Abstract

Somatic stem cells replenish many tissues throughout life to repair damage and to maintain tissue homeostasis. Stem cell function is frequently described as following a hierarchical model in which a single master cell undergoes self-renewal and differentiation into multiple cell types and is responsible for most regenerative activity. However, recent data from studies on blood, skin and intestinal epithelium all point to the concomitant action of multiple types of stem cells with distinct everyday roles. Under stress conditions such as acute injury, the surprising developmental flexibility of these stem cells enables them to adapt to diverse roles and to acquire different regeneration capabilities. This paradigm shift raises many new questions about the developmental origins, inter-relationships and molecular regulation of these multiple stem cell types.

In the late 1800s, descriptive pathology portrayed the cellular structure of many organs in exquisite detail. In the absence of modern experimental tools such as fluorescence imaging, tissue transplantation and animal models, developmental relationships among cell types were inferred from extensive observation of the tissues of interest and documented by detailed hand drawings. Observations of the bone marrow led to heated debate about whether the distinct lymphoid and myeloid components of the blood were continuously generated from a common cell or from distinct progenitor cells (a view championed by Paul Ehrlich). The term ‘stem cell’ (Stammzelle) first appeared in the literature around 1900, when it was used by Artur Pappenheim and others to promote the common progenitor concept1 (reviewed in REF. 2). For the past century, this concept has been the foundation of our understanding of tissue regeneration.

In the mid-1950s, bone marrow transplantation in mice, combined with tracking of the cellular progeny of transplanted tissue on the basis of the presence of common chromosomal translocations, strongly supported the hypothesis that cells of both lymphoid and myeloid lineages originate from the same cell3. Corroboration of this idea came from studies in which transplanted cells were marked by retroviral transduction; integration sites that were shared by multiple blood lineages were considered to be indicative of a common originating cell4,5. Thus, for more than 50 years, the research field has accepted the view that the haemato poietic system is maintained by a single type of stem cell that regenerates all of the blood lineages during adulthood.

Concepts of tissue regeneration that were developed from the study of haematopoiesis have provided a framework for understanding the mechanisms that underlie the maintenance of other tissues. As transplantation was not easily practicable in other tissues such as the skin and the intestine, the stem cell paradigm in these tissues gained support through experiments in which cell fates were followed using tritiated thymidine labelling6. Data from these experiments reinforced a model in which a single tissue-specific stem cell continuously regenerates some or all of the lineages in a given tissue.

Somatic stem cells have thus come to be defined as adult-derived cells that have two hallmark capabilities: the ability to undergo differentiation and generate multiple lineages over long periods of time; and the ability to simultaneously self-renew (that is, to regenerate themselves). Traditionally, the stem cell pool within a single tissue was thought to be uniform: all stem cells in the pool were presumed to have equivalent potential for differentiation and self-renewal.

However, recent data that were generated using new technologies in various systems (BOX 1) have indicated that, in many somatic tissues, the stem cell system is surprisingly heterogeneous, comprising different types of stem cells. Here, we review the evidence in support of such heterogeneity and present instructive examples from haematopoietic, skin and intestinal epithelium that argue in favour of a profound revision of traditional views. Stem cell systems in other tissues, including stomach, mammary gland and prostate tissues, which are not discussed in this Review, may also be worth reconsidering in light of this evidence7–9. Similarly, malignancies may represent a special case of stem cell heterogeneity that fits into this broad conceptual framework (BOX 2).

Box 1. Strategies used to investigate heterogeneity.

Different strategies can be used to examine stem cell function and heterogeneity in different tissue systems. For example, in the case of bone marrow haematopoietic stem cells, the stem cells are often extracted from their niche and examined using functional assays such as transplantation. By contrast, transplantation is difficult to perform in the intestine; however, lineage tracing has been a powerful technique that has been used to identify and characterize the progeny of cells that are located in specific anatomical locations. Mouse hair follicle stem cells can be expanded in vitro and transplanted, and can generate hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Not all experimental strategies for studying stem cells are applicable to all tissues, and they could be better exploited in some cases, as detailed in the table.

Table 1.

| Experimental strategy | Achieved in blood | Achieved in skin | Achieved in the intestine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expansion of multipotent stem cells in vitro | No | Yes | Yes |

| Generation of tissue and/or stem cells from pluripotent stem cells | No | Yes | Yes, but needs work |

| Lineage tracing | No* | Yes | Yes |

| Transplantation | Yes | Yes | Yes, but inefficient |

| Single-cell analysis | Yes, but needs work | No | No |

| Barcoding of libraries of cells | Yes | No | No |

Lineage relationships have been established largely through transplantation assays rather than by labelling of cells under homeostatic conditions.

Box 2. Cancer stem cell heterogeneity.

The concept of ‘cancer stem cells’ emerged in the 1990s to explain there emergence of cancer many years after apparent eradication, perhaps through a long-lived stem-like cell. Considerable debate about the existence of these cells and their importance in cancers of different tissues has continued for the past 15 years. As for normal somatic stem cells, our understanding of the identity and behaviour of cancer stem cells has evolved. It is now believed that different models explain there-emergence of cancer in different tissues and even within a given type of cancer: in some cases, a traditional hierarchical stem cell model may be accurate; in others, many (and sometimes all) of the cells in the tissue can function like stem cells.

Recently, ultra-deep genome sequencing of malignancies has begun to shed light on the identity and characteristics of cancer stem cells in some tissues. In acute myeloid leukaemia (AML), a small number of mutations arise in bona fide stem cells. These mutations, in genes such as DNMT3A and genes encoding members of the cohesin family, provide a growth advantage in these stem cells, which are otherwise fairly normal. Haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) with such mutations represent a pre-leukaemic state, in which their properties are subtly altered such that further mutations have a large proliferative effect, quickly initiating leukaemia. In these cases, it is very likely that the mutations occur in an HSC123–125. Multiple secondary or tertiary mutations can occur, generating a diversity of cell clones that coexist, compete and show distinct growth dynamics following chemotherapy126. This clonal heterogeneity has enormous implications for how to ablate these kinds of malignancies, as using drugs that only target branches of the original malignant clone would almost certainly lead to a relapse. Thus, it will be crucial to develop new drugs that are designed to kill cells carrying the initiating mutation. Although this paradigm is well understood for at least some types of adult AML, other malignancies may be initiated by a progenitor127. Furthermore, the extent to which all cells in a tumour, or a subset of stem‑like cells, can initiate the growth of a secondary tumour probably varies among malignancies of different types128,129.

Evolving concepts in haematopoiesis

The haematopoietic system is one of the most dynamic systems in the body; billions of blood cells are generated every day to continuously replace the dozen or so different peripheral blood cell types that are expended (FIG. 1). Since the first bone marrow transplantation experiments in the 1950s, substantial experimental effort has been made to identify reconstituting haematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). This culminated in the establishment of several robust strategies for their purification in the 1990s, which have facilitated their study.

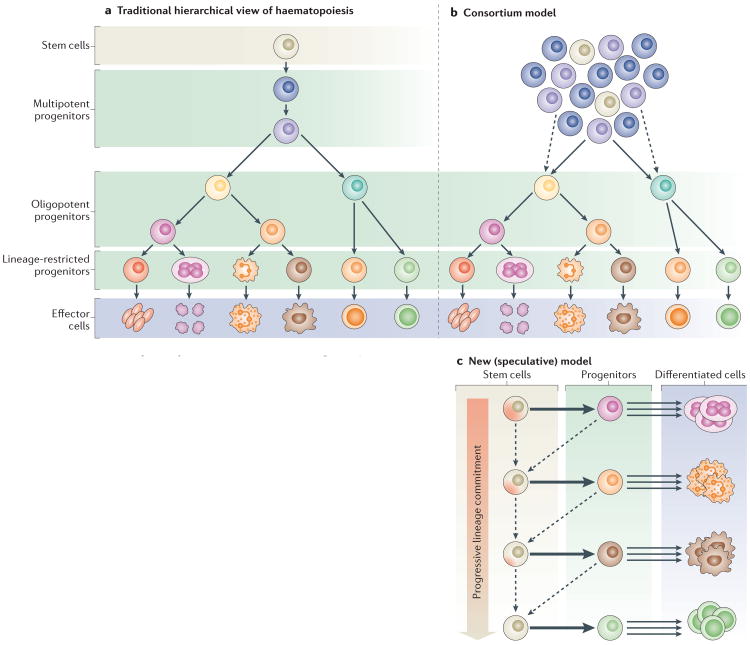

Figure 1. Stem cell models for the haematopoietic system.

a | The traditional hierarchical view of haematopoiesis is that there is one type of stem cell that has the capacity to give rise to lineage-restricted progenitors that differentiate into all the cell types of the blood with equivalent propensity. b | In the consortium model, a pool of stem cells with slightly different properties regenerates the system continuously through progenitors that are increasingly restricted in their potential. c | In a new speculative model, stem cells are rare reserve cells that occasionally generate lineage-restricted progenitors. These stem cells have different lineage biases and give rise to specific progenitors. Existing data suggest that the most primitive stem cells are primed towards the megakaryocyte lineage22. These stem cells give rise to progenitors that are largely restricted to specific fate choices, and these progenitors are the main drivers of haematopoiesis, generating massive numbers of differentiated cells over a long period of time. During extreme stress (such as major injury or transplantation), the progenitors may revert (dashed arrows pointing left) to a stem-like state while retaining some of their lineage preferences. This model is consistent with the reported existence of megakaryocyte-biased stem cells (cells at the top of the progenitor hierarchy) and lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors (one-step-down stem-like cells that lack megakaryocyte differentiation potential) as well as with the increasing differentiation bias observed with age. Indeed, it has been shown that the progenitors lose their developmental flexibility during ageing. Models that are hybrids of the three that are outlined in this figure can also be envisioned.

Variations in HSC behaviour

HSCs are widely viewed as being a uniform population of cells with an equivalent capacity to generate diverse progeny. Nevertheless, data have for some time suggested that there is considerable variation among individual stem cells. For example, single purified HSCs showed large fluctuations in their contribution to myeloid and lymphoid lineages when engrafted in recipient mice, suggesting that there is inherent variability in self-renewal and multilineage differentiation despite the cell population that was used for transplantation being highly purified10. Similarly, transplants of clonally derived HSCs from in vitro cultures displayed marked variation in repopulation kinetics among the transplanted cells as well as differences in their myeloid-to-lymphoid cell output ratio11. Importantly, serial transplantation of bone marrow derived from the clones showed that daughter and granddaughter HSCs recapitulated the behaviour of their parent clone. These studies all indicated that the self-renewal and differentiation capacity of individual HSCs was both varied and intrinsically predetermined. Subsequent work led to the hypothesis that there are two classes of HSC: myeloid-biased HSCs (which preferentially give rise to myeloid progeny), and lymphoid-biased HSCs (which produce proportionately more lymphoid than myeloid cells)12.

Although intriguing, this hypothesis only took root following a landmark study of a large cohort of mice that had been transplanted with single purified HSCs. The differentiation of individual HSCs was followed for many months, in primary and secondary transplant recipients, offering an unprecedented view of the diversity of the adult mouse HSC pool13. Two main classes of cell with multilineage HSC-like activity, which were designated α-cells and β-cells, were considered to be bona fide HSCs with the ability to sustain all blood production in the long term. α-cells displayed reduced capacity for generating lymphoid lineages (similar to myeloid-biased HSCs), and β-cells showed diminished production of myeloid progeny (that is, they were lymphoid biased). These behaviours were remarkably durable. After transplantation into secondary recipients, these differentiation-biased behaviours were recapitulated, and the HSCs that were regenerated were primarily of the same type as the original transplanted cell, supporting the idea that cell behaviours are largely predetermined in nature (although some interconvertibility was also reported). Although it remains unclear when this heterogeneity arises, it is already apparent in HSCs that have been purified from mouse fetal tissue14, suggesting that HSC subtypes are established during embryogenesis or shortly after. A meta-analysis of marking studies in the human bone marrow indicated that human HSCs also have heterogeneous regenerative properties15.

These studies led to the view that HSCs exist as two distinct stem cell types, but in fact they show a range of intermediate behaviours (FIG. 1). Thus, purification of individual HSC types has been challenging, which has impeded both their strict classification and their study at the molecular level. Nevertheless, some strategies have emerged to partially separate HSCs with discrete properties. For example, the fluorescent DNA-binding dye Hoechst 33342, which is pumped out of HSCs, can be used to distinguish a range of HSCs that are otherwise similar with regard to cell surface markers. When tested by single-cell transplantation, HSCs with the greatest dye efflux showed enhanced production of myeloid progeny, whereas HSCs with the least dye efflux favoured lymphoid cell generation. Moreover, lymphoid-biased HSCs displayed lower overall reconstitution and produced progeny for a shorter period of time than the myeloid-biased HSCs16.

Other markers that have been used to partially distinguish between HSC subtypes include Cd150 (REFS 16–19) and other signalling lymphocytic activation molecule (SLAM) family surface markers130, integrin α2 (REF. 20), Cd41 (also known as Itga2b)21 and von Willebrand factor homologue (Vwf)22. In addition, HSC classes have been reported to differ in their sensitivity to transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) signalling16,23 and in their response to gamma irradiation24. Importantly, the more myeloid-biased HSCs show the greatest level of quiescence, whereas the more lymphoid-biased HSCs divide more actively16,17,130. This difference in proliferative behaviour alone could account for many measurable differences in the HSCs, such as the more limited time frame during which they can contribute after transplantation (reviewed in more detail in REF. 25). Together, these and other studies have contributed to changing our view of stem cells from being a single cell type to a consortium of cell types (FIG. 1), all of which contribute to blood regeneration.

Intrinsic and extrinsic regulation

An important question that has arisen from these findings is whether intrinsic and/or extrinsic cues regulate and confer these different HSC behaviours. Differences in growth factor responsiveness are indicative of intrinsic regulation16,23. However, technologies that facilitate analyses at the single-cell level by microarrays26, real-time PCR27,28, RNA sequencing29,30 and epigenetic analysis30,31 should ultimately yield new insights into the molecular mechanisms that underlie HSC heterogeneity. For example, DNA methyltransferases are differentially expressed among HSC types in mice32.

A particular challenge for understanding the molecular regulation of HSCs results from the fact that HSC types are probably a continuum of states, which are characterized by subtle differences such as small changes in gene expression (on the order of twofold–threefold, as reported in REF. 16), the functional significance of which may be difficult to discern.

Currently, little is known about extrinsic regulation of HSC types. However, we speculate that different HSC types may be associated with distinct niches that influence the differentiation and self-renewal capacity of these cells. In recent years, several cell types have been identified as potential niche constituents, including osteoblasts33, endothelial cells34,35, Schwann cells36 and megakaryocytes37 (reviewed in REF. 38). Most of these are candidates for physical association with different HSC subtypes, which may direct different differentiation patterns.

How do HSCs normally behave?

Transplantation experiments have shown that HSCs have a range of properties, which raises the question of how they naturally behave, in the absence of such perturbations. Despite advances in technologies, such as transplantation of single HSCs and barcoding, that enable the investigation of cellular behaviours with unprecedented detail, HSCs are still largely defined by their functional output in assays that broadly mimic extreme circumstances, such as recovery from injury. The stem cell activities that are observed in these assays are unlikely to reflect in vivo behaviours under normal homeostasis, and they may not occur even during typical injury recovery. For example, single-cell transplantation is considered to be the ultimate test to define the differentiation competence of a cell. However, a single cell is unlikely to ever need to regenerate an entire tissue. Thus, this extreme test may push a cell to behave in ways it would not typically behave.

To determine normal cellular dynamics and differentiation capacity, it is necessary to use strategies that mark and track cells with minimal perturbation of endogenous tissues. In vivo transposon tagging was the first approach of this kind and has now been used to track blood cell production in mice without cell transplantation39. When transposition was stimulated, and transposon insertion sites were tracked in multiple blood lineages over time, tags that were common to multiple lineages were rarely observed. Instead, the majority of neutrophils (which are the blood cells with the highest turnover) were continuously generated from very long‑lived lineage‑restricted progenitors39. These progenitor cells produced neutrophils for more than 1 year, a time frame in which only HSCs were thought to operate. These data could indicate the existence of stem-like cells that give rise exclusively to neutrophils or the existence of neutrophil-restricted progenitors with extraordinary longevity. These recent observations are not incompatible with the traditional HSC concept, but they do call into question the circumstances in which true multipotent cells or lineage restricted progenitors are used. Much more work remains to be done to understand these cellular dynamics.

A new model of haematopoiesis

Together, these recent studies challenge the traditional hierarchical view of HSC differentiation, in which a relatively uniform pool of HSCs regenerates all peripheral blood cells with equal propensity over a long period of time (FIG. 1a). However, even in traditional transplantation assays, HSCs have been shown to be predestined to produce one lineage in preference to others, with some HSCs potently contributing to single lineages, such as neutrophils and megakaryocytes, over long periods of time22,39,40. These data suggested a consortium model of stem cells with slightly varied differentiation propensities (FIG. 1b). In this model, all of the HSCs could be used for blood production, generating all cell types in the differentiated progeny, with variations in their output (that is, bias towards myeloid or lymphoid differentiation). This view could be reconciled with the most recent data and lead to a new model (FIG. 1c), which would bring together many disparate observations.

One possibility is that stem-like cells are established early during development (perhaps different stem cells are associated with different niches). These stem-like cells mainly generate long-lived progenitors that then almost exclusively produce one or a few lineages of cells. Some of these dedicated progenitors may retain a degree of developmental flexibility, such that they can revert to a more primitive state under conditions of duress (for example, transplantation), in which they behave more like stem cells. Dedicated progenitors that revert to oligopotency (that is, stem-like progenitors) may differ in their differentiation capacity, which may correspond to behaviours that have been interpreted as HSC differentiation bias. The lineage relationship between these stem-like progenitors may be one of stepwise loss of differentiation potential (FIG. 1c), which would be consistent with the existence of cells such as the lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor41 that lack only megakaryocyte–erythroid potential.

New experimental approaches are required for rigorous testing of this model of haematopoiesis. Nonetheless, the recent data on HSC potential should prompt a re-evaluation of the definitions of stem cells.

Skin epithelial stem cells

Similar to bone marrow cells, a large number of skin cells are continuously regenerated throughout life. The regenerative potentials of epidermal progenitors have been studied for decades and form a foundation for both experimental and therapeutic stem cell biology. The skin is an easily accessible tissue, which has enabled the three-dimensional landscape of its cell types and their interactions to be mapped in great detail.

The skin epithelium comprises the interfollicular epidermis (IFE) and its appendages, which include hair follicles, sebaceous glands and sweat glands42. During early development, a single layer of ectodermal cells gives rise to the entire IFE and its appendages. After morphogenesis, the hair follicle goes through cyclical phases of regression, rest and growth43. During the resting phase of the hair cycle, the permanent part of the hair follicle is divided into several compartments, which are anatomically and biochemically distinct (FIG. 2). These include the infundibulum, which is contiguous with the IFE in the uppermost portion of the hair follicle; the isthmus, which is located directly below the infundibulum and above the hair follicle bulge; and the hair germ, which is situated directly below the bulge and on top of the dermal papilla, which is a cluster of specialized mesenchymal cells that are required for hair follicle regeneration44,45.

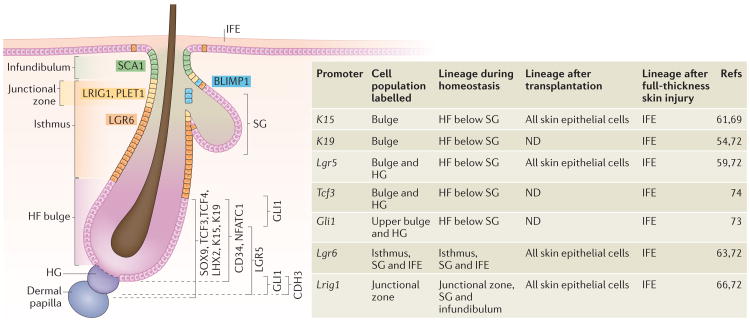

Figure 2. Heterogeneity of skin epithelial stem cells.

The resting-phase hair follice(HF) contains several compartments (indicated by different colours), which are defined by cells that express distinct molecular markers: stem cell antigen 1 (Sca1; also known as Ly6a), leucine-rich repeats and immunoglobulin-like domains 1 (Lrig1), placenta-expressed transcript 1 (Plet1), leucine-rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptor 6 (Lgr6), Blimp1, Sox9, transcription factor 3 (Tcf3), Tcf4, LIM homeobox 2 (Lhx2), keratin 15 (K15), K19, CD34, nuclear factor of activated T cells, cytoplasmic calcineurin-dependent 1 (Nfatc1) and Gli1. The compartments above the HF bulge include the infundibulum, which is contiguous with the interfollicular epidermis (IFE) in the uppermost portion of the HF; the isthmus, which is located directly below the infundibulum; and the junctional zone, which is part of the upper isthmus and lies next to the sebaceous gland (SG). These compartments contain their own stem cells that maintain their homeostasis. The bulge itself contains HF stem cells, whereas the hair germ (HG), which is located directly below the bulge, comprises progenitor cells. The HG is marked by high levels of cadherin 3 (Cdh3) expression and is situated on top of the dermal papilla, which is a cluster of specialized mesenchymal cells that are required for HF regeneration. HFs comprise a heterogeneous population of stem cells, which express different markers as indicated. As listed in the table, lineage tracing using inducible Cre recombinases under the control of specific promoters, which are expressed in distinct cell populations, shows the restricted lineage potential of the heterogeneous populations during normal homeostasis as well as an expanded potential in response to injury. ND, not done.

Multiple epidermal populations with stem cell activity in vitro?

The bulge region, which was first identified as the hair follicle stem cell reservoir, contains cells that have high proliferative capacity in vitro46,47 and are slow cycling in vivo, as demonstrated by their ability to retain nucleotide analogues or labelled histone in pulse-chase experiments (so‑called label‑retaining cells)47–50. In mice, such bulge cells are uniquely marked by CD34 (REF. 51) and nuclear factor of activated T cells, cytoplasmic calcineurin-dependent 1 (NFATC1) expression52, and bulge cells and the hair germ express keratin 15 (K15; also known as KRT15)53, K19 (also known as KRT19)54, transcription factor 3 (TCF3)55, TCF4 (REF. 56), LIM homeobox 2 (LHX2)57, SOX9 (REF. 58) and leucinerich repeat containing G protein-coupled receptor 5 (LGR5)59. When isolated bulge cells are combined with neonatal dermal cells in transplantation assays in immunodeficient mice, they can reconstitute all skin epithelial lineages, including the IFE, hair follicle and sebaceous gland59–62. Thus, for some time, bulge cells were thought to be the true multipotent stem cells at the apex of the epidermal hierarchy.

Subsequently, cells in the isthmus, which are marked by LGR6 (REF. 63), and cells in the junctional zone in the upper isthmus64, which are marked by leucine‑rich repeats and immunoglobulin‑like domains 1 (LRIG1) and placenta-expressed transcript 1 (PLET1)65,66, were also found to have high proliferative capacities in vitro. These cells were able to contribute to all three skin epithelial lineages in transplantation assays. These data indicated that various populations of cells with distinct markers can reconstitute all skin epithelial lineages. The field then began to question whether the stem cell potential of these heterogeneous populations was indicative of endogenous stem cell function.

Normal epidermal stem cell function

Meanwhile, evidence was accumulating that the IFE and hair follicle are maintained by separate stem cell populations under physiological conditions. Although retroviral fate mapping had previously suggested the existence of discrete stem cell compartments67, lineage tracing in which cells of the embryonic hair follicle buds were marked showed for the first time that the entire hair follicle, including the sebaceous gland, but not the IFE, was derived from these embryonic progenitor cells. This new evidence indicated that the IFE and its appendages are derived from separate pools of stem cells58,68. In addition, a cell ablation experiment that used the K15 promoter to drive the expression of an inducible ‘suicide gene’ to ablate adult bulge cells led to the complete loss of hair follicles but did not affect the IFE, indicating that a separate pool of stem cells maintains IFE homeostasis69. Finally, lineage tracing in adult tissue showed that the basal layer of the IFE contains its own stem cells, which maintain the stratified epidermis70,71.

Although embryonic progenitors in hair follicle buds contribute to all cells in the hair follicle and the sebaceous gland58,68, lineage-tracing experiments have shown that under physiological conditions discrete stem cell populations in adult tissues maintain the sebaceous gland as well as distinct components of the hair follicle (FIG. 2).

Various groups have shown, through lineage tracing using mutant mice expressing the Cre recombinase fusion proteins CrePR (which is fused to a truncated progesterone receptor) and CreER (which is fused to a truncated oestrogen receptor), that bulge and hair germ cells predominantly give rise to the lower part of the hair follicle. Specifically, these studies used bulge and hair germ-specific inducible K15–CrePR transgenic mice61, and K19–CreER54,72, Lgr5–CreER59,72, Gli1–CreER73 and Tcf3–CreER74 knock-in mice (see the activity of these promoter s in FIG. 2).

Lineage tracing has also shown that the infundibulum and the sebaceous gland are maintained by Lrig1+ cells, which are located in the junctional zone and the basal layer of the sebaceous gland72. Blimp1+ cells75, which are located adjacent to the sebaceous glands and are distinct from Lrig1+ cells72, can also give rise to sebaceous gland cells75; however, this finding has recently been disputed76. Previously, Lgr6+ cells were reported to be located in the adult central isthmus and to give rise to the sebaceous gland and IFE63. However, recent studies have shown that Lgr6+ cells are not restricted to the isthmus but are also present in the sebaceous gland and IFE72,77.

Although lineage tracing is a very powerful tool for identifying stem cell populations in the skin, it relies on cell-type- and temporal-specific induction of Cre recombinases and therefore produces slightly different results depending on the timing of the labelling74,78. Collectively however, the results that have been obtained using this approach strongly support the concept of stem cell heterogeneity in the hair follicle, in which several distinct pools of stem cells regenerate one or more parts of the hair follicle.

Not only are there heterogeneous populations of stem cells within the hair follicle, there is heterogeneity within the bulge itself. Lgr5+ cells, which are proliferative cells located in the lower part of the bulge and the hair germ, are distinct from the quiescent label-retaining cells and only partially overlap with Cd34+ and K15+ bulge cells59. In addition, two distinct subcompartments of the bulge express Gli1 (REF. 73). A recent study, using lineage tracing of single cells in combination with live imaging, revealed differences between the fates of stem cells located in the upper bulge and those located in the lower bulge, further supporting the finding that bulge cells are heterogeneous. Cells in the upper bulge tend to remain in the bulge and do not contribute to hair follicle regeneration, whereas cells in the lower bulge regenerate the outer root sheath of the hair follicle79. Cells of the hair germ, which express many of the same molecular markers as bulge cells, have their own molecular signature80 and mainly contribute to differentiated lineages of the hair follicle, but they can also contribute to the regeneration of the outer root sheath79.

Although they are heterogeneous in their molecular markers, proliferative propensity and cell fate, these discrete populations in the hair follicle can interconvert and diverge into different lineages to replace damaged cells. Elegant experiments that used laser ablation and in vivo imaging have shown that, after bulge ablation, neighbouring cells from the hair germ or upper hair follicle region repopulate the ablated area and acquire bulge cell identity, and are capable of regenerating the lower part of the hair follicle. Similarly, laser ablation of hair germ cells induces bulge cells to reconstitute the hair germ and give rise to new hair growth79. Following wounding by removal of a full‑thickness piece of skin (that is, including the dermis as well as the epidermis), the majority of the re-epithelialized portion of the IFE is derived from the neighbouring basal cells of the IFE71, although cells from discrete compartments of the hair follicle have also been found to contribute to the regeneration and repair of the IFE58,63,69,72–74,81.

The fate-determining role of the microenvironment

Stem cell niches, which support and regulate stem cell function, contain numerous cell types, although the precise cellular constitution is unique to each niche. In the skin, the dermal papilla is required for hair follicle stem cell activation44. In addition, adipocytes, nerves and the arrector pili muscle have all been shown to affect either the characteristics or the behaviour of the hair follicle stem cells73,77,82,83, and thus they are all candidate components of the hair follicle stem cell niche. Niche cells can be descendants of stem cells: for example, K6+ inner bulge cells (which are descendants of the bulge cells and function as a niche for bulge cells) secrete factors that promote hair follicle stem cell quiescence78.

As discussed above, lineage-tracing experiments indicate that, under physiological conditions, hetero-geneous populations of stem cells are restricted in their lineage differentiation potential. However, transplantation experiments, in which cells are removed from their natural environments, clearly show that these cells have the capacity to give rise to all skin epithelial lineages. These observations suggest that the intrinsic fate of these cells is not irreversibly predetermined and that the microenvironment in which the heterogeneous populations reside restricts their lineage choice.

Different microenvironments probably influence the behaviour of stem cells by conferring on them differential proliferative properties and dictating the expression of their molecular markers. Recent studies in which denervation abolished the specific expression pattern of the stem cell markers Gli1 (REF. 73) and Lgr6 (REF. 77) in the hair follicle underscored the importance of this interaction between the microenvironment and the stem cell population. The role of the microenvironment in influencing stem cell fate has also been shown for melanocyte stem cells, which are another stem cell population in the hair follicle36,84,85.

Further work will be required to identify the signals from the microenvironment that specify the identity of heterogeneous stem cell populations and that regulate fate determination. Understanding the mechanisms by which the microenvironment regulates stem cell function is challenging because of the complexity of the stem cell niches. However, advances in single-cell technologies now allow expression profiling of the single cells that constitute the different microenvironments. The remaining challenge is to functionally show how the factors produced by the different microenvironments dictate the identity and behaviour of a specific stem cell population.

Intestinal stem cells

The intestinal lining is also highly regenerative and has long been thought to be maintained by stem-like cells6. The lining comprises a single layer of columnar epithelium that is renewed every 3–5 days86. This rapid replacement is supported by progenitor cells that are organized into proliferative units termed crypts of Lieberkühn, which are pockets of cells that are embedded in the wall of the intestine (FIG. 3). Intestinal stem cells (ISCs) located near the bases of these crypts continuously proliferate to support the constant turnover of differentiated cells from the surface.

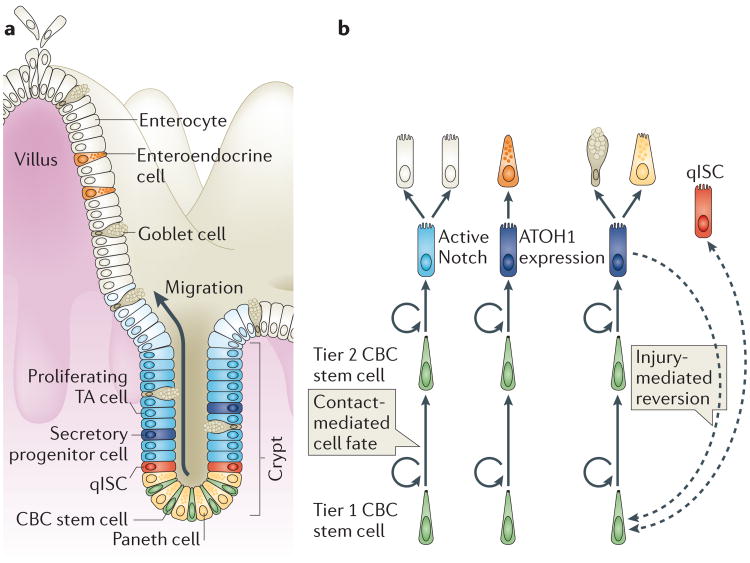

Figure 3. Overview of the intestinal stem cell system.

a | Intestinal progenitor cells are organized in crypts of Lieberkühn. Intestinal stem cells (ISCs) reside near the crypt base and produce daughter cells (transient-amplifying (TA) cells), which proliferate in the mid-crypt and terminally differentiate near the crypt opening to produce the diverse range of intestinal epithelial cell types. Crypt base columnar (CBC) stem cells are interdigitated with Paneth cells at the crypt base. The differentiated cells that line the villus include absorptive enterocytes, goblet cells and enteroendocrine cells. Quiescent ISCs (qISCs; also known as +4 stem cells) are thought to reside just above the zone that contains Paneth and CBC cells. b | CBC cells compete for niche support and space at the base of the crypt, which confers a competitive advantage on the lower (tier 1) CBC cells. Tier 2 CBC cells differentiate as they leave the niche, using contact-dependent Notch signalling to determine their cell fate. Contact with ligand-expressing secretory cells (goblet, enteroendocrine or Paneth cells) activates Notch and directs cells into the absorptive lineage, which gives rise to enterocytes. Contact that is limited to enterocytes or their progenitors results in expression of the transcription factor atonal homologue 1 (ATOH1) and in secretory lineage commitment. Secretory progenitor cells subsequently differentiate into goblet, Paneth or enteroendocrine cells. Extreme injury that causes depletion of the CBC cell pool can induce reversion of committed progenitor cells to a stem cell state (indicated by the dashed arrow). qISCs are thought to give rise to CBC cells following injury. It remains unclear whether a dedicated pool of qISCs exists or whether these cells are transient progenitor cells under homeostatic conditions.

Two claims for intestinal stem cell identity

Historically, two types of ISC were identified. The first, known as crypt base columnar (CBC) cells, was defined using cytological lineage tracing6. The second, termed +4 cells, was defined on the basis of DNA label retention, proliferation and radiation injury response87,88. More recently, CBC and +4 cells have been defined using molecular markers and transgenic lineage-tracing techniques. CBC cells are the proliferative engines that drive cellular production in the crypts: they divide daily, with frequent turnover89. +4 cells have been redefined as reserve or quiescent ISCs (qISCs): they divide infrequently under homeostatic conditions but can be induced to produce new CBC cells in response to injury or other stimuli89.

Proliferation of CBC cells is highly dependent on canonical WNT–β-catenin signalling. Analysis of β-catenin target genes led to the identification of the first molecular marker that was found to be specific to CBC cells, LGR5 (REF. 90), and hence to the discovery of additional CBC cell markers. These markers include achaete-scute homologue 2 (ASCL2), olfactomedin 4 (OLFM4), SPARC-related modular calcium-binding protein 2 (SMOC2) and tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 19 (TNFRSF19)91–94. qISCs were identified by their localization just above the Paneth cell zone at the base of the crypt and by their ability to regenerate the entire crypt in response to injury (typically radiation)95. qISCs were marked by Polycomb complex protein BMI1, doublecortin-like kinase 1 (DCLK1), HOP homeobox (HOPX), LRIG1 and telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT)96–101.

Lineage-tracing experiments suggest that CBC cells and qISCs interconvert; in response to radiation injury or genetic ablation of Lgr5+ CBC cells, qISCs are thought to enter the cell cycle and produce new CBC cells (FIG. 3b), which are indispensable for recovery from radiation injury102–104. Conversely, CBC cells can give rise to qISCs through unknown mechanisms98. However, the existence of a dedicated qISC pool is cur‑ rently the subject of active debate and investigation, as discussed below.

Interestingly, some data suggest that intercellular signalling pathways can differentially regulate CBC cells and qISCs. In contrast to CBC cells, Bmi1+ qISCs were shown to be resistant to β-catenin-driven proliferative signals103. In addition to WNT–β-catenin signalling, other signalling pathways that may differentially contribute to ISC activity include Notch and bone morpho genetic protein (BMP). BMPs counteract mitogenic signals in the crypt, probably by antagonizing canonical WNT signalling105. Markers of BMP activity were found in label-retaining cells but have not been further evaluated in recently identified ISC populations; thus, it remains unclear whether BMP signalling controls CBC cell or qISC activity105. Notch signalling is essential for both promoting self‑renewal and determining the cell fate of differentiating progenitor cells (reviewed in REF. 106). Activation of Notch signalling promotes the absorptive enterocyte fate, whereas cells that do not activate the Notch pathway express atonal homologue 1 (Atoh1) and commit to the secretory cell fate. Emerging data suggest that secretory progenitors may be able to contribute to the stem cell pool in response to injury105,106. In this way, Notch activity could regulate the composition of both the active (CBC cell) and reserve (qISC) pools.

Reverse or reserve — how do crypts regenerate?

Two recent landmark studies suggested that non-stem cells in the crypts have remarkable developmental plasticity when subjected to stress107,108. In one study, cells with high Delta-like 1 (Dll1) expression were shown to be secretory cell precursors, which were not part of the stem cell pool under homeostatic conditions but contributed to the stem cell pool during crypt regeneration following radiation injury. In another study, crypt cells retaining YFP-labelled histone H2B were shown to be secretory progenitor cells. The progeny of these label-retaining cells were marked using a dimerizable Cre enzyme fused to H2B. This approach enabled the authors to show that H2B-labelled cells did not normally contribute to the active stem cell compartment, but after various genotoxic injuries these label-retaining cells contributed to the stem cell pool and to all cell lineages that emerge from those crypts.

These studies suggest that, following severe injury, long-lived secretory progenitor cells can revert to function as stem cells to help to regenerate the intestinal epithelium. Other studies have cast doubt on the validity of qISC markers such as Bmi1 and Dclk1, reporting that they are either broadly expressed throughout the crypt or expressed in a subset of differentiated cells92,109. Furthermore, qISC markers do not identify a homogeneous cell population, and the extent of the overlap of these different cell types has yet to be fully described. Despite the strong evidence that Lgr5− cells can maintain the intestinal epithelium102, the existence of a dedicated qISC pool remains controversial. These recent results raise the question of whether cells previously reported to have stem cell activity are committed progenitors or differentiated cells under homeostatic conditions.

Role of the niche in regulating intestinal stem cell activity

The ISC niche, which consists of supporting epithelial cells, subepithelial stromal cells and the crypt luminal milieu, regulates ISC activity in several ways. Epithelial Paneth cells are interdigitated among the CBC stem cells at the crypt base and provide several important survival and growth factors, including secreted WNT ligands and transmembrane Notch ligands110. Stromal cells provide additional support to ISCs and can compensate for the loss of Paneth cells; this highlights the robustness and adaptability of the ISC niche111,112. Bacterial products such as muramyl dipeptide, a component of the cell wall, can directly stimulate survival of ISCs and resistance to cytotoxic injury113. Moreover, quantitative analyses of clonal expansion, together with recent in situ imaging of cells that express GFP from the Lgr5 promoter, support the idea that the 14–16 CBC cells in each crypt compete with one another for niche support114,115.

An important breakthrough was the development of a three-dimensional epithelial culture system that allowed continuous growth of Lgr5+ CBC cells while they produced the normal constituency of intestinal epithelial cells116. This culture system provides all essential non-epithelial niche signals, including epidermal growth factor, WNT–R-spondin, Noggin and basement membrane components. This experimental platform, known as Sato organoids or enteroids, have been used to identify putative ISCs that are capable of self-renewal and multilineage differentiation, to test the function of putative niche signals and to determine the effects of experimental manipulations on stem cell function98,111,117–119. In addition, organoids have been used to show that Lgr5+ CBC cells are programmed according to their regional identity along the cephalocaudal axis120. These regional identities of ISCs are maintained when the cells are transplanted into an ectopic site in the intestine (for example, transplantation of the small intestine into the colon)121. These data highlight another level of heterogeneity among ISCs.

Together, these data support a model in which CBC cells have equal intrinsic potential for self-renewal. As they divide, their daughter cells compete for niche support: cells that obtain a minimum threshold of niche signals remain stem cells, whereas other daughter cells are forced out of the lower crypt and begin to differentiate. Although all CBC cells may have equivalent potential, CBC cells that reside closer to the crypt base (known as tier 1 CBC cells) may have a self-renewal advantage compared with those that reside farther up the crypt (tier 2 CBC cells), because the daughters of tier 1 CBC cells can better compete for niche space, resulting in two effective levels of CBC self-renewal potential114 (FIG. 3b). A recent study reported that there are 5–7 functionally active stem cells per crypt, which may coincide with tier 1 CBC cells122. As these nascent progenitor cells exit the ISC niche, the composition of their immediate neighbourhood constrains their fate: contact with Notch-ligand-expressing secretory cells specifies these cells as absorptive enterocyte precursors, whereas absence of contact with a secretory neighbour enables those cells to express Atoh1 and commit to the secretory cell fate. This model does not exclude a role for dedicated qISCs, but more studies are needed to clarify the identity of these cells.

An evolving somatic stem cell perspective

It is striking that more than 100 years after the term ‘stem cell’ was coined, we are again debating the interrelationships among different cell types in various tissues. Research in the 1990s focused on identifying a ‘master’ stem cell population for each somatic tissue. As these master stem cells with different markers or behaviour were discovered, there was much heated debate about their identity and differentiation potential. Although many details remain to be resolved, the emerging view of stem cells in each of the three compartments — blood, skin and the intestine — is remarkably similar, leading to two broad conclusions. First, in each tissue, there is more than one population of cells, which express distinct markers, that can behave as stem cells. Thus, there is a new appreciation of stem cell diversity, even within a single stem cell compartment. Second, it seems that each of these stem cell types is more adaptable than had previously been thought: they have a ‘default’ role under normal conditions, but following perturbation, such as stimulation by injury, they can fulfil distinct functions when required.

A key remaining question is whether there is one ‘über’ stem cell in each of these tissues. In the intestine, the cell at the top of the hierarchy that produces all of the lineages during normal homeostasis is an Lgr5+ CBC cell. There is little information about normal homeostasis in the bone marrow, but transplantation experiments suggest that some cells have greater differentiation potential and longevity than others, and these cells may be the ‘über’ stem cells22. In the skin, multiple stem cell populations contribute to distinct compartments of the epidermis during normal homeostasis, indicating that it may lack a master stem cell.

Why are these definitions and cellular relationships important? As we move forward in our attempts to use stem cells for regenerative medicine, it may be very important to be able to distinguish the different regenerative requirements in different circumstances and to identify the best progenitor for a given purpose. The current approach to stem cell transplantation therapy is to provide highly purified stem cells of a specific type. With this new perspective, we can envision scenarios in which multiple types of progenitor are transplanted to support tissue regeneration with the longest duration and with the optimal array of cell types being produced.

Acknowledgments

Research in the Goodell laboratory is supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) (grants DK092883 and CA183252), the Edward P. Evans Foundation, and the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation. Research in the Nguyen laboratory is supported by R01AR059122. Work in the Shroyer laboratory is supported by the US NIH grants DK092456, DK092306, CA1428260 and DK103117.

Glossary

- Quiescence

The state of being inactive. This usually implies limited mitotic activity and is sometimes referred to as dormancy

- Niches

The local environments in which stem cells reside. Niches are thought to regulate stem cell activity through various types of interaction

- CrePR

A Cre recombinase fused with a truncated progesterone receptor that translocates into the nucleus when the receptor binds to the progesterone antagonist RU486

- CreER

A Cre recombinase fused with an oestrogen receptor that translocates into the nucleus when the receptor binds to the oestrogen antagonist tamoxifen. When it translocates to the nucleus, the Cre recombinase is activated and removes the sequences preceding the reporter gene, allowing expression of the reporter

- Quiescent label-retaining cells

Cells that are labelled with a pulse of 5-bromo-2-deoxyuridin e (BrdU) and that retain the BrdU label when followed for a certain amount of time

Footnotes

Competing interests statement: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Pappenheim A. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat Physiol Klin Med. Vol. 145. in German: 1896. Ueber Entwickelung und Ausbildung der Erythroblasten; pp. 587–643. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramalho-Santos M, Willenbring H. On the origin of the term “stem cell”. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:35–38. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker AJ, McCulloch EA, Till JE. Cytological demonstration of the clonal nature of spleen colonies derived from transplanted mouse marrow cells. Nature. 1963;197:452–454. doi: 10.1038/197452a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemischka IR, Raulet DH, Mulligan RC. Developmental potential and dynamic behavior of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 1986;45:917–927. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90566-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keller G, Snodgrass R. Life span of multipotential hematopoietic stem cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1407–1418. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng H, Leblond CP. Origin, differentiation and renewal of the four main epithelial cell types in the mouse small intestine V. Unitarian theory of the origin of the four epithelial cell types. Am J Anat. 1974;141:537–561. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001410407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stange DE, et al. Differentiated Troy+ chief cells act as reserve stem cells to generate all lineages of the stomach epithelium. Cell. 2013;155:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Keymeulen A, et al. Distinct stem cells contribute to mammary gland development and maintenance. Nature. 2011;479:189–193. doi: 10.1038/nature10573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ousset M, et al. Multipotent and unipotent progenitors contribute to prostate postnatal development. Nature Cell Biol. 2012;14:1131–1138. doi: 10.1038/ncb2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H, Nakauchi H. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Müller-Sieburg CE, Cho RH, Thoman M, Adkins B, Sieburg HB. Deterministic regulation of hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Blood. 2002;100:1302–1309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muller-Sieburg CE, Cho RH, Karlsson L, Huang JF, Sieburg HB. Myeloid-biased hematopoietic stem cells have extensive self-renewal capacity but generate diminished lymphoid progeny with impaired IL-7 responsiveness. Blood. 2004;103:4111–4118. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dykstra B, et al. Long-term propagation of distinct hematopoietic differentiation programs in vivo. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:218–229. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.05.015. This landmark study used single-cell transplantation to definitively establish various types of HSC with distinct differentiation preferences. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benz C, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell subtypes expand differentially during development and display distinct lymphopoietic programs. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:273–283. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cavazzana-Calvo M, et al. Is normal hematopoiesis maintained solely by long-term multipotent stem cells? Blood. 2011;117:4420–4424. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-255679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Challen GA, Boles NC, Chambers SM, Goodell MA. Distinct hematopoietic stem cell subtypes are differentially regulated by TGF-ß1. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:265–278. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.02.002. This study was the first to prospectively isolate HSC subtypes and show their differential regulation by a growth factor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morita Y, Ema H, Nakauchi H. Heterogeneity and hierarchy within the most primitive hematopoietic stem cell compartment. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1173–1182. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beerman I, et al. Functionally distinct hematopoietic stem cells modulate hematopoietic lineage potential during aging by a mechanism of clonal expansion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:5465–5470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000834107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent DG, et al. Prospective isolation and molecular characterization of hematopoietic stem cells with durable self-renewal potential. Blood. 2009;113:6342–6350. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benveniste P, et al. Intermediate-term hematopoietic stem cells with extended but time-limited reconstitution potential. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gekas C, Graf T. CD41 expression marks myeloid-biased adult hematopoietic stem cells and increases with age. Blood. 2013;121:4463–4472. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-457929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanjuan-Pla A, et al. Platelet-biased stem cells reside at the apex of the haematopoietic stem-cell hierarchy. Nature. 2013;502:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mallaney C, Kothari A, Martens A, Challen GA. Clonal-level responses of functionally distinct hematopoietic stem cells to trophic factors. Exp Hematol. 2014;42:317–327.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, et al. A differentiation checkpoint limits hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal in response to DNA damage. Cell. 2012;148:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ema H, Morita Y, Suda T. Heterogeneity and hierarchy of hematopoietic stem cells. Exp Hematol. 2014;42:74–82.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramos CA, et al. Evidence for diversity in transcriptional profiles of single hematopoietic stem cells. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moignard V, et al. Characterization of transcriptional networks in blood stem and progenitor cells using high-throughput single-cell gene expression analysis. Nature Cell Biol. 2013;15:363–372. doi: 10.1038/ncb2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo G, et al. Mapping cellular hierarchy by single-cell analysis of the cell surface repertoire. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:492–505. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cabezas-Wallscheid N, et al. Identification of regulatory networks in HSCs and their immediate progeny via integrated proteome, transcriptome, and DNA methylome analysis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:507–522. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun D, et al. Epigenomic profiling of young and aged HSCs reveals concerted changes during aging that reinforce self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:673–688. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beerman I, et al. Proliferation-dependent alterations of the DNA methylation landscape underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Challen GA, et al. Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b have overlapping and distinct functions in hematopoietic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:350–364. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ding L, Saunders TL, Enikolopov G, Morrison SJ. Endothelial and perivascular cells maintain haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2012;481:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nature10783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kunisaki Y, et al. Arteriolar niches maintain haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. 2013;502:637–643. doi: 10.1038/nature12612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamazaki S, et al. Nonmyelinating Schwann cells maintain hematopoietic stem cell hibernation in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2011;147:1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bruns I, et al. Megakaryocytes regulate hematopoietic stem cell quiescence through CXCL4 secretion. Nature Med. 2014;20:1315–1320. doi: 10.1038/nm.3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scadden DT. Nice neighborhood: emerging concepts of the stem cell niche. Cell. 2014;157:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun J, et al. Clonal dynamics of native hematopoiesis. Nature. 2014;514:322–327. doi: 10.1038/nature13824. This work uses transposon tagging to track haematopoietic differentiation in an unperturbed system in the absence of injury for the first time, showing that very long-lived progenitors can sustain a specific lineage over time. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamamoto R, et al. Clonal analysis unveils self-renewing lineage-restricted progenitors generated directly from hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 2013;154:1112–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adolfsson J, et al. Identification of Flt3+ lympho-myeloid stem cells lacking erythro-megakaryocytic potential a revised road map for adult blood lineage commitment. Cell. 2005;121:295–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blanpain C, Fuchs E. Epidermal stem cells of the skin. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:339–373. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Müller-Rover S, et al. A comprehensive guide for the accurate classification of murine hair follicles in distinct hair cycle stages. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:3–15. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rompolas P, et al. Live imaging of stem cell and progeny behaviour in physiological hair-follicle regeneration. Nature. 2012;487:496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature11218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chi W, Wu E, Morgan BA. Dermal papilla cell number specifies hair size, shape and cycling and its reduction causes follicular decline. Development. 2013;140:1676–1683. doi: 10.1242/dev.090662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi K, Rochat A, Barrandon Y. Segregation of keratinocyte colony-forming cells in the bulge of the rat vibrissa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7391–7395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morris RJ, Potten CS. Slowly cycling (label-retaining) epidermal cells behave like clonogenic stem cells in vitro. Cell Prolif. 1994;27:279–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1994.tb01425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cotsarelis G, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Label-retaining cells reside in the bulge area of pilosebaceous unit: implications for follicular stem cells, hair cycle, and skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 1990;61:1329–1337. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90696-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taylor G, Lehrer MS, Jensen PJ, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Involvement of follicular stem cells in forming not only the follicle but also the epidermis. Cell. 2000;102:451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tumbar T, et al. Defining the epithelial stem cell niche in skin. Science. 2004;303:359–363. doi: 10.1126/science.1092436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trempus CS, et al. Enrichment for living murine keratinocytes from the hair follicle bulge with the cell surface marker CD34. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:501–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Horsley V, Aliprantis AO, Polak L, Glimcher LH, Fuchs E. NFATc1 balances quiescence and proliferation of skin stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu Y, Lyle S, Yang Z, Cotsarelis G. Keratin 15 promoter targets putative epithelial stem cells in the hair follicle bulge. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:963–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Youssef KK, et al. Identification of the cell lineage at the origin of basal cell carcinoma. Nature Cell Biol. 2010;12:299–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DasGupta R, Fuchs E. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999;126:4557–4568. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.20.4557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nguyen H, et al. Tcf3 and Tcf4 are essential for long-term homeostasis of skin epithelia. Nature Genet. 2009;41:1068–1075. doi: 10.1038/ng.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rhee H, Polak L, Fuchs E. Lhx2 maintains stem cell character in hair follicles. Science. 2006;312:1946–1949. doi: 10.1126/science.1128004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nowak JA, Polak L, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Hair follicle stem cells are specified and function in early skin morphogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jaks V, et al. Lgr5 marks cycling, yet long-lived, hair follicle stem cells. Nature Genet. 2008;40:1291–1299. doi: 10.1038/ng.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blanpain C, Lowry WE, Geoghegan A, Polak L, Fuchs E. Self-renewal, multipotency, and the existence of two cell populations within an epithelial stem cell niche. Cell. 2004;118:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morris RJ, et al. Capturing and profiling adult hair follicle stem cells. Nature Biotech. 2004;22:411–417. doi: 10.1038/nbt950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Claudinot S, Nicolas M, Oshima H, Rochat A, Barrandon Y. Long-term renewal of hair follicles from clonogenic multipotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14677–14682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507250102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Snippert HJ, et al. Lgr6 marks stem cells in the hair follicle that generate all cell lineages of the skin. Science. 2010;327:1385–1389. doi: 10.1126/science.1184733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jensen UB, et al. A distinct population of clonogenic and multipotent murine follicular keratinocytes residing in the upper isthmus. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:609–617. doi: 10.1242/jcs.025502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nijhof JG, et al. The cell-surface marker MTS24 identifies a novel population of follicular keratinocytes with characteristics of progenitor cells. Development. 2006;133:3027–3037. doi: 10.1242/dev.02443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jensen KB, et al. Lrig1 expression defines a distinct multipotent stem cell population in mammalian epidermis. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:427–439. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghazizadeh S, Taichman LB. Multiple classes of stem cells in cutaneous epithelium: a lineage analysis of adult mouse skin. EMBO J. 2001;20:1215–1222. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.6.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Levy V, Lindon C, Harfe BD, Morgan BA. Distinct stem cell populations regenerate the follicle and interfollicular epidermis. Dev Cell. 2005;9:855–861. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ito M, et al. Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis. Nature Med. 2005;11:1351–1354. doi: 10.1038/nm1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Clayton E, et al. A single type of progenitor cell maintains normal epidermis. Nature. 2007;446:185–189. doi: 10.1038/nature05574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mascre G, et al. Distinct contribution of stem and progenitor cells to epidermal maintenance. Nature. 2012;489:257–262. doi: 10.1038/nature11393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Page ME, Lombard P, Ng F, Göttgens B, Jensen KB. The epidermis comprises autonomous compartments maintained by distinct stem cell populations. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:471–482. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.07.010. Using lineage tracing, this paper shows that discrete pools of stem cells contribute to distinct compartments of the skin epithelium. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brownell I, Guevara E, Bai CB, Loomis CA, Joyner AL. Nerve-derived sonic hedgehog defines a niche for hair follicle stem cells capable of becoming epidermal stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:552–565. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Howard JM, Nuguid JM, Ngole D, Nguyen H. Tcf3 expression marks both stem and progenitor cells in multiple epithelia. Development. 2014;141:3143–3152. doi: 10.1242/dev.106989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Horsley V, et al. Blimp1 defines a progenitor population that governs cellular input to the sebaceous gland. Cell. 2006;126:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kretzschmar K, et al. BLIMP1 is required for postnatal epidermal homeostasis but does not define a sebaceous gland progenitor under steady-state conditions. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:620–633. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liao XH, Nguyen H. Epidermal expression of Lgr6 is dependent on nerve endings and Schwann cells. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:195–198. doi: 10.1111/exd.12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hsu YC, Pasolli HA, Fuchs E. Dynamics between stem cells, niche, and progeny in the hair follicle. Cell. 2011;144:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rompolas P, Mesa KR, Greco V. Spatial organization within a niche as a determinant of stem-cell fate. Nature. 2013;502:513–518. doi: 10.1038/nature12602. Using laser ablation and striking live imaging, this paper shows that the niche determines the fate of stem cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Greco V, et al. A two-step mechanism for stem cell activation during hair regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;4:155–169. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Levy V, Lindon C, Zheng Y, Harfe BD, Morgan BA. Epidermal stem cells arise from the hair follicle after wounding. FASEB J. 2007;21:1358–1366. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6926com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Festa E, et al. Adipocyte lineage cells contribute to the skin stem cell niche to drive hair cycling. Cell. 2011;146:761–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fujiwara H, et al. The basement membrane of hair follicle stem cells is a muscle cell niche. Cell. 2011;144:577–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nishimura EK, et al. Dominant role of the niche in melanocyte stem-cell fate determination. Nature. 2002;416:854–860. doi: 10.1038/416854a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chang CY, et al. NFIB is a governor of epithelial–melanocyte stem cell behaviour in a shared niche. Nature. 2013;495:98–102. doi: 10.1038/nature11847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mezoff E, Shroyer N. In: Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 5th. Hyams JS, Wylie R, editors. Elsevier; 2014. pp. 324–336. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Potten CS, Hume WJ, Reid P, Cairns J. The segregation of DNA in epithelial stem cells. Cell. 1978;15:899–906. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Potten CS, Owen G, Booth D. Intestinal stem cells protect their genome by selective segregation of template DNA strands. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2381–2388. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.11.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gracz AD, Magness ST. Defining hierarchies of stemness in the intestine: evidence from biomarkers and regulatory pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G260–G273. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00066.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Barker N, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.van der Flier LG, et al. Transcription factor achaete scute-like 2 controls intestinal stem cell fate. Cell. 2009;136:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Munoz J, et al. The Lgr5 intestinal stem cell signature: robust expression of proposed quiescent ‘+4’ cell markers. EMBO J. 2012;31:3079–3091. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fafilek B, et al. Troy, a tumor necrosis factor receptor family member, interacts with Lgr5 to inhibit Wnt signaling in intestinal stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:381–391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schuijers J, van der Flier LG, van Es J, Clevers H. Robust Cre-mediated recombination in small intestinal stem cells utilizing the Olfm4 locus. Stem Cell Rep. 2014;3:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.1180794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sangiorgi E, Capecchi MR. Bmi1 is expressed in vivo in intestinal stem cells. Nature Genet. 2008;40:915–920. doi: 10.1038/ng.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Westphalen CB, et al. Long-lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer-initiating cells. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1283–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI73434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Takeda N, et al. Interconversion between intestinal stem cell populations in distinct niches. Science. 2011;334:1420–1424. doi: 10.1126/science.1213214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Powell AE, et al. The pan-ErbB negative regulator Lrig1 is an intestinal stem cell marker that functions as a tumor suppressor. Cell. 2012;149:146–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wong VW, et al. Lrig1 controls intestinal stem-cell homeostasis by negative regulation of ErbB signalling. Nature Cell Biol. 2012;14:401–408. doi: 10.1038/ncb2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Montgomery RK, et al. Mouse telomerase reverse transcriptase (mTert) expression marks slowly cycling intestinal stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:179–184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013004108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Metcalfe C, Kljavin NM, Ybarra R, de Sauvage FJ. Lgr5+ stem cells are indispensable for radiation-induced intestinal regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Yan KS, et al. The intestinal stem cell markers Bmi1 and Lgr5 identify two functionally distinct populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:466–471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118857109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tian H, et al. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature. 2011;478:255–259. doi: 10.1038/nature10408. These authors show that Lgr5+ ISCs are dispensable for intestinal homeostasis and that loss of Lgr5+ cells stimulates expansion of Bmi1+ ‘reserve’ stem cells, which repopulate the crypt. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.He XC, et al. BMP signaling inhibits intestinal stem cell self-renewal through suppression of Wnt–ß-catenin signaling. Nature Genet. 2004;36:1117–1121. doi: 10.1038/ng1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Noah TK, Shroyer NF. Notch in the intestine: regulation of homeostasis and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:263–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Buczacki SJ, et al. Intestinal label-retaining cells are secretory precursors expressing Lgr5. Nature. 2013;495:65–69. doi: 10.1038/nature11965. These authors show that histone H2B label-retaining cells in the intestine are secretory progenitor cells that can revert to become stem cells following genotoxic injury. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.van Es JH, et al. Dll1+ secretory progenitor cells revert to stem cells upon crypt damage. Nature Cell Biol. 2012;14:1099–1104. doi: 10.1038/ncb2581. This work shows that Dll1+ secretory progenitor cells can become activated by injury to repopulate the injured crypt. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gerbe F, et al. Distinct ATOH1 and Neurog3 requirements define tuft cells as a new secretory cell type in the intestinal epithelium. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:767–780. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sato T, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2011;469:415–418. doi: 10.1038/nature09637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Durand A, et al. Functional intestinal stem cells after Paneth cell ablation induced by the loss of transcription factor Math1 (Atoh1) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8965–8970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201652109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kabiri Z, et al. Stroma provides an intestinal stem cell niche in the absence of epithelial Wnts. Development. 2014;141:2206–2215. doi: 10.1242/dev.104976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Nigro G, Rossi R, Commere PH, Jay P, Sansonetti PJ. The cytosolic bacterial peptidoglycan sensor Nod2 affords stem cell protection and links microbes to gut epithelial regeneration. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ritsma L, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis revealed at single-stem-cell level by in vivo live imaging. Nature. 2014;507:362–365. doi: 10.1038/nature12972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Snippert HJ, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sato T, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt–villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Moore SR, et al. Robust circadian rhythms in organoid cultures from PERIOD2∷LUCIFERASE mouse small intestine. Dis Model Mech. 2014;7:1123–1130. doi: 10.1242/dmm.014399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Melendez J, et al. Cdc42 coordinates proliferation, polarity, migration, and differentiation of small intestinal epithelial cells in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:808–819. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Van Landeghem L, et al. Activation of two distinct Sox9-EGFP-expressing intestinal stem cell populations during crypt regeneration after irradiation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1111–G1132. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00519.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Middendorp S, et al. Adult stem cells in the small intestine are intrinsically programmed with their location-specific function. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1083–1091. doi: 10.1002/stem.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fukuda M, et al. Small intestinal stem cell identity is maintained with functional Paneth cells in heterotopically grafted epithelium onto the colon. Genes Dev. 2014;28:1752–1757. doi: 10.1101/gad.245233.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kozar S, et al. Continuous clonal labeling reveals small numbers of functional stem cells in intestinal crypts and adenomas. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Challen GA, et al. Dnmt3a is essential for hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Nature Genet. 2012;44:23–31. doi: 10.1038/ng.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]