life initiatives through culture.

Our working mothers discussed the importance of using workplace integration as a means to promote more time for both roles. This was also reported by head ATs working in the Division I setting.29 So workplace integration may be a strategy that benefits not only working mothers but all collegiate ATs in demanding roles, such as those of head ATs. As previously mentioned, time is a limiting factor, but workplace integration enables the working mother to make time for her role as AT and leader as well as that of mom and caretaker. Perhaps the mindset in the non–Division I setting helps to facilitate this integration, as the demands appear to be (or are perceived to be) less because of a more relaxed and balanced approach to athletics. Workplace culture, which reflects having people who share similar values working together, can lead to a better balance and mindset for the AT.48

A distinctive finding of our study was the outlook of our participants. That is, they had positive and realistic perspectives on motherhood and athletic training. Gina Rivera, cofounder of the beauty franchise Phenix Salon Suites, shared her personal philosophy: “I give the same level of respect and attention to my personal and professional life.”51 Her standards for parenting and leading focus on demonstrating that both roles are equally important, yet they require realistic expectations. Personality traits have gained attention in the evaluation of work-life balance; an individual who demonstrates emotional stability and a more positive affect is likely to cope better and navigate stressful situations with ease.52,53 Moreover, extraversion, a trait that is high in sociability and support networks, is a mediating personality trait for work-life conflict.54 Our mothers used support networks as a means to balance it all, thus providing another link to the idea that personality can mediate conflict. Although we cannot speak to this idea directly, it is likely that our participants possessed attributes commonly associated with lower levels of perceived conflict.

Limitations and Future Directions

The findings presented were collected using an online medium, which, despite its documented advantages and ability to produce rich data, is limited by a void of participant-researcher interaction. We were unable to follow up with our participants regarding their thoughts and experiences as working mothers and collegiate head ATs. We took steps to reduce the effect of this limitation but recognize that future investigators should include in-depth personal interviews or other means of data collection to triangulate our findings. We focused solely on the construct of work-life balance, and although this is a major contributor to retention in athletic training, other factors also mediate a woman's career planning. Future inquiries need to evaluate all aspects, such as other organizational and individual factors that drive career planning.

Our findings address only the women's perspective on work-life balance and juggling life, parenthood, and the role of head AT. We believe this is an important topic for the profession, as women face significant pressures to balance it all and invest time and resources simultaneously in both their work and life roles.41 Concerns for work-life balance are not isolated to female ATs; however, in athletic training, achieving this balance appears to be more concerning for them, especially when motherhood is introduced. Future authors should gather the perspectives of fathers as they navigate working in the collegiate setting and in roles outside this workplace. This is particularly important because the generally accepted notion of fatherhood and success founded on breadwinning is changing as fathers become perceived as having more diverse roles and not being solely responsible for the financial needs of families.

CONCLUSIONS

Our participants, like many ATs, experienced conflicts among their roles as mothers, ATs, and leaders. Our findings support the conceptual model developed by Dixon and Bruening,3 which suggests that conflict occurs not because of one factor but rather because of a combination of competing expectations and roles at multiple levels. Organizationally, our participants juggled long work hours, travel, and administrative tasks. Individually and socioculturally, they had to overcome their guilt and their need to be present and an active part of the parenting process.

These mothers demonstrated the ability to cope with their demanding roles as mothers and head ATs. They did so by planning, being adaptable, using support when necessary, and taking the time to integrate roles instead of keeping them segregated. Perhaps motherhood made them better at both roles, as they gained the positive attributes from each role, a fundamental component of a work-life–enrichment perspective. Mentorship, and specifically the lack of women mentors, has been discussed as a barrier to the head AT role.15 We hope our findings highlight the fact that women can succeed in this leadership role while raising a family.

We encourage female ATs to develop routines to assist with day-to-day responsibilities (eg, cooking, meal planning, game coverage). Having a realistic yet positive attitude can reduce stress and improve their job outlook. Female ATs should try to embrace each role and value what it brings into their life while engaged in that role (eg, while at a child's soccer game, turn off the phone, or while providing patient care, focus on the task at hand). Finally, delegating tasks and asking for assistance can be useful tools to help mothers and leaders successfully navigate work-life balance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Rhyan Lazer, MS, ATC, for her insights into the data and presentation of the results.

Appendix. Structured Interview Guidea

How would you describe your work life balance?

What factors impact your work life balance working in your current practice setting?

What challenges do you face as a working mother?

How have you managed working full-time and being a mother?

What factors have allowed you to persist in your current position?

What advice would you share with a young female athletic trainer, aspiring to become a head athletic trainer?

How have your current, past, or future family intentions (ie, intentions to get married or have children) been influenced by your career?

What about your current employment setting is favorable?

Why did you choose to work in this practice setting?

How do you describe your parenting philosophy?

-

Does this impact your ability to find a balance between work life and home life?

a The interview guide is reproduced in its original form.

REFERENCES

- 1. Parker K. Despite progress, women still bear heavier load than men in balancing work and family. Pew Research Center Web site. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/03/10/women-still-bear-heavier-load-than-men-balancing-work-family/. Accessed June 7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Williams JC, Boushey H. The three faces of work-family conflict: the poor, the professionals, and the missing middle. Center for American Progress Web site. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/labor/report/2010/01/25/7194/the-three-faces-of-work-family-conflict/. Accessed June 7, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Perspectives on work-family conflict in sport: an integrated approach. Sport Manage Rev. 2005; 8 3: 227– 253. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dixon MA, Bruening JE. Work-family conflict in coaching, I: a top-down perspective. J Sport Manage. 2007; 21 3: 377– 406. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goldberg WA, Tan ET, Thorsen KL. Trends in academic attention to fathers, 1930–2006. Fathering. 2009; 7 2: 159– 179. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bianchi SM, Robinson JP, Milkie MA. Changing Rhythms of American Family Life. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Williams A, Franche RL, Ibrahim S, Mustard C, Layton FR. Examining the relationship between work-family spillover and sleep quality. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006; 11 1: 27– 37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ, Burton LJ. Work-family conflict, part II: job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008; 43 5: 513– 522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mazerolle SM, Goodman A, Pitney WA. Factors influencing retention of male athletic trainers in the NCAA division I setting. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2013; 18 5: 6– 9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goodman A, Mensch JM, Jay M, French KE, Mitchell MF, Fritz SL. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010; 45 3: 287– 298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Naugle KE, Behar-Horenstein LS, Dodd VJ, Tillman MD, Borsa PA. Perceptions of wellness and burnout among certified athletic trainers: sex differences. J Athl Train. 2013; 48 3: 424– 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kahanov L, Eberman LE, Juzeszyn L. Factors that contribute to failed retention in former athletic trainers. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2013; 11 4: 1– 7. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Graham JA, Dixon MA. Coaching fathers in conflict: a review of the tensions surrounding the work-family interface. J Sport Manage. 2014; 28 4: 447– 456. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bruening JE, Dixon MA. Work-family conflict in coaching, II: managing role conflict. J Sport Manage. 2007; 21 4: 471– 496. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Ferraro EM, Goodman A. Career and family aspirations of female athletic trainers employed in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 2: 170– 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mazerolle SM, Burton LJ, Cotrufo RJ. The experiences of female athletic trainers in the role of the head athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 1: 71– 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schenewark JD, Dixon MA. A dual model of work-family conflict and enrichment in collegiate coaches. J Issues Intercoll Athl. 2012; 5: 15– 39. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carlson DS, Kacmar KM, Wayne JH, Grzywacz JG. Measuring the positive side of the work-family interface: development and validation of a work-family enrichment scale. J Vocat Behav. 2006; 68 1: 131– 164. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Acosta RV, Carpenter LJ. Women in intercollegiate sport: a longitudinal, national study. Thirty-seven year update. 1977–2014. www.acostacarpenter.org. Accessed June 8, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Eason CM. Experiences of work-life conflict for the athletic trainer employed outside the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I clinical setting. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 7: 748– 759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Caelli K. Engaging with phenomenology: is it more of a challenge than it needs to be? Qual Health Res. 2001; 11 2: 273– 281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Finlay L. Debating phenomenological research methods. Phenomenology Pract. 2009; 3 1: 6– 25. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Englander M. The interview: data collection in descriptive phenomenological human scientific research. J Phenomenologic Psychol. 2012; 43: 13– 35. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Colaizzi P. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. : Valale R, King M. Existential-Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1978: 48– 71. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fischer CT. Bracketing in qualitative research: conceptual and practical matters. Psychother Res. 2009; 19 4–5: 583– 590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meho LI. E-mail interviewing in qualitative research: a methodological discussion. J Am Soc Inf Sci Technol. 2006; 57 10: 1284– 1295. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goodman A, Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA. Achieving work-life balance in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting, part II: perspectives from head athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 1: 89– 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mazerolle SM, Ferraro EM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Factors and strategies contributing to the work-life balance of female athletic trainers employed in the NCAA Division I setting. Athl Train Sport Health Care. 2013; 5 5: 211– 222. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mazerolle SM, Goodman A, Pitney WA. Achieving work-life balance in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting, part I: the role of the head athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 1: 82– 88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Trisdale W. Work-life balance perspectives of male NCAA Division I athletic trainers: strategies and antecedents. Athl Train Sport Health Care. 2015; 7 2: 50– 62. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mazerolle SM, Eason CM, Goodman A. Exploring summer medical care within the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting: a perspective from the athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2016; 51 2: 175– 183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dixon MA, Sagas M. The relationship between organizational support, work-family conflict, and the job-life satisfaction of university coaches. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2007; 78 3: 236– 247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mazerolle SM, Bruening JE, Casa DJ. Work-family conflict, part I: antecedents of work-family conflict in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008; 43 5: 505– 512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Henderson R. Time for a sea change. : Allen I. Balance: Real-Life Strategies for Work/Life Balance. Kingscliff, NSW, Australia: Sea Change Publishing; 2006: 9– 19. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Storms S. Motherhood Is the New MBA: Using Your Parenting Skills to Be a Better Boss. New York, NY: Thomas Dunne Books; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mazerolle SM, Eason CM. Perceptions of National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I female athletic trainers on motherhood and work-life balance: individual- and sociocultural-level factors. J Athl Train. 2015; 50 8: 854– 861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pastore DL, Inglis S, Danylchuk KE. Retention factors in coaching and athletic management: differences by gender, position, and geographic location. J Sport Soc Issues. 1996; 20 4: 427– 441. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garey AI. Weaving Work and Motherhood. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Birrell SJ. Discourses on the gender/sport relationship: from women in sport to gender relations. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1988; 16: 459– 502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gutek BA, Searle S, Klepa L. Rational versus gender role expectations for work-family conflict. J Appl Psychol. 1991; 76 4: 560– 568. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heath K. Women in Leadership: Strategies for Work-Life Balance [dissertation]. Malibu, CA: Pepperdine University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sachs W. How She Really Does It: Secrets of Successful Stay-at-Work Moms. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Goodchild S. Are you happy in all the roles you play in life? : Allen I. Balance: Real-Life Strategies for Work/Life Balance. Kingscliff, NSW, Australia: Sea Change Publishing; 2006: 63– 74. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Winterstein AP, Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA. Workplace environment: strategies to promote and enhance the quality of life of an athletic trainer. Athl Train Sports Health Care. 2011; 3 2: 59– 62. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lerner S. The War on Moms: On Life in a Family-Unfriendly Nation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hakim C. Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century: Preference Theory. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mazerolle SM, Pitney WA, Goodman A, Eason CM. National Athletic Trainer's Association position statement: work-life balance recommendations. J Athl Train. 2016. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gallagher C, Golant SK. Going to the Top: A Road Map for Success From America's Leading Women Executives. New York, NY: Viking Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hattery A. Women, Work, and Family: Balancing and Weaving. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kossek EE, Lewis S, Hammer LB. Work–life initiatives and organizational change: overcoming mixed messages to move from the margin to the mainstream. Hum Relat. 2010; 63 1: 3– 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fallon N. Female leaders on how to achieve work-life balance. Business News Daily Web site. www.businessnewsdaily.com/6342-female-leader-work-life-balance.html. Accessed June 8, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995; 69 5: 890– 902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McCrae RR, John OP. An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. J Pers. 1992; 60 2: 175– 215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. DeNeve KM, Cooper H. The happy personality: a meta analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. 1998; 124 2: 197– 229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]